Volume 24/2, December 2022, pp. 159-175 | PDF

Jillian Kohler, Anna Wong, and Lauren Tailor

Abstract

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, international access to COVID-19 vaccines and other health technologies has remained highly asymmetric. This inequity has had a particularly deleterious impact on low- and middle-income countries, engaging concerns about the human rights to health and to the equal enjoyment of the benefits of scientific progress enshrined under articles 12 and 15 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. In response, the relationship between intellectual property rights and public health has reemerged as a subject of global interest. In October 2020, a wholesale waiver of the copyright, patent, industrial design, and undisclosed information sections of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS Agreement) was proposed by India and South Africa as a legal mechanism to increase access to affordable COVID-19 medical products. Here, we identify and evaluate the TRIPS waiver positions of World Trade Organization (WTO) members and other key stakeholders throughout the waiver’s 20-month period of negotiation at the WTO. In doing so, we find that most stakeholders declined to explicitly contextualize the TRIPS waiver within the human right to health and that historical stakeholder divisions on the relationship between intellectual property and access to medicines appear largely unchanged since the early 2000s HIV/AIDS crisis. Given the WTO’s consensus-based decision-making process, this illuminates key challenges faced by policy makers seeking to leverage the international trading system to improve equitable access to health technologies.

Introduction

Article 12 of the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) recognizes every person’s human right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, while article 15 recognizes every person’s human right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress.[1] Taken together, this necessarily includes every person’s right to access lifesaving health technologies, such as vaccines, pharmaceuticals, personal protective equipment, and diagnostics. Yet inequities persist, with as many as two billion people in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) lacking regular access to essential medicines.[2]

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, global access to COVID-19 vaccines has remained highly asymmetric despite efforts by global institutions, such as COVAX, to advance such access.[3] When combined with general product shortages, price gouging, export restrictions on health supplies, vaccine manufacturing know-how constraints, and “my nation first” procurement approaches by high-income countries, equitable access to COVID-19 diagnostics and health technologies has been severely undermined.[4] This inequity in access to medicines and health technologies has had a particularly deleterious impact on vulnerable groups throughout the pandemic, notably in LMICs.[5] Two years since the start of the pandemic, several high-income countries have achieved full vaccination coverage in 70%–99% of their populations, while only 15.8% of people in low-income countries have received at least a single dose.[6]

Amid this unequal access to essential medicines and health technologies, the relationship between intellectual property rights and public health has reemerged as a subject of global concern. Pursuant to the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement), all World Trade Organization (WTO) members have an obligation to respect patents issued within their domestic intellectual property (IP) systems irrespective of a patented invention’s initial country of origin.[7] This includes all patents that protect technology essential to the manufacture of COVID-19 vaccines.

Patents are a type of intellectual property right that provides inventors with the temporary right to exclude others from making, selling, or importing their patented technology.[8] As such, patents serve to limit supply and raise prices when manufacturers exercise their monopoly power to under-produce needed pharmaceuticals or charge prices that are out of reach for the majority of populations.[9] These issues are not new and have been raised in discussions surrounding the supply of pharmaceuticals for major diseases, including HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C.[10] Given that nearly all COVID-19 vaccines approved for use are protected by at least one active or pending patent, similar concerns have been raised in the production of COVID-19 vaccines and the associated consequences that this has on health equity.[11]

In October 2020, a wholesale waiver of the copyright, patent, industrial design, and undisclosed information sections of the TRIPS Agreement was proposed by India and South Africa at the WTO on the basis that such a measure would be necessary to ensure that intellectual property rights would not interfere with “timely access to affordable medical products … or to [the] scaling-up of research, development, manufacturing and supply of medical products essential to combat[ing] COVID-19.”[12] In May 2021, the waiver was clarified as intended to apply to all COVID-19-related health products and technologies, including vaccines, therapeutics, medical devices, and personal protective equipment.[13] In March 2022, a compromise between the European Union, India, South Africa, and the United States was proposed to narrow the applicability of the waiver to just COVID-19 vaccines.[14] The compromise also sought to limit the availability of the waiver to only those countries that exported less than 10% of the world’s vaccines in 2021.[15] Government responses to the waiver and its proposed alternatives have been divided, but as of June 2022, WTO members agreed to a modified version of the limited March 2022 waiver applicable for five years to COVID-19 vaccines.[16] Further conditions notably include a restriction on the waiver’s availability to only developing country WTO members, country obligations to prevent the re-exportation of products made under the waiver, and a six-month extension of discussions on expanding the waiver’s scope to COVID-19 therapeutics and diagnostics.[17]

To better understand the justifications and implications of the TRIPS waiver negotiations and June 2022 compromise, we identify and evaluate the positions of WTO members and other key stakeholders with respect to the waiver and its relationship to health as a human right. In doing so, we find that historical stakeholder identities and positions with respect to IP and access to medicines have remained largely unchanged. Given the consensus-based decision-making at the WTO, this suggests that political and structural barriers continue to play a large role in limiting policy makers’ ability to leverage the international trading system to improve equitable access to health technologies.

Methodology

A descriptive, qualitative study drawing on critical policy studies methodologies, focusing on how interests, values, and normative assumptions shape and inform policy formation and implementation, was conducted to analyze the public statements of WTO members, pharmaceutical stakeholders, and civil society organizations with respect to the TRIPS waiver.[18] In particular, a combined inductive and deductive thematic analysis was employed to identify reoccurring TRIPS waiver position rationales expressed across each stakeholder and position class and to specifically search for rationales grounded in human rights-related appeals.[19] Data were independently abstracted by AW and LT, with JK resolving any discrepancies through an additional round of review.

Document identification

Official WTO member positions on the TRIPS waiver were sourced from WTO General Council and TRIPS Council meeting minutes from October 2020 to June 2022, as well as all official WTO member submissions related to the COVID-19 TRIPS waiver.[20] Based on these documents, a final list of all WTO members and their positions with respect to the TRIPS waiver was compiled. This list was then verified for consistency with an internal Médecins Sans Frontières policy tracker, which the organization used to construct its public infographic on TRIPS waiver country positions and shared with the authors upon request.[21]

Thirty statements from over 350 civil society organizations included for analysis were extracted from submissions to the WTO’s official COVID-19 public consultation docket and the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives TRIPS COVID-19 waiver civil society letter repository (see Appendix 1, available upon request).[22] Sixty-six pharmaceutical companies were included for analysis and were selected based on size (top 20 multinational companies by 2020 revenue) and involvement in COVID-19 product development (COVAX suppliers), with all TRIPS waiver-related press releases recorded.[23] Official statements made by pharmaceutical trade organizations Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, Biotechnology Innovation Organization, International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations, and European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations were also queried (see Appendix 2, available upon request).

Document analysis

Documents were analyzed to identify the following elements: (1) country/organization identity, (2) country/organization position with respect to the TRIPS waiver (support, neutral or undetermined, opposed), and (3) country/organization rationale for their TRIPS waiver position. Stakeholder positions with respect to the TRIPS waiver were determined based on their explicit endorsement or rejection of any iteration of the waiver before the March 2022 compromise, or their qualitative expressions of support for or objection to any iteration of the waiver before the March 2022 compromise. Stakeholders whose positions were expressed in multiple documents were deemed to have adopted the position expressed in the document reporting their most recent public statement. Stakeholders who released statements that did not clearly express support or objection to the TRIPS waiver were classified as neutral or undetermined and, due to the limited public statements available in this category, were not analyzed further for their position rationales. Explicit references to “human rights” or rights-based assertions to health found in these documents were separately extracted for analysis.

Results

Overall, the majority of WTO members and surveyed civil society organizations expressed support for a COVID-19 TRIPS waiver—either in its original October 2020 form or limited March 2022 form. By contrast, nearly all pharmaceutical industry stakeholders who issued public statements voiced opposition to all iterations of the TRIPS waiver. While these positions align strongly with the historical approaches of these stakeholders, a survey of the specific rationales presented by each provides greater insight into the primary sources of axiomatic contention during the COVID-19 TRIPS waiver discussions. The following section provides a breakdown of each of these stakeholder groups’ positions with respect to the waiver, as well as the dominant rationales offered for these positions.

WTO members

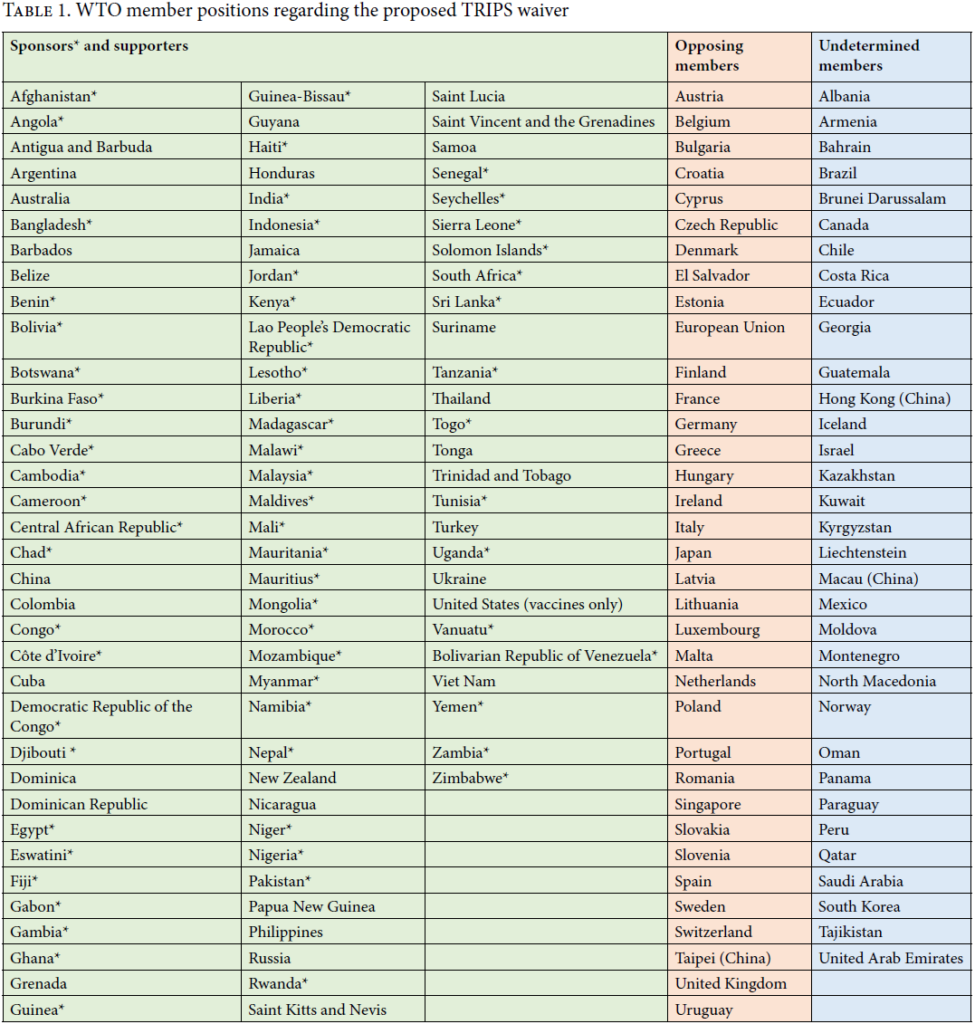

Until June 2022, approximately 60% of WTO members expressed support for a TRIPS waiver, either as outright sponsors or through favorable endorsement of the waiver. Approximately 21% of members expressed opposition to the TRIPS waiver (with 28 of the 35 opposing members belonging to the European Union or the European Union delegation itself). The remaining 19% of member positions were undetermined, either because they did not publicly comment on the TRIPS waiver or because their comments refrained from expressing a definitive position with respect to the waiver. The breakdown of WTO member positions and their position rationales is outlined in Table 1.

WTO member rationales for supporting a TRIPS waiver. WTO members in support of the TRIPS waiver advanced four main arguments: (1) the TRIPS waiver is required to address IP-based barriers to access that the existing voluntary and compulsory licensing system is ill-equipped to manage; (2) the TRIPS waiver is important as a tool for promoting further COVID-19 solutions that are consistent with the human right to health; (3) the TRIPS waiver should include vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics, since a waiver just for vaccines would be insufficient to adequately address COVID-19; and (4) the TRIPS waiver is a legitimate trade policy tool under the existing WTO rules. Below, each rationale is discussed in further detail.

- IP is a barrier to access that cannot be addressed by voluntary or compulsory licensing

Members in support of the TRIPS waiver all adopted the position that IP is actively serving as a supply barrier by preventing the mass manufacture of needed COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and medical devices. Many further argued that this barrier cannot be adequately addressed through voluntary licensing agreements with manufacturers or by issuing compulsory licenses to expand supply. South Africa emphasized that voluntary licensing agreements suffer from a lack of transparency, impose geographic restrictions that often prohibit export even to developing countries, and typically have only a nominal effect on increasing overall market supply.[24] Many countries also argued that the country-by-country and product-by-product approach to compulsory licensing prescribed under articles 31 and 31bis of the TRIPS Agreement, which enable countries to manufacture and import generic versions of patented products without a patent owner’s consent, undermined the cross-border and widespread use of compulsory licenses required to respond to an international pandemic. India emphasized that ownership disputes among COVID-19 vaccine patent holders would likely compound delays in the articles 31 and 31bis processes, since countries would potentially need to identify and send notice to multiple litigating owners to ensure compliance with TRIPS compulsory licensing procedures.[25] A lack of domestic legal capacity to engage in compulsory licensing was also highlighted by some states as further support that compulsory licensing is inadequate for supplying COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and medical devices at an international scale.[26]

2. A TRIPS waiver is a tool consistent with promoting the human right to health

Several WTO members highlighted the sharp inequities among high-income and low-income countries regarding access to COVID-19 vaccines. For example, Bangladesh underscored the effects of vaccine nationalism and the lack of access faced by least developed countries, highlighting that the richest 16% of the world had “pre-booked” the majority of vaccines until 2025.[27]

In response to claims by opposing members that COVAX, rather than a TRIPS waiver, was the solution to ensuring equity, supporting members emphasized that “the problem with philanthropy [COVAX] is that it cannot buy equality.”[28] In a position summary document submitted by TRIPS waiver sponsors in September 2021, they underscored that the adoption of the TRIPS waiver would act “as an important political, moral, and economic lever towards encouraging solutions aimed at global equitable access to COVID-19 health products and technologies.”[29] The preambular text of the document emphasized that in seeking equitable health outcomes, the TRIPS waiver was consistent with “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health” protected under article 12 of the ICESCR, as well as the “bold commitment” under United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 3 to ending communicable diseases, achieving universal health coverage, and providing access to safe and effective medicines and vaccines for all.[30]

3. A TRIPS waiver for just vaccines is insufficient

Several supporting members emphasized the importance of including all relevant health technologies—rather than just vaccines—within the scope of the waiver. In particular, sponsors urged WTO members to recall that “vaccines are necessary but not sufficient” and that personal protective equipment, diagnostics, ventilators, and therapeutics are all essential to preventing the spread and ensuring the treatment of COVID-19.[31]

4. A TRIPS waiver is an established and accepted option under existing WTO rules

Many supporting members highlighted that under article IX.3 of the WTO Marrakesh Agreement, waivers of obligations imposed under WTO trade agreements can be legitimately employed in exceptional circumstances.[32] In the October 2020 TRIPS Council meeting, this was affirmed by the WTO Secretariat, which stated that the Ministerial Conference “may decide to waive an obligation imposed on a Member by the Marrakesh Agreement or any of the [WTO’s] multilateral trade agreements.”[33] Supporting members have argued that approving a temporary TRIPS waiver to address urgent public health needs during the COVID-19 pandemic should thus be seen as consistent with, rather than an exception to, the rules-based multilateral trading system.[34]

WTO member rationales for opposing a TRIPS waiver. Four primary rationales were advanced by WTO members opposed to the TRIPS waiver: (1) a TRIPS waiver would not be effective in increasing global supplies since patents and the TRIPS Agreement are not a barrier to access; (2) access to needed COVID-19 health technologies can be addressed through nominal modifications to the TRIPS compulsory licensing system; (3) a TRIPS waiver would introduce legal uncertainty to the international system, thus undermining existing licensing partnerships that are essential to expanding access; and, (4) a TRIPS waiver would undermine the growth of the IP-dependent health technology sector, contrary to domestic development interests. Below, each rationale is discussed in further detail.

- Patents and existing TRIPS obligations are not a barrier to access

Nearly all opposing members endorsed a view that the patent and other IP protection obligations mandated under the TRIPS Agreement are not a primary factor responsible for limiting access to needed COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, or medical devices. Instead, members urged that temporary demand shocks, manufacturing capacity constraints, and supply chain delays were “much more likely to have an impact on access than [intellectual property rights].”[35] Several members cited a 2021 interview with the Serum Institute of India’s CEO Adar Poonawalla, who stated that he believed global supply shortages were due to short-term scale-up delays rather than insufficient licensing to generic manufacturers by patent owners.[36]

2. Access to needed COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and medical devices can be addressed through minor modifications to existing compulsory licensing rules

The European Union suggested that any IP-related access challenges arising during COVID-19 could instead be addressed through nominal changes to the TRIPS articles 31 and 31bis compulsory licensing framework. In particular, the European Union argued that delays arising from the system’s existing country-by-country and product-by-product notification requirements could be overcome by implementing an emergency uniform notification requirement.[37] Under this alternate proposal, members would provide the WTO Secretariat with a single compulsory licensing notice outlining all vaccines and recipient countries that they planned on supplying under compulsory license, thus reducing alleged administrative burdens to compulsory licensing faced by members in support of the waiver.

3. A TRIPS waiver would undermine existing voluntary licensing partnerships

Several members emphasized that a TRIPS waiver would do more harm than good by destabilizing the international IP framework, and in doing so, jeopardize existing voluntary licensing partnerships between patent holders and third-party manufacturers. In particular, Switzerland highlighted the importance of a “safe regulatory framework” that is “predictable and accountable,” and argued that the TRIPS waiver risked the efforts of the 300+ international partnerships currently working to build production capacity.[38] The need for legal stability to ensure productive and effective technology transfer between originator and generic manufacturers was also underscored.

4. A TRIPS waiver would undermine the development of domestic health technology industries

Several WTO members cited concerns that a TRIPS waiver would undermine innovation in the pharmaceutical sector, thus harming the development of their local industries. For example, while Chile acknowledged that “[the protection of] IP is not an end in itself,” it nonetheless viewed IP as an important tool for development.[39] Similarly, during early TRIPS waiver discussions, both Russia and El Salvador emphasized that “promoting and incentivizing innovation as a tool for boosting and accelerating development” was “a top national priority.”[40] As a result, El Salvador found it “difficult to reconcile” the waiver with the domestic development objectives that it had set as a country.”[41]

Civil society organizations

Over 350 civil society groups, including access to medicines groups, HIV/AIDS organizations, global health and global justice alliances, and human rights groups, expressed strong support for the TRIPS waiver, with many further arguing that governments should view the waiver as a minimum first step to securing access to needed COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and medical devices. Statements from these groups were often directly addressed to heads of WTO members, with requests that governments view the adoption of the waiver as an urgent matter. Four major rationales were advanced by these organizations: (1) the TRIPS waiver enables countries to overcome IP-based supply barriers that cannot be adequately addressed through voluntary or compulsory licensing; (2) the TRIPS waiver enables countries to uphold their human rights obligations; (3) the TRIPS waiver is a necessary but insufficient step toward achieving equitable access to health technologies during COVID-19; and (4) corporate profit should not be prioritized over equitable access. Below, each rationale is discussed in further detail.

- IP is a barrier to access that cannot be addressed by voluntary or compulsory licensing

Civil society organizations endorsed the view that IP obstructs the production and distribution of affordable COVID-19 health technologies. Many noted that relying solely on voluntary licensing is not a sufficient remedy, as historically it has “failed to leverage global expertise and capacity to scale up manufacturing and deliver equitable access.”[42] Furthermore, the existing compulsory licensing mechanism designed to lawfully circumvent these restrictions was seen to suffer from scaling issues. Many argued that countries are obliged to issue compulsory licenses on a country-by-country and product-by-product basis, and thus that the existing compulsory licensing system is ill-suited for rapid global distribution. It was asserted by many that addressing international access concerns through compulsory licenses “would create a monumental coordination crisis because of the possible need to initiate and win compulsory licensing proceedings in multiple jurisdictions.”[43] Groups highlighted that LMICs have been historically “discouraged from using compulsory licensing for access to medicines due to pressures from their trading partners and pharmaceutical corporations” and that the article 31bis compulsory licensing pathway has been successfully employed only once, to import patented pharmaceuticals to Rwanda.[44] The TRIPS waiver was promoted as a solution to overcoming these IP-related issues at a global scale necessary to addressing an international pandemic.

2. A TRIPS waiver enables states to uphold their international human rights obligations

Many civil society organizations emphasized the role of a TRIPS waiver in ensuring equal access to critical health technologies consistent with the human rights to health, to receiving and imparting information, to education, to participating in cultural life, and to equally benefitting from scientific progress. In a letter signed by 107 groups, governments were urged to recognize the inequalities exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, with an emphasis on the resulting unequal access to vital technological knowledge among countries.[45] These groups emphasized the importance of ensuring that essential COVID-19 research is made available immediately and everywhere, and argued that “removing legal barriers to knowledge is… needed for the massive, urgent scale-up of vaccine production.”[46] Others echoed WHO Director-General Tedros Ghebreyesus’s 2021 statement that “profits and patents must come second to the human right to health” in supporting arguments that COVID-19 vaccines, as the “common property of humanity,” must be made available as a matter of human rights.[47] The role of the TRIPS waiver as a tool for redressing global inequalities in access to COVID-related health technologies was asserted in most statements.

3. The TRIPS waiver is necessary but insufficient for securing equitable access

Several civil society organizations framed the TRIPS waiver as the necessary but insufficient first of a series of measures that governments must take to ensure equitable access to lifesaving COVID-19 health technologies.[48] In addition, these groups advocated for know-how and technology transfer from patent holders to manufacturers in the Global South, increased direct investment into the expansion of manufacturing capacity in the Global South, and equitable dose sharing from the Global North to the Global South.[49] After the release of the amended waiver in June 2022, over 200 civil society organizations expressed dissatisfaction with the draft ministerial decision and the insufficiency of its application solely to COVID-19 vaccines, its exclusion of some of the world’s largest producers of medical tools, and its restriction of “the free movement and rapid distribution of needed medical products.”[50]

4. Moral appeal: corporate profits should not be prioritized over equitable access

Many civil society organizations adopted the moral position that governments should not prioritize the financial needs of the pharmaceutical industry over the immediate health of humans in need. Emphasis was placed on the collective state responsibility for human life, as well as the priority of this responsibility over states’ competing responsibilities to honor corporate monopolies.[51]

Research-based pharmaceutical companies

Approximately 48.5% of pharmaceutical companies expressed opposition to the proposed TRIPS waiver, either by directly authoring statements or endorsing statements authored by industry-wide associations. These included five companies (AstraZeneca, BioNTech, Janssen, Pfizer, and Sanofi) that are currently partnered with COVAX for the purpose of supplying vaccines to LMICs, as well as pharmaceutical manufacturing trade associations Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations, and European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations. Approximately 7.5% of manufacturers (Bharat Biotech, Biological E, CureVac, Gamaleya, and Moderna) released neutral statements about the TRIPS waiver, indicating a willingness to not enforce their own intellectual property rights but refraining from explicitly endorsing the waiver. The remaining 44% did not release statements about the TRIPS waiver.

The primary arguments advanced against the TRIPS waiver were that (1) a TRIPS waiver would not be effective in increasing global supplies since IP is not a barrier to access; (2) a TRIPS waiver would threaten innovation, thus reducing the pharmaceutical industry’s ability to produce lifesaving technologies; (3) a TRIPS waiver would undermine existing partnerships among manufacturers; and (4) a TRIPS waiver would not rapidly rectify vaccination deficits, which is the ultimate goal of the international COVID-19 response. These arguments are presented below.

- IP is not a barrier to access

Almost all pharmaceutical companies refuted the assertion that IP protection has limited access to patented COVID-19 health technologies throughout the pandemic. Instead, focus was placed on trade restrictions, distribution bottlenecks, and raw material scarcity.[52] Manufacturers emphasized the sufficiency of existing manufacturing capacity and supply chains to provide COVID-19 vaccines to the world’s population, stating that “in 2021, more than 40% of these [3 billion] doses are expected to go to middle- and low-income countries. We believe … that in the next 9 to 12 months, there will be more than enough vaccines produced.”[53] Given these assertions, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America and the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations argued that a TRIPS waiver would be not only unnecessary but harmful to existing manufacturer efforts to expand access through voluntary licensing and technology transfer agreements.[54]

2. A TRIPS waiver threatens innovation

Pharmaceutical manufacturers frequently expressed their opposition to the TRIPS waiver on grounds that waiving IP protection would threaten innovation. Premised on the assertion that IP protections enable innovators to earn the returns necessary to finance risky pharmaceutical research and development (R&D), manufacturers asserted that a TRIPS waiver would undermine ongoing efforts to develop health technologies for new COVID-19 variants.[55] Manufacturers also cited the proposed waiver’s broader deleterious effects on scientific innovation at large, with Pfizer’s chairman and CEO releasing a public letter expressing concern that a TRIPS waiver would disincentivize scientific investments to the particular detriment of small, investor-dependent biotech innovators.[56]

3. A TRIPS waiver would undermine existing voluntary licensing partnerships

Throughout the pandemic, manufacturers of patented COVID-19 vaccines have underscored their efforts to ensure expanded access by entering into voluntary licensing agreements with third-party manufacturers. In implementing a waiver that would enable countries to suddenly cease enforcing domestic intellectual property rights, manufacturers argued that WTO members risked placing these ongoing inter-manufacturer supply agreements at risk.[57] Two key rationales were presented to support the assertion that IP enforcement is a vital component to ongoing voluntary licensing agreements. First, manufacturers argued that voluntary licenses enable patent owners to carefully pick partner manufacturers that are best equipped to produce quality products.[58] Without such oversight in place, it was alleged that the safety and efficacy of produced vaccines would be threatened.[59] Second, manufacturers asserted that a TRIPS waiver would exacerbate raw material shortages, thus undermining ongoing partnerships, as “entities with little or no experience in manufacturing vaccines [would be] likely to chase the very raw materials that [current manufacturers] require to scale production.”[60]

4. A TRIPS waiver is not a sufficiently rapid solution for rectifying international vaccination deficits

Several manufacturers acknowledged the importance of equitable access to vaccines but maintained that the proposed TRIPS waiver would be unable to rapidly rectify existing vaccination deficits. Instead, they asserted that focus should be shifted toward enhancing voluntary technology transfer arrangements, increasing health infrastructure funding, and expanding educational programs to combat vaccine hesitancy.[61] For example, a statement by AstraZeneca’s executive vice president of Europe and Canada emphasized that “the TRIPS process is no quick fix and could take many months—far too late for millions of people in underserved communities”—and advocated for a suite of “urgent response” measures, including not-for-profit pricing commitments by manufacturers, expanded regional supply chains, and voluntary technology transfer agreements with domestic manufacturers in the Global South.[62]

Discussion

Stakeholder rationales align with historic divides on the relationship between IP and access to medicines

Among the 131 WTO members that expressed a definite position with respect to the TRIPS waiver, we found that approximately 73% support the waiver (with 65 of 96 supporters endorsing the waiver as co-sponsors). Over 350 civil society groups overwhelmingly aligned with those WTO members in support of the waiver. By contrast, approximately 86% (30 out of 35) pharmaceutical industry stakeholders who issued or endorsed statements regarding the TRIPS waiver uniformly aligned with those WTO members opposed to the waiver.

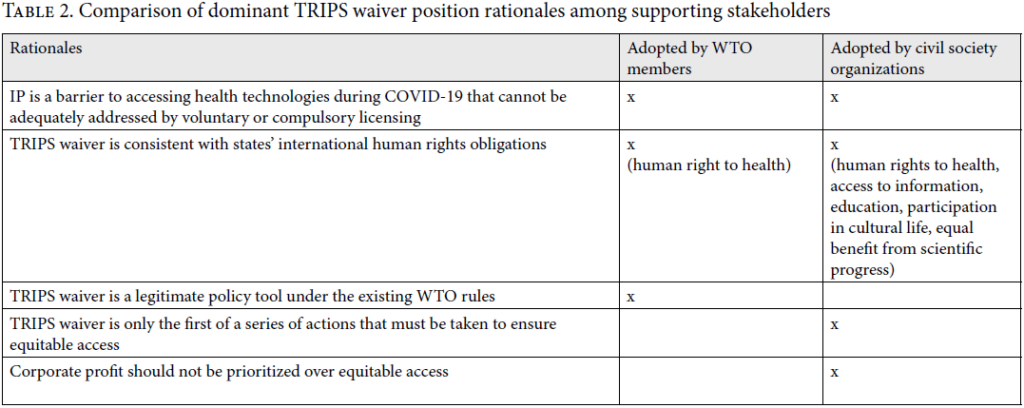

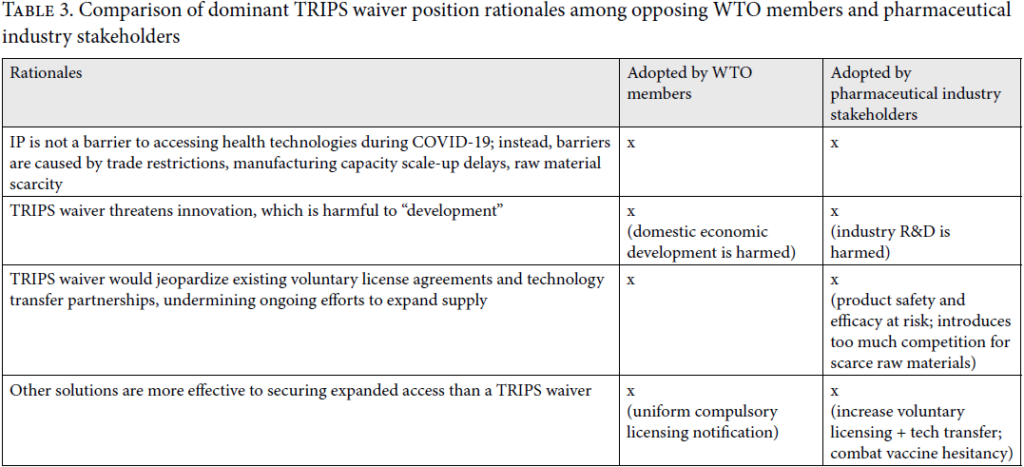

WTO members opposed to the TRIPS waiver shared overlapping arguments with pharmaceutical industry stakeholders more frequently than endorsing WTO members did with civil society organizations (see Tables 2 and 3). The WTO members that were the most vocally opposed to the TRIPS waiver (the United Kingdom, European Union, and Switzerland) and whose arguments aligned most strongly with pharmaceutical industry stakeholders were also those members in which COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers (AstraZeneca, BioNTech/Pfizer, and Moderna) maintain headquarters or major manufacturing facilities. By contrast, the WTO members that most frequently expressed support for the TRIPS waiver in alignment with civil society-backed rationales were those countries with large domestic generic manufacturing capacities (e.g., India) or that had previously considered or engaged in compulsory licensing for pharmaceuticals (e.g., South Africa, Malaysia, and Sri Lanka). This aligns with the view that in the context of the WTO, an institution primarily designed to facilitate the commercial exchange of goods and services between countries, many members’ decisions to support health-related proposals likely remain highly dependent on prevailing domestic economic priorities.

Notably, several dominant rationales offered by WTO members, pharmaceutical stakeholders, and civil society organizations reflect the same arguments raised during the HIV/AIDS crisis in the early 2000s surrounding the use of compulsory licenses to expand access to antiretrovirals.[63] At the time, pro-compulsory licensing advocates frequently appealed to states’ humanitarian obligations and emphasized the importance of protecting human lives over private profits, while pro-IP advocates rooted their position on grounds of recouping R&D costs, promoting innovation, and securing product quality.[64] The continued use of this language in the context of TRIPS waiver discussions—and the upending endorsement of compulsory licensing by TRIPS waiver opponents as a more feasible solution than the waiver—suggests that the relationship between IP and access to medicine remains highly contentious within the trade and health landscape despite the 2001 Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health.[65] Since the WTO operates as a consensus-based decision-making body, this continued division between members presents as a key policy obstacle for states seeking to leverage the international trade system to promote expanded access to health technologies within their domestic health systems.

The TRIPS waiver and human rights

Among all stakeholders, the importance of ensuring equitable access to COVID-19 health technologies has not been refuted. In TRIPS waiver discussions among WTO members, differences in vaccine prices and availability between high-income countries and LMICs were frequently highlighted by members as evidence of ongoing inequalities. For example, South Africa argued that it had been charged US$5.25 per dose for AstraZeneca’s vaccine while European Union members had been charged only US$3.50.[66] Several LMIC members also expressed frustration with the unavailability of vaccines for their own populations due to the bilateral supply deals negotiated in advance between high-income countries and manufacturers.

To varying degrees, all WTO members, civil society organizations, and pharmaceutical industry stakeholders that authored or endorsed statements related to the TRIPS waiver acknowledged the importance of rectifying the asymmetric distribution of COVID-19 vaccines between high-income countries and LMICs. However, only civil society organizations consistently framed this inequality in terms of explicit human rights considerations. Here, inequitable international COVID-19 vaccine deployment was frequently viewed as a violation of the human rights to health and to benefit from scientific progress, enshrined in articles 12 and 15 of the ICESCR. The TRIPS waiver was thus supported as an urgent measure explicitly required to rectify ongoing human rights violations. By contrast, WTO members largely refrained from employing human rights language during TRIPS waiver discussions, with the sole reference to article 12 of the ICESCR found in the preambular text of TRIPS waiver sponsors’ September 2021 position summary document.[67] WTO members opposed to the TRIPS waiver often couched their positions in terms of equitable vaccine access, citing either the independent or combined sufficiency of COVAX and inter-manufacturer voluntary licensing agreements in attaining this goal. Similarly, pharmaceutical manufacturers frequently underscored their post-scaling ability to supply vaccines to LMICs that were previously unable to secure doses at the beginning of the pandemic. Thus, while not always framed in terms of explicit human rights obligations, ensuring equitable international access to COVID-19 vaccines has been recognized as a desirable objective by TRIPS waiver proponents and opponents alike—with the efficacy of the proposed TRIPS waiver in successfully achieving this goal at issue.

Given members’ polarizing positions with respect to the TRIPS waiver and the WTO requirement that resolutions be passed through consensus, it is perhaps unsurprising that TRIPS waiver negotiations have struggled to advance. In an attempt to broker a compromise acceptable to all WTO members, the March 2022 TRIPS waiver solution proposed by the European Union, India, South Africa, and the United States sought to make the TRIPS waiver more palatable to opposing members while still providing members with a more streamlined alternative to the compulsory licensing system in articles 31 and 31bis of the TRIPS Agreement.[68] Public responses to this proposal were largely critical. Civil society organizations decried the compromise as a partial measure incapable of meaningfully increasing access to COVID-19 health technologies and legally unprecedented in its narrow interpretation of the existing article 31 compulsory licensing regime.[69] Conversely, COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers emphasized the compromise’s lack of necessity given recent reports of vaccine overproduction and global demand reductions.[70] Comparable reactions were also elicited from these groups in response to the narrower June 2022 draft decision text. Notably, while civil society groups and pharmaceutical stakeholders alike demonstrated a strong reluctance to endorse compromises that deviated significantly from their original positions, the June 2022 compromise required many WTO members to endorse positions that they initially opposed. While this indicates that the rules-based international trading system remains capable of encouraging consensus-building among its members, the two years of debate preceding this decision suggest that trade-based public health measures are likely ill-suited as first-line responses to urgent and international public health crises.

Conclusion

Access to lifesaving health technologies, such as COVID-19 vaccines, remains starkly inequitable between countries. Reponses by WTO members, civil society organizations, and pharmaceutical industry stakeholders to the proposed TRIPS waiver highlight universal acknowledgment of this unequal health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, where proponents view the TRIPS waiver as a necessary first step toward eliminating IP-driven barriers to access during the pandemic, opponents largely assert that the TRIPS waiver is a political distraction that is both unnecessary and incapable of rapidly expanding the supply of COVID-19 health technologies.

Discourse surrounding the TRIPS waiver suggests that the global community seems to be expressing similar IP and public health arguments as those advanced during the HIV/AIDS crisis. This underscores the continued lack of reliability that countries face when looking to the international trading system as a means to advance public health imperatives and improve access to lifesaving health products. It also suggests the need for deep structural change and how lessons learned are often forgotten.

As WTO members consider the adoption of an expanded TRIPS waiver, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread globally with new emerging variants. Without improved international coordination, transparency, and consideration for the health and human rights of all global citizens, states risk remaining ill-prepared for future pandemics and global emergencies. Governments must therefore continue to collectively strive toward the development of equitable solutions so that meaningful progress can be made to improve global access to essential health products. Without decisive action, countries risk being unprepared for future public health crises and continuing to propagate patterns of health inequity.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the feedback received from Sharifah Sekalala, Katrina Perhudoff, Lisa Forman, and others during the Connaught Global Challenge Research Program’s “Advancing Rights-Based Access to COVID-19 Vaccines as Part of Universal Health Coverage” paper development workshop on May 17, 2022.

Funding

We thank the Connaught Global Challenge Award for funding for this research through the “Advancing Anti-Corruption, Transparency and Accountability Mechanisms to Tackle Corruption in the Pharmaceutical System” and the “Advancing Rights-Based Access to COVID-19 Vaccines as Part of Universal Health Coverage” grants.

Ethics approval

Since this research exclusively employed data obtained from public documents, no ethics approval was required.

Jillian Kohler, PhD, is a professor at the University of Toronto Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, and Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, Toronto, Canada, and founding director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Governance, Accountability and Transparency in the Pharmaceutical Sector.

Anna Wong is a JD candidate at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law, Toronto, Canada, and research associate at the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Governance, Accountability and Transparency in the Pharmaceutical Sector.

Lauren Tailor, MPH, PharmD, is a PhD student at the University of Toronto Dalla Lana School of Public Health, Toronto, Canada, and a research assistant at the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Governance, Accountability and Transparency in the Pharmaceutical Sector.

Please address correspondence to Jillian Kohler. Email: jillian.kohler@utoronto.ca.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2022 Kohler, Wong, and Tailor. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/bync/4.0/), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction.

References

[1] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI) (1966), arts. 12, 15.

[2] World Health Organization, Ten Years in Public Health, 2007–2017 (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017).

[3] L. Paremoer, S. Nandi, H. Serag, and F. Baum, “COVID-19 Pandemic and the Social Determinants of Health,” British Medical Journal 372/129 (2021); G. Yamey, P. Garcia, F. Hassan, et al., “It Is Not Too Late to Achieve Global COVID-19 Vaccine Equity,” British Medical Journal 376 (2022); T. Mousavi, S. Nikfar, and M. Abdollahi, “Achieving Equitable Access to Medicines and Health Services: A COVID-19-Time Recalled Matter,” Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 20/4 (2021); C. Batista, P. Hotez, Y. B. Amor, et al., “The Silent and Dangerous Inequity around Access to COVID-19 Testing: A Call to Action,” EClinicalMedicine 43 (2022); A. De Bengy Puyvallée and K. T. Storeng, “COVAX, Vaccine Donations and the Politics of Global Vaccine Inequity,” Globalization and Health 18/26 (2022).

[4] G. Yamey et al. (see note 3); E. T. Tagoe, N. Sheikh, A. Morton, et al., “COVID-19 Vaccination in Lower-Middle Income Countries: National Stakeholder Views on Challenges, Barriers, and Potential Solutions,” Frontiers in Public Health 9 (2021); S. Owermohle, “Drug Prices Steadily Rise amid Pandemic, Data Shows,” Politico (July 7, 2020), https://www.politico.com/news/2020/07/07/drug-prices-coronavirus-351729; T. Bollyky and C. Bown, “The Tragedy of Vaccine Nationalism: Only Cooperation Can End the Pandemic,” Foreign Affairs 9/5 (2020); W. Zhang, “Export Restrictions on Medical Supply amidst a Pandemic,” Sidley Austin LLP (February 2021), https://www.sidley.com/en/insights/publications/2021/02/export-restrictions-on-medical-supply-amidst-a-pandemic; J. Feinmann, “COVID-19: Global Vaccine Production Is a Mess and Shortages Are Down to More Than Just Hoarding,” British Medical Journal 375 (2021).

[5] D. Devakumar, G. Shannon, S. S. Bhopal and I. Abubakar, “Racism and Discrimination in COVID-19 Responses,” Lancet 395/10231 (2020).

[6] D. J. Hunter, S. S. Abdool Karim, L. R. Baden, et al., “Addressing Vaccine Inequity: COVID-19 Vaccines as a Global Public Good,” New England Journal of Medicine 386/12 (2022); E. Mathieu, H. Ritchie, E. Ortiz-Ospina, et al., “A Global Database of COVID-19 Vaccinations,” Nature Human Behaviour 5 (2021); Our World in Data, “Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations,” https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations; V. Pilkington, S. M. Keestra, and A. Hill, “Global COVID-19 Vaccine Inequity: Failures in the First Year of Distribution and Potential Solutions for the Future,” Frontiers in Public Health 10 (2022).

[7] Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization, Annex 1C, 1896 U.N.T.S. 299 (1994), art 27.

[8] World Intellectual Property Organization, “Frequently Asked Questions: Patents,” https://www.wipo.int/patents/en/faq_patents.html.

[9] N. S. Jecker and C. A. Atuire, “What’s Yours Is Ours: Waiving Intellectual Property Protections for COVID-19 Caccines,” Journal of Medical Ethics 47 (2021).

[10] E. ‘t Hoen, J. Berger, A. Calmy, and S. Moon, “Driving a Decade of Change: HIV/AIDS, Patents and Access to Medicines for All,” Journal of the International AIDS Society 14 (2011); B. R. Edlin, “Access to Treatment for Hepatitis C Virus Infection: Time to Put Patients First,” Lancet Infectious Diseases 16/9 (2016).

[11] See, for example, Medicines Patent Pool, “VaxPaL,” https://medicinespatentpool.org/what-we-do/vaxpal.

[12] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Waiver from Certain Provisions of the TRIPS Agreement for the Prevention, Containment and Treatment of COVID-19, IP/C/W/669 (2020).

[13] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Waiver from Certain Provisions of the TRIPS Agreement for the Prevention, Containment and Treatment of COVID-19: Revised Decision Text, IP/C/W/669/Rev.1 (2021).

[14] K. Cullinan, “WTO Head Welcomes Compromise on IP Waiver for COVID Vaccines—But Activists and Pharma Express Dismay,” Health Policy Watch (March 16, 2022), https://healthpolicy-watch.news/wto-head-welcomes-ip-waiver-compromise/; World Trade Organization, “Director-General Okonjo-Iweala Hails Breakthrough on TRIPS COVID-19 Solution,” World Trade Organization (March 16, 2022), https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news22_e/dgno_16mar22_e.htm.

[15] Cullinan (see note 14).

[16] World Trade Organization, Ministerial Conference Twelfth Session, Draft Ministerial Decision on the TRIPS Agreement, WT/MIN(22)/W/15/Rev.2 (2022).

[17] Ibid.

[18] F. Fischer, D. Torgerson, A. Durnova, and M. Orsini, “Introduction to Critical Policy Studies,” in F. Fischer, D. Torgerson, A. Durnova, and M. Orsini (eds), Handbook of Critical Policy Studies (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2015).

[19] J. Fereday and E. Muir-Cochrane, “Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development,” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5/1 (2006).

[20] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade Related-Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Waiver from Certain Provision of the TRIPS Agreement for the Prevention, Containment, and Treatment of COVID-19, IP/C/W/669 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade Related-Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Waiver from Certain Provision of the TRIPS Agreement for the Prevention, Containment, and Treatment of COVID-19, IP/C/W/669/Rev.1 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Minutes of Meeting on 15–16 October and 10 December 2020, IP/C/M/96 (2021), World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Minutes of Meeting on 15-16 October and 10 December 2020, IP/C/M/96/Add.1 (2021), World Trade Organization, Council for Trade Related-Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Waiver from Certain Provision of the TRIPS Agreement for the Prevention, Containment, and Treatment of COVID-19, IP/C/W/672 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade Related-Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Waiver from Certain Provision of the TRIPS Agreement for the Prevention, Containment, and Treatment of COVID-19, IP/C/W/671 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade Related-Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Waiver from Certain Provision of the TRIPS Agreement for the Prevention, Containment, and Treatment of COVID-19, IP/C/W/673 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade Related-Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Waiver from Certain Provision of the TRIPS Agreement for the Prevention, Containment, and Treatment of COVID-19, IP/C/W/674 (2021); World Trade Organization, General Council, Minutes of Meeting on 16–18 December 2020, WT/GC/M/188 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Minutes of Meeting on 23 February 2021, IP/C/M/97 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Minutes of Meeting on 23 February 2021, IP/C/M/97/Add.1 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Minutes of Meeting on 10–11 March 2021, IP/C/M/98 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Minutes of Meeting on 10–11 March 2021, IP/C/M/98/Add.1 (2021); World Trade Organization, General Council, Minutes of Meeting on 1–2 and 4 March 2021, WT/GC/M/190 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Minutes of Meeting on 30 April 2021, IP/C/M/99 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Minutes of Meeting on 30 April 2021, IP/C/M/99/Add.1 (2021); World Trade Organization, General Council, Minutes of Meeting on 5–6 May 2021, WT/GC/M/191 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Minutes of Meeting on 8, 9, and 29 June 2021, IP/C/M/100 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Minutes of Meeting on 8, 9, and 29 June 2021, IP/C/M/100/Add.1 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Minutes of Meeting on 20 July 2021, IP/C/M/101 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Minutes of Meeting on 20 July 2021, IP/C/M/101/Add.1 (2021); World Trade Organization, General Council, Minutes of Meeting on 27–28 July 2021, WT/GC/M/192 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Minutes of Meeting on 4 October 2021, IP/C/M/102 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Minutes of Meeting on 13–14 October, 5, 18, and 29 November, and 16 December 2021, IP/C/M/103 (2021); World Trade Organization, General Council, Minutes of Meeting on 7–8 October 2021, WT/GC/M/193 (2021); World Trade Organization, General Council, Minutes of Meeting on 15 December 2021, WT/GC/M/195 (2021); World Trade Organization, General Council, COVID-19 and Beyond: Trade and Health, JOB/GC/251/Rev.1 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Draft General Council Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health in the Circumstances of a Pandemic, IP/C/W/681 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Urgent Trade Policy Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis: Intellectual Property, IP/C/W/680 (2021); World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Waiver from Certain Provisions of the TRIPS Agreement for the Prevention, Containment and Treatment of COVID-19, IP/C/W/684 (2021); World Trade Organization, General Council, COVID-19 and Beyond: Trade and Health, WT/GC/W/823/Rev.6 (2021).

[21] Médecins Sans Frontières, “Countries Obstructing COVID-19 Patent Waiver Must Allow Negotiations to Start 2021” (March 9, 2021), https://www.msf.org/countries-obstructing-covid-19-patent-waiver-must-allow-negotiations.

[22] World Trade Organization, “Global Business/Civil Society Response to COVID-19,” https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/covid19_business_e.htm; Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, “The TRIPS COVID-19 Waiver,” https://policyalternatives.ca/newsroom/updates/trips-covid-19-waiver.

[23] UNICEF, “COVID-19 Vaccine Market Dashboard,” https://www.unicef.org/supply/covid-19-vaccine-market-dashboard; E. Sagonowsky, “The Top 20 Pharma Companies by 2020 Revenue” Fierce Pharma (March 29, 2021), https://www.fiercepharma.com/special-report/top-20-pharma-companies-by-2020-revenue.

[24] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Minutes of Meeting on 10–11 March 2021, IP/C/M/98/Add.1 (2021, see note 20).

[25] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Minutes of Meeting on 30 April 2021, IP/C/M/99/Add.1 (2021, see note 20).

[26] Ibid.

[27] World Trade Organization General Council, Minutes of Meeting on 7–8 October 2021, WT/GC/M/193 (2021, see note 20).

[28] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Minutes of Meeting on 23 February 2021, IP/C/M/97/Add.1 (2021, see note 20).

[29] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade Related-Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Waiver from Certain Provision of the TRIPS Agreement for the Prevention, Containment, and Treatment of COVID-19, IP/C/W/684 (2021, see note 20).

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Minutes of Meeting on 10–11 March 2021, IP/C/M/98/Add.1 (2021, see note 20).

[33] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Minutes of Meeting on 15–16 October and 10 December 2020, IP/C/M/96/Add.1 (2021, see note 20).

[34] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Minutes of Meeting on 10–11 March 2021, IP/C/M/98/Add.1 (2021, see note 20).

[35] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Minutes of Meeting on 15–16 October and 10 December 2020, IP/C/M/96/Add.1 (2021, see note 20).

[36] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Minutes of Meeting on 23 February 2021, IP/C/M/97/Add.1 (2021, see note 20).

[37] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Urgent Trade Policy Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis: Intellectual Property, IP/C/W/680 (2021, see note 20).

[38] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Minutes of Meeting on 23 February 2021, IP/C/M/97/Add.1 (2021, see note 20); World Trade Organization, General Council, Minutes of Meeting on 27–28 July 2021, WT/GC/M/192 (2021, see note 20).

[39] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Minutes of Meeting on 8, 9, and 29 June 2021, IP/C/M/100/Add.1 (2021, see note 20).

[40] Ibid.; World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Minutes of Meeting on 15-16 October and 10 December 2020, IP/C/M/96/Add.1 (2021, see note 20).

[41] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Minutes of Meeting on 15–16 October and 10 December 2020, IP/C/M/96/Add.1 (2021, see note 20).

[42] J. Whattam, “It’s Time for Canada to Support the WTO TRIPS Waiver,” MonitorMag (May 6, 2021), https://monitormag.ca/articles/its-time-for-canada-to-support-the-wto-trips-waiver.

[43] Médecins Sans Frontières, “Compulsory Licenses, the TRIPS Waiver and Access to COVID-19 Medical Technologies” (2021), https://msfaccess.org/sites/default/files/2021-05/COVID_TechBrief_MSF_AC_IP_CompulsoryLicensesTRIPSWaiver_ENG_21May2021_0.pdf.

[44] Ibid.; Médecins Sans Frontières, “WTO COVID-19 TRIPS Waiver: Doctors Without Borders Canada Briefing Note,” https://www.doctorswithoutborders.ca/sites/default/files/msf_canada_briefer_on_trips_waiver.pdf.

[45] Statement on Copyright and Proposal of a Waiver from Certain Provisions of the Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement for the Prevention, Containment and Treatment of COVID-19, IP/C/W/669 (2021), https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/civil_society_vaccines_waiver_e.pdf.

[46] Ibid.

[47] World Health Organization, “Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the 2021 SADC Seminar on TRIPS Waiver” (2021), https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-2021-sadc-seminar-on-trips-waiver—23-november-2021; Caritas Internationalis, “CI Orientations on COVID-19 Vaccines,” https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/caritas_e.pdf.

[48] Statement on Copyright and Proposal of a Waiver from Certain Provisions of the Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement for the Prevention, Containment and Treatment of COVID-19, IP/C/W/669 (2021, see note 45); Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, “Civil Society Letter Supporting India’s and South Africa’s Proposal for a TRIPS Agreement Waiver for COVID-19 Treatments” (2021), https://www.policyalternatives.ca/newsroom/updates/civil-society-letter-supporting-indias-and-south-africas-proposal-trips-agreement; Caritas Internationalis, “COVID-19 Vaccines Must Be Made Available for All with Equity and Justice” (2021), https://www.caritas.org/2021/03/vaccinepatents/.

[49] Statement on Copyright and Proposal of a Waiver from Certain Provisions of the Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement for the Prevention, Containment and Treatment of COVID-19, IP/C/W/669 (2021, see note 45); Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (2021, see note 48); Caritas Internationalis (2021, see note 48).

[50] Médecins Sans Frontières, “Open CSO Letter to WTO Trade Ministers: Do Not Accept the Current Draft, Demand a Real Waiver” (2022), https://msfaccess.org/open-cso-letter-wto-trade-ministers-do-not-accept-current-draft-demand-real-waiver; Médecins Sans Frontières, “CSO Letter to EU on the Reported Draft Text of the TRIPS Waiver Negotiation” (2022), https://msfaccess.org/cso-letter-eu-reported-draft-text-trips-waiver-negotiation.

[51] Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, “Civil Society Letter Supporting India’s and South Africa’s Proposal for a TRIPS Agreement Waiver for COVID-19 Treatments” (2021, see note 48).

[52] A. Bourla, “An Open Letter from Pfizer Chairman and CEO to Colleagues,” Pfizer (2021), https://www.pfizer.com/news/articles/why_pfizer_opposes_the_trips_intellectual_property_waiver_for_covid_19_vaccines; L. Burger and S. Nebehay, “Drugmakers Say Biden Misguided over Vaccine Patent Waiver,” Reuters (May 6, 2021), https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/pharmaceutical-association-says-biden-move-covid-19-vaccine-patent-wrong-answer-2021-05-05/; International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations, “IFPMA Statement on WTO TRIPS Intellectual Property Waiver” (2021), https://www.ifpma.org/resource-centre/ifpma-statement-on-wto-trips-intellectual-property-waiver/; International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations, “IFPMA Statement on TRIPS Discussion Document” (2022), https://www.ifpma.org/resource-centre/statement-ifpma-trips-discussion-document/; PhRMA, “PhRMA Letter to President Joseph Biden 2021” (2022), https://patentdocs.typepad.com/files/2021-03-05-phrma-letter.pdf.

[53] F. Jordans, “Vaccine Maker BioNTech Says No Need to Waive Patents,” ABC News (May 10, 2021), https://abcnews.go.com/Business/wireStory/vaccine-maker-biontech-waive-patents-77601343.

[54] International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (2021, see note 52); PhRMA (see note 52).

[55] Bourla (see note 52); Burger and Nebehay (see note 52); International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (2021, see note 52); International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (2022, see note 52); PhRMA (see note 52).

[56] Bourla (see note 52).

[57] International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (2021, see note 52); PhRMA (see note 52).

[58] International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (2022, see note 52).

[59] Bourla (see note 52).

[60] Ibid.

[61] B. Eakin, “J&J’s Chief Patent Atty Says COVID IP Waiver Won’t Work,” Law360 (April 22, 2021), https://www.law360.com/articles/1375715/j-j-s-chief-patent-atty-says-covid-ip-waiver-won-t-work.

[62] I. Reić, “Vaccinating the World: Op-Ed by Iskra Reic,” AstraZeneca (July 1, 2021) https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/articles/2021/vaccinating-the-world-op-ed-by-iskra-reic.html.

[63] ‘t Hoen et al. (see note 10); Médecins Sans Frontières, “Patents, Prices and Patients: The Example of HIV/AIDS” (2002), https://www.msf.org/patents-prices-patients-example-hivaids.

[64] J. Harrelson, “TRIPS, Pharmaceutical Patents, and the HIV/AIDS Crisis: Finding the Proper Balance between Intellectual Property Rights and Compassion,” Widener Law Symposium Journal (2001).

[65] A. S. Y. Wong, C. B. Cole, and J. C. Kohler, “Intellectual Property and Access to Medicines: Mapping Public Attitudes toward Pharmaceuticals during the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) Negotiation Process,” Globalization and Health 17/92 (2021).

[66] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Minutes of Meeting on 10–11 March 2021, IP/C/M/98/Add.1 (2021, see note 20).

[67] World Trade Organization, Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Waiver from Certain Provisions of the TRIPS Agreement for the Prevention, Containment and Treatment of COVID-19, IP/C/W/684 (2021, see note 20).

[68] See A. S. Y. Wong, C. B. Cole, and J. C. Kohler, “TRIPS Flexibilities and Access to Medicines: An Evaluation of the Barriers to Employing Compulsory Licenses for Patented Pharmaceuticals at the WTO,” South Centre Research Series No. 168 (October 2022), https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/RP168_TRIPS-Flexibilities-and-Access-to-Medicines_EN.pdf.

[69] Cullinan (see note 14); J. Love, “QUAD’s Tentative Agreement on TRIPS and COVID 19” (2022), https://www.keionline.org/37544.

[70] M. Mishra and E. Michael, “J&J pulls COVID Vaccine Sales Forecast Due to Low Demand, Supply Glut,” Reuters (April 19, 2022), https://www.reuters.com/business/johnson-johnson-suspends-sales-forecast-covid-19-vaccine-2022-04-19/.