Volume 21/1, June 2019, pp 115 – 127

Corey McAuliffe, Ross Upshur, Daniel W. Sellen, and Erica Di Ruggiero

Abstract

There is a dearth of research that aims to understand graduate students’ lived experience of global health practice. Difficulties, distress, and trauma occur before and after these students’ placement abroad, and they often increase when returning home. Moreover, few articles address the increased vulnerabilities faced by women, such as sexual violence and gender-based discrimination. We conducted a phenomenological study to understand the lived experience of Canadian and US women graduate students participating in global public health practice. Eight participants participated in 21 in-depth interviews, while 17 participants created 35 lived experience descriptions through a guided writing exercise. Our findings reveal participants’ underlying discomfort with privilege while conducting fieldwork abroad, as well as depressive feelings once they return home. According to participants, while their global health fieldwork challenged previous ways of thinking and being, limited spaces and avenues for openly sharing these processes contributed to mental health challenges. Participants reported that these interviews were their first opportunity to fully share their global health experiences. Based on our analysis of these shared experiences, we argue that academic institutions participating in global health should provide appropriate and accessible resources, adequate financial compensation, safe spaces for authentic conversations, and time for processing experiences throughout the research cycle and especially in the months and years following fieldwork.

Introduction

Content warning: this article includes content and references pertaining to traumatic and distressing experiences of individuals, including sexual violence.

With the growth of global health programs across the United States and Canada, more students are seeking out international fieldwork experiences.[1] Master’s and doctoral programs are foundational spaces for learning and preparation for practice. However, the short- and long-term effects of this work are unknown, and our understanding of student experience remains inadequate. Since global health is an interdisciplinary field of study, we reviewed the literature on all (non-clinical) graduate students’ participation in global health fieldwork within the Global South.[2] We found no identifiable literature pertaining to public health graduate student experience; however, the literature illustrates that graduate students participating in global health fieldwork face difficult and challenging situations before, during, and after fieldwork.[3] While some risk and discomfort is implicitly assumed during fieldwork, students identified traumatic and distressing experiences that were silenced and suppressed and that left them feeling isolated, often exacerbated once they returned home.[4] Fieldwork may be perceived as a positive experience overall, but it can also leave students with feelings of anxiety, depression, and, in extreme instances, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[5] Numerous cases of sexual violence and harassment against women participating in global health fieldwork are documented, but there is a paucity of accounts specific to public health students’ experiences.[6] The primary researcher’s own tacit beliefs of safety in the workplace were challenged and forcibly deconstructed after a personal traumatic experience during academic global health fieldwork. This occurrence magnified a void regarding how others have dealt with similar experiences. This paper aims to break that silence and suggests that universities have an ethical duty of care for all students.

Personal and professional impact on students

Many global public health training opportunities in the Global South are located in unfamiliar or precarious environments, where students regularly undertake unpaid or underpaid work with limited support and resources.[7] Considerations for student safety are needed before, during, and following fieldwork. However, attention appears to be disproportionately focused on the period prior to departure, even though many professionals argue that re-entry is the most important stage of the international experience.[8] Moreover, university-based pre-departure trainings can be missing or inadequate.[9] According to Amy Pollard, not one student from her multi-university study found their pre-departure training to be satisfactory, claiming that it was “useless” and that they received “zero preparation for actual fieldwork.”[10] Within our study, half of the interview participants reported that there was no pre-departure training available or they had not been made aware of one.

Once home, students often receive requests to recount their experiences in both professional and personal settings. There appears to be institutional and personal bias toward documenting positive, transformative outcomes, often cultivated and oriented for curriculum vitae, awards, and scholarship opportunities.[11] This is more challenging in a context where graduate students are not in positions of power (compared to faculty members, field site supervisors, and administrators), which can lead to feelings of isolation and being overwhelmed, the exploitation of labor, and issues of sexual harassment and assault.[12] Moreover, students may suppress negative and traumatizing experiences, given that they are often precariously employed, further limiting safe academic spaces where they may openly and vulnerably share.[13]

Gendered impacts on women in global health

Women in global health face additional stereotypes, oppression, reproductive health barriers, gender inequities, and sexual violence compared to their male counterparts. In relation to family planning (such as (in)fertility, childbearing, and parenting), some women face further strains, which can be intensified when working in malaria- or Zika-endemic countries.[14] Women may be forced to disclose sensitive information that they otherwise are not ready to share. Gender inequities further affect women through increased financial stress stemming from disproportionate pay and labor.[15]

While numerous cases of sexual violence and harassment against women conducting global health fieldwork have been documented, Valery Ridde et al. note that the “issue has received little attention in academic global health.”[16] A report by the Women in Global Health Research Initiative found that “twenty-six percent of women report having experienced unwanted physical contact while doing international field research.”[17] The Survey of Academic Field Experience: Trainees Report Harassment and Assault further found that “64% of female respondents experienced sexual harassment, while 20% were victims of sexual assault” and that the “perpetrators were most often senior male research team members.”[18] Women’s future academic careers are negatively affected by sexual violence through increased mental health challenges and decreased productivity, which further constrains funding opportunities.[19] While sexual violence remains prevalent in US and Canadian academic settings, current programs and policies have started to address this; however, additional attention is required, beyond the merely local institutional level, to reduce sexual violence within the global health field. Research also shows that repercussions go beyond women who are targeted by harassment, affecting colleagues and creating a toxic work environment.[20] These occurrences continue to be highly stigmatized, silenced, and inadequately addressed, which can lead to varied emotional, spiritual, physical, and mental health outcomes.[21] Our research study revealed multiple effects on women who underwent such experiences, including (but not limited to) fear, depression, anxiety, isolation, self-blame, and PTSD.

Methodology

This research study used philosophical, theoretical, and methodologically aligned qualitative research to better understand human behavior and embodiment. Our study was situated within Max van Manen’s qualitative methodology known as “phenomenology of practice.”[22] This hermeneutic interpretive approach aims to better understand lived experience, privileging participant knowledge through their experience of living- or being-in-the-world, and offering a holistic perspective that is inclusive of emotional, embodied, existential, and pathic ways of knowing.[23]

Phenomenology of practice

A phenomenology of practice seeks to identify “practical acts of living, accessed through ‘narratives’ (interviews and observations) to reveal meaning,” increasing awareness of lived experience, “rather than providing theory for generalization or prediction of phenomena.”[24] This tension exists for students, as what is learned in the classroom is often quite different from what is required in fieldwork practice. Phenomenological accounts offer an opportunity to reflect on practice, challenging the supremacy of cognitive understanding, by embracing a deeper empathic sense of being-in-the-world.[25] Consequently, phenomenology can affect an individual’s experience or an institution’s understanding of the phenomenon, as it may offer new meaning structures, language for a foreign experience, and new ways to describe, conceive of, and respond to global health fieldwork.[26]

Research question

Our central research question was the following: What is the lived experience of US and Canadian women graduate students participating in global public health practice? We sought to understand experiential opportunities and challenges, while creating space for open and honest dialogue on global public health practice.

Methods

This qualitative study involved the collection of lived experience descriptions (LED) through in-depth phenomenological interviews (IDPIs) and a guided writing exercise (GWE). A LED is a “vivid textual account of an experience” that aims to recall “a particular instance of an experience in concrete personal terms avoiding abstraction (possible introductions, rationalizations, causal explanations, generalizations, or interpretations).”[27] To not further silence or suppress students’ experiences, participation in the GWE was open to any eligible participant.

Study setting and participants

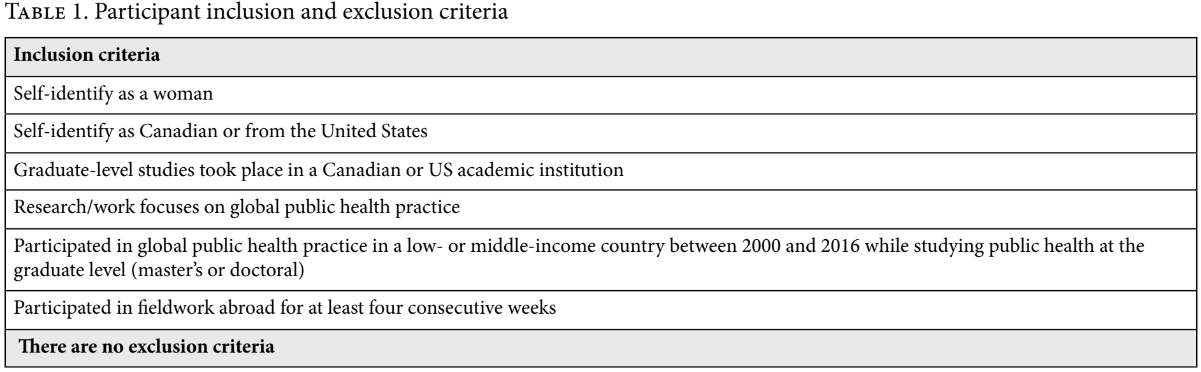

We conducted our study in Canada and the United States between January and October 2018. Inclusion criteria responded to the temporal and cultural context of global public health practice (see Table 1).

Participant recruitment and participation

We employed purposive sampling to recruit participants, through email and social media recruitment. Of the 49 women who expressed interest, 4 were ineligible. While 13 potential participants completed an IDPI pre-interview, only 8 were selected to participate in the IDPIs. Seventeen participants contributed through the GWE, submitting 35 LEDs. Since in-person interviews are favorable to building trust, our travel feasibility, financial means, and accessibility to participants influenced our choice of study participants and interview locations. Those outside of North America were invited to participate in the GWE.

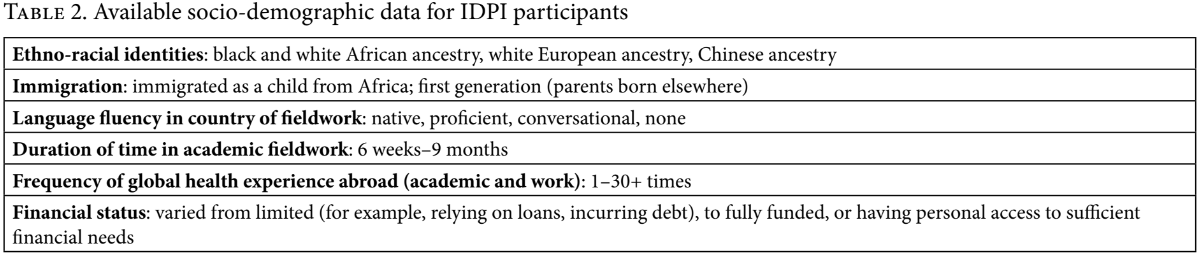

Given that representativeness is not the objective of phenomenology, we selected eight participants from the pre-interviews to allow for multiple (two to three) IDPIs with each participant. Heterogeneity was maximized through the selection process (for example, university attended, country of origin, length of time spent abroad, country of fieldwork, and area of expertise) within a fairly homogenous group. From the IDPIs, participants came from varied backgrounds (see Table 2). We did not explicitly collect sociodemographic data (for example, race, age, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation), as our research aimed to better understand participants’ lived experiences. Participants’ stories reflect experiences in more than 20 countries, including sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. The 25 study participants attended a total of 14 different universities for master’s or doctoral studies, completing their graduate-level international fieldwork between 2010 and 2016.

Data creation, analysis, and interpretation

Informed by van Manen, our hermeneutic phenomenological analysis sought to explore participants’ experiences through the co-construction of narrative accounts, recognizing the self and other as entwined.[28] While participants deeply engaged with their own lived experiences, the primary researcher acted as a “central figure who influences the collection, selection, and interpretation of data”; thus, our research was “regarded as a joint product of the participants, the researcher, and their relationship: It [was] co-constituted.”[29] Our data generation focused on detailed descriptions rather than cognitive considerations or reflections of participants’ experiences.[30]

Our analytic process aligned with Linda Finlay’s four key processes to phenomenological sensibility: “seeing afresh, dwelling, explicating, and languaging.”[31] By “seeing afresh,” we incorporated a deep reflexive position, stepping back from the data rather than stepping away from it. In “dwelling,” we read and re-read (listened and re-listened to) the data as a whole and in segments, identifying particular points, meanings, and preliminary themes from personal accounts. This was supported through reflective inquiry using five existential guides (explained below).[32] Through “explicating,” we created overarching themes, meaning structures, and stories. In phenomenology, a theme is “much less a singular statement (concept or category) than an actual description of the structure of a lived experience,” as no one account can capture the totality of an experience.[33] Our stories were thus rooted in “salient excerpts that characterize specific common themes or meanings across informants” rather than specific accuracy toward the experience of one individual.[34] As part of our interpretive analysis, we crafted stories from verbatim IDPI transcripts to draw attention to multiple or hidden meanings.[35] Exemplars from these stories are highlighted in the findings below. We used “languaging” through writing and re-writing that was rooted in existentiality, not theory.[36] This type of qualitative writing identifies an openness to other plausible experiences, focusing on iconic (recognizable) as opposed to empirical validity. Such shared experiences offer an emotional and compelling technique that allows readers to better comprehend lived experiences, sometimes more effectively than lived life.[37] Throughout our study, we incorporated reflexivity through reflexive journaling, field notes, data co-creation, and regular in-depth conversations with colleagues.

Pathic knowledge and existential guides

An examination of a person’s pathic knowledge is derived from their pre-cognitive habits, empathic or sympathic understandings, gut feelings, memories, and situational experiences. Pathic knowledge, as a phenomenological concept, captures the “non-cognitive” and emotional ways in which we know, necessitating a shift to conceptualize emotions as rational.[38] Thus, phenomenological stories help shed light on things that are taken for granted, hidden, silenced, or at times suppressed.[39] We applied Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Max van Manen’s five existential guides—relationality, corporeality, spatiality, temporality, and materiality—to allow for the identification of what is often perceived as ambient or background noise.[40] Since these existential ways of knowing are often tacit, our application and guided reflection influenced our research question, data-creation tools (interview and guided writing guides, use of audio recorders, and use of computers), transcription methods, participant and researcher experiences, and analytic processes (reflexively, conceptually, and thematically).

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the University of Toronto’s Research Ethics Board. Formal written consent was obtained from each participant. Consent was understood to be ongoing and continually negotiated and was thus verbally revisited at the beginning of each additional interview. Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any point; however, no participants withdrew.

Findings and implications: Overarching themes

The key themes that emerged in our study include discomfort with privilege, mental and physical health challenges, sexual violence and harassment, witnessing or experiencing violence, reproductive health and fertility, travel safety and transportation, a lack of preparedness, financial burdens and stress, peer relationships as protective, and being heard. Our findings show that while the experience of global public health practice by women graduate students is varied and complex, participants have deep-rooted commonalities. While individual experiences were unique, emotional reactions and responses to these experiences appear cross-cutting among multiple—or at times, all—participants interviewed. Many of these underlying responses or deep-seated feelings (that is, themes) also appeared in the GWE.

This article covers three overarching themes (sexual violence and harassment, discomfort with privilege, and being heard), and one subtheme within mental and physical health challenges (depression). Each theme is described below, with exemplars. At the end of each exemplar we list the participant’s initials; the region where the person undertook fieldwork (note that the East African region includes the Horn of Africa); and the data source for the exemplar (IDPI or GWE). These findings reflect the dynamic and evolving understandings of global public health practice.

Sexual violence, harassment, and gender discrimination

Participants experienced various forms of sexual violence, including assault, harassment, gender discrimination, and fear of personal safety due to their sexual orientation. Participants experienced these forms of violence from individuals in positions of power (for example, preceptors, doctors, government officials, and organizational directors), from colleagues, in public spaces, and in communities where they lived.

My first few global health experiences were filled with sexual harassment and violence, from men in positions of authority. It took me a long time to see that pattern and realize I didn’t do anything wrong. I was always trying to fix myself to fit into global health. Talking to other women who had similar experiences made me feel like maybe we are not the problem. (EM, East Africa, IDPI)

One afternoon, a woman made a joke about me marrying my preceptor, who was the head of a women’s empowerment NGO, so that he could move to North America with me. I was very uncomfortable and my whole body tensed as each muscle flexed. My preceptor started cracking up and joined in on the joke. The experience stayed with me throughout my practicum, especially when my preceptor made very sexist comments about women. When I would get to work and he wasn’t there, I felt relieved. (SS, Southern Africa, GWE)

While in Central America, my driver, who I’d respected, pulled me behind a door and started kissing me. I was startled. I pushed him away and kept my distance from him afterwards. I remember thinking, “Whoa. I don’t know what just happened, why that happened, or how to avoid having that happen again.” After it happened, I never told anyone about it, and blamed myself. Now, with #MeToo, I realize it’s really common. (RK, Central America, IDPI)

Women who reported experiencing sexual violence or gender discrimination often noted that they did not share this information with others, as they felt they had done something wrong or could have prevented the experience from happening. Women further reported that they attempted various mitigation tactics (for example, wearing oversized clothes, carrying pepper spray, taking different routes home each day, and wearing a fake wedding ring), especially when traveling alone.

Two participants who identified as LGBTQ noted fearing for their safety in countries where homosexuality was illegal.

I asked a local clinician to complete a specific study-related questionnaire. He made a snide remark that he would only do it if I took him out for a drink. I said no. So he did not complete the questionnaire. When my co-investigator found out, he made a joke about my sexuality, “Tell him you like people who wear dresses.” This made me nervous for my safety, as homosexuality is a criminal offense. Due to this experience, I returned home early. (DA, Southern Africa, GWE)

After being followed through the woods by a man, having several cabbies pay undue attention to me, and the NGO’s director sexually harass me, my anxiety heightened into terror. The sexual harassment and re-triggering of a sexual assault turned my stomach into anxious knots. Like a ball of yarn unraveling, I realized why I was coming apart so quickly: I wasn’t able to be myself. It was a toxic mix—being a woman and having no local friends or support. When my partner came to visit, I had to conceal my love and affection for her, as homosexuality was illegal in the country. I had to pretend to have a boyfriend and speak about him instead of her. I realized how quickly my identity was removed. It felt like everything that was me, was not allowed. (GN, South Asia, GWE)

It is evident from the exemplars above that women who identify as LGBTQ experience intersectional oppressions. GN reported that she shared her story with the primary researcher only because she felt she could trust her. DA also expressed that she felt willing to share her story due to the primary researcher’s student status. Due to the trauma of GN’s fieldwork in South Asia, she stated, “I do not want to go back into the field. I do not want to continue in global health research.” As we aimed to capture the experiences of women in general, it is imperative to gain further and deeper insight into the experiences of LGBTQ individuals participating in global health, in order to create a safe and inclusive work environment for all.

Discomfort with privilege

Discomfort due to privilege was discussed by every IDPI participant and also raised in many guided writing exercises, despite participants’ different backgrounds and experiences. This was most often expressed in reference to participants’ position as residents of the Global North, and it included similar feelings from all participants, even those who completed fieldwork in countries of familial origin. Participants questioned the inequities they witnessed, why their work was deemed more valuable than that of local community members, and the benefits they received while abroad and once home. These feelings of inequity also led participants to recognize a fissure or dissonance in their “two worlds.”

My fieldwork left me questioning: What do I do with this information? Why are women in this country going through so much? Why do I have the privileges I have? Even though I am not really privileged in North America, when I did my fieldwork, it was clear how privileged I was. Sitting in between these two worlds is really hard. Some of these women have the same name as me, or our family members are cousins. But their parents weren’t able to get out like my parents. That one thing alone means we lived completely different lives. I could have been that woman. (GF, East Africa, IDPI)

The concept of having one foot in two different worlds was held by multiple participants, regardless of whether they had familial relations in their country of fieldwork. They felt like they were simultaneously living two lives, never feeling whole.

I feel like I’m living two lives right now. I have one full life there: friends, family, who I work with, where I work, and what I spend my time doing. And I have all of that here too. It’s completely disintegrated. I try to integrate them, but it doesn’t work. So much of my heart, mind, body, spirit and energy is still over there. The more I go and come back, I am only half a person. (TA, West Africa, IDPI)

Participants reported experiencing negative mental health impacts—including depression, loss of energy, and disconnect from previous support systems—as a result of their unease with privilege and its effect on their sense of self (two lives) and spatial and geographic groundedness (two worlds). This unease further affected their fieldwork experiences and left them questioning the appropriateness of unexpected benefits during fieldwork.

I stayed with family members while doing my fieldwork. They are really well off. They had all these people working for them, and I benefited from that every day. I felt so uncomfortable. It was mainly young people who aren’t going to be educated, who are cooking my food, cleaning my clothes, and getting me any little thing that I need. I already felt so privileged being there. I didn’t want to feel that privilege on top of it. I thought about that every single day. Here I am with my little pieces of paper, doing my research, and talking to people. That’s my work. And they’re waking up at dawn to cook food, make tea, make bread, serve people, sweep the entire compound, and clean up after everyone. I found that really hard. It made me think, “How is my work of more value than the work they’re doing? But they work way harder than me.” (GF, East Africa, IDPI)

Many participants experienced feelings of depression and frustration but could not speak freely to others in academic settings. Feelings of guilt, including professional benefits, were exacerbated when they returned home. This was acutely felt when these women published and presented their findings, recognizing the juxtaposition between fancy conference hotels and the conditions of the communities where they conducted their research. Their hyperawareness of inequities led some participants to feel that their difficulties were invalid or not “bad enough” to warrant the time and space needed for processing their experiences. While these challenges have been documented in the humanitarian aid literature, their impact on future practice has not previously been studied.[41] In addition, most of the relevant writing on global health fieldwork has focused on anxiety and isolation rather than depression.[42]

Mental health challenges: Depression

Participants reported a wide variety of mental health challenges, including witnessing or experiencing trauma or violence, sensitive data collection, moral distress, and a lack of time to process and reflect on experiences. Further mental health challenges related to returning home included anxiety, feelings of being overwhelmed (connected to school), panic attacks, and PTSD. Many participants’ experiences of discomfort with privilege and feelings of depression also intensified as they returned home.

The depression I felt after my global health experience was a coming to terms with the harsh realities and stark disparities of the world. I was trying to figure out how to make sense of the suffering I witnessed, while coming back to my shiny city and all the comforts of a really nice life in North America. (RK, Western Africa, IDPI)

For those who sought out mental health services, they often did not know how to proceed or where to find accessible and affordable services. As shown below, some attempted to utilize university services but felt that their efforts were dismissed.

People asked me, “So, how was it? Tell me all the things.” I couldn’t articulate to someone who wasn’t there what it was like. I should’ve been happier to be back, but I was in a weird funk. It lasted a few months, to the point where I thought, “This is not okay. I need to seek help.” Not because I was worried, I was just really depressed every day. It was gross. At one point, I went to the university and tried to get a referral to a counselor, and it was brutal. There was nothing. I was reaching out. I was trying to seek help, and it was not taken seriously at all. (HK, East Africa, IDPI)

When counseling services were offered to HK, it was not until four months later. Meanwhile, the only other immediate option available to her was to call the university’s crisis hotline, which was not appropriate for her needs. RM (South America, IDPI) reported never seeking out university counseling, as it was common knowledge on campus that appointments were available only if booked months in advance. Some participants reported not seeking outside support as they went through the process of trying to understand what they had witnessed or experienced, while others reported not feeling ready to share, being unsure of whom to share it with, or feeling that others would not understand their experience. Participants noted that these experiences shifted their sense of self and at times exacerbated mental health challenges. For example, once returned home, data analysis led some participants to feel overwhelmed, isolated, anxious, and re-traumatized.

After I came back was the most depressing period of my life. It was gray and cold out. I felt disconnected, because we didn’t have classes anymore. All my close friends had moved, and all I did was work on my thesis. I didn’t have much human interaction. I felt so depressed. I didn’t want to wake up. Certain stories were at the forefront of my mind every day. The fact that my research was my sole responsibility was really tough. I was alone constantly. (GF, East Africa, IDPI)

Arriving home, I was distraught from day one. I was angry at people around me. I picked fights. I boiled inside every time a friend asked me how my “trip” was, as if I’d gone on vacation. As I returned back to school and started my data analysis and write up, anxiety and depression set in. (GN, South Asia, GWE)

A fundamental shift in one’s self was a common experience reported by participants, who expressed feeling alone and not understood. This idea is connected to other participants’ expression of simultaneously living in “two worlds.” For some, returning to the data meant facing memories from a challenging time period. For others, the experience of analyzing data was connected to a lack of time and space in which to process and realize the depth of their experiences and emotional reactions to them. Depressive feelings are temporally bound and often triggered when participants return home, especially once they revert back to a typical (past) schedule. While the intensity of depressive feelings seems to lessen with time, these feelings can continue to drain energy as they play softly in the background.

Being heard

In RK’s first interview, she identified feeling that her global health experiences were very positive overall. In our second interview, after being asked how she felt after the first interview, she replied:

I’m surprised by how much these conversations brought up things I hadn’t thought about in a long time, and in ways I hadn’t considered. It brought up emotions I wasn’t anticipating. I felt, “Wow, this is some stuff I haven’t fully processed yet,” when I believed I had finished processing it years ago. I’m grateful for the opportunity to reflect, and surprised at how much it impacted me, even days later. I hadn’t thought my experiences were intense. I had compartmentalized them and thought of them as normal global health experiences. But then again, it is the norm for global health. But it’s not normal. Or not the way it needs to be. (RK, South America, IDPI)

RK’s reflection elucidates an important conception of the global health experience—what is normal? Others recognized challenging or traumatizing fieldwork experiences through accumulating “badges of honor” or “joining the club.” Women are often reluctant to identify these experiences as negative for fear that they “failed” the test.[43] In this way, participants sometimes found ways to make the stories palatable or funny—or, more often, they remained silent or shared their stories selectively.

Many participants related later in the IDPIs that the interviews were the first opportunity they had to fully share their experience. While most had been in settings where they were able to share a handful of core stories, many participants never found a welcoming or acceptable space to share their whole experience. This included those who sought (and accessed) counseling, who reported feeling that their counselor was ill equipped or asked irrelevant questions.

This process is therapeutic. It’s rare that I get to speak to somebody that has traveled, let alone to a similar part of the world and has the same training or understanding of global health. I really appreciate your listening. A lot of the things we talked about, I’ve never talked to anyone about. Little pieces, but never as much to any one person, ever. It’s heavy. I still deal with a lot of it. I feel like I’m drowning in it. (TA, West Africa, IDPI)

Participants expressed how important it was to openly share their story beyond a clinical mental health framing, noting the positive benefits experienced through this research study.

The importance of your research is clear for me. No one gets the opportunity to reflect like this unless it’s framed as problematic. And then you have to talk to someone for your own mental health, and even that is difficult to do. It’s a positive experience for me to reflect back on all of this. I hope to use this experience to shape the way I do future work. (HK, East Africa, IDPI)

This is the most delayed therapy, it made me think about how it’s okay to be sitting with these feelings. I’m sure there are other people sitting with these feelings and have been for a long time. It’s so important that spaces are held for people to come in and talk about these things. (GF, East Africa, IDPI)

We explicitly chose a phenomenological approach with the knowledge that IDPIs and GWEs might cause participants to “feel discomfort, anxiety, false hope, superficiality, guilt, self-doubt, irresponsibility—but also hope, increased awareness, moral stimulation, insight, a sense of liberation, a certain thoughtfulness.”[44] The exemplars above indicate that reflective questioning and the creation of spaces to be heard appear to be beneficial in multiple ways. As revealed by RK’s exemplar, she began to realize the ways in which she had been suppressing parts of her stories only after being given the opportunity to deeply reflect.

Ethics of global health education: Students as workers

The question of who is responsible for students’ safety and well-being while participating in global public health fieldwork has not been adequately addressed. While some academics suggest that responsibility should rest with institutional review boards or research ethics boards, this would likely place the onus on the researcher (that is, the student) and relieve the university of accountability.[45] However, when reflecting on the ethical reasoning and need for the these boards (which are designed to protect human research subjects’ rights and welfare), we must also question why similar protections have not been put in place for researchers. Do researchers not deserve the same protections as their participants? Discussions about this important consideration need to take place at both home and host institutions.

Many existing regulations and policies protect workers, such as researchers. However, students’ employment status is varied and often not protected under legislation. With the rise in global health fieldwork, we suggest that both home and host institutions should be ethically obliged to keep students healthy and well supported, just as these institutions are obligated to do for their employees. Graduate students (whether paid, unpaid, or underpaid), in essence, are workers with rights, especially when completing fieldwork. According to Bronwyn McBride et al., around “70% of unpaid and underpaid internships in the social sciences and the UN system are undertaken by young women.”[46] This can result in exploitative work and highlights the issue of gender equity within this student rights issue.[47]

While rarely discussed, the idea of students as workers is not new. Multiple local, national, and global documents make statements or raise arguments to support this idea. In Ontario, Canada, the Occupational Health and Safety Act’s definition of worker was expanded to include students in November 2014.[48] Thus, the “employer has a duty to provide these unpaid workers [students] with information, instruction and supervision, and to take every precaution reasonable in the circumstances to protect their health and safety.”[49] With regard to the United States, Katherine Durack argues that most unpaid internships at for-profit firms are considered illegal under the US Fair Labor Standards Act. She further questions the appropriateness of the exemptions that most government agencies and nonprofit organizations receive.[50] Article 23 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment” and that “everyone, without any discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work.”[51] McBride et al. also point out that the “routine devaluing of women’s labour promotes the feminisation of poverty, and undermines progress towards Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 on gender equality and SDG 8 on decent work and economic growth.”[52] While academic institutions have identified ethics training as core to global health education, most do not have robust policies or procedures for protecting students’ health and safety.[53] By considering students as workers, universities could apply an occupational health and safety framework to support and protect students during global health practice.

Resonance and rigor

Rigorous phenomenological research is aligned with empathy and humility, two components of global health ethics, which can also intersect with gender. Effective phenomenological writing occurs when the reader finds the story to be plausible, to be something she feels she could vicariously experience, or to be related to something she has experienced, while also capturing study participants’ realities.[54] This is known as the “phenomenological nod,” or imagining one’s self in another’s shoes.[55] This concept is analogous to Sarah Tracy’s idea of “resonance,” aimed at achieving excellent qualitative research through the “ability to meaningfully reverberate and affect an audience.”[56] Our research study aims to offer the reader a new way to describe, conceive of, and respond to individual experiences. These new structures of meaning permit critical and vital questions to arise through empathizing and sharing stories, which can be expressed or withheld, along gendered lines. By giving voice to the lived experience of women graduate students, this study presents academic public health institutions with the opportunity to better recognize, validate, respond to, and support students and practitioners participating in global public health practice.

Limitations and strengths

While some phenomenological critics argue that “the appeal to emotions and anecdote is an illegitimate philosophical move,” we would agree with Havi Carel that “emotion and anecdote are fundamental building blocks of human experience.”[57] In this study, we sought to elicit an emotional and empathetic response from the reader. While a possible limitation, we view it as an inherent strength that allows for an understanding of fluidity, ambiguity, relationality, and situational and dynamic research processes.

One study limitation is that our chosen phenomenon, global health practice, is a vast and complex topic involving a range of people, places, and institutions. While our research offers insights into this phenomenon as experienced by our participants, it not does not offer deeply detailed understandings of just one type of experience (for example, the student experience of their institution’s role in global public health practice, or the experience of sexual assault). Since global public health practice had yet to be explored, we chose to focus on the topic as a whole in the hope that future research will address compelling findings from our study. Due to financial and time constraints, we intentionally limited our population group in order to have deeper and richer reflections. The amount of data collected, however, far surpasses a singular verbatim transcript, and the creation of the GWE allowed us to capture additional participants’ voices.

We also recognize that participants may not fully feel that they are co-creators or collaborators. This is especially true for participants with sensitive and distressing stories, those who are still embedded in their trauma, and those who have distanced themselves altogether from global health. While participants were actively engaged in data creation, we acknowledge that we wield power in decisions regarding the research process (for example, picking study objectives and attending to some stories and not others) and that we may have missed significant data. Our reflexive practice throughout this rigorous phenomenological project was critical.

Conclusion

This study is the first of its kind, adding a valuable contribution to the literature through a fuller understanding of global public health practice. Initial recruitment led to almost 50 responses in fewer than two weeks. The response and data generated indicate that women want to share their stories. However, as research demonstrates, women need to feel that they have a safe environment in which to do so. Our research allows for deeper understanding and meaning-making, with the hope that future researchers will continue to explore this phenomenon from multiple perspectives.

Further examination of our findings reveals a crucial need to better understand the lived experiences of oppressed groups (for example, LGBTQ individuals, gender non-conforming individuals, persons with disabilities or chronic or episodic health conditions, and racially marginalized minorities), undergraduate and international students, and students living outside the United States and Canada. Research on the experience of faculty (precarious and tenured), other staff, and postdoctoral workers also needs exploration in order to make effective, holistic, and supportive institutional changes. Further methodological research, such as institutional ethnography, can explore the effects of intersectionality, power, and privilege on actors at home universities and host institutions. More explicit theoretical frameworks need to focus on further understanding gendered and racialized dynamics of global health practice. As illustrated, phenomenology gives voice and space to other ways of knowing and brings attention to silences or taken-for-granted experiences. The consideration of who is responsible for women graduate students’ health and well-being in global public health practice is a critical student rights and gender equity issue. As a result, academic institutions need to consider their ethical duty of care to students, treat them as workers with rights, and offer better support though appropriate and accessible resources, safe spaces and time for processing experiences, and more authentic and open conversations throughout the research process.

Corey McAuliffe, MPH, is a PhD candidate in the Division of Social and Behavioural Health Sciences, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Canada.

Ross Upshur, MA, MD, is head of the Clinical Public Health Division, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Canada.

Daniel W. Sellen, MA, PhD, is director of the Joannah and Brian Lawson Centre for Child Nutrition, University of Toronto, Canada.

Erica Di Ruggiero, MHSc, PhD, is director of the Office of Global Public Health Education and Training, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Canada.

Please address correspondence to Corey McAuliffe. Email: corey.mcauliffe@mail.utoronto.ca.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2019 McAuliffe, Upshur, Sellen, and Di Ruggiero. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

[1]. A. I. Matheson, J. Pfeiffer, J. L. Walson, and K. Holmes, “Sustainability and growth of university global health programs” (2014). Available at http://csis.org/publication/sustainability-and-growth-university-global-health-programs.

[2]. C. McAuliffe, R. Upshur, D. W. Sellen, and E. Di Ruggiero, “Critical reflections on mental well-being for post-secondary students participating in the field of global health,” International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction (2018), pp. 1–13.

[3]. Ibid.

[4]. Ibid. See, for example, A. Pollard, “Field of screams: Difficulty and ethnographic fieldwork,” Anthropology Matters 11/2 (2009), pp. 1–23; J. Paulson, N. Hopwood, L. McAlpine, and D. Mills, “Untold doctoral experiences: Research findings and recommendations from a study into the challenges of doctoral study,” Studies in Higher Education 37/6 (2009), pp. 667–681.

[5]. See, for example, E. Sohn, “Health and safety: Danger zone,” Nature 541/7636 (2017), pp. 247–249; M. Surya, D. Jaff, B. Stilwell, and J. Schubert, “The importance of mental well-being for health professionals during complex emergencies: It is time we take it seriously,” Global Health: Science and Practic 5/2 (2017), pp. 188–196.

[6]. B. McBride, S. Mitra, V. Kondo, et al., “Unpaid labour, #MeToo, and young women in global health,” Lancet 391 (2018) pp. 2192–2193; K. Ross, “‘No sir, she was not a fool in the field’: Gendered risks and sexual violence in immersed cross-cultural fieldwork,” Professional Geographer 67/2 (2015), pp. 180–186; V. Ridde, C. Dagenais, and I. Daigneault, “It’s time to address sexual violence in academic global health,” BMJ Global Health (2019), pp. 1–4.

[7]. McBride et al. (see note 6).

[8]. B. La Brack and L. Bathurst, “Anthropology, intercultural communication, and study abroad,” in M. Van de Berg, R. Paige, and L. Hemmings (eds), Student learning abroad: What our students are learning, what they’re not, and what we can do about it (Sterling, VA: Stylus, 2012), pp. 188–214.

[9]. McAuliffe et al. (see note 2); Paulson et al. (see note 4); Pollard (see note 4).

[10]. Pollard (see note 4), p. 18.

[11]. Ibid., p. 15.

[12]. See, for example, Pollard (see note 4); S. T. Kloß, “Sexual(ized) harassment and ethnographic fieldwork: A silenced aspect of social research” Ethnography 18/3 (2016), pp. 396–414; V. Congdon, “The ‘lone female researcher’: Isolation and safety upon arrival in the field,” Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford 7/1 (2015), pp. 15–24.

[13]. Ridde et al. (see note 6).

[14]. McAuliffe et al. (see note 2).

[15]. McBride et al. (see note 6).

[16]. Ridde et al. (see note 6), p. 1. See, for example, E. Moreno, “Rape in the field, reflections for a survivor,” in D. Kulick and M. Wilson (eds), Taboo: Sex, identity, and erotic subjectivity in anthropological fieldwork (London: Routledge, 1995), pp. 169–189; G. Sharp and E. Kremer, “The safety dance: Confronting harassment, intimidation, and violence in the field,” Sociological Methodology 36/1 (2006), pp. 317–327; K. Ross, “‘No sir, she was not a fool in the field’: Gendered risks and sexual violence in immersed cross-cultural fieldwork,” Professional Geographer 67/2 (2015), pp. 180–186.

[17]. Center for Global Health, Women in global health research initiative. Available at https://www.womenglobalhealth.com/about-us.

[18]. K. B. Clancy, R. G. Nelson, J. N. Rutherford, and K. Hinde, “Survey of academic field experiences (SAFE): Trainees report harassment and assault,” PLoS One 9/7 (2014), cited in McAuliffe et al. (see note 2), p. 7.

[19]. A. Fairchild, L. Holyfield, and C. Byington, “National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report on sexual harassment: Making the case for fundamental institutional change,” JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association 320/9 (2018), pp. 873–874; H. McLaughlin, C. Uggen, and A. Blackstone, “The economic and career effects of sexual harassment on working women,” Gender and Society 31/3 (2017), pp. 333–358; Ridde et al. (see note 6).

[20]. McLaughlin et al. (see note 19), p. 352.

[21]. Kloß (see note 12); McAuliffe et al. (see note 2); Moreno (see note 16).

[22]. M. van Manen, “Phenomenology of practice,” Phenomenology and Practice 1/1 (2007), pp. 11–30; M. van Manen, Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing (New York: Routledge, 2014).

[23]. M. van Manen, Researching lived experiences (London: State University of New York Press, 1990).

[24]. J. D. Crist and C. A. Tanner, “Interpretation/analysis methods in hermeneutic interpretive phenomenology,” Nursing Research 52/3 (2003), p. 202.

[25]. Ibid.

[26]. H. Carel, Illness: The cry of the flesh (Stocksfield: Acumen, 2013).

[27]. M. A. van Manen, “Phenomenology of Practice” (workshop at the 23rd Annual Qualitative Health Research Conference, Quebec City, Canada, October 16, 2017).

[28]. van Manen (2014, see note 22); Carel (2013, see note 26).

[29]. L. Finlay, “‘Outing’ the researcher: The provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity,” Qualitative Health Research 12/4 (2002), p. 531.

[30]. van Manen (2014, see note 22).

[31]. L. Finlay, “Engaging phenomenological analysis,” Qualitative Research in Psychology 11/2 (2014), p. 121.

[32]. Ibid., p. 135.

[33]. M. van Manen. “Doing” phenomenological research and writing: An introduction (Edmonton: University of Alberta, 1984), p. 21.

[34]. Crist and Tanner (see note 24), p. 204.

[35]. S. Crowther, P. Ironside, D. Spence, and L. Smythe, “Crafting stories in hermeneutic phenomenology research: A methodological device,” Qualitative Health Research 27/6 (2017), pp. 826–835.

[36]. Finlay (2014, see note 31).

[37]. van Manen (1990, see note 23).

[38]. J. Shaw and D. Connelly, “Phenomenology and physiotherapy: Meaning in research and practice,” Physical Therapy Reviews 17/6 (2012), pp. 398–408.

[39]. Crowther et al. (see note 35); K. Lopez and D. Willis, “Descriptive versus interpretive phenomenology: Their contributions to nursing knowledge,” Qualitative Health Research 14/5 (2004), pp. 726–735.

[40]. M. Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of perception (London: Routledge, 2013); van Manen (2014, see note 22).

[41]. McAuliffe et al. (see note 2).

[42]. Ibid.

[43]. S. Delamont, “Familiar screams: A brief comment on ‘Field of Screams,’” Anthropology Matters 11/2 (2009), p. 1.

[44]. van Manen (1990, see note 23), p. 162.

[45]. D. Dominey-Howes, “Seeing ‘the dark passenger’: Reflections on the emotional trauma of conducting post-disaster research,” Emotion, Space and Society 17 (2015), pp. 55–62.

[46]. McBride et al. (see note 6), p. 2192.

[47]. Ibid.

[48]. Occupational Health and Safety Act, Ontario, Canada, Bill 18 (2014). Available at https://www.ola.org/en/legislative-business/bills/parliament-41/session-1/bill-18.

[49]. Ontario Ministry of Labour, FAQs: Definition of “worker” in the Occupational Health and Safety Act (2015). Available at https://www.labour.gov.on.ca/english/hs/faqs/worker.php.

[50]. K. Durack, “Sweating employment: Ethical and legal issues with unpaid student internships,” College Composition and Communication (2013), p. 246.

[51]. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, G.A. Res. 217A (III) (1948), art. 23.

[52]. McBride et al. (see note 6), p. 2192.

[53]. A. D. Pinto and R. E. Upshur, “Global health ethics for students,” Developing World Bioethics 9/1 (2009), pp. 1–10; K. A. Stewart, “Teaching corner: The prospective case study,” Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 12/1 (2015), pp. 57–61.

[54]. B. Raingruber and M. Kent, “Attending to embodied responses: A way to identify practice-based and human meanings associated with secondary trauma,” Qualitative Health Research 13/4 (2003), pp. 449–468; van Manen (2014, see note 22).

[55]. van Manen (1990, see note 23).

[56]. S. Tracy, “Qualitative quality: Eight ‘big-tent’ criteria for excellent qualitative research,” Qualitative Inquiry 16/10 (2010), p. 844.

[57]. H. Carel, The phenomenology of illness (Oxford University Press, 2016), p. 7.