Volume 21/1, June 2019, pp 239 – 252

Sarah L. Bosha, Michelle Adeniyi, Jenna Ivan, Roya Ghiaseddin, Fabakary Minteh, Lamin F. Barrow, and Rex Kuye

Abstract

In January 2007, former president of The Gambia Yahya Jammeh created the Presidential Alternative Treatment Program (PATP), which introduced a fraudulent “HIV cure.” PATP and the fraudulent HIV herbal cure (PATP cure) were widely advertised in state media through patient testimonials and specially produced broadcasts of Jammeh administering treatment, enticing people living with HIV to join the program. Jammeh faced little to no opposition from within The Gambia. Due to the great power and influence he wielded, PATP was nothing short of a health dictatorship. This paper argues that PATP and the PATP cure violated the human rights of people living with HIV in The Gambia and compromised HIV health service delivery. In addition, during PATP’s 10-year operation, the global health community was derelict in its duty to stop Jammeh’s promotion and use of the PATP cure and to protect people living with HIV.

Introduction

In past years, fraudulent HIV cures supported by the highest levels of state have emerged in various countries.[1] In January 2007, then Gambian president and dictator Yahya Jammeh announced that he had received a “mandate from God” to create an HIV and AIDS herbal cure from seven herbs found in the Qur’an.[2] He announced, “Mine is not an argument, mine is a proof. It’s a declaration. I can cure AIDS and I will.”[3]

Jammeh created the Presidential Alternative Treatment Program (PATP) to distribute his fraudulent HIV cure (PATP cure). PATP operated from 2007 to 2016, when Jammeh was voted out of power.[4] Jammeh refused to have his cure subjected to scientific testing for efficacy and safety.[5] Instead, he sent the blood samples of his first nine patients to a laboratory in Senegal to prove that the PATP cure worked. Although the results showed only the CD4 levels of the patients, Jammeh argued that these levels were proof of efficacy. Officials at the Senegalese university who conducted the testing refuted Jammeh’s claim, explaining that no conclusion of the effectiveness of his herbal cure had been made.[6] They remarked, “It’s dishonest of the Gambian government to use our results in this way.”[7]

Jammeh has no medical training, holds only a high school diploma, and is from a family well known in The Gambia for herbal remedies.[8] When he first began PATP, it was to cure HIV and AIDS. Later, Jammeh’s PATP claimed to also cure diabetes, infertility, and cancer, among other diseases. In this paper, PATP is used to refer to the program’s focus on people living with HIV, and the PATP cure refers exclusively to the unscientifically proven and untested HIV “cure” promoted by Jammeh.

Jammeh claimed that his PATP cure could eradicate HIV from the body in just three days. At the time of the introduction of his PATP cure in 2007, the number of people living with HIV in the Gambia was 18,000.[9] This number rose steadily to 21,000 by 2018.[10]

The first cohort of PATP patients was a mixture of people who chose to enter PATP and people who joined under duress. PATP patient cohorts were grouped according to their date of arrival and were given strict instructions for their participation, including discontinuation of antiretroviral medications and abstention from sex, caffeine, alcohol, and kola nuts.[11] Patients were also forbidden from eating or drinking anything from outside the PATP facilities or receiving visitors.[12] In violation of privacy rights and patient confidentiality, the names, faces, CD4 counts, and viral loads of patients were published on an official website promoting and providing information about the program.[13] It is unknown exactly how many people living with HIV enrolled in PATP. Tasmir Mbowe, former director general and self-proclaimed clinical expert of PATP, speaking before the Janneh Commission in 2018, claimed that only 311 HIV positive people enrolled in PATP during its 10 years.[14] The claim of only 311 patients contradicted Mbowe’s statements to the Gambian press in 2016, when he claimed that 9,000 patients had been given herbal cures for various ailments, with the majority of them being treated for HIV.[15] In 2009, researchers reported that more than 200 HIV-positive people had been treated in the program.[16] The figures are unknown and debatable because the records of the exact numbers of those enrolled and who died in PATP have not been released. It is unclear whether proper records of patients’ arrivals, discharges, or deaths were even kept during the duration of PATP.

Mbowe’s medical qualifications legitimized PATP, as he publicly spoke in favor of the alleged success of the PATP cure.[17] As the program’s director general, he was responsible for recruiting patients.[18] Not all Gambian officials in the health sector approved of PATP. For example, two individuals—the director and the administrator of the National AIDS Secretariat—resigned in protest of the PATP cure.[19] Jammeh appointed a new director of the secretariat, who saw “the President’s treatment as ‘complementary’ to conventional [antiretroviral] care” and was careful not to openly or directly oppose [PATP], arguing that Jammeh’s support was necessary to halt HIV and AIDS prevalence rates.”[20]

Internationally, opposition to Jammeh was weak and failed to protect people living with HIV in The Gambia from the PATP cure. The United Nations (UN) responded to the PATP cure by issuing a statement through its United Nations Development Programme country director, Fadzai Gwaradzimba, in February 2007.[21] This statement challenged Jammeh to subject the cure to testing by a team of international experts and urged people living with HIV “to continue to comply with their treatment regimens while the efficacy of the new treatment is being assessed.”[22] For that criticism, she was ordered by the government to leave The Gambia in 48 hours.[23] Thereafter, the international global health community issued a handful of press releases and then fell into silence, watching as the chaos unfolded and the first cohort of nine HIV-positive people enrolled in PATP, becoming human subjects for the PATP cure.[24]

In the end, the absence of powerful opposition locally and internationally provided the setting for Jammeh to create and preside over a health dictatorship in a political environment that lacked protection mechanisms for people living with HIV and led unknown numbers to their deaths. Prosper Yao Tsikata, Gloria Nziba Pindi, and Agaptus Anaele state that “the curtailment of individuals’ right to make an input into how certain health policies affect their lives, reveals that political dictatorship translates into health dictatorship.”[25] This paper defines health dictatorship as the abuse of power by a political leader or governmental authority that results in undermining patients’ autonomy to make informed health decisions based on widely available scientifically sound information and treatment options. Jammeh’s health dictatorship through PATP resulted in the violation of patients’ right to health and other human rights; flagrant disregard for medical ethics, including a denial of full disclosure and information about the PATP cure; and the undermining of patient autonomy and confidentiality. In addition, Jammeh created a climate of fear that intimidated health care workers and policy personnel working on HIV, thereby affecting the quality of health care services for people living with HIV.

The true impact of the PATP cure on the lives of people living with HIV had not been assessed since Jammeh left the country for self-imposed exile in Equatorial Guinea on January 22, 2017.[26] In 2018, in collaboration with AIDS-Free World, we carried out a mixed-method research study for six weeks to examine the impact of the PATP cure in The Gambia. Our quantitative research surveyed a sample of people living with HIV to determine the impact of PATP on their lives and their health-seeking behavior. The study also examined factors affecting enrollment in PATP. To investigate the program’s impact on health service delivery and HIV policy, we conducted qualitative research to elicit the views of individuals working in the HIV policy and the health care sector.

Ethical approval for this research project was provided in the United States by the University of Notre Dame Institutional Review Board and in The Gambia by the Medical Research Council/Gambia Government Joint Ethics Committee.

Methodology

Qualitative research

The qualitative research portion of our study examined the impact of the 10-year promotion of PATP on health services for people living with HIV and on HIV policy implementation in The Gambia. We conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews lasting 14–45 minutes each with 15 HIV health care workers and 9 HIV policy implementers. Participants were identified via snowball sampling.

Health care workers participating in the study were required to have worked with people living with HIV before and during PATP so they could discuss changes in health care provision over time. These workers included doctors, nurses, counselors, and community workers. Specific antiretroviral clinics, hospitals, and HIV care centers were identified prior to interviews because not all health facilities provide HIV services. Unfortunately, those who worked directly in PATP declined to participate in the study.

For policy implementers and policy makers, the inclusion criteria were that the person either influenced or was involved in HIV policy creation before and during the implementation of PATP. Through consultation with local partners, we identified the Ministry of Health, World Health Organization, Medical Research Council, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), National AIDS Secretariat, National AIDS Control Program, Gambia Network of AIDS Support Societies as key players in HIV policy. We conducted four pilot interviews prior to research implementation to refine the survey tool.

We developed an initial codebook for content analysis, with patterns and themes identified based on open coding.[27] We used both emic and etic analysis. Emic analysis consisted of codes made from participants.[28] For example, during the interviews, the term “defaulters”—meaning people who left conventional HIV care—became a noticed pattern, and we thus used the term as code. Etic analysis—consisting of codes created based on our perspectives as researchers—was used more often.[29] We managed and analyzed the data using a qualitative data analysis program, NVivo Version 11. Links, nodes, and memos were used in the coding process through an examination of transcripts and field notes. We built explanatory themes by sorting and synthesizing the initial codes, categories, and themes. Transcribed interview data and field notes were transferred into PDF formats and uploaded to NVivo for analysis. Coding was stopped when saturation was reached.

Quantitative study

Of the 182 people living with HIV surveyed, 53 were men and 129 were women. The sociodemographic information collected included gender, ethnicity, age, marital status, and education level. We recruited participants from two urban towns (Brikama and Serrekunda) and four rural towns (Sibanor, Bwiam, Soma, and Farfenni). We chose these sites due to their proximity to support societies for people living with HIV. Only four participants were recruited from an antiretroviral treatment site in Brikama to get a subset of people living with HIV who may not be members of an HIV support society. Our inclusion criteria were that the person be over the age of 18 and have been aware of their HIV status during the existence of the program (2007–2016).

We developed a survey and were guided by the Global HIV Strategic Information Working Group, which suggests the inclusion of investigation questions about both demographics and HIV services uptake (access to counseling and testing, knowledge of serostatus, access to care and treatment, and retention in care).[30] Our survey was divided into five sections: (1) sociodemographic information, (2) health information, (3) general practices relating to HIV, (4) knowledge and perceptions of PATP, and (5) factors involved in PATP enrollment. We used the Likert scale to format the questions and accurately gather information on this complex subject matter (from 1 = “strongly disagree to 5 = “strongly agree”), multiple-choice questions, and open-response questions. Prior to initiating the formal surveys, we conducted pilot surveys to modify the wording of questions and the response structure. Our data excluded participants who had never heard of PATP (n=4) and whose surveys were incomplete (n=1). We administered the survey orally in the major languages spoken in The Gambia: English, Mandika, Wolof, Jola, and Fula.

Mobile devices utilizing Ona Mobile Data Collection stored responses in the field through Open Data Kit. We analyzed data using the Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences software (version 25.0). Free-response answers were grouped into general themes. We conducted X2 tests of independence to determine which variables were associated with participants’ perceptions of PATP and their PATP involvement. When analyzing variations between ethnic groups, we grouped Serer, Serahuli, and Others together due to their low response rate.

Results

Nearly half of the health care workers surveyed (7/15) reported that many of their patients who tried PATP died. Many health care workers (10/15) noticed a decline in patient population because of the PATP cure announcement. Most health care workers (14/15) stated that one impact of PATP was that less funding was available to incentivize staff serving people living with HIV in conventional HIV treatment settings. Health workers’ general belief, though unconfirmed, was that monies for staff serving people living with HIV were being diverted to PATP. Almost half of the health care workers (7/15) reported that coworkers suddenly left their hospital or clinic to work in PATP, where they were paid better salaries.

Most health care workers (11/15) reported feeling uncomfortable telling patients there was no cure for HIV; they feared that this information would get back to Jammeh and they would be punished. A minority of health care workers (3/15) reported actively speaking against the PATP cure to their patients. All nine policy implementers interviewed reported that during PATP’s operation, they did not feel safe speaking out against the PATP cure.

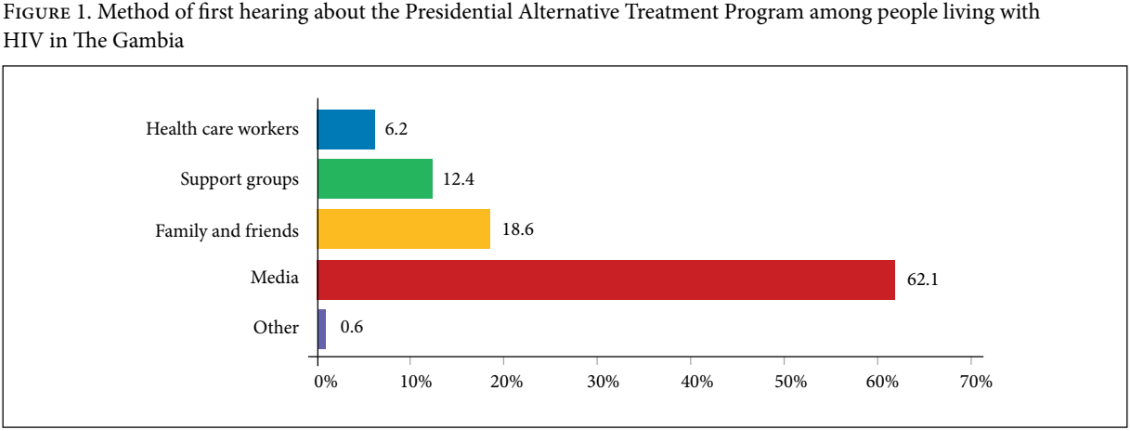

For the quantitative portion of our study, we surveyed 182 individuals living with HIV. Of these, 177 had heard about PATP while 5 reported that they had never heard about the program. Among the 177 who were aware of PATP, 168 did not participate in the program and 9 did. The majority of former PATP patients (7/9) strongly agreed* that people joined PATP voluntarily; the remainder (2/9) slightly agreed that participation was voluntary. Similarly, the majority of former enrollees (6/9) strongly disagreed that patients could freely leave PATP if they no longer wanted to participate, and most (5/9) had not felt comfortable asking questions about their treatment. The majority of the 182 individuals surveyed (62.1%) reported first hearing about PATP through the media. Figure 1 shows the methods through which these individuals learned about PATP.

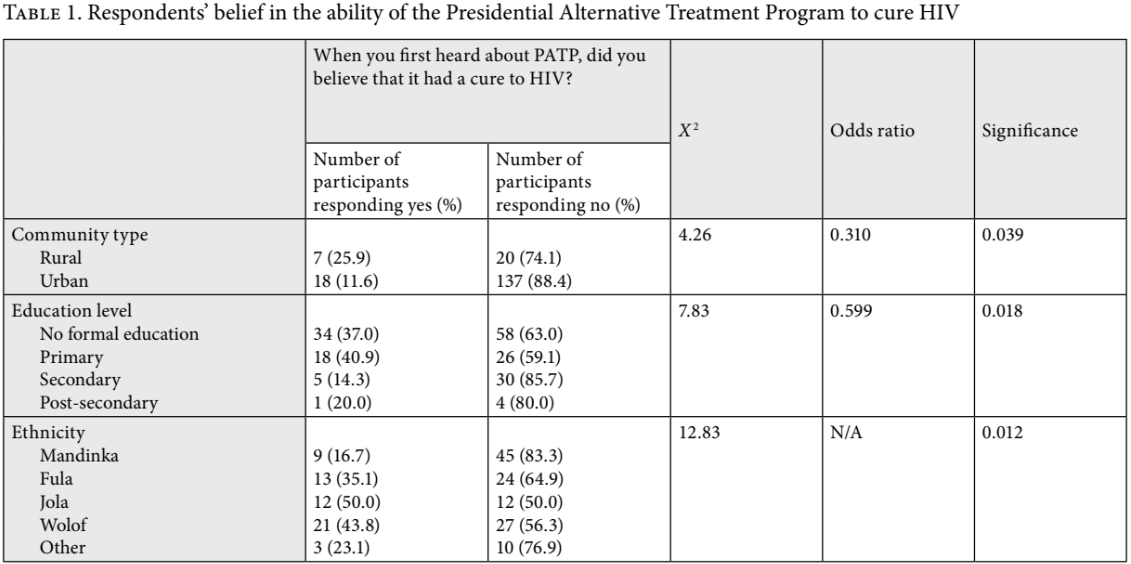

After hearing about PATP for the first time, 61.8% stated that they did not hold PATP in high regard, while 28.3% did. A third of participants (32.7%) initially believed that PATP had a cure for HIV and 67.2% did not believe that it had a cure. Table 1 summarizes key findings about participants’ perceptions on whether PATP had a cure.

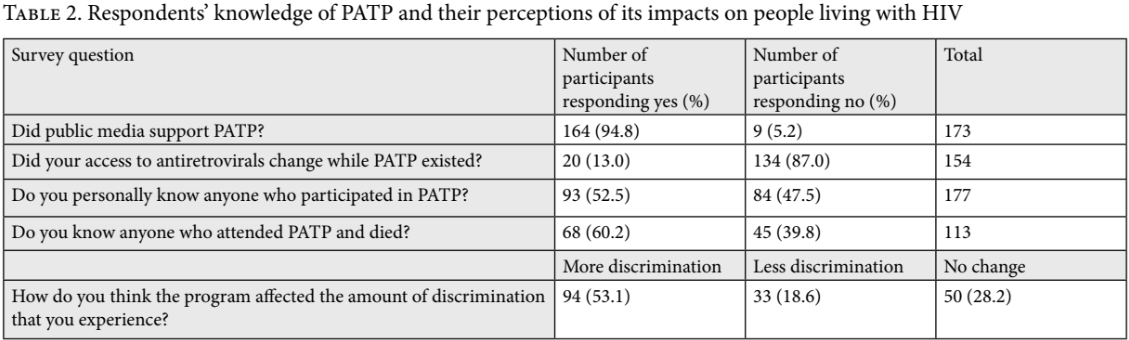

More than half of the respondents (53.1%) reported that PATP led to more discrimination against people living with HIV, while 28.2% reported that there was no change in the amount of discrimination they experienced. A staggering 94.8% of all participants surveyed believed that the public media supported PATP. Table 2 shows participants’ knowledge of PATP and their perceptions of its impacts on people living with HIV.

The majority of respondents (82.4%) reported that health care workers were their main source of information on HIV. The second most reported source of information was from support groups (14.3%), followed by television and radio (1.1%). Our data analysis found that people living with HIV diagnosed prior to or in 2007, the year when PATP was introduced, were 2.74 times more likely than those diagnosed after 2007 to receive advice not to mix traditional medicine with prescribed treatment (RR = 2.74, 95% CI [1.02, 7.34]).

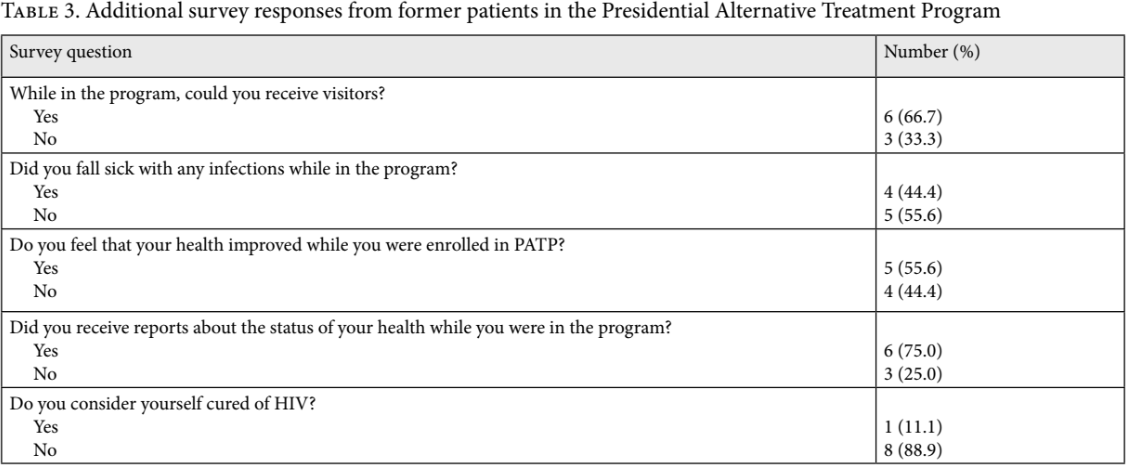

Of those surveyed, only nine had been patients at PATP, resulting in low statistical power for generalization among this group. However, these nine individuals provided critical insights concerning PATP’s impact on their lives. For example, eight of them did not consider themselves cured of HIV, and four fell sick with other infections while in the program. Our background research found that patients in PATP were given a bitter herbal concoction that resulted in physical and mental side effects that included constant diarrhea, vomiting, and hallucinations, leaving most in great discomfort for the duration of their stay.[31] Despite the majority (8/9) believing they were not cured by Jammeh’s program, five reported feeling that their health had improved during their enrolment in PATP. More than half of them (5/9) did not feel comfortable asking questions about their treatment. Table 3 below shows additional responses about the program given by the nine individuals who had participated in it.

Discussion

Three former PATP patients have filed a civil suit in the High Court of The Gambia against Jammeh.[32] The suit argues that PATP violated the Gambian Constitution in that patients were subjected to cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, and that their confinement in PATP amounted to false imprisonment. The suit also argues that PATP had an adverse impact on the health of these patients.

Indeed, PATP was a major violation of the right to health. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights provides that everyone has the right “to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.”[33] The right to health is defined as including the right to control one’s health and body; the right to be free from interference, such as non-consensual medical treatment and experimentation; and “the right to seek, receive and impart information and ideas concerning health issues.”[34] With respect to the right to health, states have the responsibility to provide scientifically approved drugs and medically appropriate services that respect confidentiality and medical ethics.[35]

Jammeh’s PATP cure disrupted decades of HIV campaign work and “negatively impacted vital HIV services and research partnerships resulting in a significant reduction in competent personnel and services in HIV facilities and suboptimal HIV care with frequent medication stock outs and several patients having their antiretroviral regimens switched often.”[36] The program also introduced policies contrary to The Gambia’s national HIV response, resulting in conflicting and confusing messages on HIV management and care.

PATP and the PATP cure flouted Gambian ethical procedures on the development and introduction of new medicines. The PATP cure was given to human subjects without first complying with established national standards for drug testing, contrary to policies of the Ministry of Health and section 9 of the HIV and AIDS Prevention Act (HIV Act).[37] The program strictly forbade people living with HIV from taking their antiretroviral medications, which ran contrary to the government’s policy commitment to ensure that all people living with HIV were given antiretroviral treatment, as well as section 10 of the HIV Act (promulgated in 2015, the year prior to Jammeh’s electoral defeat), which prohibits spreading false information about HIV and promoting medicines that lack scientifically proven efficacy or that falsely claim to cure HIV.[38] Encouraging people living with HIV to abandon their antiretrovirals endangered public health because of the increased likelihood of the virus spreading within the general population as a result of seropostive people believing they had been cured.

Health care workers and HIV policy implementers reported that PATP created a climate of fear, as Jammeh took extreme action to punish anyone critical of the PATP cure, curtailing the freedom to openly receive and impart information about HIV.[39] Even as late as 2015, the UN Special Rapporteur on torture reported that “a layer of fear … was visible on the faces and in the voices of many … from civil society and this even extended to some Government officials.”[40] Due to this hostile environment, Gambian HIV experts could not openly challenge or pressure Jammeh to give up the PATP cure—for many, doing so would have resulted in arrest, threats, or even death. The expulsion of senior UN official Gwaradzimba after she publicly criticized the PATP cure had a chilling effect on the community of those working on HIV.[41] As one policy implementer remarked to us during an interview, “After [Gwaradzimba] was expelled, people from other organizations kept their mouths shut … They do not want to anger the president and be [exiled], or arrested, or even go missing. You know, because at the time of Jammeh, these things happened constantly. You say something bad about him, and you are done” (interview 22).

This fear among health care workers and policy implementers seriously compromised the quality of HIV-related services, as well as access to information for people living with HIV. Information sharing is critical to the effective management and treatment of HIV, which relies greatly on each patient’s ability to access, understand, and apply health information.[42] Health care workers admitted that they did not dissuade patients from trying the PATP cure and changed the manner in which they counseled people living with HIV. These workers could not openly or fully discuss HIV treatment with their patients. One antiretroviral clinic nurse remarked, “Jammeh had ears everywhere, and if he found out that you were saying bad things about his treatment, you’d get fired or jailed or worse. So even though I knew it was bogus, I did not tell my patients this … Out of fear!” (interview 15). One nurse who decided to speak against PATP suffered backlash from the Jammeh administration, which threatened to investigate him for suspected wrongdoing in the provision of care for people living with HIV.

In further violation of the free flow of information, the national media was used as a propaganda tool to promote the success of the PATP cure and encourage enrollment. It is likely that after watching, reading, or hearing such propaganda in the media, people living with HIV then sought information from another member of their community to validate what they heard.[43] PATP patients and their testimonials validating the effectiveness of the cure on the national broadcasting station, Gambia Radio Television Services (something that many later asserted was a lie induced by fear), likely also influenced people’s enrollment in the program.[44] Between PATP’s years of operation from 2007 to 2017, while the media promoted the program, conventional health care systems held to the scientifically proven notion that HIV was incurable and that antiretroviral medicines were the only option that could prolong life and manage the disease. This created a confusing environment with mixed and often conflicting messages on HIV being provided to the public.

Although Jammeh and Gambian experts argued that PATP propaganda had the benefit of reducing the social stigma of being HIV positive, many people living with HIV whom we surveyed reported that they experienced the same or increased levels of discrimination because of the program.[45] Surprisingly, Gambian HIV experts have also argued that one positive impact of PATP was increased uptake of antiretroviral medications.[46] Oddly, Jammeh promoted PATP while also supporting the National AIDS Secretariat, which was responsible for coordinating the efforts of clinics, nonprofits, and other organizations to provide conventional antiretroviral treatment.[47] Fortunately, the majority of survey respondents confirmed that there was no change in access to antiretroviral medications during PATP.

Despite these positive reports of uninterrupted access to antiretroviral treatment, PATP violated international standards on the quality of HIV-related care. According to the World Health Organization, people living with HIV “should be treated with respect with regard to their human rights, ethics, privacy and confidentiality, informed consent, autonomy and dignity.”[48] Furthermore, international guidelines on HIV urge states to take measures to ensure that consumer protection laws and other relevant legislation are “enacted or strengthened to prevent fraudulent claims regarding the safety and efficacy of drugs, vaccines and medical devices, including those relating to HIV.”[49] PATP did not comply with any of these standards, trampling on patient autonomy and confidentiality through its public disclosure of patients’ private health records and resulting in a decline in their already fragile health status by ordering them to stop their antiretroviral medications.[50] The cessation of antiretroviral treatment can lead to serious adverse effects, including death—which sadly occurred in The Gambia. It can also lead to HIV drug resistance.[51]

PATP inflicted cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment on patients and was an unnecessary medical intervention. Such treatment is prohibited by various regional and international human rights instruments, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[52] As argued by the UN Special Rapporteur on torture, medical care that negligently or intentionally causes severe suffering for no justifiable reason can be considered to constitute cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.[53] The poor quality of care in PATP caused physical suffering, with many patients falling sick with opportunistic infections such as tuberculosis.[54] The program’s poor-quality care was “both dehumanizing and damaging to their already fragile health status.”[55] According to the World Health Organization, health systems providing services to people living with HIV must include the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections such as tuberculosis and the delivery of antiretroviral medications.[56]

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights has described cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment as including actions that cause serious psychological suffering and humiliation.[57] PATP’s treatment regimen dehumanized people living with HIV by invading their privacy, for it involved sexualized treatment procedures that included touching and massaging private body parts.[58] Jammeh personally slathered and massaged the half-naked bodies of his patients with a mysterious concoction, including over the bare breasts of women living with HIV.[59] The treatment sessions were filmed and subsequently broadcast on the Gambia Radio Television Services, violating patients’ confidentiality and disclosure rights. Unauthorized disclosure of HIV status is a frequent abuse against people living with HIV across the globe and can cause severe mental anguish for these individuals.[60]

A former PATP enrollee* reported feeling compelled to join the program because of Jammeh’s persona as a dictator.[61] Once enrolled, curtailment of their freedom of movement amounted to false imprisonment, with patients reporting that they felt they could not freely leave PATP. Treatment sessions were conducted under the watch of soldiers who also closely guarded and watched patients.[62] Patient autonomy and informed consent were ignored, with patients feeling they could not decline or question treatment procedures.[63]

Moreover, violations continued once patients were discharged from the program. Many of them tried to return to conventional health care to be reinstated on antiretroviral medications but were denied access to services. Such patients thus suffered additional discrimination from health care workers, who labeled them “defaulters” and prioritized patients who had not tried the PATP cure. One health care worker admitted that she stopped accepting patients who had received the PATP cure after 10 of them died in her care in a span of three months.[64]

The international community’s response to Jammeh’s health dictatorship through PATP was mixed. Some international HIV experts spoke out strongly against Jammeh and PATP. For example, the HIV Medicine Association castigated Jammeh for giving false hope to people living with HIV and for recklessly experimenting with people’s lives.[65] Hoosen Coovadia, head of HIV research at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, stated, “For a country’s leader to come up with such an outlandish conclusion is not only irresponsible, but also very dangerous, and he should be reprimanded and stopped from proclaiming such nonsense.”[66]

The World Health Organization and UNAIDS issued a statement that did not directly reprimand PATP or Jammeh’s actions, instead reiterating that there was no cure for AIDS and encouraging Jammeh to scientifically examine the safety and efficacy of his treatment.[67] The statement was issued on March 16, 2007, three months after PATP’s rollout and roughly a month after Gwaradzimba was expelled from The Gambia. It read in part, “Herbal remedies cannot take the place of comprehensive treatment and care for people living with HIV (including prophylaxis and treatment for opportunistic infections, and highly active antiretroviral therapy where indicated). These treatments should not be stopped in favor of any such remedy.”[68] Antonio Filipe Jr., head of the World Health Organization in Senegal, stated, “As the World Health Organization, we would like to state quite clearly the following … so far there is no cure for AIDS,” adding that the organization “respects the president’s point of view.”[69] These statements were mild and diplomatic and failed to strongly call out Jammeh’s actions as a violation of the right to health of people living with HIV.

Without strong and persistent opposition, PATP continued for 10 years, and people living with HIV suffered harm while the world—including the UN and World Health Organization—watched. Arguably, the UN’s act of replacing Gwaradzimba (who had openly criticized PATP) and then not placing any further pressure on Jammeh meant that it had resolved to turn a blind eye to the violations being perpetrated on people living with HIV.[70] Even when the Special Rapporteur on torture visited The Gambia in 2015, he did not investigate PATP or the PATP cure—neither was mentioned in his report on human rights issues in the country.[71]

Unfortunately, The Gambia is but one of many instances in which a fraudulent HIV cure or unscientifically sound HIV theory has been promoted by state officials or adopted as official government policy.[72] Historically, the responses of the UN and the World Health Organization have been consistent—diplomatic statements are issued, with no follow-up actions or attempts to protect people living with HIV. When HIV denialism and an attack on access to antiretroviral treatment was spearheaded first by South Africa’s health minister and then by deputy president Thabo Mbeki as an official state policy, the UN merely issued press releases, doing nothing more to counter the propaganda.[73] And in 2007, when Iran announced the immune-modulator drug as an HIV cure and tested it on people living with HIV without their informed consent or an independent ethical review, UNAIDS and the World Health Organization did not even issue a statement.[74] In public remarks, the United Nations Children’s Fund’s coordinator on HIV in Iran at the time said nothing about the drug, instead praising Iran’s efforts to fight HIV.[75]

The UN and World Health Organization must do more to address fraudulent HIV cures beyond issuing press releases and statements. Advocacy campaigns are one option that these organizations have used to address challenges affecting the rights of people living with HIV. For example, both entities vigorously championed global efforts aimed at ending the criminalization of HIV transmission. To achieve this goal, they generated expert research and guidelines on the harmful impacts of such criminalization and launched and supported a global campaign urging nations to abolish laws that fuel rather than help control and manage HIV.[76] That same vigor should have been used to address the dire situation in The Gambia and should be used now to deal with constantly emerging fraudulent HIV cures that are promoted by powerful political figures or that are part of official state policy.

The World Health Organization has infrastructure and measures in place to deal with counterfeit medicines, but these approaches do not address herbal HIV cures supported by a health dictatorship. Since 1988, it has sought to ensure that governments and pharmaceutical manufacturers cooperate “in the detection and prevention of the increasing incidence of the export or smuggling of falsely labelled, counterfeited or substandard pharmaceutical preparations.”[77] The International Medical Products Anti-Counterfeiting Taskforce (IMPACT) was launched to deal with counterfeit drugs in 2006. IMPACT is made up of national regulators, pharmaceutical companies, nongovernmental organizations, and INTERPOL, among others.[78] Although IMPACT assists states in dealing with counterfeit drugs, it has not designed an approach for dealing with health dictatorships that result in the use of untested herbal medicines or cures.

Similarly, the World Health Organization’s traditional medicine strategy, which seeks to regulate the development of traditional medicines, makes no mention of how to deal with fraudulent traditional medicines promoted from the highest levels of political office.[79] The strategy promises to “facilitate information sharing and international regulatory network development.” An international regulatory framework should address the current gap with respect to health dictatorships.

The Global Surveillance and Monitoring System for Substandard and Falsified Medical Products is an entity of the World Health Organization focused on monitoring and sharing information on counterfeit medicines and medical products in conventional health settings.[80] It has been publishing reports and issuing drug alerts on counterfeit conventional medicines since 1989 but has never issued a drug alert with respect to PATP or Iran’s immune-modulator drug.[81] This is despite the widespread and long-term use of PATP in The Gambia, as well as the reported introduction of the immune-modulator drug beyond Iran’s borders into Zimbabwe. In 2013, six years after the drug’s rollout in Iran, the Zimbabwean government reportedly added it to the available treatment regimen for HIV positive people in Zimbabwe, despite substandard and unethical testing procedures for the product.[82]

Addressing fraudulent HIV cures globally conforms to UNAIDS’ mandate of promoting a human rights-based approach to HIV in order to “create an enabling environment for successful HIV responses and affirm the dignity of people living with, or vulnerable to, HIV.”[83] Based on this self-proclaimed goal, UNAIDS needs to work with the World Health Organization to monitor fraudulent HIV cures and their promotion, to develop global standards and guidelines to protect people living with HIV, and to provide advocacy tools for those affected.

Conclusion

PATP broke Gambian national laws and violated international human rights law by subjecting people living with HIV to cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, infringing on their right to health, and flouting international standards of care for people living with HIV. The program also made it difficult for health care workers to effectively deliver health and counseling services to their patients.

The UN and World Health Organization can and should do more to consistently speak out and take action against any purported HIV cures that are distributed to people living with HIV without the backing of rigorous testing procedures that confirm their safety and efficacy. The voice and actions of these international global health actors is necessary to give direction to state policies and protect the human rights of people living with HIV.

Through the Global Surveillance and Monitoring System for Substandard and Falsified Medical Products and IMPACT, the infrastructure and models already exist to monitor and minimize the distribution of conventional counterfeit medicines, and UNAIDS and the World Health Organization should consider adapting these mechanisms to include monitoring fraudulent herbal HIV cures.

Alternatively, UNAIDS and the World Health Organization could consider the creation of a global task force to monitor and provide information on fraudulent cures for HIV and other diseases, including herbal medicines, particularly those that are promoted by governments or political figures. Such an entity could be a global authoritative voice on the efficacy of so-called cures and could work to ensure that governments follow widely accepted protocols in the creation, testing, and rollout of any new drugs in order to avoid causing highly vulnerable people to abandon their life-saving antiretroviral treatments. The task force could also carry out research that measures the impact of fraudulent HIV cures on the fight against HIV and AIDS and documents loss of life due to these harmful initiatives. Currently, deaths resulting from the promotion of fraudulent HIV cures is missing from global statistics on HIV-related deaths. This kind of research is critical for policy formulation at the regional and local levels, as well as for the protection of the rights to life and health of people living with HIV.

Jammeh is not the first head of state to use his power and position to shape access to care and the management of HIV and AIDS, nor will he be the last. According to a Harvard study, former South African president Thabo Mbeki’s AIDS denialism in the 1990s caused 300,000 deaths. When people living with HIV and AIDS are victims of state policies that wipe them out by the hundreds and thousands, that is a gross human rights violation. Where fraudulent HIV cures and limited access to antiretroviral medications are championed by those in power, there is a need for enhanced protection of the right to health through international and national protection mechanisms in light of the influence and sway that political leaders have over citizens. The next fraudulent HIV cure promoted by a powerful individual will certainly come, but is the international global health community ready to stand in defense of people living with HIV?

Sarah L. Bosha, LLBS, LLM, is an assistant teaching professor of global health and human rights at the Eck Institute for Global Health, University of Notre Dame, and a legal and research associate at AIDS-Free World, USA.

Michelle Adeniyi, BA, MSGH, is a graduate of the Masters in Global Health program at the Eck Institute for Global Health, University of Notre Dame, USA.

Jenna Ivan, BA, MSGH, is a graduate of the Masters in Global Health program at the Eck Institute for Global Health, University of Notre Dame, USA.

Roya Ghiaseddin is a professor at the Department of Applied and Computational Mathematics and the Eck Institute for Global Health, University of Notre Dame, USA.

Fabakary Minteh, HND, BSc, is a graduate assistant in the Department of Public and Environmental Health, School of Medicine and Allied Health Sciences, University of The Gambia.

Lamin F. Barrow, HND, BSc, is a graduate assistant in the Department of Public and Environmental Health, School of Medicine and Allied Health Sciences, University of The Gambia.

Rex Kuye, MSc, MPH, PhD, FWAPCEH, is an associate professor and head of the Department of Public and Environmental Health, School of Medicine and Allied Health Sciences, University of The Gambia.

Competing interests: None declared.

Please address correspondence to Sarah L. Bosha. Email: sbosha@nd.edu.

Copyright © 2019 Bosha, Adeniyi, Ivan, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

*Changes were made to the text after publication on 8 October 2019

References

[1]. J. Amon, “Dangerous medicines: Unproven AIDS cures and counterfeit antiretroviral drugs,” Globalization and Health (February 2008). Available at https://globalizationandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1744-8603-4-5.

[2]. “Gambia’s President claims he has a cure for AIDS,” NBC News (February 2007). Available at http://www.nbcnews.com/id/17244005/ns/health-aids/t/gambias-president-claims-he-has-cure-aids/#.W84uY_ZFw2w.

[3]. Ibid.

[4]. “Gambia crisis ends as Yahya Jammeh leaves for exile,” Al Jazeera (January 22, 2017). Available at https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/01/jammeh-arrives-banjul-airport-stepping-170121210246506.html.

[5]. Marco Evers, “The quack in Gambia, African despot ‘cures’ AIDS,” (March 8, 2007). Available at http://www.spiegel.de/international/spiegel/the-quack-in-gambia-african-despot-cures-aids-a-470231.html.

[6]. A. Serrano, “Gambia’s AIDS “cure” causes alarm,” CBS News (2007). Available at https://www.cbsnews.com/news/gambias-aids-cure-causes-alarm.

[7]. “Gambia’s President claims he has cure for AIDS” (see note 2).

[8]. N. M’Bai, Gambia: The untold dictator Yahya Jammeh’s story (2012).

[9]. UNAIDS, Trend of HIV infections (2018). Available at http://aidsinfo.unaids.org.

[10]. United Nations Population Fund, The state of world population 2018 (New York: United Nations Population Fund, 2018), p. 149.

[11]. Amon (see note 1).

[12]. R. Cassidy and M. Leach, “Science, politics and the presidential AIDS cure,” African Affairs 108/433 (2009), p. 559.

[13]. See Presidential Alternative Treatment Program. Available at http://qanet.gm/statehouse/patp.htm.

[14]. C. Petesch, “Gambians file suit against ex-leader over alleged HIV ‘cure’” (2018). Available at https://aidsfreeworld.org/latest-news-1/2018/5/31/ap-gambians-file-suit-against-ex-leader-over-alleged-hiv-cure.

[15]. “As Gambia celebrates ‘breakthrough in HIV/AIDS cure’, dictator Jammeh accuses Western pharmaceutical companies of conspiracy theory!,” Freedom Newspaper (January 19, 2016). Available at https://www.freedomnewspaper.com/2016/01/19/6641-2.

[16]. Cassidy and Leach (see note 12), p. 559.

[17]. Ibid., p. 571.

[18]. M. Darboe, “Playbook of a tyrant,” Torch (April 4, 2018). Available at https://torchongambia.wordpress.com/2018/04/04/jammehs-hiv-treatment-was-a-success-dr-mbowe.

[19]. “President’s herbal HIV/AIDS ‘cure’ boosts ARV use,” IRIN (November 3, 2008). Available at https://www.irinnews.org/fr/node/243786.

[20]. Ibid.

[21]. R. Becker, “Gambian president’s plans for hospital based on bogus claims of AIDS ‘cure’,” Africa Check (January 29, 2013). Available at https://africacheck.org/reports/gambian-presidents-plans-for-hospital-based-on-bogus-claims-of-aids-cure.

[22]. UN Resident Coordinator’s Office, UN System position with regards to AIDS treatment in The Gambia (The Gambia: United Nations, 2007), Available at https://africacheck.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/UN-System-Position-with-regards-to-AIDS-Treatment-in-the-Gambia-2007.pdf.

[23]. “Gambia expels UN AIDS official for ‘cure’ criticisms,” Reuters (February 23, 2007). Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-gambia-aids-un-s/gambia-expels-un-official-for-aids-cure-criticism-idUSL2343601120070223.

[24]. Cassidy and Leach (see note 12), p. 560.

[25]. P. Tsikata, G. Pindi, and A. Anaele, “The frozen rhetoric of AIDS denialism and the flourishing claims of a cure: A Comparative analysis of Thabo Mbeki and Yahya Jammeh’s rhetoric,” Communication 42/3 (2016), pp. 378–397.

[26]. “Gambia crisis ends as Yahya Jammeh leaves for exile” (see note 4).

[27]. M. Patton, Qualitative research and evaluation methods (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2015).

[28]. Ibid.

[29]. Ibid.

[30]. Global HIV Strategic Information Working Group, Biobehavioural survey guidelines for populations at risk for HIV (2017). Available at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/258924/1/9789241513012-eng.pdf?ua=1.

[31]. C. Freeman, “The president who made people take his bogus HIV cure,” BBC News (2018). Available at https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-42754150.

[32]. Petesch (see note 14).

[33]. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI) (1966), art. 12(1).

[34]. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000), para. 8; see also para. 12(b).

[35]. Ibid, para, 12 (d), (e).

[36]. G. Ndow, M. Gore, Y. Shimakawa, et al., “Hepatitis B testing and treatment in HIV patients in The Gambia: Compliance with international guidelines and clinical outcomes,” PLoS One 12/6 (2017), p. 8.

[37]. The Gambia Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, Health policy framework (January 2006). Available http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—ilo_aids/documents/legaldocument/wcms_126701.pdf; see also Republic of The Gambia, HIV and AIDS Prevention and Control Act 2015.

[38]. The Gambia Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (see note 37), p. 19; see also Republic of The Gambia, HIV and AIDS Prevention and Control Act 2015.

[39]. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see note 34), para. 12(b).

[40]. See J. E. Méndez, Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment: Mission to the Gambia, UN Doc. A/HRC/28/68/Add.4 (2015).

[41]. “Gambia’s UN envoy ‘is expelled’,” BBC News (2007). Available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/6390319.stm.

[42]. S. Stonbraker, M. Befus, L. Nadal, et al., “Factors associated with health information seeking, processing, and use among HIV positive adults in the Dominican Republic,” AIDS Behavior 21/6 (2017), pp. 1588–1600.

[43]. T. Veinot, “Interactive acquisition and sharing: Understanding the dynamics of HIV/AIDS information networks,” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60/11 (2009), pp. 2313–2332.

[44]. A. Kotze and M. L. Jaiteh, “‘No sex, no coffee, no ARVs’: Former president’s quackery could land him in court,” Bhekisisa Center for Health Journalism (April 24, 2018). Available at https://bhekisisa.org/article/2018-04-24-00-a-legacy-of-lies-gambians-seek-justice-for-former-presidents-bogus-aids-cure.

[45]. “President’s herbal HIV/AIDS ‘cure’ boosts ARV use” (see note 19).

[46]. Ibid.

[47]. Ibid.

[48]. World Health Organization, Standards for quality HIV care: A tool for quality assessment, improvement and accreditation (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004), p. 8.

[49]. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and UNAIDS, International guidelines on HIV/AIDS and human rights (Geneva: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and UNAIDS, 2006), para. 37.

[50]. See International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI) (1966), art. 12.

[51]. UNAIDS and World Health Organization, “UNAIDS and WHO underline importance of evidence based approaches to treatment in response to AIDS,” press release (March 16, 2007). Available at http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/web_story/070316_gambia_statement_en_0.pdf.

[52]. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI) (1966), art. 7.

[53]. J. E. Méndez, Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, UN Doc. A/HRC/22/53 (2013), p. 9.

[54]. “President’s herbal HIV/AIDS ‘cure’ boosts ARV use, IRIN News, November 3, 2008. Available at https://www.irinnews.org/fr/node/243786.

[55]. Méndez (2013, see note 53), p. 17.

[56]. World Health Organization (2004, see note 48).

[57]. Ibid.

[58]. “Survivors of Yahya Jammeh’s bogus AIDS cure sue former Gambian leader,” Guardian (June 1, 2018). Available at https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/jun/01/survivors-yahya-jammehs-bogus-aids-cure-sue-former-gambian-leader.

[59]. The Breakthrough: Part I. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eADHnTdrMGo. See also The Breakthrough: Part II. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vNPzS2P8MGw.

[60]. Méndez (2013, see note 53), p. 17.

[61]. Interview Fatou Jatta. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P_gkKa1G69Q&t=20s.

[62]. Kotze and Jaiteh (see note 44).

[63]. See M. Adeniyi, Perceptions of the Presidential Alternative Treatment Program among PLHIV in The Gambia, master’s thesis (2018).

[64]. See J. Ivan, The effect of the Presidential Alternative Treatment program on health services for PLHIV and HIV policy in The Gambia, master’s thesis (2018).

[65]. Infectious Diseases Society of America, “HIV experts oppose Gambia’s unproven AIDS remedy,” Science Daily (May 3, 2007). Available at https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/04/070430155808.htm.

[66]. J. Koinange, “In Gambia, AIDS cure or false hope?,” CNN (March 17, 2017). Available at http://edition.cnn.com/2007/WORLD/africa/03/15/koinange.africa.

[67]. Amon (see note 1).

[68]. UNAIDS and World Health Organization (see note 51).

[69]. Serrano (see note 6).

[70]. “UNDP names new chief envoy for Gambia after former envoy expelled for questioning President Jammeh’s claims of cure for HIV/AIDS,” Kaiser Health News (2007). Available at https://khn.org/morning-breakout/dr00044229.

[71]. Méndez (see note 40).

[72]. Amon (see note 1), p. 2.

[73]. Ibid, p. 4.

[74]. “Iran introduces new AIDS treatment,” Mehr News (February 3, 2007). Available at https://en.mehrnews.com/news/22098/Iran-introduces-new-AIDS-treatment.

[75]. Amon (see note 1), p. 3.

[76]. See UNAIDS, Ending overly broad criminalization of HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission: Critical scientific, medical and legal considerations. Available at http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20130530_Guidance_Ending_Criminalisation_0.pdf. See also World Health Organization, “Sexual health, human rights and the law.” Available at http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/sexual_health/sexual-health-human-rights-law/en.

[77]. World Health Organization, IMPACT frequently asked questions and answers, p. 1. Available at https://www.who.int/medicines/services/counterfeit/impact-faqwa.pdf.

[78]. Ibid., p. 3.

[79]. World Health Organization, WHO traditional medicine strategy (2013). Available at https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/traditional/trm_strategy14_23/en.

[80]. World Health Organization, WHO global surveillance and monitoring system for substandard and falsified medical products (2017), p. 5. Available at https://www.who.int/medicines/regulation/ssffc/publications/gsms-report-sf/en.

[81]. World Health Organization, Full list of WHO medical products alerts. Available at https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/drugalerts/en.

[82]. T. Ndlovu, “New ARVs deal for Zimbabwe,” Herald (2013). Available at https://www.herald.co.zw/new-arvs-deal-for-zim.

[83]. UNAIDS, Human rights. Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/topic/rights.