Athena K. Ramos

Abstract

Tobacco production is a multi-billion-dollar global industry. Unfortunately, the cultivation of tobacco engages the labor of children throughout the world in extremely dangerous environments, which has both immediate and long-term consequences for children and society. This paper explores the human rights concerns associated with child labor in tobacco production by highlighting three countries—the United States, Kazakhstan, and Malawi—and examines the impact that the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, and the ILO’s Safety and Health in Agriculture Convention have on child labor practices in tobacco production. It also proposes general actions to address the human rights concerns related to child labor practices in tobacco production, as well as specific actions for selected countries. A human rights-based approach to reducing child labor in agriculture could create meaningful changes that improve lives and opportunities for health, education, and economic stability among children and families across the globe.

Introduction

The tobacco industry is a multi-billion-dollar business.1 It is dominated by large multinational companies, including Phillip Morris International, British American Tobacco, Japan Tobacco International, Altria (formally known as Phillip Morris USA), the China National Tobacco Corporation, and the Imperial Tobacco Group, which together posted profits exceeding US$62 billion in 2015.2

Tobacco production and consumption are public health issues with human rights implications.3 Global tobacco giants, through a complex supply system, engage the labor of children throughout the world in extremely dangerous environments, which has both immediate and long-term consequences for the children being employed and for society. This paper explores the human rights concerns associated with child labor in tobacco production by reviewing three countries—the United States, Kazakhstan, and Malawi—which were chosen as examples that highlight different levels of human and economic development. It also examines the impact that the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention (C-182), and the ILO’s Safety and Health in Agriculture Convention (C-184) have on child labor practices in tobacco production. It concludes by proposing actions to address the human rights concerns related to child labor practices in tobacco production. Although this article focuses specifically on child labor in tobacco production, the human rights-based solutions discussed have crosscutting implications for child labor throughout the agricultural industry.

Agricultural industry

Agriculture is one of the few industries that exempts some employers from mandates to provide safe working environments for employees in the United States and across the globe.4 There are substantially fewer protections for those working in agriculture than in other industries. Research has shown that agriculture is one of the most dangerous industries in the world.5 Within the United States, the agricultural industry has the second-highest fatality rate among young workers.6 Nearly half of the total occupational fatalities among children occur in agriculture.7

Child labor in agriculture

International law defines a child as a person under the age of 18, unless the age of majority is attained earlier under the law.8 Child labor is “work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential, and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development.”9 Globally, about 152 million children are involved in child labor and 73 million children are involved in hazardous work.10 Across the world, more children work in agriculture than in any other sector of the economy, and the majority of full-time working children are in the commercial agriculture sector.11

Child labor remains relatively unaddressed within the agricultural industry and is the product of the triangulation of employers, parents, governments, and an overarching international and national legal structure that allows such practices to exist.12 Child labor is profitable. In some cases, parents employed in low-wage agricultural jobs may be forced to have their children work because child care is unavailable or too costly. In other cases, parents may need their children to work in order to help support the family. Some governments allow child labor in order to promote investment or stabilize the national economy. Further, international actors such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund continue to influence social and economic policies, which may inadvertently result in weak national legal structures and poor enforcement of labor laws, especially those protecting children. Finally, the tobacco industry and its allies have effectively lobbied, at multiple levels, against policies and regulations that protect workers.13

Tobacco production: A commodity market

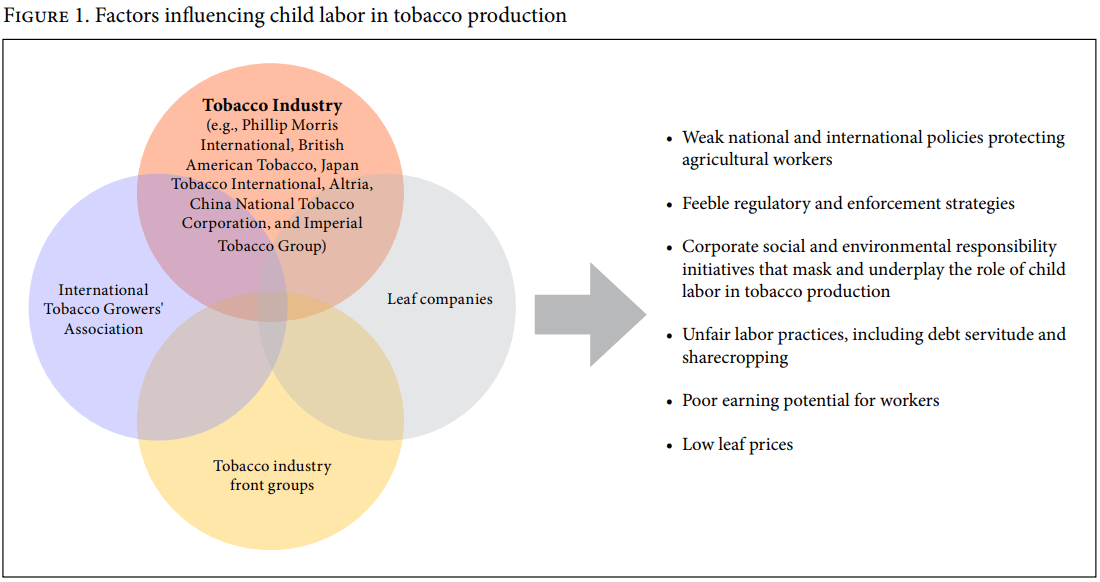

Tobacco is an agricultural commodity product. Up until the 1960s, the United States dominated global tobacco production; however, now China, Brazil, and India lead the United States.14 Much of US tobacco production has been outsourced to the developing world.15 In fact, tobacco is now produced in 125 countries, including Argentina, Guatemala, Indonesia, Italy, Kenya, Pakistan, Poland, Thailand, Turkey, and Zimbabwe.16 In a quest to lower production costs and increase shareholder value, multinational companies move into less regulated countries, where they negotiate extremely low prices that often result in debt servitude or the producers’ use of child labor. Sharecropping is also commonly used as a mechanism to gain access to cheaper labor and to transfer the risk from landowners to workers.17 Tobacco companies benefit from these unfair labor practices.18 Figure 1 highlights the confluence of factors that influence child labor in tobacco production. The circles in the figure overlap to signify the collusion between the tobacco industry and their front groups, leaf companies, and the International Tobacco Growers’ Association.

There are several reasons for the lack of accurate data on the number of children working in tobacco production. These include children working as unpaid family members, underreporting, and a lack of labor law enforcement. Additional research is needed to more precisely estimate the number of child farmworkers in tobacco production across the world.

Tobacco production

Dangerous health consequences

Tobacco production is a dangerous endeavor for adults, and even more so for children. Children working on tobacco farms may face a variety of hazardous exposures, including long hours, lacerations and piercings from equipment, chemicals, heavy lifting, climbing, and extreme weather conditions.19 They may also lack access to water, appropriate nutrition, and sanitation facilities.20 Children are especially vulnerable to the impacts of these exposures because of their physical stage of development. An immediate health risk to children working on tobacco farms is green tobacco sickness. This sickness is an occupational illness caused by dermal absorption of nicotine from the leaves of the tobacco plant.21 It is a form of nicotine poisoning and is exacerbated by working in wet or damp environments.22 Numerous reports have highlighted stories of farmworkers, both children and adults, who have experienced the illness. A recent study of farmworkers in North Carolina found that tobacco farmworkers had higher levels of cotinine (a nicotine metabolite) than actual smokers.23 Green tobacco sickness can have serious and acute implications, such as dizziness, headaches, nausea, vomiting, dehydration, anorexia, and insomnia. Adding to the dangers of the illness, the application of and exposure to chemicals such as pesticides, herbicides, fumigants, and growth inhibitors without the use of appropriate personal protective equipment may increase risk. Children who work on tobacco farms may face serious chronic health consequences, including a higher risk of cancer, reproductive health issues, mood disorders, and permanent neurological damage.24

Child labor in the United States

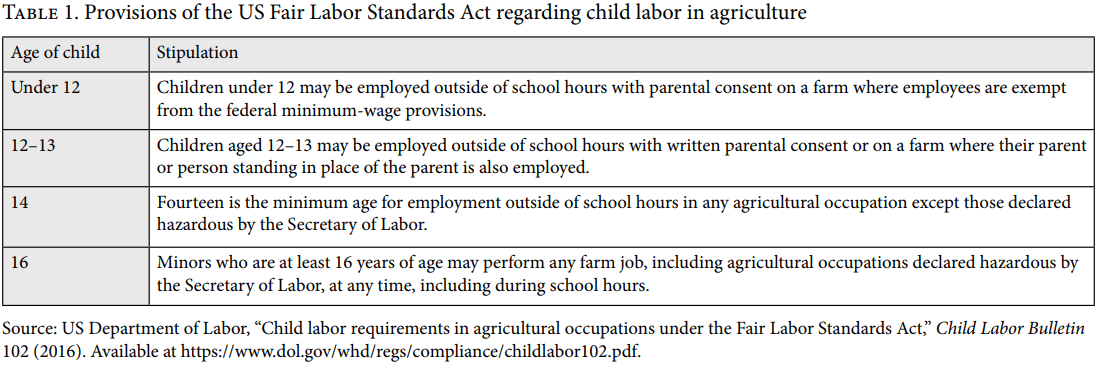

There are still thousands of children in the United States (mainly in Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia) working in tobacco fields.25 Although child labor in agriculture is a hotly debated topic, the fact is that many labor laws do not equally protect children working in agriculture compared to other industries. This is an example of “agricultural exceptionalism.” According to US federal labor law, “A child of any age may be employed by his or her parent or person standing in place of the parent at any time in any occupation on a farm owned or operated by that parent or person standing in place of that parent.”26 Table 1 highlights the age restrictions on the employment of children in agriculture as part of the Fair Labor Standards Act. It is also important to note that federal child labor provisions do not require minors to obtain work permits and do not limit the number of hours or times of day (other than outside of school hours) that young farmworkers may legally work. Minimum-wage standards do not apply to all farmworkers, and workers under the age of 20 can be paid a mere US$4.25 per hour during their first consecutive 90 calendar days of employment with a particular employer. In essence, children as young as 12 can work unlimited hours on a tobacco farm and be paid less than other workers as long as it does not interfere with school and they have parental permission.27

Although the Fair Labor Standards Act identifies a number of “hazardous” tasks through the Hazardous Occupations Orders for Agricultural Employment (HO/As), tobacco production tasks are not included. In 1998, the National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine issued recommendations to increase the minimum age for hazardous work from 16 to 18 for all children, regardless of whether they are employed in agriculture, and to require compulsory compliance with the HO/As by all agricultural employers.28 Recently, there was a proposal to create a new HO/A to prohibit children from being involved in the production and curing of tobacco. Finally, in late 2014, a bill was introduced in Congress to prohibit children under 18 from working in tobacco fields; however, no changes in policy or regulations have ensued.29

In early 2015, the US Department of Labor released recommendations developed by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health that specified the personal protective equipment—such as long-sleeve shirts, long pants, gloves, and water-resistant clothing—that should be utilized when handling tobacco leaves; however, the document did not mention the use of child labor in the production process. It is clear that the US government is not adequately protecting child tobacco farmworkers nor upholding its responsibilities under various international standards.

Child labor in Kazakhstan

Over 25% of Kazakhstan’s population works in agriculture.30 A significant number of these workers, especially migrant children, are employed on tobacco farms. In 2006, children were thought to make up about 60% of the country’s tobacco workforce; however, no exact number of child tobacco farmworkers is currently available.31 Based on a study conducted in 2009, child labor on Phillip Morris International farms was found to be widespread, and many workers were paid by the piece.32 Moreover, most tobacco farmworkers were uninformed of the potential occupational risks or health consequences that they faced. Due to increasing pressure, Phillip Morris International contracted with a local nongovernmental organization, the Local Community Foundation, to directly handle farmworkers’ grievances and set up a hotline to receive complaints and provide supportive services.33

Although the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection restricts the employment of children under 18 in tobacco production and the Labor Code of Kazakhstan prohibits the employment of people under 18 in hazardous conditions, the employment of children on tobacco farms still occurs. A case documenting labor abuses was presented to the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 2010, and information on this issue was presented to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery in 2012.34 In 2014, the US Department of Labor declared that Kazakhstan had made a minimal advancement in efforts to eliminate the worst forms of child labor, such as that found in agriculture.35

Child labor in Malawi

According to Marty Otañez, Adeline Lambert, and Raphael Sandramu, “Malawi is the most tobacco-dependent country in the world.”36 In fact, tobacco accounts for more than half of the country’s exports.37 Most tobacco workers have no contract with their employers and make a mere US$1.25 per day.38 Tobacco workers are sometimes part of a repressive tenancy system, and those unable to repay their debts may face debt bondage.39 When the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to food visited Malawi in 2013, he noted that 78,000 child laborers were employed in plucking tobacco leaves.40 The Special Rapporteur also noted that collusion among global tobacco companies over leaf prices was a human rights issue.41 Further, in 2015, over 50% of children on tobacco estates were found to be involved in stitching tobacco leaves as unpaid family members.42 Between 2000 and 2010, child labor is estimated to have saved the tobacco industry in Malawi over US$10 million.43

The problem of child labor in tobacco production in Malawi is rampant and well known. In 2010, Malawi-produced tobacco was listed by the US Department of Labor as having been produced using child labor, and this practice continues today.44 In a recent study, 63% of children from tobacco-growing families were found to be involved in child labor.45 According to Malawi’s Employment Act of 2000, child labor refers to any economic activity that involves a child under 14 years old. Although the Constitution states that children under 16 are entitled to protection from hazardous work and the Employment Act sets the minimum age for hazardous labor at 18, these provisions are not enforced. While there is a formal mechanism for reporting child labor complaints, most child labor cases are resolved through out-of-court settlements and fines.46 Clearly, even though mechanisms to address child labor exist, real change in practice has been elusive. Many nongovernmental groups have urged Malawi’s Parliament to pass the Tenancy Labor Bill or abolish the tenancy labor system in an effort to improve employment and health conditions on tobacco farms. They have also advocated for the right to organize under the Tobacco and Allied Workers Union. To date, however, no such legislation has been passed.47

Tobacco industry response

Tobacco companies understand the need to address child labor concerns throughout their supply chain. Altria, British American Tobacco, China National Tobacco, Imperial Tobacco Group, Japan Tobacco Group, Lorillard, and Phillip Morris International all purchase tobacco through direct contracts with growers or through tobacco leaf supply companies.48 In 2010, Phillip Morris unveiled a new global agricultural labor policy to prohibit child labor and develop guidelines and requirements for farmers, growers, and suppliers.49 In 2014, Altria signed a global pledge to eliminate all forms of child labor in its worldwide supply chain as part of an initiative promoted by the Eliminating Child Labour in Tobacco Growing Foundation, a foundation created by British American Tobacco. More recently, in 2016, the Sustainable Tobacco Program, an industry-wide initiative, was unveiled to address tobacco crop production, environmental concerns, labor issues (including child labor), health and safety facilities, and supply chain governance; however, it is still too early to evaluate what impact this initiative will have.50

Unfortunately, these types of moves, although framed as corporate social responsibility, represent more of a public relations strategy than any real meaningful change in practice. For example, in 2014, Phillip Morris International noted that it would buy tobacco only from third-party leaf companies rather than from direct contracts with growers, which was promoted as way to increase accountability, oversight, and implementation of strict standards regarding child labor. However, this transferred responsibility for monitoring child labor from the tobacco companies to the leaf companies, while allowing the tobacco companies to reap the benefit of cheap leaf products and continue to escape culpability for the problem. By promoting these types of initiatives, tobacco companies stand to gain political support and weaken opposition, especially in low-income and middle-income countries, where there may be less external monitoring by civil society and where financial contributions from these companies may have a greater impact.51

Human rights conventions

Tobacco production labor practices have significant implications for human rights, specifically the right to equality, the right to health, and the rights of children. Child labor on tobacco farms must be framed as part of the human rights agenda. This section examines three international treaties to assess their positions on child labor and their effectiveness in eliminating the practice.

United Nations Convention on the Rights of a Child

With 196 parties, the CRC is the most universally ratified human rights convention in the world; the United States is the only country that has not ratified it.52 Although the United States has not ratified the CRC, it has signed it, thereby requiring the country to refrain from engaging in practices that undermine and defeat the objective and purpose of the convention.

The CRC defines a child as a person under the age of 18. Accordingly, children are in need of special care and protection. The CRC establishes that children should be able to enjoy the highest standard of health.53 Article 32 states that parties to the CRC are obligated to

[r]ecognize the right of the child to be protected from economic exploitation and from performing any work that is likely to be hazardous or to interfere with the child’s education, or to be harmful to the child’s health or physical, mental, spiritual, moral, or social development.54

Numerous studies have documented that children working on tobacco farms are exploited and work in hazardous conditions that may interfere with their health, education, and well-being. It is time for states parties to act to protect these children by passing effective national legislation to abolish child labor in tobacco production and ensure that all organizations and individuals within their boundaries do not violate the rights of children as outlined in the CRC, including the rights to health, education, and relaxation and play. Without such action, states parties are liable for the breach of human rights obligations under international law.

International Labour Organization’s Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention (C-182)

The ILO’s Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention prohibits children under the age of 18 from engaging in hazardous labor that is likely to harm their health, safety, or morals.55 While this convention prohibits hazardous child labor, it is up to each national government to define what constitutes “hazardous work.” Parties to C-182 are required to design and implement a national action plan on the elimination of child labor and to set up a mechanism to oversee, monitor, and report on its implementation.56 Nearly every country in the world, including the United States, has ratified this convention.57 Although the United States has ratified this convention, it has not passed any laws to formally protect child tobacco farmworkers, such as an age restriction for working in tobacco production. Other countries, such as India and Brazil, have ruled that children cannot work on tobacco farms.58 According to interviews conducted in Brazil by Human Rights Watch, farmworker families know and understand that children under 18 cannot work legally in the fields or the families will face penalties.59 Enforcement of these penalties is lacking, but the threat of enforcement has begun to change practices in Brazil, even if child labor has not been completely eliminated.60

International Labour Organization’s Safety and Health in Agriculture Convention (C-184)

The ILO’s Safety and Health in Agriculture Convention provides a series of guidelines to protect agricultural workers and directs countries to develop national policies to this end.61 Article 16 specifically addresses young workers and hazardous work:

The minimum age for assignment to work in agriculture which by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out is likely to harm the safety and health of young persons shall not be less than 18 years.62

In some cases, a person as young as 16 may work in agriculture if appropriate training is provided and their health and safety is fully protected. Only 16 countries have ratified C-184—and, not surprisingly, the three studied here (United States, Kazakhstan, and Malawi) are not among them.63 Recent research from the World Bank suggests that in countries where agriculture is a key economic activity, support for industry regulations and safety controls, such as C-184, may be weak.64

Proposed actions

When child labor in tobacco production is examined through a human rights lens, it is clearly wrong and violates the rights of children. Child farmworkers should not be treated as a mere means to financial gain. Employers are receiving a financial benefit from using child farmworkers; however, families and society are paying the price for these actions in terms of lost potential and negative health, social, and educational outcomes. All children deserve to be treated with dignity and respect. Current tobacco production processes pose a risk to workers’ health, especially the health of child farmworkers, and as a result it is a violation of international law for children to be working in these conditions. Child labor in tobacco production is an enduring global dilemma that needs to be resolved from a human rights perspective.

Governments have a responsibility to protect their citizens and fulfill their obligations under international human rights law, but politics and the tobacco industry’s lobbying efforts have had a large influence on tobacco control policy around the world. These efforts have allowed the tobacco industry to evade accountability for their actions. Even though human rights advocacy has been found to raise awareness, a comprehensive multisectoral strategy using a rights-based approach is needed to fully eliminate child labor. Below is a list of recommended actions grouped by sector.

International legal system

Utilize international treaty mechanisms. The United Nations Ad Hoc Interagency Task Force on Tobacco Control meets every two years and is supportive of a human rights-based approach to tobacco control.65 The human rights-based approach is based on a number of principles: universality, indivisibility, interdependence, participation and inclusion, equality and non-discrimination, and accountability.66 Such an approach requires cross-sector collaboration and multilevel strategies.67

A number of strategies could be used to address child labor through international law. At a minimum, current international treaty obligations should be enforced. There should also be a standardization of what constitutes “hazardous” work under C-182. Tobacco production should be listed as hazardous given the plethora of science that shows the serious health consequences—both acute and long term—of working with tobacco. Reporting on child labor in tobacco production should be integrated into the Universal Periodic Review process for countries reporting before the United Nations Human Rights Council. This process provides “the opportunity for each State to declare what actions they have taken to improve the human rights situations in their countries and to fulfil their human rights obligations.”68 In addition, increased civil society monitoring of child labor on tobacco farms and the incorporation of these results into shadow reports for the CRC and C-182 could help raise awareness of this issue. Indeed, tobacco control issues have already been included in shadow reports for the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women and the CRC.69 Many useful tools have also been developed to help civil society participate in human rights monitoring and reporting.

Exploring additional international legal advocacy mechanisms to increase awareness of and decrease the use of child labor in tobacco production could be beneficial. Richard Daynard, Rangita de Silva de Alwis, and Mark Gottlieb have suggested some examples of further advocacy, including (1) submitting NGO reports to treaty monitoring bodies; (2) discussing child labor issues at constructive dialogues and pre-session meetings of states parties as part of reporting processes; (3) petitioning treaty monitoring bodies to include tobacco labor practice recommendations in their concluding observations on state party reports; (4) advocating for a particular focus on child labor on tobacco farms by United Nations Special Procedures, especially the Special Rapporteur on the right to health and the Special Rapporteur on corporate social responsibility; and (5) collaborating to ensure joint human rights and health dialogues at both the World Health Assembly and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.70

Implement the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Full implementation of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, another one of the most widely embraced conventions, is obligatory. In force since 2005, the convention currently has 168 signatories and 181 parties. Of the world’s top four tobacco-producing nations, three—China, Brazil, and India—have ratified the convention, while the United States has not.71 Even though the convention does not explicitly address child labor, it does contain articles that could be clarified and expanded to formally address child labor within the supply chain. For example, article 17 calls for the promotion of economically viable alternatives for tobacco workers, growers, and individual sellers, and article 18 calls for protection of the environment and the health of people working in tobacco cultivation and manufacture. Both of these articles represent opportunities that could be leveraged to reduce child labor. A human rights-based approach could provide the necessary enforcement linkage between various human rights treaties and the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control since the latter does not provide for enforcement.72

International development community

Reduce dependence on tobacco. Fostering more awareness on the link between child labor, tobacco, and food security is necessary. Tobacco quickly depletes land’s productive potential.73 Helping farmers find alternative livelihoods through crop diversification and access to supportive social policies could help in the transition away from tobacco production. For example, accessible credit systems could be created for farmers so that they can afford to grow different crops, invest in appropriate equipment, and borrow at reasonable interest rates.

Reward education. Research has demonstrated that poverty is both a cause and a consequence of child labor across the world. Child labor creates and maintains the cycle of poverty.74 As a global society, we should change social norms on child labor so that the long-term economic and social benefits of education outweigh the short-term financial payment of work. Rewarding families that send their children to school rather than to work may provide an incentive for education, especially in low-income and middle-income countries. Children have the right to education, and primary education should be universal. Extra fees for uniforms, books, and supplies or a lack of transportation should not be impediments to youth being able to attend school. Collaborative solutions between international actors, national governments, educational districts, and other interested partners should explore how this could be achieved as part of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Governments

Create parity under labor law. There should be equitable protection under the law for all farmworkers. Children should never work in hazardous environments, and children working in agriculture should have the same protections as children working in other industries. Therefore, legal changes may be needed to address and remedy the inequities that currently exist under national labor laws.

Promote and monitor farmworkers’ health. States have a duty to protect and monitor the public’s health. Most farmworkers never receive any safety training, health education, or personal protective equipment to help reduce their exposure to the tobacco plant. Assuring that all tobacco farmworkers have access to free personal protective equipment and are trained in how to properly use it could mitigate some of the associated health risks. At a minimum, gloves and water-resistant clothing should be provided. Additionally, a system to monitor farmworkers’ health should be developed, especially in rural areas where there generally is less access to health care.75

Mainstream child labor into existing legal enforcement structures in all countries. Current national child labor laws should be enforced. Often, enforcement authorities are underfunded and lack appropriate resources to fully complete their responsibilities. Ensuring appropriate funding and staffing for these positions is imperative. Additionally, making child labor a mainstream issue globally would help increase awareness about child labor and promote enforcement.

Civil society

Support and strengthen farmworker labor organizing initiatives. Throughout history, labor unions have helped rebalance the power structures between employers and employees, especially within the agricultural industry. Unions such as the United Farm Workers and the Farm Labor Organizing Committee of the AFL-CIO have consistently fought for workers’ rights. Unions could be a powerful mechanism for reducing child labor by raising such issues as part of the hiring processes or through the grievance-arbitration procedures set forth in collective bargaining agreements. Already, several thousand tobacco workers in North Carolina have joined the Farm Labor Organizing Committee.76 This type of strategy could be especially powerful in the developing world in countries such as Malawi, where there is an active union organizing effort.

Educate farmworker families. Farmworker families often have limited access to education about children’s rights as well as the risks and dangers of child labor in tobacco production. Families have a right to information, and states and employers have a duty to provide this information, such as that related to the health and social risks of working in tobacco production.77

Litigate cases of exploitive child labor on tobacco farms. Litigation may decrease dangerous and inhumane child labor practices on tobacco farms. Attorneys and civil society organizations could provide litigation support to exposed children and families by filing claims of human rights abuses on tobacco farms before regional human rights courts.78

Collaborate with other civil society groups. Farmworkers represent one of the most marginalized populations in the world, and addressing the issues they face requires multisector collaboration. A human rights-based approach may help build partnerships to address these critical issues. Farmworker advocates could establish coalitions and collaborations with other civil society groups such as those that focus on marginalized populations—including children, women, and indigenous groups—in order to foster awareness of human rights and human rights abuses, as well as develop a joint agenda for action. Some ideas for collaborative action include an international media campaign highlighting “a day in the life of a child tobacco farmworker” or product-labeling certificates that demonstrate that no child labor was used to produce the product.79 These types of activities could increase awareness of the human rights abuses occurring within tobacco production.

Employers

Pay living wages. Workers have a right to fair employment and to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of themselves and their families. Workers should not be compensated merely at minimum wage, which in many places is barely enough to survive. Instead, they should be paid a “living wage” that allows them to earn enough to maintain a decent standard of living.

Provide written contracts. Most tobacco workers never receive a written contract and therefore may become victims of wage theft, debt bondage, or other negative outcomes. A written contract can provide mutual clarity to workers and employers on the roles and responsibilities of each party, on working conditions, and on payment information

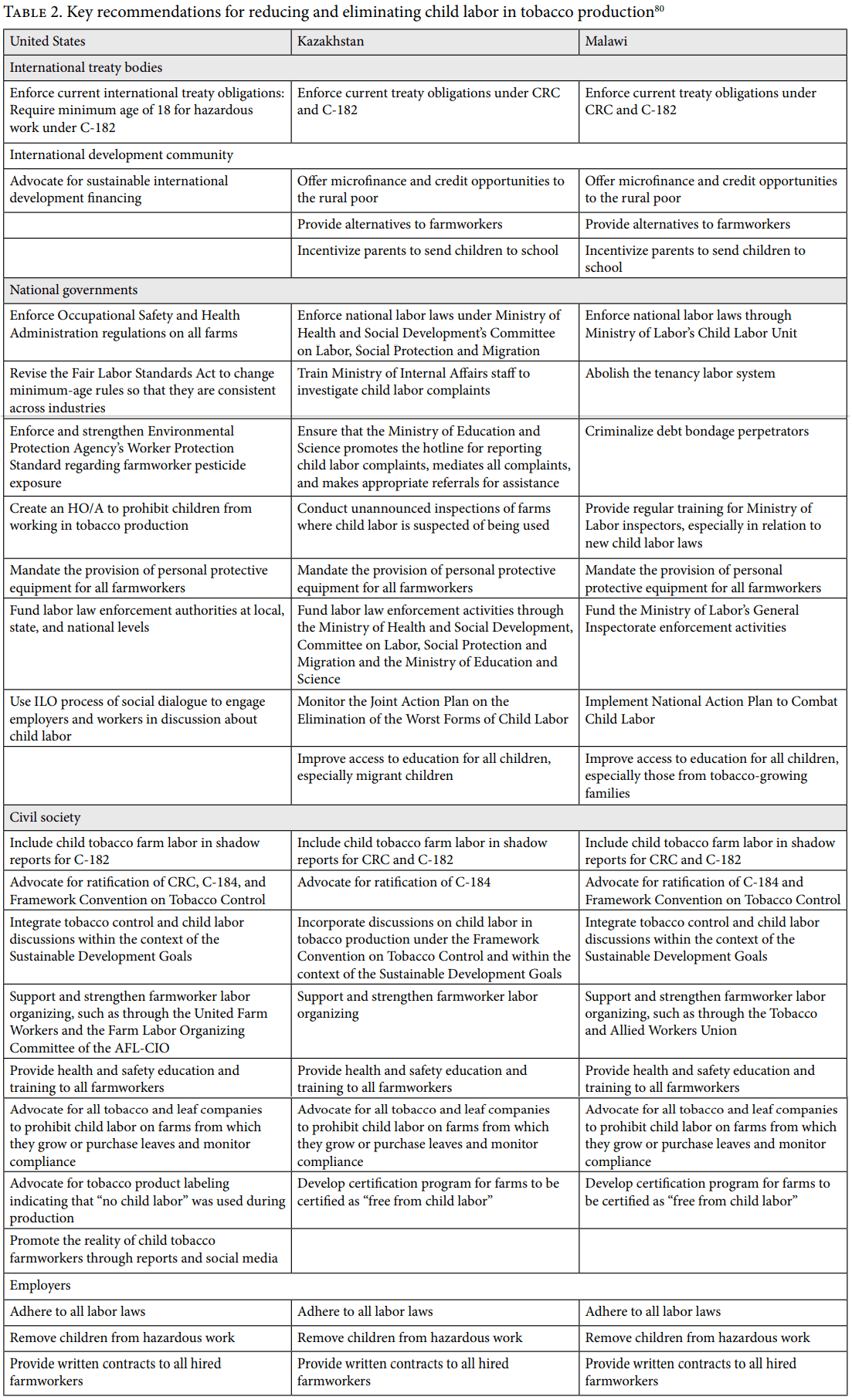

Specific recommendations are proposed in Table 2 for each of the three countries highlighted previously.

Child labor is a violation of children’s human rights. Responsible parties such as employers, parents, governments, and international and national actors should be held accountable for child labor in tobacco production. A comprehensive rights-based approach to reducing child labor in agriculture is needed to create meaningful changes that improve the lives and opportunities for health, education, and economic stability among children and families across the globe.

Farmworkers are an almost invisible population, hidden from the view of consumers and much of the world; however, they are essential to the global agricultural industry. In order to create a sustainable future, more attention must be paid to the plight of all farmworkers, especially children. Without this focus, this group of people will continue to be the invisible underclass, perpetuating the cycle of poverty. Farmworkers, although producing commodity products, are not and should not be considered commodities themselves. Upholding child tobacco farmworkers’ human rights is vital, and tolerating child exploitation in tobacco production is no longer an acceptable option.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Mark Small, Antonia Correa, and Natalia Trinidad for their early review of this manuscript.

Athena Ramos, PhD, MBA, MS, CPM, is an assistant professor in the Department of Health Promotion, Center for Reducing Health Disparities at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA, and a faculty fellow with the Rural Futures Institute at the University of Nebraska.

Please address correspondence Athena Ramos. Email: aramos@unmc.edu.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2018 Ramos. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- N. Lecours, G. E. G. Almeida, J. M. Abdallah, and T. E. Novotny, “Environmental health impacts of tobacco farming: A review of the literature,” Tobacco Control 21 (2012), pp. 191–196.

- Tobacco Atlas, Manufacturing (2018). Available at https://tobaccoatlas.org/topic/manufacturing.

- World Health Organization, Tobacco and the rights of the child (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001).

- SafeWork, International Labour Office, Safety and health in agriculture (Geneva: International Labour Office, 2000).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (June 2014). Available at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/aginjury.

- M. E. Miller, “Historical background of the child labor regulations: Strengths and limitations of the agricultural hazardous occupations orders,” Journal of Agromedicine 17 (2012), pp. 163–185.

- B. Marlenga, R. L. Berg, J. G. Linneman, et al., “Changing the child labor laws for agriculture: Impact on injury,” American Journal of Public Health 97/2 (2007), pp. 276–282.

- Convention on the Rights of the Child, G.A. Res. 44/25 (1989).

- International Labour Organization, What is child labour? (2015). Available at http://www.ilo.org/ipec/facts/lang–en/index.htm.

- International Labour Organization, Child labour. Available at https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/child-labour/lang–en/index.htmipec/documents/publication/wcms_221513.pdf.

- Z. F. Arat, “Child labor as a human rights issues: Its causes, aggravating policies, and alternative proposals,” Human Rights Quarterly 24/1 (2002), pp. 177–204.

- Ibid., p. 182.

- World Health Organization, Tobacco industry interference with tobacco control (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Tobacco production quantities by country, Average 1993–2013 (2015). Available at http://faostat3.fao.org.

- Lecours et al. (see note 1).

- World Health Organization, Growing tobacco (2016). Available at http://www.who.int/tobacco/en/atlas16.pdf.

- D. Lisboa Riquinho and E. Azevdo Hennington, “Health, environment, and working conditions in tobacco cultivation: A review of the literature,” Ciència e Saúde Coletiva 17/6 (2012), pp. 1587–1600.

- M. Otañez and S. A. Glantz, “Social responsibility in tobacco production? Tobacco companies’ use of green supply chains to obscure the real costs of tobacco farming,” Tobacco Control 20/6 (2011), pp. 403–411.

- Human Rights Watch, Tobacco’s hidden children: Hazardous child labor in the United States tobacco farming (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2014).

- N. Doytch, N. Thelen, and R. U. Mendoza, “The impact of FDI on child labor: Insights from an empirical analysis of sectoral FDI data and case studies,” Children and Youth Services Review 47 (2014), pp. 157–167.

- Lecours et al. (see note 1).

- T. A. Arcury, P. J. Laurienti, J. W. Talton, et al., “Urinary cotinine levels among Latino tobacco farmworkers in North Carolina compared to Latinos not employed in agriculture,” Nicotine and Tobacco Research (2015), pp. 1–9.

- Ibid.

- Human Rights Watch (2014, see note 19).

- Ibid.

- US Department of Labor, “Child labor requirements in agricultural occupations under the Fair Labor Standards Act,” Child Labor Bulletin 102 (2016). Available at https://www.dol.gov/whd/regs/compliance/childlabor102.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Marlenga et al. (see note 7).

- New York Times Editorial Board, “A ban on child labor in tobacco fields,” New York Times (December 28, 2014). Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/29/opinion/a-ban-on-child-labor-in-tobacco-fields.html?_r=0.

- United Nations Development Programme, 2015 Human development statistical tables. Available at http://hdr.undp.org/en/data.

- J. J. Amon, J. Buchanan, J. Cohen, and J. Kippenberg, “Child labor and environmental health: Government obligations and human rights,” International Journal of Pediatrics (2012), pp. 1–8.

- A. E. Kramer, “Philip Morris is said to benefit from child labor,” New York Times (July 14, 2010). Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/14/business/global/14smoke.html?_r=0.

- Phillip Morris International, Agricultural labor practices, progress report 2013 (2014). Available at https://www.pmi.com/resources/docs/default-source/pmi-sustainability/alp-progress-report-2013.pdf?sfvrsn=f402b0b5_0.

- Amon et al. (see note 31).

- US Department of Labor, Child labor and forced labor reports: Kazakhstan (2016). Available at https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/resources/reports/child-labor/kazakhstan.

- M. Otañez, A. Lambert, and R. Sandramu, “Reducing big tobacco’s control in agriculture” (2012). Available at http://www.laborrights.org/sites/default/files/publications-and-resources/Tobacco%20Position%20Paper.pdf.

- S. Baradaran and S. Barclay, “Fair trade and child labor,” Colombia Human Rights Law Review 43/1 (2011), pp. 1–63.

- “Research busts exploitation of tenants in Malawi tobacco estates: CFSC calls for labour law,” Nyasa Times (2015). Available at http://www.nyasatimes.com/2015/05/19/research-busts-exploitation-of-tenants-in-malawi-tobacco-estates-cfsc-calls-for-labour-law.

- US Department of Labor, Child labor and forced labor reports, Malawi (2016). Available at https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/resources/reports/child-labor/malawi.

- O. De Schutter, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right to food, UN Doc. A/HRC/25/57/Add.1 (2014).

- Unfair Tobacco, UN calls for tenancy labour bill in Malawi (2013). Available at https://www.unfairtobacco.org/en/meldungen/un-fordert-pachtarbeitsgesetz-in-malawi.

- “Research busts exploitation of tenants in Malawi tobacco estates: CFSC calls for labour law” (see note 38).

- M. C. Kulik, S. Aguinaga Bialous, S. Munthali, and W. Max, “Tobacco growing and the sustainable development goals, Malawi,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 95 (2017), pp. 362–367.

- Otañez and Glantz (see note 18); US Department of Labor (2016, see note 39).

- S. Boseley, “The children working the tobacco fields: ‘I wanted to be a nurse’,” Guardian (2018). Available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2018/jun/25/tobacco-industry-child-labour-malawi-special-report.

- This section draws extensively from US Department of Labor, Malawi (2016). Available at https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/resources/reports/child-labor/malawi.

- L. M’bwana, “CFSC caution on Malawi gvt’s readiness with tenancy bill for fear of empty promises,” Maravi Post (June 13, 2015). Available at http://www.maravipost.com/national/malawi-news/district/9021-cfsc-caution-on-malawi-gvt-s-readiness-with-tenancy-bill-for-fear-of-empty-promises.html.

- Human Rights Watch, S. tobacco giant’s move could reduce child labor (November 5, 2014). Available at https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/11/05/us-tobacco-giants-move-could-reduce-child-labor.

- Amon et al. (see note 31).

- British American Tobacco, Sustainable tobacco programme. Available at http://www.bat.com/srtp.

- This section draws extensively on Otañez and Glantz (see note 18).

- Convention on the Rights of the Child, G.A. Res. 44/25 (1989).

- Ibid, art 24.

- Ibid, art. 32.

- International Labour Organization, Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention (No. 182). (1999).

- Ibid.

- International Labour Organization, Ratifications of C182 – Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182). Available at http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:11300:0::NO:11300:P11300_INSTRUMENT_ID:312327.

- Human Rights Watch (2014, see note 19).

- M. Wurth, “Tobacco’s children: Brazil sets an example for the U.S.,” Progressive (November 3, 2015). Available at http://www.progressive.org/news/2015/11/188387/magazine-tobacco%E2%80%99s-children-brazil-sets-example-us.

- Ibid.

- International Labour Organization, Safety and Health in Agriculture Convention (No. 184) (2016).

- Ibid.

- International Labour Organization, Ratifications of C-184 – Safety and Health in Agriculture Convention, 2001 (No. 184). Available at http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:11300:0::NO:11300:P11300_INSTRUMENT_ID:312329.

- World Bank, Agribusiness rules lag in agriculture dependent countries (January 28, 2016). Available at http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2016/01/28/agribusiness-rules-lag-in-agriculture-dependent-countries.

- C. Dresler, H. Lando, N. Schneider, and H. Sehgal, “Human rights-based approach to tobacco control,” Tobacco Control 21 (2012), pp. 208–211.

- P. Hunt, A. E. Yamin, and F. Bustreo, “Making the case: What is the evidence of impact of applying human-rights based approaches to health?” Health and Human Rights Journal 2/17 (2015), pp. 1–9.

- R. Thomas, S. Kuruvilla, R. Hinton, et al., “Assessing the impact of a human rights-based approach across a spectrum of change for women’s, children’s, and adolescents’ health,” Health and Human Rights Journal 2/17 (2015), pp. 11–20.

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Universal Periodic Review (2015). Available at http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/UPR/Pages/UPRMain.aspx.

- R. A. Daynard, R. S. De Alwis, and M. Gottlieb, “International tobacco control: human rights-based approaches,” Public Health Advocacy Institute, Northeastern University School of Law (2009).

- Ibid.; Hunt et al. (see note 66).

- World Health Organization, Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (February 2015). Available at http://www.who.int/fctc/signatories_parties/en.

- Dresler et al. (see note 65).

- Daynard et al. (see note 69).

- K. Basu and Z. Tzannatos, “The global child labor problem: What do we know and what can we do?” World Bank Economic Review 17/2 (2003), pp. 147–173.

- Lisboa Riquinho and Azevdo Hennington (see note 17).

- Farm Labor Organizing Committee, Conditions in the fields. Available at http://www.floc.com/wordpress/reynolds-campaign/conditions-in-the-fields.

- A. K. Ramos, “A human rights-based approach to farmworker health: An overarching framework to address the social determinants of health.” Journal of Agromedicine 23/1 (2018), pp. 25–31.

- Daynard et al. (see note 69).

- Baradaran and Barclay (see note 37).

- US Department of Labor (2016, see note 35); US Department of Labor (2016, see note 39).