Nina Sun and Joseph J. Amon

Abstract

Twenty neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are currently recognized by the World Health Organization. They affect over one billion people globally and are responsible for significant morbidity, mortality, poverty, and social stigmatization. In May 2013, the World Health Assembly adopted a resolution calling on member states to intensify efforts to address NTDs, with the goal of reaching previously established targets for the elimination or eradication of 11 NTDs. The resolution also called for the integration of NTD efforts into primary health services. NTDs were subsequently included in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3, which calls for an end to the “epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and NTDs” by 2030. While both the World Health Assembly resolution and SDG 3 provide a strong framework for action, neither explicitly references the human right to the highest attainable standard of health or describes a rights-based approach to NTDs’ elimination. This article identifies key human rights relevant to NTD control and elimination efforts and describes rights-based interventions that address (1) inequity in access to preventive chemotherapy and morbidity management; (2) stigma and discrimination; and (3) patients’ rights and non-discrimination in health care settings. In addition, the article describes how human rights mechanisms at the global, regional, and national levels can help accelerate the response to NTDs and promote accountability for access to universal health care.

Introduction

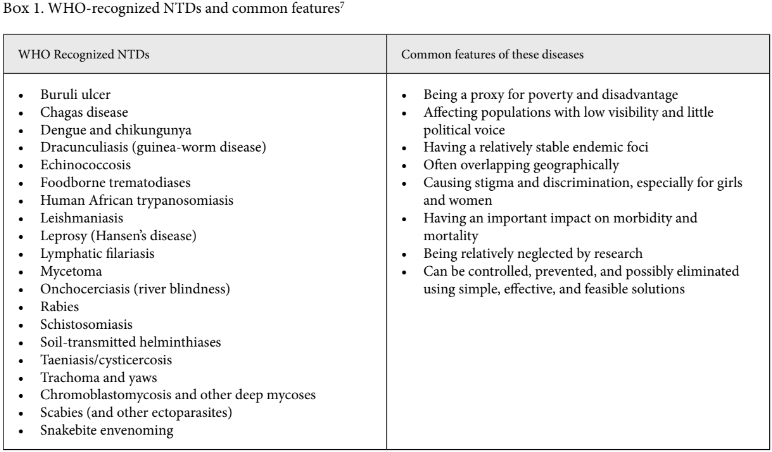

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes 20 “neglected tropical diseases” (NTDs).[1] These diseases share key common features, including disproportionately affecting poor communities and individuals with little social or political capital (see Box 1).[2]

While all 20 NTDs are preventable—and to varying degrees, treatable—they nonetheless affect over one billion people worldwide living in 149 countries and territories.[3] At least 100 countries are endemic for two or more diseases, and 30 countries are endemic for six or more.[4] NTDs also predominately affect those who are most disadvantaged—individuals living in low-income countries are most burdened with NTDs, and within those countries, the burden of NTDs is higher among poorer households. The people in these communities often live in inadequate housing, lack access to clean water and sanitation, and have little protection from insects and other disease vectors.[5]

NTDs are both a cause and a consequence of poverty, causing physical and intellectual impairments, preventing children from attending school, and reducing economic productivity.[7] They can also be severely stigmatizing: for example, lymphatic filariasis causes swelling (lymphedema) in 40 million people and, as with the deformations resulting from Buruli ulcer and yaws, can be socially exclusionary, often affecting individuals’ ability to work, to marry, and to care for and live with their families.[8] And fear of the disfiguring effects of leprosy and a centuries-long ignorance of the disease have resulted in individuals being shunned or exiled by their communities.[9]

Recognition of the underinvestment in the response to NTDs, relative to their significant health, economic, and social impacts, has led to increased global attention and commitment to their control and elimination. In May 2013, the World Health Assembly adopted a resolution calling on WHO member states to intensify efforts to address NTDs, with the goal of reaching previously established targets for the elimination or eradication of 11 NTDs. The resolution also called for the integration of NTD efforts into primary health services and universal access to preventive chemotherapy and treatment. NTDs were subsequently included in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3, adopted in September 2015, which calls for an end to the “epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and NTDs” by 2030.

Beyond setting disease-specific targets, the SDGs more generally seek to end health inequities and increase access to health care. Target 3.8, for example, calls on countries to “achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.” Goal 1, ending poverty in all its forms everywhere, highlights the importance of social protection systems for the most impoverished and marginalized. Reducing inequalities (goal 10) and ensuring access to clean water and sanitation (goal 6) are also prioritized. Action across all of these goals will facilitate the control and elimination of NTDs.

Identifying and addressing health inequities requires strong links to human rights. The WHO Constitution recognizes this, identifying the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health as a fundamental right of every human being.[10] However, health practitioners and policymakers often have little understanding of how to translate support for a right to health into rights-based interventions, and examinations of the links between human rights and NTDs have been limited to date.

Public health practitioners working for NTD control and elimination can benefit from understanding how to integrate human rights principles into their programs and how engagement with human rights mechanisms, such as special rapporteurs and expert committees related to international human rights treaties, can complement the medical and clinical aspects of their interventions. Therefore, this paper seeks to (1) briefly describe the relationship between NTDs and human rights and describe human rights-based approaches to NTDs; and (2) examine how NTD advocacy, emphasizing the human rights consequences of NTDs, before human rights mechanisms and beyond, can support elimination efforts.

Human rights and NTDs

While the impact of NTDs on human rights may be interconnected with various rights (for example, the right to life with dignity, the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress, etc.), at its core, this relationship can best be understood through an examination of the rights to health and non-discrimination.

Right to health

The right to enjoy the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health (commonly referred to as the right to health) is enshrined in several international human rights treaties, as well as regional agreements and national constitutions and laws.[11] While there are several sources of this right, the main global treaties that enshrine this right are the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR),[12] the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women,[13] the International Convention on Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families,[14] the International Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination,[15] and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.[16]

In addition to these treaties, the meaning of the right to health has been furthered defined by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which monitors the implementation of state obligations under the ICESCR.[17] The committee outlines four important aspects of assessing the right to health: availability, accessibility (including non-discrimination and affordability), acceptability, and quality (also known as the AAAQ framework). It is important to note that the right to health does not guarantee the right to be healthy; instead, this right stands for an individual’s claim to the “enjoyment of a variety of goods, facilities, services and conditions necessary for its realization.”[18]

Identifying a relationship between NTDs and human rights does not automatically lead to action: given that states have different levels of resources, international law does not mandate the kind of health services to be provided, instead demanding their “progressive realization.”[19] However, states are recognized as having to fulfill certain minimum “core” obligations irrespective of resources, which includes ensuring access to health facilities and resources on a nondiscriminatory basis, especially for vulnerable and marginalized groups; the equitable distribution of all health facilities, goods, and services; and the adoption and implementation of a national public health strategy and plan of action, on the basis of epidemiological evidence, addressing the health concerns of the whole population. In addition, states should provide essential drugs, as defined by WHO.[20]

Non-discrimination

The right to equality and non-discrimination is essential to the international human rights framework generally and, as described above, to the fulfillment of the right to health.[21] The Human Rights Committee and the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights define discrimination as any distinction, exclusion, restriction, preference, or other differential treatment that is based on the prohibited grounds of discrimination and which has the intention or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment, or exercise of all fundamental rights and freedoms.[22] Prohibited grounds of discrimination include “race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.”[23] Non-discrimination and other rights of indigenous populations have also been specifically recognized both by the creation of specialist bodies on indigenous peoples in UN and regional human rights bodies, and through specific reference to indigenous peoples in human rights treaties, such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Relevant to NTDs, discrimination based on disability and health status are also generally prohibited.

The right to non-discrimination does not mean identical treatment for everyone in every situation. In some cases, differential treatment may not amount to discrimination if the criteria for different treatment are objective and reasonable and aim to advance progress toward a right or freedom.[24]

Human rights-based programming

Applying human rights principles to NTDs

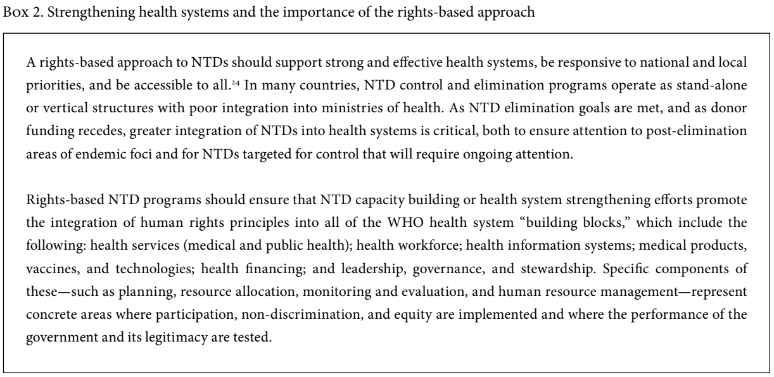

Public health programs based on human rights have been shown to improve service delivery and enhance equality, equity, inclusiveness, and accountability.[25] These programs, which traditionally include civil society engagement, high-level political leadership, and attention to equitable access to care, can also strengthen health systems and support successful NTD programs (see Box 2).[26]

WHO has described a rights-based approach to NTDs, emphasizing the human rights principles of participation, non-discrimination, and accountability.[28] Participation—and specifically the engagement of individuals and communities directly affected by NTDs— has been long recognized as critical to effective NTD programs.[29] Two examples, highlighted by Paul Hunt, the United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on the right to health from 2002 to 2008, include the engagement of patients’ associations for the control of leishmaniasis in Peru and community-directed treatment for onchocerciasis.[30] In the former case, individuals afflicted with leishmaniasis formed associations to advocate for and to promote and distribute treatment; these associations eventually evolved into a state-funded, regional control program. In the latter case, community-directed treatment for onchocerciasis supplanted more top-down approaches, empowering communities and providing greater flexibility for the distribution of preventive chemotherapy to interrupt onchocerciasis transmission. Community-chosen drug distributors in the program often subsequently became involved in other health activities, including immunization, water and sanitation-related activities, and development projects.

Similarly, a core component of the NTD response has been to increase transparency and accountability by mapping the distribution of disease, improving reporting of disease burden, and advocating for explicit objectives and goals to which governments can be held to account. A dramatic example is the change in the reported incidence of Guinea worm (dracunculiasis) before and after the initiation of eradication campaigns. For example, Nigeria and Ghana each officially reported about 3,000–5,000 cases of the disease to WHO annually in the 1980s. When the two countries conducted nationwide village-by-village searches for the disease in 1989, they enumerated over 650,000 and almost 180,000 cases, respectively. The surveillance effort also identified communities previously unknown to government officials.[31]

More rigorous measures of accountability—including formal assessments of whether governments, donors, and private actors are respecting, protecting, and fulfilling their obligations under human rights law—have been rare. Hunt addressed issues related to NTDs on country visits and in several reports to the Commission on Human Rights.[32] In his reports, he highlighted the obligations for governments, international organizations, and the private sector (including pharmaceutical companies) to prevent, control, and eliminate NTDs. He also noted the importance of community participation and was a strong advocate for addressing NTDs through a human rights framework.[33]

As global efforts to control or eliminate NTDs continue, three specific areas for rights-based approaches can be highlighted: inequity and populations at risk of being “left behind”; combatting stigma and discrimination and ensuring attention to mental health needs among people living with NTDs; and promoting patients’ rights and non-discrimination in health care settings.

Analyzing and addressing inequity

In 2017, WHO released a working paper entitled Towards Universal Coverage for Preventive Chemotherapy for NTDs: Guidance for Assessing “Who Is Being Left Behind and Why.”[34] The paper seeks to provide guidance to NTD program managers and partners on how to better monitor “differences in access to and impact of preventive chemotherapy” according to demographic and geographic characteristics that could reveal inequity, “identify barriers driving inequities and facilitators for coverage,” and “catalyze integration of a focus on ‘who is being left behind and why’ into on-going country level monitoring and evaluation of PC [preventive chemotherapy] to trigger remedial action as appropriate.”

In order to achieve more effective PC coverage, the working paper suggests that program managers and partners look at both quantitative and qualitative data, using the right to health’s AAAQ framework, to explore barriers and facilitating factors for effective PC coverage. Regarding availability, the paper explores various dimensions, including the availability of suitable drugs (for example, dosages and forms available for children), the availability of resources to allow medicines to reach all districts and communities (for example, transport for medicines), and resources to support community drug distributors in effectively reaching all communities (for example, transport for personnel). With regard to accessibility, it looks at geographic (for example, distances required to receive treatment), financial (for example, direct and indirect costs), and organizational and informational accessibility (for example, attention to opening times for treatment provision; information delivered in appropriate formats about the medicines). In terms of acceptability, the guidance looks at various dimensions, including the selection process for health service providers (for example, whether they come from inside or outside the communities), gender norms and relations, and the age-appropriateness of services. Finally, with regard to quality, it calls for program managers and partners to ensure that medicines are safe and of high quality.[35] The paper’s emphasis on the AAAQ framework as applied to PC coverage seeks to analyze the perceptions of different groups, communities, and health service providers and to address health inequity and gender inequality.

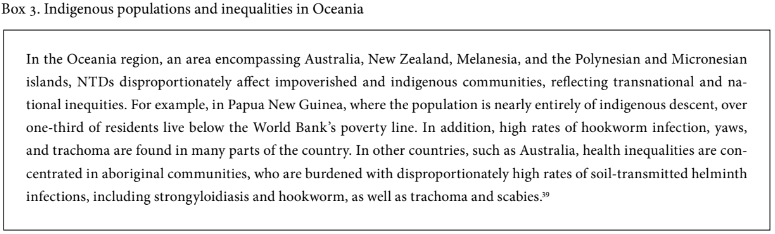

The need to address inequities has been highlighted in studies that have found differential rates of disease burden within NTD-endemic countries according to socioeconomic status, with the lowest socioeconomic groups disproportionately affected by NTDs.[36] For example, in Bihar, India, more than 80% of households in communities with high attack rates of visceral leishmaniasis belong to the two lowest quintiles (the poorest 40%) of the wealth distribution.[37] Indigenous communities and individuals in low socioeconomic groups unsurprisingly also face disproportionate burden of disease and often catastrophic consequence of NTD infection, including long-term indebtedness, even when diagnosis and medicines are provided free of charge (see Box 3).[38]

Global progress on NTDs also reflects inequities: A recent analysis by Wilma A. Stolk et al. estimated the change in NTD-related burden of disease using disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) between 1990 and 2010. In upper-income countries, DALYs attributed to NTDs decreased by 56%, compared to 16% in lower middle-income countries and 7% in low-income countries.[40] In addition, Cameron Seider et al. analyzed data from the 2013 demographic and health survey in Nigeria and found that access to child deworming increased linearly with level of maternal education (9.4% for children whose mothers had no formal education, compared to 42.5% for children whose mothers had more than secondary education) and wealth quintile (7.9% for the lowest wealth quintile, compared to 39.1% for the highest). It was also higher in urban (28.4%) than in rural (15.2%) areas.[41]

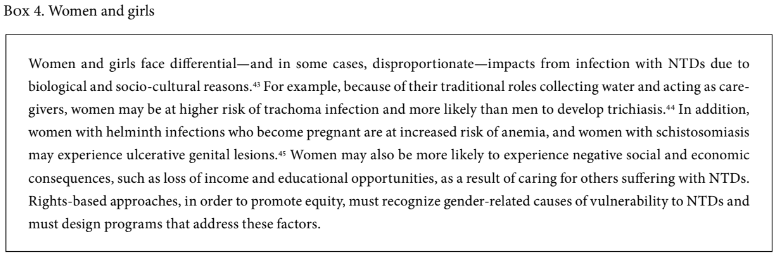

In addition to looking at socioeconomic and geographic disparities, greater attention should be paid to access to prevention and treatment for specific populations—including women (see Box 4), migrant or mobile populations, indigenous communities, and ethnic minorities. Each of these populations may be at increased risk of NTD infection or may be less able to access prevention and treatment. While the focus of NTD elimination programs is on achieving universal coverage, more effort is needed on understanding who is left out and why, as well as on increasing funding and support to communities struggling to reach elimination targets and on ensuring continued post-elimination interventions for individuals and communities, given that NTD goals for elimination as a public health problem explicitly allow for elimination to be certified despite low levels of disease transmission. The risk is that this will concentrate the remaining disease burden in the most vulnerable while simultaneously ending funding and outreach. Assuming that those not yet reached can be integrated into ongoing primary care efforts ignores the reason why they have not been reached to date.

Looking beyond mass drug administration to address stigma, social isolation, and mental health

Stigma and discrimination, exclusion from full participation in society, and an inability to access care or seek educational opportunities or employment can result in poor mental health, including depression and suicide. While access to general health care is often limited in communities with high rates of NTD burden, access to mental health care can be even less available.

Drawing on studies of the prevalence of depression among lymphatic filariasis patients in India, Togo, Haiti, and Sri Lanka (which ranged from 8% in Sri Lanka to 97% in India), a recent paper estimated that the global burden of mental illness associated with lymphatic filariasis was more than five million DALYs—nearly twice as high as the DALYs directly attributed to the disease itself.[45] A similar range of depression prevalence was found among individuals with leprosy (from 12.5% to 76%), and infection with cutaneous leishmaniasis has been found to be a significant predictor of poor mental health and higher rates of depression and anxiety.[46]

Interventions to address NTD-related stigma and social isolation are not new. Programs working with individuals with leprosy have long sought to reduce stigma by educating communities and alleviating irrational fears. A project funded by the UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases from 1998 to 2001 developed support groups in Haiti for individuals with lymphatic filariasis. These support groups integrated social support with treatment and financial assistance in order to help affected persons obtain appropriate footwear. An evaluation of the project found increased self-esteem, social relations, and quality of life among participants.[47]

Human rights-based approaches should recognize the comprehensive health and social needs of affected individuals and seek to expand both social support and access to effective treatment for mental health concerns.[48] The development of elimination criteria for lymphatic filariasis, developed by WHO, explicitly acknowledges the mental health burdens associated with the disease as part of the reason for the requirement for states to report on morbidity indicators in addition to evidence of the interruption of transmission.[49] Rights-based NTD programs should also recognize the potential need for mental health support for caregivers, who may suffer stigma from being associated with someone affected by NTDs or suffer other mental health concerns as a result of providing care to affected individuals.

Promote patients’ rights and non-discrimination in health care settings

Stigma and discrimination arise not only in community settings but also in health settings and among health care providers, which can result in the denial of care, poor-quality treatment, and abuse. Health care providers may be inadequately trained to care for certain NTDs or may feel overwhelmed by the care required. Alternatively, they may stigmatize or discriminate against individuals with NTDs because of perceptions of who is most at risk of disease or how it is acquired.

A qualitative study that looked at knowledge and health-seeking behaviors related to schistosomiasis in Kenya found that stigma and discrimination among health providers affected individuals’ willingness to seek care. The article quotes a female participant in a focus group discussion as saying, “The fear that maybe if they go to the hospital the doctor how will he see me or how will he take me. So because of stigma they may not go.”[50]

Another study, which examined knowledge of and attitudes toward podoconiosis among health professionals in public and private health institutions in Ethiopia, found that nearly all (98%) health professionals held at least one significant misconception about the cause of podoconiosis. Around half (54%) incorrectly considered podoconiosis to be an infectious disease and were afraid of acquiring podoconiosis while providing care. All care providers surveyed held one or more stigmatizing attitudes toward people with podoconiosis.[51]

Few quantitative studies have directly addressed the consequences of stigmatizing attitudes or discrimination in health settings for individuals with NTDs. However, studies on stigma and discrimination related to health-seeking behavior among people living with HIV found that people living with HIV who perceive high levels of HIV-related stigma are 2.4 times more likely to delay enrollment in care until they are very ill.[52] More research on attitudes toward NTDs among health care providers is needed, and where stigma and discrimination in health settings are identified as a barrier to care, interventions to educate health providers and empower individuals living with NTDs on their right to care are needed.

Human rights mechanisms and NTDs

In addition to implementing rights-based programs, addressing NTDs through human rights bodies provides a means to promote political will among, and accountability of, government leaders. Advocacy before specific human rights mechanisms may also lead to a greater global commitment to the NTD response while also ensuring that rights-based principles are strengthened.

UN human rights mechanisms

At the global level, the UN Human Rights Council is tasked with protecting, promoting, and strengthening human rights. It is an intergovernmental mechanism comprising 47 countries that are elected by the UN General Assembly.[53] As a subsidiary body of the General Assembly, the Human Rights Council has the ability to make recommendations directly to the General Assembly for further development and discussion.[54] It also has two human rights mechanisms linked to it: (1) the Special Procedures and (2) the Universal Periodic Review. The Special Procedures are independent experts with country or thematic mandates to report and advise on human rights. Hunt’s aforementioned work related to NTDs and human rights under the mandate of the Special Rapporteur on the right to health fall under this mechanism. The Universal Periodic Review is a state-driven process that reviews the human rights record of all UN member states.

To date, attention to NTDs within the Human Rights Council and its mechanisms has focused mainly on leprosy. In 2009, the Council held a consultation on the elimination of discrimination against persons affected by leprosy and their family members. As a result, the following year the General Assembly issued a resolution on this topic.[55] Since then, the Council has issued several resolutions and reports highlighting the problem of leprosy-related discrimination and ways to address it. In 2015, for example, the Council commissioned a study on the elimination of discrimination against persons affected by leprosy, which was presented to the Council in June 2017 and included a set of recommendations.[56] Also in June 2017, the Council established a mandate of the Special Procedures devoted to the elimination of discrimination against persons affected by leprosy and their family members.[57]

Another important human rights mechanism within the UN consists of treaty monitoring bodies, which are charged with monitoring and reviewing countries’ progress on their obligations under the core international human rights treaties. These bodies consist of independent experts who are elected for four-year terms. They issue general comments on treaty provisions, review states’ compliance with the treaties, hear individual complaints, and conduct country inquiries. When treaty bodies consider a state party’s compliance, they examine the state’s practices and issue concluding observations, which are recommendations on how the state can better fulfill its treaty obligations.[58]

These treaty bodies have issued many concluding observations on health-related rights. For example, the Human Rights Committee, which monitors states’ compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, has made several recommendations regarding access to sexual and reproductive health services, including safe abortion.[59] In addition, the Committee on the Rights of the Child has made health-related recommendations on child development, such as by highlighting the importance of ensuring access to health care for impoverished communities in Nepal and increasing access to clean water and sanitation services in Pakistan.[60] NTD advocacy could encourage these treaty bodies to raise awareness of and hold countries accountable to their commitments to the control and elimination of NTDs (see Box 5).

Courts

Courts, both regional and national, also provide an avenue for human rights and NTD accountability. Cases may be brought to court to seek redress for individual rights violations. They may also be brought to defend an issue of broad public interest (this is known as strategic litigation). In such cases, petitioners may challenge the validity of a law or the way that it is applied. The outcome of the case has a broad impact on society, beyond the lives of the litigants.[61] Courts can be transformative in supporting the realization of human rights, and specifically the right to health. Indeed, several courts have already issued groundbreaking precedents on health issues, such as reproductive rights and HIV.[62]

Nonetheless, few cases related to NTDs have been brought to the courts. In one case, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights found that Paraguay had violated an indigenous community’s rights to life and non-discrimination when it forced the community to live on uninhabitable land where community members were exposed to Chagas disease (among other hardships).[63] The court ordered the government of Paraguay to improve medical facilities; to implement water, sanitation, and hygiene programs (specifically parasitic disease control programs) in the community; and to report back on its efforts. It also directed the government to provide nearly US$1 million for a “community development fund” and for compensation for families of individuals who had died from the poor living conditions. In Argentina, the Supreme Court of Justice came to a similar conclusion—and issued protection orders—in a case in which the Human Rights Ombudsman alleged that the national and provincial governments had failed to ensure an indigenous community’s fundamental rights, including the rights to life and health.[64]

National human rights institutes

National human rights institutes (NHRIs) are another mechanism that can strengthen accountability related to NTD elimination. NHRIs are independent public agencies with a constitutional or legislative mandate to protect and promote human rights. They monitor and review a country’s human rights record and can make recommendations to governments, hear individual complaints, and provide public information on human rights.[65] NHRIs come in various forms: they can be commissions or ombudspersons, for instance, and they can have integrated mandates (for example, addressing human rights along with corruption and other matters).[66] Currently, there are 117 accredited NHRIs globally.[67] Several have already worked in some capacity on the right to health—for example, the Canadian Human Rights Commission has adopted a policy that explicitly states that the prohibition against disability-based discrimination includes discrimination based on HIV status.[68] Moreover, the National Human Rights Commission of India has issued recommendations on maternal anemia, HIV, and access to health care.[69]

Given that NHRIs can review a country’s general human rights record, they are well placed to monitor general health and NTD concerns, such as in the context of progress toward achievement of the SDGs, particularly concerning NTD elimination (goal 3), gender inequality (goal 5), and clean water and sanitation (goal 6).

Looking forward

A frequent concern about engaging in health and human rights advocacy is the opportunity cost and uncertainty about the potential impact from such efforts. Engaging human rights mechanisms is not always easy or timely, and the consequences of a UN treaty body resolution, an NHRI review, or even a court case may not always be clear. However, the benefits from increased engagement on NTDs within human rights mechanisms can be significant—and within the context of global NTD elimination efforts, the costs of advocacy are small.

The benefit of human rights advocacy on health issues can be clearly seen for other, previously neglected (and stigmatized) diseases, such as HIV, and increasingly for issues such as drug dependency and palliative care.[70] Similarly, human rights advocacy on NTDs can bring attention to the devastating effects of NTDs and the ongoing resource gap for disease prevention and treatment. Greater political commitment to NTDs, as well as more visibility in the general population, can result in prioritization in addressing NTDs at the national level and increased resource mobilization for the development of vaccines and treatments and for disease control programs. It will also encourage uptake of existing research, as well as more funding to build on the current evidence base. From a programmatic perspective, rights-based advocacy and engagement with human rights mechanisms could support more comprehensive structural responses that can lead to sustainable NTD control and elimination results. Increasing NTD-related work within human rights mechanisms can also address the social determinants of these diseases, contributing to a stronger overall system that benefits other issues, such as access to clean water and sanitation, extreme poverty, and inequality. Working with human rights mechanisms is thus a holistic way to address NTDs, calling for integration and accountability beyond mainstreaming NTD indicators.

Given the multisectoral nature of the goals and work under the SDGs, partnerships will be more important than ever. Innovative partnerships, such as Uniting to Combat NTDs, which has produced critical information on NTDs and NTD-related advocacy, will be essential for moving forward the response.[71] Establishing and strengthening links between NTD advocacy groups and social justice organizations can leverage and expand these partnerships. Increased linkages also promote cross-sector accountability within the partners, between sectors, and across human rights mechanisms.

Of course, human rights advocacy on NTDs is not a panacea. While recommendations from human rights mechanisms are useful, more work needs to be done to guarantee stronger follow-up and accountability by governments. It may also be worthwhile to consider linking the recommendations to indicators that countries already have to monitor, such as the SDG monitoring and evaluation framework.[72] This can be mutually beneficial to both the human rights system and the SDGs, as it addresses accountability issues at the country level.

Conclusion

Countries’ recognition of their obligation to fulfill the right to the highest attainable standard of health and to ensure that NTD programs incorporate human rights principles such as participation, non-discrimination, equity, and accountability may seem like a jargon-filled or complicated way of describing effective public health programs. However, public health interventions often privilege expediency over participation and equity and fail to guarantee non-discrimination. Accountability for government health systems, and for donor-funded efforts, is often lacking.

In the past 100 years, three out of every six disease eradication programs have failed. A common factor among those programs that failed was inadequate attention to social and political contexts.[73] Scaling up the linkages between NTDs and human rights, and securing greater investments in rights-based approaches within the NTDs response, can help ensure that local social and political actors support the global prioritization of NTD elimination and that NTD elimination programs are effective. A variety of institutions exist to advance human rights and can be used for NTD-related advocacy at the sub-national, national, and global levels. Increased engagement with human rights mechanisms can enhance accountability, promote non-discrimination, and support the participation of the most affected and marginalized in the development, implementation, and monitoring of NTD-related policies and programs. Such approaches are also consistent with and supportive of the cross-sectoral approach promoted by the SDGs.

Nina Sun, JD, is an independent consultant based in Geneva, Switzerland.

Joseph J. Amon, PhD, MSPH, is vice president for neglected tropical diseases at Helen Keller International in New York, USA.

Please address correspondence to Joseph Amon. Email: jamon@hki.org.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2018 Sun and Amon. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

[1]. World Health Organization, Working to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases: First WHO Report on Neglected Tropical Diseases (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010). Available at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44440/1/9789241564090_eng.pdf.

[2]. World Health Organization, Neglected tropical diseases. Available at http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/en.

[3]. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention., Neglected tropical diseases. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/ntd.

[4]. World Health Organization (2010, see note 1).

[5]. Ibid.

[6]. Ibid.

[7]. P. J. Hotez, A. Fenwick, L. Savioli, and D. H. Molyneux, “Rescuing the bottom billion through control of neglected tropical diseases,” Lancet 373/9674, pp. 1570–1575.

[8]. See Y. Stienstra, W. T. A. van der Graaf, K. Asamoa, and T. S. van der Werf, “Beliefs and attitudes towards Buruli ulcer in Ghana,” American. Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 67/2 (2002), pp. 207–213; A. Rinaldi, “Yaws: A second (and maybe last?) chance for eradication,” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2/8 (2002), p. e275; S. Wynd, W. D. Melrose, D. N. Durrheim, et al., “Understanding the community impact of lymphatic filariasis: A review of the sociocultural literature,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 85/6 (2007), pp. 421–500.

[9]. Human Rights Council, Progress report on the implementation of the principles and guidelines for the elimination of discrimination against persons affected by leprosy and their family members, UN Doc. A/HRC/AC/17/CRP.1 (2016).

[10]. World Health Organization, WHO Constitution (Geneva: World Health Organization, 1946).

[11]. For examples of regional agreements, see the European Social Charter, European Treaty Series No. 35 (1961); African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, OAU Doc. CAB/LEG/67/3/rev.5 (1981); Additional Protocol to American Convention on Human Rights in the Area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (Protocol of San Salvador) (1988); see also P. Hunt, R. J. Bueno de Mesquita, and L. Oldring, “Neglected diseases: A human rights analysis,” Special Topics in Social, Economic and Behavioural Research No. 6 (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007). For examples of states with constitutional protections for the right to health, see Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (1996), art 27; Constitution of the Republic of Uganda (1995), art 14; see also S. K. Perehudoff, Health, essential medicines, human rights and national constitutions (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008).

[12]. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI) (1966).

[13]. Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), G.A. Res. 34/180 (1979), art. 12.

[14]. International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, G.A. Res. 45/158 (1990).

[15]. International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD), G.A. Res. 2106A (XX) (1965).

[16]. Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), G.A. Res. 44/25 (1989).

[17]. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14: The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health (Article 12), UN Doc E/C.12/2000/4 (2000).

[18]. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and World Health Organization, Factsheet no. 31: The right to health. Available at http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/Factsheet31.pdf.

[19]. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see note 17).

[20]. Ibid.

[21]. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), G.A. Res. 2200Z (XXI) (1996), art. 26; ICESCR (see note 12), art. 2(2); CERD (see note 15), art. 1; CRC (see note 16), art. 2(1); CEDAW (see note 13), art. 1; Universal Declaration of Human Rights, G.A. Res. 217A (III) (1948), arts. 1, 2.

[22]. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 20: Non-discrimination in Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (Article 2, Paragraph 2 in ICESCR), UN Doc. E/C.12/GC/20 (2009), para. 7; Human Rights Committee, General Comment No. 18: Non-discrimination, UN Doc HRI/GEN/1/Rev.1 (1989).

[23]. ICCPR (see note 21), art. 26; ICESCR (see note 12), art. 2(2).

[24]. Human Rights Committee (see note 22), paras. 8, 13.

[25]. S. Gruskin, L. Ferguson, D. Tarantola, and R. Beaglehole, “Noncommunicable diseases and human rights: A promising synergy,” American Journal of Public Health 104/5 (2014), pp. 773–775.

[26]. F. Bustreo, P. Hunt, S. Gruskin, et al., Women’s and children’s health: Evidence of impact of human rights (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013).

[27]. P. Hunt, and G. Backman, “Health systems and the right to the highest attainable standard of health,” Health and Human Rights Journal 10/1 (2008), pp. 81–92.

[28]. World Health Organization, A human rights based approach to neglected tropical diseases (2010). Available at http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/Human_rights_approach_to_NTD_Eng.pdf.

[29]. World Health Organization, 15 years of the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control (APOC): 1995–2010 (2011). Available at http://www.who.int/apoc/magazine_final_du_01_juillet_2011.pdf.

[30]. Hunt et al. (see note 11).

[31]. D. Hopkins and E. Ruiz-Tiben, “Dracunculiasis (guinea worm disease): Case study of the effort to eradicate guinea worm,” in J. Selendy (ed), Water and sanitation-related diseases and the environment (Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), pp. 125–132.

[32]. See, for example, Paul Hunt, UN Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, Mission to the World Trade Organization, UN Doc. E/CN.4/2004/49/Add.1 (2004); UN Commission on Human Rights, The right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, UN Doc. E/CN.4/RES/2004/27 (2004).

[33]. Paul Hunt, UN Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, Mission to Uganda, UN Doc. E/CN.4/2006/48/Add.2 (2006); see also Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Uganda, Uganda and the United Nations human rights mechanisms. Available at http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/PublicationUgandaUNHRMechanisms.pdf.

[34]. World Health Organization, Towards universal coverage for preventive chemotherapy for NTDs: Guidance for assessing “who is being left behind and why” (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017).

[35]. Ibid., pp. 49–50.

[36]. See M. C. Kulik, T. A. Houweling, H. E. Karim-Kos, et al., “Socioeconomic inequalities in the burden of neglected tropical diseases,” abstract 67 of the 63rd annual meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (New Orleans, USA, November 2–6, 2014).

[37]. M. Boelaert, F. Meheus, A. Sanchez, et al., “The poorest of the poor: A poverty appraisal of households affected by visceral leishmaniasis in Bihar, India,” Tropical Medicine and International Health 14 (2009), pp. 639–644.

[38]. See, for example, S. Uranw, F. Meheus, R. Baltussen, et al., “The household costs of visceral leishmaniasis care in south-eastern Nepal,” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 7 (2013), p. e2062; D. Anoopa Sharma, C. Bern, R. Chowdhury, et al., “The economic impact of visceral leishmaniasis on households in Bangladesh,” Tropical Medicine and International Health 11 (2006), pp. 757–64; S. Sundar, R. Arora, S. Singh, et al., “Household cost-of-illness of visceral leishmaniasis in Bihar, India,” Tropical Medicine and International Health 15/Suppl 2 (2010), pp. 50–54; K. Grietens, A. Boock, H. Peeters, et al., “‘It is me who endures but my family that suffers’: Social isolation as a consequence of the household cost burden of Buruli ulcer free of charge hospital treatment,” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2 (2008), p. e321; R. Huy, O. Wichmann, M. Beatty, et al., “Cost of dengue and other febrile illnesses to households in rural Cambodia: A prospective community-based case-control study,” BMC Public Health 9 (2009), p. 155; P. T. Tam, N. T. Dat, X. C. P Thi, et al., “High household economic burden caused by hospitalization of patients with severe dengue fever cases in Can Tho province, Vietnam,” American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 87 (2012), pp. 554–558; P. Lutumba, E. Makieya, A. Shaw, et al., “Human African trypanosomiasis in a rural community, Democratic Republic of Congo,” Emerging Infectious Disease 13 (2007), pp. 248–254.

[39]. See K. Kline, J. S. McCarthy, M. Pearson, et al., “Neglected tropical diseases of Oceania: Review of their prevalence, distribution, and opportunities for control,” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 7/1 (2013), p. e1755; P. J. Hotez, “Aboriginal populations and their neglected tropical diseases,” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 8/1 (2014), p. e2286; C. Ko, D. Macleod, O. Pahau, et al., “Population-based trachoma mapping in six evaluation units of Papua New Guinea,” Ophthalmic Epidemiology 23/Supp 1 (2016), pp. 22–31.

[40]. W. Stolk, M. Kulik, E. le Rutte, et al., “Between-country inequalities in the neglected tropical disease burden in 1990 and 2010, with projections for 2020,” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 10/5 (2016), p. e0004560.

[41]. C. Seider, K. Gass, J. Snyder, et al., “To what extent is preventive chemotherapy for soil-transmitted helminthisasis ‘pro-poor’? Evidence from the 2013 demographic and health survey, Nigeria,” abstract 1134 of the 65th annual meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (Atlanta, USA, November 13–17, 2016).

[42]. P. Hoetez and M. Whitham. “Helminth infections: A new global women’s health agenda,” Obsterics and Gynecology 123/1 (2014), pp. 155–160; P. Hotez, “Empowering women and improving female reproductive health through control of neglected tropical diseases,” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 3/11 (2009), p. e559; H. Rilkoff, E. Tukahebwa, F. Fleming, and L. Cole, “Exploring gender dimensions of treatment programmes for neglected tropical diseases in Uganda,” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 7/7 (2013), p. e2312.

[43]. M. McDonald, “Neglected tropical and zoonotic diseases and their impact on women’s and children’s health,” in Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats, The causes and impacts of neglected tropical and zoonotic diseases: Opportunities for integrated intervention strategies (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011), p. A15; P. Courtright and S. West. “Contributions of sex-linked biology and gender roles to disparities with trachoma,” Emerging Infectious Disease 10/11 (2004), pp. 2012–2016.

[44]. A. K. Aderoba, O. I. Iribhogbe, B. N. Olagbuji, et al., “Prevalence of helminth infestation during pregnancy and its association with maternal anemia and low birth weight,” International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 129/3(2015), pp. 199–202; McDonald (see note 43).

[45]. T. Ton, C. Mackenzie, and D. Molyneux, “The burden of mental health in lymphatic filariasis,” Infectious Diseases of Poverty 4/1 (2015), p. 34.

[46]. E. Litt, M. Baker, and D. Molyneux. “Neglected tropical diseases and mental health: A perspective on comorbidity,” Trends in Parasitology 28/5 (2012), pp. 195–201.

[47]. J. Coreil, G. Mayard, and D. Addis, Support groups for women with lymphatic filariasis in Haiti (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003).

[48]. See J. Abdulmalik, E. Nwefoh, J. Obindo, et al., “Emotional consequences and experience of stigma among persons with lymphatic filariasis in Plateau State, Nigeria,” Health and Human Rights Journal (2018); A. Shahvisi, E. Meskele, and G. Davey, “A human right to shoes? Establishing rights and duties in the prevention and treatment of podoconiosis,” Health and Human Rights Journal (2018); H. Keys, M. Gonzales, M. B. De Rochars, et al., “Social exclusion and the right to health in the Dominican Republic: Implications for lymphatic filariasis elimination,” Health and Human Rights Journal (2018).

[49]. World Health Organization, Validation of elimination of lymphatic filariasis as a public health problem (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007).

[50]. G. Odhiambo, R. Musuva, V. Atuncha, et al., “Low levels of awareness despite high prevalence of schistosomiasis among communities in Nyalenda informal settlement, Kisumu City, Western Kenya,” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 8/4 (2014), p. e2784.

[51]. B. Yakob, K. Deribe, and G. Davey, “Health professionals’ attitudes and misconceptions regarding podoconiosis: Potential impact on integration of care in southern Ethiopia,” Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 104/1(2010), pp. 42–47.

[52]. H. Gesesew, A. Tesfay Gebremedhin, T. Demissie, et al., “Significant association between perceived HIV related stigma and late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” PLoS One 12/3 (2017), p. e0173928.

[53]. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, United Nations Human Rights Council: About the HRC. Available at http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/Pages/AboutCouncil.aspx.

[54]. UN News Centre, FAQs on the Human Rights Council. Available at http://www.un.org/News/dh/infocus/hr_council/hr_q_and_a.htm.

[55]. United Nations General Assembly, Res. 65/215, UN Doc. A/RES/65/215 (2011).

[56]. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Study on the implementation of the principles and guidelines for the elimination of discrimination against persons affected by leprosy and their family members: Report of the Human Rights Council Advisory Committee, UN Doc. A/HRC/35/38 (2017); Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Human Rights Council Advisory Committee: Leprosy. Available at http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/AdvisoryCommittee/Pages/Leprosy.aspx.

[57]. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Elimination of discrimination against persons affected by leprosy and their family members, UN Doc. A/HRC/RES/35/9 (2017).

[58]. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Monitoring the core international human rights treaties. Available at http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/Pages/WhatTBDo.aspx.

[59]. Human Rights Committee, Concluding Observations to the Philippines, UN Doc. CCPR/C/PHL/CO/4 (2012), para. 13. See also para. 14.

[60]. Committee on the Rights of the Child, Concluding Observations to Nepal, UN Doc. CRC/C/NPL/CO/3-5 (2016), paras. 47–49.

[61]. E. Rekosh, K. Buchko, and V. Terzieva, Pursuing the public interest: A handbook for legal professionals and activists (New York: Columbia University School of Law, 2001), pp. 81–82.

[62]. For example, see Whole Women’s Health et al. v. Hellerstedt, Comissioner, Texas Department of State Health Services, et al. (2016), Case No. 15-274 (Supreme Court of the United States); Minister of Health v. Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) and Others (2002), 5 South African Law Report 721 (Constitutional Court of South Africa).

[63]. Xákmok Kásek Indigenous Community v. Paraguay (2010), (ser. C) No. 214 (Inter-American Court of Human Rights).

[64]. Defensor del Pueblo de la Nación c/ Estado Nacional y otra (Provincia del Chaco) s/proceso de conocimiento (2007), D. 587. XLIII (Supreme Court of Argentina).

[65]. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, National human rights institutions: History, principles, roles and responsibilities, Professional Training Series No. 4 Rev. 1 (2010). Available at http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/PTS-4Rev1-NHRI_en.pdf.

[66]. Ibid.

[67]. For NHRI accreditation, see Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions, GANHRI sub-committee on accreditation (SCA). Available at https://nhri.ohchr.org/EN/AboutUs/GANHRIAccreditation/Pages/default.aspx.

[68]. Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, “Protection against discrimination based on HIV/AIDS status in Canada: The legal framework,” HIV/AIDS Law and Policy Review 10/1 (2005), p. 25.

[69]. National Human Rights Commission of India, Human rights issues. Available at http://nhrc.nic.in/hrissues.htm#no20.

[70]. Open Society Foundations, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, United Nations Development Program, and Joint United Nations on HIV/AIDS, Human rights and HIV/AIDS: Now more than ever; 10 reasons why human rights should occupy the center of the global AIDS struggle (2009). Available at https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/nmte_20090923_0.pdf; J. J. Amon, R. Pearshouse, J. E. Cohen, and R. Schleifer, “Compulsory drug detention centers in China, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos: Health and human rights abuses,” Health and Human Rights Journal 15/2 (2013); J. J. Amon, R. Pearshouse, J. E. Cohen, and R. Schleifer, “Compulsory drug detention in East and Southeast Asia: evolving government, UN and donor responses,” International Journal of Drug Policy 25/1 (2014), pp. 13–20; D. Lohman and J. Amon, “Evaluating a human rights-based advocacy approach to expanding access to pain medicines and palliative care: Global advocacy and case studies from India, Kenya, and Ukraine,” Health and Human Rights Journal 17/2 (2015).

[71]. Uniting to Combat Neglected Tropical Diseases, Progress and scorecards. Available at http://unitingtocombatntds.org/impact.

[72]. United Nations, SDG indicators: Official list of SDG indicators. Available at http://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/indicators-list.

[73]. S. Taylor, “Political epidemiology: Strengthening socio-political analysis for mass immunization; Lessons from the smallpox and polio programmes,” Global Public Health 4/6 (2009), pp. 546–560.