Nada Amroussia, Isabel Goicolea, and Alison Hernandez

Abstract

Although Tunisia is regarded as a pioneer in the Middle East and North Africa in terms of women’s status and rights, including sexual and reproductive health and rights, evidence points to a number of persisting challenges. This article uses the Health Rights of Women Assessment Instrument (HeRWAI) to analyze Tunisia’s reproductive health policy between 1994 and 2014. It explores the extent to which reproductive rights have been incorporated into the country’s reproductive health policy, the gaps in the implementation of this policy, and the influence of this policy on gender empowerment. Our results reveal that progress has been slow in terms of incorporating reproductive rights into the national reproductive health policy. Furthermore, the implementation of this policy has fallen short, as demonstrated by regional inequities in the accessibility and availability of reproductive health services, the low quality of maternal health care services, and discriminatory practices. Finally, the government’s lack of meaningful engagement in advancing gender empowerment stands in the way as the main challenge to gender equality in Tunisia.

Introduction

Tunisia is regarded as a pioneer in the Middle East and North Africa in terms of women’s status and rights.1 In 1956, it was the first country in the region to abolish polygamy and, in 1973, was the first to legalize abortion. Moreover, it is the only country in the region that has withdrawn all its reservations to the Convention of Elimination of All Forms of Discriminations against Women (CEDAW). Since 1966, Tunisia has also run a successful family planning program. As part of this program, the National Board for Family and Population was created in 1973. In 1994, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) designated Tunisia as a Centre for Excellence in terms of its population activities.2

The 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) marked an important transition in Tunisia’s population policy, as it led the country to abandon its focus on purely demographic concerns and instead embrace reproductive health as a priority per se in national health programs.4 In fact, despite the importance of the Millennium Development Goals and the Sustainable Development Goals in putting issues such as maternal health, gender equality, and women’s empowerment on the international agenda, the ICPD Programme of Action is still regarded as the most comprehensive international document on sexual and reproductive rights.4

Since 1994, women’s reproductive health indicators in Tunisia have shown improvements. By 2012, the unmet need for contraception just 7%.5 Skilled delivery attendance increased from 76.3% in 1990 to 97.6% in 2013, and the maternal mortality ratio declined from 91 per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 46 per 100,000 in 2013.6 However, it has not all been progress. According to a 2010 shadow report submitted to the CEDAW Committee by Tunisia’s Democratic Women’s Association, women in Tunisia are subjected to numerous violations of their sexual and reproductive rights, including discrimination against unmarried women, virginity testing, and the criminalization of homosexuality.7

Over the last five years, Tunisia has undergone a political transition characterized by new aspirations for democracy and respect for human rights. Throughout this period, women’s rights, including their sexual and reproductive rights, have been one of the most debated topics in the new republic. As a contribution to the post-democratic transition debates concerning women’s rights, this article presents a gender-sensitive human rights-based analysis of Tunisia’s reproductive health policy between 1994 and 2014.

Theoretical framework

After a long history of marginalization, reproductive rights were globally recognized in the ICPD. Although these rights are still controversial and contested in many settings, they do not represent a new set of rights. Indeed, they reflect the very rights that have been long established in human rights treaties—for example, the right to life, the right to physical integrity and the right to health. As fundamental human rights, reproductive rights are universal, inalienable, indivisible, and interrelated; they apply to all human beings equally without discrimination, and they require the application of the principles of participation, inclusion, accountability, and the rule of law. Hence, states are obligated to respect, protect, and fulfill these rights, and citizens can hold the state accountable for this obligation.8 This constitutes the basis for a human rights-based approach.

Women’s right to reproductive health entails the government’s responsibility in providing available, accessible, acceptable, and high-quality reproductive health care services, as well as ensuring that women can make free decisions regarding their sexuality and reproduction.9 According to General Comment No. 12 of the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, availability refers to the adequate supply of reproductive health facilities, goods, and services. Accessibility requires that these services be non-discriminatory, physically accessible, affordable, and accessible in terms of their information. Acceptability means that these services and goods must be culturally and ethically acceptable, while quality means that they must be medically and scientifically appropriate.10

Women’s reproductive health and rights are affected by the social organization of gender relations. Gender inequality is responsible for women’s vulnerable status and limits their abilities to make free decisions about their bodies and their lives.11 It also leads to harmful practices, such as gender-based violence, which can affect women’s health.

Gender empowerment and women’s rights, including reproductive rights, are inextricably linked.12 For example, the right to have control over and to make free decisions about reproduction and reproductive health requires empowerment; women cannot enjoy this right if they are economically dependent or politically excluded.13 Education is also crucial to improve women’s knowledge about the availability of reproductive health services and to ensure their access to these services.14 Moreover, gender empowerment improves women’s economic and social status, thus creating a positive environment in which they can claim their rights.15 Examining the state of gender equality is therefore critical to understanding the environment that shapes women’s capacity to exercise their rights.

In this light, we used the Health Rights of Women Assessment Instrument (HeRWAI) to analyze Tunisia’s reproductive health policy. Our aim was threefold: (1) to explore the extent to which reproductive rights have been incorporated into the country’s reproductive health policy; (2) to determine gaps in the implementation of this policy; and (3) to examine how the gender empowerment process has been influenced by this policy.

Methodology

Study setting

Located in North Africa, Tunisia is a middle-income country with a population of 11 million.16 According to the 2014 Constitution, Tunisia has been a republic since 1956. However, it was not until 2011 that the country held its first democratic elections. Regional inequities are considered the main barrier to socioeconomic development. Poverty and unemployment are concentrated in the predominately rural Central West and North West regions, where 26%–32% of the population lives in poverty and 20%–22% are unemployed.17 Furthermore, Tunisia’s cultural context is highly influenced by religion. Under article 1 of the Constitution, Islam is considered the official religion of the country, and the majority of Tunisians are Muslims. Nevertheless, since gaining independence, Tunisia has tried to adopt “secular policies” aimed at the country’s modernization.18

Methods

HeRWAI tool

We applied HeRWAI, an analytical tool developed by Aim for Human Rights, to perform an analysis of Tunisia’s reproductive health policy. Built on the human rights framework, this tool assesses the impact of policies on women’s health and rights by comparing what is actually happening to what should happen according to the government’s human rights commitments.19

The HeRWAI analysis is performed in six steps:

- Identify the policy that affects women’s health and rights.

- Explore the government’s human rights commitments.

- Explore the government’s capacity to implement the selected policy.

- Assess the impact of the policy on women’s health rights.

- Hold the government accountable for its obligations to respect, protect, and fulfill human rights.

- Formulate recommendations and an action plan based on the findings of the analysis in order to enforce the realization of women’s rights.20

HeRWAI is one of the most frequently used impact assessments tools for health and human rights. Focusing on women’s right to health, it is designed primarily to generate evidence for use in advocacy and lobbying. The tool’s flexibility facilitates its adaptation to different types of studies.

Adaptation of HeRWAI in this study

We adapted HeRWAI to a three-stage process based on our three research aims:

- Stage 1: Incorporation of reproductive rights into national policy

First, we collected official data related to reproductive health policy in Tunisia (laws, national programs, and strategies) through an online review of government websites. Included in this data were collaborative strategies between Tunisia and the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNFPA. We considered three international human rights commitments for our analysis: the ICPD Programme of Action, the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, and CEDAW. Our assessment of the incorporation of reproductive rights was guided by four indicators proposed by Guang-zhen Wang and Vijayan Pillai: the right to legal abortion; the right to use contraceptive methods; the right to interracial, interreligious, and civil marriage; and the equality of men and women during marriage and divorce proceedings.23 Additionally, based on the definition of reproductive rights adopted in the ICPD Programme of Action, we added a fifth indicator: the right to reproductive health.24

- Stage 2: Gaps in the implementation of the reproductive health policy

To assess the impact of the reproductive health policy on women’s right to reproductive health, we conducted a literature review using the search terms “reproductive health,” “reproductive rights,” “maternal health,” and “sexual rights,” with the setting “Tunisia.” The literature review included quantitative and qualitative studies, as well as reports published by international organizations. Due to the limited availability of data, we included all identified sources that focused on reproductive health in Tunisia and were published between 1994 and 2014. Data related to the government’s implementation capacity was collected through an online review of government websites.

To determine the gaps in implementation regarding women’s right to reproductive health, we used the four criteria outlined in General Comment No. 14: availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality of reproductive health services.25

- Stage 3: Status of gender equality and the realization of women’s rights

This stage addressed the influence of the reproductive health policy on gender empowerment in Tunisia. Our analysis was based on a literature review covering the period 1994–2014. We used the search terms “gender empowerment,” “gender equality,” “women’s rights,” and “gender equity,” along with the setting “Tunisia.”

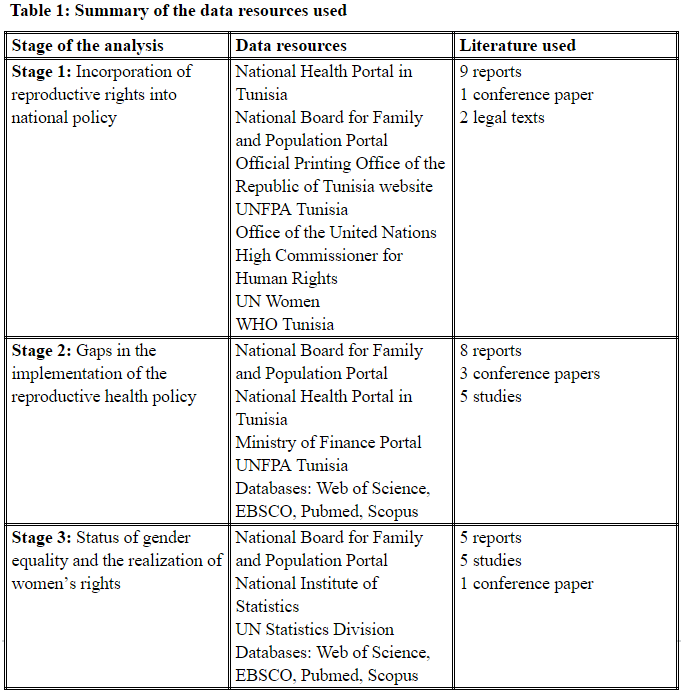

During the three stages of analysis, we considered data available in English, French, and Arabic. The table below summarizes the main data resources used.

Findings and discussion

Incorporation of reproductive rights into national policy

Promulgating laws that protect reproductive rights constitutes the first step toward the integration of these rights into reproductive health policies, as these laws represent the legal framework for the formulation of strategies and programs related to reproductive health. In Tunisia, the right to use contraceptives and the right to abortion have been protected under law since 1961 and 1973, respectively.26 The right to reproductive health has been incorporated through the guarantee of service provision in various national health programs. Free access to contraception, abortion, and counseling for all women is ensured through the country’s family planning program.27 Moreover, as part of Tunisia’s antenatal program, initiated in 1990, and its National Strategy to Reduce Maternal and Neonatal Mortality, initiated in 1998, pregnant women are ensured the right to five prenatal consultations and two postnatal consultations free of charge.28 Breast cancer screening and cervical cancer screening have also been introduced into basic health care services as part of the country’s National Cancer Control Plans.29

Since 2001, as part of the National Program to Combat Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs) and HIV/AIDS, free access to antiretroviral drugs has been guaranteed, along with free, voluntary, and confidential HIV tests. The prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections has also been included in primary health care services.30 However, access to HIV treatment for vulnerable populations (intravenous drug users, homosexuals, and sex workers who are not authorized by the Ministry of Internal Affairs) is hindered by Law 92-52, which severely penalizes drug use, and by articles 230–231 of the Penal Code, which impose jail sentences in cases of sodomy and illegal prostitution.31

Despite this increased availability of health services, however, the attainment of reproductive health is limited by laws that perpetuate gender inequality. Women’s right to civil marriage is violated by an administrative regulation that prohibits Tunisian women from marrying non-Muslim men.32 Moreover, gender inequality during marriage is maintained by article 23 of the country’s Personal Status Code, which names the husband as the head of the family. Finally, inequality in legal rights can be observed in the case of divorce, where woman are at risk of losing their right to custody of their children if they remarry, while men are not.33

Our analysis of national legislation and health strategies demonstrates that although Tunisia started adopting laws promoting reproductive rights (mainly the right to contraception and the right to abortion) in the 1960s, its progress since ICPD has been slow. This calls into question the government’s commitment to place reproductive rights at the core of its reproductive health policy, as it agreed to do when it signed the ICPD Programme of Action and the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action.34 As Adrienne Germain et al. have asserted, advancing reproductive rights requires that the government implement accountability mechanisms to monitor progress and redress shortcomings. While Tunisia submits periodic reports to United Nations treaty bodies, it has not developed national accountability mechanisms to monitor the realization of reproductive rights.35 Developing standards and benchmarks to guide such monitoring is critical for allowing a more comprehensive assessment of the realization of reproductive rights in Tunisia.36

Gaps in the implementation of the reproductive health policy

In Tunisia, women’s right to reproductive health has been incorporated into various plans and programs. Nevertheless, there is no comprehensive strategy to include the package of essential reproductive services within the country’s primary health care system, as recommended in the ICPD Programme of Action. UNFPA has stated that the absence of consensus on an affordable basic primary health care package in Tunisia represents a barrier to universal access to reproductive health care.37 Moreover, despite the private sector’s growing role in the provision of reproductive health services, there are no coordination plans with the government to ensure the affordability of essential reproductive health care services.

In 2012, the total government expenditure in health was estimated to be 7% of the national budget.38 In the last two years, 15% of the Ministry of Health’s budget was allocated to the implementation of basic health care programs, including reproductive health programs, yet only 13.8% of this portion was allocated to the National Board for Family and Population. Additionally, our exploration of the these budgets revealed that, in 2014, only 10% of all human resources were allocated to the implementation of basic health programs.

Regional inequities in the accessibility and availability of reproductive health services

Reproductive health services are provided mainly by a network of 2,091 primary health care centers, 36 reproductive health centers, and 20 youth centers.39 According to WHO, 95% of Tunisia’s primary health care centers are geographically accessible to the population.40 However, as noted by UNFPA, only 10% of the primary health care centers situated in the North West, Central West, and South East provide a basic package of reproductive health services, compared to the good availability of these services in the North and Central East regions.41 In addition, in rural areas, family planning services are provided via mobile clinics.42 Despite the efficiency of mobile units in overcoming the poor health care infrastructure in many areas, the number and coverage of these units have decreased significantly in recent years; indeed, in 2013, only one mobile clinic was available.43

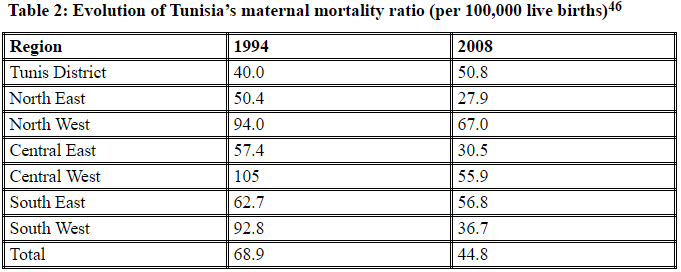

Regional inequities in women’s access to reproductive health care are further reflected in women’s reproductive health indicators, such as maternal mortality ratios (see Table 2). In 1994 and 2008, the maternal mortality ratios in the North West, Central West, and South East were remarkably higher than the nationwide ratios.44 Tunisia’s national committee on maternal mortality found that the high ratios in the North West and Central West were due to a lack of blood supply, equipment, and medicines, as well as insufficient human resources.45

Low quality of maternal health

As the table above shows, maternal mortality ratios between 1994 and 2008 also increased in urban Tunis, which reflects the low quality of the city’s maternal health services. In fact, a study conducted in 2010 demonstrated that the low quality of maternal care services, including delays in diagnoses and inadequate treatment, explained the capital’s increased maternal mortality during this period.47 Moreover, another study estimated that 75.3% of maternal deaths in public hospitals between 1999 and 2004 were avoidable. These deaths were due mainly to underestimation of the woman’s risk, inadequate follow-up during the postpartum phase, and delays in care.48

The persistence of regional inequities in women’s access to reproductive health care and the low quality of maternal care point to the government’s failure to mobilize sufficient human and financial resources to implement national reproductive health programs. One of the main barriers to improved health service delivery in Tunisia is the excessive centralization of decision making.49 As explained by Tim Ensor and Jeptepkeny Ronoh, the government must decentralize this process if it hopes to implement reproductive health policies tailored to local populations’ needs and to improve the efficiency of health system delivery. Health system decentralization can also empower local communities when it involves participatory approaches in program planning and implementation.50

The capacity to implement reproductive health programs also depends on the macroeconomic context. Sumati Neir, Sarah Sexton, and Preeti Kirbat have pointed out that structural adjustment programs and the lack of international funding for reproductive health programs have contributed significantly to many countries’ failure to implement the ICPD Programme of Action.51 According to the authors, structural adjustment programs have led to a decline in public health expenditures in low- and middle-income countries, thus reducing their capacity to provide adequate reproductive health services.52 Tunisia’s structural adjustment program, which has been in place since 1986, has led public spending on health to decline from 10% during the 1970s and 1980s to 5.7% in 2008.53 However, there are no published studies that explore the impact of this program on the country’s public health system.

A study conducted in 2004 to assess the realization of economic, social, and cultural rights in Tunisia found that regional inequities negatively affected not only the right to health but also the rights to education, to work, to housing and access to drinkable water, and to a decent standard of living.54 The North West and Central West were considered the most deprived regions. The findings of these two studies confirm the interdependency among fundamental human rights, demonstrating that women’s reproductive rights cannot be fully realized without addressing the underlying determinants of health.

Discriminatory practices

Discriminatory practices represent one of the main barriers to women’s access to adequate reproductive health services. In Tunisia, such practices affect primarily unmarried women and people living with HIV. According to the family health survey conducted by the National Board for Family and Population in 2002, health workers considered spousal consent a normal precondition for providing contraceptives to women, despite the fact that no official instructions justifying this practice exist.55 This precondition not only excludes single women from accessing contraceptives but also interferes with women’s right to make free choices about contraception. Another study, conducted in 2012 in four countries where abortion is legal, found that 26% of Tunisian women in the study had been denied abortion: 7% because of the gestational period and 15% because of nonmedical reasons, including being single, the absence of spousal consent, and non-indicated medical tests.56

Furthermore, according to WHO, single women are excluded from the primary health care system’s treatment and care for sexually transmitted infections, as these services are geared mainly toward married women.57 Discriminatory attitudes against single women have also been found in the private health sector. A study conducted in 2011 to assess the availability and accessibility of emergency contraception in Tunisia revealed that some pharmacies had adopted a policy of not providing contraceptives to single women.58

Discrimination against single women seeking contraception and abortion is due largely to societal taboos around extramarital and premarital sexual relations.59 Indeed, the only culturally accepted “framework” for sexual relations in Tunisia is marriage.60

Status of gender equality and the realization of women’s rights

Reproductive health policy has played an important role in women’s empowerment in Tunisia. The promulgation of the Personal Status Code in 1956 marked a shift in women’s emancipation, as it improved their legal and social status in the family by abolishing polygamy and unilateral repudiation and by setting the legal age of marriage for women at seventeen.61 More recent changes in the code have further supported gender equality within marriage through the abolition of the wife’s duty to obey to her husband (1993) and the establishment of the system of conjugal partnership of gains (1998).62 These achievements have been strengthened by the guarantee of free access to education, which has been in place since 1958, and mandatory access to education, which has been in effect since 1991.63 As a result, Tunisia has increased gender parity in secondary and tertiary education since 2000.64 Recently, between 2006 and 2013, the number of female students graduating from college was almost twice that of male students.65

Despite these signs of progress, however, Tunisia is far from achieving gender equality. Women’s unequal status in marital relationships continues to operate through non-egalitarian legislation and deeply embedded patriarchal attitudes and social norms. Legislation that upholds dowry payments, inequality in inheritance, and men’s leadership in households represents barriers to women’s equality. Furthermore, there is a decoupling between the legal rights of women in Tunisia and their “real” status in society and the family. Patriarchal stereotypes propagate women’s subordination and deprive them from enjoying the rights enshrined in the Personal Status Code.66 Gender inequality in its most severe form is reflected by the findings of the 2010 National Survey on Violence against Women, which revealed that 47.6% of women between the ages of 18 and 64 have experienced at least one form of gender-based violence during their lives. The survey also revealed that the violence occurs first in the intimate sphere (e.g., at the hands of a husband or partner) and then in the family sphere (e.g., by a father or brother).67

Moreover, despite achievements in education, women have higher rates of illiteracy and lower rates of employment than men. Tunisia’s last census, conducted in 2014, revealed a 25% illiteracy rate among women, compared to a rate of 12.5% among men.68 In the North West and Central West, the illiteracy rate among women reached 40%. Furthermore, women’s workforce participation rate remained unchanged—at 26%—between 2006 and 2014. Finally, in 2014, the unemployment rate among college-educated women was 40.8%, compared to just 20.2% among their male counterparts.69

Despite the adoption of laws that ensure gender equality in employment, many factors contribute to women’s low economic participation in Tunisia. Discriminatory practices in the private sector lead to unequal opportunities for women when they enter the labor market, restricting their chances of being hired, earning an equal wage, and accessing leadership positions.70 Moreover, conservative traditions dictating that women’s main role be that of mother or wife challenge their efforts to achieve economic autonomy.71

Another aspect of gender inequality can be seen in women’s participation in decision making and political life. In 2009, women accounted for 26.17% of all parliamentarians, with this number rising to 29% in 2011 and 33.18% in 2014.72 Nonetheless, a study examining their role in Parliament suggested that their participation in decision making was limited.73 In 2011, the government adopted a gender parity law requiring the alternation of male and female candidates in each electoral list; however, women represented only 7% of the heads of these lists in the 2011 legislative election, reflecting their restricted role.74 Additionally, women occupied only 7.3% of decision-making posts within national-level public agencies.75

Barriers to the realization of gender equality and reproductive rights

The liberalization of abortion, greater rights to contraception, and the promotion of women’s status within the family represent important steps in women’s empowerment. However, stagnation in the advancement of reproductive rights in the last 20 years has constrained progress toward real gender equality.

This slow progress can be attributed in part to women’s limited participation in economic and political life, which has restricted their ability to advocate for their rights, as well as their opportunities to effect change in national laws and policies. Women’s limited participation in political decision-making was exacerbated by the country’s general climate of repression prior to 2011, in which human rights, including women’s rights, were systematically violated.76 As argued by Vijayan K. Pillai and Rashmi Gupta, democracy is a prerequisite to true gender equality, for women’s empowerment starts with a recognition of their rights as citizens.77 Democratic transitions in Latin America and Africa indicate that women’s equality is strengthened as democracy enables them to claim their rights, including their reproductive rights.

Social development is also important for promoting gender equality and reproductive rights, as policies targeting social inequalities increase women’s access to education, jobs, and better health.78 The high rates of illiteracy among women in the North West and Central West demonstrate that women’s empowerment in Tunisia is greatly affected by regional socioeconomic inequities. Rural women have not benefitted as much from the social and legal progress made in women’s status at the national level, as the marginalization of rural areas excludes them from participating in political and socioeconomic life.79

Moreover, gender empowerment is a complex process affected not only by the socioeconomic and political context but also by cultural norms and religion. In recent years, women’s empowerment in Tunisia has faced a backlash from a conservative wave of Islam that interprets the religion as confining women to a subordinate role in society.80 In fact, the emergence of conservative Islamic ideology in Tunisia has been accompanied by a resurgence of traditional patriarchal norms in society that threaten women’s rights. Since patriarchal norms in Tunisia usually use religion as a moral justification, real gender equality cannot be achieved without a separation between religion and politics.81

Finally, gender empowerment requires that the government adopt effective interventions around gender equality. Tunisia’s commitment to the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action means that it must mainstream gender in all policies and programs as part of a strategic approach to achieve gender equality. Although Tunisia has begun to do this in recent years through the creation of gender focal points in ministries, the missions of these focal points have yet to be defined.82

Methodological considerations

This study applied a human rights assessment tool to systematically examine the reproductive health policy of a country considered to be a pioneer in the region. Our findings reveal critical limitations in the incorporation of reproductive rights and in the implementation of Tunisia’s reproductive health policy. Nevertheless, our study drew from secondary data only, and the data available was limited. Further research is needed to explore women’s access to reproductive health services, particularly in underprivileged areas; the acceptability and quality of these services; and health providers’ interpretation of reproductive rights. This will enable a fuller assessment of the implementation of Tunisia’s reproductive health policy. Further research is also needed to explain the gaps in the policy’s implementation and to indicate pathways for enhancing the realization of reproductive rights in Tunisia.

Since 2011, Tunisia has undergone an important political transition, which may be having an impact on the reproductive health policy. However, due to a lack of data, our analysis did not explore the impact of this transition on the formulation and implementation of the country’s reproductive health policy. A recent article by Pinar Ilkkaracan looks at this transition’s impact on reproductive rights, indicating that women’s access to safe abortion has been further restricted in the wake of Islamists’ political ascendance in 2011.83 Nonetheless, further research is needed to capture the impact of this political transition on the interpretation and implementation of reproductive rights.

Conclusion

Although Tunisia has made important steps toward incorporating reproductive rights into its reproductive health policy, there are significant shortcomings in the implementation of this policy, in addition to a lack of meaningful adoption of actions to achieve gender equality.

Analyzing policy through a human rights lens is crucial to improving women’s access to reproductive health care. Issues such as the denial of legal abortion and discriminatory attitudes can be considered human rights abuses, which the government has the responsibility to prevent. In this sense, it is necessary to reform health professionals’ training to improve their capacity to deliver reproductive health services that meet human rights standards. As our study reveals, one of the main gaps in the implementation of Tunisia’s reproductive health policy is the imbalance across regions in terms of the accessibility and availability of reproductive health services. Reducing regional inequities in women’s access to reproductive health care requires tackling their root causes: poor infrastructure, poverty, and political marginalization.

Advancing reproductive rights and achieving gender equality are primarily the government’s responsibility; however, these aims also depend on the advocacy efforts of women, youth, and civil society. The process of advancing reproductive rights should be conceptualized within a broader framework that links human rights to social justice. This is particularly relevant in Tunisia’s current political context, as the new Constitution explicitly protects the right to health and outlines the state’s obligation to enforce women’s rights and to protect women from violence. New, constitutional spaces for holding the state accountable to its commitments have thus been opened. Our study provides evidence that regional inequities in women’s access to reproductive health services, the low quality of maternal health services, and discriminatory practices affecting single women are critical points for demanding accountability.

Nada Amroussia, MSc, is a master’s student at the Department of Epidemiology and Public Health Sciences, Umea University, Sweden.

Alison Hernandez, MPH, PhD, is a researcher at the Department of Epidemiology and Public Health Sciences, Umea University Sweden.

Isabel Goicolea, MD, PhD, is Associate Professor at the Department of Epidemiology and Public Health Sciences, Umea University, Sweden.

Please address correspondence to the authors c/o Nada Amroussia, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Umea University S- 901, 85 Umea, Sweden, Email:amroussia.nada@hotmail.com.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2016 Amroussia, Hernandez, and Goicolea. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, ConcludingObservations on Tunisia, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/TUN/CO/6 (2010).

- UNFPA, Population Reference Bureau, Country profiles for population and reproductive health: Policy development and indicators (New York: UNFPA, 2003), p. 216.

- Office National de la Famille et de la Population, Rapport d’activité 2009 (Tunis: Office National de la Famille et de la Population, 2010).

- S. Sippel, “ICPD beyond 2014: Moving beyond missed opportunities and compromises in the fulfilment of sexual and reproductive health and rights,” Global Public Health 9 (2014), pp. 620–630.

- UNICEF, Institut National de la Statistique, and Ministère du Développement et de la Coopération Internationale, Tunisie: Suivi de la situation des enfants et des femmes, enquête par grappes multiples 2011–2012 (New York: UNICEF, 2013), pp. 75–82.

- WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank,and United Nations Population Division MaternalMortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group, Maternal mortality in 1990–2013 (Geneva: WHO, 2014).

- Association Tunisienne des Femmes Démocrates and Coalition “EqualitywithoutReservation,”Les droits des femmes en Tunisie Déclaration (Tunis: Association Tunisienne des Femmes Démocrates, 2010), p. 7.

- I. Merali, “Advancing women’s reproductive and sexual health rights: Using the international human rights system,”Development in Practice 10/5 (2000), pp. 609–624; R. J. Cook, “International human rights and women’s reproductive health,” Studies in Family Planning 24/2 (1993), pp. 73–86; W. Nowicka, “Sexual and reproductive rights and the human rights agenda: Controversial and contested,” Reproductive Health Matters, 19 (2011), pp. 119–128.

- Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development, UN Doc.A/CONF.171/13 (1994).

- UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000)

- V. K. Pillai and R. Gupta, “Reproductive rights approach to reproductive health in developing countries,” Global Health Action 4 (2011), pp. 1–11; R. Connell, “Gender, health and theory: Conceptualizing the issue, in local and world perspective,” Social Science & Medicine 74/11 (2012), pp. 1675–1683.

- G.Sen and A. Mukherjee, “No Empowerment without rights, no rights without politics: Gender-equality, MDGs and the post-2015 development agenda,”Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 15/2–3 (2014), pp. 188–202; A. E. Yamin, “Defining questions: Situating issues of power in the formulation of a right to health under international law,” The Johns Hopkins University Press 18/2 (1996), pp. 398–438.

- Yamin (see note 12).

- K. R. Culwell, M. Vekemans, U. de Silva et al., “Critical gaps in universal access to reproductive health: Contraception and prevention of unsafe abortion,” International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 110 (2010), pp. S13–16; T. N. Thomas, J. Gausman, S. R. Lattof, et al., “Improved maternal health since the ICPD: 20 years of progress,” Contraception 90/6 (2014), pp. S32–S38.

- Pillai and Gupta (see note 11).

- Institut National de la Statistique, Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitat 2014: Principaux indicateurs (Tunis: Institut National de la Statistique, 2015), pp. 6–12.

- World Bank, The unfinished revolutions: Bringing opportunity, good jobs and greater wealth to all Tunisians (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2014 ), pp. 282–295.

- A. Khalil, “Tunisia’s women: Partners in revolution,” The Journal of North African Studies 2/19 (2014), pp. 186–199.

- Aim for Human Rights, Health rights of women assessment instrument (Utrecht: Aim for Human Rights, 2010).

- Ibid.

- L. Forman and G. MacNaughton, “Moving theory into practice: Human rights impact assessment of intellectual property rights in trade agreements,” Journal of Human Rights Practice 7 (2015), pp. 109–138; Minvielle and I. Goicolea, “Women’s right to health in the Anglo-Caribbean: Intimate partner violence, abortion and the state,” Feminismo/s. 18 (2011), pp. 93–112.

- Minvielle and Goicolea (see note 21); I. Goicolea, M. San Sebastian, and M. Wulff, “Women’s reproductive rights in the Amazon basin of Ecuador: Challenges for transforming policy into practice,” Health and Human Rights 10/91 (2008), pp. 91–

- G. Wang and V. Pillai, “Women’s reproductive health: A gender-sensitive human rights approach,” Acta Sociologican 44/3 (2001), pp. 231–242.

- Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development (see note 9).

- UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see note 10).

- R. Gataa, “Women’s empowerment and reproductive health,” in Experiences in Addressing Population and Reproductive Health Challenges (New York: United Nations Development Programme, 2011), pp. 221–227; Tunisian Penal Code (2013).

- H. Selma, “L’expérience tunisienne et l’évolution des services de l’avortement et PF depuis 1965” (presentation at Recontre sur l’avortement médicamenteux, ATDS STGO, Gammarth, Tunisia, 2011).

- UNICEF et al. (see note 5).

- Ministère de la Santé, Direction de Santé, Plan pour la lutte contre le cancer 2015–2019 (Tunis: Ministère de la Santé, 2015).

- Ministère de la Santé, Direction de Santé de Base, Rapport d’activité sur la riposte au Sida-Tunisie 2012–2013 (Tunis: Ministère de la Santé, 2014).

- Ministère de la Santé, Direction de Santé de Base, Suivi de la déclaration d’engagement sur le SIDA/VIH: Rapport de la Tunisie 2005–2007 (Tunis: Ministère de la Santé, 2008).

- UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (see note 1).

- Tunisian Personal Status Code (2014).

- Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development (see note 9); Platform for Action of the Fourth World Conference on Women, UN Doc. A/CONF.177/20 (1995).

- A. Germain, Sen, C. Garcia-Moreno, et al., “Advancing sexual and reproductive health and rights in low- and middle-income countries: Implications for the post-2015 global development agenda,” Global Public Health 10/2 (2015), pp. 137–148.

- G. Sen, “Sexual and reproductive health and rights in the post-2015 development agenda,” Global Public Health 9/6 (2014), pp. 599–606.

- UNFPA, Final country programmes document for Tunisia (New York: UNFPA, 2014).

- WHO, Countries: Tunisia. Available at http://www.who.int/countries/tun/en.

- Ministère de la Santé, Direction de la Santé et de la Planification, Carte sanitaire 2011 (Tunis: Ministère de la Santé, May 2013).

- WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, Country cooperation strategy for WHO and Tunisia 2010–2014 (Cairo: WHO, 2010).

- UNFPA (see note 37).

- R. Ben Aissa, “Apport du programme de PF/SR pour le bien-être de la famille tunisienne” (presentation at Journée nationale de la famille, December 11, 2013).

- Ibid.; Office National de la Famille et de la Population (see note 3); Mtiraoui and N. Gueddana, “The family and reproductive health program in underprivileged areas in Tunisia” (presentation at CICRED Seminar, Bangkok, November 25, 2002).

- United Nations and Republique tunisienne, Objectifs Millénaires pour le Développement: Rapport national de suivi 2013 (2014), pp. 102–

- E. Farhat, M. Chaoucha, H. Chelli, et al., “Reduced maternal mortality in Tunisia and voluntary commitment to gender-related concerns,” International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 116 (2012), pp. 165–168.

- United Nation and Republique tunisienne (see note 44).

- R. Dellagi, B. Souha, B. Salah Fayçal, et al., “L’enquête nationale tunisienne sur la mortalité maternelle de 2010: A propos des données de tunis,” La Tunisie Medicale 92/08–09 (2014), pp. 561–566.

- R. Dellagi, I. Belgacem, M. Hamrouni, et al., “Évaluation du système de suivi des décès maternels dans les structures publiques de Tunis (1999–2004),” Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 14/6 (2008), p. 1381.

- Legros and F. Chaoui, “Les systèmes de santé en Algérie, Maroc et Tunisie, Défis nationaux et enjeux partagés,” Les notes IPEMED, études et analyses 13 (2012), pp. 101-116. 50. Ibid.; T. Ensor and J. Ronoh, “Impact of organizational change on the delivery of reproductive services: A review of the literature,” International Journal of Health Planning and Management 20/3 (2005), pp. 209–225.

- S. Nair, Sexton, and P. Kirbat, “A decade after Cairo: Women’s health in a free market economy,” Indian Journal of Gender Studies 13/2 (2006), pp. 171–193.

- Ibid.

- V. Sánchez, Assessing development strategies to achieve the MDGs in the Republic of Tunisia (New York: United Nations Department for Economic and Social Affairs, 2011), p. 18.

- Mahjoub, “Economic, social and cultural rights in Tunisia: An assessment,” Mediterranean Politics 9/3 (2004), pp. 489–514.

- Office National de la Famille et de la Population, Ligue des Etats Arabes Projet Panarabe de la Santé de la Famille, Enquête tunisienne sur la santé de famille (Tunis:Panarab Project for Family Health, 2002), p.

- C. Gerdts, DePiñeres, S. Hajri, et al., “Denial of abortion in legal settings,” Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care (2014), pp. 1–3.

- WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (see note 40).

- Foster, J. El Haddad, and Z.Mhirzi, “Availability and accessibility of emergency contraception in postrevolution Tunisia,” Contraception 90/3 (2014), p. 337.

- Culwell et al. (see note 14).

- H. Chekir, “Women, the law, and the family in Tunisia,” Gender and Development 4/2 (1996), pp. 43–

- Gataa (see note 26); A. Grami, “Gender equality in Tunisia,” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 3/35 (2008), pp. 349–3

- Chekir (see note 60); Grami (see note 61).

- Gataa (see note 26); United Nations and Republique tunisienne (see note 44).

- United Nations and Republique tunisienne (see note 44).

- Institut National de la Statistique. Available at http://www.ins.tn/indexfr.php.

- Grami (see note 61).

- Office National de la Famille et de la Population and Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo, Enquête nationale sur la violence à l’égard des femmes. Rapport d’enquête (Tunis: Office National de la Famille et de la Population, 2010).

- Institut National de la Statistique (see note 16).

- Institut National de la Statistique. Available at: http://www.ins.tn/indexfr.php.

- Gataa (see note 26); C. Oueslati-Porter, “Infitah and (in)dependence: Bizerte women’s economic strategies three decades into Tunisian neoliberal policy,” Journal of North African Studies 18/1 (2013), pp. 141–158; UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (see note 1).

- Oueslati-Porter (see note 70).

- UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (see note 1); Assemblée des représentants du peuple, Sex repartition. Available at http://www.arp.tn/site/main/AR/docs/composition/compos_s.jsp.

- Grami (see note 61).

- CREDIF, “Femmes et élections: Les femmes peuvent-elles faire la difference?,” Revue du CREDIF 48 (2014), pp. 9-13. Available at: http://www.credif.org.tn/images/livres/2-Revue du CREDIF 48 FR.pdf.75. I. Zahoueni Lahouimel, “L’approche genre en Tunisie: Consolidation de l’égalité entre les femmes et les hommes” (presentation at 4ème Réunion de la Commission de l’égalité entre les femmes et les hommes, Strasbourg, November 13, 2013).

- UN Human Rights Council, Report of the working group on the issue of discrimination against women in law and in practice, UN Doc. A/HRC/23/50/Ad (2013).

- Pillai and Gupta (see note 11).

- Ibid.

- Khalil (see note 18).

- Oueslati-Porter (see note 70).

- Grami (see note 61); Chekir (see note 60).

- Gribaa and G. Depaoli, Profil genre en Tunisie 2014 (2014), p. 17. Available at http://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/tunisia/documents/page_content/profil_genre_tunisie2014_longue_fr.pdf.

- P. Ilkkaracan, “Commentary: Sexual health and human rights in the Middle East and North Africa: Progress or backlash?,” Global Public Health 10/2 (2015), pp. 268–270.