Corinne Schwarz, Erik Unruh, Katie Cronin, Sarah Evans-Simpson, Hannah Britton, and Megha Ramaswamy

Health and Human Rights 18/1

Published June 2016

Abstract

The medical sector presents a unique opportunity for identification and service to victims of human trafficking. In this article, we describe local and site-specific efforts to develop an intervention tool to be used in an urban hospital’s emergency department in the midwestern United States. In the development of our tool, we focused on both identification and intervention to assist trafficked persons, through a largely collaborative process in which we engaged local stakeholders for developing site-specific points of intervention. In the process of developing our intervention, we highlight the importance of using existing resources and services in a specific community to address critical gaps in coverage for trafficked persons. For example, we focus on those who are victims of labor trafficking, in addition to those who are victims of sex trafficking. We offer a framework informed by rights-based approaches to anti-trafficking efforts that addresses the practical challenges of human trafficking victim identification while simultaneously working to provide resources and disseminate services to those victims.

Introduction

Human trafficking is a global human rights concern impacting unknown numbers of people worldwide. Due to the stigma and criminalization associated with trafficking, it is empirically challenging to measure how many trafficked persons are subject to fraud, force, and exploitation, so researchers must rely on estimates. The International Labour Organization estimates that 20.9 million people are trafficked internationally each year.1 Within the US, the State Department estimates approximately 44,000 trafficked persons were identified and assisted in 2014.2 Even with these vast numbers—estimates that certainly do not account for all trafficked persons—there are limited trafficking-specific resources and intervention models. In the United States, anti-trafficking efforts are centered on prevention, protection, and prosecution, commonly referred to as the “Three Ps,” codified in the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA).3 This approach is consistent with global standards established by the United Nations Palermo Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, which emphasizes the importance of protecting survivors’ “internationally recognized human rights” as part of the Three Ps.4

Although the initial content of the TVPA and the Palermo Protocol was located within a criminal law framework, many countries and international anti-trafficking groups have attempted to pursue a more human rights-based approach (HRBA). On a basic level, this approach acknowledges that “Every person, regardless of their socioeconomic status, has the right to live a life free of slavery and abuse.”5 An individual’s identity, social status, or circumstances have no bearing on their right to avoid the exploitation and trauma of human trafficking. Furthermore, states have an obligation to protect this right, including for its most marginalized or vulnerable citizens.

Recognizing that the slavery, exploitation, and violence associated with trafficking are human rights violations, the implementation of many anti-trafficking programs and policies attempts to find ways for rights to be asserted and protected. Since all national governments are able to assert that slavery and trafficking are repugnant, passing national anti-trafficking legislation is a clear way to assert their alignment with international human rights norms, as well as to establish their national legitimacy as modern states.6

Despite the fact that protection, prevention, and prosecution are frequently mobilized as equally important components to domestic anti-trafficking work, they are disproportionately funded and emphasized. Many current models use only a judicial framework to target human traffickers “while human rights and social change are much harder to legislate.”7 Even when anti-trafficking models take a victim-centered approach—which nominally seeks to privilege survivors’ rights and agency—it is easy to return to the carceral state’s quantifiable outcomes of arrests and successful prosecutions.8 While prosecution is necessary, it occurs after the initial trauma and violence of trafficking has already taken place. Prevention—addressing the root causes of human trafficking and expanding access to economic and social rights to prevent its occurrence—remains a critically important yet challenging component of anti-trafficking advocacy.9 Prevention and protection approaches are more in line with an HRBA to trafficking, as these efforts can emphasize the state’s obligations to ensure individuals have the continued ability to live a life free from exploitation.10

The medical sector is a valuable site for anti-trafficking interventions focused on protection, prevention, and specifically for interventions focused on protecting an individual’s right to access health services. Studies estimate that anywhere from 30-87.8% of trafficked persons access medical services at some point during their exploitation.11 Trafficked persons are not an entirely hidden population, but medical professionals must be equipped with education, intervention tools, and active social service partnerships in order to assist these vulnerable patients. Using an HRBA within the medical sector to address human trafficking centers on these hidden populations—and their unique health outcomes—that might otherwise be ignored or excluded within health care service dissemination.12

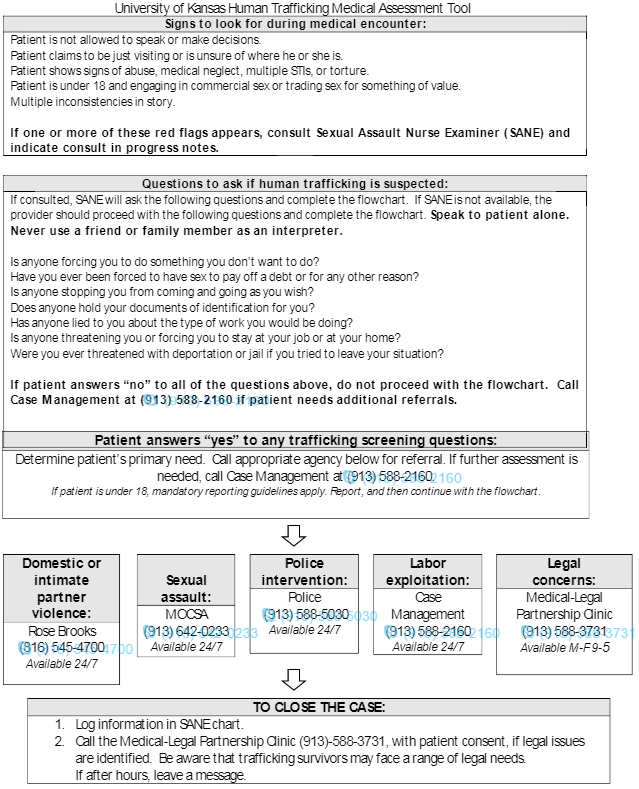

This article explores our experiences developing an intervention tool—a flowchart based on an existing practice guideline—in the emergency department at the University of Kansas (KU) Hospital. The prevailing framework for developing intervention tools stops at the point of identifying victims and survivors, and thus falls short at providing services, especially site-specific services that can address the structural inequities and vulnerabilities that trafficked persons face. Our flowchart (Figure 1) unites identification and intervention to assist trafficked persons from their entrance in the emergency room to their exit from the hospital. Based on this collaborative process, we believe anti-trafficking interventions require outreach with key community partners, especially those in the social service sector. Our team of students, professors, and medical professionals developed a human trafficking identification flowchart that prioritizes trafficked persons’ right to health services and engages community partners with trafficking-specific resources. This joint endeavour between researchers and practitioners resulted in an intervention that addresses the Three Ps framework, unites anti-trafficking theory with praxis, and forges meaningful connections across anti-trafficking allies in the Kansas City community. The findings of this process also point to the importance of developing site-specific identification and intervention models that utilize the existing resources and services in a community and address critical gaps in coverage for trafficked persons.

Trafficking risk factors and red flags

Common human trafficking risk factors—characteristics or inequities that push people toward trafficking—include poverty, lack of education, English language limitations, LGBTQ status, gender inequality, addiction, housing insecurity or homelessness, political unrest or war, and early childhood trauma or abuse.13 It is important to remember that the presence of these risk factors does not automatically mean that trafficking will occur. For example, someone can live in poverty without becoming trafficked. Rather, it is the increased presence of multiple risk factors that push people towards exploitation and trafficking. When people are disenfranchised along multiple axes—where many structural inequalities converge—their risk of trafficking increases.14

Trafficking red flags are different from risk factors. While risk factors make people vulnerable to trafficking, red flags indicate that trafficking may have occurred or may be ongoing. Common red flags include specific health presentations, including untreated sexually transmitted infections (STIs) or “on-the-job” injuries; patients accompanied by a controlling person, such as a partner, family member, or employer; patients who are unsure of their location; or patients lacking personal documents or identification.15 The presence of red flags should trigger interventions; however, the lack of widespread training across all sectors creates a gap between the presence of red flags, their recognition as signs of trafficking, and intervention by medical professionals.

Trafficked persons access the medical sector for a variety of different health presentations, including STIs, physical injuries, burns, anxiety, PTSD, suicidal ideation, complications from unsafe abortions, substance abuse, HIV/AIDS, depression, sexual violence, malnutrition, skin conditions, gastrointestinal disorders, dental injuries and diseases, and tuberculosis.16 Though physical health outcomes are the most recognized and documented, trafficked persons’ “mental health is perhaps the most dominant health dimension […] because of the profound psychological damage caused by (often chronic) traumatic events and the common somatic complaints that frequently translate into physical pain or dysfunction.”17

Professionals in the medical sector are in a unique position to identify these red flags and treat these health presentations. Though trafficked persons are perceived to be a hidden population due to the illicit nature of trafficking as a criminal activity, as stated earlier, studies now show that a substantial portion of trafficked persons encounter the medical sector to some degree.18 These interactions are not limited to one medical setting; trafficked persons may enter the medical sector through hospitals, emergency rooms, private physicians, or clinical treatment facilities.19

Additionally, some studies have shown that “trafficking victims are more likely to talk to medical staff than police.”20 Thus, the presence of trafficking red flags could be an ideal intervention point to trigger identification and services. However, “identification of possible victims is difficult […] because victims seldom self-identify, and clinically validated screening tools for the health care setting are lacking.”21 Even if victims do name their experiences as human trafficking, doctors might not understand the complexity or danger of their situation.22 Though a variety of health professional organizations have released statements regarding education on human trafficking—including the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists, the American Medical Association Medical Student Section, the Christian Medical and Dental Associations, and the American Academy of Pediatrics—there is still no standardized, “formal, evidence-based curricula” for medical professionals.23

The need for this level of training is particularly high among medical professionals working in emergency rooms. These personnel who “often care for the disenfranchised are far more likely than the general population to interact with trafficking victims.”24 One study of sex trafficking survivors found that 63.3% of their survey respondents went to a hospital emergency room for services.25 The patients who visit emergency department personnel are likely to be in particularly vulnerable situations; expanding their screening processes to encompass exploited and trafficked persons is a useful first step for ensuring individuals’ rights to health services and protection from exploitation.

Developing anti-trafficking interventions

The KU School of Law’s Medical-Legal Partnership Clinic (MLP Clinic) works with medical professionals to provide free legal services to low-income patients at the KU Hospital and Physicians clinics. In 2013, MLP Clinic staff and students participated in the Kansas Conference on Slavery and Human Trafficking and helped to form the advocacy arm of KU’s Anti-Slavery and Human Trafficking Initiative (ASHTI). The MLP Clinic expanded the legal services it provided to patients to address the specific legal remedies available to survivors of human trafficking. Recognizing the important role the MLP Clinic could play in training medical providers to recognize the red flags of human trafficking and connect victims to services, the MLP Clinic partnered with the School of Medicine’s Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine to assist in the development of a screening guideline that could be used by medical professionals and staff in the KU Emergency Department (ED).

A context-specific guideline was developed for providers at the KU ED using concepts of the most recent protocols and recommendations from multiple field experts.26 In addition, multiple institutional representatives provided feedback on the development of the guideline, including physicians, nurse managers, social work representatives, Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANE), and partners in the MLP Clinic and Department of Public Health and Preventative Medicine. Given the organizational structure of the KU ED, the developers of the guideline aimed to mobilize a nursing committee to help champion and “own” the implementation of the guideline.

Since the SANE team and its constituents were trained to handle highly sensitive patient encounters while being strict observers of legal evidence, it was evident that the SANE team was the appropriate vehicle to implement the guideline. The SANE team has been specifically trained to work with survivors of sexual violence. With this training, they are also instructed in interviewing these patients. During the SANE training, nurses are taught to look for the red flags for sexual violence, domestic violence, and human trafficking. A SANE is also knowledgeable in forensic matters. As a part of the SANE team, the nurse has further education on how to take care of a patient and maintain forensic evidence. This is helpful in many human trafficking cases. Once the guideline had been finalized, a representative from the ED presented the guideline to the hospital’s Guideline and Protocol Committee. Upon approval, it immediately became effective and was available through the hospital’s intranet for reference. Additionally, both the SANE team and the ED were trained on the guideline. The ED was given the red flags and warning signs and instructed to call the SANE team. The SANE team was given the resources and refreshed on the warning signs and how to best speak with these patients.

To facilitate use of the screening guideline, graduate students in the Department of Public Health and Preventative Medicine developed a flowchart model (Figure 1) for an intervention tool based on the Polaris Project Medical Assessment Tool, which has been widely advocated for use in the US for human trafficking screening in health care settings.27 The Medical Assessment Tool is an ideal screening tool as it is “structured as an algorithm similar to many other medical decision-making tools, which facilitates its application” and requires a “low initial time investment” to learn.28

This model provides a series of questions; as medical providers answer yes or no, they are directed to different wings of the chart with different resources. We used the Medical Assessment Tool as a model for our next phase of work and included Kansas City specific-resources for ED staff.

Best practices for guideline development and community engagement

Our intervention tool is unique to the KU ED. Since studies have shown that the emergency room is the most common site of medical intervention for trafficked persons, it is a logical site to introduce anti-trafficking interventions.29 However, we recognize that other medical sites can facilitate anti-trafficking interventions: family planning clinics, public clinics, private medical offices, and urgent care centers.30 Regardless of the medical setting, developers must be ready to work with medical administrators at the institutional level and community stakeholders at the local level in order to fully implement an anti-trafficking intervention. In development of a screening guideline, protocol, or flowchart, we found that it was important to engage with all professionals and departments that were referenced in those tools and would be called upon to provide services to potential victims of human trafficking. These conversations helped clarify roles, surface other policies that may be implicated (including existing mandatory reporting policies that may be triggered by the abuse or neglect of minor patients), and develop buy-in from key stakeholders.

Engagement with institutional partners

Even if an intervention tool is isolated to one medical setting—in our case, an emergency department in a research hospital—developers must attempt to engage administrators within and outside this specific setting. Gaining administrative support for an anti-trafficking intervention helps developers gain credibility and access, especially when dealing with implementation outside a familiar department.

Although our intervention was designed for a single department, it spans many medical departments and incorporates many local service providers. Significant steps were taken to collaborate across disciplines within KU, including allowing different departmental representatives access to draft versions of the guideline and developing multidisciplinary trainings. A department-specific training was incorporated into staff meetings to train staff regarding the guideline. In addition, a community-wide training aimed at health care providers, social workers, and law enforcement officials was held to raise awareness and to foster an environment of collaboration across disciplines. This training is now being developed into an annual event.

Even following passage of a screening guideline or protocol, significant additional steps must be taken to encourage its use. At the KU Hospital, a small task force made up of the MLP Clinic and Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine faculty and students, ED staff, and the SANE Coordinator for the hospital are meeting regularly to plan events and trainings to raise awareness of human trafficking, generally, and to encourage use of the guideline and flowchart.

Locating community stakeholders

A comprehensive medical anti-trafficking intervention looks beyond patient intake and treatment of presentations to answer the question: what happens when a trafficked person gets discharged? The medical sector is in a unique position to serve as an intermediary between trafficked patients and community resources, especially those provided in the social service sector. Groups that provide shelter, meals, and therapeutic or rehabilitative services provide the protection required under the Three Ps framework, and interventions must be able to readily mobilize these resources when trafficked patients are discharged from the hospital.

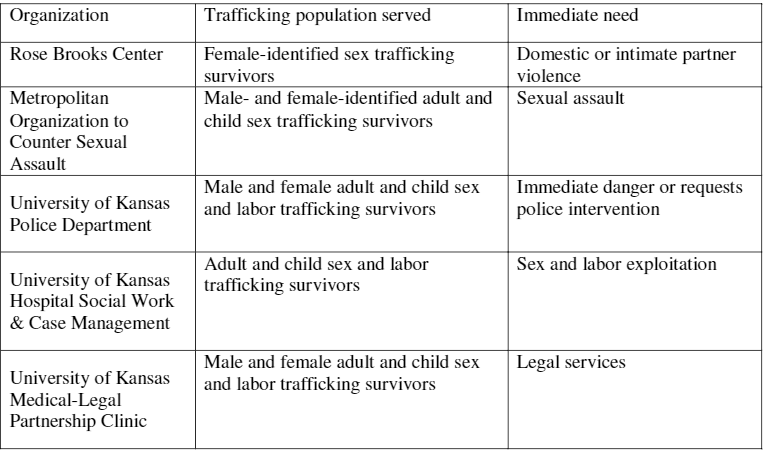

In order to create a site-specific HRBA intervention, developers must find key community stakeholders in a variety of sectors—law enforcement, social service, and legal—who are already equipped to assist trafficked persons. As it is critical “to ensure the participation of affected communities in the design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of programs and interventions,” we used a two-pronged approach to directly locate and communicate with community stakeholders.31 During this process, we simultaneously determined which resources were most useful for trafficked persons and which community stakeholders could provide those resources. Since our flowchart identified both sex and labor trafficking, we agreed that it was necessary to provide resources to assist both sets of survivors. While preparing the flowchart, graduate students in a Master of Public Health course on human trafficking located community stakeholders through an organizational scan of relevant Kansas City-area services as part of a semester-long service-oriented group project.32 After comparing this list to the human trafficking practice guideline approved by the KU Hospital—which identified many of the same stakeholders—students conducted semi-structured interviews with staffers at these organizations. Interviews addressed which trafficked populations these groups serve; what services they offer; and what tools they use to identify and assist trafficked persons. These interviews allowed students to see if organizations had tools in place for identification of sex and labor trafficking survivors; if they were trained to specifically work with trafficked populations; and if they were part of a larger network of social service providers who work in a formal anti-trafficking coalition in the Kansas City metropolitan area.

Some community stakeholders were invested in anti-trafficking efforts but only had services in place for female-identified survivors. Other stakeholders held strict office hours and would be unavailable to assist survivors who were identified outside of typical work hours. These were critical pieces of information that were only discovered through the interview process. After conducting interviews with seven organizations, students determined that five resource-stakeholder partnerships logically emerged from the findings.

Table 1: Resource-Stakeholder Partnerships

Given the desire to localize services for survivors, our team decided to prioritize immediate intervention partners and state hotlines for identification and protection on the flowchart. Our team agreed to work first with the most immediate points of contact (law enforcement, shelters, legal services) to limit possible re-traumatization and to ensure swift action. We incorporated information on national resources in all trainings and workshops, and would inform all patients of national resources as well. We viewed our flowchart as a living document to be regularly evaluated and revised according to the needs of our specific patient population and available services. The addition of our flowchart to the original practice guideline approved by the KU Hospital represents such a re-evaluation of needs and services.

Considerations for identification of victims

Developers must determine their framework for identification and resource distribution: is it meaningful to identify trafficked persons if there are no resources in place to provide to them? Do identification models allow survivors to exercise their right to access services and resources, or do they further constrain their agency? We believe that anti-trafficking interventions should be relational. When a person discloses or is identified as a trafficked person, this should result in the dissemination of resources—the flowchart needs to conclude with assistance. We are also fortunate that we live in a community with some resources available to address human trafficking. However, even in the Kansas City metro area, we struggled with how to engage the vulnerable population of labor trafficking survivors without further denying them their right to health services, re-traumatizing them through multiple disclosures, or directing them to services that could not prioritize their immediate needs.

As stated above, our flowchart identified sex and labor trafficking, creating the need to provide resources to both sets of survivors. However, the Kansas City metro area does not have many resources in place to combat labor exploitation. The Kansas City resource gap is not unique. Labor trafficking is generally more underreported than sex trafficking across the US, and the federal-level focus on sex trafficking and on deporting undocumented migrants renders many labor trafficking survivors invisible or ineligible for services.33 In order to close this gap in our flowchart and maintain resources for labor trafficking survivors, we began a conversation with the KU Hospital Social Work & Case Management Department. This department serves the ED by providing social services to patients in the emergency room.

Through several conversations, we learned that Social Work & Case Management can perform a “social admit” for ED patients. A social admit is for patients whose health has improved—leading to discharge from the ED—but whose social circumstances necessitate an overnight stay. For labor trafficking survivors who cannot access the same resources as sex trafficking survivors, this social admit may be crucial. It provides incredibly vulnerable patients extra time to determine a course of action with the help of KU Hospital social workers trained to work with ED patients. This accommodation for vulnerable patients would not have been realized without ongoing communication between the research team, ED staffers, and the KU Hospital Social Work & Case Management Department, emphasizing the importance of collaborative anti-trafficking efforts within the medical sector.

Communities that do not have an adequate resource infrastructure should not necessarily see this gap as incompatible with developing an anti-trafficking intervention. Rather, we suggest that communities build upon what relationships and resources they have in order to create a successful intervention that prioritizes trafficked persons’ rights and expands access to services that address their immediate needs. For example, if developing interventions for a community that does not have a domestic violence shelter within city limits, it might not be best to develop a protocol that directs people to shelter services. Instead, it might be more feasible to look for alternative pathways to providing shelter within the community—like social admits within the local hospital—or outside the community—for example, pursuing a relationship with a domestic violence shelter that serves the county or a neighboring community. If these pathways do not prove fruitful—if no resources can be delivered through following that arm of the flowchart to its conclusion—then developers must consider the implications of including it as part of an anti-trafficking intervention.

Conclusion

The literature on the medical sector’s response to human trafficking is starting to emerge, outlining both the need and opportunity for identification of victims of human trafficking.34 There is also significant activity outside of the scholarly literature, including coverage in the press, as well as groups organizing to better understand and address the problem of human trafficking identification in the medical sector.35 Having an HRBA to trafficking within the medical sector is focused on ensuring that states and communities meet their obligations to protect individuals from trafficking and to interrupt exploitation as it is happening. Beyond just identifying trafficked persons, identification tools that are built within an HRBA framework must then ensure individuals are immediately linked to accessible services, institutions, and programs that can prevent future exploitation.

What we see thus far, however, is a dearth of information about what happens after victims of trafficking are identified in health care settings.36 Much work still needs to be done in formalizing protocols that specifically address service provision beyond identification of trafficking victims. Coordinated and local responses are likely to work best in serving vulnerable patient populations. Indeed, front-line providers understand the limitations of what they can do in social service, legal, and health care settings, as well as appreciate the need for greater resources.37 Our work has also highlighted the need for an increased emphasis in the literature and increase in the services available to victims of labor exploitation, beyond victims of sexual labor exploitation, exclusively. Future work must underscore the full spectrum of needs of all trafficking victims, as well as provide frameworks for how to address those needs beyond identification.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following students in the KU Master of Public Health course on human trafficking for their help with reaching out to institutional and community partners and drafting the KU ED human trafficking medical assessment flowchart: Jessica Wearing, Emma Austenfeld, Michelle Nguyen, Stephen Valliere, and Anne Nzuki.

Figure 1: Human Trafficking Medical Assessment Flowchart

Corinne Schwarz is PhD Candidate, Department of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA.

Erik Unruh, BSN, MPH, is Medical Student , University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City, KS, USA.

Katie Cronin is Pro Bono Manager, Stinson Leonard Street LLP, Kansas City, MO, USA.

Sarah Evans-Simpson is SANE Coordinator, University of Kansas Hospital Emergency Department, Kansas City, KS, USA.

Hannah Britton is Associate Professor of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and Political Science, Department of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and Department of Political Science, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA.

Megha Ramaswamy is Associate Professor of Preventive Medicine & Public Health, Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City, KS, USA.

Please address correspondence to the authors c/o Corinne Schwarz, 318 Blake Hall, 1541 Lilac Lane, Lawrence, KS 66045, USA. Email: cschwarz@ku.edu.

References

- International Labour Organization, Forced labour, human trafficking and slavery (2012). Available at http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/forced-labour/lang–en/index.htm.

- US Department of State, Trafficking in Persons Report June 2014. (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of State, 2014). Available at http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/226844.pdf.

- Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, The 3Ps: Prevention, Protection, Prosecution. (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of State, 2011). Available at http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/167334.pdf.

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. (2000). Available at http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/ProtocolTraffickingInPersons.aspx.

- K. McGregor Perry and L. McEwing, “How do social determinants affect human trafficking in Southeast Asia, and what can we do about it? A systematic review,” Health and Human Rights 15/2 (2013), pp. 138-159.

- H. Britton and L. Dean, “Policy responses to human trafficking in Southern Africa: Domesticating international norms,” Human Rights Review 15/3 (2014), pp. 305-328; J. Goodey, “Human trafficking: Sketchy data and policy responses,” Criminology & Criminal Justice 8/4 (2008), pp. 421-442.

- Britton and Dean (see note 6).

- J. Todres, “A child rights framework for addressing trafficking of children,” Michigan State International Law Review 22/2 (2014), pp. 557-594.

- A. Duger, “Focusing on prevention: The social and economic rights of children vulnerable to sex trafficking,” Health and Human Rights 17/1 (2015), pp. 114-123; Goodey (see note 6); N. Lindstrom, “Transnational responses to human trafficking in the Balkans,” International Affairs Working Paper 9 (2006), pp. 1-22; J. Todres, “Moving upstream: The merits of a public health law approach to human trafficking,” North Carolina Law Review 89 (2011), pp. 447-506.

- G. Danailova-Trainor and F. Laczko, “Trafficking in persons and development: Towards greater policy coherence,” International Migration 48/4 (2010), pp. 38-83.

- S.B. Baldwin, D.P. Eisenman, J.N. Sayles, G. Ryan, and K.S. Chuang, “Identification of human trafficking victims in health care settings,” Health and Human Rights 13/1 (2011), pp. 36-49; H.J. Becker and K. Bechtel, “Recognizing victims of human trafficking in the pediatric emergency department,” Pediatric Emergency Care 31/2 (2015), pp. 144-150; Family Violence Prevention Fund, Turning pain into power: Trafficking survivors’ perspectives on early intervention strategies. (San Francisco: Family Violence Prevention Fund, 2005); L.J. Lederer and C.A. Wetzel, “The health consequences for sex trafficking and their implications for identifying victims in healthcare facilities,” Annals of Health Law 23 (2014), pp. 61-91.

- M. Unnithan, “What constitutes evidence in human rights-based approaches to health? Learning from lived experiences of maternal and sexual reproductive health,” Health and Human Rights 17/2 (2015), pp. 45-56.

- W. Macias Konstantopoulos, R. Ahn, E.J. Alpert, et al., “An international comparative public health analysis of sex trafficking of women and girls in eight cities: Achieving a more effective health sector response,” Journal of Urban Health 90/6 (2013), pp. 1194-1204; C. Schwarz and H. Britton, “Queering the support for trafficked persons: LGBTQ communities and human trafficking in the heartland,” Social Inclusion 3/1 (2015), pp. 63-75; C. Zimmerman, M. Hossain, and C. Watts, “Human trafficking and health: A conceptual model to inform policy, intervention and research,” Social Science & Medicine 73 (2011), pp. 327-335.

- McGregor Perry and Ewing (see note 5).

- N.A. Deshpande and N.M. Nour, “Sex trafficking of women and girls,” Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology 6/1 (2013), pp. e22-e27; M.G. O’Callaghan, “The health care professional as a modern abolitionist,” The Permanente Journal 16/2 (2012), pp. 67-69; R.B. Patel, R. Ahn, and T.F. Burke, “Human trafficking in the emergency department,” Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 11/5 (2010), pp. 402-404; Polaris Project, Comprehensive Human Trafficking Assessment. (Washington, D.C.: Polaris Project, National Human Trafficking Resource Center, 2001). Available at http://mspny.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Trafficking-Assessment.pdf.

- R. Ahn, E.J. Alpert, G. Purcell, et al., “Human trafficking: Review of educational resources for health professionals,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 44/3 (2013), pp. 283-289; Macias Konstantopoulos et al. 2013 (see note 13); O’Callaghan 2012 (see note 15).

- Zimmerman et al., pp. 331 (see note 13).

- Baldwin et al. (see note 11); Becker and Bechtel (see note 11); Family Violence Prevention Fund (see note 11); Lederer and Wetzel (see note 11).

- J. Greenbaum, J.E. Crawford-Jakubiak, and Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect, “Child sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: Health care needs of victims,” Pediatrics 135/3 (2015), pp. 1-9; Lederer and Wetzel (see note 11).

- N. Bespalova, J. Morgan, and J. Coverdale, “A pathway to freedom: An evaluation of screening tools for the identification of trafficking victims,” Academic Psychiatry (2014), pp. 1-5.

- Greenbaum et al., pp. 3 (see note 19).

- Lederer and Wetzel (see note 11).

- A.M. Grace, R. Ahn, and W. Macias Konstantopoulos, “Integrating curricula on human trafficking into medical education and residency training,” JAMA Pediatrics 168/9 (2014), pp. 793-794.

- Patel et al., pp. 402 (see note 15).

- Lederer and Wetzel, pp. 77 (see note 11).

- Center for the Human Rights of Children, Building Child Welfare Response to Child Trafficking. (Chicago: Loyola University Chicago, 2011). Available at http://www.luc.edu/media/lucedu/chrc/pdfs/BCWRHandbook2011.pdf; Connecticut Department of Children and Families, Practice Guide for Intake and Investigative Response To Human Trafficking of Children. (Hartford, CT: Connecticut Department of Children and Families, 2014). Available at http://www.ct.gov/dcf/lib/dcf/humantrafficing/pdf/human_trafficking_pg_-_copy.pdf; Covenant House, Homelessness, Survival Sex and Human Trafficking: As Experienced by the Youth of Covenant House New York (New York: Covenant House, 2013). Available at https://d28whvbyjonrpc.cloudfront.net/s3fs-public/attachments/Covenant-House-trafficking-study.pdf; Mount Sinai Emergency Medical Department, Human Trafficking Information and Resources for Emergency Healthcare Providers (New York: Mount Sinai Hospital, 2005). Available at http://www.humantraffickinged.com/index.html; Ohio Human Trafficking Task Force, Human Trafficking Screening Tool (Columbus, OH: Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, 2013). Available at http://mha.ohio.gov/Portals/0/assets/Initiatives/HumanTraficking/2013-human-traffricking-screening-tool.pdf; Polaris Project (2001, see note 15); Polaris Project, Medical Assessment Tool. (Washington, D.C.: Polaris Project, National Human Trafficking Resource Center, 2010). Available at http://www.safvic.org/content/uploads/safvic/documents/Resources%20-%20HT/Medical%20Assessment%20Tool%20-%20HT.pdf; Vera Institute of Justice, Screening for Human Trafficking (New York: Vera Institute of Justice, 2014). Available at http://www.vera.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/human-trafficking-identification-tool-and-user-guidelines.pdf; Via Christi Health, Human Trafficking Assessment for Clinicians. (Wichita, KS: Via Christi Health, 2015). Available at https://www.viachristi.org/sites/default/files/pdf/about_us/2015-0625%20Human%20trafficking%20assessment_web.pdf; L.M. Williams and M.E. Frederick, Pathways into and out of commercial sexual victimization of children: Understanding and responding to sexually exploited teens (Lowell, MA: University of Massachusetts—Lowell, 2009). Available at http://traffickingresourcecenter.org/sites/default/files/Williams%20Pathways%20Final%20Report%202006-MU-FX-0060%2010-31-09L.pdf; Wisconsin Statewide Human Trafficking Committee, Wisconsin Human Trafficking Protocol and Resource Manual (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Office of Justice Assistance, Violence Against Women Program, 2012). Available at http://www.endabusewi.org/sites/default/files/resources/Wisconsin%20Human%20Trafficking%20Protocol%20and%20Resource%20Manual.pdf.

- Polaris Project (2010, see note 26); U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, The Campaign to Rescue and Restore Victims of Human Trafficking: HHS Human Trafficking Order Form (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015). Available at http://archive.acf.hhs.gov/trafficking/about/form.htm; Via Christi (see note 26).

- Bespalova et al., pp. 4 (see note 20).

- Lederer and Wetzel (see note 11); Patel et al. (see note 15).

- Greenbaum et al. (see note 19); Lederer and Wetzel (see note 11).

- Unnithan, pp. 46 (see note 12).

- University of Kansas Institute for Social and Policy Research, Anti-Slavery and Human Trafficking Initiative: Teaching. (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas, 2014). Available at http://ipsr.ku.edu/ASHTI/teaching.html.

- J. Srikantiah, “Perfect victims and real survivors: The iconic victim in domestic human trafficking law,” Boston University Law Review 87 (2007), pp. 157-211.

- Baldwin et al. (see note 11); Becker and Bechtel (see note 11); Lederer and Wetzel (see note 11).

- HEAL Trafficking, Health Professional Education, Advocacy & Linkage. (2015). Available at https://healtrafficking.wordpress.com.

- M. Burke, H.L McCauley, H.L. Rackow, B. Orsini, B. Simunovic, and E. Miller, “Implementing a coordinated care model for sex-trafficked minors in smaller cities,” Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk 6/1 (2015), Article 7.

- W.L. Macias-Konstantopoulos, D. Munroe, G. Purcell, et al., “The commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the Boston metropolitan area: Experiences and challenges faced by front-line providers and other stakeholders,” Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk 6/1 (2015), Article 4.