Steven J. Hoffman and John-Arne Røttingen

Health and Human Rights 15/1

Published June 2013

Abstract

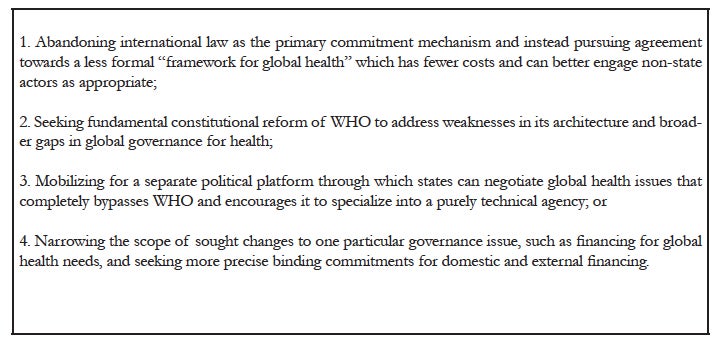

The costs of any proposal for new international law must be fully evaluated and compared with benefits and competing alternatives to ensure adoption will not create more problems than solutions. A systematic review of the research literature was conducted to categorize and assess limitations and unintended negative consequences associated with the proposed Framework Convention on Global Health (FCGH). A critical analysis then interpreted these findings using economic, ethical, legal, and political science perspectives. Of the 442 documents retrieved, nine met the inclusion criteria. Collectively, these documents highlighted that an FCGH could duplicate other efforts, lack feasibility, and have questionable impact. The critical analysis reveals that negative consequences can result from the FCGH’s proposed form of international law and proposed functions of influencing national budgets, realizing health rights and resetting global governance for health. These include the direct costs of international law, opportunity costs, reducing political dialogue by legalizing political interactions, petrifying principles that may have only contemporary relevance, imposing foreign values on less powerful countries, forcing externally defined goals on countries, prioritizing individual rights over population-wide well-being, further complicating global governance for health, weakening the World Health Organization (WHO), reducing participation opportunities for non-state actors, and offering sub-optimal solutions for global health challenges. Four options for revising the FCGH proposal are developed to address its weaknesses and strengthen its potential for impact. These include: 1) abandoning international law as the primary commitment mechanism and instead pursuing agreement towards a less formal “framework for global health”; 2) seeking fundamental constitutional reform of WHO to address gaps in global governance for health; 3) mobilizing for a separate political platform that completely bypasses WHO; or 4) narrowing the scope of sought changes to one particular governance issue such as financing for global health needs.

Introduction

The last 20 years have been a golden age for global health. Financial resources increased from $5.82 billion USD in 1990 to $28.2 billion USD in 2012, and results have been astounding.1 Child mortality has been cut by 41%, maternal mortality reduced by 47%, and the spread of HIV/AIDS, malaria and other infectious diseases is starting to reverse.2

But there are fundamental problems of global governance for health that threaten prospects for continued progress. These challenges range from insufficient resources, flawed priority-setting processes, and neglect of basic health needs, to lack of leadership, poor collaboration, and inadequate accountability.3 Various proposals have been put forward for better ways to make decisions, allocate funds, coordinate activities, and monitor achievements.4 Some call for transformative changes (e.g., Global Plan for Justice), while others suggest minor tweaks (e.g., Global Health Forum/Committee C).5 Some rely on existing structures (e.g., Biosecurity Concert), while others propose the creation of new entities (e.g., Global Fund for Health).6 Some seek to address many challenges facing the global health community at once (e.g., United Nations Global Health Panel), while still others focus on specific policy areas (e.g., Health Impact Fund).7

One particularly prominent proposal for reform, put forward by Georgetown University’s Lawrence Gostin, is the negotiation of a Framework Convention on Global Health (FCGH).8 This bold proposal calls for crafting a new international law and ancillary protocols that would articulate national and global responsibilities for health and set binding commitments. In many ways, its starting point is the fragmentation of the global health system and underperformance of the World Health Organization (WHO) and other mechanisms for global governance in this era of increasing regime complexity.9 The articulated goal of the FCGH proposal is to promote more generous health spending by governments for both domestic and external needs, to realize the human right to health by defining the content of universal health coverage, and to reset global governance arrangements for health through treaty and incremental protocol negotiations. The expected benefits of this proposal have been articulated in many journal articles, reports, and books, and espoused by a coalition of academics and civil society organizations involved in the Joint Action and Learning Initiative on National and Global Responsibilities for Health (JALI) as part of a worldwide advocacy campaign.10

Virtues of an FCGH are numerous and clear: the proposal has great transformative potential and represents a bold vision for reforming global governance for health. But in addition to expected benefits, proposals for reform should also be assessed for their potential costs, limitations, and unintended consequences, and should be compared with benefits and competing alternatives before they are implemented. As with any important decision, this helps to ensure both that the greatest impact is achieved with the resources available and that reforms do not create more problems than they solve. Primum non nocere or “first do no harm” is as relevant for national and global policymakers as it is for clinicians. Even the most seemingly virtuous proposals for reform deserve rigorous scrutiny, especially when something as important as global governance is implicated. For even the most noble and altruistic pursuits emblematic of virtuosity—like international human rights—have been shown by scholars, such as Harvard Law School’s David Kennedy, to have worrisome “dark sides” worthy of everyone’s close attention, such as exacerbating power imbalances, deepening inequalities, and undermining political contestation.11 Potential unintended dark sides of the FCGH proposal need to be identified, assessed, and mitigated, lest we fall prey to them.

This article reports on a systematic review of the research literature that sought to identify possible limitations of the FCGH proposal that may prevent achievement of expected benefits and potential unintended negative consequences that may result from the proposal’s implementation. A critical analysis of these findings and gaps in this literature is then developed along with four options for revising the FCGH proposal to address its weaknesses and enhance its potential for impact. Ultimately, it is hoped that this systematic review and critical analysis will serve to enrich current discussions on the potential merit of negotiating an FCGH, identify opportunities for strengthening the proposal for the future, and shed new light on how global governance reforms for health may be assessed by implementing a new methodological approach that combines elements from across disciplines and research traditions.

Methodology

A systematic review was conducted with structured searching to find all journal articles, lectures, reports, and working papers that discussed limitations and potential unintended negative consequences of the FCGH proposal. Findings were interpreted through thematic synthesis, a qualitative method that integrates the use of free coding, iterative categorization of text fragments, and reciprocal translational analysis from meta-ethnography with grounded theory’s inductive approach and constant comparison method.12Appraisal and weighting of documents by quality were not pursued due to the absence of any studies that used empirical methodologies.

Electronic searches were conducted from November 7-9, 2012, in Google Scholar (all years), International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (1951-2012), International Political Science Abstracts (1989-2012), Legal Trac (1980-2012), MEDLINE (OVID) (1966-2012), PAIS International (1972-2012), ProQuest Political Science (1985-2012), and Worldwide Political Science Abstracts (1975-2012), using the exact search term “Framework Convention on Global Health” OR “FCGH.” These searches yielded 442 retrieved documents for possible inclusion.

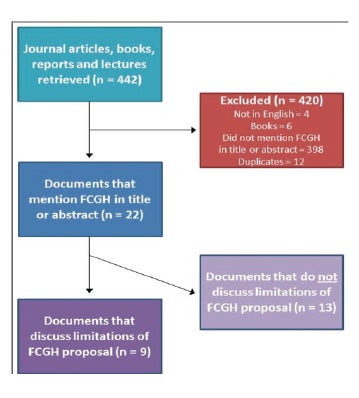

To be included in the systematic review, retrieved documents had to be 1) written in English, 2) published in any format other than a book, and 3) contain the exact term “Framework Convention on Global Health” or “FCGH” in their title or abstract. Applying these three inclusion/exclusion criteria and removing duplicates resulted in 22 unique documents (see Figure 1).13

Findings from the systematic review were then used as a starting point to inform a critical analysis of potential limitations and unintended negative consequences of the FCGH proposal based on economic, ethical, legal, and political science perspectives. The analysis probed implications of both the FCGH’s proposed form and its proposed functions.

Figure 1: Flow chart of the systematic review

Findings from the systematic review

Characteristics of the included documents

The 22 documents were mostly articles published in law journals (n=9) or health/medical journals (n=9). The rest were either government publications (n=1), student reports (n=2) or conference proceedings (n=1). The majority were authored or co-authored by the proposal’s progenitor (n=17).

Based on a full-text reading, nine of these 22 documents were found to include a sustained discussion of limitations associated with the FCGH proposal.14 The nine documents were mostly law journal articles (n=6); interestingly, the health/medical journal articles did not contain sustained discussions of limitations. No retrieved documents were found that discuss potential negative consequences of the FCGH proposal.

Identified limitations of the FCGH proposal

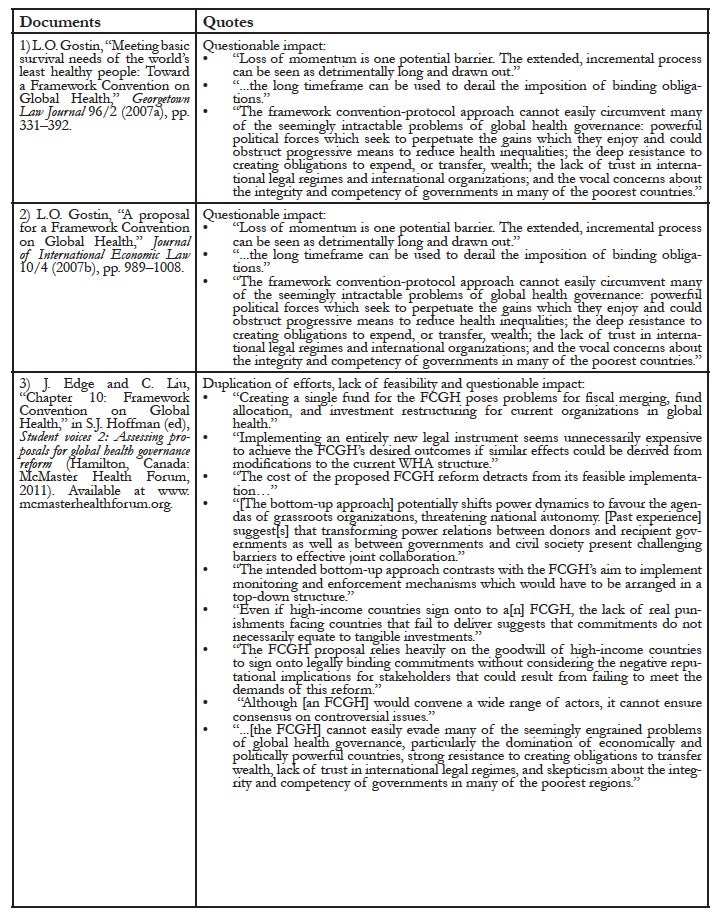

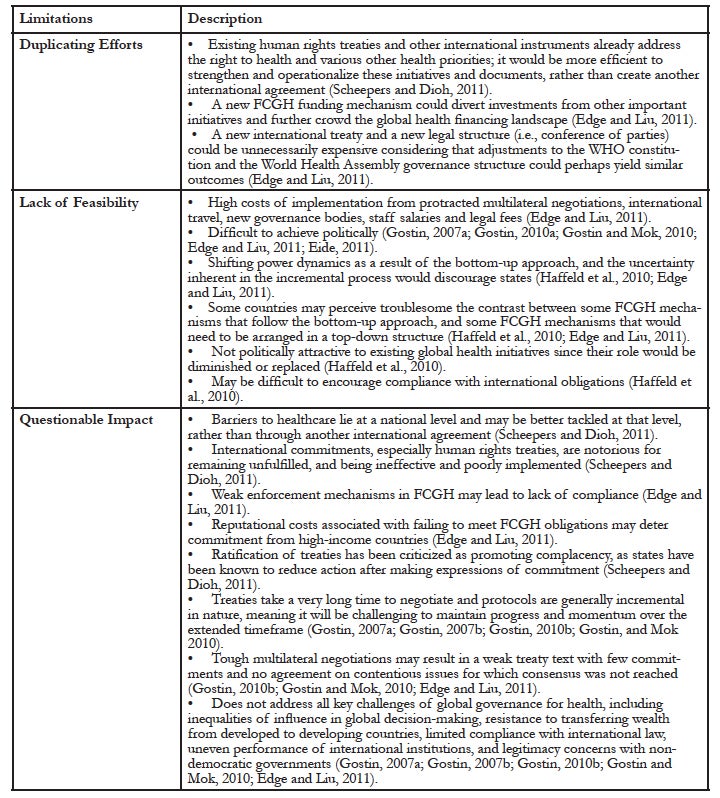

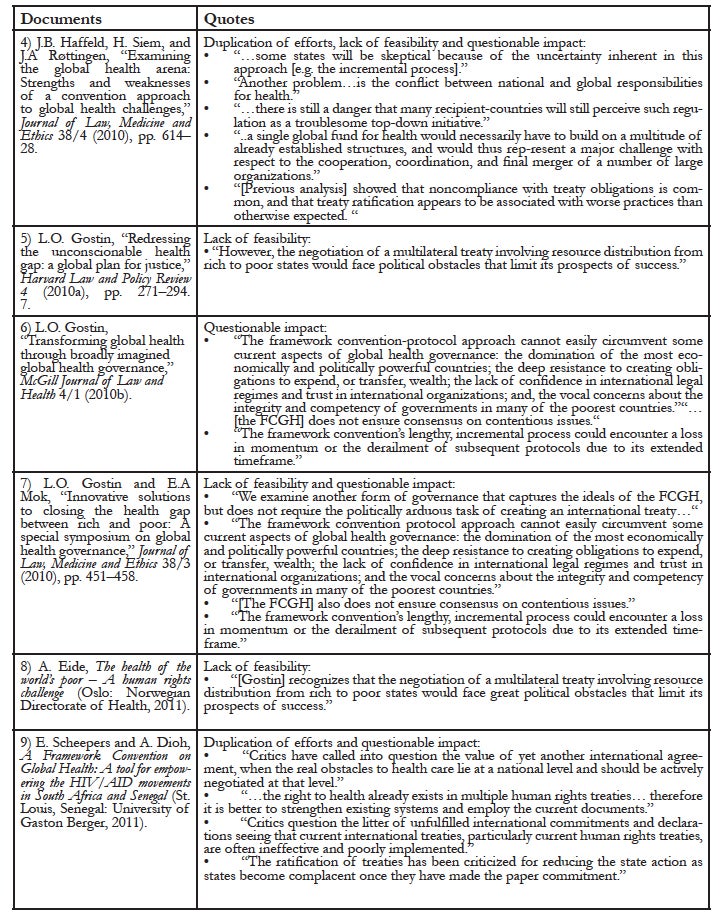

The nine documents identified various limitations of the FCGH proposal (see Appendix 1). The limitations can be grouped into three categories (see Appendix 2).

The first identified limitation was the possibility for duplicating effort. Various human rights treaties, international institutions, and global funds were said to already address the concerns that would be addressed by the proposed FCGH.15 Forming new legal frameworks, new structures, and new obligations could interfere with or even undermine existing initiatives. One study highlighted how the proposed FCGH would create a conference of parties that would function similarly to the World Health Assembly—the plenary governing body of WHO—and could over time compete with it or even supplant it.16

The second identified limitation was about a possible lack of feasibility. The FCGH proposal was said to be expensive both in terms of negotiating an agreement and implementing it thereafter.17 It was also argued that political agreement would be difficult to achieve. States may be discouraged by the idea of taking on increasingly onerous legal commitments demanded by the framework convention text and later protocols, as well as the inherent uncertainty of the incremental convention-protocol process.18 Securing agreement on legally binding financial commitments may be particularly challenging. Also, it was said that other than academics, there were few natural champions or partners who would be inclined to advocate for this approach over competing alternatives.19 Indeed, today’s most powerful actors and institutions, including the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and WHO, may perceive the proposed FCGH as a threat to their strategic interests and may obstruct it.20 The UNAIDS Secretariat’s recent endorsement of the FCGH proposal does, however, demonstrate support among some key constituencies.21

The third identified limitation was about the FCGH’s questionable impact. Concerns included the length of time needed for it to become effective and the hitherto-unproven impact of international law on population health outcomes.22 The FCGH proposal was also said to not address several fundamental challenges in global governance for health, such as the democratic deficit in global decision-making,23 political accountability,24 cross-sectoral interdependence,25 institutional fragmentation,26 and regime complexity.27 It was argued that barriers to realizing the right to health lie primarily at the national level, such that new international laws, which are notorious for being ignored and remaining unfulfilled, would lack sufficient carrots or sticks to achieve impact commensurate with its costs.28 High-income countries, especially the United States, were identified as likely candidates for declining to participate in FCGH negotiations, refusing to ratify the final agreement, or failing to implement the resulting international legal obligations domestically.29 Some of the biggest global governance challenges for health were also said to be left unresolved by the FCGH proposal.30 As the proposal’s progenitor noted, unresolved challenges include: “the domination of the most economically and politically powerful countries; the deep resistance to creating obligations to expend, or transfer, wealth; the lack of confidence in international legal regimes and trust in international organizations; and the vocal concerns about the integrity and competency of governments in many of the poorest countries.”31

Critical analysis

These three limitations identified through the systematic review serve as a helpful starting point for a list of concerns that should be addressed to increase the benefits and attractiveness of the FCGH proposal. But there are at least a few others as well. For example, there is the well-known challenge of including financial commitments in legally binding multilateral instruments. No such mechanism exists for global health. Recent negotiations were not successful in establishing one for research needs related to diseases that predominantly exist in low-income countries despite overwhelming need, expert support, and civil society advocacy.32 Besides membership fees to international institutions, the only major financial commitments rooted in international law seem to be for the Multilateral Fund for the Implementation of the Montreal Protocol and the to-be-implemented Green Climate Fund.33

In addition to the limitations identified (and those that remain to be recognized), potential unintended negative consequences of the proposal must also be uncovered and assessed to minimize risks of harm. Opportunities for mitigating these consequences need development and exploration.

Negative consequences can derive from the FCGH’s proposed form, which, as it has been proposed, involves the use of WHO’s constitutional authority to facilitate the negotiation of a new international health law. Consequences can also stem from the FCGH’s proposed functions, which include influencing national health and foreign aid budgets, realizing health rights, and resetting global governance for health.

Potential unintended negative consequences of the FCGH’s proposed form

The proposal for an FCGH is not the only call for new international health laws. Legal enthusiasts have put forward proposals for treaties addressing a range of issues, including alcohol, biomedical research, chronic diseases, counterfeit drugs, obesity, impact evaluations, and nutrition.34

But international law is not the perfect solution to every challenge. All laws carry significant costs and consequences. For example, an FCGH would need to be drafted, ratified, and enforced, which would involve expensive international travel, big meetings, and armies of staff. New and possibly duplicative governance structures would be costly to set up and maintain. Many potential opportunities, outcomes, and initiatives would have to be forgone after allocating the funds and attention required to achieve agreement on an FCGH; these limited resources could perhaps be better spent on other initiatives if they were to achieve greater results in more cost-effective ways. Indeed, the point at which states would agree to an international law like the proposed FCGH is also exactly when it is probably no longer needed.

One of the greatest advantages of international law is how it provides a compelling language with which to argue for placing certain priorities above the usual political process and to exclude them from messy politicking. However, this prioritization is also a threat. The reality of limited resources means that every government decision is essentially an expression of its ethics, priorities, and values. The costs of international law make it no different. Since all international laws have costs, which must be accounted for and financed, their articles and provisions must be treated as competing claims on limited public resources rather than undeniable demands, obligations, or privileges. Instead of deferring to foreign judgment, reliance on public resources means that citizens and their political representatives should be entitled to decide which international laws will be prioritized for implementation. Claiming that all international laws are beyond usual priority-setting processes and tradeoffs is not only unrealistic but hardly ever justifiable. Basic human rights and jus cogens norms may be among the only exceptions, the latter of which are peremptory norms so important that international law forbids their violation by all states no matter whether or not states actually agreed to adhere to them. Examples of jus cogens norms include genocide, slavery, torture, and wars of aggression. Any new norms or requirements contained in an FCGH are unlikely to rise to this level.

Adopting an FCGH as a way to address global health challenges may also bring into global health the whole set of principles, rules, norms, and procedures that are part of legal regimes. This is perhaps its greatest strength, but it can also be a great weakness. Legal systems are not perfect; the international legal system is particularly challenged. Access to justice is often elusive, especially for poor states and those without large teams of legal representatives. Lawyers and judges—rather than researchers, health professionals, and elected officials—reign supreme. Emphasis in legal systems is on ensuring good process rather than good results, because so often there is little clarity on what constitutes the correct outcome. Legalization means that evidence-informed decision-making, results-based approaches, and goal-oriented strategies may fall by the wayside, especially as ministries of foreign affairs take the lead in negotiations and prioritize different concerns than their health ministry colleagues. International law also technically shuts out civil society organizations and private sector companies because they lack international legal personality and have no formal role in adopting or ratifying treaties, even if they are widely seen as vital contributors, not to mention the impact of their advocacy on government positions. Legal instruments have a track record of having lots of aspirational statements but few specific or enforceable commitments.35

Legalizing political interactions also carries the risk of coercively cementing paternalistic relationships between powerful states and those less powerful states which must follow them. While international law-making is technically “democratic” among sovereign states, the process is often dominated by the disproportionate influence of more powerful participating states who often set the terms of international laws based on standards they already meet and requirements that promote their own strategic interests. The equalizing role of international civil society organizations is not without risks as well. For advocacy and litigation, encouraging adherence to international standards by foreign NGOs—which are themselves so often funded, controlled, and operated by the world’s most privileged people—may be seen by the same underrepresented people these NGOs purport to serve as unhelpful interference in their country’s own decision-making and priority-setting processes.36

Potential unintended negative consequences of the FCGH’s proposed functions

While an FCGH would serve many functions, three reforms seem particularly fundamental to the proposal: influencing national health and aid budgets, realizing the human right to health, and resetting global governance for health. All three may potentially lead to unintended negative consequences.

First, influencing national health budgets from afar is akin to the previously mentioned concerns about interfering and imposing values on less powerful countries, even if not achieved through coercive legal mechanisms. Given resource limitations and the reliance of many countries on patron-client relationships, global directives could force poorer states to prioritize the ‘global consensus’ over their own local initiatives,37 even if the latter will be more contextually appropriate, less expensive, and yield better health outcomes than global edicts. Promised financial support from wealthy countries is often not delivered, and poor countries usually cannot withdraw from international treaties without financial, security, or reputational consequences.

Similarly, influencing the foreign aid budgets of wealthier countries is also not without risks. Any binding commitment on countries could unwittingly fix their financial contributions to global health at too low a level, or could displace or delay important investments in other sectors, including those sectors that are fundamental to the economic, environmental, and social determinants of health such as education, food, and housing.

Second, the FCGH proposal’s focus on defining and realizing the right to health could petrify in perpetuity a certain idea of what is needed to address rapidly changing global health challenges and freeze the basic package of health care services included as part of this human right. This contrasts with the ability to use current flexibility to promote incrementally progressive interpretations over time. Given the individual nature of human rights and courts as the human rights enforcement apparatus, this focus may also unintentionally prioritize individual rights over population-wide well-being. In an era where there is increasing recognition of the importance and cost-effectiveness of public health interventions, a focus on individuals and individual health care services may be moving in the wrong direction.

Third, any attempt to reset and improve global governance for health could also result in harmful consequences. The FCGH proposal specifically presents the risk of deepening disjunctures within global governance for health, weakening existing global architecture, encouraging additional institutional fragmentation, reducing participation opportunities for non-state actors, and offering sub-optimal solutions for each global governance challenge. It could in many ways duplicate the role and functions of WHO’s governing bodies and secretariat, which would almost surely result in devastating consequences for the agency if not managed properly.

This prospect of further exacerbating regime complexity is not necessarily a vice. Indeed, the presence of nested, parallel, and/or overlapping non-hierarchical regimes38 can offer multiple avenues for moving agendas forward, contribute to issue resilience, create a market of forums for forum shoppers, and facilitate ‘horse trading’ between regimes that can allow progress in the face of negotiating logjams and political deadlock. In other words, it can foster increased competition and, in turn, institutional innovation. For example, when an agreement on international patent law reached an impasse at the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the issue was moved to the World Trade Organization (WTO) where an Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) was eventually reached in 1994. This forum-shift—which significantly affected access to medicines and incentives for research and development of health products—occurred despite incompatibility between the positive obligations TRIPS imposes on states and the traditional role of the international trade system in promoting negative obligations, such as disallowing tariffs and discrimination against foreign entities.39

But regime complexity can have negative consequences too. In addition to the usual inefficiencies of duplication and fragmentation, regime complexity can make it more difficult to locate political authority, identify who is making which policies, and figure out how to hold deciders accountable for their decisions. It can also undermine global governance more broadly by diluting the power of existing institutions, weaken international legal obligations by increasing contradictory mandates, and diminish compliance with them by raising administrative burdens and transaction costs.40 These consequences are potentially devastating: in many respects, the inefficiencies and democratic deficits they deepen represent the greatest preoccupations of the field of global governance for health.41 But perhaps even more worrisome is how these consequences are particularly harmful for weaker states and civil society, given these actors’ comparatively fewer resources and lower capacity to create new institutions and navigate complicated regime complexes.42

Specifically, from a global health perspective, the FCGH proposal’s comprehensive scope means it adds to regime complexity by essentially presenting a work-around solution for mitigating and compensating for the failures of WHO to achieve on the bold promise of its visionary constitution. This is in contrast to the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) and proposals for new international health laws that have generally held a very narrow focus. Like regime complexity’s effects on global governance broadly, replicating facets of WHO’s mandate is not necessarily a bad thing. Indeed, in a development context, the University of Toronto’s Mariana Prado has found ‘institutional bypass’ to be a very successful strategy when reforming dysfunctional national institutions seems too difficult or has proven impossible.43 Prado described this strategy as a type of “coronary bypass for governments,” which “creates new pathways around clogged or blocked institutions.”44 In this case, WHO is clearly the clogged or blocked institution that has been widely criticized and that is the focus of the FCGH’s bypass structure. Over the years WHO has been called “bureaucratic,”45 “complex,”46 and “outdated.”47 Even its own secretariat, including its current director-general, Margaret Chan, have argued that the agency lacks the resources, authority, independence, or impartiality necessary to fulfill its vast responsibilities.48

The problem with the FCGH’s proposed institutional bypass, however, is that it only represents a partial bypass. The proposal as currently articulated calls for creating a new governance structure that is completely and totally reliant on WHO’s existing institutional framework. This means the FCGH is likely to suffer from many of WHO’s disadvantages without benefiting from the clean slate typically afforded to new institutions. The FCGH will be in competition with WHO, but will not be free from its constraints or influence. Competition in the global market can be good, but in this case the world is likely to only get the bad dimensions of partly internal competition—like duplication, inefficiency and destructive practices—since the new FCGH structure would not be able to totally subvert or undermine the old WHO structure on which it existentially depends. This possibility of encouraging counterproductive competitive practices is evidenced by informal reports of how the FCTC has caused such practices between the WHO-hosted FCTC Secretariat and WHO’s tobacco control unit. The wide-ranging nature of the FCGH proposal means that counterproductive competition could be even more extensive and damaging to WHO than existing treaties.

Mitigating potential dark sides of the FCGH’s virtues

The limitations and potential unintended negative consequences identified in this systematic review and critical analysis point to several opportunities for revising the current FCGH proposal to address its weaknesses and strengthen its potential for impact.

Option #1: Abandon international law and pursue less contested commitment mechanisms

The key objective of an FCGH is centered on the human right to health and the responsibilities of states in realizing this right for the least healthy people, both domestically and internationally. This is an admirable and important goal. But rather than expending resources on reaffirming this right that was already legalized in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (among others), and forging its associated norms into new stone, it may be more useful to interpret and operationalize existing legal commitments and secure better arrangements for accountability and transparency in how the fulfillment of this right is pursued.

Accordingly, efforts in this area may be more impactful and cost-effective if focused on creating platforms for articulating the right to health, learning from country experiences, and promoting fairer and greater funding for assisting countries in delivering on their right to health responsibilities. But these functions do not require new international law, nor do they require new hegemonic structures. Existing mechanisms for pursuing these functions are numerous, and there are a plethora of cheaper non-legal approaches for filling any gaps in global governance architecture should advocates and countries perceive that need.

Instead of choosing a commitment device like international law that formally limits the actors involved to states and some regional entities, it may be more strategic in the long term to pursue arrangements that also formally engage civil society organizations and private sector companies as appropriate. A multi-stakeholder approach that builds on each stakeholder’s strength will likely improve inputs, foster better deliberations, increase buy-in among the range of human rights actors, and achieve better implementation from all constituencies. The use of international law as a commitment device should be reconsidered in this context of wanting to involve non-state actors. Other commitment mechanisms are likely capable of achieving the objectives and functions desired by FCGH advocates and could likely achieve a new “Framework for Global Health” without all the limitations and potential negative effects of law.

For example, in pursuing mutually shared goals, states can commit themselves to each other through contracts, political declarations, or institutional reforms, in addition to international law. Contracts, which are also legal instruments, involve fewer formalities and are used every day by governments to transfer money, exchange goods, buy equipment and procure services. They are binding under domestic law and enforced in domestic courts. Political declarations, while not legally binding, are still powerful public expressions of commitment and intention. They are often called “guidelines,” “resolutions,” “statements,” or “codes of practice,” and they can be issued unilaterally at any time or adopted multilaterally through entities such as the General Assembly of the United Nations (UN). Successfully embedding FCGH content into the post-2015 development framework, for example, could be more influential and impactful than any kind of legal instrument. Institutional reforms can also be used as a mechanism to commit states to each other. This often entails having to fund new activities or meet new standards that are adopted by international organizations in which states have membership.49

Legal commitment mechanisms do have their advantages. International law and contracts are very clear expressions of intent and become part of established international or domestic legal systems. But this clarity is costly. As argued above, it can take longer to negotiate highly formal legal instruments than political declarations, the former of which are often determinedly watered down during consensus-building negotiations. States may also feel that legal instruments limit the future exercise of their sovereign rights, often making them less desirable for the most powerful states and diminishing political feasibility.50

Perhaps more concerning is how the periscopic focus on any particular commitment device, like international law, can distract advocates from other implementation mechanisms that are potentially more important. Indeed, when states make agreements, they face many choices about how the content of their agreement should actually be implemented from fiscal, operations, and accountability perspectives. Certainly states must decide 1) how they will commit to one another, but they also need to decide how to 2) raise funds, 3) manage finances, 4) allocate funding, 5) set priorities, 6) make subsequent decisions, 7) administer activities, 8) resolve disputes, 9) appeal decisions, 10) promote compliance, 11) enhance transparency, and 12) monitor each other’s performance. Choices are diverse, each with its own consequences. For example:

- Finances can be managed through specialized multilateral funds, financial institutions, membership organizations, or coordinated self-management;

- Decisions can be made through unanimity, consensus, equal voting, modified voting, or delegation;

Activities can be administered through international organizations, sub-agencies, joint ventures, or self-organizing processes; - Compliance can be promoted through legal processes, institutional consequences, economic sanctions, or political pressure; and

- Oversight can be provided by peer review, expert review, self-reports, or civil society.51

Good alternatives exist for implementing any sort of international agreement for which a package of appropriate implementation mechanisms can be devised. The full range of options and any possible mixes or packages must be considered and compared to their competing alternatives in order to achieve the optimal result. The particular arrangement represented by the FCGH proposal is only one option. From an impact perspective, the best outcome could perhaps involve new international law, but more likely it will involve other less contested commitment mechanisms combined with more powerful accountability mechanisms for better compliance, transparency, and oversight. The existing Millennium Development Goals framework is one example where accountability mechanisms have been more important than the particular form in which states happened to express their commitment (i.e., Millennium Declaration). The post-2015 development framework will likely pursue this same model, and may turn out to be equally powerful.

Option #2: Raise the ambitions of current WHO reform efforts and seek changes to its constitution

If international law is deemed essential, FCGH advocates should then reconsider whether adopting a new international law would be more effective than simply revising an existing one. The most obvious option is to revise WHO’s constitution, which, like any international law, could be used to fill gaps in global governance, hopefully in ways far more revolutionary than the meek evolutionary changes to the agency’s governance, management, programming and priority setting currently being discussed as part of “WHO reform” efforts.52 In effect since 1948, WHO’s constitution has near-universal ratification, with 194 state parties, and grants extraordinary legislative powers uncommon in today’s less internationalist environment. Yet from its inception, WHO’s constitution and institutional design have never allowed the organization to deliver on its mandate. Regional offices work separately from global headquarters, directors-general are elected in secret, and the executive board has become a place for politicians to plan the next World Health Assembly, rather than a technical body of health experts as was originally intended.53 WHO staff members have not always prioritized systematic reviews of research evidence over expert opinion as they should,54 nor have the organization’s recommendations always aligned with the best available research evidence.55 WHO has failed to engage non-state actors in a meaningful way that would capitalize on the ideas, creative energy, and resources they can bring to the table.

Reforming WHO’s constitution could achieve the goals of an FCGH by enabling the UN agency to work productively in bringing coherence to global governance for health, promoting health rights, and raising new funds for their fulfillment. In this context, FCGH advocates would not need to demand new law, but rather could simply challenge the level of ambition (or the lack thereof) in the current WHO reform process to include revision of its governing instrument. States, for example, could be encouraged to split WHO into two entities with separate responsibilities. The first entity could be a global political platform that brings states together for negotiating international cooperation on health issues, just like the proposed FCGH conference of parties. Freed from these political functions, the second entity could strive to be a truly world-leading global public health agency with the top-notch technical capacity needed to properly set evidence-based standards, support research, and lead programmatic activities in a similar way and with the same independence that the U.S. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention and the European Centre for Disease Prevention & Control, for example, operate vis-à-vis their respective governing institutions.

Option #3: Mobilize for a separate political platform that completely bypasses WHO

The advantage in seeking more ambitious WHO reform over the adoption of new international law is how the former is already partially under way and how it would avoid the parasitic potential of a new dependent sub-regime. Indeed, when considering the literature on institutional bypass, it becomes clear that FCGH advocates should either seek fundamental WHO reform or they should completely circumvent that UN agency. The current middle path and pursuit of these two goals simultaneously is probably impractical. If it is believed that WHO’s constitution can be revised and modernized, it probably makes sense to pursue that route. If, however, this belief is contested, which is reasonable given the seeming lack of ambition and leadership on the degree and depth of reform, there may be arguments to pursue a real institutional bypass arrangement that fully circumvents WHO and avoids its influence and reach.

The possibility of having cake (i.e., an FCGH) and eating it too (i.e., strengthening WHO) remains unsubstantiated. It is far more likely that these two goals are mutually incompatible. There are only two ways in which any proposal could make WHO more effective: strengthening its governing bodies or its secretariat. It is hard to see how creating a new governing platform with nearly identical state membership, structure, and powers as WHO’s World Health Assembly would in any way enhance the latter’s functioning. That is, unless one believes that WHO needs competition from a reasonably matched rival to induce sufficient fear of institutional death or irrelevance for member states to allow the UN agency to actually reform itself. This is a possible but unlikely perspective so long as the same member states are also the creators and rulers of the new governance platform. Forming a new FCGH secretariat, even if based within WHO, would only serve to undermine WHO’s secretariat, as it would have little influence over the new staff. And even minimal levers of influence could be bypassed with new buildings, new supports, and new systems. Regardless of whether an FCGH is negotiated pursuant to Article 19 of WHO’s constitution and branded as a “WHO” treaty, real power would be vested in a new conference of parties and secretariat that over time is likely to develop its own strategic interests and resist WHO’s control or influence.

Some may question whether a proposal for new global health law could ever fully circumvent WHO. The UN agency will naturally loom large in any debate on global health law, particularly multilateral negotiations among state parties. The two health treaties adopted under its auspices (i.e., FCTC and International Health Regulations) will also undoubtedly be on everyone’s minds as a template or point of comparison irrespective of whether or not they are explicitly mentioned. But even if an FCGH could not fully escape WHO’s long shadow, implementing the proposal outside WHO’s formal structures at least avoids many of the aforementioned problems that are predicted for partial institutional bypasses.

Potential alternative hosts for an FCGH include other UN bodies like the Security Council, Human Rights Council, and Economic and Social Council, as well as other existing and new entities that could perhaps have more innovative and inclusive governance arrangements than purely state-based institutions that follow the principle of sovereign equality. Working outside of WHO also means that treaties need not be negotiated with the participation of all its 194 member states. While universal participation is often assumed to be better, the enhanced representativeness and perceived legitimacy it offers comes with trade-offs and significant costs. Restricted participation in negotiating international legal agreements has two advantages: better compliance and more precise content. Better compliance is achieved by having stronger compliance mechanisms, which are more likely to be implemented by fewer states who all plan to follow their new obligations, and consequently have a vested interest in enforcing agreements against any state that violates its obligations. More precise content is possible by restricting participation to states that at the outset share interests to a greater extent and hold a common vision for the agreement. Under this approach, other states can join later and may be encouraged by the greater rents generally accrued to participants of more precise and enforceable agreements.56 Starting small and expanding later may possibly achieve a viable agreement with almost universal participation, which may be sufficiently in line with the global health community’s values. This approach may be inappropriate and incompatible with the FCGH proposal’s principles and purposes, but nevertheless, the opportunity costs of undertaking negotiations through WHO with universal participation should be recognized and fully considered when assessing competing alternatives.

Option #4: Narrow the scope of sought changes and seek more precise commitments

Finally, if FCGH advocates find these alternatives to international law and WHO to be unappealing, they should consider narrowing the scope of their proposal to a discrete transnational and timeless issue that actually benefits from and justifies the coercive nature of international legal instruments. A convention on financing for global health, for example, could serve a function that WHO has not been able to fulfill—as evidenced by its $2 billion USD annual budget compared to global health aid’s $28.2 billion USD—and which may be needed to continue the scale of progress that has been achieved over the past two decades.57,58, An international agreement with this narrower focus would still represent an ambitious change in global governance, given how redistributing financial resources through international law has almost no precedent. Unfortunately, it also likely has little political traction, but certainly more so than a broader framework convention that includes these financing goals along with many other potentially onerous obligations.

Conclusion

The FCGH is a bold idea worthy of debate and full consideration. Its stated goals are important and its merits are many. But as this systematic review and critical analysis has shown, the proposal also has many possible limitations and unintended consequences. These dark sides must be further articulated, analyzed, and assessed along with its virtues and in comparison to competing proposals for global governance reform, especially given the importance of the decision at hand to billions of people around the world and the size and range of effects it would cause. FCGH advocates should re-examine whether both their proposal’s form and functions actually best serve their goal of meeting the basic survival needs of the world’s least healthy people. Alternative options and implementation mechanisms are available and should be considered. Specifically, proponents of an FCGH should reconsider whether new international law is actually needed to achieve their prime objectives and how directive any global framework should be. Proponents should also decide whether they wish to work within WHO’s existing processes or bypass its institutional architecture; positive outcomes seem unlikely should they pursue a compromise approach involving the combination of elements from both strategies.

Four options for revising the FCGH proposal seem particularly worthy of further consideration (see Table 1). The first option is to abandon the current call for new international law and instead pursue a less formal framework for global health. Such a framework could be broad in scope, involve a multi-stakeholder platform with active participation of both state and non-state actors, and be unconstrained by the principles, norms, rules, and procedures of international law-making. A second option is to fill gaps in global governance by changing WHO’s constitution—in ways far more extensive and fundamental than anything being discussed in this latest round of WHO reform efforts—to enable the UN agency to actually deliver on its ambitious mandate, to work efficiently as one global entity, and to be accountable for promoting the right to health and global health policies that are based on the best available research evidence. WHO’s member states could, for example, divide WHO into two separate entities, one facilitating international political cooperation and the other serving technical functions. Alternatively, if advocates believe legalization is imperative and WHO constitutional reforms are unlikely, then a third possible option is to pursue implementation of the proposal outside the confines of WHO. A new platform for negotiations between states could be constituted as a wholly new entity (as conferences of parties generally are) or could be sponsored by a different UN body. This approach could be particularly effective if it freed WHO from the burden of simultaneously being a technical agency and the world’s focal point for global health politicking, achieving a result much like the suggested constitutional reforms. A fourth option is to significantly narrow the scope of the FCGH so that it only addresses a single governance issue, such as financing for global health. A specific agreement could perhaps be more optimally crafted to enable precise international commitments and encourage voluntary participation from non-state actors, while limiting overlap with WHO, the human rights system, and other existing regimes.

Table 1: Four options for strengthening the FCGH proposal

We believe that taking stock of the FCGH’s potential limitations and unintended negative consequences will help proponents identify these challenges now so they can address them before implementation. For if states choose to pursue an FCGH, their lawyers and diplomats will naturally take over the process from advocates who may frustratingly find themselves at the sidelines of negotiations unable to mitigate any negative effects their proposal may cause as they once could have done at an earlier stage in the process. For FCGH supporters, that outcome and missed opportunity could be the greatest tragedy of all.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Charles Clift, Sophie Harman, Suerie Moon, Mariana Prado, three reviewers and the editors for feedback on earlier drafts of this paper, and to Zain Rizvi for excellent research assistance.

Appendix 1: Direct quotes from the nine documents that identified limitations of the FCGH proposal

Appendix 2: Summary of FCGH limitations identified in the systematic review

Appendix 2: Summary of FCGH limitations identified in the systematic review

Steven J. Hoffman, BHSc, MA, JD, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics and an Adjunct Faculty with the McMaster Health Forum at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. He is currently a Visiting Assistant Professor in the Department of Global Health and Population at the Harvard School of Public Health and a Visiting Scholar with the Harvard Global Health Institute, Harvard University.

John-Arne Røttingen, MD, PhD, MSc, MPA, is a Professor in the Department of Health Management and Health Economics at the Institute of Health and Society at the University of Oslo, Norway. He is currently a Visiting Professor in the Department of Global Health and Population at the Harvard School of Public Health and a Visiting Scholar with the Harvard Global Health Institute, Harvard University.

Please address correspondence to the authors c/o Steven J. Hoffman, hoffmans@mcmaster.ca.

References

1. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Financing global health 2012: The end of the golden age? (Seattle, WA: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2012). Available at http://www.healthmetricsandevaluation.org/publications/policy-report/financing-global-health-2012-end-golden-age.

2. UNICEF, Committing to child survival: A promise renewed (New York: UNICEF, 2012). Available at http://www.unicef.org/videoaudio/PDFs/APR_Progress_Report_2012_final.pdf; United Nations Development Program, The Millennium Development Goals report (New York: United Nations, 2012). Available at http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/MDG/english/The_MDG_Report_2012.pdf.

3. L.O. Gostin and E.A. Mok, “Grand challenges in global health governance,” British Medical Bulletin 90/1 (2009), pp. 7-18.

4. S.J. Hoffman (ed), Student voices 2: Assessing proposals for global health governance reform (Hamilton, Canada: McMaster Health Forum, 2011.) Available at http://www.mcmasterhealthforum.org/images/docs/student-voices-2-assessing-proposals-for-global-health-governance-reform.pdf.

5. L.O. Gostin, “Redressing the unconscionable health gap: A global plan for justice,” Harvard Law and Policy Review 4 (2010a), pp. 271-294; G. Silberschmidt, D. Matheson, and I. Kickbusch, “Creating a Committee C of the World Health Assembly,” The Lancet 371/9623 (2008), pp. 1483-1486; I. Kickbusch, W. Hein, and G. Silberschmidt, “Addressing global health governance challenges through a new mechanism: The proposal for a Committee C of the World Health Assembly,” Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics 38/3 (2010), pp. 550-563.

6. D.P. Fidler and L.O. Gostin, Biosecurity in the global age: Biological weapons, public health, and the rule of law (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008); G. Cometto, G. Ooms, A. Starrs, and P. Zeitz, “A global fund for the health MDGs?” The Lancet 373/9674 (2009), pp. 1500-1502.

7. T.K. Mackay and B.A. Liang, “A United Nations Global Health Panel for global health governance,” Social Science and Medicine 76/1 (2013), pp. 12-15; A. Banerjee, A. Hollis, and T. Pogge, “The Health Impact Fund: Incentives for improving access to medicines,” The Lancet 375/9709 (2010), pp. 166-169.

8. L.O. Gostin, “A proposal for a Framework Convention on Global Health,” Journal of International Economic Law 10/4 (2007b), pp. 989-1008.

9. K.J. Alter and, S. Meunier, “The politics of international regime complexity,” Perspectives on Politics 7/1 (2009), pp. 13-24; D.W. Drezner, “The power and peril of international regime complexity,” Perspectives on Politics 7/1 (2009), pp. 65-70.

10. L.O. Gostin, E.A. Friedman, G. Ooms, et al., “The Joint Action and Learning Initiative: Towards a global agreement on national and global responsibilities for health,” PLoS Medicine 8/5 (2011), p. e1001031.

11. D. Kennedy, The dark sides of virtue: Reassessing international humanitarianism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004).

12. J. Thomas and A. Harden, “Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews,” BMC Medical Research Methodology 8/45 (2008); E. Barnett-Page and J. Thomas, “Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review,” BMC Medical Research Methodology 9/59 (2009).

13. E. Scheepers and A. Dioh, A Framework Convention on Global Health: A tool for empowering the HIV/AID movements in South Africa and Senegal (St. Louis, Senegal: University of Gaston Berger, 2011); J. Edge and C. Liu, “Chapter 10: Framework Convention on Global Health,” in S.J. Hoffman (ed), Student voices 2: Assessing proposals for global health governance reform (Hamilton, Canada: McMaster Health Forum, 2011). Available at http://www.mcmasterhealthforum.org/images/docs/student-voices-2-assessing-proposals-for-global-health-governance-reform.pdf; J.B. Haffeld, H. Siem, and J.A. Røttingen, “Examining the global health arena: Strengths and weaknesses of a convention approach to global health challenges,” Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 38/4 (2010), pp. 614–28; A. Eide, The health of the world’s poor – a human rights challenge (Oslo: Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2011); L.O. Gostin and E.A. Mok, “Innovative solutions to closing the health gap between rich and poor: A special symposium on global health governance,” Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 38/3 (2010), pp. 451–458; L.O. Gostin, “Redressing the unconscionable health gap: A global plan for justice,” Harvard Law and Policy Review 4 (2010a), pp. 271-294; L.O. Gostin, “Meeting basic survival needs of the world’s least healthy people: Toward a Framework Convention on Global Health,” Georgetown Law Journal 96/2 (2007a), pp. 331–392; L.O. Gostin, “Transforming global health through broadly imagined global health governance,” McGill Journal of Law and Health 4/1 (2010b), pp. 3-16; L.O. Gostin, “A proposal for a Framework Convention on Global Health,” Journal of International Economic Law 10/4 (2007b), pp. 989-1008; S. Burris and E.D Anderson, “A Framework Convention on Global Health: Social justice lite, or a light on social justice?” Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 38/3 (2010), pp. 580–93; E. Friedman and L.O. Gostin, “Pillars for progress on the right to health: Harnessing the potential of human rights through a Framework Convention on Global Health,” Health and Human Rights: An International Journal 14/1 (2012), pp. 4-19; L.O. Gostin, “Meeting the survival needs of the world’s least healthy people: A proposed model for global health governance,” Journal of the American Medical Association 298/2 (2007c), pp. 225–228; L.O. Gostin, “Meeting basic survival needs of the world’s least healthy people: Toward a Framework Convention on Global Health,” (presentation at Georgetown University, Washington, DC, 2007d); L.O. Gostin,“Global health law governance,” Emory International Law Review 22 (2008), pp. 35-48; L.O. Gostin and L. Taylor, “Global health law: A definition and grand challenges,” Public Health Ethics 1/1 (2008), pp. 53–63; L.O. Gostin and E.A. Mok, “Grand challenges in global health governance,” British Medical Bulletin 90/1 (2009), pp. 7-18; L.O. Gostin, “The unconscionable health gap: A global plan for justice,” The Lancet 375/9725 (2010c, pp. 1504–1505; L.O. Gostin, E.A. Friedman, T. Gebauer, et al., “A framework convention on obesity control?” The Lancet 378/9809 (2011), pp. 2068–2069; L.O. Gostin, E.A. Friedman, G. Ooms, et al., “The Joint Action and Learning Initiative: Towards a global agreement on national and global responsibilities for health,” PLoS Medicine 8/5 (2011), p. e1001031; L.O. Gostin, E.A. Mok, and E.A. Friedman, “Towards a radical transformation in global governance for health,” Michael Quarterly 8 (2011), pp. 228–239; L.O. Gostin, “A framework convention on global health: Health for all, justice for all,” Journal of the American Medical Association 307/19 (2012), pp. 2087–92; L.O. Gostin and E.A. Friedman, “Towards a Framework Convention on Global Health: A transformative agenda for global health justice,” Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law and Ethics 13/1 (2013), pp. 1-75.

14. E. Scheepers and A. Dioh, A Framework Convention on Global Health: A tool for empowering the HIV/AID movements in South Africa and Senegal (St. Louis, Senegal: University of Gaston Berger, 2011); J. Edge and C. Liu, “Chapter 10: Framework Convention on Global Health,” in S.J. Hoffman (ed), Student voices 2: Assessing proposals for global health governance reform (Hamilton, Canada: McMaster Health Forum, 2011). Available at http://www.mcmasterhealthforum.org/images/docs/student-voices-2-assessing-proposals-for-global-health-governance-reform.pdf; J.B. Haffeld, H. Siem, and J.A. Røttingen, “Examining the global health arena: Strengths and weaknesses of a convention approach to global health challenges,” Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 38/4 (2010), pp. 614–28; A. Eide, The health of the world’s poor – a human rights challenge (Oslo: Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2011); L.O. Gostin and E.A. Mok, “Innovative solutions to closing the health gap between rich and poor: A special symposium on global health governance,” Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 38/3 (2010), pp. 451–458; L.O. Gostin, “Redressing the unconscionable health gap: A global plan for justice,” Harvard Law and Policy Review 4 (2010a), pp. 271-294; L.O. Gostin, “Meeting basic survival needs of the world’s least healthy people: Toward a Framework Convention on Global Health,” Georgetown Law Journal 96/2 (2007a), pp. 331–392; L.O. Gostin, “Transforming global health through broadly imagined global health governance,” McGill Journal of Law and Health 4/1 (2010b), pp. 3-16; L.O. Gostin, “A proposal for a Framework Convention on Global Health,” Journal of International Economic Law 10/4 (2007b), pp. 989-1008.

15. J. Edge and C. Liu, “Chapter 10: Framework Convention on Global Health,” in S.J. Hoffman (ed), Student voices 2: Assessing proposals for global health governance reform (Hamilton, Canada: McMaster Health Forum, 2011). Available at http://www.mcmasterhealthforum.org/images/docs/student-voices-2-assessing-proposals-for-global-health-governance-reform.pdf.

16. Ibid.

17. A. Eide, The health of the world’s poor – a human rights challenge (Oslo: Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2011); L.O. Gostin and E.A. Mok, “Innovative solutions to closing the health gap between rich and poor: A special symposium on global health governance,” Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 38/3 (2010), pp. 451–458; L.O. Gostin, “Redressing the unconscionable health gap: A global plan for justice,” Harvard Law and Policy Review 4 (2010a), pp. 271-294; L.O. Gostin, “Meeting basic survival needs of the world’s least healthy people: Toward a Framework Convention on Global Health,” Georgetown Law Journal 96/2 (2007a), pp. 331–392.

18. J. Edge and C. Liu, “Chapter 10: Framework Convention on Global Health,” in S.J. Hoffman (ed), Student voices 2: Assessing proposals for global health governance reform (Hamilton, Canada: McMaster Health Forum, 2011). Available at http://www.mcmasterhealthforum.org/images/docs/student-voices-2-assessing-proposals-for-global-health-governance-reform.pdf; J.B. Haffeld, H. Siem, and J.A. Røttingen, “Examining the global health arena: Strengths and weaknesses of a convention approach to global health challenges,” Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 38/4 (2010), pp. 614–28.

19. L.O. Gostin, “A proposal for a Framework Convention on Global Health,” Journal of International Economic Law 10/4 (2007b), pp. 989-1008.

20. M. Sidibé and K. Buse, “A Framework Convention on Global Health: A catalyst for justice,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 90/12 (2012), p. 870.

21. A. Palmer, J. Tomkinson, C. Phung, et al., “Does ratification of human-rights treaties have effects on population health?” The Lancet 373/9679 (2009), pp. 1987-1992.

22. S.J. Hoffman, “Mitigating inequalities of influence among states in global decision-making,” Global Policy Journal 3/4 (2012), pp. 421-432.

23. I. Kickbusch, “The development of international health policies — accountability intact?” Social Science and Medicine 51/6 (2000), pp. 979-989.

24. J. Frenk and S. Moon, “Governance challenges in global health,” New England Journal of Medicine 368 (2013), pp. 936-942.

25. F. Biermann, “The fragmentation of global governance architectures: A framework for analysis,” Global Environmental Politics 9/4 (2009), pp. 14-40.

26. K.J. Alter and S. Meunier, “The politics of international regime complexity,” Perspectives on Politics 7/1 (2009), pp. 13-24.

27. E. Scheepers and A. Dioh, A Framework Convention on Global Health: A tool for empowering the HIV/AID movements in South Africa and Senegal (St. Louis, Senegal: University of Gaston Berger, 2011).

28. Ibid; J. Edge and C. Liu, “Chapter 10: Framework Convention on Global Health,” in S.J. Hoffman (ed), Student voices 2: Assessing proposals for global health governance reform (Hamilton, Canada: McMaster Health Forum, 2011). Available at http://www.mcmasterhealthforum.org/images/docs/student-voices-2-assessing-proposals-for-global-health-governance-reform.pdf.

29. J. Edge and C. Liu, “Chapter 10: Framework Convention on Global Health,” in S.J. Hoffman (ed), Student voices 2: Assessing proposals for global health governance reform (Hamilton, Canada: McMaster Health Forum, 2011). Available at http://www.mcmasterhealthforum.org/images/docs/student-voices-2-assessing-proposals-for-global-health-governance-reform.pdf; L.O. Gostin and E.A. Mok, “Innovative solutions to closing the health gap between rich and poor: A special symposium on global health governance,” Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 38/3 (2010), pp. 451–458; L.O. Gostin, “Meeting basic survival needs of the world’s least healthy people: Toward a Framework Convention on Global Health,” Georgetown Law Journal 96/2 (2007a), pp. 331–392; L.O. Gostin, “Transforming global health through broadly imagined global health governance,” McGill Journal of Law and Health 4/1 (2010b), pp. 3-16; L.O. Gostin, “A proposal for a Framework Convention on Global Health,” Journal of International Economic Law 10/4 (2007b), pp. 989-1008.

30. L.O. Gostin, “Meeting basic survival needs of the world’s least healthy people: Toward a Framework Convention on Global Health,” Georgetown Law Journal 96/2 (2007a), pp. 331–392; L.O. Gostin, “Transforming global health through broadly imagined global health governance,” McGill Journal of Law and Health 4/1 (2010b), pp. 3-16.

31. WHO Director-General, Follow-up of the Report of the Consultative Expert Working Group on Research and Development: Financing and Coordination, UN Doc. No. EB132/21 (2012). Available at http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB132/B132_21-en.pdf.

32. S.J. Hoffman and J.A. Røttingen, “Assessing implementation mechanisms for an international agreement on research and development for health products,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 90/11 (2012), pp. 854-863; L. van Kerkhoff, I.H. Ahmad, J. Pittock, and W. Steffen, “Designing the Green Climate Fund: How to spend $100 billion sensibly,” Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 53/3 (2011), pp. 18-31.

33. D. Sridhar, “Regulate alcohol for global health,” Nature 482/7385 (2012), p. 302; N. Dentico and N. Ford, “The courage to change the rules: A proposal for an essential health R&D treaty,” PLoS Medicine 2/2 (2005), e14; R.S. Magnusson, “Rethinking global health challenges: Towards a ‘global compact’ for reducing the burden of chronic disease,” Public Health 123/3 (2009), pp. 265-274; Editorial, “Fighting fake drugs: The role of WHO and pharma,” The Lancet 377/9778 (2011), p. 1626; Editorial, “Urgently needed: A framework convention for obesity control,” The Lancet 378/9793 (2011), p. 741; A.D. Oxman, A. Bjørndal, F. Becerra-Posada, et al., “A framework for mandatory impact evaluation to ensure well informed public policy decisions,” The Lancet 375/9712 (2010), pp. 427-431; S. Basu, “Should we propose a global nutrition treaty?” EpiAnalysis Blog (June 26, 2012). Available at http://epianalysis.wordpress.com/2012/06/26/nutritiontreaty.

34. D. Kennedy, “The international human rights movement: part of the problem?” Harvard Human Rights Journal 15 (2002), pp. 101-126.

35. S.J. Hoffman, “Mitigating inequalities of influence among states in global decision-making,” Global Policy Journal 3/4 (2012), pp. 421-432; S. Kamat, “NGOs and the new democracy: The false saviours of international development,” Harvard International Review 25/1 (2003), pp. 65-69.

36. S.J. Hoffman and J.A. Røttingen, “Be sparing with international laws,” Nature 483 (2012), p. 275.

37. K.J. Alter and S. Meunier, “The politics of international regime complexity,” Perspectives on Politics 7/1 (2009), pp. 13-24.

38. A. Stack, International patent law: Cooperation, harmonization and an institutional analysis of WIPO and the WTO (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2011).

39. D.W. Drezner, “The power and peril of international regime complexity,” Perspectives on Politics 7/1 (2009), pp. 65-70.

40. J. Cohen, “The new world of global health,” Science 311/5758 (2006), pp. 162-167; D.P. Fidler, “Reflections on the revolution in health and foreign policy,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 85/3 (2007), pp. 161-244; L. Garrett, “The challenge of global health,” Foreign Affairs 86/1 (2007), pp. 14-38; L.O. Gostin and E.A. Mok, “Grand challenges in global health governance,” British Medical Bulletin 90/1 (2009), pp. 7-18; S.J. Hoffman, “The evolution, etiology and eventualities of the global health security regime,” Health Policy and Planning 25/6 (2010), pp. 510-522.

41. D.W. Drezner, “The power and peril of international regime complexity,” Perspectives on Politics 7/1 (2009), pp. 65-70.

42. M.M. Prado, “Institutional bypass: An alternative for development reform (2011). Available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1815442 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1815442.

43. M.M. Prado, “Like a coronary bypass, for governments,” NEXUS Winter/Fall (2010), pp. 30-31.

44. F. Godlee, “The World Health Organization: WHO in crisis,” British Medical Journal 309 (1994), pp. 1424–1428.

45. J.W. Peabody, “An organizational analysis of the World Health Organization: Narrowing the gap between promise and performance,” Social Science and Medicine 40/6 (1995), pp. 731–742.

46. A.M. Stern and H. Merkel, “International efforts to control infectious diseases, 1851 to the present,” Journal of the American Medical Association 292/12 (2004), pp. 1474–1479.

47. K. Lee, S. Collinson, G. Walt, and L. Gilson, “Who should be doing what in international health: A confusion of mandates in the United Nations?” British Medical Journal 312/7026 (1996), pp. 302–327; T.M. Brown, M. Cueto, E. Fee, “The World Health Organization and the transition from ‘international’ to ‘global’ public health,” American Journal of Public Health 96/1 (2006), pp. 62–72; P. Calain, “Exploring the international arena of global public health surveillance,” Health Policy and Planning 22/1 (2007), pp. 2-12; UK House of Lords Select Committee on Intergovernmental Organisations, Diseases Know No Frontiers: How Effective Are Intergovernmental Organisations in Controlling their Spread? (London: Authority of the House of Lords, 2008). Available at http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200708/ldselect/ldintergov/143/143.pdf; WHO, The future of financing for WHO: Report of an informal consultation convened by the Director-General (Geneva: WHO, 2010). Available at http://www.who.int/dg/who_futurefinancing2010_en.pdf; WHO Director-General, The Future of Financing for WHO, UN Doc. No. EB128/21 (2010). Available at http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB128/B128_21-en.pdf.

48. S.J. Hoffman and J.A. Røttingen, “Assessing implementation mechanisms for an international agreement on research and development for health products,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 90/11 (2012), pp. 854-863.

49. Ibid.

50. Ibid.

51. WHO Secretariat, WHO Reform, UN Doc. No. EB132/5 (2013). Available at http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB132/B132_5-en.pdf.

52. E. Minelli, “World Health Organization: The mandate of a specialized agency of the United Nations,” doctoral dissertation (2003). Available at: http://www.gfmer.ch/TMCAM/WHO_Minelli/Index.htm.

53. A.D. Oxman, J.N. Lavis, and A. Fretheim, “Use of evidence in WHO recommendations,” The Lancet 369/9576 (2007), pp. 1883-1889.

54. S.J. Hoffman, J.N. Lavis, and S. Bennett, “The use of research evidence in two international organizations’ recommendations about health systems,” Healthcare Policy 5/1 (2009), pp. 66-86.

55. E.M. Hafner-Burton, D.G. Victor, and Y. Lupu, “Political science research on international law: The state of the field,” American Journal of International Law 106/1 (2012), pp. 47-97.

56. WHO, Implementation of Programme Budget 2012-2013: Update, UN Doc. No. EB132/25 (2012). Available at http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB132/B132_25-en.pdf.

57. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Financing global health 2012: The end of the golden age? (Seattle, WA: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2012). Available at http://www.healthmetricsandevaluation.org/publications/policy-report/financing-global-health-2012-end-golden-age.