Paula Braveman

Health and Human Rights 12/2

Published December 2010

Abstract

The fields of health equity and human rights have different languages, perspectives, and tools for action, yet they share several foundational concepts. This paper explores connections between human rights and health equity, focusing particularly on the implications of current knowledge of how social conditions may influence health and health inequalities, the metric by which health equity is assessed. The role of social conditions in health is explicitly addressed by both 1) the concept that health equity requires equity in social conditions, as well as in other modifiable determinants, of health; and 2) the right to a standard of living adequate for health. The indivisibility and interdependence of all human rights — civil and political as well as economic and social — together with the right to education, implicitly but unambiguously support the need to address the social (including political) determinants of health, thus contributing to the conceptual basis for health equity. The right to the highest attainable standard of health strengthens the concept and guides the measurement of health equity by implying that the reference group for equity comparisons should be one that has optimal conditions for health. The human rights principles of non-discrimination and equality also strengthen the conceptual foundation for health equity by identifying groups among whom inequalities in health status and health determinants (including social conditions) reflect a lack of health equity; and by construing discrimination to include not only intentional bias, but also actions with unintentionally discriminatory effects. In turn, health equity can make substantial contributions to human rights 1) insofar as research on health inequalities provides increasing understanding and empiric evidence of the importance of social conditions as determinants of health; and, more concretely, 2) by indicating how to operationalize the concept of the right to health for the purposes of measurement and accountability, which have been elusive. Human rights laws and principles and health equity concepts and technical approaches can be powerful tools for mutual strengthening, not only by contributing toward building awareness and consensus around shared values, but also by guiding analysis and strengthening measurement of both human rights and health equity.

Introduction

This paper explores connections between human rights and health equity, focusing particularly on the implications for both fields of the link between social conditions and both health and health inequalities. Health equity is the concept underlying a commitment to reducing health inequalities — that is, systematic, plausibly avoidable differences in health, varying according to levels of social advantage, with worse health occurring among the disadvantaged.1 This is a timely moment to re-examine the areas of convergence and divergence between human rights and health equity, given the relatively recent accumulation of a critical mass of knowledge about the health effects of social conditions (also known as the social determinants of health). After briefly reviewing this knowledge base, the concept of health equity is examined. This is followed by a discussion of several human rights principles of particular relevance to health equity and, in many cases, to the link between social conditions and health. The final section explores the contributions that human rights and health equity can make to each other, particularly with respect to how each addresses the implications of the link between social conditions and health.

The term “human rights principles” is used throughout to refer both to those principles expressed as rights and other fundamental principles that are not generally referred to as rights in and of themselves but that, nevertheless, have major implications for the meaning of all rights. “Health” refers to health status itself and is distinguished from medical care (often called “health care,” a term not used here to avoid confusion with “health”), which, along with social conditions, is one of many important determinants of health. Several other terms used throughout this paper are defined in Table 1.

Several earlier discussions, including some by the author with Sofia Gruskin, JD, have focused on the relevance of human rights to health equity, and many authors have addressed the issue to varying extents in papers focused on other issues.2 The World Health Organization has produced materials to educate health workers about human rights and raise awareness of the potential of human rights principles to enrich efforts to improve health and promote health equity.3 The goal of this paper is to revisit the links and distinctions between rights and equity with a particular focus on the theme of this issue of Health and Human Rights — the role of social conditions in health — and in light of the recent increase in awareness and accumulation of knowledge of the latter.

Emerging awareness and understanding of how social conditions shape health and health inequalities

For many individuals, “health care” is probably the first response that would come to mind if asked to name the most important modifiable influences on health. Health-related behaviors (for example, smoking, alcohol intake, illicit drug use, physical activity, and diet) also would likely be mentioned, given the growing awareness of their health effects over the past few decades. For a long time, clean water, adequate sanitation, food safety, and protection from occupational and environmental physical hazards have been widely recognized as essential conditions for health (although often taken for granted, at least in settings where they are guaranteed). However, outside the development community or those who study or promote action on the social determinants of health, social and economic conditions in homes, neighborhoods, schools, and workplaces are generally less likely to be considered among the major influences on health.

Considerable evidence now indicates, however, that social and economic conditions — apart from access to and quality of medical care, which have undeniable importance — play a fundamental, powerful, and pervasive role in the health of populations in both resource-poor and resource-rich countries.4 The evidence includes, for example, widening social inequalities in health in the UK in the decades following the introduction of the National Health Service, which removed financial obstacles to medical care; the currently poor and progressively deteriorating US ranking on health internationally, despite higher medical care spending than any other nation; and increasing evidence and understanding of the health impact of social conditions.5 A large and rapidly growing literature documents strong and pervasive links between social and economic conditions and health in nations of all economic levels; although much remains unknown and contested, the biologic plausibility of many of those links has been documented by studies of pathways and physiologic mechanisms.6

The term “social conditions” is used here (see Table 1) — and often elsewhere — to refer to social, economic, and political conditions encompassing a wide range of modifiable factors that are outside the scope of medical care (the latter defined as preventive, curative, and rehabilitative services delivered by medical care personnel). Social conditions include potentially modifiable characteristics of both social and physical environments at the individual, household, and community levels — that is, features of homes, schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods that could be shaped by policies (at least in theory, and given sufficient political will). Social conditions also include factors at the regional, national, and global levels that often shape conditions experienced locally. Examples of social conditions include poverty, quality of housing, homelessness, educational attainment and quality, unemployment, wage levels, lack of control over the organization of work, racial residential segregation, and other forms of discrimination.

Table 1. Definitions of selected terms

Health

Physical and mental and emotional health status

Health equity

Equity means justice. Health equity is a concept based on the ethical notion of distributive justice; as argued in this paper, it also can be seen as reflecting core human rights principles. Pursuing health equity means minimizing inequalities in health and in the key determinants of health, including modifiable social and physical conditions as well as medical care. Health equity implies addressing the social as well as medical determinants of health, because they are likely to be key determinants of health inequalities.

Health inequalities or disparities

Differences in health that raise concerns about equity (justice) because they are systematically linked with social disadvantage, entailing worse health among socially disadvantaged groups. It must be plausible but not necessarily proven that these differences are modifiable. Health inequalities may reflect social disadvantage, but a causal role for social disadvantage need not be established. Health inequalities or disparities (used synonymously here) are the metric by which health equity (see above) is assessed.

Medical care

Used here to refer to what many call “health care,” to distinguish it from health (i.e., health status) itself. Medical care includes preventive services, such as vaccinations, preventive checkups and health education, as well as treatment and rehabilitation services.

The right to health

Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and several other human rights agreements include “the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.”

Social conditions

Social, economic, and political factors, including the built environment, that strongly shape, and are shaped by, those circumstances in which people live and work. Social conditions include not only features of individuals and households, such as income, wealth, educational attainment, family structure, housing, and transportation resources, but also features of communities, such as the prevalence and depth of poverty, rates of crime, accessibility of safe places to play and exercise, availability of transportation to jobs that provide a living wage, and availability of good schools and sources of nutritious food in a neighborhood.

The social determinants of health

The wide range of social (including economic and political) conditions that are strong influences on health, such as the wealth and educational attainment of the family into which one is born, neighborhood social conditions, and the social policies that determine these conditions.

For further discussion, see P. Braveman, “Health disparities and health equity: Concepts and measurement,” Annual Review of Public Health 27 (2006), pp. 167-194

Areas of recently expanded knowledge linking social conditions and health

The World Health Organization (WHO)’s Commission on the Social Determinants of Health released its final report in 2008, marking a watershed event in the history of public health and human development.7 The WHO Commission’s report was ground-breaking in its unequivocal endorsement by the health sector of the importance of addressing inequalities in social conditions in order to address inequalities in health. Backed up by massive collections of evidence and examples of promising interventions in economically, politically, and culturally diverse settings, the WHO Commission report called for action, while also acknowledging the need for further investment in research to guide future action on the social determinants of health.

Important advances in knowledge during the past 15 years include the growing understanding of biological mechanisms that may lead to cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases (for example, through pathways involving chronic stress).8 These potential mechanisms may involve multiple physiologic systems, including neuroendocrine, autonomic, immune, and inflammatory processes.9 Evidence from animal studies demonstrates that chronically high levels of stress may lead to neuroendocrine dysregulation, which, in turn, may lead to physiologic processes responsible for premature aging and chronic disease through damage to multiple organs and systems.10 Further study among humans is needed in order to draw definitive conclusions, but many experts in the field believe that pathways involving psychological responses to social conditions are likely to be among the most important explanations of the social gradient in health in affluent countries.11

Another important area of relatively recent discovery is that of early brain development. Studies reveal differences in brain development and cognitive function in response to social conditions that vary by social class.12 Studies also reveal tremendous developmental plasticity in early childhood, which offers opportunities to substantially ameliorate the adverse developmental effects of early social disadvantage through interventions such as high-quality early child care programs.13 The positive effects of early intervention also have ramifications for the future, given increasing scientific awareness of the links between social conditions experienced in early childhood and health in adulthood.14 An important pathway through which early childhood development is likely to influence health involves school readiness, which predicts school performance; the latter, in turn, predicts educational attainment, one of the most powerful predictors of economic resources (through employment opportunities), social influence and relative social standing in adulthood.15

There also has been a marked increase in studies exploring how characteristics of neighborhoods can affect the health of their residents, above and beyond the effects of characteristics of individual residents. Examples of neighborhood features that have been linked with health include the concentration of poor households in an area, levels of crime, accessibility to transportation and sources of employment, and degree of racial residential segregation. A growing body of literature suggests that the health effects of being poor in a neighborhood with concentrated poverty may differ from those of being poor in a more affluent neighborhood.16 Mechanisms explaining improved health in better-off neighborhoods may include more favorable social conditions in the wealthier neighborhoods (for example, less crime, better housing quality, safer places to play or exercise, better access to nutritious foods, and/or more social cohesion and trust), which may mitigate the disadvantages of individual residents.17 One’s perceptions of one’s social status relative to others in one’s immediate community also may have effects on health. Subjective social status and social cohesion are among the reasons that have been invoked to explain the findings observed in some studies demonstrating that members of groups residing in neighborhoods where their numbers are more concentrated paradoxically appear to have better health, despite the higher concentrations of material disadvantage in those neighborhoods.18 This example illustrates the complexity of studying neighborhood effects on health. Studying effects of communities on health is particularly challenging because characteristics of communities may influence health by shaping characteristics of households and individuals residing in them; if so, then estimating community effects while controlling for household/individual effects would entail adjusting for key mediators of the relationship between community characteristics and health; however, the existence of independent neighborhood effects is always a question of interest.

The study of links between social factors and health is in its infancy. It is challenging, in part because of the complexity of the pathways involved, with the possibility of interactions with contextual and individual factors at each step, and in part because of the often long latent period between exposure and later manifestation in measurable health outcomes. While definitive knowledge of specific pathways and mechanisms is inadequate, sufficient knowledge has accumulated to establish that in resource-rich and resource-poor countries alike, social conditions are indeed powerful influences on health.19

Conceptual frameworks for understanding the links between social conditions and health

For at least the past half century, a period during which medical technology has proliferated, prevailing ways of thinking about health often have tended to focus narrowly on medical care and/or on behaviors of individuals (for which individuals alone are held responsible). There has been little consideration of how social conditions — which could be modified by policies outside the reach of the medical care sector — might also be important to consider, including the role they can play in shaping individual behaviors. Against this background, it has been important to have conceptual frameworks to guide work on the nexus between social conditions and health; these frameworks provide important resources for thinking about both health equity and human rights, and hence for analytic work in both fields.

What influences health? And what influences the influences?

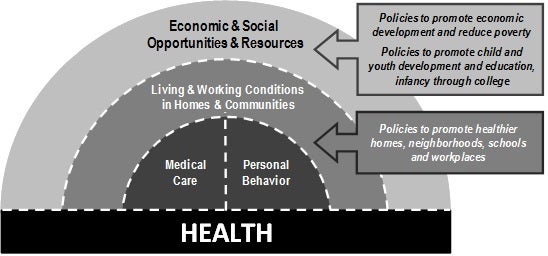

These advances in awareness of the impact of social conditions on health and health disparities led the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to establish a national commission charged with recommending promising policy directions — beyond the realm of medical care — to improve health overall and reduce health inequalities in the United States. The commission, convened during 2008–2009, was composed of nationally prominent leaders, primarily from fields outside of health care such as education, economics, labor, community development, business, and journalism.20 Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework articulated in the Foundation’s charge to the commission and rationale for the effort: that medical care and health-related behaviors are indeed important influences on health, but must be considered within the broader context of the social conditions that are more fundamental influences on health.21 While we as individuals need to behave responsibly and make healthy decisions, the societies in which we live must also act responsibly to create conditions that enable individuals to choose health. According to this framework, efforts to improve overall health and reduce health disparities in the United States must be directed beyond medical care and individual behavior change to focus more broadly on social conditions — including the economic and social opportunities and resources that shape a person’s opportunities to live, learn, work, and play in health-promoting environments. In the words of epidemiologist Geoffrey Rose, effective policies must focus at least to some extent on “the causes of the causes” rather than only on ameliorating the symptoms.22

Figure 1. What modifiable factors influence health? And what influences the influences?

Source: P. Braveman and S. Egerter, Overcoming obstacles to health: Report from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to the Commission to Build a Healthier America (Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Foundation, 2008), p. 81). Available at http://www.rwjf.org/files/research/obstaclestohealth.pdf. Copyright 2008 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation/Overcoming Obstacles to Health. Used with permission.

Understanding how health inequalities are created, exacerbated, and perpetuated

Figure 2 illustrates another useful framework for understanding and addressing the links between social conditions and health. Developed by Finn Diderichsen, now at the University of Copenhagen, and based on current knowledge of the dynamics of health and health inequalities, this framework depicts how social inequalities in health are created, exacerbated, and perpetuated through effects of social stratification. Social stratification is defined as the sorting of individuals into groups with different relative positions in social hierarchies based on characteristics including social class, race or ethnicity, gender, disability, sexual orientation or other factors associated with different levels of social, economic and political opportunities and resources, and reflecting different levels of wealth, influence, acceptance, and/or prestige.

Diderichsen’s diagram illustrates how social stratification leads to not only differential exposure to health-promoting or health-damaging experiences, but also to differential vulnerability to health damage among exposed individuals. For example, child mortality due to measles is generally confined to malnourished children who lack the immune defenses of well-nourished children and succumb to bacterial super-infections that complicate their infection with the measles virus. Similarly, exposure to adverse peer group or advertising influences may have greater effects on the health-related behaviors of adolescents from socioeconomically disadvantaged families compared with their better-off counterparts. Social stratification also results in differential consequences at the same level of sickness or injury. For example, while a highly educated professional who becomes seriously physically disabled may not lose his or her ability to earn a living, a manual laborer suffering the same disability will certainly lose his or her livelihood as a result; similarly, a person with considerable accumulated wealth and adequate medical insurance is unlikely to become homeless when faced with loss of employment due to serious illness or injury, in contrast to someone with few financial assets facing the same illness and related expenses. These differential consequences of ill health lead to further social stratification and increasing health inequalities. The pathways linking social stratification and health can be interrupted by policies, however. Rather than accepting current levels or patterns of social stratification as inevitable, this perspective calls our attention to multiple points at which interventions can be considered to ameliorate the vicious cycle of disadvantage and health inequalities over lifetimes and generations.

Figure 2. How are social inequalities in health created, exacerbated and perpetuated? (Reproduced with permission from Finn Diderichsen, University of Copenhagen)

The concept of health equity and relevance of the link between social conditions and health

The concept of health equity

Health equity is grounded in the ethical principle of distributive justice. It is the value underlying a commitment to reduce social inequalities in health; the latter are systematic, plausibly avoidable differences in health according to social advantage or disadvantage, with worse health occurring among socially disadvantaged groups.23 Social advantage and disadvantage is often reflected by measures of wealth, influence (as indicated by measures of representation in high levels of political office and executive occupations, for example), prestige, and social acceptance. Characteristics defining social advantage include: racial or ethnic group; skin color; religion, or nationality; socioeconomic resources or position (reflected by, for example, income, wealth, education, or occupation); gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or marital status; age; geography; disability; illness; political or other affiliation; or other characteristics systematically associated with discrimination or marginalization (such as exclusion from social, economic, or political opportunities).

As the terms are used in the field of health equity, “health inequalities” or “social inequalities in health” do not refer literally to all possible health differences, nor to all health differences that warrant serious policy attention. The terms refer to a specific subset of health differences that are systematically linked with social disadvantage, and that entail worse health among disadvantaged groups. In order for a health difference to be considered a health inequality, it also must be plausible, according to current scientific knowledge — but not necessarily proven — that the inequality could be reduced by societal action, given sufficient political will. Health inequalities are particularly relevant to social justice and to human rights because they may arise from intentional or unintentional discrimination or marginalization and, in any case, are likely to reinforce social disadvantage and vulnerability. The Diderichsen diagram described earlier provides a useful framework for thinking about the multiple points at which health inequalities can be created, exacerbated, and perpetuated across a lifetime and across generations.

The recent accumulation of knowledge indicating the importance of social conditions for health has strong implications for health equity. Most advocates for and scholars of health equity would argue that a commitment to health equity implies a commitment to addressing its determinants (rather than only trying to ameliorate the consequences of health inequalities). Current scientific understanding supports the notion that equity in health cannot be achieved solely by pursuing more equitable distribution of medical care, but also requires pursuing equity in the social conditions that powerfully shape health and health inequalities.

Health inequalities — The metric for assessing health equity

Social inequalities in health are the metric by which progress toward greater health equity can be measured. Measuring health inequalities requires three elements. The first is an indicator of health (such as life expectancy at birth, rates of infant mortality or chronic disease, or a positive indicator of well-being or functioning). The second is an indicator of social grouping that is associated with different levels of social advantage or disadvantage (such as different racial or ethnic groups, different income groups, and/or groups with different levels of educational attainment). Most social classifications are blunt instruments; there is a spectrum of advantage and disadvantage within each recognized group. Multiple disadvantages should be considered, along with severity and duration. And the third is a method for comparing the health indicator across the different social groups (such as a relative or absolute difference in the health indicator rates — that is, a rate ratio or rate difference — in the best- and the worst-off groups; or more complex methods, such as the slope and relative index of inequality and the concentration index, which consider the health indicator rates in all social groups, not only the extremes).24 To measure inequalities in the determinants of health, one would substitute for a health indicator a measure of factors that strongly influence health, such as food security, housing conditions, neighborhood crime levels, working conditions, or receipt of recommended medical care. A number of resources are available to guide the measurement of health inequalities for the purpose of assessing equity.25

Human rights laws and principles with particular relevance to health equity and social conditions

The human rights agreements referred to here include the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), and the officially recognized documents interpreting the ICESCR — the General Comments by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), Limburg Principles on the Implementation of the ICESCR and the Maastricht Guidelines on Violations of Economic Social and Cultural Rights.26 Together the UDHR, ICCPR, and ICESCR are referred to as the International Bill of Human Rights. The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) is also cited in this paper.27

The indivisibility of all human rights — Civil, political, economic, and social

The principle of the indivisibility, interdependence, and inter-relatedness of all human rights, as expressed in the International Bill of Rights (UDHR, ICCPR, and the ICESCR), has great relevance to both health equity and the link between social conditions and health.28 According to this principle, all human rights — civil, political, economic, social, and cultural — are interdependent and indivisible from one another. For example, according to this principle, the inability to realize one’s economic and social rights (for example, the right to a standard of living adequate for health; the right to education; and the right to the highest attainable standard of health) is recognized as an impediment to realizing one’s civil and political rights (for example, freedom of speech and assembly; and the right to participate in the political process in one’s society). Similarly, denial of civil and political rights can constitute a serious threat to health, as illustrated not only by examples of genocide and torture, but also by the health consequences of apartheid and other regimes in which particular population groups have been systematically disenfranchised. The knowledge gained over the past decade or two on the social determinants of health and health equity can contribute to human rights discussions by providing an empiric illustration supporting the principle of the indivisibility of all human rights. The indivisibility of all human rights contributes to the concept of health equity in part by underscoring, for example, that failure to realize one’s full health potential can have negative consequences for the ability to exercise one’s civil and political rights, thereby strengthening arguments regarding a societal obligation to create conditions permitting everyone to achieve her or his health potential. It also can strengthen the arguments for the need to pursue equity in all the determinants of health, including living standards, education, and the ability to participate fully in society and the political process.

The right to a standard of living adequate for health

Article 25.1 of the UDHR explicitly acknowledges the link between living conditions and health: “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family”29 The right to a standard of living adequate for health is of clear, direct, and substantial relevance to health equity, in that health equity requires an equitable distribution not only of medical care, but also of the social and economic conditions necessary for health. The right to “a standard of living adequate for health” does not entail an obligation to ensure equal standards of living, so long as a standard adequate for health is achieved. It seems reasonable that increases in living standards above a certain high level might not necessarily translate into increases in health; however, a US study including an unusually wide range of income levels showed incremental improvements in health (as reflected by functional limitations among the elderly) with income levels up to seven times the federal poverty level.30 In addition, income gradients in multiple child and adult health indicators in the US have been demonstrated in studies where the most affluent group had incomes at least four times the federal poverty level.31

The right to education

In countries of all levels of economic development, education — meaning general schooling, rather than health education — appears to be one of the most powerful social determinants of health.32 Education has appeared to be a stronger predictor of some health outcomes in some contexts than income or other measures of material resources; income or other material measures have, however, seemed more powerful predictors of other health outcomes, or in other contexts. It is difficult to disentangle education from material resources, given the importance of each in determining access to the latter. The ICESCR expresses “the right of everyone to education . . . directed to the full development of the human personality.” It notes that “education shall enable all persons to participate effectively in a free society.”33 Sen’s concept of basic capabilities has been influential in thinking about both human rights and health equity.34 In line with that concept, education, along with health, can be seen as a fundamental capability essential for fully achieving one’s health potential as well as one’s ability to function in society, including the capacity to earn a living and participate in the political process, concretely illustrating the interconnectedness of rights.

The right to the highest attainable standard of health

While the right to a standard of living adequate for health might not appear, in itself, necessarily to call for more than a minimum standard, consideration of the indivisibility of all human rights also would invoke the “right to the highest attainable standard of health.” By extension, the human rights obligation would be to ensure to all citizens a standard of living required to achieve the highest attainable standard of health.

The “right to health” — or to the “highest attainable standard of health,” as expressed in Article 12 of the ICESCR and other human rights agreements — has been criticized at times, however, for being vague or unrealistic, and therefore of limited use to guide policies.35 Despite the criticisms, there is evidence of its practical utility in the policy arena.36 Nevertheless, it is worth examining some of the shortcomings that have been articulated.

Some have pointed out that governments cannot be responsible for guaranteeing that everyone enjoys good health, let alone enjoys the highest possible levels of health.37 It is also reasonable to ask how one would monitor compliance with the right to health and how one would determine the highest attainable state of health for individuals or groups. Furthermore, without more rigorous definition, at least in theory, the right to the highest attainable standard of health could be used by some, in individual-level litigation, to justify unlimited expenditures on expensive medical technology for a few articulate, empowered individuals, to the detriment of investments in more equitable interventions with greater effectiveness in improving population health and reducing disparities. The CESCR’s General Comment No. 14 on the right to the highest attainable standard of health as expressed in the ICESCR, however, explicitly emphasizes that, “[t]he right to health is not to be understood as a right to be healthy,” because too many factors beyond a state’s control influence health. Rather, it is “the right to a system of health protection which provides equality of opportunity to enjoy the highest attainable level of health.”38

Despite the fact that the indivisibility of rights implicitly links the right to health with the right to a standard of living adequate for health, the right to health has often been interpreted as applying only to medical care, and not as frequently used to argue for the need for greater equity in social conditions. CESCR General Comment No. 14, however, makes it clear that the right to health is not limited to medical care or traditional public health domains, stating, “On the contrary, the drafting history and the express wording [of the language of the right to health] acknowledge that the right to health embraces a wide range of socioeconomic factors that promote conditions in which people can lead a healthy life, and extends to the underlying determinants of health, such as food and nutrition, housing, access to safe and potable water and adequate sanitation, safe and healthy working conditions, and a healthy environment.”39 A subsequent statement also notes, “The Committee interprets the right to health . . . as an inclusive right extending not only to timely and appropriate health care but also to the underlying determinants of health.”40 Furthermore, UDHR Article 25.1, on the right to a standard of living adequate for health (discussed above), is explicit about the connection between social conditions and health. Alicia Ely Yamin has noted that “rights must be realized inherently within the social sphere,” and that this “formulation immediately suggests that determinants of health and ill health are not purely biological or ‘natural’ but are also factors of societal relations.”41

Non-discrimination

Another human rights principle with strong and pervasive links to core concepts of health equity and relevance to the role of social conditions in health is the cross-cutting principle of non-discrimination. Non-discrimination applies to all rights; the International Bill of Human Rights and multiple General Comments specify that everyone is entitled to all human rights without distinction based on “race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.”42 In ICESCR General Comment 20, the CESCR added “ethnic origin” to this list (“‘race and colour,’ which includes an individual’s ethnic origin”), referring to all these categories as the “express grounds” for which discrimination is prohibited. 43 It is worth noting that the language explicitly includes both socioeconomic resources and social position as prohibited bases for discrimination; the terms “social origin,” “property,” and “birth” refer unambiguously and explicitly to wealth and to the relative social and economic standing of the family into which an individual is born.

General Comment 20 also addresses the “other status” category of prohibited grounds for discrimination, stating that the “nature of discrimination varies according to context and evolves over time,” therefore requiring a “flexible approach to interpreting ‘other status.’” Referring to ICESCR art. 2, para. 2, the following paragraph subheadings within General Comment 20 (as a non-exhaustive list, given the fluid nature of discrimination) identified additional “implied grounds” for which discrimination is prohibited under the “other status” category: disability (para. 28), age (para. 29), nationality (para. 30), marital and family status (para. 31), sexual orientation and gender identity (para. 32), health status (para. 33), place of residence (para. 34), and economic and social situation (para. 35).

While the ICESCR itself does not state that priority attention should be given to disadvantaged groups, the UN Committee on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights, has made it unambiguously clear, both in their General Comments on the ICESCR, and in their comments on the reports that state parties are required to submit at regular intervals, that giving priority attention to vulnerable and marginalized groups is one of the Covenant’s main intents, and a core obligation of states. Other official interpretations of the ICESCR supporting the obligation to prioritize vulnerable groups are stated in the Limburg Principles on the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1986), and The Maastricht Guidelines on Violations of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1997).44

Affirmative action to preferentially promote the achievement of rights by groups who are vulnerable because they have historically experienced discrimination is justified, so long as the preference is not permanent, and is removed once a group is no longer vulnerable. The ICERD states:

Special measures taken for the sole purpose of securing adequate advancement of certain racial or ethnic groups or individuals requiring such protection as may be necessary in order to ensure such groups or individuals equal enjoyment or exercise of human rights and fundamental freedoms shall not be deemed racial discrimination, provided, however, that such measures do not, as a consequence, lead to the maintenance of separate rights for different racial groups and that they shall not be continued after the objectives for which they were taken have been achieved.45

Similarly, the CESCR stated the following in General Comment 16 (under “Temporary Special Measures”):

The principles of equality and non-discrimination, by themselves, are not always sufficient to guarantee true equality. Temporary special measures may sometimes be needed in order to bring disadvantaged or marginalized persons or groups of persons to the same substantive level as others. Temporary special measures aim at realizing not only de jure or formal equality, but also de facto or substantive equality for men and women. However, the application of the principle of equality will sometimes require that States parties take measures in favour of women in order to attenuate or suppress conditions that perpetuate discrimination. As long as these measures are necessary to redress de facto discrimination, and are terminated when de facto equality is achieved, such differentiation is legitimate.46

States have the responsibility not only to strive to end intentionally discriminatory actions and structures, but also to strive to end de facto discrimination, that is, structural or institutional patterns resulting in, exacerbating, or perpetuating inequality in obstacles to realizing rights, regardless of intent. The ICERD states: “Each State Party shall take effective measures to review governmental, national and local policies, and to amend, rescind or nullify any laws and regulations which have the effect of creating or perpetuating racial discrimination wherever it exists.”47 Similarly, the CESCR’s General Comment 20 defined discrimination as:

any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference or other differential treatment that is directly or indirectly based on the prohibited grounds of discrimination and which has the intention or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise on an equal footing of [ICESCR] rights.”48

Gillian MacNaughton has noted examples of reports from the International Committee for Civil and Political Rights in which the issues singled out as manifesting discriminatory patterns involve underlying social inequality between groups; for example, the disproportionate representation of African Americans among homeless people in the US.49

Equality

The equality of all persons “in dignity and rights” can be seen as the basis for non-discrimination as well as for all human rights; this is paralleled by the basis for the concept of equity, which rests on valuing all persons equally.50 The operational definition of equality in the field of human rights — apart from equality before the law — has been much debated.51 The concept of equality has been no less contentious in the field of health equity. Equity and equality are seen by many as distinct, with equity potentially requiring inequality, that is, allocating more resources (including resources addressing social determinants as well as medical care) to those who need more. Two dimensions are often distinguished: horizontal equity, or equal resources for equal need, and vertical equity, or more resources for greater need; defining need can be challenging, however.52

Furthermore, in situations where a particular group of persons – for example, women, or people of a lower caste — is especially disenfranchised, a clear call for equality rather than equity may be essential, because some definitions of equity may leave too much room for interpretation. For example, more enfranchised groups may argue that the treatment of a disenfranchised group is “equitable,” given the latter’s best interests and proper role in society. In any case, equity cannot be assessed without measuring equality and inequality: progress toward greater equity is measured by reductions in health inequalities.

Other human rights principles with particular relevance for health equity: Progressive realization and the obligation to respect, protect, and fulfill rights

Human rights instruments acknowledge that governments, particularly in developing countries, often will be unable to immediately remove all obstacles to their populations’ realization of all rights, particularly the economic and social rights, and therefore require states to show good faith efforts at progressively moving toward that goal. Governments are obligated to ensure the immediate fulfillment of some rights (generally those prohibiting active infringements on rights), and, at least, to progressively take steps toward ensuring that all persons can realize all of their rights. Governmental obligation lies not only in not violating (that is, respecting) the rights of their populations, but also in protecting these rights against violations by other parties, and actively promoting the realization of rights by all persons.53

Health equity, human rights, and the role of social conditions in health

Foundational concepts of health equity, as defined here, reflect not only the ethical principle of distributive justice, but also core human rights principles, particularly nondiscrimination and equality, the indivisibility and interdependence of rights, the rights to a standard of living adequate for health; the right to education; and the right to the highest attainable standard of health. These human rights and principles strengthen the conceptual basis for health equity, supporting the definition of equity presented in this paper and elsewhere.54 The rights to education and to a standard of living adequate for health, along with the principle of the indivisibility of all rights, are of direct and explicit relevance to the link between social conditions and health, and thus make a particular contribution to the concept of health equity as one that requires equity in the distribution of the determinants of health, including social conditions.

The principle of nondiscrimination makes two major contributions, both to the conceptualization and measurement of health equity, and hence to health equity analysis. First, the relevant agreements regarding nondiscrimination provide a rationale for the obligation to give special attention to protecting and fulfilling the rights of particular social groups; namely, these groups’ vulnerability based on their history of experiencing greater obstacles to realization of equal rights. This is an important contribution because the rationale for affirmative action, or giving preferential attention to the disadvantaged, can be a contentious issue in discussions of equity, notwithstanding John Rawls’s widely accepted notion of the ethical obligation of societies to give priority to maximizing the opportunities for well-being of those who are disadvantaged.55 The obligation to actively promote and fulfill realization of rights is consistent with the concept that pursuing health equity entails striving to reduce potentially modifiable inequalities in health and its determinants, which put already socially disadvantaged groups at further disadvantage with respect to their health.

Another — and arguably even more substantial — contribution of human rights to health equity conceptualization, measurement, and analysis, is the (non-exhaustive) specification of social categories defining groups that are vulnerable because of discrimination and whose rights therefore deserve special protection and promotion. Those categories were incorporated, with minimal modification, into the proposed definition of health equity presented here: racial or ethnic group, skin color, religion, or nationality; socioeconomic resources or position (reflected by, for example, income, wealth, education, or occupation); gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, marital status, age, geography, disability, illness, political or other affiliation, or other characteristics systematically associated with discrimination or marginalization (exclusion from social, economic, or political opportunities). The appropriateness of many of these categories as warranting special protection from discrimination has been questioned at times. The ability to refer to human rights agreements, legally binding or not, on this subject is a tremendous resource (because such agreements represent international consensus on values). These human rights principles inform health equity measurement and analysis because analytic approaches are driven by the definitional concepts. For example, if the definitional concepts are accepted, they imply the need to measure inequalities in indicators of health and health determinants across groups with different levels of social advantage/disadvantage, within each of the specified categories (for example, by comparing more and less advantaged racial or ethnic groups, more and less educated groups, groups in more and less advantaged occupations, groups with and without disabilities, homosexuals and heterosexuals, women and men).

The “right to the highest attainable standard of health” contributes to the concept of health equity — with implications for measurement and analysis — by strengthening more egalitarian interpretations of that concept. It supports the notion that pursuing health equity requires striving to reduce inequalities in health by undertaking concerted actions to improve the health of disadvantaged groups as much as possible, thereby bringing them to the level of health experienced by the most socially advantaged groups — rather than simply achieving some minimal level of absence of disease. Concerning measurement and analysis, this concept implies that health equity comparisons should use a reference group (standard for comparison) that represents the highest standard, rather than a minimal or average level.

Similarly, basic concepts of health equity can greatly enrich human rights work, such as the need to address social as well as medical determinants of health by raising awareness and providing empiric support for that perspective from the growing knowledge base linking social conditions and health. The most important contribution that the field of health equity can make to human rights efforts is perhaps in the area of measurement. Health equity concepts and measurement approaches can indicate how to operationalize the concept of the right to the highest attainable standard of health in a way that lends itself to measurement; this is essential for monitoring compliance, but has been elusive. Using concepts from the field of health equity, the right to the highest attainable standard of health can be operationalized as equal opportunity to achieve the standard of health (that is, no greater obstacles to realizing rights) enjoyed by a society’s socially privileged persons such as, for example, those who are affluent, well educated, well accepted, politically influential, and from privileged families. That level of health should be biologically attainable by everyone, regardless of race, wealth, or other attributes reflecting social and economic advantage. It might also be noted that reverse causation — reduced income due to poor health — could concentrate individuals with unavoidably poor health, such as those with certain birth defects, among the less economically advantaged. The preponderance of evidence suggests, however, that although this can occur, reverse causation is unlikely to account for a major part of the observed links between wealth and health.56

Using the level of health enjoyed by the socially advantaged as a rough benchmark for the highest attainable standard of health, progressive realization of the right to health can therefore be monitored by examining whether inequalities in both health status and in the underlying determinants of health — including social conditions — are diminishing over time among social groups with different levels of social and economic advantage; the disadvantaged groups are those warranting special protection from discrimination. This could be an important tool in efforts for greater accountability for progress toward realizing the right to health.

Human rights and health equity also share some fundamental controversies: for example, whether rights (or equity) are achieved when the health and health determinants —including social conditions — of the disadvantaged are brought up to a minimal “decent” level, rather than to the highest possible level. The definition of health equity advanced here implies an ongoing commitment to closing the health gap between the disadvantaged and the most advantaged, as opposed to aiming for a lower level.57 Rawls’s concept supports this approach, as does the human rights language on the right to “the highest attainable standard of health.”58 Arguments for a more “minimum basic standards” approach, however, can be found in both fields. Whether the standard is the level of health enjoyed by the best-off or a lower level of health, both human rights and equity principles require that the closing of the gap is accomplished by what Margaret Whitehead and Göran Dahlgren have called “leveling up” — improving the health of the disadvantaged, rather than reducing the health of the best-off; this is consistent with the ethical principles of beneficence and non-malfeasance.59 Although both health equity and human rights principles call for giving special attention to improving the health and health determinants of the most disadvantaged, neither can specify the exact degree of priority that should be given to that objective, weighed against other legitimate priorities, including efficiency.

The areas of convergence and complementarity between human rights and health equity, thus, are substantial. Is there divergence as well? The clearest point of divergence is the nature of the primary realms they occupy, and its implications for action. While both fields have an ethical dimension, health equity operates entirely within the realm of ethics, without legal force. Ethical principles provide guidance on what persons, groups, and states should and should not do if they are righteous; however, there are no legal mechanisms for monitoring compliance with the ethical principle of justice. Human rights, by contrast, operates to a great extent in the realm of law and governmental policy; human rights instruments articulate what governments should — and should not — do, and internationally recognized bodies are mandated to monitor compliance. Legal enforcement of human rights is woefully inadequate. Furthermore, not all human rights are legally binding, and in any case, states are legally bound to respect, protect, and fulfill only those rights enumerated in agreements that they have actually ratified. For example, the United States has signed, but not ratified, the ICESCR, making the treaty only morally rather than legally binding on the US. In addition, the legal basis for human rights may be viewed at times as a potential weakness, if it results in exclusive reliance on the courts to redress injustice, bypassing the crucial step of supporting populations in mobilizing to protect and fulfill their rights through political action.

Notwithstanding these caveats, the legal nature of human rights concepts and instruments is a precious and unique resource. The basis of human rights in international agreements between authorized state representatives, whether legally binding or not, and whether universally enforced or not, is perhaps the most powerful contribution that human rights can make to health equity efforts. There are no official agreements, covenants, or conventions in the field of health equity which governmental leaders are called upon to sign and perhaps ratify. These principles may not always go as far as many proponents of equity and human rights would wish; however, they embody such important foundational principles for work on both equity and rights that their contribution is, nevertheless, of immeasurable importance. By now, all countries are at least signatories to one or more human rights agreements with direct or indirect implications for health equity and for the link between social conditions and health. Particularly given the significant areas of convergence between human rights and health equity on core values, these international agreements therefore have implications for protecting and promoting health equity as well as human rights. Despite ongoing violations, human rights agreements represent an overwhelming global consensus — across continents, nations, languages, levels of economic development, and, to some extent, political systems — on shared basic values that can be cited in initiatives to achieve greater equity. These agreements have been hammered out in discussions over years, sometimes decades, and captured in official documents witnessed by heads of state. As Mary Robinson, former President of Ireland and former United Nations Commissioner for Human Rights, has written,

Clearly, human rights cannot provide all the answers or make easier difficult public health choices concerning priorities and distribution of goods and services. But what other framework offers any detailed ethical, moral or legal guidance to policy-makers?60

The fields of human rights and health equity have different languages, perspectives, criteria, and tools for action. At the same time, they share several fundamental values, all of which center on the equal dignity and worth of all human beings. Both human rights and health equity efforts can be strengthened by growing awareness and understanding of the importance of social conditions for health. Both uphold the principle — although expressed in different ways — that health-promoting social conditions are an essential prerequisite for health. Without blurring distinctions, the two fields can enrich each other considerably, mutually reinforcing core concepts of each. In particular, the global consensus on values reflected by human rights agreements and norms represents a potentially powerful advocacy tool in struggles for greater equity. Human rights frameworks and principles can be used to support the conceptual basis for health equity, notably by providing a rationale for the specification of vulnerable groups whose rights require special protection and promotion, and thus informing analytic approaches to understanding health equity and its determinants. Correspondingly, applying concepts and measurement approaches from the field of health equity can strengthen efforts to protect and promote the right to the highest attainable level of health and, by extension, the right to the social conditions essential for health, by indicating how to operationalize these concepts for the purpose of measurement, which is essential for accountability. Ultimately, battles for human rights and health equity will not be won or lost solely based on the conceptual clarity and coherence of the arguments, the soundness of measurement methods, or the abundance of supporting data. These are, however, important resources for building societal consensus and arming advocates among and on behalf of the disenfranchised and marginalized.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge Sofia Gruskin, JD, who collaborated on earlier work on these issues (cited herein), on which this paper builds. I am solely responsible for any shortcomings of the content. I also wish to thank Karen Simpkins, MLS, and Susan Egerter, PhD, for their assistance with editing, and Karen Simpkins, MLS, Colleen Barclay, MPH, and Tabashir Sadegh-Nobari, MPH, for their assistance with the research for this paper.

Paula Braveman, MD, MPH, is Professor of Family and Community and Director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, USA. Her research has focused on conceptualizing, measuring, and understanding socioeconomic and racial/ethnic inequalities in health in the United States and globally.

Please address correspondence to Paula Braveman c/o Center on Social Disparities in Health, University of California, Box 0943, 3333 California Street, Suite 365, San Francisco, CA 94118–0943, email: braveman@fcm.ucsf.edu.

References

1. P. Braveman, “Health disparities and health equity: Concepts and measurement,” Annual Review of Public Health 27 (2006), pp. 167–194.

2. A. E. Yamin, “Shades of dignity: Exploring the demands of equality in applying human rights frameworks to health,” Health and Human Rights: An International Journal 11/2 (2009), pp. 1–18; P. Farmer, “Pathologies of power: Rethinking health and human rights,” American Journal of Public Health 89/10 (1999 ), pp. 1486–1496; M. Susser, “Health as a human right: An epidemiologist’s perspective on the public health,” American Journal of Public Health 83/3 (1993), pp. 418–426; L. London, “‘Issues of equity are also issues of rights’: Lessons from experiences in Southern Africa,” BMC Public Health 7/14 (2007), pp. 603–607; P. Hunt, “Missed opportunities: Human rights and the Commission on Social Determinants of Health,” Global Health Promotion Suppl 1 (2009), pp. 36–41; J. N. Erdman, “Human rights in health equity: Cervical cancer and HPV vaccines,” American Journal of Law and Medicine 35 (2009), pp. 365–387; G. MacNaughton, “Untangling equality and non-discrimination to promote the right to health care for all,” Health and Human Rights: An International Journal 11/2 (2009), pp. 47–63; T. Evans, “A human right to health?” Third World Quarterly 23/2 (2002), pp. 197–216; P. Braveman and S. Gruskin, “Poverty, equity, human rights and health,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 81 (2003a), pp. 539–545; P. Braveman and S. Gruskin, “Defining equity in health,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 57 (2003b), pp. 254–258; S. Gruskin and P. Braveman, “Addressing social injustice in a human rights context,” in B. Levy and V. W. Sidel (eds), Social injustice and public health (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 405–417; P. Braveman, and S. Gruskin, “Health equity and human rights: What’s the connection?” in D. Fox and A. Scott-Samuel, (eds), Human rights, equity, and health: Proceedings from a meeting of the Health Equity Network held at the London School of Economics. March 28, 2003 (London: The Nuffield Trust, 2004); and Braveman (see note 1).

3. World Health Organization, “Health and human rights.” Available at http://www.who.int/hhr/en/.

4. Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH), Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health: Final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health (Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2008). Available at http://www.who.int/social_determinants/final_report/en.

5. D. Black, J. N. Morris, C. Smith, et al., Inequalities in health: The Black Report: The health divide (London: Penguin Books, 1988); Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, OECD health data 2009: Frequently requested data. Available at http://www.oecd.org/document/ 16/0,3343,en_2649-34631_2085200_1_1_1_1,00.html; P. A. Braveman, C. Cubbin, S. Egerter, et al., “Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: What the patterns tell us,” American Journal of Public Health 100/S1 (2010), pp. S186–S196; and N. E. Adler and D.H. Rehkopf, “US disparities in health: Descriptions, causes, and mechanisms,” Annual Review of Public Health 29 (2008), pp. 235–252.

6. Commission on Social Determinants of Health (see note 4); N. E. Adler and J. Stewart, “Health disparities across the lifespan: Meaning, methods, and mechanisms,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1186 (2010), pp. 5–23; Braveman (see note 1); A. Steptoe and M. Marmot, “The role of psychobiological pathways in socio-economic inequalities in cardiovascular disease risk,” European Heart Journal 23/1 (2002), pp. 13–25; Adler and Rehkopf (see note 5); B. S. McEwen and P. J. Gianaros, “Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: Links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1186 (2010), pp. 190–222; G. W. Evans and P. Kim, “Multiple risk exposure as a potential explanatory mechanism for the socioeconomic status-health gradient,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1186 (2010), pp. 174–189; and K. A. Matthews, L. C. Gallo, and S. E. Taylor, “Are psychosocial factors mediators of socioeconomic status and health connections?” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1186 (2010), pp. 146–173.

7. Commission on Social Determinants of Health (see note 4).

8. B. S. McEwen, “Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 840 (1998), pp. 33–44; McEwen and Gianaros (see note 6); Steptoe and Marmot (see note 6); T. E. Seeman, B. H. Singer, J. W. Rowe, et al., “Price of adaptation: Allostatic load and its health consequences; MacArthur studies of successful aging,” Archives of Internal Medicine 157/19 (1997), pp. 2259–2268; P. C. Strike and A. Steptoe, “Psychosocial factors in the development of coronary artery disease,” Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 46/4 (2004), pp. 337–347; and S. C. Segerstrom and G. E. Miller, “Psychological stress and the human immune system: A meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry,” Psychological Bulletin 130/4 (2004), pp. 601–630.

9. Ibid.

10. McEwen (see note 8); McEwen and Gianaros (see note 6); Steptoe and Marmot (see note 6); Seeman et al. (see note 8); and Matthews et al. (see note 6).

11. Ibid.

12. J. P. Shonkoff, W. T. Boyce, and B. S. McEwen, “Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: Building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention,” Journal of the American Medical Association 301/21 (2009), pp. 2252–2259; G. Guo and K. M. Harris, “The mechanisms mediating the effects of poverty on children’s intellectual development,” Demography 37/4 (2000) pp. 431–447; M. J. Farah, L. Betancourt, D. M. Shera, et al., “Environmental stimulation, parental nurturance and cognitive development in humans,” Developmental Science 11/5 (2008), pp. 793–801; and D. A. Hackman and M. J. Farah, “Socioeconomic status and the developing brain,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 13/2 (2009), pp. 65–73.

13. C. Hertzman and M. Wiens, “Child development and long-term outcomes: A population health perspective and summary of successful interventions,” Social Science and Medicine 43/7 (1996), 1083–1095; L. A. Karoly, M. R. Kilburn, and J. S. Cannon, Early childhood interventions: Proven results, future promise (Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation, 2005); and Shonkoff et al. (see note 12).

14. F. K. Mensah and J. Hobcraft, “Childhood deprivation, health and development: Associations with adult health in the 1958 and 1970 British prospective birth cohort studies,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 62/7 (2008), pp. 599–606; C. Hertzman, “The biological embedding of early experience and its effects on health in adulthood,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 896 (1999), pp. 85–95; and Shonkoff et al. (see note 12).

15. S. Egerter, P. Braveman, T. Sadegh-Nobari, et al., Education matters for health (Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2009).

16. K. E. Pickett and M. Pearl, “Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: A critical review,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 55/2 (2001), pp. 111–122; and A. V. Diez Roux, S. S. Merkin, D. Arnett, et al., “Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease,” New England Journal of Medicine 345/2 (2001), pp. 99–106.

17. G. W. Evans and E. Kantrowitz, “Socioeconomic status and health: The potential role of environmental risk exposure,” Annual Review of Public Health 23 (2002), pp. 303–331; M. Franco, A. V. Diez Roux, T. A. Glass, et al., “Neighborhood characteristics and availability of healthy foods in Baltimore,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 35/6 (2008), pp. 561–567; A. Steptoe and P. J. Feldman, “Neighborhood problems as sources of chronic stress: Development of a measure of neighborhood problems, and associations with socioeconomic status and health,” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 23/3 (2001), pp. 177–185; L. Franzini, M. N. Elliott, P. Cuccaro, et al., “Influences of physical and social neighborhood environments on children’s physical activity and obesity,” American Journal of Public Health 99/2 (2009), pp. 271–278; L. H. McNeill, M. W. Kreuter, and S. V. Subramanian, “Social environment and physical activity: A review of concepts and evidence,” Social Science and Medicine 63/4 (2006), pp. 1011–1022; and Pickett and Pearl (see note 16).

18. A. Singh-Manoux, N. E. Adler, and M. G. Marmot, “Subjective social status: Its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study,” Social Science and Medicine 56 (2003), pp. 1321–1333; D. Kim, A. V. Diez Roux, C. I. Kiefe, et al., “Do neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation and low social cohesion predict coronary calcification? The CARDIA study,” American Journal of Epidemiology 172/3 (2010), pp. 288–298; and M. Pearl, P. Braveman, and B. Abrams, “The relationship of neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics to birthweight among five ethnic groups in California,” American Journal of Public Health 91/11 (2001), pp. 1808–1814.

19. Commission on Social Determinants of Health (see note 4).

20. Documents and tools related to the Commission effort, including the Foundation’s rationale for establishing the Commission and a framework for seeking solutions to the identified problems, Commission recommendations, and a series of issue briefs and other materials, are available at http://www.commissiononhealth.org/ Publications.aspx. See also, P. Braveman and S. Egerter, Overcoming obstacles to health: Report from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to the Commission to Build a Healthier America (Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2008); and W. Miller, P. Simon, and S. Maleque, Beyond health care: New directions to a healthier America (Washington, DC: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Commission to Build a Healthier America, 2009).

21. Braveman and Egerter (see note 20).

22. G. Rose, The strategy of preventive medicine (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1993).

23. Braveman (see note 1).

24. S. Harper and J. Lynch, Methods for measuring cancer disparities: Using data relevant to Healthy People 2010 cancer-related objectives (Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2005); E. R. Pamuk, “Social class inequality in mortality from 1921 to 1972 in England and Wales,” Population Studies 39/1 (1985), pp. 17–31; and A. Wagstaff, P. Paci, and E. van Doorslaer, “On the measurement of inequalities in health,” Social Science and Medicine 33/5 (1991), pp. 545–557.

25. Braveman (see note 1); P. A. Braveman, S. A. Egerter, C. Cubbin, and K. S. Marchi, “An approach to studying social disparities in health and health care,” American Journal of Public Health 94/12 (2004), pp. 2139–2148; P. Braveman, “Monitoring equity in health and healthcare: A conceptual framework,” Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition 21 (2003), pp. 273–287; J. P. Mackenbach and A. E. Kunst, “Measuring the magnitude of socio-economic inequalities in health: An overview of available measures illustrated with two examples from Europe,” Social Science and Medicine 44/6 (1997), pp. 757–771; A. Wagstaff, P. Paci, and E. van Doorslaer, “On the measurement of inequalities in health,” Social Science and Medicine 33 (1991), pp. 545–557; S. Harper,J. Lynch, S. Meersman, et al., “An overview of methods for monitoring social disparities in cancer with an example using trends in lung cancer incidence by area-socioeconomic position and race-ethnicity, 1992–2004,” American Journal of Epidemiology 167/8 (2008), pp. 889–899; Harper and Lynch (see note 24); and S. Harper, and J. Lynch, Selected comparisons of measures of health disparities: A Review using databases relevant to Healthy People 2010 cancer-related objectives (Bethesda, Maryland: National Cancer Institute, 2007).

26. Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), G.A. Res. 217A (III) (1948). Available at http://www.un.org/Overview/rights.html [hereinafter UDHR]; International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI) (1966). Available at http://www2.ochcr.org/english/law/ccpr.htm [hereinafter ICCPR]; International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI), Art. xx. (1966). Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/cescr.htm [hereinafter ICESCR]; The Limburg Principles on the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, UN ESCOR, 4th Comm, 43rd sess, Annex, UN Doc E/CN.4/1987/17 (1987) [hereinafter Limburg]; and the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), Maastricht Guidelines on Violations of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 26 January 1997. Available at http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/48abd5730.html [hereinafter Maastricht].

27. International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination [hereinafter ICERD], G.A. Res. 2106A (XX) (1965). Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/ratification/2.htm [hereinafter ICERD].

28. J. W. Nickel, “How human rights generate duties to protect and provide,” Human Rights Quarterly 15/1 (1993), pp. 77–86.

29. UDHR (see note 26), Art. 25.1.

30. M. Minkler, E. Fuller-Thomson, and J. M. Guralnik, “Gradient of disability across the socioeconomic spectrum in the United States,” New England Journal of Medicine 335 (2006), pp. 695–703.

31. Braveman et al. (see note 5).

32. Commission on Social Determinants of Health (see note 4).

33. ICESCR (see note 26), Article 13.

34. A. Sen , Development as freedom (New York: Anchor Books, 2000), pp. 74–110.

35. J. P. Ruger, “Health and social justice,” Lancet 364/9439 (2004), pp. 1075–1080; T. Goodman, “Is there a right to health?” The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 30/6 (2005), pp. 643–662; and A. Hendriks and B. Toebes, “Towards a universal definition of the right to health?” Medicine and Law 17/3 (1998), pp. 319–332.

36. S. Gruskin and D. Tarantola. “Health and human rights,” in R. Detels and R. Beaglehole (eds), Oxford textbook on public health (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 312–335; P. Hunt and G. Backman, “Health systems and the right to the highest attainable standard of health,” Health and Human Rights: An International Journal 10/1 (2008), pp. 81–92; and M. Torres, “ The human right to health, national courts and access to HIV/AIDS treatment: a case study from Venezuela,” Chicago Journal of International Law 3 (2002), pp. 105–114.

37. C. Chinkin, “Health and human rights,” Public Health 120 (2006), pp. 52–60; and Goodman (see note 35).

38. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights [hereinafter CESCR], General Comment No. 14, The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, UN Doc. No. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000). Available at http://www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/0/40d009901358b0e2c1256915005090be?Opendocument.

39. Ibid., Item 4 in Introduction.

40. Ibid., Item 11 in Introduction.

41. A. E. Yamin, “The right to health under international law and its relevance to the United States,” American Journal of Public Health 95/7 (2005), pp. 1156–1161.

42. UDHR (see note 26), Article 2; ICCPR (see note 26); and ICESCR (see note 26).

43. CESCR, General Comment No. 20, Nondiscrimination in Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, UN Doc. No. E/C.12/GC/20 (2009), para. 19. Available at http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/4a60961f2.html.

44. Limburg (see note 26); and Maastricht (see note 26).

45. ICERD (see note 27), Art. 1(14).

46. CESCR, General Comment No. 16, The Equal Right of Men and Women to the Enjoyment of All Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, UN Doc. No. E/C.12/2005/4 (2005). Available at http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/43f3067ae.html.

47. ICERD (see note 27), Art. 2c. Emphasis added.

48. CESCR, General comment No. 20 (see note 43). Emphasis added.

49. MacNaughton (see note 2), p. 51.

50. UDHR (see note 26).

51. Yamin (see note 2); MacNaughton (see note 2); A. Buchanan, “Equality and human rights,” Politics, Philosophy and Economics 4/1 (2005), pp. 69–90.

52. Wagstaff et al. (see note 24)

53. Yamin (see note 2); B. M. Meier, “Advancing health rights in a globalized world: Responding to globalization through a collective human right to public health,” Journal of Law and Medical Ethics 35/4 (2007), pp. 545–555, 511; A. Hendriks, “The right to health in national and international jurisprudence,” European Journal of Health Law 5/4 (1998), pp. 389–408; and M. Stuttaford, “Balancing collective and individual rights to health and health care,” Law, Social Justice and Global Development Journal (2004/1) [online]. Available at http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/law/elj/lgd/2004_1/stuttaford/.

54. The Secretary’s Advisory Committee on National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020, Phase I report: Recommendations for the framework and format of Healthy People 2020 (Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2008). Available at http://www.healthypeople.gov/hp2020/advisory/PhaseI/PhaseI.pdf; Braveman (see note 1); and Braveman and Gruskin (2003b, see note 2).

55. J. Rawls, A Theory of Justice (Cambridge: Belknap/Harvard University Press, 1971).

56. I. Kawachi, N. Adler, and W. Dow, “Money, schooling, and health: Mechanisms and causal evidence,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1186 (2010), pp. 56–68; and P. Muennig, “Health selection vs. causation in the income gradient: What can we learn from graphical trends?” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 19/2 (2008), pp. 574–579. Available at http://www.pceo.org/pubs/JHCPU.pdf.

57. Braveman (see note 1).

58. Rawls (see note 55).

59. M. Whitehead and G. Dahlgren, Leveling up, part 1: Concepts and principles for tackling social inequalities in health (Copenhagen: World Health Organization, 2006).

60. M. Robinson, “The value of a human rights perspective in health and foreign policy,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 85/3 (2007), pp. 241–242.