Alicia Ely Yamin

Health and Human Rights 11/2

Published December 2009

The law, in its majestic equality, forbids the rich as well as the poor from sleeping under bridges.

— Anatole France

Abstract

The foundational principle of human rights is that all human beings are equal in rights, dignity, and worth. Yet we live in a world ravaged by social inequalities both within and between countries, which have profound implications for the distribution of population health as well as the unequal enjoyment of economic and social rights and of human rights generally. It is far from clear that we have a consensus in the human rights community about which inequalities in health constitute inequities or how egalitarian a society must be to conform to the requirements of a social order in which all human rights can be realized. Further, the conversations in the world of human rights have largely been divorced from those in the worlds of development and public health. In this article, I attempt to bring those two conversations together. I first set out how concepts of formal and substantive equality and non-discrimination are defined under international law and might be applied in practice to questions we face in public health today. I argue that the application of these concepts is far from formulaic; interpretations of equality and non-discrimination necessarily reflect deeply held understandings about justice, power, and how we are the same and different from one another. I then explore how far a human rights framework can guide us in terms of some of these underlying questions in health and development policy, particularly in relation to how much priority should be given to the worst off in society, what kind of equality we should be seeking from a human rights perspective, and how we should evaluate who is worst off in terms of health. In conclusion, I argue that the great power of applying a human rights framework to health lies in denaturalizing the inequalities that pervade our societies and our world, and in establishing that all people — by virtue of being human — have both a claim for redress when they are treated unfairly and a right to participate in determining what equity and equality require in a given context.

Introduction

The foundational principle of human rights is that all human beings are equal in rights, dignity, and worth.1 Health is a human right in and of itself, and, at the same time, the condition of health reflects the enjoyment of many other human rights. Thus, in a human rights framework, we cannot merely be concerned with inequalities in health care. Rather we need to confront the fact that more than 60 years after the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was unanimously proclaimed, we live in a world ravaged by inequalities in power, money, and resources both within and between countries, which have profound implications for the distribution of population health as well as the unequal enjoyment of economic and social rights and of human rights generally.2 As Sir Michael Marmot, Chair of the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health has stated, “The fact that holders of such power may relinquish it with reluctance must not deter us from pursuing what is just. The fact that…social injustice is a matter of life and death needs continuously to be brought to the fore.”3

Moreover, these inequalities grew even as economies expanded at record rates in the second half of the 20th century. In China and Brazil, for example, GDP has grown an average of 7.9% and 4.4% per year, respectively, since the 1960s, but the gaps between the rich and poor have also grown.4 In India, despite consistent economic growth of over 5% annually over the same period, ActionAid recently reported that a shocking 47% of children under six face chronic malnutrition.5 Babu Matthew, country director for ActionAid India, stated at the report’s release, “The dark side of India’s economic growth has been that the excluded social groups have been further marginalised, compounding their hunger, malnutrition and even leading to starvation deaths.”6 Further, between-country inequality over the last fifty years grew at an even greater pace than within-country inequality.7 If economic growth is not a panacea, economic contraction — such as the current global recession — unquestionably compounds the dire situation faced by those who are among the worst off on the planet.8

In public health, there is increasing evidence that social inequality, not just absolute deprivation, is bad for our health.9 Among rich countries, there is considerable evidence that the more unequal countries produce worse health and quality-of-life outcomes, and the steeper the gradient of the social ladder, the worse the outcomes are in terms of life expectancy, infant mortality, crime rates, and a host of other indicators.10 Thus, the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health has suggested that addressing health inequalities requires a two-pronged approach that includes 1) reducing exposures and vulnerabilities linked to position on the social ladder and 2) reducing the social gradient itself.11

Historically, human rights law has been most concerned with identifying those who are consistently kept low on the proverbial ladder and with the social relations — such as gender, race, and caste — that keep them in place. In so doing, human rights has highlighted that poverty is not only about lack of money; it is also about discrimination and disempowerment. It is invariably women, racial and ethnic minorities, disabled persons, and other marginalized populations who are not only disproportionately represented among the most economically disadvantaged but also consequently whose effective enjoyment of rights is most impaired.12 Further, in a human rights framework, the ways in which certain people are kept low on the ladder represent not just a tragedy or inherent vulnerability but active processes of exclusion and marginalization, for which there should be accountability and redress.13

Increasingly, scholars and activists from the human rights community have argued — pointing to obligations regarding economic and social rights, including health rights — that it should not be the case that those on the lowest rungs face not having clean running water, sanitation, nutrition, access to health care or other basic building blocks of human dignity, and in some cases that poverty itself is a violation of human rights.14

However, even if we are able to convert the rhetoric of rights into effective strategies, establishing a right to freedom from poverty or to a minimum essential level of housing, health care, education, and the like all relate to combating absolute deprivation; equality is a matter of relative deprivation. It is far from clear that we have a consensus in the human rights community about which inequalities in health constitute inequities or how egalitarian a society must be before all human rights, including health, can be realized.15 Further, conversations about equality demands in the human rights field have largely been divorced from discussions of equality and equity in public health.16

In this article, I attempt to bring those conversations together, at least partially. In the first section, I set out how concepts of formal and substantive equality and non-discrimination are defined under international law, and how they might be applied in practice to questions we face in public health today. I argue that the application of these concepts is far from formulaic; that is, interpretations of equality and non-discrimination necessarily reflect deeply held understandings about justice and power and about what being fully human really means. The second part of the article explores some of the contested issues underlying these legal concepts by asking: What level of priority does human rights require to be given to the worst off in society? What kind of equality should we seek from a human rights perspective? And how do we judge when one situation is worse than another? My aim is not to attempt to outline a monolithic “human rights approach” to equality in health. On the contrary, I hope to map out some of the questions and challenges that I believe we need to confront together from our different disciplinary perspectives if human rights approaches are to be meaningfully incorporated into health and development practice.

Non-discrimination and equality under international law

Under international law, health, including but not limited to health care, is considered a right. Consequently, even where we may tolerate many other inequalities, inequalities in health care are of special concern because such care is not merely another commodity to be allocated by the market.17 Moreover, as shocking and inhumane as inequalities in health care are, as the late Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. stated, inequalities in social determinants of health are undoubtedly an even greater influence on the distribution of well-being in a society.18 Therefore, discrimination and inequalities in patterns of education, housing, access to employment, and the like are also relevant for rights-based approaches to equality in health.

As is evident from the other Critical Concepts articles in this issue, the concept of equality and its relation to non-discrimination is complex — and comparative. Determining what differences should be taken into account between individuals and populations and in what ways — in short, what is fair — is not only controversial but speaks to deep-seated assumptions about us as human beings, as individuals who are simultaneously embedded in and derive identity from the multiple groups to which we belong. Nowhere is it more evident than in the evolution and dysjunctures of equality theory — at both international and national levels — that rights are both tools and sites of struggle over fundamental questions about what makes us the same and what makes us different from one another and about the spaces between us.

Unpacking non-discrimination

Under international law, human rights, including the right to health and to such social determinants as education and housing, are to be guaranteed “without discrimination of any kind as to race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.”19 “Other status” has been understood to include characteristics such as caste, health status, disability, and sexual identity. Non-discrimination is an explicit right under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); however, under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), non-discrimination is not a right but is a cross-cutting principle. Therefore, in most United Nations (UN) discourse, it is accepted as a “cross-cutting norm,” which includes both dimensions.

In its recently issued General Comment 20, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ESC Rights Committee) defined discrimination as “any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference or other differential treatment that is directly or indirectly based on the prohibited grounds of discrimination and which has the intention or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of [ICESCR] rights.”20 Thus, discrimination as prohibited under the ICESCR may be direct or indirect, in that a law or policy that appears neutral on its face can have a disproportionate impact upon certain groups.21 For example, a health insurance scheme based upon formal employment may indirectly discriminate against women who tend disproportionately to be in the informal sector.

Under international law, health status and disability are “prohibited grounds” of discrimination. Indeed, much early work in the field of health and human rights was devoted to understanding and preventing discrimination against people living with HIV.22 As discussed below, human rights law calls for going beyond abolishing de jure discrimination, which is clearly insufficient. Although UNAIDS reported in 2008 that 67% of countries had laws or regulations that protect people living with HIV from discrimination, in practice such persons face differing degrees of discrimination, stigma, and exclusion in every country.23 Similarly, as Jonathan Burns describes in this issue, “substantive inequality and discrimination characterize [both] the manifestation and experience of mental disability in society as well as the provision of mental health care.”

The notion that discrimination must be “based on” something prohibited in order to “count” as discrimination has been criticized. Gillian MacNaughton argues in this issue that determining whether differential treatment occurs because of a specific trait can be complicated and may pose undue burdens of proof. There is a tension in international human rights law, as well as constitutional law in many countries, between human status (group based) and human treatment (individual). MacNaughton argues for individual equality; similarly, Larry Temkin has asserted elsewhere that “if it is bad for one person to be worse off than another through no fault of her own, this should be so whether or not they happen to be lumped together as members of the same group.”24 And of course it is not always true that inequality within a group matters less than between groups.

On the other hand, as Catharine MacKinnon has written, “group membership does not simply distinguish humans; it is part of being human.”25 Focusing on individual as opposed to group rights may not prove fruitful in achieving meaningful empowerment of people from disadvantaged groups; factors that allow people to convert resources into the effective enjoyment of the rights to health, education, or housing generally need to be dealt with structurally. In addressing issues such as race-based residential segregation, the task is decidedly more complex than aggregating individual housing subsidies to “equalize” collective groups. Programs based on equalizing individuals, such as through cash transfers, can at times preserve and legitimate structural inequalities. Indeed, the 2000 World Health Report’s approach to monitoring health inequalities between ungrouped individuals has been roundly criticized for failing to show the deleterious effects of neoliberal economic policies on certain disadvantaged groups.26

In practice, the UN treaty-monitoring committees have generally adopted a flexible approach to non-discrimination, examining treatment of individuals, groups of individuals, and collectivities. A committee might examine, for instance, whether people of a similar group receive similar treatment and then compare it to treatment of other groups in society rather than requiring inordinate evidence regarding the basis for discrimination. For example, the ESC Rights Committee has called for “the disaggregation of health and socio-economic data according to sex [as] essential for identifying and remedying inequalities in health,” and de facto disparities between women and men have been sufficient for ESC Rights Committee and CEDAW to conclude that there is evidence of discrimination with respect to women’s health.27 Similarly, with respect to race, which international law understands as a social construct and not a biological determination, disparities have been sufficient for the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) to call for affirmative actions to ensure substantive equality.28 General Comment 20 appears to enshrine this approach to group disadvantage as a comparative concept that is open ended and evolves with changes in social reality.

Nonetheless, using the concept of non-discrimination to eliminate differential treatment based on income and wealth poses particular challenges. In some cases, distinctions would appear to be clear. For example, in contrast to US domestic law, an equal right to health under international law would require that access to abortion not be dependent upon a woman’s ability to pay for it.29 And as MacNaughton notes, two-tiered health systems such as Colombia’s — which distinguish between those formally employed and those earning less than a given minimum in setting differential benefit packages — should be seen as running afoul of non-discrimination provisions under international law.

But how far might the concept of non-discrimination be applied to wealth-based differentiations relating to health care access or background social conditions? For example, can we consider user fees or premiums that are uniform across incomes to constitute discrimination against poor people? Arguably yes. In General Comment 14, the ESC Rights Committee stated that

health facilities, goods, and services must be affordable for all. Payment for health care services, as well as services related to the underlying determinants of health, must be based on the principle of equity, ensuring that these services, whether privately or publicly provided, are affordable for all, including socially disadvantaged groups. Equity demands that poorer households should not be disproportionately burdened with health expenses as compared to richer households.30

Here, equity is used in the common law legal sense to mean justice administered according to fairness as contrasted with strictly formulated rules. Thus, uniform fees that pose unduly high burdens on the poor violate equity principles; arguably they may also substantively discriminate against certain poor people on the basis of their economic and social situation.31

The challenge of defining discrimination is even further complicated by the fact that differentiation based on prohibited grounds is not always unreasonable. For example, General Comment 20 states that “age” falls under “other” prohibited grounds of discrimination in several contexts, referring both to old age and to young age. Yet advanced age is used as a criterion for greatly increasing insurance premiums in some health systems that are based upon private insurance.32 Age also factors into priority setting in allocating scarce interventions.33

In a rights framework, I would argue that the latter is probably permissible, while the former is not. That is, if we accept that health and health care are of special moral importance — as we must if we assert them as rights — then by definition access to care cannot be set solely by the market.34 Just as women of reproductive years have greater health needs than men, so too do elderly people. And actuarial fairness — determining payment according to the level of risk faced — is not the equivalent of fairness based on an equal right to care.

On the other hand, if we are allocating scarce interventions or services — whether a transplant or a vaccine in limited supply — a plausible “fair innings” argument can be made that younger people have a greater claim because they are worse off if they die young than older people who are closer to or have surpassed a normal life span.35 Age does not seem a sufficient basis upon which to allocate such resources or interventions, but it does seem one that is ethically relevant to consider.36 An adequate rights framework must take account of intergenerational equity including the equal opportunity of younger people to live as long as older people already have.37

Formal equality: Connections between equality and universality

Echoing the understanding of State obligations under other treaties, General Comment 20 clarifies that States are required to eliminate both formal and substantive discrimination, which are based on the principles of formal and substantive equality, respectively.38 A claim for formal equality is a claim for equal treatment in relation to another individual or group and not a claim in relation to a particular outcome. Individuals or groups that are alike should be treated alike, according to their actual characteristics that are relevant, rather than assumptions or prejudices. For example, the Colombian Constitutional Court found that requiring people in de facto unions to be together for two years before being able to access health benefits under their partner’s employment was discriminatory because it was not required of unions formed by a legal marriage.39

Formal equality has historically been a central goal of human rights struggles. From anti-slavery to civil rights, from women’s suffrage to undocumented migrants’ movements, these struggles have reconfigured our socially constituted understanding of who is fully human and therefore possesses all of the dignity and legal rights accorded to those already recognized as full human beings. Indeed law itself, as Scott Burris and others have written, is a social determinant of health, acting to influence socioeconomic status as well as shaping and perpetuating stereotypes, institutions, and behaviors.40 For example, Uganda’s current proposals to further criminalize homosexuality — which its existing laws currently call “carnal knowledge against the order of nature” — illustrate how laws can naturalize particular stereotypes.41 When laws change — as happened with the recent Indian Supreme Court’s finding that the anti-sodomy statute was unconstitutional — they inscribe a new understanding not just of others as fully human, but also of what that means in turn for how we understand what being human means.42

Formal equality implies that the right to health, like all rights, is only meaningful if its content can be universally provided. When a court enforces a right to a given treatment or service, it should be something that at a minimum can be provided to everyone who is similarly situated. Part of the critique Octavio Ferraz makes in this issue with regard to the way that courts function in Brazil relates to the failure to consider the ability to universalize care; this failure, he argues, leads to perverse decisions. Arguably, this approach in Brazil, where the courts take thousands of cases every year regarding health claims, results in increasing inequality (and inequity) because the medical care decisions are allocated on a first-come first-served basis.43 Ferraz uses several measures to argue that “first-come first-served” favors people who are relatively better off financially, who are better informed, and who know their rights and are prepared to claim them — morally irrelevant criteria for determining who gets health benefits.

Similarly in Colombia, before the Constitutional Court issued a structural judgment in 2008 regarding the health system, the Court was criticized for granting extremely expensive medical care, irrespective of the possibility of universalizing the given treatment or service. In an influential concurrence in a 2004 case (T 654/04), Justice Rodrigo Uprimny suggested that

[t]he Court has not asked itself whether a given treatment is universalizable, whether it can be conceded to everyone in similar circumstances. By not posing that question, the jurisprudence of the Court runs the risk that, in the name of equality and the realization of social rights, it can provoke profound inequalities, as the treatment can be so costly as not to be provided to all who need it. Thus the judicial decision would be sanctioning [not a right, but] a privilege, which runs counter to the principle of equal treatment.44

We should note that judicial decisions have led to policy changes that have universalized access to a number of treatments in both Brazil and Colombia, as well as elsewhere. Yet if access to courts becomes an accepted precondition to accessing adequate care, the impacts could profoundly undermine not only formal equality, but also substantive equality.

Substantive equality: What counts when we are measuring fairness

Formal legal equality, while important, is often radically inadequate to achieve equal enjoyment of economic and social rights, including health, because of significant historically determined differences in circumstances among population groups. As Burns suggests, formal equality can give “the illusion that all are equal and that fairness exists, without addressing underlying inequalities in power, access, and socioeconomic and political circumstances.” Prohibitions on substantive discrimination therefore call for adopting “measures to prevent, diminish and eliminate the conditions or attitudes which cause substantive or de facto discrimination.”45 Thus, the question in achieving substantive equality is not how to treat people in the same way but what is required for people in fundamentally different circumstances to actually have equal enjoyment of their rights.

For example, the Convention to Eliminate all Forms of Discrimination against Women asserts that

[n]otwithstanding the [obligation of States Parties to take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in the field of health care in order to ensure, on a basis of equality of men and women, access to health care services,] States Parties shall ensure to women appropriate services in connection with pregnancy, confinement and the post-natal period, granting free services where necessary, as well as adequate nutrition during pregnancy and lactation.46

That is, the biological differences between men and women call for different sets of goods and services in order for women to be genuinely treated equally with respect to access to health care. To treat men and women in a uniform manner would itself constitute substantive discrimination.47

But substantive equality is not just a matter of recognizing that biological difference implies differential needs. International law goes beyond domestic law in many jurisdictions in recognizing that achieving substantive equality may require adopting temporary or permanent positive measures — for example with respect to racial and ethnic minorities, women, persons from scheduled and lower castes, and persons with disabilities — to combat the constraining effects of socially constructed circumstances.48 For example, under the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Disability Convention), discrimination includes the “denial of reasonable accommodation,” which is defined as “necessary and appropriate modification and adjustments not imposing a disproportionate or undue burden, where needed in a particular case, to ensure to persons with disabilities the enjoyment or exercise on an equal basis with others of all human rights and fundamental freedoms.”49

What constitutes “reasonable accommodations” and “disproportionate or undue burden” is highly contested. For example, in a case decided under Canadian law before the Disability Convention entered into force, the Canadian Supreme Court determined that the government’s failure to provide for sign-language interpreters when hearing-impaired people receive health care infringes the equality guarantee in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.50 Yet the majority of cases brought under the Canadian Charter to secure public funding for a specific health benefit have not prevailed in Canadian courts. When such claims have not prevailed, in Canada and elsewhere, the claim has often been interpreted as relating to a benefit that the law has not conferred — as something different and “extra” — rather than as something that enables substantively equal access to a benefit that the law has already recognized.51

Enforcing the right to health has led at times to judicial decisions that could foreseeably produce greater de facto inequalities because they fail to consider underlying asymmetries of money, resources, and social power beyond the health sector. One example, the Chaoulli decision reached by the Canadian Supreme Court, which MacNaughton mentions, where the Court upheld a challenge to legislation in Quebec — legislation substantially similar to that in a number of other provinces — that prohibited private insurance for medically necessary hospital and physician services. The Court agreed with the appellants, who claimed that the prohibition deprived them of access to health services that are not subject to the long waiting times of the public Medicare system, and that such deprivation violated their rights under both the Canadian and Quebec Charters.52 Aeyal Gross has cited fears that the decision would “result in the possible creation of a two-tier Charter rights structure [that] rather than guaranteeing a right to publicly funded health care guarantees a right to buy, if one is able, private insurance covering ‘medically necessary’ services.”53 Fortunately, five years after the case it appears not to have substantially undermined Medicare or the fundamental principle that there should be equal access to essential care based on need, primarily because the government reacted to the judgment by investing increased funds in the public system and sharply curtailing waiting times for everyone.

However, the executive branch cannot always be relied upon to react to judicial decisions by swiftly enacting progressive policies and increasing investment. In his critique of the role of courts in Brazil, Ferraz argues for the need to consider the overall impacts on equality in society. That is, he suggests, it is not only that the court system operates according to morally irrelevant criteria in determining who gets scarce health care resources — who has and acts upon access to justice — and therefore violates formal equality principles. But also, he argues, this first-come first-served system is likely to be increasing substantive inequalities when set against a backdrop of gross disparities in wealth, power, and education in Brazilian society.54 Similarly, Rodrigo Uprimny argued in the Colombian context that even if a specific treatment were universalizable, conceding treatments beyond what was already budgeted in the social insurance scheme could distort other financing for public health programs (such as vaccination programs) that would benefit greater numbers of people, thereby promoting greater substantive inequalities.55

In short, the “entanglement” — to use MacNaughton’s term — of non-discrimination and equality seems to follow inextricably from the fact that discrimination is inherently an empty concept without reference to the messy and competing ideals that underlie equality. International law has evolved in the metrics used to consider social disadvantage and to adduce discrimination. National judicial decisions regarding the right to health and other rights often turn on how the political branches of government justify treating different people who are similarly situated differently, or for treating differently situated people as though they were the same. However, the equality implications of granting access to specific health care goods and services cannot be divorced from the equality considerations regarding health system financing and whether care can be universalized.56

Exploring the underlying ideals of equality

As evident from the above discussion, beneath many of the questions regarding how to interpret formal and substantive equality guarantees in respect of critical health-related policy dilemmas lie contested theories of justice and power. In this section, I explore three questions that get played out in political and ethical theory: How much priority should we give to the worst off? What kind of equality is normatively desirable? And how do we measure who is worst off? These questions are critical if we are interested in incorporating human rights frameworks into health and development policymaking in concrete ways.

Equity, equality, and aggregate advances: Looking at the Millennium Development Goals

In a human rights framework, concern for equality implies that policies and programs affecting health — which go far beyond health care — must be evaluated with respect to their effects on disparities as well as their effects on aggregate advances.57 Both the ESC Rights Committee and Paul Hunt, the former Special Rapporteur on the right to health, have noted that human rights requires that routinely collected data be disaggregated along lines of gender, race, ethnicity, and even income quintile. Moreover, a variety of human rights documents call for special consideration for marginalized and disadvantaged groups.58

Therefore, it is clear that, from a human rights perspective, measuring progress in achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which today drive international development practice, in terms of overall societal averages is clearly insufficient. We must determine whether socially disadvantaged groups are faring better or worse.59 However, despite the fact that equality is, as a general rule, better for our health, and that more social equality appears to facilitate economic growth in the long run, there can be deep tensions between health maximization strategies and those focused on equality and distributive effects.

The MDGs set out eight goals with accompanying numerical targets and provide 60 indicators to measure progress.60 While some of the goals incorporate consideration for social circumstances because they are aimed at eliminating poverty, the three MDGs that explicitly address health goals do not do so expressly.61 Reduction of maternal mortality by 75%, for example (MDG 5), can in some cases be accomplished entirely by directing efforts toward the population areas with the largest aggregate numbers. Take for example a middle-income country, such as Mexico or Colombia, where the great preponderance of maternal deaths are concentrated in urban and peri-urban areas among the working poor, but in which inhabitants of remote rural areas have far higher maternal mortality ratios. These poor campesina women, who are often indigenous in states such as Chiapas or Chocó, face multiple dimensions of exclusion — based on language, gender, ethnicity, race, and class. In addition to poor access to health care, they often also have poor access to education, adequate water and sanitation, employment, and land rights.

On their own, there is nothing in the formulation of the MDGs to require that strategies to accelerate maternal mortality reductions be based upon anything but aggregate maximization, that is, best outcomes.62 In contrast, under a human rights framework we would be concerned with redressing the historic and ongoing patterns of discrimination these communities face, reflected by their relative maternal mortality ratios, among other things.

Substantive equality would seem to demand that even if social determinants cannot be equalized quickly, the campesina women at least should have equal access to family planning, skilled birth attendance, emergency obstetric are, and referral networks, which have been shown to be the pillars of an effective strategy to reduce maternal mortality.63 This is not a one-to-one equality regarding resources; providing these women in remote areas with anywhere near an equal claim to care as urban women will require not the same but far greater resources per person, simply because factors such as infrastructure, transportation, and communications staffing need to be ramped up. And, if budgets remain fixed, the result will almost certainly be that progress on achieving the aggregate goal will not be accomplished as fast. That is, more women will die, at least in the short and medium term. Unlike Ferraz, I tend not to accept that budgets need to remain fixed; indeed, insisting upon better treatment for the worst off may well be an effective means of increasing overall budgets, as enfranchised, urban middle classes are unlikely to accept reductions in their care.64 On the other hand, as a normative matter, the value of equality from a human rights perspective does not lie in its utility for achieving overall health goals.

It is worth noting that these dilemmas are not unique to health or social rights generally; we need only substitute access to justice for access to care to see that achieving substantive equality with respect to civil and political rights is equally complex. A government strategy that seeks to increase access to justice for the greatest number of people by building courthouses and funding public defenders’ and judges’ positions in urban areas — where more absolute numbers require such access — would never pass muster from a human rights perspective. The provision of meaningfully equal access to justice for people in poor, remote communities also requires infrastructure, translation services, and so forth; in practice it is not a matter of one-to-one equality of investment.65 If the human rights community has generally avoided delving into the programmatic and budgetary implications of demands to ensure equal access to civil and political rights, it cannot do so with respect to economic and social rights, such as health.

With respect to MDG 5, the ESC Rights Committee’s General Comment 14 calls for a basic obligation to ensure an “equitable distribution of health facilities, goods, and services.”66 What might such an equitable distribution require? The concepts of reasonableness, proportionality, and fairness are far better established in human rights law, but these concepts are quite alien to economists and development practitioners. The drafting of General Comment 14 went beyond the general common law notion of equity to import this concept from the health and development domains. But equity is not a uniformly defined concept in those realms either.

In his article in this issue, Ferraz tries to bridge the gap between the two discourses. Citing Amartya Sen, Ferraz notes that not all health inequalities constitute health inequities. It makes sense from a human rights perspective that to determine which inequalities constitute inequities, we need to examine how they are produced and, in turn, whether governments and other actors can be held accountable for redress. For example, greater investment should not be placed in men’s as opposed to women’s health in developed countries merely because women have longer life expectancies. Ferraz notes, too, that Dahlgren and Whitehead’s famous argument that “health inequalities count as inequities when they are avoidable, unnecessary and unfair” does not get us terribly far, because there is no consensus as to what is avoidable, unnecessary, and unfair.67

An equitable distribution of health facilities, goods, and services that could address maternal mortality, among other things, surely calls for more than merely establishing a threshold minimum if resources are available, which is another concept in human rights law.68 But how much more? According to the World Bank, equity might require providing some insurance for everyone through, for example, risk pooling in Colombia’s managed care scheme, health cards in Indonesia and Vietnam, and Thailand’s “30-baht” universal coverage scheme.69 By contrast, under the South African Constitution, “equity” requires that federal revenues be allocated to the provinces in accordance with a number of factors including disparate development levels.

Some have suggested that at a minimum equity requires addressing substantively unequal situations equally, that is, converting equality into a matter of process rather than outcome. Thus, if we could actually measure maternal mortality ratios (MMRs) effectively from year to year (which we cannot), equity would require that MMRs fall at equal rates. That is, an “equitable distribution of health facilities goods and services” might be that distribution which is necessary to reduce the MMR in a rural province with a high indigenous population in the same proportion as the reduction in the capital city, which for example might mean falling from 600 to 400 per 100,000 live births while the MMR in the capital fell from 75 to 50. In many countries, this would be a huge advance, but it would not approximate substantive equality in access to all the dimensions of a health system necessary uphold the right to be free of avoidable maternal death.

In short, if human rights frameworks are to be meaningfully integrated into development practice, in the MDGs and beyond, we must grapple with tensions between equality claims and aggregate advances. In turn, we will need to articulate the dimensions of equality that are important from a human rights perspective, and how they relate to concepts of equity in development and health policymaking.

What kind of equality should we seek from a human rights perspective? Equality measures and aspects

Human rights advocacy reports frequently combine distinct measures of inequality. Different kinds of statistics can be used to convey just how bad the situation is: for example, a comparison to the average, a comparison between the best and worst off in a society, or a comparison between the worst off and everyone else. Less often do we go the next step to examine what notion of inequality we are concerned with from a human rights perspective on health — and why.

Economists have developed a series of different kinds of rankings of inequality, including relative mean deviation, variance, coefficient of variation, standard deviation of logarithms, and GINI coefficients. Each of these reflects different intuitions about what matters in terms of (in)equality and how they relate to inequity.70 As Sudhir Anand and colleagues have suggested, the choice of inequality measures used in assessing health inequities depends on multiple considerations, including health domains and the weights attached to those domains.71 The choice is also a profoundly political and ideological one, as measures can to a greater or lesser extent reveal connections between national and international policies and varying impacts on different social groups.

The GINI coefficient, which is perhaps the most common measure of income inequality used in both development and in research regarding whether and how income inequalities affect health, contrasts actual income and property distribution with perfectly equal distribution. The value of the coefficient varies from zero (complete equality) to one (complete inequality).72 In a recent meta-analysis of how inequality affects health, other measures of income inequality were converted into GINI coefficients.73 The results of this study suggested “the existenceof a threshold of income inequality beyond which adverse impactson health begin to emerge” within countries (GINI 0.3 in this study). The authors suggested that the impacts of increased inequality were due not just to the fact that a relatively larger portion of the population lives in poverty but also to “spillover effects” that affect the health of the better off in society as well. As the authors of this study pointed out, “even a ‘modest’ association can amount to a considerable populationburden,” in this case excess risks of 3% in Japan, 11% inthe US, and 38% in Mexico compared with the countries havingGINI coefficients lower than 0.3.74

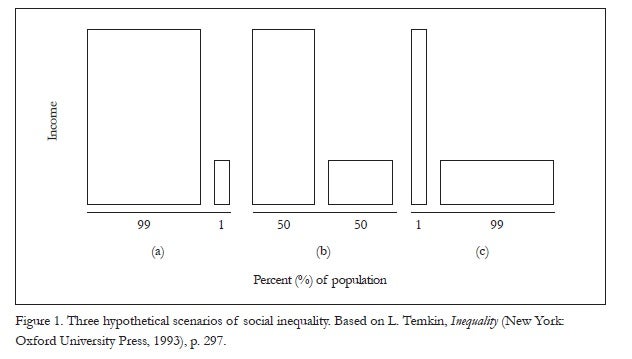

Although compelling, the mounting evidence of the empirical effects of social inequality from public health does not by itself capture what is essential to a normative human rights perspective.75 To get at what I mean, consider Figure 1, a variant of which philosopher Larry Temkin offers in his book, Inequality. We might understand the vertical axis of the diagram to represent income and the horizontal axis to represent percentages of a population. Temkin poses the question: Does the sequence get better or worse when read from left to right?76

Temkin argues that how we read the sequence depends upon the aspects of equality that concern us.77 For example, invidious discrimination against a small group is particularly offensive to a human rights perspective.78 Thus, in (a), if the 1% is being singled out on the basis of gender, race, caste, social group, or the like it would be extremely relevant for adjudging the overall justness of a societal distribution of resources as well as the distribution of health and well-being.

Another aspect or principle of equality is captured by the “maximin principle” of justice, first delineated by the liberal philosopher John Rawls. This principle asserts, in a general way, that a society’s institutional arrangement is just insofar as it improves the lot of the worst-off group, even if effecting a small improvement in the lot of the worst off means that the lot of the best off must be improved substantially more. That is, Rawls argues, inequalities may grow and still be consistent with a just ordering of society.79 Nevertheless, Temkin asserts that another aspect of equality is captured by a “maximin principle of equality,” which invests priority in reducing the gaps between the worst off and the rest of the population. This too seems to be fundamental to a human rights framework concerned with the most vulnerable. Here, the sequence seems to be progressively improving, because the worst-off group is faring better and better with respect to the number of people who are better off than the worst off are, and with respect to the average.80 Yet aggregate income and undoubtedly well-being is substantially diminished.

A third principle of equality that Temkin considers is the “additive principle of equality” which, along utilitarian lines, determines that the better situation between two competing options is the one in which there are the most individual instances of well-being and utility, for example, in comparison with individual instances of misery or disutility.81 A human rights framework concerned with general human flourishing would also need to consider this additive principle of equality, whereby the sequence is clearly worsening.

My point is that there are contested understandings of what justice requires in terms of equality, and human rights law does not adopt any single understanding in its entirety. Moreover, equality cannot be the only value in adjudging the justness of a society in a human rights framework. Temkin’s graphic is useful in illustrating that simplistic divisions between the haves and have-nots are rarely useful in making policy prescriptions. It is also useful in raising the possibility that in achieving greater equality — at the societal or global level — it is perfectly conceivable that we must first increase some aspects of inequalities as percentages of the population move through the sequence in either direction, as might happen for example if the middle class obtained access to courts to seek redress for health rights before the poor.82

How we look at Temkin’s figure, and at equality more generally in a human rights framework, must depend upon historical and social context. As noted above, it matters from a rights perspective if the worst-off people in society are worst off because they face deeply entrenched patterns of discrimination or stigma; it matters in what Figure 1 depicts as (b) and (c) as well as in (a). That is, in (b), half the population might belong to an ethnic group that is systematically favored over a different ethnic group; in (c), the distribution of resources might reflect a functional apartheid-like situation of extreme discrimination by a tiny minority against the vast majority.

Finally, it also matters whether we are considering a poor society or an affluent one. That is, it would seem that the worst off in a poor country such as Sierra Leone are relatively much worse off in comparison with the best off in that country — and in comparison with others in the world — than the worst off in a rich country such as the United States. What is at stake in terms of enjoyment of basic rights (or capabilities) of the worst off is far more urgent in such settings, as Amartya Sen has suggested.83 On the other hand, Anthony B. Atkinson has argued that as the general level of income rises, we should be more concerned about inequality because a rich economy can better afford to implement policies that promote equality.84 In short, our normative understanding of inequality from a human rights perspective cannot focus simply on absolute gaps but rather must look at relative positions and how they were produced in a given context over time, including the international context. In turn, applying a human rights framework to equality or equity must go beyond the quantitative rankings and measures set forth by the World Bank and others.85

When is one situation worse than another? Domains of equality and processes of public health priority setting

A further complexity in adjudging equality demands in health lies in the fact that it is not at all clear how to determine who is worst off. While Rawls’ theory of justice as fairness was undoubtedly the single most influential theory of distributive justice in the 20th century, Kenneth Arrow and others pointed out that as Rawls assumed for the sake of building his theory that everyone was in good health, it was impossible to ascertain from his original theory whether a poor person in good health should be considered better off than a slightly economically better-off person who is ill.86

Amartya Sen has argued that income and even Rawls’ concept of primary goods (education, employment, and the like) are not the right spaces in which to measure social inequalities. Rather than focusing on the means of living, Sen suggests, we should focus on the actual opportunities for living, doing, and being. He has proposed that we should measure inequalities in terms of capabilities — “the ability to achieve various combinations of functionings that we can compare and judge against each other.”87 Thus, for example, a disabled person with the same income as a non-disabled person does not enjoy the same capabilities because he or she suffers from a “conversion handicap,” a differential ability to convert resources into actual opportunities to enjoy good living — and to effectively enjoy rights.88

As Sen’s argument implies, relative differences in income can translate into absolute differences in capabilities, or effective enjoyment of rights, including the right to health. That is, it is not so much what you have but what you can do with what you have. Capabilities are influenced by individual states of health and disability, but they are also heavily influenced by the nature of society. Thus, pro-poor policies are not enough to address human rights concerns regarding inequalities. Sen’s, as well as Burns’s arguments in this issue, support the point that urgent transformation of social conditions is required to reduce not only the incidence of mental disability but also the penalty.89

Capability theory is also important for a rights framework as it contrasts with the utilitarian forms of priority setting that prevail in public health. For example, rights-based slogans relating to health care reform in the United States call for “equity” — in this case meaning equal access to care according to need rather than ability to pay. As straightforward as that seems in terms of human rights principles, most explicit public health priority setting is done through cost utility measures that attempt to treat people equally not according to their need, but according to their capacity to benefit.

For example, cost utility analysis might compare the cost of treatment A with treatment B, where treatment is needed to generate one additional “quality-adjusted year of life” (QALY). To calculate the QALYs of an intervention, each year in perfect health is assigned the value of 1.0, down to a value of 0.0 for death. Years that would not be lived in full health, due to some disability or impaired functioning, are assigned a value between 0 and 1. QALYs are used at all levels — from hospitals and health maintenance organizations to national health systems.90

The problem with QALYs and their counterpart in international health programming — Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) — is that they do not take into account rights concerns. For example, a blind application of QALYs would lead us to conclude that there is no value in saving a 69-year-old if life expectancy is 65. QALYs place no priority on the worst off — either in terms of social circumstances or severity of health conditions. Although they are unquestionably useful, QALYs and DALYs will always favor treatment for relatively minor conditions that in aggregation sum up to lots of QALYs; conversely, they will always disfavor treating people who suffer from costly conditions that are not susceptible to full- or near-full recovery.91

A single quantitative scale for comparing health capabilities and the inequalities in them is incompatible with a deontological rights framework that requires people be treated as ends and not means, just as it is incompatible with capabilities theory. As Jennifer Prah Ruger has noted, “one cannot quantifiably compare one individual’s inability to hear or see with another’s inability to bear children or to walk. These reductions in individuals’ capabilities for functioning are qualitatively different and different people will have widely diverging views on which functional capability reduction is better or worse than the other.”92

Finally, in a rights framework, it matters who is assessing the relative loss of function — the patient with the condition, the society, or merely the paying public in an insurance system. As Burns eloquently explicates, human rights principles demand voice accountability to those affected by a specific condition, including mental disabilities of all kinds. On the other hand, given certain conditions and/or experiences of disempowerment, some people may not perceive their disability or impairment to be as great as it really is. A credible rights theory requires some objective account of how both biological and social conditions impede certain people from being and doing — that is, from effectively enjoying their rights to health, as well as other rights.93

If health and health inequalities are necessarily multidimensional concepts in a human rights framework, we require a process for arriving at priority setting in health that does not depend solely upon cost utility measures. The Rawlsian theorist Norman Daniels, Sen and his followers, and others all suggest the need for a process that allows for “reasoned public-policy decision-making in the face of multiple, and even conflicting, views on health.”94 All of these theories — whether based on Rawls, Sen, or Jurgen Habermas — invest importance in the process of deliberation, in the notion that public deliberation and the continued scrutiny of public values it entails can shape how we assess justice — and the need for equality — in health and other spheres.95 In a rights framework, processes for determining which inequalities are truly inequities require not just “relevant grounds” for decision making, “partial rankings,” or “incompletely theorized agreements”; they also crucially demand meaningful participation.

As I explored in the most recent issue of this journal, however, empowering participation depends to a great extent upon the context in which it occurs and what is up for contention.96 Nancy Frazer has noted that effective participation requires “the sort of rough equality that is inconsistent with systemically-generated relations of dominance and subordination.”97 In “stratified societies” — societies whose basic institutional framework generates unequal social groups in structural relations of dominance and subordination — “full parity of participation in public debate and deliberation is not within the reach of possibility.”98 Thus, we should be cautious about expectations for health and health care equity emerging from priority-setting processes that occur against the backdrop of gross social inequality. As Frazer has argued, “any consensus that purports to represent the common good in this social context should be regarded with suspicion, since this consensus will have been reached through deliberative processes tainted by the effects of dominance and subordination.”99

In short, equality is a multi-faceted and complex, contextually bound concept, and how we weigh equality and make allocations in health literally will determine who lives and who dies. In order to argue for how much priority should go to the worst off in society — as well as to how to discern who is worst off regarding health conditions — we require deliberative, participatory processes and cannot rely solely on standardized quantitative measures in a rights framework. Nevertheless, in order for those processes to be meaningful, we require some degree of background equality. Thus, to the empirical public health evidence on the detrimental effects of social inequalities, we can add the normative argument that steep social inequalities undermine the possibility of establishing just institutional arrangements and priorities that would protect the equal and effective enjoyment of health and other rights.

Concluding reflections

The great power of applying a human rights framework to health lies in denaturalizing the inequalities that pervade our societies and our world, whether based on gender, caste, race, or some other characteristic. In this article, I have argued that a human rights framework concerns itself with ensuring that every person, by virtue of being human, enjoys a full set of rights. It also concerns itself with defining the content of those rights, including health, to which people with different biological and social needs are entitled, and the scope of ensuing governmental obligations. Inequalities — and discrimination — affect all of our myriad forms of identity, but I have emphasized here the importance of addressing social inequalities to promote the effective enjoyment of rights to health and the social determinants of health.

In a human rights framework, health is a reflection of power relations as much as biological or behavioral factors. The gross social inequalities — pathologies of power, to use Paul Farmer’s term — that ravage so many countries around the world today not only create patterns of ill health and disability. They also limit the ability of people to participate fully in their societies, and to hold their governments and other actors accountable.

In thinking through how to address situations of stark inequality, a focus on the poor — the worst off in terms of income — seems an obvious step because they generally have the worst health problems and because human rights calls for a special concern for the marginalized and disadvantaged. However, as we have seen, the picture is decidedly more complex. At the same time as we attempt to ensure that policies and programs more effectively promote the rights of the worst off (defined more broadly than merely in terms of income) we also need to take action to reduce inequalities across the whole of society, as well as across the international order, a focus topic for the next issue of Health and Human Rights. One key step is to treat health systems as the core social institutions that they are, and to ensure that financing and priority-setting processes within them facilitate greater substantive equality and inclusion.100

Human rights law does not magically resolve debates within the public health and development fields as to which health inequalities are necessarily inequities. However, a human rights framework does establish that all people, by virtue of being human, have a claim for redress when they are treated unfairly and have a right to participate in determining what equity and equality require in a given context. As Thomas Pogge has suggested, the poor and disadvantaged can thus no longer be seen merely as “shrunken wretches begging for our help” but must be addressed as “persons with dignity who are claiming what is theirs by right.”101

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to colleagues at the Harvard Human Rights Program and in particular to Aeyal Gross, whose thinking on these issues has been immensely useful. I am also, as ever, deeply appreciative of Adriana Benedict’s assistance with the technical preparation of this article.

Alicia Ely Yamin, JD, MPH, is the Joseph H. Flom Global Health and Human Rights Fellow at Harvard Law School and an Adjunct Lecturer at the Harvard School of Public Health. She also serves as a Special Advisor to Amnesty International’s global campaign on poverty, Demand Dignity.

Please address correspondence to the author at ayamin@law.harvard.edu.

References

1. Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), G.A. Res. 217A (III) (1948), preamble. Available at http://www.un.org/Overview/rights.html.

2. WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health (Geneva: WHO, 2008); see also, M. Powers and R. Faden, Social justice: The moral foundations of public health and policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006); S. Anand, F. Peter, and A. Sen (eds), Public health, ethics and equity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004).

3. “An interview with Sir Michael Marmot,” Social Medicine 4/2 (2009), pp. 109–112.

4. World Bank, World Development Indicators, cited in Table 8 in R. Mohan “The Growth Record of the Indian Economy, 1950–2008: A Story of Sustained Savings and Investment” (Keynote Address at the Growth and Macroeconomic Issues and Challenges in India conference organized by the Institute of Economic Growth, New Delhi, India, February 14, 2008). Available at http://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Speeches/PDFs/83118.pdf.

5. For a recent report on malnutrition rates in India by ActionAid, see http://www.actionaidindia.org/index.htm; see also, R. Mohan, “The growth record of the Indian economy, 1950–2008: A story of sustained savings and investment,” (keynote address at the Growth and Macroeconomic Issues and Challenges in India conference organized by the Institute of Economic Growth, New Delhi, India, February 14, 2008). Available at http://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Speeches/PDFs/83118.pdf.

6. “World food day… No food for India,” India Info.com (October 16, 2009). Available at http://news.indiainfo.com/article/091016103843_world_food_day/475016.html.

7. See B. Milanovic, “World income inequality in the second half of the 20th century,” World Bank Research Paper (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2001), p. 78, cited in A. de Vita, “Inequality and poverty in global perspective,” in T. Pogge (ed), Freedom from poverty as a human right (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 103–132, at 104.

8. As the Center for Economic and Social Rights recently stated, because of the global economic downturn, 400,000 additional infants are predictedto die each year in the short-term and “the right to education — particularly that of girls — is threatened as families can no longer afford the direct andindirect costs of sending their children to school, requiringthem instead to carry out domestic or paid work.” And literacy — especially girls’ literacy — is closely linked to a set of better health outcomes. See “Global crisis hits most vulnerable,” UNESCO (March 3, 2009). Available at http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=44687&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html; International Labour Organization (ILO), A global policy package to address the global crisis (Geneva: International Labour Office, 2008). Available at http://www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/inst/download/policy.pdf. Cited in I. Saiz, “Rights in a recession? Challenges for economic and social rights enforcement in times of crisis,” Journal of Human Rights Practice 1/1 (2009), pp. 277–293.

9. See, for example, WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (see note 2); I. Kawachi and B. Kennedy, The health of nations: Why inequality is harmful to your health (New York: The New Press, 2002).

10. See, for example, R. Wilkinson and K. Pickett, The spirit level: Why more equal societies almost always do better (London: Penguin, 2009).

11. “An interview with Sir Michael Marmot” (see note 3); WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (see note 2).

12. I consider effective enjoyment of rights to be closely related to Amartya Sen’s notion of capabilities. See, for example, A. Sen, Inequality reexamined (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992); see also, A. Sen, Commodities and capabilities (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

13. See, for example, World Health Organization, Human rights, health and poverty reduction strategies, WHO/ETH/HDP/05.1 Draft (Geneva: WHO, 2005). Available at http://www.who.int/hhr/news/HRHPRS.pdf.

14. See, for example, I. Khan, The unheard truth (New York: Norton, 2009). Available at http://shop.amnesty.org/products/the-unheard-truth-a-book-by-irene-khan; T. Pogge (ed), Freedom from poverty as a human right: Who owes what to the very poor? (New York: Oxford University Press and UNESCO, 2007).

15. See Universal Declaration of Human Rights (see note 1).

16. Given the vast literature of social justice and health, it is notable how few scholars have engaged with the framework of human rights. The few articles that have attempted to bridge the gap have related poverty, equity, and human rights, rather than exploring the demands of the complex notion of equality. See, for example, P. Braveman and S. Gruskin, “Poverty, equity, human rights and health,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 81/7 (2003a), pp. 539–545; P. Braveman and S. Gruskin, “Defining equity in health,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 57 (2003b), pp. 254–258.

17. A. Sen, “Elements of a theory of human rights,” Philosophy and Public Affairs 32 (2004): 315–356.

18. “Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in healthcare is the most shocking and inhumane.” Martin Luther King Jr. (National Convention of the Medical Committee for Human Rights, Chicago, 1966).

19. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI) (1966), Art. 2. Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/cescr.htm.

20. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 20, Non-Discrimination in Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, UN Doc. No. E/C.12/GC/20 (2009), para. 7.

21. Ibid., para. 10.

22. According to the UNAIDS Protocol for the identification of discrimination against people living with HIV, such discrimination includes “any measure entailing an arbitrary distinction among persons depending upon their confirmed or suspected HIV serostatus or state of health.” UNAIDS, Protocol for the identification of discrimination against people living with HIV (Geneva: Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2000). Available at http://data.unaids.org/Publications/IRC-pub01/JC295-Protocol_en.pdf.

23. The UNAIDS/OHCHR International guidelines on HIV/AIDS and human rights call for broad anti-discrimination laws and policies, not just with respect to health care but also to social security, welfare benefits, employment, education, sport, accommodations, clubs, trade unions, qualifying bodies, access to transport, and other services. UNAIDS, 2008 Report on the global AIDS epidemic (Mexico City: Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS), p. 77. Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/2008/2008_Global_report.asp.

24. L. Temkin, Inequality (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 101.

25. C. MacKinnon, Sex equality (New York: Foundation Press, 2001).

26 P. Braveman, “Measuring health inequalities: The politics of the World Health Report 2000,” in R. Hofrichter (ed), Politics, ideology and inequity and the distribution of disease (San Francisco, CA; John Wiley and Sons, 2003), pp. 305–320.

27. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, UN Doc. No. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000), para. 20.

28. See, for example, Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, General Recommendation No. 32, The meaning and scope of special measures in the

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms Racial Discrimination, UN Doc. No. CERD/C/GC/32 (2009). Available at http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/type,GENERAL,CERD,,4adc30382,0.html; see also, International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, G.A. Res. 2106A (XX) (1965), para. 2(2). Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/ratification/2.htm.

29. The recent Stupak-Pitts amendment to the US House of Representatives Health Care Reform Bill would make it even more difficult for women in families earning up to $88,000 a year to obtain an abortion. Stupak of Michigan Amendment to H.R. 3962, as reported by the House Committee on Rules, November 6, 2009.

30. CESCR General Comment No. 14 (see note 27), para. 12.

31. This “disproportionate burden” concept has been fleshed out somewhat more by different courts. The Colombian Constitutional Court found, for example, that such a burden would be “unbearable” if it affected a person’s “subsistence minimum.” Constitutional Court of Colombia, Sala Segunda de Revisión, Judgment T–760, Magistrado Ponente: Manuel José Cepeda (2008), para. 4.4.5.3.

32. The House of Representatives Bill passed on November 7, 2009, allows older people to be charged as much as twice the premiums of younger people. US House of Representatives 111th Congress, 1st Session, America’s Health Future Act (2009).

33. CESCR General Comment No. 14 (see note 27), para. 29.

34. A. Sen, “Elements of a theory of human rights,” Philosophy and Public Affairs 32 (2004), pp. 315–356.

35. A. Williams, “Inequalities in health and intergenerational equity,” Health Economics 6 (1997), pp. 117–132.

36. See G. Persad, A. Wertheimer, and E. Emmanuel, “Principles for allocation of scarce medical interventions,” Lancet 373/9661 (2009), pp. 423–431.

37. Broadening from specific interventions to resources, Norman Daniels suggests the “prudential lifespan account,” which assumes we all age and that resources should be allocated as if we all go through different life stages. See N. Daniels, Just health: Meeting health needs fairly (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008), p. 178.

38. CESCR General Comment No. 20 (see note 20), para. 8.

39. Constitutional Court of Colombia, Judgment C–521, Magistrado Ponente: Clara Inés Vargas Hernández (2007).

40. For example, customary and statutory laws around the world that prohibit women from inheriting property have enormous impacts on their well-being, as well as their agency and dignity.

41. Uganda Penal Code Act, revised, para. 145 (1950).

42. Naz Foundation v. Government of NCT of Delhi and Others, Delhi High Court, India (2001), WP(C) No. 7455/2001.

43. Ferraz makes a separate argument about the judicial decisions producing more inequality in Brazil as well.

44. Constitutional Court of Colombia, Judgment T–654, Magistrado Rodrigo Uprimny (2004), concurrence.

45. CESCR General Comment No. 20 (see note 20), para. 8.

46. International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, G.A. Res. 34/180, Art. 10(2) (1979). Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/cedaw.htm.

47. CERD General Recommendation 32 (see note 28), para. 8: “To treat in an equal manner persons or groups whose situations are objectively different will constitute discrimination in effect, as will the unequal treatment of persons whose situations are objectively the same.”

48. CESCR General Comment No. 20 (see note 20), para. 8.

49. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, G.A. Res, 61/106, Art. 2 (2006). Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/ratification/15.htm.

50. Eldridge v. British Colombia (Attorney General) (1997), 3 SCR 624.

51. See A. Gross, “The right to health in an era of privatization and globalization: National and international perspectives,” in D. Barak-Erez and A. Gross (eds), Implementing social rights (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2007), pp. 289–339, at 310.

52. The case was decided on the basis of the right to life and security, not a right to health per se. Chaoulli v. Quebec (Attorney General) (2005) 1 SCR 791.

53. Gross (see note 51), p. 312; see also, dissent in Chaoulli (see note 52), para. 164.

54. Persad et al. (see note 36).

55. See judgments SU–225 de 1998 (M. P. Eduardo Cifuentes Muñoz) and SU–819 de 1999 (M. P. Alvaro Tafúr Galvis) por H. Torres Corredor, “La Corte Constitucional entre la economía y el derecho,” in Pensamiento Jurídico, No. 15 (Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2002).

56. See J. P. Ruger, “Health and social justice,” Lancet 364/9439 (2004), pp. 1075–1080.

57. Paula Braveman and Sofia Gruskin (2003a, see note 16) have stated, for example, that “routine assessment of potential health implications for different social groups should become standard practice in the design, implementation and evaluation of all development policies.” Available at http://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0042-96862003000700013.

58. Human rights, health and poverty reduction strategies (see note 13).

59. Ibid.

60. The goals are as follows: eradicate extreme poverty and hunger; achieve universal primary education; promote gender equality and empower women; reduce child mortality; improve maternal health; combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases; ensure environmental sustainability; and develop a global partnership for development. UNDP, “About the MDGs: Basics.” Available at http://www.undp.org/mdg/basics.shtml.

61. Goals 4, 5, and 6 address child mortality; maternal health; and HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases, respectively.

62. See D. Gwatkin, Who would gain most from efforts to reach the Millennium Development Goals for health: An inquiry into the possibility of progress that fails to reach the poor (Washington, DC: The World Bank, December 2002).

63. L. P. Freedman, W. J. Graham, E. Brazier, et al., “Practical lessons from global safe motherhood initiatives: Time for a new focus on implementation,” Lancet 370/9595 (2007), pp. 1383–1391.

64. See the argument for this approach by the director of Human Rights Watch, Kenneth Roth, in his article “Defending economic, social and cultural rights: Practical issues faced by an international human rights organization,” Human Rights Quarterly 26/1 (2004), pp. 63–73.

65. Ibid.

66. CESCR General Comment No. 14 (see note 27), para. 43.

67. G. Dahlgren and M. Whitehead, Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Background document to WHO — strategy paper for Europe (Stockholm: Institute of Future Studies, 1991). Available at http://www.framtidsstudier.se/filebank/files/20080109$110739$fil$mZ8UVQv2wQFShMRF6cuT.pdf.

68. The concept of equity is supplemented by the concept of a minimum level under human rights law. That is, there should be at least a minimum level of obstetric services. UN process indicators provide content to this idea. See A. E. Yamin and D. P. Maine, “Maternal mortality as a human rights issue under international law,” Human Rights Quarterly 21/3 (1999), pp. 563–607.

69. World Bank, World Development Report 2006, Washington DC, available at http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWDR2006/Resources/477383-1127230817535/082136412X.pdf.

70. For definitions, see R. M. Sundrum, Income distribution in less developed countries (New York: Routledge, 1990); see also, A. Sen and E. Foster, On economic inequality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

71. S. Anand, F. Diderichsen, T. Evans, et al., “Measuring disparities in health: Methods and indicators,” in T. Evans, M. Whitehead, F. Diderichsen, et al. (eds), Challenging inequities in health: From ethics to action (London: Oxford University Press, 2001).

72. Amartya Sen, who is critical of the GINI coefficient, proposes an “intersection approach” that discerns whether and when a number of different measures agree versus when they produce different outcomes. Sen and Foster (see note 70), p. 33.

73. N. Kondo, G. Sembajwe, I. Kawachi, et al., “Income inequality, mortality, and self rated health: Meta-analysis of multilevel studies,” British Medical Journal 339/102 (2009), pp. 1–9 [online edition]. Available at http://www.bmj.com/cgi/reprint/339/nov10_2/b4471.

74. Ibid.

75. Wilkinson and Pickett (see note 10).

76. Temkin (see note 24), p. 297.

77. Ultimately, Temkin argues that it gets first worse and then better.

78. Temkin (see note 24), p. 30.

79. J. Rawls, A theory of justice (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971).

80. Temkin (see note 24), p. 34.

81. Ibid., p. 41.

82. Ibid., pp. 104–105

83. Sen and Foster (see note 70), p. 36.

84. A. B. Atkinson, “On the measurement of inequality,” Journal of Economic Theory 2 (1970), p. 251, cited in Temkin (see note 24), p. 183.

85. World Bank (see note 69).

86. See, for example, K. Arrow, “Extended sympathy and the possibility of social choice,” Equality and Justice in a Democratic Society 7/2 (1978), pp. 223–237.

87. A. Sen, The idea of justice (Cambridge: Harvard University Press/Belknap Press, 2009), p. 233.

88. Ibid., p. 258.

89. Ibid., p. 259.

90. See National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), “Measuring effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.” Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/newsroom/features/measuringeffectivenessandcosteffectivenesstheqaly.jsp.

91. In ethics these are known as the aggregation and severity problems.

92. Ruger (see note 56).

93. Ibid.

94. Ibid. See also, Daniels (see note 37).

95. Sen (see note 87), p. 242.

96. See A. E. Yamin, “Suffering and powerlessness: The significance of promoting participation in rights-based approaches to health,” Health and Human Rights: An International Journal 11/1 (2009), pp. 5–22. Available at http://www.hhrjournal.org/index.php/hhr/article/view/127/200.

97. N. Fraser, “Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy,” Social Text 25/26 (1990), pp. 56–80, at 76.

98. Ibid.

99. Ibid., p. 73.

100. See P. Hunt and G. Bachman, “Health systems and the right to the highest attainable standard of health,” Health and Human Rights: An International Journal 10/1 (2008), pp. 81–92. Available at http://www.hhrjournal.org/index.php/hhr/article/view/22/69.

101. Pogge (see note 7), p. 4.