Volume 22/2, December 2020, pp 167 – 176

Neiloy R. Sircar and Allan A. Maleche

Abstract

Kenya encourages HIV testing and notification services, especially for key and affected populations (KAP), in order to identify persons living with HIV and link them to treatment. Kenya and international supporters of its HIV program have sought to scale up these services through increased capacity and training. However, little is known about how the HIV strategy is implemented and sustained, particularly regarding human rights. Kenya aspires to support human rights in adherence to a human rights-based approach (HRBA) to HIV. This exploratory qualitative study assesses Kenya’s progress in implementing an HRBA to HIV. KAP participants conveyed mixed perspectives on their HIV care services, conveying distrust in Kenya’s public health care system while also recognizing improvement in some patient-provider interactions. Providers see the need to better engage KAP through community-based organizations and undergo improved, consistent training to sustain practices and policies that promote their rights realization. We believe that our study contributes to both HIV and human rights research by capturing successes and challenges in Kenya’s implementation of an HRBA to HIV. These findings should inform future collaboration between Kenyan health authorities and KAP, and shape HIV policies and practices to improve health care utilization and human rights realization.

Introduction

Human rights-based approaches (HRBA) are a field of study within legal and public health research. HRBA is a conceptual framework based on international human rights norms and laws and is, operationally, oriented to the protection, respect, promotion, and fulfillment of human rights that anchors public authorities (duty-bearers) to be accountable to individuals and communities (rights-holders) when developing, implementing, and evaluating programs and policies.[1] In practice, following an HRBA means integrating the principles of nondiscrimination, participation, empowerment, accountability, and linkages to other rights into the design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of health-related programs and interventions.[2]

Scholars identify rights-based approaches to health, deriving them from best practices and lessons learned, which informs policy development and contributes to advocacy for human rights and health.[3] Better understanding the “approach” in HRBA could bolster the monitoring and evaluation of a program, policy, or practice and support the construction of indicators for achieving rights realization in service to supporting health outcomes.[4] Operationalizability is important to avail HRBAs of the policy analysis capacities that many public health professionals are trained in and to provide legal analyses and respective tools to support accountability.[5]

HRBAs are significantly discussed within the context of HIV.[6] An investigation into whether and how a rights-based approach is adhered to, in a context where public health authorities embrace HRBAs and recognize the right to health, could yield rich outcomes describing the implementation successes and challenges that come with operationalizing an HRBA to HIV. Developing a practice for HRBAs would include measurable—and contextual—indicators both for achieving targets in HIV testing, treatment, and prevention and for comprehensively realizing human rights among people living with HIV and key populations at risk of acquiring HIV.[7]

Background

HIV and human rights in Kenya

Kenya recognized the human right to health in its 2010 Constitution.[8] The HIV and AIDS Prevention and Control Act (2006) enumerates the rights of people living with HIV that are inherent to realizing the right to health (including consent, confidentiality, and privacy).[9] In addition, Kenya is a signatory to numerous international human rights treaties whose committees (the authorities overseeing each treaty’s implementation and growth) have recognized the right to health, including for the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.[10] Kenya is also a member of the East African Community, which passed (and Kenya assented to) the HIV and AIDS Preventions and Management Act (2012).[11]

Kenya’s HIV epidemic remains substantial.[12] Kenya is one of the top five most-burdened countries globally in spite of successes in expanding HIV testing and connecting people living with HIV to treatment.[13] In Kenya, the burden of HIV falls disproportionately on “key and affected populations,” or KAP, a group of communities that includes gay men and other men who have sex with men (MSM), people who inject drugs (PWID), female sex workers (FSW), and young women aged 15 to 24. Approximately half of all people living with HIV in Kenya were unaware of their HIV status in 2018.[14] Testing rates among key populations and young women remain suboptimal: while 80–90% of FSW in Kenya report having tested for HIV within the past 12 months, only 77% of MSM, 84% of PWID, and about 50% of women aged 15–19 report having done so (though 80% of young women aged 20–24 reported testing).[15]

To address this health inequity, the Kenyan National AIDS and STI Control Programme, the Ministry of Health, other Kenyan public health authorities, and international supporters such as the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) have been scaling up their HIV testing strategies to increase testing rates and to widely implement assisted partner notification services in order to identify people living with HIV and connect them to treatment. (On January 1, 2020, PEPFAR issued guidance to its programs and partners calling for the suspension of partner notification services, citing concerns raised over confidentiality, consent, and respect for human rights, particularly among key and affected populations such as sex workers, MSM, and adolescent girls and young women. This guidance came after our study’s data collection had concluded.)[16]

Voluntary testing for HIV, and encouraging—without coercing—partner notification services, are cornerstones of the rights-based approach to HIV.[17] The National AIDS and STI Control Programme’s 2015 HIV Testing Services Guidelines detail several approaches to facilitate access to HIV services, testing, and treatment. Primary approaches involve facility- and community-based settings that offer both client- and provider-initiated testing and counseling.[18] Assisted partner notification services have been particularly effective in identifying persons for outreach and testing, utilizing an index case (a person living with HIV) to identify other parties to simplify case finding. Building several avenues to connect persons at risk for HIV, or living with HIV, is a public health priority.[19]

HIV and patients’ rights

Human rights concerns with HIV testing and notification services relate to how these strategies pursue their objectives to increase testing rates, with particular attention paid to communities already experiencing vulnerability with respect to their rights. KAP in Kenya and elsewhere have described their fears of coerced disclosure, erasure of privacy and confidentiality, heightened stigmatization and resulting discrimination, and violence (physical, emotional, and otherwise) from their partners, families, or communities.[20] Such fears are not based solely on perceptions; sex work is illegal in Kenya, as is homosexual behavior and drug use. Young women in Kenya and East Africa experience pervasive forms of coercion, which hinders their autonomy and rights realization.[21]

Fear of coercive approaches to encourage testing undermines both health objectives and individuals’ rights. In 2013, the nonconsensual disclosure of individuals’ HIV positive status in Kenya was strikingly commonplace, and coerced testing was also prevalent, affecting community perspectives on health services and HIV testing generally.[22] A 2016 qualitative study in Kenya found that individuals’ sex highly influenced how and when they disclosed their HIV status, with some women expressing fear of social and financial abandonment or violence if they disclosed their status.[23] A 2018 study echoed these findings, reporting that 13% of Kenyan women living with HIV were unlikely to disclose to their partners.[24]

Effective HRBAs to HIV training require a strong legal and policy framework for education and practice, and as of 2020 neither the National AIDS and STI Control Programme’s guidelines for partner notification services nor the required privacy regulations under the 2006 HIV and AIDS Prevention and Control Act were being implemented. The laws that exist in Kenya are meaningful only if the rights they protect are perceived as real and held by KAP—and if, where violations occur, the violators are held accountable swiftly and transparently.

Assessing Kenya’s HRBA to HIV

Our exploratory qualitative study examined how Kenyan health care professionals implement a rights-based approach to HIV testing and notification practices with respect to KAP. At the same time, we spoke with KAP individuals to better understand why they under-test relative to their risk, what they perceive as barriers and areas for reform, what concerns they have regarding disclosure, and how those concerns might be addressed.

The key research questions were as follows: (1) How is Kenya implementing an HRBA to HIV testing and assisted partner notification services?; (2) How are KAP experiencing these services?; and (3) Where can Kenya strengthen its HRBA to ensure KAP’s rights realization and utilization of HIV services? We posit that perspectives, attitudes, and opinions from rights-holding communities (KAP in our study) provide a measurable indicator for rights realization (the self-perceived enjoyment of rights and means to redress violations thereto) and, importantly, assessing how effectively a public health program or policy adheres to a rights-based approach. HRBA studies are infrequent in the public health literature, and studies on HRBA implementation even more so. Our study aimed to help bridge the gap between theoretical HRBAs and applied HRBAs within Kenya’s HIV and KAP context.

Limitations

Measuring the impact of HRBAs is challenging, particularly as perceptions of one’s rights realization may be subject to several intersectional determinants. Our hypothesis—that Kenyan KAP’s perceptions of their rights and Kenya’s HIV programs can function as one possible indicator—is novel but contributes to understanding the successful operationalization of HRBAs to HIV.

Methods

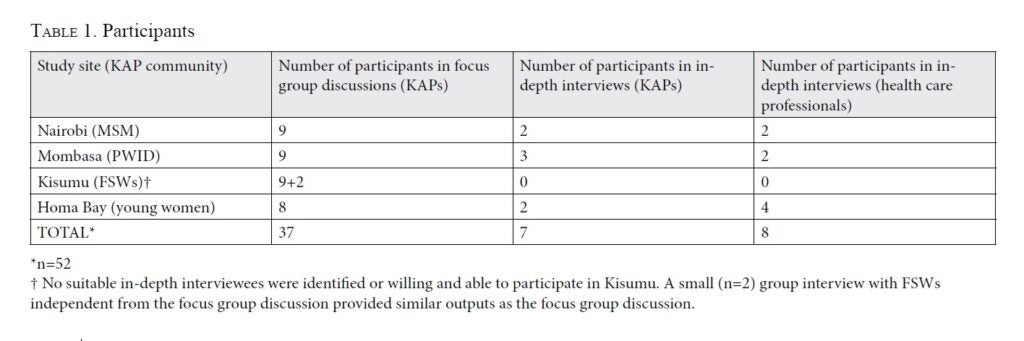

Our protocol and other methodology details have been published in another issue of this journal.[25] In brief, we worked with community-based organizations to establish four study sites across southern Kenya that represent significant population centers for the four KAP communities included: Nairobi (MSM), Mombasa (PWID), Kisumu (FSW), and Homa Bay (young women). Table 1 summarizes our engagement with participants. We also invited senior leadership from Kenya’s HIV programs to participate, and we informed pertinent county and national authorities of our study’s purpose and utility.

Kenyans familiar to these communities transcribed the interview recordings. Interviewers provided analytic memos following their transcription to ensure that our analysis was informed by and reflected participation from the communities. A Kenyan qualitative analyst provided memos for each study site’s outcomes; we (the authors) then conducted a legal analysis based on these memos and the original transcriptions.

We adopted a grounded theory approach for this study. However, we hypothesized that human rights realization as enabled through a rights-based approach to HIV testing will contribute to greater trust and confidence in the health care system and result in more persons at risk for HIV voluntarily testing and using notification services.

Results and discussion

Several participants reflected positively on their interactions with HIV care services; many felt that their situation had improved compared to earlier accounts from their own histories or the shared experiences within their groups. Nevertheless, our results indicated mixed sentiments among KAP with regard to government-affiliated health services. While we found only a few disagreements, the general consensus was that KAP are not utilizing services (including testing services) owing to a lack of trust, confidence, and continued stigmatization or anticipation of stigma.[26] We interpret KAP’s under-utilization of HIV testing and notification services as relating to under-implemented mechanisms for the protection, respect, promotion, and fulfillment of the rights to privacy, confidentiality, consent, and dignity.[27]

Men who have sex with men expressed distrust and anticipation of stigma from interactions with public health care providers.

Interviewees reported feeling objectified by health care providers and having their confidentiality and privacy breached through gossip. They also noted the comparative lack of KAP-friendly services in Kenya outside of Nairobi. Given that homosexual activity is illegal in Kenya, MSM participants were concerned about having any records that might be accessed and put them in future jeopardy. One MSM interviewee in Nairobi said:

You know government facilities, people know that they’re owned by government. [T]hey keep records, they keep reports, people will fear the government facility has to say how many gay men did you see? How many sex workers did you see? Do you know where they live? That fear of giving real information that they feel it may end up with the government.

Judgmental interactions also diminished MSM participants’ trust and confidence in their health care providers. For example, one health care worker told a patient that they needed to “change their sexuality” and “needed prayers to change [their] way of living.”

MSM participants did not want to lose control of their privacy and personal information, and they worried that disclosing their status might encourage violence against them. They shared the perception that testing is mandatory at government hospitals and clinics, which by itself might act as a barrier to testing.

People who inject drugs expressed concerns about interacting with government-affiliated authorities, stemming from histories of negative interactions and prejudice.

Participants felt stigmatized when interacting with public health care services, notably at the point-of-care level provided by nurses. One PWID interviewee said, “I cannot trust [them] because of the way they treat us, both nurses and doctors treat us as animals. They use so many harsh words on us that’s why we tend to avoid such places.” If community-based organizations and KAP-friendly services are not available, PWID health care-seeking is less likely or is delayed. At the same time, PWID were more accepting of partner notification services. They felt that once a person’s status is known, sharing that status with others in their community is proactive and supportive of others’ testing. Still, PWID felt that their rights are often precarious, particularly when interacting with police and government-affiliated services (that may expose them to police).

Female sex workers felt vulnerable to coercion and prejudice.

FSW participants in Kisumu harbored negative sentiments toward government facilities and nurses in particular. They expressed reservation in sharing information with health care providers out of concern for their confidentiality and privacy, noting that health care providers and workers tend to gossip, which can lead to disclosing patients’ personal information. Multiple interviewees felt that some providers coerce their community to test, and several felt that providers are judgmental and unlikely to respect privacy and confidentiality. While most FSW participants felt that partner notification services are beneficial, some also had concerns over how Kenya has encouraged partner notification in its HIV testing and treatment strategy. They felt particular pressure to provide contacts for partner notification services and to disclose one’s HIV status (or allow it to be disclosed) to third parties.

On the topic of confidentiality, one sex worker from Kisumu said:

Thirty minutes after testing positive, you will see four people—the person for PNS [partner notification service], another with a file, and allocator for treatment, including the adherence counselor crowding, so it is stressful. Even the guys who dish out food will get to know that somebody tested positive. No confidentiality because of the numbers that NGOs [nongovernmental organizations] want.

Experiences like this may not be universal, but any incident can be shared to other members of the KAP community and influence that person’s perception just as much as it would the victim of a rights violation.

Young women shared positive interactions with health care professionals, while also reflecting experiences of disrespect and paternalistic attitudes.

Young women in Homa Bay reported that their interactions with health care professionals are often constructive. At the same time, they shared instances of being disrespected on account of their age or sex, and several participants reported that coercion to test for HIV or pregnancy is commonplace. Several young women stated that NGOs “should stop pressuring their employee[s] to find HIV positive clients during testing” and that they themselves “have been pressured to test for HIV.” One woman even remarked, “HIV is nowadays a compulsory test.” Shared experiences informed perceptions: if another young woman in a community had a positive or negative experience with a particular health care provider or clinic, her experience had an impact on how other young women engaged with that provider or clinic. Young women were particularly concerned about social stigmatization, including as a result of being seen in or near an HIV clinic.[28]

Health care professionals recognized significant hurdles in building trust with KAP communities.

Health care professionals recognized that the unacceptance of KAP—socially and legally—impedes their HIV testing and health care utilization. Several professionals reported having received trainings on sensitization or human rights but noted that these trainings were inconsistent and under-resourced. One interviewee, a senior HIV policy expert in Kenya, reported that providers do receive training on human rights and National AIDS and STI Control Programme guidelines for HIV testing and notification services; however, no other health professional interviewee (including providers) personally recalled receiving formalized training or comprehensive human rights education. Several noted that the key issue for providers is attitude, with one interviewee stating, “That is the most important thing because they already have the technical trainings on the services that they need to get and everything else, the biology, it’s just all about the attitude which includes the human rights-based training.”

Interviewees praised community-based organizations and community partnerships in identifying and empowering peer leaders to encourage HIV testing, disseminate information, and form support groups. Interviewees recognized that legal awareness for patients’ human rights is underdeveloped, even where clinics or hospitals have written policies or standards of practice outlining the rights. The under-enforcement of protocol compliance may lead health care professionals to inadvertently violate rights, as may the zealous pursuit of a public health objective without consideration for human rights. The concern raised by some KAP that HIV testing contributed to reaching a quota was noted by a health care professional interviewee as well:

We often go for [rapid results initiatives], which sometimes motivate health care providers walking door to door where they get people in the villages, convince and test them. What is bringing the services down and making people fear is the habit looking for number! And giving people targets that you must test this number of people within this time. This has made it humanly difficult, and even worse for those found to be sero-positive.

Key findings for HIV testing

Perspectives from KAP indicate that Kenya’s HRBA is insufficiently understood and implemented at the point of care. The disconnect between what may be espoused as a norm or policy and what is experienced within the scope of that policy’s effectuation mirrors the rights context for KAP in Kenya. Health professional interviewees appeared sincere in their commitment to ensuring that all patients are treated well regardless of their demographics but recognized that incidents occur that might undermine trust building and fidelity to training or best practices. Speaking about the rural community context in particular, one health care professional from Homa Bay said:

I have seen a lot of people literally running away when you approach their villages because they associate your with previous project that came tested them, took their results away and left them there … little do the providers consider the psychological torture left with the individual after knowing their status.

Perceptions that HIV testing is required in order to access other services is troubling. One FSW participant said, “Many sex workers know their status because when you go to the hospital, the first mandatory thing they do before you see the doctor is being tested. If you don’t get tested, then you are not going to get any treatment.” Testing is, as a matter of Kenyan law and global norms, supposed to be entirely voluntary, yet concerns from each KAP study group challenged the voluntariness of HIV testing in Kenya.[29]

Participants from all study sites noted that fear of a positive result discourages some individuals from testing for HIV and accessing health services, underscoring the importance of counseling services. The importance of this finding is that it shows that these communities do not need to have personal experiences or patterns of experience that dissuade them from going to clinics—they need only be afraid of disrespect or a violation of their rights, including their dignity.[30] Addressing fear, then, must go beyond the mere presence of an HIV clinic or provider. One health care professional from Homa Bay summed it up well: “You have built it and they don’t come. Why? We have health facilities where [HIV testing] services are offered to everybody, but you still find young women and adolescent girls do not come … We want them to come for services, but we don’t want to go to them.”

A rights-based approach to HIV must begin with the rights themselves, through which the implementation and practice of Kenya’s HIV testing and treatment strategy is put to practice. KAP must feel trust for Kenya’s institutions, and that their rights will be respected and fulfilled by the community-facing agents of those institutions (including providers and health care workers). Trust building is predicated on understanding and compassion, which can emerge through histories of positive interaction and respectful engagement.[31] Kenya’s rights-based approach to HIV would improve through a rigorous educational structure for providers, paired with substantive community engagement.

Key findings for assisted partner notification services

Participants expressed mixed support for assisted partner notification services as a means to support case finding and treatment. Supporters, however, reflected that good counseling and engagement from their HIV caregivers before, during, and after disclosure can make the process acceptable. All participants felt it was important to disclose, but pressure to disclose early worked against their willingness to disclose at all.[32] Each KAP group recognized the potential for violence (physical, emotional, sexual, otherwise) in disclosing. For effective assisted partner notification services, substantial screening for such harms must be incorporated into the practices of HIV counselors and care providers, must address safety concerns, and must have PLWHV’s consent. KAP’s perceptions on assisted partner notification services are the same as for HIV testing: KAP’s trust (or distrust) in their provider is a significant factor in their willingness to consent and participate.

Community-based organizations’ KAP-friendly services: A model for the national HIV program

Participants’ universal praise for KAP-friendly services speaks to how providers and communities alike see the reach and approach of community-based organizations as an effective stratagem for accessing vulnerable populations.[33] All KAP groups and health professionals lauded the work of community-based organizations engaged in HIV care services, including in raising rights awareness. Although the limited capacities of these organizations’ KAP-friendly services inhibit their potential to deliver on Kenya’s HIV testing and treatment goals, in collaboration with local and national authorities they might be well positioned to support reform and sustained community outreach. Importantly, such collaborations may build trust and confidence in government-affiliated services and providers among those same communities, thereby leading to better health outcomes through better health care interactions.

Conclusion

In our study, KAP participants expressed concerning perspectives regarding their rights realization, with a high degree of inconsistency with respect to whether their rights are being respected. Kenya’s HIV health care professionals recognized that barriers in practice and policy hinder their outreach to and inclusion of KAP, in spite of individual provider attitudes that may be sensitized and welcoming. Experiences—whether personal, community based, or historical—influence KAP’s dispositions toward Kenya’s HIV care system and the extent to which they feel safe and confident in accessing testing and treatment. Kenya’s HRBA to HIV stands to improve in several discrete ways that could strengthen Kenya’s HIV programs by improving perceptions and trust among KAP for those same programs and the authorities tasked with implementing them.

KAP and health care providers both agree that HIV testing and notification service strategies need to include training “on [KAP] friendly services.”[34] Such training necessitates sensitivity toward, recognition of, and familiarity with KAP’s concerns, as well as follow-through to address them.[35] Training must also take into account historical trauma and reconcile the role that public health agencies, health care providers, and other authorities have played in fostering stigma and discrimination. Training programs and outreach efforts are more effective when led by trusted and respected individuals or organizations.[36] Community-based organizations working with KAP are well regarded and positioned to help improve public health programming, from workforce education to policy and implementation. In Mombasa, one health care professional suggested getting “health care workers to be attached to institutions, NGOs, [and] partners who actually provide care to KAP … for a week or so, so that they see [and] engage with [KAP] one-on-one [and] they realize [KAP] are individuals like any other.” Kenya’s human rights obligations compel a commitment to address long-standing distrust of government-affiliated facilities and providers.

Implementing an HRBA in practice requires that Kenyan authorities embrace accountable, uniform protocols to ensure that the human rights of KAP and all Kenyans are enjoyed. In particular, it requires ensuring that HIV testing and care is free from coercion and respects patient privacy and confidentiality. Ensuring that the health care workforce is sustainably sensitized to KAP issues would be a good step for strengthening Kenya’s HRBA and one that may be welcomed by health care providers.[37] KAP want health programs that empower providers with the literacy and tools they need to be duty-bearers who protect, respect, promote, and fulfill the rights of KAP and people living with HIV, as enumerated in Kenya’s laws and international treaties.[38] Enforcement and accountability will be key, and establishing mechanisms for reporting potential violations must go hand in hand with a process that addresses violations in accordance with human rights principles. Where essential, lawmakers and policy makers should revise, promulgate, and amend Kenya’s laws and regulations to ensure a robust legal environment for KAP’s rights realization.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support provided by KELIN staff and Tabitha Saoyo Griffith. We appreciate the guidance of Dr. Joe Zunt, University of Washington; Dr. Carey Farquhar, University of Washington; Dr. Matthew Kavanagh, Georgetown University; Theresa Odero, University of Nairobi; and Dr. Charles Muga, Kenya Medical Research Institute. We thank Hellen Moraa for her invaluable contributions in qualitative analysis. We also thank our interviewers for their contributions and the organizations they represent: Pascal Macharia Irungu, Dorothy Awuor Agalla, Festo Collins Owino, Fatma Ahmed Jeneby, and Hussein Abdalla Taib. Finally, we appreciate the support of our community-based organization partners and recognize their invaluable role in the formation, implementation, and utilization of this study: Gay and Lesbian Coalition of Kenya, Health Options for Young Men on HIV/AIDS/STI, Kisumu Sex Workers Alliance, Family Health Options Kenya, and Muslim Education and Welfare Association.

Funding

This project was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) research training grant number D43 TW009345, funded by the Fogarty International Center; the NIH Office of the Director Office of AIDS Research; the NIH Office of the Director Office of Research on Women’s Health; the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; the National Institute of Mental Health; and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. This project was additionally made possible by the Afya Bora Consortium Fellowship, which is supported by the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief through funding to the University of Washington under cooperative agreement U91 HA06801 from the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Global HIV/AIDS Bureau. Neiloy R. Sircar is currently supported by National Cancer Institute grant number CA-113710.

Ethical approval

Georgetown University’s Institutional Review Board (2018-1148) and the Kenya Medical Research Institute’s Scientific and Ethics Review Unit (Non-KEMRI No. 654 (2019)) approved this study. The University of Washington’s Institutional Review Board consented to Georgetown University’s approval.

Neiloy R. Sircar, JD, LLM, is a postdoctoral scholar at the University of California San Francisco, USA.

Allan A. Maleche, LLB, is Executive Director of the Kenya Legal and Ethical Issues Network, Nairobi, Kenya.

Please address correspondence to Neiloy Sircar. Email: nsircar@uw.edu.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2020 Sircar and Maleche. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

[1] United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, Introduction to a rights-based approach (July 2015). Available at https://socialprotection-humanrights.org/introduction-to-a-rights-based-approach/; UNAIDS, Human rights (2020). Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/topic/rights.

[2] A. Stangl, D. Singh, M. Windle, et al., “A systematic review of selected human rights programs to improve HIV-related outcomes from 2003 to 2015: What do we know?” BMC Infectious Diseases 19 (2019).

[3] See, for example, L. London, “What is a human-rights based approach to health and does it matter?” Health and Human Rights Journal 10/1 (2008).

[4] See Chr. Michelsen Institute, Operationalizing a rights-based approach to health service delivery (Dec 2013–2015). Available at

https://www.cmi.no/projects/1791-operationalizing-a-rights-based-approach-to-health.

[5] Ibid. See also Stangl et al. (see note 2).

[6] D. Barr, J. Amon, and M. Clayton, “Articulating a rights-based approach to HIV treatment and prevention interventions,” Current HIV Research 9/6 (2011).

[7] A. Yamin and A. Constantin, “A long and winding road: The evolution of applying human rights frameworks to health,” Georgetown Journal of International Law 49 (2017).

[8] Constitution of Kenya (2010), art. 43.

[9] HIV and AIDS Prevention and Control Act (2006), arts. 3(b), 6(3), 14, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22.

[10] Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 15: The Right of the Child to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, UN Doc. CRC/C/GC/15 (2013); Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, General Recommendation No. 24: Women and Health, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/1999/I/WG.II/WP.2/Rev.1 (1999); Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14: The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000).

[11] East African Community, HIV Prevention and Management Act (2012). Available at https://www.kelinkenya.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/EAC-HIV-ACT-2012.pdf.

[12] AVERT, HIV and AIDS in Kenya (April 2020). Available at https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/kenya.

[13] Government of Kenya, Kenya’s national HIV survey shows progress towards control of the epidemic [press release] (February 20, 2020). Available at http://www.health.go.ke/kenyas-national-hiv-survey-shows-progress-towards-control-of-the-epidemic-nairobi-20th-february-2020/.

[14] AVERT (see note 12).

[15] G. Githuka, W. Hladik, S. Mwalili, et al., “Populations at increased risk for HIV infection in Kenya: Results from a national population-based household survey, 2012,” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 55/Suppl 1 (2014), pp. S46–S56. See also National AIDS Control Council, Kenya AIDS response progress report 2016 (Nairobi: Ministry of Health, 2016), p. 51; National AIDS Control Council, Kenya AIDS response progress report 2018 (Nairobi: Ministry of Health, 2018).

[16] US Department of State, U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief: 2020 country operational plan guidance for all PEPFAR Countries (2020) (Washington, DC: PEPFAR, 2020), p. 2. See also A. Strangl, M. Sebany, C. Kapungu, et al., Technical and programmatic considerations for index testing and partner notification for adolescent girls and young women: Technical report (Washington, DC: YouthPower Learning, 2019).

[17] World Health Organization, Consolidated guidelines on HIV testing services (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015).

[18] National AIDS and STI Control Programme, The Kenya HIV testing services guidelines (Nairobi: Ministry of Health, 2015).

[19] See, for example, S. Dalal, C. Johnson, V. Fonner, et al., “Improving HIV test uptake and case finding with assisted partner notification services,” AIDS 31/13 (2017), pp. 1867–1876.

[20] See, for example, S. Kalichman, C. Mathews, M. Kalichman, et al., “Perceived barriers to partner notification among sexually transmitted infection clinic patients, Cape Town, South Africa,” Journal of Public Health 39/2 (2017), pp. 407–414.

[21] UNAIDS, Women and HIV: A spotlight on adolescent girls and young women (Geneva: United Nations, 2019). See also S. Mathur, J. Okal, M. Musheke, et al., “High rates of sexual violence by both intimate and non-intimate partners experienced by adolescent girls and young women in Kenya and Zambia: Findings around violence and other negative health outcomes,” PLoS One 13/9 (2018).

[22] E. Moyer, E. K. Igonya, R. Both, et al., “The duty to disclose in Kenyan health facilities: A qualitative investigation of HIV disclosure in everyday practice,” Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS 13/10/Suppl 1 (2013), pp. S61, S64, S66–S70.

[23] I. Maeri, A. Ayadi, M. Getahun, et al., “‘How can I tell?’ Consequences of HIV status disclosure among couples in eastern African communities in the context of an ongoing HIV ‘test-and-treat’ trial,” AIDS Care 28/Suppl 3 (2016), pp. 62–64.

[24] J. Kinuthia, B. Singa, C. McGrath, et al., “Prevalence and correlates of non-disclosure of maternal HIV status to male partners: A national survey in Kenya,” BMC Public Health 18 (2018).

[25] N. Sircar, T. Griffith, and A. Maleche, “Assessing a human rights-based approach to HIV in Kenya,” Health and Human Rights Journal 21/1 (2019).

[26] S. Golub and K. Gamarel, “The impact of anticipated HIV stigma on delays in HIV testing behaviors: Findings from a community-based sample of men who have sex with men and transgender women in New York City,” AIDS Patient Care 27/11 (2013).

[27] Kenya Legal and Ethical Issues Network, Report: Trends in HIV & TB human rights violations and interventions (Nairobi: Kenya Legal and Ethical Issues Network, 2019).

[28] S. Treves-Kagan, W. Steward, L. Ntswane, et al., “Why increasing availability of ART is not enough: A rapid, community-based study on how HIV-related stigma impacts engagement to care in rural South Africa,” BMC Public Health 28/16 (2016). See also S. Treves-Kagan, A. El Ayadi, A. Pettifor, et al., “Gender, HIV testing and stigma: The association of HIV testing behaviors and community-level and individual-level stigma in rural South Africa differ for men and women,” AIDS and Behavior 21/9 (2018).

[29] HIV and AIDS Prevention and Control Act (2006); World Health Organization (see note 17); National AIDS and STI Control Programme (see note 18).

[30] Golub and Gamarel (see note 26). See also K. Gamarel, K. Nelson, R. Stephenson, et al., “Anticipated HIV stigma and delays in regular HIV testing behaviors among sexually-active young gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men and transgender women,” AIDS and Behavior 22/2 (2018).

[31] J. Kakietek, T. Geberselassie, B. Manteuffel, et al., “It takes a village: Community-based organizations and the availability and utilization of HIV/AIDS-related Services in Nigeria,” AIDS Care 25/Suppl 1 (2013).

[32] See generally C. Obermeyer, P. Baijal, and E. Pegurri, “Facilitating HIV disclosure across diverse settings: A review,” American Journal of Public Health 101/6 (2011).

[33] UNAIDS, Expanding access to HIV treatment through community-based organizations (Geneva: UNAIDS, 2005).

[34] US Department of State, U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief: Kenya country operational plan 2018 strategic direction summary (Apr 2018) (Washington, DC: PEPFAR, 2018), pp. 41–42.

[35] E. M. van der Elst, A. D. Smith, E. Gichuru, et al., “Men who have sex with men sensitivity training reduces homoprejudice and increases knowledge among Kenyan healthcare providers in coastal Kenya,” Journal of the International AIDS Society 16/Suppl 3 (2013).

[36] Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria, Technical brief: HIV, human rights, and gender equality (Geneva: Global Fund, 2019).

[37] E. M. van der Elst, E. Gichuru, N. Muraguri, et al., “Strengthening healthcare providers’ skills to improve HIV services for MSM in Kenya,” AIDS 29 (2015).

[38] UNAIDS, Guidance note: Key programmes to reduce stigma and discrimination and increase access to justice in national HIV responses (Geneva: UNAIDS, 2012).