Volume 21/1, June 2019, pp 149- 156

Jacob Armato, Laura Block, Mason Flannagan, Eric Obscherning, and Lori Diprete Brown

Introduction

Interest in global health at American universities has increased dramatically over the past 15 years.1 International fieldwork is an integral component of global health programming, with students traveling for humanitarian reasons, learning opportunities, and a need to meet graduate program admissions requirements.2 For example, 73% of American medical schools require or encourage clinical experience by applicants despite committee members’ “significant concern” about the potential for unlicensed students providing care, such as surgical procedures, to patients in other countries during international health trips.3 The academic community has critiqued the ethical challenges of these short-term trips, but to date undergraduate students are absent from these discussions.4

Mirroring national trends, the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW-Madison) has experienced growth in global health programming, including an undergraduate- and graduate-level global health minor with faculty-mentored fieldwork. These programs involve rigorous screening, training, reflection, and discussion of cross-cultural issues and ethics. During travel, faculty emphasize learning as the primary goal. Outside of global health programming, students engage in extracurricular global health work through registered student organizations (RSOs). No well-recognized mechanisms exist for preparing students traveling with RSOs, which, by design, operate with autonomy and self-governance.5 The university’s role and responsibility in providing guidance for these trips is ambiguous.

UW-Madison has more than 1,000 RSOs.6 Of these, 30% have a health focus and 10% a specific interest in global health.7 The number and nature of short-term trips outside of university programming are not tracked, but their existence is known among students and faculty. RSO members share stories of providing unqualified care when recruiting, reflecting in class, or crafting post-baccalaureate applications. Details have not been disclosed to protect patient and student confidentiality, but comparable stories of students delivering babies, providing medications requiring long-term monitoring, and assisting in surgical procedures have been reported nationally.8 Additionally, 85% of pre-health advisors nationally report knowledge of these undergraduate trips, and 89% acknowledge concern about students providing unqualified care.9

Though guidelines for global health trips exist, the majority are directed toward graduate and medical students.10 Some organizations, such as the Association of American Medical Colleges, have responded by tailoring guidelines to undergraduate students but do not present mechanisms for translating such guidelines to the extracurricular context.11 The Forum on Education Abroad has also developed guidelines for undergraduate global health trips, but these guidelines target institutions, not students.12 None of the guidelines are tailored to independent bodies such as RSOs, even though extracurricular global health trips take place at universities across the country. Universities may be constrained in addressing RSO trips due to the legal void within which RSO-led trips take place.

Recognizing this void, we developed guidelines for undergraduate RSOs and methods for their distribution. Our work was inspired and informed by a variety of exemplars, traditional medical ethics, and human rights principles. While not a systematic rights-based program, our effort is compatible with further development in this direction over time. We paid particular attention to Thomas Pogge’s ethical framework—a global expansion of Rawlsian philosophy—which recognizes how interconnected global systems and institutions create inequitable distributions of power, resources, and suffering.”13 Additionally, we relied heavily on traditional medical ethics, which are guided by the Hippocratic Oath and grounded in absolute virtues such as empathy and beneficence.14 However, medical ethics are largely unidirectional in nature, centering on patients and certain aspects of their health while often missing broader social determinants of health.15 A human rights framework bridges this gap, locating health within a broader context of interdependent and indivisible rights and recognizing a larger number of players in the global arena: providers, students, and patients alike.16 Further, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights makes clear that all humans have a right to basic entitlements, including health.17 The delivery of unqualified care challenges the human right to accessible, affordable, appropriate, and quality health care as stipulated in General Comment 14 of the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.18 Ethical lapses challenge patients’ rights and dignity. This resonated with our personal convictions regarding social justice, which are informed largely by the Alma-Ata Declaration and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.19

This paper describes our (1) design of guidelines for undergraduate students traveling on short-term global health trips outside of academic programming, and (2) implementation of a novel, sustainable, student-led program to engage with and discuss these guidelines.

Methods

In 2014, we discussed the need for ethical guidelines and avenues for their distribution. We reviewed existing guidelines, theoretical underpinnings, and models of distribution; conducted an internal analysis to identify stakeholders; and reviewed policies regarding RSO oversight, travel, and funding. Finally, we tailored these guidelines to undergraduate RSOs and constructed a program for the guidelines’ distribution. Evaluation was performed via surveys and informed program improvements.

The design process focused on fostering undergraduate students’ awareness of ethical challenges and the need to prevent harm during travel. Given the self-governing and autonomous nature of RSOs, we chose a reflective process of learning and discernment rather than a regulatory approach. The voluntary, extracurricular nature of RSO activities also influenced the design, triggering the development of a brief educational program to raise awareness and foster positive decision-making. The aim was to create pragmatic and accessible guidelines and accompanying educational program based on a set of central driving principles.

Results

Literature review findings

Our literature review revealed a number of guidelines, perspective pieces, and case studies, which we analyzed for key components and principles. Of note was John Crump and Jeremy Sugarman’s guidelines for global health training.20 Since performing our original literature review in 2014, there has been growth in the global health ethics field, illustrated by a recent scoping review of guidelines for global health trips.21

Internal analysis findings

At UW-Madison, we identified 172 RSOs with “global health” in their name or description, 348 with “pre-health” in their name, and 156 with a self-described “medical” interest. Most of these RSOs function as independent entities. Others function as chapters of national volunteer organizations; however, student members of these RSOs often described a paucity of guidance from the parent organizations. The UW-Madison student government allocates funding to RSOs for travel but does not have additional screening for health-related trips.

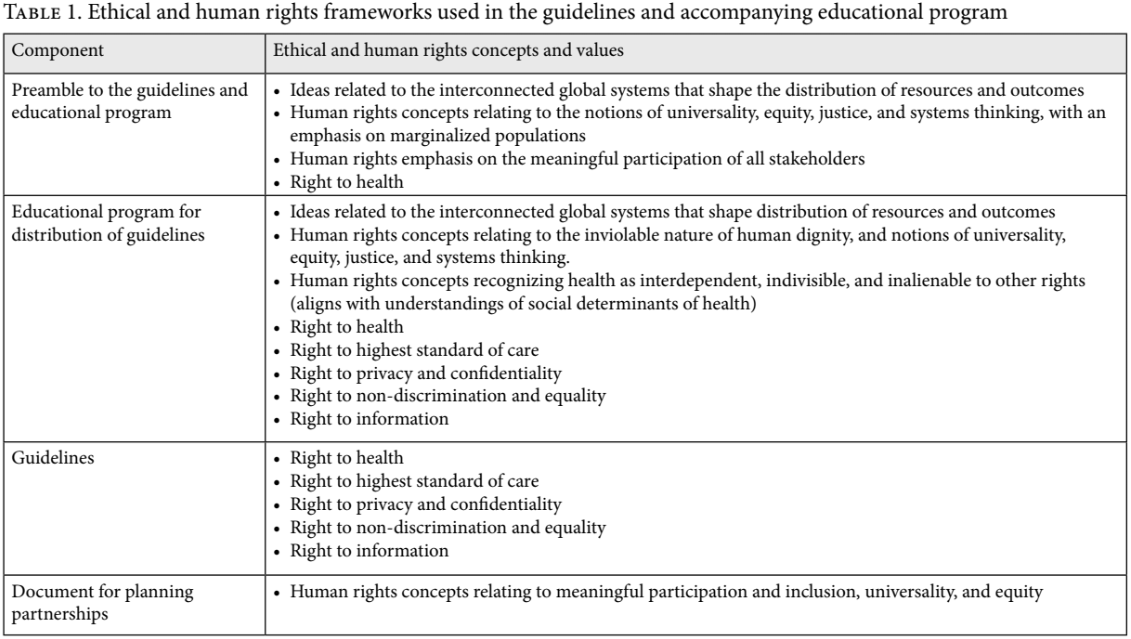

Alignment with ethical and human rights frameworks

By going beyond traditional medical ethics, we engaged with a broad body of literature and subsequently reflected on a wide set of concepts and values (Table 1) throughout the ethical guidelines and accompanying educational program, both implicitly and explicitly.22

Guideline development

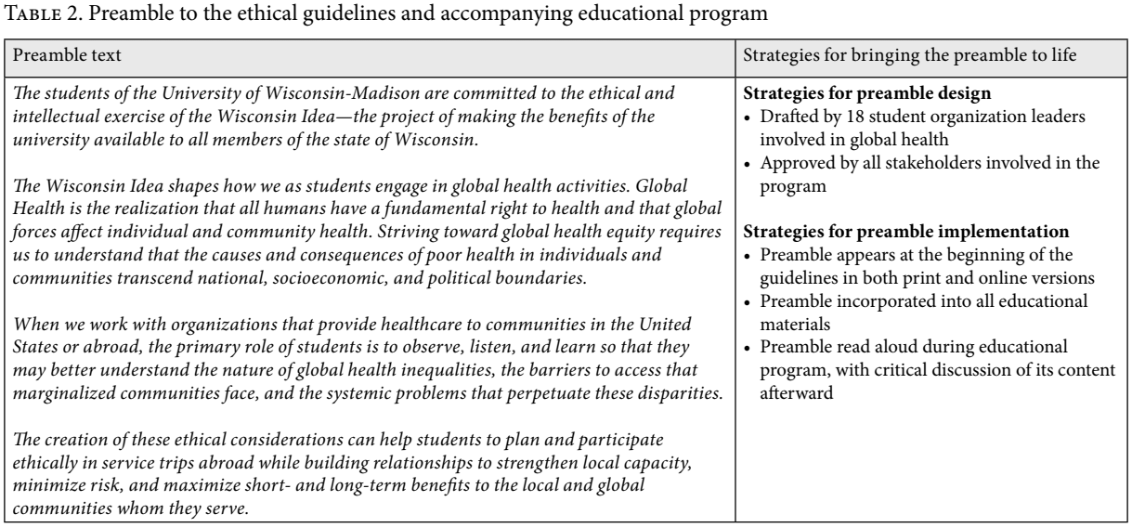

Eighteen student organizations and several mentors from the UW-Madison Global Health Institute, Center for Pre-Health Advising, and School of Medicine and Public Health met to develop the ethical guidelines, which were framed by a preamble inspired by a review of key ethical and human rights frameworks (Table 2). Our strategies for designing the preamble and incorporating it into the guidelines and programming are highlighted.

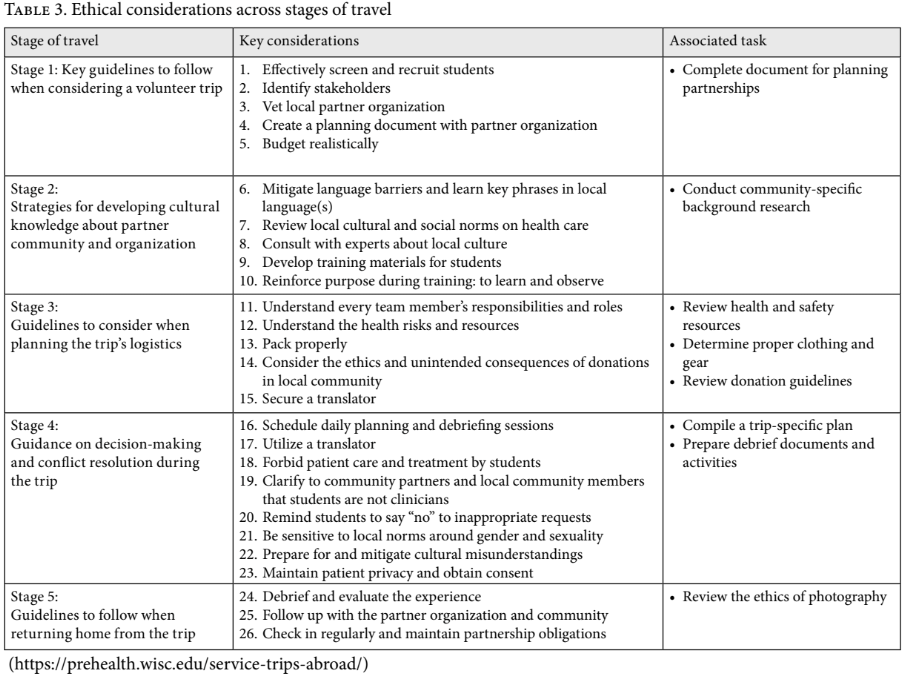

As a result of several meetings, we drafted 26 ethical considerations pertaining to five stages of travel (Table 3). These considerations largely represent normative principles and practical steps. The Office of Legal Affairs reviewed the final draft, adding a statement disclaiming any responsibility or liability and advising a change in the title from “Ethical Guidelines” to “Ethical Considerations.”

Educational program development and implementation

Educational program development and implementation

The guidelines were delivered through a one-hour educational program conducted via a self-directed, lateral approach, as informed by andragogical learning theory.23 The educational program aimed to begin a conversation that would continue throughout the planning and implementation of any subsequent RSO travel. The approach incorporated teaching principles specific to service-learning trips, focusing on (1) mitigating power dynamics via a peer-to-peer approach, (2) reframing ethics as a learning process on the individual and collective level, (3) approaching conflict as an “opportunity,” not a “problem,” and (4) communicating strategically in a supportive, non-punitive manner.24 Attendance was incentivized by providing food, opportunities to engage with faculty, and a certificate of program completion. Student leaders also worked with the UW-Madison student government to draft a bylaw amendment that would require student groups to complete the educational program before receiving travel grants for global health trips. The bylaw amendment passed with unanimous support.

We reached out to all global health RSOs at the start of each year to offer the program, and between fall 2016 and spring 2017 offered the program three times and provided additional individual meetings. In total, 23 student organization leaders completed the program. Each leader made a verbal commitment to review the ethical considerations, articles, and case studies with their larger groups. Altogether, these leaders represented upwards of 1,500 undergraduate students.

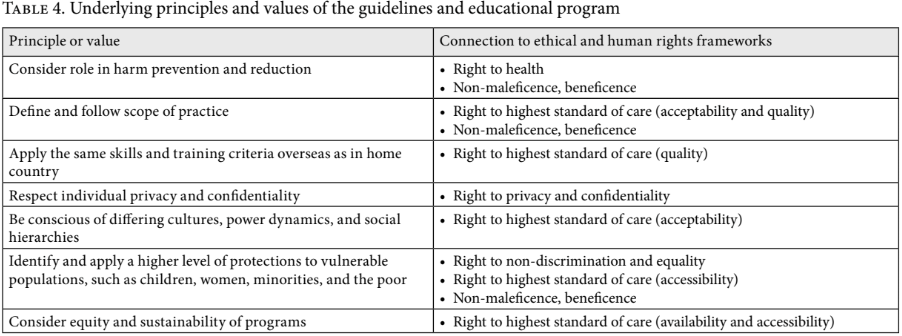

During the program, authors and RSO student leaders engaged in conversation on the principles underlying the preamble and guidelines. Seven distinct principles and values were identified (Table 4).

The effect of requiring RSOs to complete the educational program to receive travel grants was assessed through a review of student government records. Of the 23 student organizations completing the program during the 2016–2017 pilot year, four had applied for travel grants through the student government. Upon review, these were the same four organizations flagged in student government records as seeking finance for global health trips. The remaining 19 RSOs indicated the following reasons for attendance: plans to travel with personal funding, plans for future travel grant applications, and interest in the topic.

Challenges to design and implementation

Challenges to design were many and included the following: understanding legal ramifications related to the autonomy of RSOs, locating RSO numbers and data, and securing institutional support. In response to student leader turnover, we requested and were granted support for a long-term internship within the Center for Pre-Health Advising.

Challenges to implementation included busy student schedules, difficulty reaching the targeted student audience, navigating the disclosure of unethical practices, and barriers to comprehension for attendees. Comprehension was hindered by the difficulty of the content, cognitive dissonance, and the belief that “some help is better than none.” Despite this, students demonstrated interest and willingness to monitor and enforce their own ethical practice.

Discussion

The success to date and future potential of the educational program are likely due to unique features of its design that draw on adult learning principles and participatory frameworks.25 Rather than employing regulatory language and a punitive framework, the program frames the student journey as a “coming into awareness” and situates ethical quandaries as a part of global health work that all must navigate using self-regulation and discernment. Further, a student-led, peer-to-peer advising model with an emphasis on participatory learning and culture change mitigates hierarchal power dynamics that can undermine trust. Anecdotal evidence from RSO leaders on critical conversations among members and with parent volunteer organizations has suggested that this design may have the potential to change individual and group behavior. In future project phases, pre- and post- program evaluation will be necessary to accurately capture the impact of this model at scale and the effect on student organization culture.

Equally important is the pragmatic, procedural guidance that is complemented by discussions on ethics and human rights principles. During the educational program, the notion of justice—highlighted in human rights frameworks—resonated with student participants. Further, the application of a human rights framework, particularly the inviolate and inalienable dignity of people, and the AAAQ (Availability, Accessibility, Acceptability and Quality) standards helped students think critically about their beliefs that “one’s poverty outweighs one’s dignity.” Future work will make these ideas explicit throughout the guidelines and educational program, having students engage directly with key human rights principles rather than confining the principles to the discernment exercises and implicit design.

Finally, to ensure coverage of RSOs at the university level, a better screening process is needed to identify all RSOs engaging in independent global health trips. Groups that do not brand their trips as “health trips” or that do not request funding from RSO resource pools may not be identified with current procedures.

Conclusion

This paper describes the first student-led development and implementation of ethical guidelines for non-academic RSO global health trips and details the challenges to design and uptake for universities and students wishing to replicate the model.

The ability to partake in a global health trip is predicated on a host of material and cultural privileges, including disposable income to travel internationally while attaining a college degree. Beyond this is a broader privilege that gives one power in influencing another’s well-being. By engaging internationally with marginalized populations in health-related settings, students enter into spaces with the power to make decisions that will affect the health of individuals and communities. Presented with difficult choices, they need an ethical lens through which to evaluate the impact on the people they wish to serve. They need to consider whether those choices protect or challenge those individuals’ rights to health and quality care. Our program—by bringing to light the unintended consequences of unqualified care, disjointed interventions, and misbalanced partnerships in a non-punitive, peer-to-peer format—helps undergraduate students do just that. By collectively reviewing the preamble of the ethical considerations at the outset of the program, students begin their intellectual journey grounded in the understanding that health is a human right. This conviction is the sine qua non of our program.

Our initiative addresses ethical breaches by RSOs at UW-Madison, yet this problem extends to other universities throughout the United States where similar legal voids exist. A program by students for students can enter critical spaces and discussions that institutions and staff, by nature, cannot traverse. This both increases the potential for impactful change and reduces the barrier for program replication. There is no shortage of passionate undergraduate students seeking an opportunity to make a difference locally and globally.

Replication at other universities would require adaptation of the guidelines and educational program and consideration of local policies and stakeholders. Additionally, a careful review of the challenges to design and implementation might improve future rollout. The proliferation of student-led systems such as this one would ensure that these commonplace trips continue to spur interest in global health and foster cross-cultural collaboration without compromising the ideals of justice and equity at the heart of global health and human rights.

Acknowledgments

We would like to dedicate this work to the late Robin Mittenthal, mentor and advisor to countless global health students and champion of ethical and sustainable relationships between communities and universities. In addition, we would like to thank Emi Kihslinger, Daniel Simon, James Conway, Sweta Shrestha, Susan Nelson, Dija Selimi, Sarah Paige, Claire Wendland, and the student government of UW-Madison.

Jacob Armato, BS, is a recent graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Madison College of Letters and Sciences, Madison, USA.

Laura Block, BS, is a current student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Nursing, Madison, USA.

Mason Flanagan is an undergraduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison College of Letters and Sciences, Madison, USA.

Eric Obscherning, BS, is a graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Madison College of Letters and Sciences, Madison, USA.

Lori DiPrete Brown, MSPH, MTS, is associate director of the Global Health Institute and a distinguished faculty associate in civil society and community studies in the School of Human Ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA.

Please address correspondence to Jake Armato. Email: jsarmato1@gmail.com.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2019 Armato, Block, Flanagan, Obscherning, and DiPrete Brown. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- J. A. Crump, J. Sugarman, and the Working Group on Ethics Guidelines for Global Health Training, “Ethics and best practice guidelines for training experiences in global health,” American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 83/6 (2010), pp. 1178–1182.

- D. Holmes, L. E. Zayas, and A. Koyfman, “Student objectives and learning experiences in a global health elective,” Journal of Community Health 37/5 (2012), pp. 927–934.

- Group on Student Affairs, Committee on Admissions, Clinical experiences survey summary (Washington DC: Association of American Medical Colleges, 2016).

- M. DeCamp, “Scrutinizing global short-term medical outreach,” Hastings Center Report 37/6 (2007), pp. 21–23.

- University of Wisconsin-Madison, Student organization resource and policy guide – UW-Madison (2018). Available at https://guide.cfli.wisc.edu.

- University of Wisconsin-Madison, Organization –Wisconsin Involvement Network (WIN) (2018). Available at https://win.wisc.edu/organizations.

- UW-Madison Wisconsin Involvement Network, Search results (2019). Available at https://win.wisc.edu/organizations?categories=10873&query=global%20health.

- K. Fischer, “Some health programs overseas let students do too much, too soon,” Chronicle of Higher Education (2013). Available at https://www.chronicle.com/article/Overseas-Health-Programs-Let/142777.

- J. Evert, T. Todd, and P. Zitek, “Do you GASP? How pre-health students delivering babies in Africa is quickly becoming consequentially unacceptable,” Advisor (2015).

- J. N. Lasker, M. Aldrink, R. Balasubramaniam, et al., “Guidelines for responsible short-term global health activities: Developing common principles,” Globalization and Health 14/18 (2018). Available at https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-018-0330-4.

- Association of American Medical Colleges, Guidelines for premedical and medical students providing patient care during clinical experiences abroad (Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges, 2011).

- Forum on Education Abroad, Guidelines for undergraduate health-related experiences abroad (Carslisle: Forum on Education Abroad, 2018).

- T. Pogge, World poverty and human rights: Cosmopolitan responsibilities and reforms (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2002), pp. 15–16.

- R. Baker, “The history of medical ethics,” in W. F. Bynum and R. Porter (eds), Companion encyclopedia of the history of medicine (London: Routledge, 1993), pp. 852–887.

- T. Ezer and J. Cohen, “Human rights in patient care: A theoretical and practical framework,” Health and Human Rights 15/2 (2013) pp. 7–19.

- United Nations Children’s Fund, Human rights-based approach to programming (New York: United Nations Children’s Fund, 2003), pp. 1–3.

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights, G.A. Res. 217A (III) (1948), art. 25.

- Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000), art. 12.

- Declaration of Alma-Ata, International Conference on Primary Health Care (1978); Universal Declaration of Human Rights, G.A. Res. 217A (III) (1948).

- Crump et al. (see note 1).

- Lasker et al. (see note 10).

- FXB Center for Health and Human Rights, Health and human rights resource guide (Cambridge, MA: FXB Center for Health and Human Rights, 2019). Available at https://www.hhrguide.org/2014/02/27/table-a-and-b-patient-care.

- M. S. Knowles, The modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Cambridge Adult Education, 1988).

- W. B. Ventres and C. L. Wilson, “Beyond ethical and curricular guidelines in global health:

Attitudinal development on international service-learning trips,” BMC Medical Education 15/68 (2015). - Knowles (see note 23).