Benjamin Mason Meier, Oscar A. Cabrera, Ana Ayala, Lawrence O. Gostin

Health and Human Rights 14/1

Published June 2012

Abstract

The O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University, the World Health Organization, and the Lawyers Collective have come together to develop a searchable Global Health and Human Rights Database that maps the intersection of health and human rights in judgments, international and regional instruments, and national constitutions. Where states long remained unaccountable for violations of health-related human rights, litigation has arisen as a central mechanism in an expanding movement to create rights-based accountability. Facilitated by the incorporation of international human rights standards in national law, this judicial enforcement has supported the implementation of rights-based claims, giving meaning to states’ longstanding obligations to realize the highest attainable standard of health. Yet despite these advancements, there has been insufficient awareness of the international and domestic legal instruments enshrining health-related rights and little understanding of the scope and content of litigation addressing these rights. As this accountability movement evolves, the Global Health and Human Rights Database seeks to chart this burgeoning landscape of international and regional instruments, national constitutions, and judgments for health-related rights. Employing international legal research to document and catalogue these three interconnected aspects of human rights for the public’s health, the Database’s categorization by human rights, health topics, and regional scope provides a comprehensive compilation of health and human rights law. Through these categorizations, the Global Health and Human Rights Database serves as a basis for analogous legal reasoning across states to serve as precedents for future cases, for comparative legal analysis of similar health claims in different country contexts, and for empirical research to clarify the impact of human rights judgments on public health outcomes.Introduction

National legal frameworks that uphold health-related human rights encourage a rights-based public policy that gives meaning to international treaty obligations and provides for individual causes of action, ensuring human rights accountability for global health advancement. Accordingly, such national law has laid the groundwork for a rapidly expanding accountability movement at the intersection of health and human rights, empowering individuals and groups to raise human rights claims and providing rights-based enforcement for health. Supporting the implementation of human rights, these cases have been shown to provide essential medicines to the sick, to alleviate state infringements on individual liberties, and to restrict harmful determinants of the public’s health. This expanding case law, based upon international instruments and codified in national law, has only begun to show tangible gains in national health policy and measurable effects on public health outcomes. As this jurisprudence flourishes, human rights are elevating from principle to practice, concretizing legal obligations through judicial interpretation and implementing universal norms through national policy.

However, despite international evolution in health-related human rights and jurisprudential advances in creating accountability for these rights, there exists no compilation of either the substantive content of these legal instruments or the enforcement claims litigated under these human rights standards. As this accountability movement grows, there arises an imperative not only to increase awareness of the international, regional, and domestic legal instruments protecting health-related human rights, but to establish precedent for rights-based claims, develop “best practices” in human rights enforcement, and harmonize practices conducive to the effective realization of human rights in health. Where individual rights-based claims have proven successful in reforming national policies, these claims can be compared across nations and issues–developing consistency in human rights judgments, facilitating universality through rights-based policy, and assessing causality for public health outcomes.

Through the cooperative efforts of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University (O’Neill Institute), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Lawyers Collective, a leading public interest service provider in India, an online Global Health and Human Rights Database has been developed to document and catalogue the legal intersection of health and human rights, creating searchable resources to identify:

1) Judgments

The judgments section of the Database provides a systematic survey of jurisprudence addressing health-related rights claims, categorizing judgments on the basis of human rights, health topics, and regional scope and thereby mapping the interaction between health and human rights in national, regional, and international case law.2) International and regional instruments

The international and regional instruments section of the Database illustrates how health-related rights are recognized in international and regional legal frameworks, detailing legally binding and non-binding instruments (the latter referred to as “soft law”) under international human rights law.3) National constitutions

The national constitutions section of the Database identifies provisions of national constitutions that enshrine health-related human rights, demonstrating how health-related rights have been recognized as basic legal principles capable of supporting actionable claims.1

As practitioners and scholars examine the landscape of health-related rights through these three cross-linked sections, this Database can provide a basis for assessments of rights-based accountability efforts, allowing for legal reasoning across national contexts to serve as precedents in future cases and for comparative analysis of similar health claims in different country contexts. Given the growth of this Database, it is expected that these resources may form the basis of future research to clarify the impact of health-related rights claims on public health outcomes.

Background

As part of an evolving interaction between human rights law and national health policy, human rights have come to structure legal accountability for national policy through justiciable obligations. Supported by a wide range of global institutions, the development of a database to catalogue human rights jurisprudence for health will promote the realization of health-related rights at domestic, regional, and international levels.

Health and human rights

Human rights offer a powerful normative framework to advance justice in health.2 Construing health disparities as “rights violations” offers international standards by which to frame government obligations and evaluate social justice through legal enforcement.3 First elucidated by the 1948 Constitution of the World Health Organization, states declared that “the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being,” defining health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”4 Building from this expansive WHO standard, through the international legal institutions developed since the end of the Second World War and the founding of the United Nations (UN), international human rights law has identified individual rights-holders and their entitlements and corresponding duty-bearers and their obligations, empowering individuals to seek legal redress for health violations rather than serving as passive recipients of government benevolence.5,6

Codified seminally in the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights—providing for “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health”—the human right to health has evolved in subsequent international instruments to influence health through an expansive and reinforcing set of international treaties, regional instruments, and national laws and policies.7 As a framework for global health governance, UN agencies, development organizations, and advocacy groups have increasingly invoked a “rights-based approach to health,” implementing the right to health and rights to various underlying determinants of health as a means to frame the legal and policy environment, integrate core principles into programming, and facilitate accountability for international norms.8,9,10 Where scholars and practitioners long debated the enforceability of social and economic rights—with these debates grounded largely in the politics of the Cold War—the 1990s brought with it a global consensus that all human rights are universal, indivisible, interdependent, and interrelated.11 Interpreting these interconnected human rights and correlative government duties, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) issued a General Comment in 2000 to provide authoritative understanding of state obligations in accordance with the right to health.12 As the CESCR clarified these obligations in General Comment 14, the right to health depends on a variety of interconnected rights, beginning with preventive and curative health care and expansively encompassing underlying health-related rights to food, housing, work, education, human dignity, life, non-discrimination, equality, prohibitions against torture, privacy, access to information, and freedoms of association, assembly, and movement.

Implementing this evolving interpretation, states commit to respect, protect, and fulfill the right to health, with human rights now understood to offer a normative framework for national health policy. As states have moved to incorporate the right to health and a wide range of health-related rights under national constitutions and laws, this rights-based approach to health is explicitly shaping government policy efforts.13,14,15 Yet rights remain meaningless without accountability. With an expanding movement to hold governments accountable for the implementation of these health-related rights, litigation has served as a means to enforce government obligations with respect to both de jure and de facto violations of human rights, evaluating national policies and securing access to justice for individual health needs.16

Litigation as a strategy to enhance accountability

Litigation has become a central strategy in pressing state accountability for realizing international treaty obligations and national legal commitments to health-related human rights, providing causes of action for individual health needs and empowering individuals to raise human rights claims for the public’s health. Supporting efforts to facilitate rights-based accountability through national political advocacy and international treaty monitoring, a rapidly expanding enforcement paradigm has arisen at the intersection of human rights litigation and national health policy.17 Where experience has shown that human rights are justiciable for health, litigation before national, regional, or international courts (or quasi-judicial bodies, such as the United Nations Human Rights Committee and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights) allows individuals to seek impartial adjudication from a formal institution with remediation authority.18 With judgments thought to deliver benefits beyond the individual claimant, such cases are often sought to reform policies that impact the health of entire classes of people. These cases, based upon international and regional human rights instruments and national legal provisions, have only begun to show tangible gains in national health policy, with tribunals around the world expansively exercising their authorities to interpret human rights, clarify individual claims, and prescribe national policies in response to leading threats to health.19,20

Incorporating determinants of health, litigation for health-related human rights includes all of the civil, cultural, economic, political, and social rights that affect health. Where the justiciability of social and economic rights is now a reality in many states, the post-Cold War consensus on the interconnectedness of human rights, as expressed in the Vienna Declaration and memorialized in health through General Comment 14, has recognized that socioeconomic rights can be enforced even in their progressive realization.21 Often in contentious dialectic with the political branches of government, judgments have advanced the interests of resurgent social movements against recalcitrant government actors.22 Spurred on by the “exceptional” rights-based response to HIV/AIDS—beginning in freedoms from discrimination and transitioning to access to essential medicines—litigation has produced prominent health policy reforms.23,24,25 With human rights influencing a wide range of accountability mechanisms for the progression of human dignity—including international monitoring bodies, human rights indicators, and “naming and shaming” advocacy—jurisprudence has the ability to complement and concretize these other mechanisms for the realization of rights.26 As this accountability movement develops across multiple countries, with courts often serving as a last resort in protecting the public’s health, human rights are translated from principle to practice through judicial action.

In the past decade, the number of such cases has increased dramatically throughout the world, especially in middle- and low-income countries.27 An “integrated approach” to rights-based freedoms and entitlements has led to the adjudication of health issues pursuant to an expanding range of health-related human rights claims, from freedom from discrimination in the health sector to fulfillment of the right to water and sanitation.28 Likewise, these cases have focused on an expanding range of health topics, including, among others, access to health services and medication; public health emergencies; and underlying determinants of health. Despite criticism that this rights-based litigation has distorted national health governance, there seems to be a clear trend toward more (and more progressive) cases–a trend that is likely to accelerate given the creation of a supranational individual complaint mechanism under the 2008 Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.29,30 Yet in advancing this litigation to realize health-related rights—whether brought by individuals with a specific health claim or by advocates seeking to hold governments accountable for public health obligations—there is limited understanding of the legal strategies for litigation success, the policy effects across varied national health systems, and the health implications of cases.

Cooperative efforts to address human rights litigation

As the right to health gained increased attention in the new millennium and began to crystallize at the international and national levels, WHO began to compile judgments and domestic, regional, and international legal instruments to understand the contours of health-related rights, particularly the right to health. With both the institutional authority and legal capacity to establish international coordination and cooperation for rights-based approaches to health, WHO has undertaken efforts to mainstream human rights as a cross-cutting policy.31 Collaborating with organizations, scholars, and advocates at the intersection of health and human rights, WHO has encouraged studies to facilitate a deeper understanding of the scope and content of health-related rights, reaching out to academic institutions and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to undertake comparative research and analysis on the application of human rights to health. Recognizing that litigation for health-related rights can take many forms—diverging according to the basis of the right, the type of judicial proceedings, the reasoning of the judgment, and the implementation of the decision—WHO conceptualized a database on rights-based judgments as a useful tool to survey human rights law in national judicial decisions. By cataloguing human rights for health in national, regional, and international judgments, international and regional instruments, and national constitutions, access to this comparative research could provide easily accessible information to a wide range of stakeholders working health-related human rights.

This Global Health and Human Rights Database arises through the cooperative efforts of the O’Neill Institute, WHO, and the Lawyers Collective to develop a searchable online database that would provide a systematic survey of human rights jurisprudence for health and would catalogue the interaction between health and human rights in national, regional, and international judgments, international and regional instruments, and national constitutions. Following up on the WHO Database on Health and Human Rights Actors—which surveys organizations working at the intersection of health and human rights—this Database aims to provide comprehensive access to human rights law for the public’s health.32 Based upon an initial legal database developed by the O’Neill Institute, WHO, and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) to map the legal and jurisprudential landscape at the intersection of public health and human rights, the Global Health and Human Rights Database strengthens state capacity to develop rights-based approaches to health and strengthens civil society resources to create accountability for state obligations to realize the highest attainable standard of health and other health-related human rights. Merging the O’Neill Institute, WHO, and UNFPA database project on health and human rights law with a Lawyers Collective database project on health-related litigation, this expanded partnership—currently working with over 50 partners globally, including NGOs, academics, and private researchers—has brought together health-related rights judgments, instruments, and constitutions in a single online database.

Methodology

The Global Health and Human Rights Database seeks to bring together three connected areas of human rights law for the public’s health, investigating the intersection of health and human rights by compiling, summarizing, and categorizing health-related human rights in judgments, international and regional instruments, and national constitutions.

Judgments section

The Global Health and Human Rights Database aims to provide comprehensive access to judgments at the intersection of health and human rights, categorized on the basis of the human rights claimed, the health topics advanced, and the geographic region concerned.

Following an exhaustive search for judgments in multiple languages—identified through academic scholarship, NGO announcements, international organizations, partner institutions, and online electronic databases—relevant judgments (largely under common law legal systems, but with examples from civil law systems) were selected for inclusion in the Database and summarized where the specific case:

1) is adjudicated by an international, regional, or domestic court (or quasi-judicial body, such as the UN Human Rights Committee and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights);

2) implicates a specified health topic; and

3) argues a right of individuals or groups or an obligation of duty-bearers referenced in relevant international or national law.

The researchers developed these qualifications through an iterative decision-making process, by which an initial set of proposed criteria was revised based upon expert feedback and refined based upon compiled judgments, with each case honing the initial criteria and formulating more specific criteria for future consideration.33 In classifying these selected judgments, the judgments section of the database was categorized principally through the rights claimed (grouped under clusters of freedoms, entitlements, and underlying determinants developed in General Comment 14) and the health topics advanced (based on WHO classifications), revising these categories to arrive at the rights and health topics outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Rights and health topics categories

| Rights | Health Topics |

| Right to healthRight to lifeRight to bodily integrity

Right to liberty and security of person Right to water Right to food Right to property Right to social security Right to work Right to the enjoyment of favorable working conditions Right to privacy Right to due process Right to education Right to housing Right to family life Right to enjoyment of the benefits of culture Right to participation Right to development Right to clean environment Right to identity Freedom of association Freedom of expression Freedom of movement and residence Freedom of religion Freedom from torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment Right of access to information Freedom from discrimination |

Adolescent health (e.g, ages 10-19: depression stemming from hostile social environment, violence, sexually transmitted infections, adolescent diabetes, adolescent nutrition)Health services (e.g., health care, equipment, staff, information, access to medicines)Health promotion (e.g., education, community development, policy, legislation, regulation)Infectious diseases (e.g., HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, tropical diseases)Chronic diseases (e.g., cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, respiratory tract diseases)Child health and development (e.g., child abuse, custody)Aging (e.g., nursing facility care, age discrimination)Environmental health (e.g., drinking water, sanitation, food safety, environmental pollution, air pollution, climate change, social environment)Emergencies (e.g., armed conflicts, disasters, disease outbreaks, bioterrorism)Health technology and pharmaceutical products (e.g., essential medicines, biomedical technologies, medical devices, research, drug resistance, ehealth)Health systems (e.g., health financing, health services, health education, medical education, health workforce, health legislation, health policies, social security, research, research policy)Clinical trials (e.g., vulnerable population, case control, ethics, informed consent)

Poverty (e.g., economic determinants of health) Gender (e.g., gender-based violence, sex/gender discrimination) Violence (e.g., war, child soldiers, post-war conditions) Population groups (e.g., children, women, older persons, indigenous populations, persons with disabilities, migrants, prisoners, refugees) Reproductive and sexual health (e.g., family planning, infertility, pregnancy, maternal health, breastfeeding, sexuality, sexually transmitted infections, female genital mutilation) Tobacco/Substance abuse (e.g., prevention and treatment of addiction) Mental health (e.g., treatment, institutionalization) Occupational health (e.g., workplace safety) |

In revising these categories, the researchers sought to reflect the rights claimed and health topics advanced in a significant number of relevant judgments. For example, given the vast array of health topics available, with many topics representing distal determinants of health, the researchers found it feasible and appropriate to delineate determinants as health topics only where they were proximal to health outcomes. Further, the set of health topics was not seen as fixed; rather, the categorization of health topics evolved as judgments were analyzed, entered into the Database, and reviewed by the researchers. Where experience showed that certain health issues were represented in a significant number of judgments through periodic review, the researchers have delineated these issues as a distinct health topic, as seen where a health topic was added based upon “population groups” to capture an expanding number of cases involving marginalized populations.

By arranging national, regional, and international jurisprudence in accordance with these categories, including judgments in more than one category where circumstances warrant, this Database endeavors to provide a comprehensive picture of rights-based litigation for health. After the initial identification and categorization of relevant judgments, the researchers summarized each judgment on the basis of the parties, arguments, judicial reasoning, holding, and outcome. Once summarized, these judgments were described on the basis of instrumental criteria—year, country, court, human rights, health topics, facts, decision, excerpts, and online link—incorporated into the database development software FileMaker Pro, and posted to the Database’s online interface.

International and regional instruments section

Complementing this rights-based jurisprudence, the Global Health and Human Rights Database seeks to compile international and regional legal instruments that codify the health-related rights identified in General Comment 14.

International and regional legal instruments were selected for inclusion in the Database and excerpted where the instrument:

1) is binding under international health law or is non-binding but reflects global health policy (the latter referred to as “soft law”); and

2) contains provisions that address a health-related right of individuals or groups or an obligation of duty-bearers.

Following initial identification, the researchers excerpted relevant provisions, and each instrument was described on the basis of a number of instrumental criteria—year of adoption, year of entry into force, legal status (legally binding or non-legally binding), regional scope, excerpts, and online link—incorporated into the database development software FileMaker Pro, and posted to the Database’s online interface.

National constitutions section

Given the growing “constitutionalization” of health-related rights and the role of constitutions in the national codification of human rights, the Global Health and Human Rights Database seeks to highlight constitutional provisions that uphold health-related rights, including those constitutions that draw upon referenced international and regional instruments.

Constitutions were selected for inclusion in the Database and excerpted where a constitutional provision:

1) addresses a right or an obligation explicitly linked with or interpreted in relation to health services or underlying determinants of health; and

2) explicitly declares either a right of individuals or groups or an obligation of duty-bearers (including provisions on freedoms, such as freedom from torture, which may be stated as a prohibition).

Focusing on actionable constitutional provisions, national constitutions were not included where they provide only a statement of aspiration, a cursory reference to a relevant health issue, or a broad definition of the government’s scope of work without an explicit declaration of government obligation or individual rights. Following initial identification, the researchers excerpted relevant provisions, and each constitution was described on the basis of a number of instrumental criteria—regional scope, year of adoption, year of enactment, original language, human rights, excerpts, and online link—incorporated into the database development software FileMaker Pro, and posted to the Database’s online interface.

Expert review and official launch of Database

To assure comprehensiveness in its scope and accuracy in its content, 52 public health and human rights scholars and practitioners (across geographic regions and health specialties) reviewed an initial model of the Database, using an online evaluative survey to elicit feedback on its usability and substance. In assessing its usability, reviewers were asked to evaluate the Database based on the interface of the website and the ease with which they were able to search and find a pre-selected judgment, international or regional instrument, or national constitution using the various search categories provided on the search page. This approach allowed the reviewer to confirm the appropriateness of the search categories, as well as suggest categories that should be added. Where the reviewer was unable to find the judgment, international or regional instrument, or national constitution through the search function, the reviewer was invited to identify the judgment or legal instrument for its inclusion. In confirming the substance of the Database, reviewers were also asked to assess the categorization of human rights and health topics in the judgments section of the Database and to evaluate the comprehensiveness, organization, and quality of the summaries across all three sections of the Database. Finally, reviewers were asked a series of conceptual questions on the overall ability of the Database to capture the dynamic interaction between health and human rights through its collection and categorization of judgments, international and regional instruments, and national constitutions. The researchers thereafter delineated additional categories, revised case summaries, and added new sources in accordance with this review, launching the Database publicly in the summer of 2012.

Results

Through its online interface, users can search the Global Health and Human Rights Database under each of its three independent sections. In the judgments section, users can either use a specific keyword search or conduct an advanced search for cases by the human rights claimed (grouped under clusters of freedoms and entitlements), the health topics advanced (based on WHO classifications), or the geographic region concerned (organized by UN region). In a similar manner, the international and regional instruments and the national constitutions sections allow users to search for instruments or constitutions based on their regional scope or through a keyword search. An interactive (Flash) global map feature, in Figure 1, allows country-specific searches for both judgments and constitutional provisions.

Figure 1. Search page of the Global Health and Human Rights Database

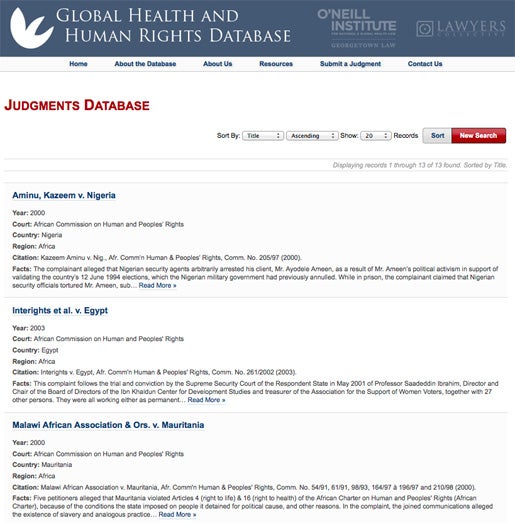

In viewing search results in each of the three sections of the Database, shown for the judgments section in Figure 2, users can sort results based upon several pertinent categories identified through the expert review:

- Judgments section – sorted by title, country, region, or year.

- International and regional instruments section – sorted by title, region, legal status, year of adoption, or year of entry into force.

- National constitutions section – sorted by country, region, year of adoption, or year of enactment.

Figure 2. Judgments search results

By selecting a specific result, as exemplified for a specific judgment in Figure 3, users can examine summaries of each judgment, international or regional instrument, and constitution. Supporting research beyond the categorizations and detailed summaries, the Database includes an online link to each judgment, international or regional instrument, and national constitution, enabling users to access the full text of the original source (in its original language and, where applicable, translated into English).

Figure 3. Judgments result page

The judgments section of the Database now houses summaries of over 350 cases, arising from a wide range of country contexts, health topics, and rights claims. While this non-empirical survey does not claim to represent the field completely, and the total number of judgments may well exceed those currently compiled (including those that did not result in written decisions), the selection methodology and expert review provide assurance that the Database encompasses the full scope of case law at the intersection of health and human rights. Throughout the development of the Database, the Lawyers Collective and the O’Neill Institute have established an extensive network of partners around the world who have assisted in identifying, summarizing, and translating cases. These partners will allow for the inclusion of judgments issued not only from the highest national court, but also from lower courts, providing a more comprehensive understanding of health-related rights litigation. Through these ongoing relationships, the Database will remain current in compiling and categorizing developments in relevant judgments and legal instruments at the domestic, regional, and international levels. As the Database continues to evolve, users will have the opportunity to submit additional judgments, international or regional instruments, and national constitutions where specific legal sources are not yet included, with an online form allowing for the attachment of the original source and user-initiated categorization. Continuous updating of the Database through user communications and periodic evaluations, along with the participation of global networks at the intersection of health and human rights, will assure the Database’s ongoing legitimacy and relevance in a rapidly changing human rights landscape.

Analysis

By summarizing judgments, international and regional instruments, and national constitutions and categorizing these summaries in the searchable Global Health and Human Rights Database, this systematic legal survey catalogues the interaction between health and human rights at national, regional, and international levels. Despite national progress in creating accountability structures for health-related rights, efforts have only begun to assess the reasoning, content, and effect of legal claims pursuant to these human rights standards. As litigation has increased, rising alongside a burgeoning accountability movement at the intersection of health and human rights, both proponents and opponents of rights-based policy have begun to question the limits of this enforcement strategy for national policy and the impact of this litigation on global health. Given this growing critique of human rights implementation—leading to criticisms of public interest litigation, questions of legal legitimacy, and claims of “judicial activism”—there arises an imperative for interdisciplinary analysis: examining these precedents for rights-based claims, comparing divergent legal strategies conducive to the realization of human rights, and assessing the effects of law reforms on the public’s health. Meeting this imperative, the Global Health and Human Rights Database provides the academic and practice community with a research base to identify transnational precedents from relevant legal judgments (facilitating policy reforms), enable comparative analysis of human rights jurisprudence (supporting legal and social scientific studies), and frame empirical scholarship on the role of human rights as a determinant of the public’s health (clarifying the impact of health-related rights on public health outcomes).

Transnational precedent

Serving as illustration and inspiration, successful rights-based claims can lead to the translation of compelling jurisprudential reasoning across national contexts. While legal reasoning is not considered to be binding precedent across nations, it has long been recognized that both regional and national judgments have persuasive authority outside their jurisdictions.34,35 Domestic courts have repeatedly analyzed foreign legal decisions, often from multiple jurisdictions, when developing the contours of constitutional obligations for the protection of health. For example, the Constitutional Court of South Africa has considered cases from the United States Supreme Court, the German Federal Constitutional Court, the Supreme Court of Canada, and the United Kingdom House of Lords when determining remedies for health-related violations pursuant to the Constitution of South Africa.36 Compounding these direct effects, such judgments have indirect effects in raising global health awareness, catalyzing transnational movements, and spurring additional rights-based claims.17 In the context of health-related human rights claims, scholars have begun to identify the claims most likely to find jurisprudential success, adding some measure of consistency across countries and claims.37 Through similarities in reasoning, judicial bodies can examine analogous factual situations and governmental responses, with norms emerging and cascading across jurisdictions and through supranational forums.38,39 Given the categorization under this Database, it is expected that as advocates and practitioners engage in comparative analyses of legal strategies, legal reasoning across national contexts may serve as precedent for future judgments, reinforcing universality in the core content of rights, facilitating harmonization where comparable circumstances warrant, and appreciating difference in national approaches to rights realization.

Comparative analysis

While recognizing a sweeping imperative for universal and enforceable human rights standards under international law, context matters in the realization of rights, as both the capabilities of the rights-holder and the policies of the duty-bearer depend upon a range of distinct factors. Specific political environments appear more conducive to rights-based claims, and among those environments, it is clear that only a portion of cases are responsive to treaty-based legal argumentation.40 Taken to the extreme, this Database highlights entire country contexts in which there is scant evidence of any human rights jurisprudence for health. Even in those countries where there is comparable legal mobilization, it becomes apparent that different states will achieve different levels of rights realization at different times, with comparative institutional analysis necessary to examine the differential individual entitlements and differential adjudicatory procedures by which these cases are decided and implemented.20 For example, given distinctions inherent in the principle of progressive realization, leaving state realization of rights dependent, inter alia, on national resources and international assistance and cooperation, it is useful to compare the health systems of states at equivalent levels of development—ensuring consistency in resource-dependent claims across comparable countries and comporting with General Comment 14’s admonition that states bear “a specific and continuing obligation to move as expeditiously and effectively as possible towards […] full realisation.”12,8 Through such comparative analysis of the dynamics of litigation, moving beyond the emblematic case studies often cited in jurisprudential analysis, a deeper understanding of human rights realization can be found in explicating divergent jurisprudential approaches to achieving the same rights-based goals. With the Database identifying commonalities across judgments, such categorized information lays the groundwork for more robust social scientific analysis to assess underlying social, political, and economic determinants of litigation.

Empirical scholarship

With the effects of such litigation largely unexamined, there is a pressing research need for the health and human rights community to clarify the connections between human rights litigation and public health promotion. Outside of legal success before a judicial body, it is necessary to research: the mechanisms by which international and regional instruments, national constitutions, and judgments are implemented through policies; the obstacles that impede implementation of rights-based policy reforms; and the pathways through which such implementation can be conducive to meeting basic health needs.41 In recent years, scholars have argued that human rights litigation for health, especially when extended beyond the response to HIV/AIDS, may serve to entrench privilege through medical care, undercut principles of distributive justice, and abandon those in greatest need.42,43,44,45 To some outside the human rights practice community, these potential distortions in national health governance are seen as fatal flaws of justiciability and cause for casting aside human rights in health policy.46 Yet even as this litigation agenda faces opposition, too little remains known about the multivalent effects of these judgments on the public’s health, including the policies impacted, the populations affected, and the outcomes achieved.47 Given the potential of these criticisms to undermine accountability for social change, it is vital that human rights scholars examine the empirical, as well as normative, justifications for health-related rights.48 With a clear trend toward an expansion of litigation opportunities, as individuals and NGOs seek to hold governments accountable for human rights obligations, limited data are available to facilitate empirical understanding of the causal link between these international instruments, rights-based judgments, health policies, and public health outcomes.29 Examining these social and political processes through the growth of this Database, it is expected that such a resource may provide the basis for empirical research on the impact of health-related rights on the public’s health.

Conclusion

Human rights law is playing an increasingly influential role in national health policy, with human rights jurisprudence giving meaning to the content of international and regional instruments and national constitutions. With this human rights litigation landscape in a constant state of evolution, the Global Health and Human Rights Database will allow advocates, practitioners, and scholars to stay apprised of these changes. As the O’Neill Institute, WHO, and Lawyers Collective work together to disseminate this Global Health and Human Rights Database, it will be necessary to compile and categorize the continuing expansion of judgments and related legal instruments, ensuring that these legal developments are available to the world.

Acknowledgments

In the four-year development of the Global Health and Human Rights Database, the researchers are grateful for the insightful contributions of a series of research assistants, the global resources of human rights staff across the United Nations, and the thoughtful commentary of expert reviewers, each of whom is acknowledged in the online Database. Additionally, the researchers would like to acknowledge specifically John Richards and Tim King for their long-standing work on the Database design and development. Linda D. and Timothy J. O’Neill Professor of Global Health Law at Georgetown University.

Benjamin Mason Meier, JD, LLM, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Global Health Policy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a Scholar at the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law.

Oscar A. Cabrera, Abogado, LLM, is the Director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law and Visiting Professor of Law at Georgetown University.

Ana Ayala, JD, LLM, is a Law Fellow at the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law.

Lawrence O. Gostin, JD, LLD (Hon.), is the Faculty Director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law and the Linda D. and Timothy J. O’Neill Professor of Global Health Law at Georgetown University.

Please address correspondence to the authors at bmeier@unc.edu.

References

1. World Health Organization, O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, and Lawyers Collective, Global Health and Human Rights Database. Available Summer 2012 at http://www.ghhrdb.org.

2. L. O. Gostin, E. A. Friedman, G. Ooms et al. “The joint action and learning initiative: towards a global agreement on national and global responsibilities for health,” PLoS Medicine 8/5 (2011), pp. 1-5. Available at http://www.plosmedicine.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.1001031.

3. L. Gostin and J. M. Mann, “Towards the development of a human rights impact assessment for the formulation and evaluation of public health policies,” Health and Human Rights: An International Journal 1 (1994), pp. 58-80.

4. Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization (1948).

5. M. Robinson, “What rights can add to good development practice,” in P. Alston and M. Robinson (eds), Human Rights and Development: Towards Mutual Enforcement (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 25-43.

6. A. E. Yamin, “Beyond compassion: The central role of accountability in applying a human rights framework to health,” Health and Human Rights: An International Journal 10/2 (2008), pp. 1-20

7. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI), 993 (1966). Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/cescr.htm.

8. B. Toebes, The Right to Health as a Human Right in International Law (Antwerpen, Groningen, Oxford: Intersentia/Hart, 1999).

9. B. M. Meier, “Global health governance and the contentious politics of human rights: Mainstreaming the right to health for public health advancement,” Stanford Journal of International Law 46 (2010), pp. 1-50.

10. L. London, “What is a human rights-based approach to health and does it matter?” Health and Human Rights: An International Journal 10 (2008), pp. 65-80.

11. United Nations, World Conference on Human Rights: Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, Vienna, June 14-25, 1993.

12. UN Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, The Substantive Issues Arising in the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, UN Doc. No. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000).

13. B. Simmons, Mobilizing for Human Rights: International Law in Domestic Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

14. E. Kinney and B. Clark, “Provisions for health and health care in the constitutions of the countries of the world,” Cornell International Law Journal 37 (2004), pp. 285-355.

15. G. Backman, P. Hunt, R. Khosla et al, “Health systems and the right to health: An assessment of 194 countries,” Lancet 372 (2008), pp. 2047-2085.

16. A. E. Yamin and S. Gloppen (eds), Litigating Health Rights: Can Courts Bring More Justice to Health? (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011).

17. M. Langford, “Justiciability of social rights: From practice to theory,” in Social Rights Jurisprudence: Emerging Trends in International and Comparative Law (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008), pp. 1-45.

18. H. J. Steiner, P. Alston, and R. Goodman, International Human Rights in Context: Law, Politics, Morals (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

19. I. Byrne, “Enforcing the right to health: Innovative lessons from domestic courts,” in A. Clapham and M. Robinson (eds), Realizing the Right to Health (Zurich: Rüffer & Rub, 2009).

20. M. Langford, “Domestic adjudication of economic, social and cultural rights: A socio-legal survey,” SUR – International Journal of Human Rights 11 (2010).

21. C. Courtis, Courts and Legal Enforcement of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Comparative Experiences of Justiciability (Geneva: International Commission of Jurists, 2008).

22. See, for example, A.E. Yamin, O. Parra-Vera, and C. Gianella, “Colombia – Judicial protection of the right to health: An elusive promise?” in Litigating Health Rights: Can Courts Bring More Justice to Health? (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011).

23. L. O. Gostin, The AIDS Pandemic: Complacency, Injustice and Unfulfilled Expectations (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004).

24. S. Gruskin, E. J. Mills, and D. Tarantola, “History, principles, and practice of health and human rights,” Lancet 370 (2007), pp. 449-455.

25. B. M. Meier and A. E. Yamin, “Right to health litigation and HIV/AIDS policy,” Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 39, Supplement 1 (2011), pp. 81-84.

26. L. Gable, “The proliferation of human rights in global health governance,” Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 35/4 (2007), pp. 534-544.

27. S. Gloppen and M.J. Roseman, “Introduction: Can litigation bring justice to health?” in Litigating Health Rights: Can Courts Bring More Justice to Health? (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011).

28. A. E. Yamin, “The future in the mirror: Incorporating strategies for the defense and promotion of economic, social and cultural rights into the mainstream human rights agenda,” Human Rights Quarterly 27 (2005), pp. 1200-1244.

29. Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, G. A. Res. A/RES/63/117 (2008). Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cescr/docs/A-RES-63-117.pdf.

30. V. Gauri and D. M. Brinks (eds), Courting Social Justice: Judicial Enforcement of Social and Economic Rights in the Developing World (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

31. World Health Organization, Health and Human Rights Activities Within WHO (2005).

32. World Health Organization, Health and Human Rights: Databases (2007). Available at http://www.who.int/hhr/databases/en/.

33. J. Merrill, J. Keeling, and K. Gebbie, “Toward standardized, comparable public health systems data: A taxonomic description of essential public health work,” Health Services Research 44 (2009), pp. 1818-1841.

34. H. Lauterpacht, International Law and Human Rights (New York: F. A. Praeger, 1950).

35. T. H. Bingham, Widening Horizons: The Influence of Comparative Law and International Law on Domestic Law (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

36. L. Forman, “What future for the minimum core? Contextualizing the implications of South African socioeconomic rights jurisprudence for the international human right to health,” in Global Health and Human Rights: Legal and Philosophical Perspectives (London: Routledge, 2009).

37. H. V. Hogerzeil, “Essential medicines and human rights: What can they learn from each other?” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 84 (2006), pp. 1-5.

38. K. Sikkink, “Transnational politics, international relations theory, and human rights,” Political Science & Politics 31/3 (1998), pp. 516-523.

39. M. Finnemore, “Are legal norms distinctive?” International Law and Politics 32/3 (2000), pp. 699-706.

40. J. Donnelly, “Human rights and Asian values: A defense of ‘Western universalism,'” in The East Asian Challenge for Human Rights (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

41. S. Gloppen, “Legal enforcement of social rights: Enabling conditions and impact assessment,” Erasmus Law Review 2 (2009), pp. 465-480.

42. D. Barak-Erez and A. Gross (eds), Exploring Social Rights: Between Theory and Practice (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2007).

43. O.L.M. Ferraz, “The right to health in the courts of Brazil: Worsening health inequities?” Health and Human Rights: An International Journal 11 (2009), pp. 33-45.

44. L. Bernier, “International socioeconomic human rights: The key to global health improvement,” International Journal of Human Rights 14 (2010), pp. 246-279.

45. But see J. Biehl, J.J. Amon, M.P. Socal, and A. Petryna, “Between the court and the clinic: Lawsuits for medicines and the right to health in Brazil,” Health and Human Rights: An International Journal 14/1 (2012).

46. W. Easterly, “Human rights are the wrong basis for healthcare,” Financial Times (Oct. 12, 2009).

47. S. Gloppen, “Litigation as a strategy to hold governments accountable for implementing the right to health,” Health and Human Rights: An International Journal 10 (2008), pp. 21-36.

48. V. Gauri and D.M. Brinks (eds), Courting Social Justice: Judicial Enforcement of Social and Economic Rights in the Developing World (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008).