Public Reporting on Solitary Confinement in Australian and New Zealand Prisons and Youth Detention Facilities

PERSPECTIVE Vol 27/1, 2025, pp. 19-26 PDF

James Foulds, Sharon Shalev, Erik Monasterio, Alex Campbell, Rebecca R. Shuttleworth, and Stuart A. Kinner

Introduction

Recent national inquiries in Australia and New Zealand describe historic failures in the treatment of people in government-run institutions, including the routine use of restrictive and traumatizing practices.[1] However, restrictive practices such as solitary confinement remain widespread in prisons and youth detention facilities, despite their known harms to physical and mental health and their potential to infringe human rights.[2] The use of solitary confinement on children, Indigenous People, and those living with a disability (for example, a learning disability or serious mental illness) is of particular concern and is likely to violate international human rights conventions.[3]

To avoid repeating past mistakes, it is imperative that restrictive practices in custodial settings be transparently reported and subject to public scrutiny.[4] Although solitary confinement is a health and human rights issue of global importance, in this essay we take a regional perspective by examining the extent to which there is regular and transparent reporting on solitary confinement in Australian and New Zealand prisons and youth detention centers.

Defining solitary confinement

Solitary confinement is used for many reasons in carceral settings, including to manage the risk of violence (either by or toward the person who is subjected to solitary confinement), to contain infectious disease outbreaks, and to manage severe behavioral disturbance. According to the United Nations (UN) Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisons (the Mandela Rules), solitary confinement is the confinement of prisoners for 22 hours or more per day without meaningful human contact.[5] While any duration of solitary confinement may be harmful, prolonged solitary confinement lasting over 15 consecutive days is more likely to cause profound and irreversible physical and psychological harm.[6]

Worldwide, many different official reporting terms are used for restrictive practices that may or may not involve solitary confinement. In Australia and New Zealand, common terms include segregation, separation, isolation, lockdown, confinement, secure care, and special care.[7] Seclusion is used in mental health settings, where it has a more consistent definition and is routinely monitored and reported.[8]

In Australia, national correctional guidelines define “separation and segregation” as the “separate confinement of a prisoner … for the protection and safety of others where there is no other reasonable way to manage the risk/s to safety, security, or good order and discipline of the correctional centre.”[9] This definition sometimes conflicts with other jurisdiction-specific guidelines. For example, in the New South Wales Youth Justice procedures, separation can also to refer to keeping groups of young people—rather than individuals—apart.[10] In New Zealand, the Corrections Act of 2004 defines segregation as “the opportunity of a prisoner to associate with other prisoners [being] restricted or denied.”[11]

In youth detention settings, the term isolation is commonly used. For example, in the Victorian Youth Justice Act of 2024, isolation means “the placement of a child or young person in a locked room or other contained area—(a) separated from other children and young persons held in custody in the youth justice custodial centre; and (b) separated from the normal routine of the youth justice custodial centre.”[12] The act adds that isolation is not occurring if the young person is “participating in, or has the opportunity to participate in, the normal routine of the youth justice custodial centre but separate from other children and young persons.” In the Australian Capital Territory, isolation is defined as “the physical confinement of a child or young person on their own for a notable period of time, e.g. greater than 10 minutes.”[13] In some Australian jurisdictions—for example, Western Australia—the term confinement equates to segregation as a form of punishment.[14] Finally, lockdown has no official definition but is commonly used to refer to an institutional response whereby a group of people within an institution have their movements restricted, usually in response to an internal threat such as a violent incident or staff shortages.

These overlapping, ambiguous, and inconsistent definitions of practices that may or may not equate to solitary confinement make monitoring difficult.

International human rights frameworks

Many UN instruments and bodies mention solitary confinement. These include international treaties such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, as well as reports by the UN Special Rapporteur on torture and the UN Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. Perhaps the most widely cited UN source on solitary confinement is the Mandela Rules, which define solitary confinement and assert that it should occur “only in exceptional cases as a last resort, for as short a time as possible and subject to independent review.”[15]

The Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT), adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2002, provides for the establishment of national preventive mechanisms to monitor places of deprivation of liberty, including restrictive practices such as solitary confinement.[16] New Zealand ratified OPCAT in 2007. Five independent agencies, including the Ombudsman, monitor and report on OPCAT compliance in New Zealand. In 2013, the UN Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture visited New Zealand and reported its findings, including on the use of solitary confinement and other restrictive practices.[17] Australia ratified OPCAT in 2017. Inspection mechanisms are coordinated by the Commonwealth Ombudsman and involve ombudsman’s offices for the commonwealth and each state and territory, in addition to several other bodies. However, national preventive mechanisms are not yet active in all Australian jurisdictions. Furthermore, in 2023 the UN Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture suspended (and later terminated) an inspection visit to Australia because of obstacles to carrying out its mandate.[18] The inspection team encountered “a discourteous, and in some cases hostile, reception,” incorrect information, and the inability to access certain places of detention in Queensland and New South Wales.[19] This indicates that Australia is not yet compliant with its OPCAT obligations.

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is also relevant to this issue, considering the overrepresentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People and Māori in prisons and youth detention facilities in Australia and New Zealand, many of whom are also living with a disability.[20] The disproportionate exposure of Indigenous People to solitary confinement perpetuates the intergenerational trauma and human rights abuses of centuries of colonization. People with a disability, including serious mental illness, are also likely to experience solitary confinement when they are imprisoned.[21] This is in contravention of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the Mandela Rules, the latter of which states that “the imposition of solitary confinement should be prohibited in the case of prisoners with mental or physical disabilities when their conditions would be exacerbated by such measures.”[22]

Reporting on solitary confinement in custodial facilities in Australia and New Zealand

We aimed to identify reporting mechanisms that provide regular data on solitary confinement (or its equivalent terms) in prisons and youth detention facilities, similar to the publicly available data on seclusion in psychiatric facilities.[23] To do this, we searched the websites of prison and youth justice monitoring authorities in Australian and New Zealand jurisdictions and then directly contacted those authorities to ensure that we had not missed any major sources of information.

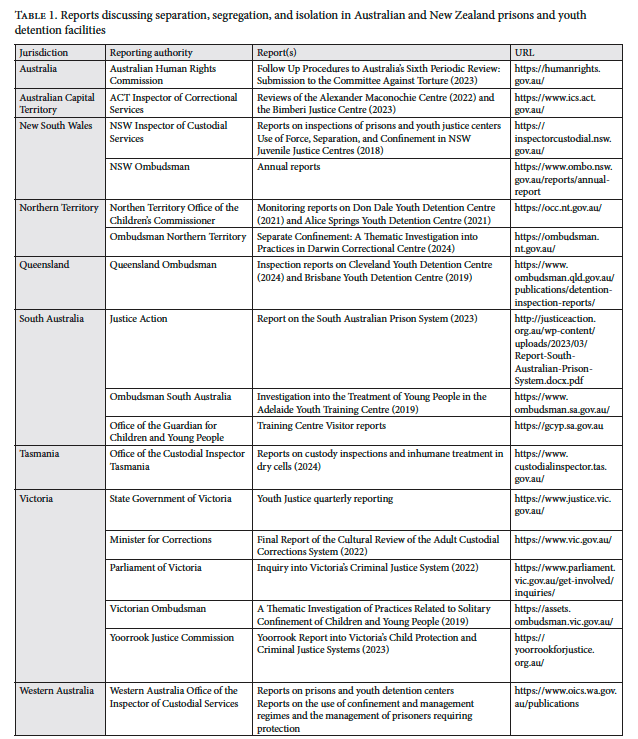

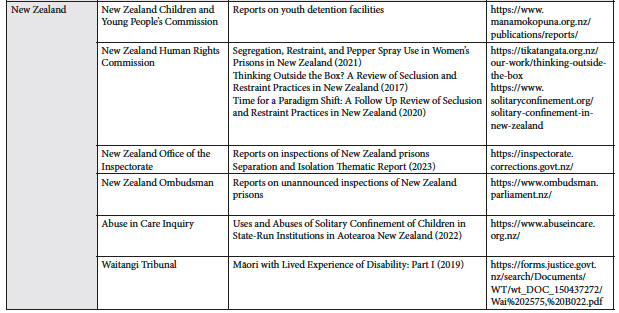

We identified relevant reports from all jurisdictions in Australia and New Zealand (Table 1). However, the information that these reports provided on solitary confinement was variable and often ambiguous. Even when the reports provided quantitative data on restrictive practices, in most cases it was difficult to know whether these practices amounted to solitary confinement. Most reports gave limited detail on the incidence, duration, and reasons for solitary confinement, and the demographic profile of the people exposed to it. Several reports commented on the difficulty the investigation team had experienced when accessing data on restrictive practices. For example, an investigation of the Darwin Correctional Centre by the Northern Territory Ombudsman found inconsistent reporting of the time spent out of cells for people subject to separate confinement.[24]

Several reports commented on the impact of staff shortages on restrictive practices. For example, a report by the New Zealand Ombudsman covering an eight-day period in early 2020 found that most prisoners in two units at a maximum-security prison spent 22–23 hours per day in their cell and were therefore subject to solitary confinement.[25] This practice was influenced by staff shortages.[26] Similar issues related to staff shortages were noted in reports from Western Australia and Queensland. [27]

We found jurisdiction-wide quantitative data on restrictive practices from several jurisdictions, including Victoria, New South Wales, Tasmania, Western Australia, and New Zealand.[28] Interpretation of the data required some understanding of the definitions used in each of those jurisdictions, but in many cases, this at least provided a benchmark to show how those practices were tracking over time and, in some cases, between facilities.

The Australian Productivity Commission publicly reports national benchmark data on the average time spent out of cells by people in prison, although it does not yet have a comparable indicator for children in youth detention.[29] Data on time out of prison cells are also reported by some individual jurisdictions, such as Tasmania.[30] In New Zealand, benchmark data on time spent out of cells are tracked internally by the Department of Corrections, and nationwide data on segregation and separation have been published by the Department of Corrections Office of the Inspectorate.[31] Data on time out of cells are valuable but uninformative with regard to solitary confinement. Nonetheless, the existence of these data suggests that it may be possible to collect and report data on instances where the time out of cells is less than two hours per day, or where there was no meaningful human contact during that time (rule 44 of the Mandela Rules).

Children in solitary confinement

Although any person may be harmed by solitary confinement, children are at particular risk because of their developmental immaturity and lesser capacity to advocate for their own rights. The UN Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of Their Liberty, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1990, state that “closed or solitary confinement or any other punishment that may compromise the physical or mental health of the juvenile concerned” is “strictly prohibited.”[32] Despite recent inquiries and the well-acknowledged harms of subjecting (typically vulnerable and traumatized) children to solitary confinement, the Australian Human Rights Commission remains “seriously concerned” about the use of solitary confinement in Australian youth detention facilities.[33] Similar comments have been made in New Zealand, and the comments are echoed in many of the inspection reports listed in Table 1.

As shown in Table 1, we found statewide data on restrictive practices in youth justice facilities from New South Wales and Victoria. Victoria provides regular quarterly reporting on the number of isolation episodes for children in youth justice facilities. These figures are broken down into behavioral-based isolation and isolations based on concerns for the security of the center. They provide no detail about the age, sex, or ethnicity of the children exposed to isolation, or the duration of episodes. For most other jurisdictions, reporting appears to be less consistent, and it relies on ad hoc inspections of individual carceral facilities. Most of these inspection reports provide little quantitative data, with several reports commenting that this was because the data were not accurately recorded by the justice authority. The impact of staff shortages was mentioned in several reports. For example, a 2024 report on a Queensland youth justice facility housing mostly Aboriginal young people found that staff shortages contributed to high levels of separation.[34]

In New Zealand, the use of solitary confinement in institutions that house young people has come under scrutiny as a result of the recent Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care. An independent report for the commission, published in 2022, explores the history of solitary confinement practices in these settings, which include youth justice facilities. The report concludes that the use of solitary confinement is widespread, often punitive, and inconsistent with human right principles.[35] While some of the more “extreme practices” of past decades no longer occur, the report notes that “the use of ‘secure’ rooms and units for children persists and continues to be a source of grave concern.”[36]

Research and policy implications

Australia and New Zealand are high-income countries with high scores on indices of public trust and democracy.[37] And yet, recent major inquiries in both countries show that there have been decades of widespread human rights abuses involving people in state care, including children.[38] Numerous recent inspections of places of detention in Australia and New Zealand have shown that at least some of the abusive practices referred to in the inquiries are still happening in prisons and youth detention centers.

As signatories to OPCAT, Australia and New Zealand have adopted mechanisms for monitoring places of detention. However, there are still major gaps in routine reporting, in part because of ambiguous definitions and a lack of transparency involving restrictive practices that may or may not amount to solitary confinement. Regardless of definitions, the amount of time that people in Australian prisons spend out of cells is already routinely reported by the Productivity Commission; and in New Zealand, these data are routinely collected and reported internally by the Department of Corrections. This suggests that mandatory public reporting of all episodes in which a person spends less than two hours per day outside their cell would not be difficult, at least for adult custodial settings. We argue that to prevent further human rights violations such as those identified in recent inquiries, this reporting should be routine and mandatory for both prisons and youth detention facilities.

Mandatory reporting will require clear, universally agreed-upon definitions for key terms such as segregation, separation, confinement, and isolation. There must be fewer terms used to describe the same thing. Routine reporting on restrictive practices should include information about the person affected, including sex, age, ethnicity, and the presence of any physical, mental, or cognitive disability. It should also record the main reason for the restrictive intervention and its duration.

Research is needed to help develop better alternatives to solitary confinement. While this is not straightforward, there is already a large body of literature from the mental health sector on how to reduce restrictive practices.[39] Many of these practices could be adapted for use in custodial settings. The recent eradication of tie-down beds in New Zealand prisons shows that research-led changes in restrictive practices can be achieved on a national scale.[40] If Australia and New Zealand wish to avoid repeating the wrongs of the past, both countries must commit to protecting the rights of their most disadvantaged people, including those who are incarcerated.

James Foulds, PhD, is a forensic psychiatrist and associate professor in psychological medicine at the University of Otago, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Sharon Shalev, PhD, is a research associate at the Centre for Criminology, University of Oxford, United Kingdom.

Erik Monasterio, FRANZCP, is a forensic psychiatrist in private practice in Christchurch, New Zealand.

Alex Campbell, MPH, is a research assistant in the Justice Health Group, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia, and the Justice Health Group, School of Population Health, Curtin University, Perth, Australia.

Rebecca Shuttleworth, MPH, is a research assistant in the Justice Health Group, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia, and the Justice Health Group, School of Population Health, Curtin University, Perth, Australia.

Stuart Kinner, PhD, is a professor and head of the Justice Health Group, School of Population Health, Curtin University, Perth, Australia, and professor in the Justice Health Group, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia.

Please address correspondence to James Foulds. Email: james.foulds@otago.ac.nz.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2025 Foulds, Shalev, Monasterio, Campbell, Shuttleworth, and Kinner. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

[1] Commonwealth of Australia, Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability: Final Report (2023); Royal Commision of Inquiry (New Zealand), Whanaaketia: Abuse in Care Royal Commission of Inquiry (2024).

[2] C. Haney, “The Psychological Effects of Solitary Confinement: A Systematic Critique,” Crime and Justice 47 (2018); S. Shalev, “Solitary Confinement as a Prison Health Issue,” in S. Enggist, L. Moller, G. Galea, et al. (eds), WHO Guide to Prisons and Health (World Health Organization, 2017).

[3] Convention on the Rights of the Child, G.A. Res. 44/25 (1989); Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, G.A. Res. 61/106 (2006); United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, G.A. Res. 61/295 (2007).

[4] T. Lamusse, “Solitary Confinement in New Zealand Prisons,” Economic and Social Research Aotearoa 7 (2018).

[5] United Nations General Assembly, United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, UN Doc. A/RES/70/175 (2015).

[6] Ibid., rule 44; Haney (see note 2).

[7] Corrective Services Administrators’ Council (Australia), Guiding Principles for Corrections in Australia (2018); Department of Corrections Office of the Inspectorate (New Zealand), Separation and Isolation Thematic Report (2023).

[8] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Seclusion and Restraint Data (2024), https://www.aihw.gov.au/mental-health/topic-areas/seclusion-and-restraint.

[9] Corrective Services Administrators’ Council (see note 7).

[10] New South Wales Government (Australia), Youth Justice Separation Procedure (2024), https://www.nsw.gov.au/legal-and-justice/youth-justice/procedures/separation-procedure.

[11] New Zealand, Corrections Act (2004).

[12] Victoria, Australia, Youth Justice Act (2024).

[13] Inspector of Correctional Services (Australian Capital Territory), Isolation of Children and Young People at Bimberi Youth Justice Centre (2023).

[14] Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services (Western Australia), The Use of Confinement and Management Regimes (2022).

[15] United Nations General Assembly (2015, see note 5), rules 44–45.

[16] Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, G.A. Res. 57/199 (2002).

[17] Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture and Other Cruel Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Visit to New Zealand Undertaken from 29 April to 8 May 2013: Observations and Recommendations Addressed to the State Party, UN Doc. CAT/OP/NZL/1 (2017).

[18] A. Lachsz, “Why Has a UN Torture Prevention Subcommittee Suspended Its Visit to Australia?” (October 27, 2022), Conversation, https://theconversation.com/why-has-a-un-torture-prevention-subcommittee-suspended-its-visit-to-australia-193295.

[19] Ibid.

[20] United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (see note 3); Waitangi Tribunal (New Zealand), Māori with Lived Experience of Disability: Part I (2019).

[21] E. Monasterio, S. Every-Palmer, J. Norris, et al., “Mentally Ill People in Our Prisons Are Suffering Human Rights Violations,” New Zealand Medical Journal 133 (2020).

[22] Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (see note 3); United Nations General Assembly (2015, see note 5), rule 45(2).

[23] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (see note 8).

[24] Office of the Ombudsman (Northern Territory, Australia), Separate Confinement: A Thematic Investigation into Practices in Darwin Correctional Centre (2024).

[25] Office of the Ombudsman (New Zealand), Final Report on an Unannounced Inspection of Auckland Prison Under the Crimes of Torture Act 1989 (2020).

[26] Ibid.

[27] Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services (Western Australia), Inspection of the Intensive Support Unit at Banksia Detention Centre (2021); Inspector of Detention Services (Queensland, Australia), Cleveland Youth Detention Centre Inspection Report: Focus on Separation and Staff Shortages (2024).

[28] State Government of Victoria (Australia), Youth Justice Custodial Services Quarterly Category One Isolation Reporting (1 July to 30 September 2024) (2024); Government Inspector of Custodial Services (New South Wales, Australia), Use of Force, Separation, Segregation and Confinement in NSW Juvenile Justice Centres (2018); Office of the Custodial Inspector (Tasmania, Australia), Annual Report 2023–24 (2024); Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services (2022, see note 14); Department of Corrections Office of the Inspectorate (see note 7).

[29] Productivity Commission (Australia). Report on Government Services (2024) https://www.pc.gov.au/ongoing/report-on-government-services/2024/justice/corrective-services.

[30] Office of the Custodial Inspector (Tasmania, Australia) (see note 28).

[31] Department of Corrections Office of the Inspectorate (see note 7).

[32] United Nations General Assembly, United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of Their Liberty, UN Doc. A/RES/45/113 (1990).

[33] Australian Human Rights Commission, Follow Up Procedures to Australia’s Sixth Periodic Review: Submission to the Committee Against Torture (2023).

[34] Inspector of Detention Services (see note 27).

[35] S. Shalev, Uses and Abuses of Solitary Confinement of Children in State-Run Institutions in Aotearoa New Zealand (2022).

[36] Ibid., p. 28.

[37] Economist Intelligence Unit, “Democracy Index 2024,” https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2024/.

[38] Commonwealth of Australia (see note 1); and Royal Commission of Inquiry (see note 1).

[39] J. Fletcher, B. Hamilton, S Kinner, et al., “Working Towards Least Restrictive Environments in Acute Mental Health Wards in the Context of Locked Door Policy and Practice,” International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 28/2 (2019).

[40] J. Carr and P. King, “The Use of ‘Tie Down’ in New Zealand Prisons—What Is the Role of the Health Sector?,” New Zealand Medical Journal 132/1493 (2019).