Eleanor Emery, Carmen Stellar, Krista Dubin, Taryn Clark, Aynsley Duncan, Alejandro Lopez, Joanne Ahola, Terri Edersheim, and Nicole Sirotin

Introduction

Every year, thousands of people seek legal asylum in the United States after fleeing persecution in their home countries. In 2014, approximately 121,200 asylum applications were filed in the US, representing a 44% increase from 2013.1 It has been estimated that there are over 400,000 foreign-born torture survivors living in the US, of which a large proportion reside in the New York metropolitan area.2 In 2012, asylum applications filed in New York City and Newark, New Jersey, accounted for nearly one third of all US asylum receipts registered in that year.3

Many of the individuals seeking asylum have been subjected to various forms of torture and maltreatment, resulting in physical and psychological scars. Careful history-taking and physical examination can reveal evidence of torture and maltreatment, including symptoms of psychiatric disorders, neurological deficits, and physical scars.4 Healthcare professionals can play a crucial role in the asylum process by conducting clinical evaluations and generating medical affidavits that document these findings. Although only 37.5% of asylum seekers overall are granted asylum in the US, 89% of those with supporting medical affidavits are granted asylum.5 Therefore, medical professionals are important expert witnesses in these legal procedures.

The recent surge in adults and unaccompanied minors crossing the southern border has resulted in a crisis for US immigration courts. The federal immigration court system had nearly half a million active cases pending at the end of July 2015, and “non-priority” immigration cases can expect delays in processing of up to five years.6 Although not all immigrants—or even all victims of human rights abuses—apply for legal asylum, the recent increase in immigration has resulted in a concomitant increase in the number of active asylum cases in the US.7 The demand for forensic evaluations of asylum seekers is far greater than the supply of clinicians trained to provide these services. In the summer of 2015, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) placed a temporary hold on accepting new cases while it worked through an unprecedented backlog of pending requests.

Despite the demonstrated need, medical schools rarely address issues of torture, forensic documentation, or the intersection of health and human rights in their formal curricula. In the US, doctors typically have three levels of training—undergraduate studies, medical school, and residency—before they are qualified as attending-level physicians. It is usually at medical school that students become interested in their future specialties, which makes the content of curricular programming especially important at this time.

Despite rising national and international awareness of the relationship between health and human rights, only 14% of US medical schools offer required or elective courses in this field.8 Moreover, very few residency programs provide training in this area, and there is no national or standardized recruitment or training program for attending-level physicians.9 US physicians who want experience in human rights work generally seek out training and volunteer opportunities at nongovernmental organizations such as PHR. Some doctors conduct forensic evaluations as part of human rights clinics associated with teaching hospitals. These clinics provide a context in which experienced clinicians are able to perform evaluations and teach residents and medical students. Although such clinics offer many benefits to senior and junior clinicians alike, they are devoid of leadership at the student level. Advocates for standardized health and human rights curricula across medical training programs note that in the last 10 years, students have been instrumental in starting elective opportunities in US medical schools where formal programming in this field did not exist.10 The Weill Cornell Center for Human Rights (WCCHR) is an example of a student-led initiative to incorporate human rights education into medical training and provide a much-needed service for asylum seekers.

As the first student-run asylum clinic at a US medical school, WCCHR was founded with the dual mission of providing education and service in the field of health and human rights. The Center conducts forensic medical evaluations for survivors of persecution seeking asylum in the US, and provides medical students with experience in asylum work. WCCHR aims to meet the needs of asylum seekers and medical students at multiple levels by: 1) teaching students to recognize the psychological and physical signs of torture and persecution; 2) recruiting and training clinicians as evaluators; 3) acting as a model for other medical schools; and 4) conducting research and advocacy.

In this paper we detail the design, principles, and implementation of WCCHR so that other medical schools may start their own human rights clinics. This would increase the medical community’s capacity to respond to the increasing demand for forensic evaluation of asylum seekers.

Origins of the health and human rights center

Medical students founded WCCHR in partnership with PHR in 2010. After five years of growth and development, WCCHR now has a diverse and growing team of volunteer clinicians and medical students. The Center’s governance consists of a twenty-member student board and two medical directors from the Weill Cornell faculty with extensive experience in asylum work.

WCCHR has always functioned as a student-run clinic, with support and supervision from its medical directors and other Weill Cornell faculty. Students manage all aspects of the program, including: recruiting and training student and clinician volunteers; coordinating with PHR, attorneys, and clinicians to schedule forensic evaluations; organizing on-going medical care for WCCHR clients; fundraising to support the clinic; and collaborating with community partners to increase awareness around WCCHR’s mission.

Education initiative

Training

Given the sensitive nature of forensic asylum evaluations, WCCHR requires that all medical student and physician volunteers attend a training session prior to conducting their first evaluation. The Education Coordinator organizes biannual, half-day training sessions for student volunteers, modeled on PHR national training courses, and based on the Istanbul Protocol for evaluating alleged victims of torture.11 Participants learn the basics of asylum law, the role of health professionals in working with asylum applicants, and special issues in the evaluation of female and LGBT asylum applicants. They are taught how to identify physical, psychological and gynecological sequelae of torture, how to write a medical affidavit, and how to refer clients for ongoing medical care.

By July 2015, 179 students from Weill Cornell Medical College had been trained to participate in the forensic evaluation of asylum seekers. Over 75% of trained students (137) had observed at least one evaluation, and over half (70) of those had observed more than one. In addition, 172 medical students from other medical colleges have attended WCCHR training sessions, and students at the University of Pennsylvania, Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons, Brown University, and the University of Michigan have started student-run asylum clinics modeled on WCCHR.

Clinicians

The Faculty Coordinator recruits physicians and psychologists to serve as forensic evaluators. Evaluator trainings are conducted by WCCHR’s Medical Directors and cover asylum law, key elements of forensic evaluation as it relates to the volunteer’s specialty, self-care for evaluators, and techniques to enhance the students’ learning experiences. All WCCHR’s evaluators must register with the PHR Asylum Network before participating, as all WCCHR’s requests for evaluations are received from, or referred back to, PHR.

WCCHR now has 28 clinician evaluators, up from two at its start. It has trained 79 health professionals to conduct forensic evaluations, including attending-level physicians, resident physicians, and doctorate-level psychologists. Training clinician volunteers will continue as the number of evaluation requests far exceeds current capacity.

Evaluation processes

WCCHR receives case requests after they have been screened by PHR to assess the legitimacy of the legal representation and the client’s asylum claim. After being accepted by WCCHR, it takes four-six weeks for a case to be placed with a volunteer evaluator. The evaluations are conducted in a clinical setting at Weill Cornell Medical College on weekday afternoons and evenings. Two medical students are present for medical or psychological evaluations, but only one student observes gynecological evaluations. Students prepare for the evaluation by reading the legal affidavit provided by the client’s attorney. Students are also given a sample affidavit and note-taking template specific to the type of evaluation (medical, psychological or gynecological) that they will observe. On the day of the evaluation, the students normally meet with the evaluator to discuss his or her planned approach to the interview.

The evaluator conducts most of the evaluations while the students take notes and are encouraged to ask the clients questions to clarify information for inclusion in the affidavit. At the end of the evaluation, the students assess the client’s interest in obtaining follow-up medical care facilitated by the WCCHR Continuing Care team.

Following the interview, the evaluator conducts a debriefing session with the students to analyze the data collected, discuss how to organize this information in the affidavit, and have the students reflect on their experience of the process. The evaluator also reinforces key points from the training sessions, such as the medical professional’s duty to document findings objectively. Students must complete the first draft of the affidavit within two weeks of the evaluation, which is then finalized by the evaluator, with feedback provided to the students on their draft.

The evaluators find that working with the students’ notes and draft affidavit substantially decreases their workload, although they must assume responsibility for the final affidavit, which is submitted to the client’s attorney.

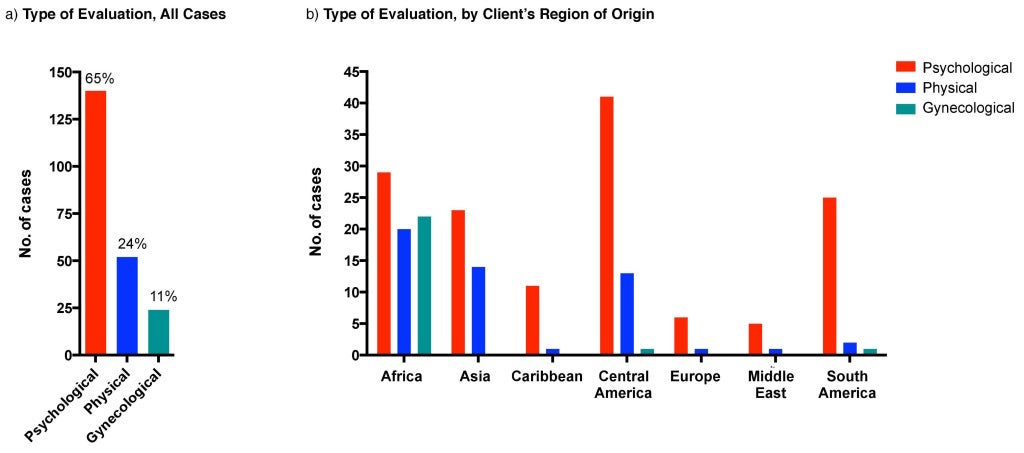

By July 2015, WCCHR had performed 216 evaluations and written 216 affidavits for 184 clients, 87 male (47%), 92 female (52%), one transgender, ranging in age from 11 to 65 years, from 49 countries. The most frequent country of origin is Honduras (22, 11%) and the most frequent type of evaluation is psychological (140, 65%) (Figure 1A). Most clients seeking gynecological evaluations have emigrated from the African continent (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Evaluations by case type and from region of origin

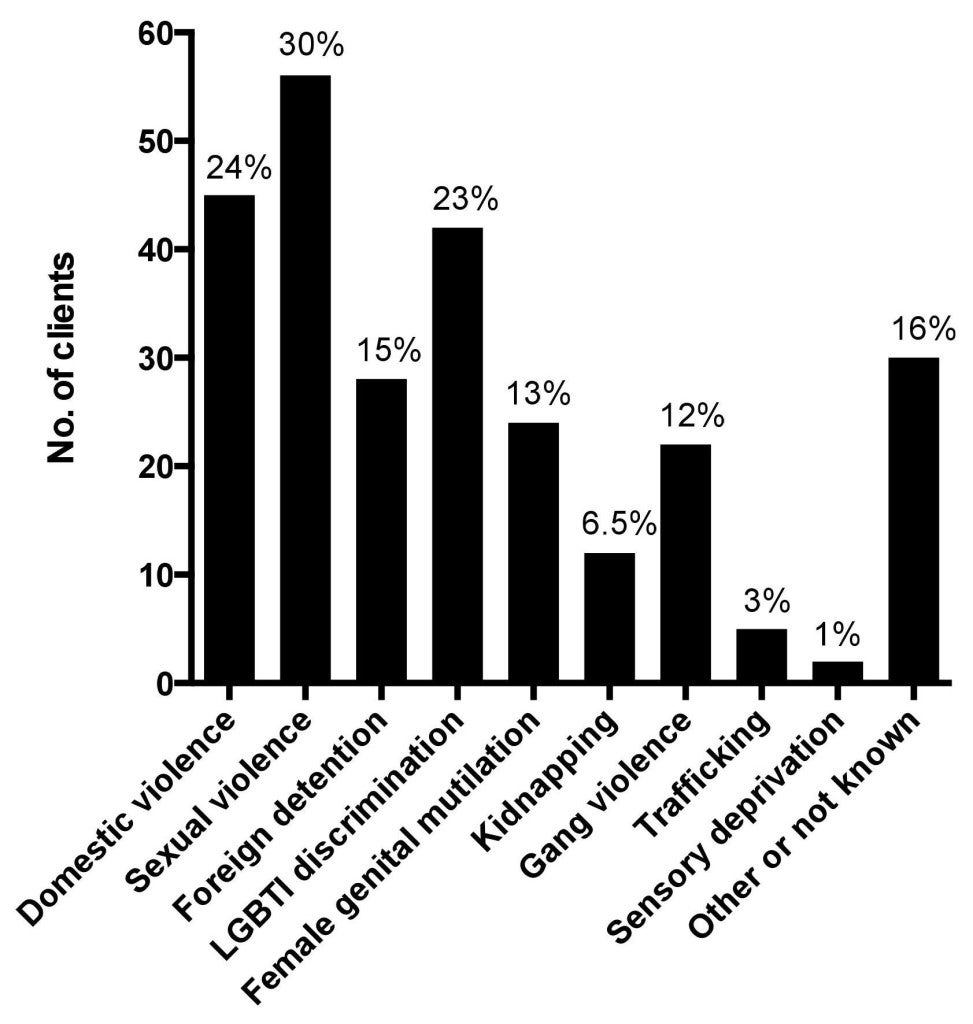

WCCHR clients have sought asylum on the grounds of political opinion, nationality, race, religion, and membership of particular social groups. Nearly one-third of clients reported experiencing sexual violence (56, 30%) (Fig 2). Thirteen percent (25) had experienced female genital mutilation, which represents a quarter of all female asylum seekers seen at WCCHR (Fig. 2). Nearly one-quarter of all clients reported being victims of domestic abuse (45, 24%) or being discriminated against based on their LGBTI status (42, 23%) (Fig 2). Of the 66 clients who have now had their cases heard in court, 94% have been granted asylum or another form of relief, compared to the national average of 89% for asylum seekers with medical documentation.12

Figure 2. Type of persecution or torture reported by clients

Follow-up and feedback

WCCHR relies on feedback to improve its services. The day after each evaluation the students and evaluator are asked for feedback on all aspects of the session, including logistics, the adequacy of the students’ preparation, and the quality of the learning experience for the students. In addition, WCCHR conducts student surveys to assess the impact that the WCCHR experience has had on their medical education (Table 1).

Table 1: Experiences of Medical Students Volunteering with WCCHR

Satisfaction

| Survey statement | Student agreement

N=46(%) |

| The training session adequately prepared me to participate in an asylum evaluation | 38 (83%) |

| I felt that being an observer at an evaluation was a worthwhile experience | 38 (83%) |

| I felt that my evaluator made the evaluation a positive learning experience | 33 (72%) |

| I experienced vicarious trauma through my participation in an evaluation | 5 (10%) |

| I felt that WCCHR provided adequate support and resources for my emotional needs throughout this volunteer experience | 32 (69%) |

|

Overall, I am satisfied with my volunteer experience with WCCHR

|

40 (87%) |

Impact

| Survey statement | Student agreement

N=46(%) |

| I would recommend that a friend join WCCHR | 45 (97%) |

| I am interested in attending another WCCHR evaluation in the future | 40 (87%) |

| My WCCHR experience affected how I plan to integrate service into my future medical career | 36 (78%) |

| I plan to conduct asylum evaluations when I am a physician | 30 (65%) |

The Monitoring and Evaluations Coordinator organizes biannual debriefing sessions with student volunteers to facilitate communication between student participants, the WCCHR Student Board, and the medical directors. Students are given the opportunity to share their experiences in a way that maintains the privacy of the clients, while discussing the rewards and challenges of bearing witness to accounts of torture.

Additional projects

WCCHR’s Continuing Care program was formed in response to student feedback. Several students commented that healthcare professionals have a duty to help clients access ongoing healthcare following forensic evaluations, regardless of the asylum case outcome. The Continuing Care program allows students to act as advocates in this process by assessing clients’ medical needs after each forensic evaluation, then members of the Continuing Care team assist applicants to access such services. WCCHR refers clients to Weill Cornell Community Clinic (WCCC), a student-run clinic that serves the uninsured, and to various organizations offering mental health services across New York City. WCCHR has partnered with the Legal Aid Society to help clients apply for Medicaid insurance. The Center also helps clients find short-term housing and English language courses. Since 2012, the Center has managed 70 referrals for follow-up care and non-medical services.

In April 2014, the Center began using a comprehensive, standardized assessment tool to better evaluate clients’ continuing care needs. Clients are informed that choosing to receive follow-up care is optional and has no bearing on their case. Of the 51 clients surveyed to date, over 70% requested help to arrange follow-up psychological and medical care and 31% (16) wanted further treatment for chronic pain. Most clients were interested in English classes and receiving literature on coping with traumatic experiences (61% and 76%, respectively). Twenty-one clients (41%) wanted help applying for Medicaid health insurance.

Research

WCCHR has a small but growing portfolio of research projects, ranging from a critical look at how the “one year bar” in asylum law disproportionately affects survivors of gender-based violence, to assessing medical students’ attitudes towards torture. Student Board members have presented at national conferences, including PHR’s Asylum Network Training, the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting, and the Unite for Sight 11th Annual Global Health & Innovation Conference. In addition, WCCHR has published a manual, the Asylum Evaluation Training Manual, which is available at WCCHR.com.

Education

While 82% of surveyed students agreed that the training session hosted by WCCHR prepared them to participate in an asylum evaluation, several students reported that they would benefit from additional training. The Student Board is currently working with several Weill Cornell faculty members to strengthen its training program through the creation and implementation of a virtual patient case. This interactive case simulates a full clinical encounter with a patient avatar on the i-Human online platform, and allows students to compare their own notes with an affidavit written by an expert clinician.13 The WCCHR Student Board piloted the virtual patient case at its Fall 2014 Asylum Evaluation Training and will analyze its impact on students’ mastery of the training material and overall sense of preparedness for their initial evaluations.

Community partnerships

WCCHR collaborates with a variety of organizations involved in human rights work. In March 2013, WCCHR launched the first Annual New York Asylum Network Luncheon, bringing together students, physicians, attorneys, social workers, and other professionals who engage in asylum work. The event, repeated yearly since then, has created a forum to discuss the challenges that asylum seekers face in the US, and provided opportunities for collaboration.

Discussion

WCCHR has developed a robust, student-driven, elective health and human rights curriculum at Weill Cornell Medical College, while providing an invaluable service for the asylum-seeking community. In 2014, WCCHR conducted 58 evaluations and wrote 58 affidavits for 48 clients. Twenty-two of the 48 clients were referred to WCCHR by PHR, while the remaining 26 were referred by attorneys. WCCHR accepted at least 20% of the cases PHR placed in New York City in 2014.14 Crucially, the Center’s mentorship model creates a pipeline of future physicians interested in asylum work. Two thirds of students trained by WCCHR agreed that they would like to conduct asylum evaluations when they are physicians. Both student and faculty volunteers consistently offer positive comments about their experiences with WCCHR when feedback is solicited at multiple points throughout the academic year.

Forensic evaluation of asylum seekers is a service in desperate need of greater physician involvement. Despite the best efforts of organizations like PHR and WCCHR, requests for forensic evaluations continue to surpass the capacity of trained clinicians to provide them. Additionally, most human rights clinics only accept cases from clients who have legal representation, which excludes thousands of asylum seekers from obtaining this beneficial service. Inevitably, many immigrants who are fleeing persecution or maltreatment are not aware of, or are unable to navigate, the legal process of applying for asylum. These people are disproportionately harmed by adversarial immigration policies that often deny them the opportunity to find safe haven in the US.

Inadequate access to legal resources is only one of the many challenges that human rights clinics must grapple with when they commit to engaging with the asylum community. Another is securing appropriate ongoing medical treatment for survivors of torture. WCCHR does not have the capacity currently to provide long-term primary and psychiatric care to all of its clients in-house. At volunteer students’ behest, it has developed partnerships with programs around New York City, such as Bellevue’s Program for Survivors of Torture, to which clients are referred.

It is WCCHR’s hope that early exposure to the obstacles to health faced by asylum seekers and survivors of torture will allow medical students to better understand the importance of the social determinants of health, and to effectively engage with vulnerable populations as future physicians. Even if volunteers do not continue conducting forensic evaluations as physicians, participation in student-run asylum clinics will have exposed the medical students to some of the most common physical and psychological manifestations of trauma, a skill that will benefit many of their future patients, asylum seekers or not.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Joseph Shin, Dr. Thomas Kalman, Dr. Laurie Glimcher, Dr. Barbara Hempstead, Dr. Carol Storey-Johnson, Dr. Oliver Fein, Dr. Yoon Kang, Dr. Holly Atkinson, Dr. Alexandra Tatum, and Viviana Espinosa for their ongoing support of WCCHR.

Eleanor Emery, MD, is a resident physician in Internal Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA

Carmen Stellar, MA, is an MD candidate at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY

Krista Dubin, is an MD-PhD candidate at the Weill Cornell/Rockefeller/Sloan-Kettering Tri-Insitutional MD-PhD Program, New York, NY

Taryn Clark, MD, is a resident physician, Section of Emergency Medicine, Department of Medicine, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA

Aynsley Duncan, is an MD candidate at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY

Alejandro Lopez, is an MD-PhD candidate at the Weill Cornell/Rockefeller/Sloan-Kettering Tri-Insitutional MD-PhD Program, New York, NY

Joanne Ahola, MD, is a Medical Director Emeritus of the Weill Cornell Center for Human Rights and an Adjunct Assistant Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at the Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY

Terri Edersheim, MD, is a Medical Director Emeritus of the Weill Cornell Center for Human Rights and a Clinical Associate Professor in the Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Maternal Fetal Medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY

Nicole Sirotin, MD, is a Medical Director Emeritus of the Weill Cornell Center for Human Rights and a Consultant Physician, Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

References

1 Asylum Levels and Trends in Industrialized Countries, 2014. UNHCR (accessed on 2015 July 7). Available at http://www.unhcr.org/551128679.html.

2 Eisenman DP, Keller AS, Kim G. Survivors of torture in a general medical setting: how often have patients been tortured, and how often is it missed. West J Med. 2000;172(5):301–4.

3 FY 2012 Statistical Year Book. United States Department of Justice Executive Office for Immigration Review. Office of Planning, Analysis, and Technology. February 2013. Revised March 2013.

4 Physicians for Human Rights. 2012 Examining Asylum Seekers: A Clinician’s Guide to Physical and Psychological Evaluations of Torture and Ill Treatment.

5 Lustig SL, Kureshi S, Delucchi KL, Iacopino V, Morse SC. Asylum grant rates following medical evaluations of maltreatment among political asylum applicants in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008 Feb;10(1):7-15.

6 The Times Editorial Board, “The immigration court backlog: Why won’t Congress act?” Los Angeles Times, August 26, 2015, accessed September 25, 2015, http://www.latimes.com/opinion/editorials/la-ed-immigration-court-20150826-story.html; Devlin Barrett. “U.S. Delays Thousands of Immigration Hearings by Nearly 5 Years.” The Wall Street Journal. January 28, 2015, accessed September 25, 2015, available at http://www.wsj.com/articles/justice-department-delays-some-immigration-hearings-by-5-years-1422461407.

7 see note 1

8 Cotter EL, Chevrier J, El-Nachef WN, Radhakrishna R, Rahangdale L, Weiser S, Iacopino V. Health and human rights education in US schools of medicine and public health: current status and future challenges. PloS one. 2009 Mar 18;4(3): e4916.

9 Iacopino V. Teaching human rights in graduate health education. Health and Human Rights: the Educational Challenge Boston: François-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights. 2002:21-42.

10 Manual on the Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture and Other Cruel and Degrading Treatment or Punishment. Istanbul Protocol. New York: United Nations; 1999.

11 I-Human Patients, Inc. <www.i-human.com> 2013-2015.

12 see note 5

13 I-Human Patients, Inc. <www.i-human.com> 2013-2015.

14 Meredith Fortin, JD, Asylum Program Officer, Physicians for Human Rights. Personal correspondence to author, September 30, 2015.