Women’s Perspectives on Barriers to Skilled Birth Attendance and Emergency Obstetric Care in Rural Tanzania: A Right to Health Analysis

Vol 27/2, 2025, pp. 317-330 PDF

Prisca Tarimo, Gillian MacNaughton, Tarek Meguid, and Courtenay Sprague

Abstract

Tanzania is among the countries with high rates of maternal mortality. In 1976, Tanzania ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which enshrines the right to health, including maternal health care. This right is further recognized in national law and policy. Despite these commitments, Tanzanian women continue to die from preventable maternal causes. Using a right to health lens, this qualitative study explored the barriers preventing rural underserved women from seeking skilled birth attendance and emergency obstetric care in Ngorongoro, Tanzania, where the use of such services has historically been low. Our study included a document review of maternal health-related laws, policies, and reports issued by governmental and nongovernmental entities, alongside interviews with 32 women of reproductive age. We found that the right to quality maternal health care was constrained by (1) low government budget allocations, (2) a lack of skilled health providers and maternal health care infrastructure and supplies, (3) long distances to health care facilities and a lack of transportation, (4) high cost of transportation and health facility delivery,5) the tradition of home delivery, and (6) distrust that health care facilities would provide respectful and culturally appropriate care. We then generated key recommendations to overcome such barriers and thereby improve rural maternal health care and reduce maternal mortality.

Introduction

Maternal mortality—that is, deaths due to pregnancy- and childbirth-related complications—is a global public health and human rights concern. Worldwide, 800 women of reproductive age die each day from maternal causes that are highly preventable.[1] Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa account for an estimated 70% of global maternal mortality.[2] Tanzania is among these countries with high rates of maternal deaths. According to the World Health Organization, Tanzania’s maternal mortality rate decreased between 2000 and 2020 from 760 to 238 deaths per 100,000 live births.[3] Nonetheless, the rate remains high, underscoring the need for the country to accelerate progress toward achieving Sustainable Development Goal target 3.1: to reduce the maternal mortality rate to fewer than 70 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2030.[4]

Maternal mortality can result from direct medical causes (such as hemorrhage, hypertension, sepsis, and obstructed labor) or indirect causes aggravating or aggravated by pregnancy (such as HIV, malaria, and anemia).[5] However, effective interventions to manage and treat the causes are widely known and can be administered during antenatal care and during and after birth.[6] Significantly, most maternal deaths can be prevented if (1) births are assisted by skilled birth attendants (SBAs) and (2) all births ending in complications (about 15%) receive emergency obstetric and newborn care (EmONC). EmONC refers to a set of nine lifesaving interventions defined by the World Health Organization.[7] In Sub-Saharan Africa, many women, particularly those in rural areas and poorer households, continue to die due to a lack of appropriate care.[8] This is an unacceptable injustice, as women’s health is a fundamental human right.[9]

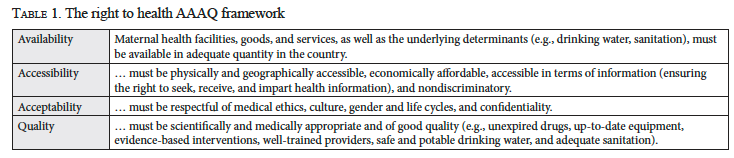

Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights recognizes the right of everyone, including pregnant women, to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, also known as the right to health.[10] General Comment 14 on the right to health, issued by the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, states that the right to health encompasses an entitlement to a system of health protection with functioning health facilities, goods, and services and, further, that governments have the obligation as duty bearers to ensure the availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality (AAAQ) of services women need (see Table 1).[11] This includes the core obligation to improve reproductive, maternal, and newborn health care, including family planning, antenatal care, postnatal care, EmONC and access to information.[12]

In 1976, Tanzania ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, recognizing the right of everyone to health care, including sexual and reproductive health care. The National Health Policy of 2007 also recognizes the right to quality, equitable, affordable, and accessible health care and prioritizes vulnerable groups, including pregnant women.[13]

Moreover, since 2008, the Ministry of Health has implemented an integrated National Plan for Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health. The plan (2016–2020 and 2021–2026) aims to reduce maternal mortality by improving the availability of basic EmONC to 70% of dispensaries and 100% of health centers, and the availability of comprehensive EmONC at 100% of hospitals and 50% of health centers.[14] Lastly, Tanzanian policy stipulates that maternal health services be provided free at the point of service.[15] These strategies align with Sustainable Development Goal target 3.1.

Despite these legal and policy commitments, many women, especially in rural and poor households, continue to lack access to SBAs and critical care during birth. While births with SBAs increased nationwide from 64% in 2015/2016 to 79% in 2019/2020, coverage remains lower in rural areas (42% to 55%), where about 70% of Tanzanians live, compared to urban areas (83% to 87%).[16] Moreover, lifesaving EmONC coverage for women facing obstetric complications, such as cesarean deliveries (C-sections), was lower in rural areas (5% coverage) relative to urban areas (10%).[17] The health sector plan (2021–2026) aims for 85% SBA coverage nationwide and 75% SBA coverage at district council levels and among the poorest households.[18] The extent to which these policies are actually benefiting women on the ground and reducing maternal mortality remains questionable.

Studies across low- and middle-income countries, including Tanzania, have found that high maternal mortality is attributed on the supply side to the poor funding of health systems, understaffing, and the absence of essential infrastructure for quality EmONC—factors that replicate societal inequities of access.[19] On the demand side, studies in rural Sub-Saharan Africa have found several barriers to the use of SBAs and EmONC, including women’s social status (as it relates to education, income, obstetric knowledge, and autonomy), long distances to health facilities, lack of transportation, hospital fees and other costs, cultural beliefs, family responsibilities, and poor quality of care.[20] For example, researchers found that women who lived over 35 kilometers from comprehensive EmONC facilities, such as a hospital, were four times more likely to die of maternal causes than women living 0–5 kilometers from a hospital, as the long distance contributed to more home deliveries and delays in accessing emergency obstetric care.[21] Further, increasing evidence is unveiling how the mistreatment of women by health care providers in facilities makes women hesitant to access health facilities for childbirth.[22] Significantly, women in the poorest 20% quintile are three times more likely to deliver at home, relative to the wealthiest 20% quintile.[23]

In the context of addressing maternal mortality through a human rights lens, we found three studies conducted in rural Tanzania. Using the AAAQ framework, Thomas John et al. assessed health workers’ perspectives on barriers to and strategies for fulfilling women’s right to quality maternal health care.[24] Andrea Miltenburg et al. explored the human rights principles of dignity, autonomy, equality, and safety in their study of women’s experiences of facility-based maternal health care.[25] Lilian Mselle et al. used Thaddeus and Maine’s three-delays model to explore the experiences of women who developed fistula after prolonged labor.[26] Together, these studies concluded that there has been a failure to realize women’s right to accessible and quality maternal health care, attributed primarily to inadequate health care resources, providers’ negative attitudes, and inequitable access owing to long distances, poor transportation, and high costs. Additional context-specific, rights-based studies are needed to illuminate why rural communities are left behind and to inform context-appropriate, rights-based solutions. Accordingly, we applied the AAAQ framework to explore women’s perspectives on barriers to using SBAs and EmONC in Ngorongoro, Tanzania, an underserved rural district.

Methods

Study setting

Ngorongoro is a rural district of Arusha, Northern Tanzania. Its estimated population of 200,000 consists predominately of Maasai pastoralists (80%) and agropastoral Watemi or Sonjo people (11%).[27] Historically, Maasai pastoralists in Ngorongoro and other areas of Tanzania have experienced marginalization and loss of land rights and other resources, which has made them socially and economically vulnerable.[28] We selected Ngorongoro due to its high maternal mortality rate (383 per 100,000 live births) compared to the national maternal mortality rate (238 deaths per 100,000 live births).[29] The district also has comparatively poor maternal health indicators. Only 55% of deliveries occur in a health facility, compared to the national average of 83%.[30] Generally, low utilization of SBAs during delivery has been persistent in the district.[31] The district is divided into three administrative divisions: Loliondo, Sale, and Ngorongoro. There are 33 health facilities—2 hospitals, 5 health centers, and 26 dispensaries—providing delivery care. Comprehensive EmONC, such as C-sections, is provided only in the hospitals.

Design and methods

We used a right to health framework (AAAQ) and qualitative methods to explore the perspectives of rural women on barriers preventing delivery in health facilities and utilization of EmONC. First, we conducted a review of international human rights law and policy on the right to health and preventable maternal mortality, as well as Tanzanian laws, policies, plans, reports, and surveys on health system strengthening and maternal health, to understand the policy background and progress to date. Examples of documents reviewed include the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; General Comment 14; Sustainable Development Goal 3.1; Tanzania’s Health Sector Strategic Plan (2015–2020 and 2021–2026); the National Plan for Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health (2015–2020 and 2021–2026); the Health Sector Strategic Plan IV, 2015–2020 Review (September 2019); and the Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey (2015–2016).

Second, based on the document review and a 2018 pilot study, we created a semi-structured interview guide to conduct face-to-face interviews in 2021 with 32 women aged 18–49 with children aged 0–24 months. Participants responded to questions about where they had their last birth, why they chose facility or home delivery, and what barriers they perceived to health facility delivery and quality EmONC during emergencies. Two (of three) administrative divisions were purposively sampled: Loliondo (town) and Sale (remote). A trained field researcher recruited participants in person from eight health facilities (one hospital, five health centers, and two dispensaries) where they attended child-well clinics. The researcher obtained verbal informed consent from each participant for conducting and recording the interviews. Interviews ranged from 30 to 90 minutes, were conducted in Swahili, and were later transcribed into English by the first author. Data from the interviews and documents were analyzed thematically based on the AAAQ framework. ATLAS.ti software was used to analyze interview transcripts. The use of both document review and women’s interview narratives increased the trustworthiness of the data, through the triangulation of information sources. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from Tanzania’s National Institute for Medical Research (Ref No. NIMR/HQ/R.8a//Vol.IX/3430) and the University of Massachusetts Boston (2019187).

Findings and analysis

Demographic characteristics of participants

Of the 32 women, the majority were pastoralists and agropastoralists, signifying poor households. Fourteen were Maasai, 12 were Watemi (Sonjo), and the remainder belonged to other tribes; 21 were married and 11 were unmarried; 20 had completed primary school, 7 had finished secondary school, 3 held diplomas, 1 held a college degree, and 1 had no schooling. Regarding place of childbirth, 28 had given birth at health facilities and 4 at home. Including previous births, at least 11 women had had home births with traditional birth attendants (TBAs) or family assistance; 8 women had had only one birth experience. Facility-based deliveries included 10 at the hospital, 10 at health centers, and 8 at dispensaries; 26 women had experienced natural deliveries, while 6 had undergone C-sections.

Based on the AAAQ framework of the right to health (Table 1), we present the perspectives of these rural women on barriers to using SBAs and EmONC in facilities and place these perspectives in context utilizing our document review.

Availability

The right to health requires that health facilities, providers, goods, and services be available in sufficient quantity in the country to ensure that women can access and utilize SBAs before, during, and after birth.[32] Findings from the document review demonstrate that the Tanzanian health care system overall, and Ngorongoro District specifically, suffer a shortage of health facilities, providers, and supplies needed to ensure the availability of quality maternal health care. Women’s narratives also reinforced this finding, illustrating how this lack of resources acted as a barrier for women to access and deliver in health facilities. States are required to ensure maximum available resources to finance maternal health care. Tanzania, however, a lower-middle-income country, spends little on health care. In 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, government health expenditure as a proportion of total expenditure was 6% and 8%, respectively, below the 15% recommended by the African Union Abuja Declaration.[33]

Regarding the availability of health facilities, the Primary Health Care Service Development Programme (2007–2017) aimed to improve equity of access to maternal health care by increasing rural primary health care facilities and requiring every village to have a dispensary, every ward to have a health center, and every district to have a council hospital. Nationally, achieving the program target required 16,487 health facilities of all types in Tanzania. However, by 2020, only 8,665 health facilities were available—just 50% of the program goal.[34]

At the Ngorongoro District level, there was an acute shortage of health facilities (60% shortage), especially for primary health care.[35] Although there are an adequate number of hospitals for comprehensive EmONC population-wise, the lack of adequate lower-level health facilities contributed to many women in remote areas giving birth at home. As one woman reported:

Of my five children, the first three were delivered at home because there were no health facilities nearby; I had gone to the wilds at Ngusero to herd cattle and there were no health facilities there. (participant #14)

Another participant stated:

In this area, we do not have enough health facilities. They also have limited staff who have many patients to attend to. (participant #28)

Regarding availability of health professionals, our document review found that Tanzania had a 52% shortage of the required health workforce. Only 95,827 of 208,595 available staff positions had been filled.[36] Regarding distribution, only 54% of the workforce worked in rural areas where 70% of Tanzanians live. In Ngorongoro, the shortage was higher: 72%.[37] Similarly, women reported insufficient health providers and their absence on-site when women needed help. Participants explained:

At the antenatal clinic, they will advise you to deliver in a health facility. The problem is that in our ward we have a new dispensary, but it is not providing health services yet due to lack of health care providers. As a result, we have to go to the health center, which is far from here. (participant #30)

Yesterday … there was a woman who struggled to give birth … and lost her baby at the health center because there was no skilled midwife available to help her. The family later called a TBA who came and helped her give birth in the health center, but the baby died. (participant #8)

Women described most primary facilities as lacking adequate medicines, supplies, and beds for labor and delivery. One participant lamented:

Sometimes the doctors do not have equipment, such as gloves, and this encourages women to give birth at home. If you come here and they do not have gloves, … they will just give you a referral or send you home. Sometimes women end up giving birth on the way before getting home. (participant #15)

Another participant stated:

I was not pleased with the condition of the labor ward. They do not have enough beds. Each bed was shared by two or more women which I do not think is healthy. (participant #3)

A dearth of funding, facilities infrastructure, and skilled health professionals also affected the availability of EmONC. Women reported that most health centers and dispensaries in rural areas lacked quality EmONC to stabilize women with complications, requiring referrals. Emergency referrals were also challenging because only one ambulance functioned in the district. Comprehensive EmONC was provided only at the two hospitals, despite guidelines requiring at least 50% of all health centers in underserved areas to provide comprehensive EmONC. One participant explained:

There is lack of advanced services at the dispensary. If a woman has complications, they have to call an ambulance from Loliondo to come and take her to the hospital. For example, if someone needs surgery, they have to go to the hospital in Loliondo, which is very far from here [150 kilometers]. We also have few health workers. (participant #18)

Another participant exclaimed:

I could have died if I had delivered here at the health center because they do not have services for blood transfusion, and it would have taken longer for me to get to the hospital because of the long distance. (participant #30)

Nationwide, basic EmONC is available at only 20% of dispensaries and 39% of health centers relative to the 70% and 100% required, respectively.[38] Comprehensive EmONC is available at only 80% of hospitals and 50% of health centers (but up from 17% of health centers in 2017), compared to the 100% and 70% required.[39]

Accessibility

Accessibility means that maternal health services must be within safe geographical distance, affordable, and nondiscriminatory, and must ensure access to information.[40] Evidence revealed that facilities’ geographical inaccessibility hindered rural women from accessing skilled delivery care, including timely EmONC during complications. The district’s remoteness and the limited number of facilities in rural areas put communities, especially pastoralist nomads, far from services, especially hospitals. Women from the Sale community (remote division) reported having more difficulty accessing services requiring C-section and blood transfusions at Wasso hospital (64–116 km), compared to Loliondo women (0–35 km). They also reported that women in isolated rural areas often gave birth at home due to the high risk of giving birth on the roadside while traveling to facilities. In most cases, facility care was pursued as the last resort, when home deliveries ended in complications. One participant recounted:

We live very far from this dispensary. Some women are worried that they might give birth on their way to the hospital. Even this child was born while on our way to the dispensary. I had traveled a long distance from home to here [64 km to hospital]. (participant #22)

Another participant explained:

Maternal deaths are unavoidable in this community because health services are very far from people’s residences. For example, if you develop a major complication you will have to go to Wasso hospital, which is very far from here. You might lose your life before you arrive. If health services are brought near to us, we will be able to cut down a lot of maternal deaths. (participant #30)

Poor transportation, one functioning ambulance, poor roads, and seasonal rains also hindered access to facilities, especially during emergencies. Many rural women reported walking long distances to health facilities (up to two hours) or using motorbikes (bodaboda). Those developing complications at home or at primary facilities would have to hire expensive private transportation to a hospital. Two participants elaborated:

Sometimes you have to travel 60 kilometers to reach a health facility. Unfortunately, at this place, bodabodas are the common means of transportation. However, motorcycles are not safe for a pregnant woman. She may give birth before reaching a health facility due to poor roads. Most roads are inaccessible during rainy season. (participant #10)

Now there is only one ambulance that is also not reliable. We may request the ambulance, but the driver may not come … or by the time the ambulance reaches her, she is already dead and left the child behind. Sometimes both the mother and the child die. (participant #1)

These conditions made transportation costs unaffordable for most women in rural areas. As one recalled:

I ended up giving birth at home because we did not have access to transportation. There were no motorcycles nearby and it was too expensive to hire a car. (participant #15)

Hospital fees also encouraged home delivery. Maternal and child health services are exempted from user fees in Tanzania.[41] However, some women reported paying out-of-pocket fees for C-sections and birthing supplies required by facilities. Participants perceived hospitals as more costly than health centers and dispensaries, and therefore, pastoral and poor women avoided them. One participant recalled:

I paid for the operation [C-section] after I was referred to the hospital and for the equipment and supplies used. Those who give birth naturally bring only their own gloves and other supplies needed such as medicine for IV drips and delivery kit. (participant #28)

Another participant explained:

Not all women are able to buy the supplies needed for childbirth. Sometimes because of lack of education and low income, it may be difficult for some women to prepare or pay for the supplies needed during childbirth. (participant #9)

A Maasai woman reported that women unable to pay for services were sometimes denied services, an experience that discouraged them from returning: “Sometimes, you may be denied services and die just because you did not have money to pay upfront for the care needed” (participant #8).

Another participant remarked, “Some of them [women] do not have money to meet their basic needs such as food while at the hospital” (participant #12).

Furthermore, facility rules that imposed penalty fees or deny care to women who did not comply with antenatal care attendance also encouraged home delivery. One participant reported:

Most of those who give birth at home are those who did not have a supportive partner to attend antenatal clinic with … as required. When they fail to attend antenatal clinic, they decide to give birth at home because some health facilities would charge them a fee when they go for delivery, as a penalty for not attending clinic, for services that they deserve to obtain free. (participant #31)

Low community awareness of the importance of giving birth in facilities also impacted accessibility. Women in remote areas, those with poor antenatal care attendance, women with low education levels, Maasai, and those with language barriers had little awareness and limited access to health information. Also, some women reported that men’s low awareness of and involvement in maternal care limited facility delivery because most households and financial decisions were made by husbands:

Women may not be able to deliver in health facilities because their partners are not supportive. Low awareness makes people overlook the benefits of health facility delivery. Most education and counseling tend to focus on pregnant women without involving men. As a result, men may not be supportive of their wives delivering in health facilities. (participant #10)

Other accessibility barriers included women’s household responsibilities and not having someone to accompany her to a health facility.

Acceptability

Acceptability means that maternal health services must be respectful of medical ethics, culturally appropriate, and sensitive to gender, age, and life-cycle requirements.[42] Women reported that the tradition of home births, distrust of facility birth practices, non-preference for young and male attendants, disrespect from health providers, and language were barriers to facility births.

Participants indicated that pastoral women were inclined to prefer home delivery because, like their ancestors, they trusted TBAs more than health facilities. One participant explained, “Within the Maasai culture, women still prefer and believe in TBAs to help them deliver safely, and that is the reason they continue to deliver at home with TBAs” (participant #2). At the same time, some participants recognized that TBAs lacked the clinical skills and supplies needed for safe delivery:

A lot of women die during birth. In Maasai communities, traditional midwives are the ones helping women give birth at home. TBAs do not have any tools to monitor labor progress. They just examine women manually and continue to hold them even when there is a problem. Your husband may listen to the TBA rather than your choice. (participant #17)

Although TBAs have been banned by the government from assisting home deliveries, they can accompany women to health facilities and, when needed, assist deliveries under SBA supervision. Participants said that some TBAs have accepted this change but that in isolated areas, TBAs are the only help available.

Pastoral women also believed in natural births and disapproved of C-sections. Pastoral women were concerned that hospitals conducted “unnecessary” C-sections, and consequently, they avoided giving birth at hospitals. Others intentionally delayed seeking facility care after the onset of labor to avoid prolonged labor at facilities, which could lead to referral for a C-section. However, such delays put women at risk of delivering at home and did not reduce complications requiring C-sections. Participants also disliked multiple vaginal examinations. Some believed that excessive examinations obstructed labor and led to C-sections. One participant opined

They believe that they will be operated on [C-section] if they stay at the hospital for a long time without being able to give birth naturally. Sometimes, a woman may be forced into surgery. Another thing, … they conduct women exams [vaginal examination]; this is too much … to the extent that you get swollen [cervix]. Every time a different doctor or nurse starts a shift, they check you with their fingers and frequently. In the end, they tell you that you are swollen … you cannot push … you need an operation. This is very discouraging to an extent you do not want to go back. (participant #4).

Another participant explained:

They [women] believe that operations are hospital projects for getting money. A few know that C-sections are done to save the life of the mother and her baby. (participant #10)

Other factors limiting the acceptance of C-sections included women’s low education level, C-section costs, pastoral women’s lack of autonomy in consenting, and long recovery times restricting participation in daily activities.

We also found that pastoral women, especially older women, disliked being attended by male midwives and younger birth attendants. Traditionally, TBAs have been older women. One participant recounted:

We do not feel comfortable being attended by male midwives. This is not something we are used to. For example, when I came to give birth, I was being helped by a young male doctor. I told the nurse that I do not want to be attended by someone who is young. (participant #18)

Cold facilities and those disallowing family members to stay with women for emotional and physical support due to lack of space also created discomfort:

I went with my mother. However, she left before I gave birth because she was not allowed to stay. I was angry because of the pain. I wondered, “Did my mother bring me here and leave me to die alone?” (participant #1)

Equally, women reported that their experiences of provider disrespect, mistreatment, and discrimination were barriers. Some participants felt ignored, neglected, and scolded concerning their needs. As one participant stressed:

As … Maasai, we are used to giving birth at home. At the hospital, they mistreat us so much that most Maasai women do not want to go back. When women cry for labor pain, or need help, they tell us we do not have any pain. When you feel that the baby is ready to come and tell them, they say you are not ready and chase you back. And … when you go wait outside and suddenly gave birth by yourself, they charge you fine [a cleaning fee] and become harsh at you although they are the ones who refused to help you. (participant #8)

These women reported feeling helpless and not knowing where to complain about their mistreatment. The few who knew where to submit complaints (e.g., to the person in charge at the facility or village leader) feared future mistreatment if they complained. One participant stated:

I do not know … what to do and where to go if I have been mistreated or denied my rights as a patient. We need more education so that women know their rights during pregnancy and childbirth and where they can complain when mistreated. They should be informed whether such care is freely available or not. (participant #4)

Language was another barrier to using facility services, especially for pastoral women with little education. Participants reported that most facilities were attended by “Swahili” providers (outsiders who could not speak Maasai or Sonjo) and lacked certified language interpreters. Usually, women unable to speak Swahili received help from a family member, another patient, or hospital staff who spoke both languages. However, this lack of privacy and confidentiality made the women uncomfortable about discussing their health issues. It also left participants feeling that their health care needs were only partially addressed. This experience also discouraged future facility care. One participant explained:

Language is a huge barrier for Maasai women to access health care because providers and women do not understand each other. A nurse may not understand the real health problem the woman has. I, myself, have helped some patients who did not speak Swahili with interpretation while I was at the dispensary to obtain care. (participant #19)

Another participant suggested that “the government could also hire more doctors that speak Maasai language,” noting that a Maasai woman may avoid going to a health facility because she felt disrespected by the doctor, when in fact it was largely a misunderstanding due to language (participant #25).

Quality

Quality means that health facilities, goods, and services must be scientifically and medically appropriate and of good quality. This requires skilled medical personnel, scientifically approved and unexpired medicines, hospital equipment, safe and potable water, and adequate sanitation.[43]

Most women who gave birth in a health facility were assisted by a nurse, a midwife, a clinical officer, or a doctor—all of whom, by definition, are skilled health professionals. Nonetheless, the majority reported experiencing poor-quality and unscientifically appropriate care, including waiting long hours to receive care. Some participants observed other women giving birth alone or with the help of a TBA, and women and babies died due to delayed care. According to participants, these delays and poor care were caused mainly by a shortage of skilled providers, provider absenteeism, limited service hours, and neglectful attitudes of some providers. One participant explained:

Currently, if a woman comes to the dispensary at night to give birth, the health workers may take longer time to respond. This is not safe because some women have already gone through a lot of pain by the time they get here because of the long distance traveled from home. Some women even give birth on the floor while already at the dispensary while waiting for help. (participant #20)

Another participant similarly stated:

Sometimes the nurses are rude. When I got here at the health center at night and was desperately in need of help, the nurse who was here refused to assist me because it was not her shift. I was just outside lying on the floor waiting in pain without help. (participant #10)

Limited space and beds in maternity wards also contributed to poor care, including delayed delivery, lack of privacy, and post-delivery discharge before the medically recommended time. One participant revealed:

They have few health workers who are overloaded by many patients … Also, there might be two women giving birth at the same time but only one delivery bed is available. As a result, they will tell you to stop pushing until the other woman finishes giving birth. (participant #28)

Another participant reported:

Sometimes you are chased home [discharged] from the hospital even if you are still sick and need more close care. They chase us home so that they can have space for another patient. Some people go home and die because they were sent home early before they get better. (participant #8)

Generally, the women rated the quality of health care in facilities using phrases such as “it was okay,” “not very good,” “50/50,” “just normal.” The hospital was perceived as providing better-quality care than health centers and dispensaries, followed by private (faith-based) health centers. Women’s negative birth experiences influenced their decisions to give birth at home or to travel far distances for better care elsewhere. One participant viewed her past experience positively, prompting her to return:

I decided to give birth at this health center because they provide good services. Both my children were born here. I had received good care and support from the doctors for my first child and that motivated me to come back for my second birth as well. (participant #27)

Discussion

Using an AAAQ framework, we conducted a document review paired with interviews with underserved pastoral and agropastoral women in rural Tanzania to identify key barriers limiting these women from exercising their right to SBAs and EmONC.

Availability

Our findings show that there are limited maternal health care resources nationally and in Ngorongoro District, which limits women’s ability to exercise their right to health care during childbirth, including delivering in health facilities with SBAs and accessing EmONC. Findings revealed insufficient primary and EmONC infrastructure, including a shortage of health professionals and a lack of supplies needed to ensure service availability. For example, the district had a 60% shortage of health facilities and a 72% shortage of human resources.[44] The shortage of health professionals was evident, as women reported experiencing or seeing other women giving birth without an SBA (either by themselves or with a TBA), while the lack of commodities such as gloves required preventable referrals, an experience that discouraged women from returning to these facilities. Other studies in Tanzania and Sub-Saharan Africa have similarly found a shortage of health professionals, inadequate infrastructure, and lack of supplies as barriers to SBA and EmONC.[45] Meanwhile, the government’s health care budget remains far below the 15% of total expenditure recommended in the Abuja Declaration. To improve maternal health outcomes, the government—as the duty bearer in fulfilling the right to health—must allocate adequate funds for health care and prioritize maternal health care resources.

Accessibility

In Tanzania, at least 90% of the population lives within 5–10 kilometers of a primary health facility. Our findings reveal, however, that women in remote areas of Ngorongoro, especially pastoral women, face significant barriers to accessing health facilities for maternal health care, especially EmONC. These barriers include long distances to health facilities, lack of transportation, poor roads, poverty, transportation costs, and unofficial fees. For example, although maternal health care is officially exempted from user fees in Tanzania, women reported paying for C-section deliveries and supplies used during birth at some facilities. These costs drove women to deliver at home with TBAs whose services were free and close to home. Women sought facility care mostly when home births ended in complications. Previous studies in rural areas of Tanzania and Sub-Saharan Africa similarly documented long distances, lack of transportation, and user fees as barriers to facility delivery in rural areas.[46] Both the John et al. and Strong et al. studies in rural Tanzania found pregnant women paying for exempted services, including C-sections.[47]

Additionally, some rural women with low awareness of where to access maternal health care and of the benefits of giving birth in a health facility succumb to misinformation, another barrier to facility delivery. Moazzam Ali et al. and others also found low community awareness and limited information access among nomadic populations as barriers to maternal health care utilization.[48] Beyond the fees documented by previous studies, we found that health facilities were imposing penalty fees for delivery on women who had not attended antenatal care. Rather than encouraging antenatal care, these penalties discourage facility-based delivery for those who cannot afford antenatal care or penalty costs. Our findings underscore that insufficient government funding limits effective implementation of the exemption policy for maternal health care, often forcing providers to ask women to help finance their health care.

Acceptability

Our findings reveal both structural and behavioral factors that normalize the mistreatment of women during birth and limit the provision of culturally sensitive and ethical maternal care.[49] Women reported distrusting health care providers and avoiding births in health facilities due to fear of and experiences of disrespect, mistreatment, and unsupportive care from health providers; pastoralist and poor women reported the worst treatment, including being scolded and neglected, having their movement restricted, and being silenced when they called for help. Pastoral women, especially older women, disliked being attended by male birth attendants and undergoing frequent vaginal examinations, and they were concerned about C-sections being performed without their consent. These fears encouraged births with TBAs, who, although unskilled, are female and support natural births. Interestingly, John et al. had similar findings. Although they interviewed health professionals rather than women, the authors found that acceptability barriers to facility births encompassed disrespect by health care providers, unfulfilled women’s preferences, lack of emotional support, unacceptance of male birth attendants, and lack of confidentiality.[50]

Obstetric violence, including disrespectful care, decreases women’s confidence to seek help during birth.[51] The Kate Ramsey et al. study in Tanga, Tanzania, concluded that the mistreatment of women during childbirth is systemic, rather than a series of isolated incidents, often normalized by system actors and even expected by women due to facilities’ lack of resources, providers’ pressure to perform, misaligned incentives, and poor enforcement of respectful maternity care policies.[52] Similarly, our findings demonstrate that women were likely to be ignored or scolded when they did not have the supplies requested (e.g., gloves), when there was one provider attending multiple women, and when women did not provide incentives (or a bribe) to a provider. Women also reported feeling alone during labor because health facilities did not allow a companion in the labor room due to a lack of space and the privacy concerns of other women sharing the space. Further, women reported that labor facilities were cold. To increase trust in the health system among pastoral women in Ngorongoro, interventions implemented include those allowing TBAs to accompany women to health facilities during birth to provide support and help with delivery while supervised by an SBA. However, due in part to language barriers (because TBAs, unlike providers, often do not speak Swahili), TBAs can sometimes end up interfering with SBAs during labor. Nonetheless, one West Africa study found that labor companions can reduce the mistreatment of women during childbirth, while providing emotional support.[53]

Quality

Women’s narratives suggested that reaching health facilities alone does not guarantee receipt of skilled, quality care, especially when SBAs were not available on-site 24/7 or were insufficient in number to ensure timely quality care, and when infrastructure and material resources were insufficient to facilitate skilled and respectful care provision. For example, participants perceived EmONC at health centers to be of poor quality due to the lack of maternity wards and emergency vehicles to ensure timely referral care. Overall, participants reported delays, neglect, mistreatment, and language constraints, all signifying substandard care.[54] These negative higher-quality facilities farther from home. Study participants wished for maternal health care to be timely, supportive, and respectful of women and their cultures. Other studies suggest that when a woman decides whether to give birth at a health facility, the quality of care—especially provider attitudes—may be as important as distance to the facility.[55]

Conclusion

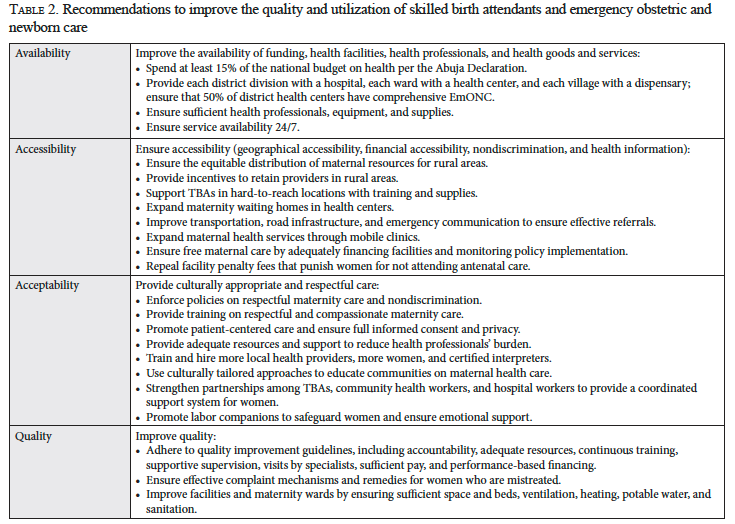

Using a right to health lens, paired with document review and interviews with underserved pastoral and agropastoral women in rural Tanzania, we elevated the voices of these women and their recommendations for maternal health care. The women desire delivery services that are humane—that is, timely, responsive, compassionate, and respectful—and that meaningfully engage women before and during procedures. In particular, they emphasized the need to increase resources to ensure women’s access to the free maternal care to which they are entitled and to improve quality EmONC at primary facilities. In Table 2, we summarize further recommendations, drawn from our evidence, to strengthen maternal service delivery and utilization so that Tanzania can meet its legal obligations to ensure the full realization of the right to maternal health, reduce preventable maternal mortality, and make progress toward achieving Sustainable Development Goal target 3.1.

Study limitations

Our findings are not generalizable to all rural areas of Tanzania but are likely to be relevant among other pastoral communities in Tanzania. Future research could apply other right to health principles—such as accountability, transparency, and participation—together with the AAAQ framework, in similar local and international settings.

Prisca Tarimo is a PhD candidate in the School for Global Inclusion and Social Development at the University of Massachusetts Boston, United States.

Gillian MacNaughton, JD, MPA, DPhil, is a co-founder of Social and Economic Rights Associates; a senior fellow with the Program on Human Rights and the Global Economy and Northeastern University School of Law; and an affiliated researcher with the Research Program on Economic and Social Rights at the University of Connecticut, United States.

Tarek Meguid, MD, MPhil, DTM&H, LLB, MSt, is a consultant obstetrician and gynecologist at Intermediate Hospital Rundu, Kavango East, Namibia, and an honorable associate professor at the Department of Child Health, University of Cape Town, South Africa.

Courtenay Sprague, PhD, joint-MA, is an associate professor of global health, jointly appointed in the Department of Conflict Resolution, Human Security and Global Governance at the McCormack School of Policy and Global Studies and the Department of Nursing at the Manning College of Nursing and Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Boston, United States.

Please address correspondence to Prisca Tarimo. Email: prisca.tarimo001@umb.edu.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2025 Tarimo, MacNaughton, Meguid, and Sprague. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

[1] World Health Organization, UNICEF, UNFPA, et al., Trends in Maternal Mortality 2000 to 2020: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and UNDESA/Population Division (2023).

[2] Ibid., p. xiv.

[3] Ibid., p. 66.

[4] United Nations General Assembly, Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, UN Doc. A/RES/70/1 (2015), target 3.1.

[5] L. Say, D. Chou, A. Gemmill, et al., “Global Causes of Maternal Death: A WHO Systematic Analysis,” Lancet Global Health 2/6 (2014).

[6] O. M. Campbell and W. J. Graham on behalf of the Lancet Maternal Survival Series Steering Group, “Strategies for Reducing Maternal Mortality: Getting on with What Works,” Lancet 368/9543 (2006); World Health Organization, Monitoring Emergency Obstetric Care: A Handbook (2009).

[7] Campbell and Graham (see note 6).

[8] United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, The Millennium Development Goals Report 2015 (2015).

[9] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI) (1966), art. 12(1).

[10] Ibid.

[11] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000), paras. 8, 12.

[12] Ibid., para. 14. See also Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 22, UN Doc. E/C.12/GC/22 (2016), paras. 11–28; Human Rights Council, Technical Guidance on the Application of a Human Rights-Based Approach to the Implementation of Policies and Programmes to Reduce Preventable Maternal Morbidity and Mortality, UN Doc. A/HRC/21/22 (2012), para. 20.

[13] Ministry of Health, Health Policy (2007), paras. 3, 4.2, available at https://www.eahealth.org/policy-publications/tanzania-health-policy-in-kiswahili-2007.

[14] Ibid.; Ministry of Health, The National Road Map Strategic Plan to Improve Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health in Tanzania (2016–2020): One Plan II (2015); Ministry of Health, National Plan for Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health and Nutrition (2021/2022–2025/2026): One Plan III (2021).

[15] Ministry of Health, Health Sector Strategic Plan III: July 2009–June 2015; “Partnership for Delivering the MDGs (2009), p. 47.

[16] Ministry of Health, National Bureau of Statistics, Office of the Chief Government Statistician, and ICF, Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey 2015–16 (2016); Ministry of Health, Health Sector Strategic Plan (HSSP) IV, 2015–2020 Review (September 2019).

[17] Ministry of Health (2019, see note 16).

[18] Ministry of Health, Health Sector Strategic Plan July 2021–June 2026 (HSSP V): Leaving No One Behind (2021).

[19] A. Geleto, C. Chojenta, A. Musa, and D. Loxton, “Barriers to Access and Utilization of Emergency Obstetric Care at Health Facilities in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review of Literature,” Systematic Reviews 7/183 (2018); D. Bintabara, A. Ernest, and B. Mpondo, “Health Facility Service Availability and Readiness to Provide Basic Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care in a Low-Resource Setting: Evidence from a Tanzania National Survey,” BMJ Open 9/2 (2019); A. E. Yamin, “Five Lessons for Advancing Maternal Health Rights in an Age of Neoliberal Globalization and Conservative Backlash,” Health and Human Rights 25/1 (2023).

[20] Geleto et al. (see note 19); R. Dahab and D. Sakellariou, “Barriers to Accessing Maternal Care in Low Income Countries in Africa: A Systematic Review,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17/ 12 (2020).

[21] C. Hanson, S. Gabrysch, G. Mbaruku, et al., “Access to Maternal Health Services: Geographical Inequalities, United Republic of Tanzania,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 95/12 (2017).

[22] R. Khosla, C. Zampas, J. P. Vogel, et al., “International Human Rights and the Mistreatment of Women During Childbirth,” Health and Human Rights 18/2 (2016); A. S. Miltenburg, F. Lambermon, C. Hamelink, and T. Meguid, “Maternity Care and Human Rights: What Do Women Think?,” BMC International Health Human Rights 16 (2016).

[23] M. E. Kruk, S. Hermosilla, E. Larson, et al., “Who Is Left Behind on the Road to Universal Facility Delivery? A Cross-Sectional Multilevel Analysis in Rural Tanzania,” Tropical Medicine and International Health 20/8 (2015).

[24] T. John, D. Mkoka, G. Frumence, et al., “An Account for Barriers and Strategies in Fulfilling Women’s Right to Quality Maternal Health Care: A Qualitative Study from Rural Tanzania,” BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18/352 (2018).

[25] Miltenburg et al. (see note 22).

[26] L. Mselle, T. W. Kohi, A. Mvungi, et al., “Waiting for Attention and Care: Birthing Accounts of Women in Rural Tanzania Who Developed Obstetric Fistula as an Outcome of Labor,” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 11/75 (2011); S. Thaddeus and D. Maine, “Too Far to Walk: Maternal Mortality in Context,” Social Science and Medicine 38 (1994).

[27] Prime Minister’s Office, Regional Administration and Local Government, Ngorongoro District Council Comprehensive Health Plan (CCHP) 2020/21 (2020).

[28] United Nations Human Rights Council, “Cultural Survival: Observations on the State of Indigenous Human Rights in the United Republic of Tanzania in Light of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Prepared for United Nations Human Rights Council: September 2015 2nd cycle of Universal Periodic Review of Tanzania 25th session of the Human Rights Council” (September, 2015).

[29] Prime Minister’s Office (2020, see note 27); M. Piatti-Fünfkirchen and M. Ally, Tanzania Health Sector Public Expenditure Review 2020 (World Bank, 2020), pp. 41–45.

[30] Ministry of Health (2019, see note 16).

[31] M. Magoma, J. Requejo, O. M. R. Campbell, et al., “High ANC Coverage and Low Skilled Attendance in a Rural Tanzanian District: A Case for Implementing a Birth Plan Intervention,” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 10/1 (2010).

[32] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 11), para. 12(a).

[33] Ministry of Health, National Health Accounts (NHA) for Financial Years 2020/21 and 2021/22 (2023); World Health Organization, The Abuja Declaration: Ten Years On (2010).

[34] Ministry of Health, HSSP V (see note 18), pp. 16–18.

[35] Prime Minister’s Office (2020, see note 27); Prime Minister’s Office, Regional Administration and Local Government, Ngorongoro District Council Socio-Economic Profile (2018), p. 6.

[36] Ministry of Health (2019, see note 16), p. 75.

[37] Prime Minister’s Office (2020, see note 27).

[38] Ministry of Health (2019, see note 16); Ministry of Health, Ifakara Health Institute, and the Global Fund, Tanzania Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA) Report 2023 (2024).

[39] Ministry of Health (2019, see note 16); Ministry of Health (2024, see note 38).

[40] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 11), para. 12(b).

[41] Ministry of Health (2009, see note 15), p. 47.

[42] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 11), para 12(c).

[43] Ibid., para.12(d).

[44] Ministry of Health (2019, see note 16).

[45] See, for example, L. T. Mselle, K. M. Moland, A. Mvungi, et al., “Why Give Birth in Health Facility? Users’ and Providers’ Accounts of Poor Quality of Birth Care in Tanzania,” BMC Health Services Research 13 (2013); Bintabara et al. (see note 19); A. E. Strong, Documenting Death: Maternal Mortality and the Ethics of Care in Tanzania (University of California Press, 2020).

[46] Hanson et al. (see note 21); Thaddeus and Maine (see note 26); John et al. (see note 24).

[47] John et al. (see note 24); Strong (see note 45).

[48] M. Ali, J. P. Cordero, F. Khan, et al., “Leaving No One Behind: A Scoping Review on the Provision of Sexual and Reproductive Health Care to Nomadic Populations,” BMC Women’s Health 19/161 (2019).

[49] K. Ramsey, I. Mashasi, S. Kujawski, et al., “Hidden in Plain Sight: Validating Theory on How Health Systems Enable the Persistence of Women’s Mistreatment in Childbirth Through a Case in Tanzania,” SSM – Health Systems 3 (2024).

[50] John et al. (see note 24).

[51] Miltenburg et al. (see note 22); Khosla et al. (see note 22).

[52] Ramsey et al. (see note 49).

[53] M. D. Balde, K. Nasiri, H. Mehrtash, “Labour Companionship and Women’s Experiences of Mistreatment During Childbirth: Results from a Multi-Country Community-Based Survey,” BMJ Global Health 5/Suppl 2 (2020).

[54] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 11), para 12(c).

[55] Kruk et al. (see note 23); Dahab and Sakellariou (see note 20); A. McMahon, D. Mohan, A. LeFevre, et al., “‘You Should Go So That Others Can Come’: The Role of Facilities in Determining an Early Departure After Childbirth in Morogoro Region, Tanzania,” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 15/328 (2015).