Harm Reduction Policing: A Scoping Review Examining Police Training as a Strategy to Overcome Barriers to HIV Services

Vol 27/2, 2025, pp. 331-342 PDF

Diederik Lohman, Nina Sun, and Joseph J. Amon

Abstract

Discriminatory laws and punitive policing practices have long been known to impede access to HIV and other health services. While the 2021–2026 Global AIDS Strategy calls for decriminalizing laws targeting key and vulnerable populations, progress toward this goal has largely stalled. To better understand the potential for working with police to ensure access to HIV services, we conducted a scoping review of peer-reviewed and gray literature examining outcomes of police training published between January 2000 and August 2024. Following a review of 639 articles and reports meeting our search criteria, we found 11 peer-reviewed articles and six reports that included outcomes of police training. Our review found that well-designed police training can benefit both law enforcement and communities. It can be a cost-effective public health investment. Best practices for police training included addressing police occupational safety concerns; using trainings as opportunities to build stronger relationships between law enforcement and communities; fostering support from police leadership; and embedding training in a broader effort to change policing. While changing police is complex, our review found a body of literature describing positive outcomes from training, including increasing recognition by police of their role to protect the right to health for key and vulnerable populations.

Introduction

Policing practices have long been shown to have a significant impact on access to HIV prevention, testing, and treatment services for criminalized and highly stigmatized populations.[1] Compelling research has found, for example, clear links between repressive policing and experiences of physical or sexual violence among key populations, which can increase their vulnerability to HIV.[2] Studies have documented policing practices such as confiscation of condoms, arrests and incarceration, and raids and displacement that act as barriers to HIV services for sex workers.[3] Such practices have resulted in both lower condom use and more difficulty negotiating condom use among sex workers.[4] For people who use drugs, research has found negative health outcomes as a result of syringe confiscation by police, and reluctance to carry syringes and rushed injection practices among people who use drugs due to fear of police.[5] Other studies have noted an association between policing and avoidance of harm reduction sites.[6] Criminalization and associated punitive policing practices have also impacted HIV vulnerability among men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women.[7]

To eliminate HIV as a global public health threat by 2030, governments must remove barriers that prevent key populations from accessing or being retained in HIV-related services. In support of this approach, the 2021–2026 Global AIDS Strategy includes a goal on the decriminalization of sex work, same-sex sexual relations, transgender people, and drug use, including targets related to removing punitive laws and reducing stigma and discrimination against key and vulnerable populations.[8] Removing such barriers is also a legal obligation for governments under international human rights law: the right to the highest attainable standard of health, which almost all states are legally bound to uphold, stipulates that states must take the necessary steps for the prevention, treatment, and control of “epidemic, endemic, occupational and other diseases.”[9] This includes a duty to protect people at risk of infectious diseases from policing practices that put their health at risk.

However, despite global goals and human rights obligations, the criminalization of sex work, drug use, and sexual orientation and gender identity persists, bolstered by broad public support.[10] As a result, the policing of drug use, sex work, and sexual orientation/gender identity will likely continue well beyond 2030.

To better understand the potential for changes to policing as a strategy to ensure access to HIV services and the factors that contribute to positive outcomes of police training, we conducted a scoping review examining training outcomes, including both peer-reviewed and gray literature.

Methods

Over the last few decades, there have been numerous efforts to reduce the negative impact of policing on access to HIV and other health services, often initiated by community-led organizations that work closely with key and vulnerable populations. Interventions have included sensitization activities, the development of police-public health partnerships, community engagement, and regulatory reform.[11] A central feature of many of these interventions has been police education or training programs that aim to teach officers who frequently come in contact with key and vulnerable populations about these populations, public health goals, and occupational safety.

To broadly capture these initiatives alongside research studies, we conducted a scoping review of articles published between January 2000 and August 2024 using a modified PRISMA Extension for Scoping Review protocol.[12] We conducted three different searches in PubMed for each of the three key populations most commonly impacted by policing: people who use drugs, sex workers, and LGBTQ populations. Search terms included combinations of terms such as “police education” or “police training” or “law enforcement training” to identify articles related to police training; “substance use” or “drug use” or “people who use drugs” or “people who inject drugs” or “drug abuse” or “drug user” to identify articles addressing people who use drugs (and similar terms for LGBTQ populations and for sex workers); and terms such as “HIV” or “AIDS” or “hepatitis C” or “dependence” or “addiction” to examine specific outcomes. (See Appendix for more specific search details.)

All articles that substantively focused on HIV and police education or training programs and that described program outcomes were included. Articles that focused only on the impact of policing on HIV and key populations were excluded.

All articles were reviewed independently by two researchers, and information on outcomes and potential training best practices were noted. Researchers compared results and resolved any disparities through a reexamination of the article to ensure consensus and consistency with the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Gray literature was identified through a review of websites of donors and implementing organizations working on this topic; through requests to public health professionals working in international organizations related to HIV and key and vulnerable populations; and by examining citations among peer-reviewed and gray literature for further sources.

Results

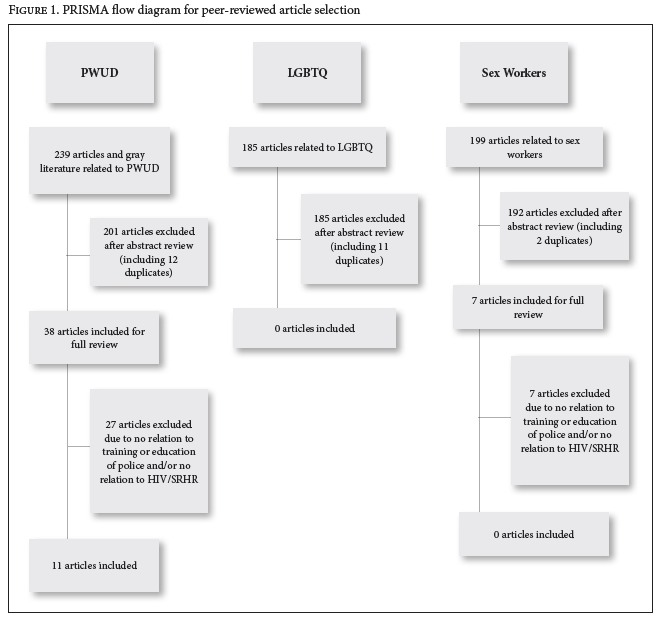

Our initial search yielded a total of 623 peer-reviewed articles and 16 gray literature reports. For the peer-reviewed articles, after we removed duplicates and conducted title and abstract reviews, 45 unique publications remained. A full review of these articles found that 11 articles contained data related to key outcomes (Figure 1). Of the 16 gray literature reports initially identified, six reports met the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

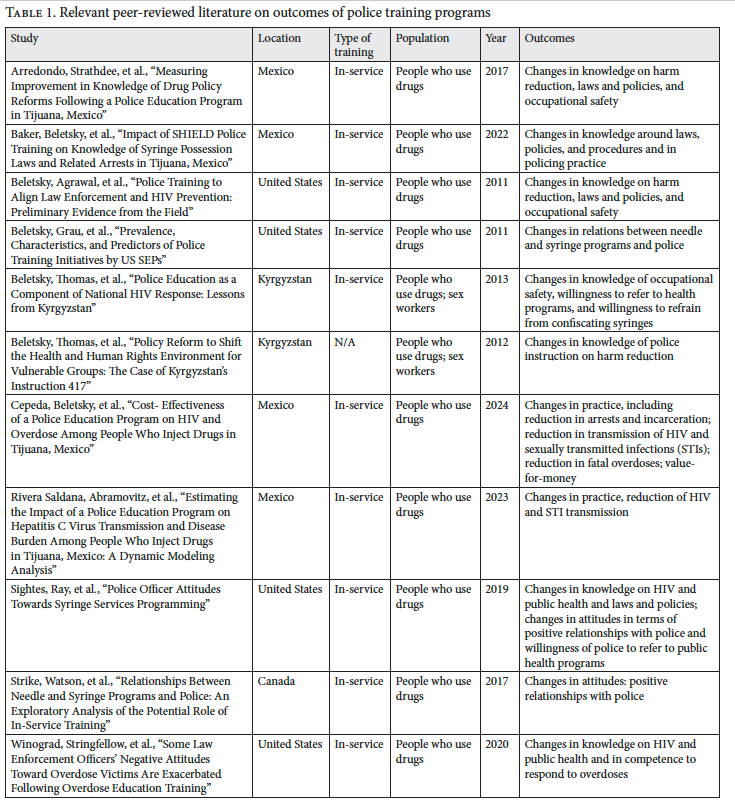

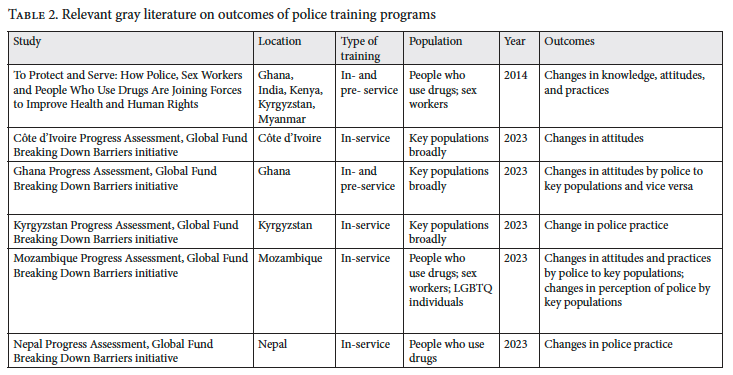

All of the peer-reviewed articles identified focused on police training programs for people who use drugs and sex workers; none concerned MSM or transgender populations (Table 1). In the gray literature, we identified six other publications, five which were published as a part of evaluation studies of countries participating in the Global Fund’s Breaking Down Barriers initiative and one by the Open Society Foundations (OSF) (Table 2).

Key findings from the studies included how police training programs are conducted and what outcomes of police training are reported, including changes in knowledge, attitudes, and practices, as well as health outcomes and studies of cost-effectiveness. The results of the review are summarized by theme.

How police education programs are conducted

Our review identified a broad diversity in the focus and objectives of police training interventions implemented between 2011 and 2023. Notably, articles on police training published in peer-reviewed literature almost always addressed people who use drugs, while those identified from the gray literature included a broader range of populations, including people who use drugs, sex workers, and LGBTQ populations. Most programs were conducted for active police officers (in-service training); however, training in Ghana, Kenya, and Senegal described combinations of pre-service training (institutionalized through police academies) and in-service police education programs.[13]

While most of the police education programs were established as part of programming to reduce the impact of HIV among key populations, a few were also implemented as part of overdose prevention programming.[14] Most police education programs combined a variety of training topics, including information about HIV, hepatitis C, drug treatment, and overdose prevention; harm reduction programs; laws and policies related to HIV, harm reduction, drug use, and sex work; and occupational safety issues relevant to police, such as avoiding accidental needle pricks. Multiple police training programs described in the gray literature also provided general information about human rights norms and the rights of key and vulnerable populations.[15] By contrast, none of the peer-reviewed studies mentioned attention to human rights. Where these trainings mentioned a focus on law and policy, the focus appeared to be a narrow one on legal provisions such as regulating syringe access or establishing thresholds for criminal liability for possession of drugs.[16]

Peer-reviewed and gray literature reports on police training programs found similar outcomes, including positive changes in knowledge related to harm reduction, relevant laws and policies, and occupational safety practices. Less commonly reported outcomes included changes in relations between needle and syringe programs (NSPs) and police; willingness to refer people who use drugs to health programs and willingness to refrain from confiscating syringes; and changes in practices, including reduction in arrests and incarceration, reduction in transmission of HIV and STIs, and reduction in fatal overdoses. Some studies also calculated the value-for-money of training programs.

While most of the peer-reviewed studies reported positive outcomes of police education programs, in some cases the magnitude of change was modest. Among the gray literature, evaluations and case studies all reported positive changes. Yet sample sizes were often too small to allow for generalization, and outcomes were sometimes mixed or modest. In both cases, interventions were often implemented on too small a scale and for too little time to reach a critical mass and generate sufficient momentum to effect long-term change in policing practices and overcome a deeply ingrained distrust of police—and government authorities more generally—among key and vulnerable populations.

Changes in knowledge

Several peer-reviewed articles found that knowledge of participating police officers about HIV, public health interventions, legal standards and processes, and occupational safety had increased among training participants. For example, two studies that examined a police training program (Project SHIELD) in Tijuana, Mexico, found an improvement in officers’ knowledge about drug policy and the law around harm reduction, including significant improvements in conceptual and technical understanding of laws around syringe and drug possession.[17] One of the studies showed that improved knowledge about syringe possession laws was sustained over a period of two years.[18] Another study on police officer training in Rhode Island, United States, found that training focused on the rationale of public health programs, occupational safety, and laws and regulations around law enforcement resulted in modestly better understanding of HIV risk from needlestick injuries, as well as increased knowledge about the law around syringe possession.[19] A study assessing the impact of a comprehensive overdose education and naloxone distribution training found significant increases in knowledge and self-reported competence to respond to an overdose situation.[20]

While the Breaking Down Barriers initiative assessments and case studies did not specifically report on changes in knowledge (with the exception of a case study from Kenya), they did report on other outcomes that undoubtedly relied on changes in knowledge.[21]

Changes in attitudes

Some peer-reviewed studies and evaluations also looked at changes in the attitudes of training participants, demonstrating, among others, that police officers who undergo training programs expressed greater willingness to help people who use drugs and refer people to safe syringe and harm reduction programs.[22]

The Côte d’Ivoire progress assessment reported changes in attitudes through a small survey among past participants of the Looking In, Looking Out (LILO) training program that focuses on reducing prejudice toward key populations. Since 2015, some 700 health workers, law enforcement officers, social workers, and religious leaders have attended.[23] Survey participants, including law enforcement officers, overwhelmingly reported that the training had significantly or very significantly changed their attitudes and professional approach toward key populations. One police officer noted that following the LILO training, “I’m more caring and attentive to [key populations’] concerns.” In the Mozambique assessment, the Mozambique Republic Police, which provides training for officers on issues related to key populations (including HIV, human rights, and harm reduction), reported several attitudinal changes linked to the trainings, such as more welcoming attitudes of police management and officers toward key populations, including reports of MSM and transgender people becoming police officers; increases in the number of complaints about violations key populations filed with the police; and police officers taking reports of violence against key populations more seriously, even in cases where the police themselves are perpetrators.[24]

Four of the six case studies in the OSF publication also reported improved attitudes among police officers following training interventions.[25] For example, the Kenya and Ghana case studies reported a more welcoming attitude toward key populations, and the Kyrgyzstan case study noted increased willingness of police officers to refer people who use drugs to harm reduction programs.

Surprisingly, one peer-reviewed study that looked at outcomes of an overdose education intervention found that while attitudes of most officers toward people facing overdose had improved after the training, a significant minority of officers reported more negative attitudes toward them post-training. The study recommended experimentation with different training approaches to better understand these results.[26]

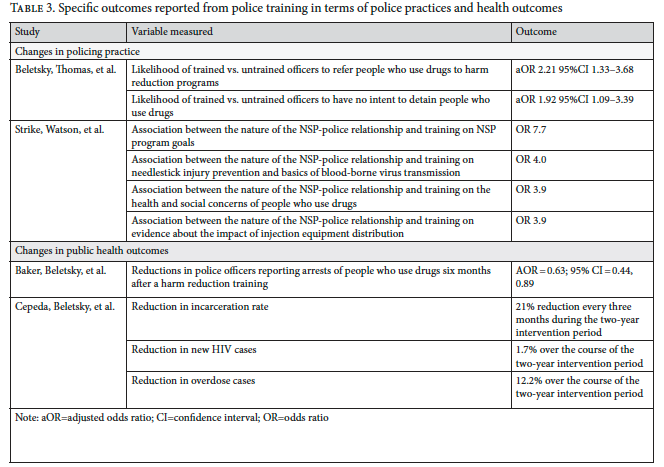

Changes in practice

Several studies looked at changes in policing practice following training interventions. A study in Canada, for example, found a positive association between, on the one hand, good relationships between NSPs and police departments and, on the other, in-service training of police on NSP goals and harm reduction.[27] A survey of syringe exchange providers in the United States found that these providers saw police training as key to improving their relationship with police.[28] Another study found that correct knowledge related to HIV, the law, and injection drug use was associated with significantly lower odds of reporting arrests among people who use drugs.[29]

The gray literature contains anecdotal evidence of improved policing practices toward key and vulnerable populations. In the Nepal assessment report, for example, sex worker-led organizations noted that when sex workers are arrested, trained police officers will often engage with local community-based organizations representing sex workers, facilitating their release without charges.[30] In Côte d’Ivoire, key population-led organizations mentioned that law enforcement officers who had gone through the LILO training played a key role in helping them respond effectively to cases of gender-based violence, detention, and harassment against members of key populations.[31] The OSF case study and the Breaking Down Barriers initiative assessment report on Kyrgyzstan similarly reported that institutionalized police training, in combination with progressive legal changes, had resulted in a positive impact on policing practices, including better relationships between police and key populations, with some civil society groups reporting a decrease in the number of outreach workers detained by police.[32]

Changes in public health outcomes

A small number of studies examined the impact of police education programs on public health outcomes. These studies found reductions in HIV and other STI cases following police education interventions, reporting reductions in incarceration and, as a result, decreased HIV incidence and a decrease in overdoses as compared to pre-training trends (Table 3).[33] Although the authors characterize the impact of police training on HIV transmission (1.7% over the course of the two-year intervention period) and overdose (12.2% over the course of the two-year intervention period) as modest, this finding is notable. Relatedly, one finding from Project SHIELD in Tijuana found that police training could reduce the incidence of hepatitis C among people who use drugs.[34]

Cost-effectiveness

One consideration for donors in investing in police training efforts is the cost-effectiveness of such approaches. Javier Cepeda et al. conducted a value-for-money analysis of the police training programs against incarceration and health care costs, concluding that Project SHIELD was cost-effective: the program cost US$3,746 for every disability-adjusted life year averted, well below the recommended willingness-to-pay threshold for Mexico (US$8,347 in 2020).[35]

Discussion

As donors consider investing in more work with law enforcement, it is essential to build on best practices that have emerged from the two-plus decades of previous work. Peer-reviewed and gray literature identify a variety of lessons learned, outlined below, to strengthen the effectiveness of police training programs.

Addressing police concerns

Ensuring that police training sessions appeal to participants strengthens officer engagement. The OSF publication notes that “successful reform of police practice toward these groups must … identify incentives or ways of framing engagement to show that these efforts can help police protect themselves and do their jobs.”[36] Reflecting earlier research findings, several publications argue for addressing occupational safety and avoiding needlestick incidents to engage officers in the trainings, with one noting that “training that combines occupational safety with syringe access content can help align law enforcement with public health goals.”[37] The Kenya case study found that police were interested in developing better relationships with sex workers because information from them might prevent serious crime or assist in investigations.[38]

Involving and building relationships with affected communities

Several publications discuss the importance of not only involving key populations in trainings of police officers but also building stronger relationships between law enforcement and communities beyond specific training programs. The OSF publication notes that “police knowledge of criminalized groups is often shaped by the same stereotypes and moral judgments that are prevalent in society more generally. It has proven critical to train law enforcement about the realities of the lives of sex workers and people who use drugs.”[39] The Ghana case study notes that “a key component in shifting police attitudes toward sex workers in Ghana was sex workers themselves speaking in these trainings of the impact that police repression and abuse had on their lives.”[40]

Several Breaking Down Barriers initiative assessments argue for routine, direct engagement between police and impacted communities through community-police partnerships or dialogues.[41] Côte d’Ivoire’s LILO trainings, which are part of a broader effort to empower community members to defend their rights through community paralegals, have created lasting relationships between police officials and community actors that have repeatedly helped end or address abuses against community members.[42]

Fostering ownership and support from police leadership

Engaging with law enforcement institutions that do not see health care access as core to their functions is a significant challenge to successful, long-term police training programs. Especially when trainings are organized by civil society organizations, law enforcement agencies’ commitment to and ownership of such trainings may be lacking.[43] Several publications therefore emphasize the importance of ensuring support from police leadership.[44] For example, the OSF publication notes, “Given the hierarchical nature of law enforcement, it has been essential to secure the endorsement of police leadership for changing police practices toward sex workers and people who use drugs, and to get them to communicate this shift to less senior officers.”[45]

Institutionalizing police training

Police training needs to be an ongoing intervention; one-off trainings have little impact because of, among other things, high turnover in police forces.[46] These trainings should be institutionalized with sustained resources and the routine training of officers and new recruits. Institutionalization can also help address the challenge of scaling up training.[47]

Studying and routinely evaluating police training programs

There is an urgent need for more peer-reviewed studies and robust, formal evaluations of police education programs. The dearth of such studies and evaluations is one of the reasons for the limited evidence base. Of the 15 progress assessments that discuss police training interventions, only five report key outcomes. Not a single police training intervention funded through the Breaking Down Barriers initiative has been formally evaluated. The same is largely true for US interventions: discussing a survey of syringe exchange programs in the United States about police trainings, Leo Beletsky, Lauretta Grau, et al., note that “only four [of 21] programs [that had conducted police trainings] reported having a formal evaluation component as part of their training; to date, none has been published.”[48] Funders and program implementers should commission evaluations of police trainings to address the dearth of evidence.

Embedding training in a broader effort to change policing

Many of the police training interventions described in the literature were part of a broader set of interventions. In Tijuana, Mexico, for example, police trainings were held as part of an effort to facilitate the rollout of a policy change.[49] They helped bring about a dramatic increase in participants’ technical and conceptual legal knowledge and awareness of human rights norms related to decriminalization for marijuana, heroin, and methamphetamine, as well as the legality of syringe possession. Other publications note that police training alone is often insufficient to sustain changes in policing. For example, Leo Beletsky, Alpna Agrawal, et al. argue that “management and peer-driven interventions, such as those incentivizing police and public health collaboration and censuring unauthorized syringe confiscation and other practices that run counter to public health goals, may be needed to reinforce training messages and shift entrenched attitudes.”[50] Thus, police trainings should be part of a broader strategy aimed at removing policing as a barrier to HIV services for key populations.

Conclusion

Changing the culture of police forces and the constraints of legal and political environments in settings that criminalize key populations is not a simple task, and investment in programs to accomplish this has, for reasons that are not entirely clear, been insufficient. Nevertheless, for more than two decades, a growing body of literature has been advocating for and describing such programs. While the literature reporting on the outcomes of these interventions is still limited, it does provide some indication of best practices, what has not worked, and what may be promising strategies to address abusive policing. More research is needed, especially to expand the range of countries and populations studied. Currently, the peer-reviewed literature is narrowly focused on Mexico and people who use drugs. It is likely that police forces will question the validity of the results of police training in one country compared to the specific characteristics and political environment they face in another.

Nonetheless, the evidence from our review shows that well-designed police training can have benefits for both law enforcement and communities and can be a cost-effective public health investment. Importantly, training law enforcement on the control of infectious disease and the rights of populations at increased risk of contracting HIV also allows countries to fulfill their legal obligation to protect the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.[51]

With 2030 rapidly approaching, investing in programs that can reduce the negative impact of policing on access to HIV services for criminalized populations, along with more pointed research and evaluations of such police engagement programs, is essential. Taking this public health approach to policing requires scaling up programs and policies to change the social norms and punitive approaches that law enforcement institutions use in their engagement with key populations. It is not until there is sufficient, sustained investment in such work that the world will truly reach the last mile for key populations within the HIV response.

Diederik Lohman, MSPH, MA, is an independent consultant, Maplewood, United States.

Nina Sun, JD, is principal consultant at Article XII, North Carolina, United States.

Joseph J. Amon, MSPH, PhD, is Desmond M. Tutu Professor in Public Health and Human Rights, director of the Center for Public Health and Human Rights, and a distinguished professor of the practice in the Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, United States, and editor-in-chief of Health and Human Rights.

Please address correspondence to Diederik Lohman. Email: diederiklohman@gmail.com.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2025 Lohman, Sun, and Amon. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Appendix

| Search terms | |||

| Population | Search 1 | Search 2 | Search 3 |

| People who use drugs | (“police education” OR “police training” OR “law enforcement training”) AND (“substance use” OR “drug use” OR “people who use drugs” OR “people who inject drugs” OR “drug abuse” OR “drug user”) | (“police education” OR “police training” OR “law enforcement training” OR “policing”) AND (“substance use” OR “drug use” OR “people who use drugs” OR “people who inject drugs” OR “drug abuse” OR “drug user”) AND (“HIV” OR “AIDS” OR “hepatitis C” OR “dependence” OR “addiction”) | (“police education” OR “police training” OR “law enforcement training” OR “policing”) AND (“substance use” OR “drug use” OR “people who use drugs” OR “people who inject drugs” OR “drug abuse” OR “drug user”) |

| LGBTQ | (“police education” OR “police training” OR “law enforcement training”) AND (“LGBTQ” OR “sexual orientation” OR “gender identity” OR “SOGIE” OR “MSM” OR “trans*” OR “homosexual” OR “gay”) | (“police education” OR “police training” OR “law enforcement training”) AND (“LGBTQ” OR “sexual orientation” OR “gender identity” OR “SOGIE” OR “MSM” OR “trans*” OR “homosexual” OR “gay”) AND (“HIV” OR “AIDS” OR “hepatitis C” OR “addiction” or “dependence”) | (“police education” OR “police training” OR “law enforcement training” OR “policing”) AND (“LGBTQ” OR “sexual orientation” OR “gender identity” OR “SOGIE” OR “MSM” OR “trans*” OR “homosexual” OR “gay”) AND (“HIV” OR “AIDS” OR “hepatitis C” OR “addiction” or “dependence”) |

| Sex workers | (“police training” OR “law enforcement training” OR “policing”) AND (“sex work” OR “sex workers” OR “sell sex”) | (“police education” OR “police training” OR “law enforcement training” OR “policing”) AND (“criminal” OR “criminalized”) AND (“sex work” OR “sex workers” OR “sell sex”) | (“police education” OR “police training” OR “law enforcement training” OR “policing”) AND (“sex work” OR “sex workers” OR “sell sex”) |

References

[1] P. Baker, L. Beletsky, L. Avalos, et al., “Policing Practices and Risk of HIV Infection Among People Who Inject Drugs,” Epidemiologic Reviews 42/1 (2020); K. H. Footer, B. E. Silberzahn, K. N. Tormohlen, and S.G. Sherman, “Policing Practices as a Structural Determinant for HIV Among Sex Workers: A Systematic Review of Empirical Findings,” Journal of the International AIDS Society 19/4 S3 (2016); S. Acharya, M. R. Parthasarathy, V. Karanjkar, et al., “Barriers and Facilitators for Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy, and Strategies to Address the Barriers in Key Populations, Mumbai: A Qualitative Study,” PLOS One 19/7 (2024).

[2] L. Platt, P. Grenfell, R. Meiksin, et al., “Associations Between Sex Work Laws and Sex Workers’ Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Quantitative and Qualitative Studies,” PLOS Medicine 15/12 (2018); K. Shannon, S. A. Strathdee, S. M. Goldenberg, et al., “Global Epidemiology of HIV Among Female Sex Workers: Influence of Structural Determinants,” Lancet 385/9962 (2015).

[3] Shannon et al. (2015, see note 2); M. A. Pando, R. S. Coloccini, E. Reynaga, et al., “Violence as a Barrier for HIV Prevention Among Female Sex Workers in Argentina,” PLOS One 8/1 (2013); J. T. Erausquin, E. Reed, and K. M. Blankenship, “Police-Related Experiences and HIV Risk Among Female Sex Workers in Andhra Pradesh, India,” Journal of Infectious Diseases 1/204(Suppl 5) (2011); S. L. Braunstein, C. M. Ingabire, E. Geubbels, et al., “High Burden of Prevalent and Recently Acquired HIV Among Female Sex Workers and Female HIV Voluntary Testing Center Clients in Kigali, Rwanda,” PLOS One 6/9 (2011); C. Zhang, X. Li, Y. Hong, et al., “Unprotected Sex with Their Clients Among Low-Paying Female Sex Workers in Southwest China,” AIDS Care 25/4 (2013); M. R. Decker, A. L. Crago, S. K. H. Chu, et al., “Human Rights Violations Against Sex Workers: Burden and Effect on HIV,” Lancet 385/9963 (2015).

[4] Erausquin et al. (see note 3); D. K. Mbote, L. Nyblade, C. Kemunto, et al., “Police Discrimination, Misconduct, and Stigmatization of Female Sex Workers in Kenya: Associations with Delayed and Avoided Health Care Utilization and Lower Consistent Condom Use,” Health and Human Rights 22/2 (2020); K. Shannon, S. A. Strathdee, J. Shoveller, et al., “Structural and Environmental Barriers to Condom Use Negotiation with Clients Among Female Sex Workers: Implications for HIV-Prevention Strategies and Policy,” American Journal of Public Health 99/4 (2009).

[5] S.A. Strathdee, R. Lozada, G. Martinez, et al., “Social and Structural Factors Associated with HIV Infection Among Female Sex Workers Who Inject Drugs in the Mexico-US Border Region,” PLOS One 6/4 (2011); L. Beletsky, R. Lozada, T. Gaines, et al., “Syringe Confiscation as an HIV Risk Factor: The Public Health Implications of Arbitrary Policing in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico,” Journal of Urban Health 90/2 (2013); R. E. Booth, S. Dvoryak, M. Sung-Joon, et al., “Law Enforcement Practices Associated with HIV Infection Among Injection Drug Users in Odessa, Ukraine,” AIDS and Behavior 17/8 (2013).

[6] Baker et al. (2020, see note 1).

[7] C. H. Logie, A. Lacombe-Duncan, K. S. Kenny, et al., “Associations Between Police Harassment and HIV Vulnerabilities Among Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender Women in Jamaica,” Health and Human Rights 19/2 (2017); D. H. Li, S. Rawat, J. Rhoton, et al., “Harassment and Violence Among Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) and Hijras After Reinstatement of India’s ‘Sodomy Law,’” Sexuality Research and Social Policy 14/3(2017); S. Bano, R. Rahat, and F. Fischer, “Inconsistent Condom Use for Prevention of HIV/STIs Among Street-Based Transgender Sex Workers in Lahore, Pakistan: Socio-Ecological Analysis Based on a Qualitative Study,” BMC Public Health 23/635 (2023).

[8] UNAIDS, Global AIDS Strategy 2021–2026: End Inequalities. End AIDS (2025).

[9] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI) (1966); Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000), para. 12(b)(iii).

[10] UNAIDS, 2024 Global AIDS Update: The Urgency of Now; AIDS at a Crossroads (2024).

[11] Open Society Foundations, To Protect and Serve: How Police, Sex Workers, and People Who Use Drugs Are Joining Forces to Improve Health and Human Rights (2014); L. Beletsky, R. Thomas, M. Smelyanskaya, et al., “Policy Reform to Shift the Health and Human Rights Environment for Vulnerable Groups: The Case of Kyrgyzstan’s Instruction 417,” Health and Human Rights 12/14 (2012).

[12] A. C. Tricco, E. Lillie, W. Zarin, et al., “PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation,” Annals of Internal Medicine 169/7 (2018).

[13] N. Sun, R. Armstrong, and B. Dornoo, Ghana Progress Assessment (Global Fund, 2023); M. Clayton and S. Masasabi, Kenya Progress Assessment (Global Fund, 2023); C. Kazatchkine, C. Tshimbalanga, and D. Sow, Senegal Progress Assessment (Global Fund, 2023).

[14] R. P. Winograd, E. J. Stringfellow, S. K. Phillips, and C. A. Wood, “Some Law Enforcement Officers’ Negative Attitudes Toward Overdose Victims Are Exacerbated Following Overdose Education Training,” American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 46/5 (2020); J. Arredondo, S. A. Strathdee, J. Cepeda, et al., ”Measuring Improvement in Knowledge of Drug Policy Reforms Following a Police Education Program in Tijuana, Mexico,” Harm Reduction Journal 14/72 (2017).

[15] Open Society Foundations (see note 11); Sun et al., Ghana Progress Assessment (see note 13).

[16] Winograd et al. (see note 14); Arredondo et al. (see note 14); L. Beletsky, A. Agrawal, B. Moreau, et al., “Police Training to Align Law Enforcement and HIV Prevention: Preliminary Evidence from the Field,” American Journal of Public Health 101/11 (2011); J. Cepeda, L. Beletsky, D. Abramovitz, et al., “Cost-Effectiveness of a Police Education Program on HIV and Overdose Among People Who Inject Drugs in Tijuana, Mexico,” Lancet Regional Health – Americas 30/100678 (2024); E. Sightes, B. Ray, S. R. Paquet, et al., “Police Officer Attitudes Towards Syringe Services Programming,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 205/1 (2019).

[17] Arredondo (see note 14); P. Baker, L. Beletsky, R. Garfein, et al., “Impact of SHIELD Police Training on Knowledge of Syringe Possession Laws and Related Arrests in Tijuana, Mexico,” American Journal of Public Health 112/6 (2022).

[18] Baker et al. (2022, see note 17).

[19] Beletsky et al., “Police Training” (see note 16).

[20] Winograd et al. (see note 14).

[21] Open Society Foundations (see note 11).

[22] L. Beletsky, R. Thomas, N. Shumskaya, et al., “Police Education as a Component of National HIV Response: Lessons from Kyrgyzstan,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 32/Suppl 1 (2013); C. D. Rivera Saldana, D. Abramovitz, L. Beletsky, et al., “Estimating the Impact of a Police Education Program on Hepatitis C Virus Transmission and Disease Burden Among People Who Inject Drugs in Tijuana, Mexico: A Dynamic Modeling Analysis,” Addiction 118/9 (2023).

[23] J. Papy, C. Tshimbalanga, and D. Lohman, Cote d’Ivoire Progress Assessment (Global Fund, 2023).

[24] M. Clayton, C. Grant, and A. Mandlate, Mozambique Progress Assessment (Global Fund, 2023).

[25] Open Society Foundations (see note 11).

[26] Winograd et al. (see note 14).

[27] C. Strike and T. M. Watson, “Relationships Between Needle and Syringe Programs and Police: An Exploratory Analysis of the Potential Role of In-Service Training,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 175/1 (2017).

[28] L. Beletsky, L. E. Grau, E. White, et al., “Prevalence, Characteristics, and Predictors of Police Training Initiatives by US SEPs,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 119/1–2 (2011).

[29] Baker et al. (2022, see note 17); Cepeda et al. (see note 16).

[30] N. Sun, K. Kaplan, and S. Neupane, Nepal Progress Assessment (Global Fund, 2023).

[31] Papy et al. (see note 23).

[32] Open Society Foundations (see note 11).

[33] Cepeda et al. (see note 16); Rivera Saldana et al. (see note 22).

[34] Rivera Saldana et al. (2022, see note 22).

[35] Cepeda et al. (see note 16).

[36] Open Society Foundations (see note 11).

[37] Beletsky et al., “Police Training” (see note 16); Open Society Foundations (see note 11); Arredondo et al. (see note 14); C. S. Davis and L. Beletsky, “Bundling Occupational Safety with Harm Reduction Information as a Feasible Method for Improving Police Receptiveness to Syringe Access Programs: Evidence from Three U.S. cities,” Harm Reduction Journal 6/16 (2009).

[38] Open Society Foundations (see note 11).

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid.

[41] M. Golichenko and D. Lohman, Kyrgyzstan Progress Assessment (Global Fund, 2023); Clayton et al. (see note 24); South Africa Progress Assessment (2023); M. McLemore, J. Amon, C. Narcisse, and A. Perkins, Jamaica Progress Assessment (Global Fund, 2023); J. Csete, M. Clayton, and P. Chibatamoto, Botswana Progress Assessment (Global Fund, 2023); D. Lohman, J. Amon, and M. B. Doussoh, Benin Progress Assessment (Global Fund, 2023); R. Armstrong, M. Muwonge, F. Obua, et al., Uganda Progress Assessment (Global Fund, 2023).

[42] Papy et al. (see note 23).

[43] Csete et al. (see note 41); Lohman et al., Benin Progress Assessment (see note 41); Armstrong et al. (see note 41).

[44] Sun et al., Ghana Progress Assessment (see note 13); Clayton and Masasabi (see note 13); Lohman et al., Benin Progress Assessment (see note 41).

[45] Open Society Foundations (see note 11).

[46] South Africa Progress Assessment (see note 41); Golichenko and Lohman (see note 41); Clayton et al. (see note 24); McLemore et al. (see note 41); D. Lohman, E. Kononchuk, J. Amon, Ukraine Progress Assessment (Global Fund, 2023).

[47] Sun et al., Ghana Progress Assessment (see note 13); Papy et al. (see note 23); Sun et al., Nepal Progress Assessment (see note 30); South Africa Progress Assessment (see note 40); Lohman et al., Benin Progress Assessment (see note 41); N. Sun, M. McLemore, and C. Aquino, Philippines Progress Assessment (Global Fund, 2023); Lohman et al., Ukraine Progress Assessment (see note 46).

[48] Beletsky et al., “Prevalence, Characteristics, and Predictors” (see note 28).

[49] Arredondo et al. (see note 14).

[50] Beletsky et al., “Police Training” (see note 16).

[51] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see note 9).