A Narrative Review of Dual Loyalty Conflicts in Custodial Settings and Implications for Community Practice

Vol 27/2, 2025, pp. 375-391 PDF

Michelle Suh, Marc David Robinson, and Holland Kaplan

Abstract

Dual loyalty dilemmas are conflicts between health care professionals’ obligations toward their patients and third-party interests. These conflicts are more common and starker in custodial settings, such as jails and prisons, military detention facilities, immigration detention centers, and involuntary psychiatric institutions. Despite encountering patients in custody, health care professionals (HCPs) in community settings have limited knowledge and training. In this narrative review, we examined dual loyalty conflicts faced by HCPs working in custodial settings and then applied the identified themes to community-based hospitals where HCPs care for patients in custody. We searched databases for original papers relating to patients in custody and dual loyalties and then abstracted key themes, findings, and characteristics of the conflicts. There are five categories of competing loyalties that give rise to dual loyalty conflicts: institutional and organizational entities, legal and regulatory guidelines, ethical and moral responsibilities, social and public responsibilities, and other individuals. Themes include the inappropriate withholding or delaying of care, the provision of intervention despite patient refusal, the violation of patients’ rights to privacy, cruel non-clinical interventions (e.g., torture), and the failure to document or report information accurately. Mitigation strategies in the literature emphasize expanding human rights education, improving patient communication around possible conflicts, and raising clinician awareness of institutional policies. Common in the care of patients in custodial settings worldwide, dual loyalty conflicts can impact patient care. However, pursuing mitigation strategies can lessen their impact.

Case study

A hospitalist at a large urban medical center is caring for a 52-year-old incarcerated man transferred from the county jail with sepsis due to an infected diabetic foot ulcer. Two uniformed correctional officers are permanently stationed outside his hospital room, restricting his movement and monitoring his interactions with staff. When the hospitalist attempts to conduct a private physical examination, one of the officers insists on remaining in the room, citing security protocols. The patient looks visibly distressed and withdraws from further discussion. The hospitalist asks the officer if he can remove the patient’s ankle shackles to enable a complete assessment. The officer declines, again citing security protocols. Later, the hospitalist documents incomplete findings in the medical record, noting limited access to the patient for an adequate assessment. In the afternoon, a prison administrator calls the hospitalist, requesting updates on the patient’s condition and estimated discharge date. A hospital administrator asks whether the hospitalist could expedite discharge to the jail infirmary due to limited bed space in the hospital.

Introduction

Dual loyalty dilemmas arise when health care professionals (HCPs), defined as anyone involved in the care of a patient, experience conflicts between their ethical obligations toward their patients and competing responsibilities to third parties.[1] These conflicts are particularly pronounced in custodial settings, such as military combat zones, military or government detention facilities, immigration detention centers, involuntary psychiatric institutions, and jails or prisons. The existing literature has extensively described dual loyalty conflicts among HCPs working directly within these custodial settings. However, there is limited application of dual loyalty frameworks to community HCPs caring for patients in custody in traditional, non-custodial hospital settings. On-site medical services at correctional facilities are typically limited to primary care, and incarcerated patients requiring emergent or specialty care are transferred to community hospitals. In the United States, more than 730,000 incarcerated adults receive care in community hospitals annually, often under the custodial supervision of correctional officers and with institutional policies that may inadvertently contribute to dual loyalty conflicts.[2] Community HCPs often lack formal training to address the unique challenges that arise when balancing the needs of patients in custody against institutional or legal demands.[3] Unfortunately, there are few clinical guidelines surrounding the care of in-custody patients in traditional, non-custodial hospitals.[4]

This paper adopts a two-part approach. First, we present the results of a narrative review of dual loyalty conflicts faced by HCPs working in custodial settings. Second, we apply the identified themes to a related but underexamined context: community-based hospitals where HCPs care for patients in custody. Although structurally distinct, both settings feature hierarchical structures of authority, security oversight, and limitations in patients’ freedom that give rise to similar dual loyalty conflicts. Finally, we propose mitigation strategies tailored to the unique nature of dual loyalty conflicts experienced by community HCPs in non-custodial, traditional hospitals.

Some dual loyalty scenarios, such as those that involve favoring third-party competing interests in the interest of distributive justice, are considered ethically supportable and arise from duties to promote fairness across populations. However, this paper focuses on dual loyalty conflicts that emerge from external pressures that may compromise patient care. These frameworks share a structural similarity of focusing on competing obligations. However, there is a distinction in the moral stakes. While distributive justice reflects principled ethical prioritization, many custodial dual loyalty conflicts result from external demands contradicting principles of patient-centered care.

Methods

Search strategy

A qualitative literature review was conducted to identify and categorize instances of dual loyalty conflicts among HCPs practicing within custodial settings. We searched PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase for peer-reviewed, English-language, original studies published up to February 20, 2024. We used free-text terms such as “dual loyalties,” “physician,” “jail,” “prison,” and “correctional facilities.”

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Search results were uploaded into Covidence for deduplication and screening. Two independent reviewers evaluated each article for inclusion in the analysis, with discrepancies resolved by consensus via discussion with a third reviewer.

Articles were included if they (1) described dual loyalty conflicts where HCPs faced tensions between patient care obligations and third-party interests, (2) focused on HCPs practicing directly in custodial settings, including military combat zones, government or military detention centers, immigration enforcement facilities, inpatient psychiatric units, and jails or prisons, and (3) provided empirical data, case studies, or normative ethical analyses of dual loyalty conflicts.

Articles were excluded from analysis if they (1) focused on dual loyalty conflicts in health care without discussing custodial settings or (2) addressed health care in custodial settings without specific references to dual loyalty conflicts.

Data extraction

A structured, four-tiered data extraction framework was developed to systematically identify and categorize data. This framework enabled consistent coding and thematic synthesis across diverse sources that included empirical studies, case reports, ethical analyses, legal discussions, and policy documents. The framework included identifying the following within included papers: (1) competing objects of loyalty that are not the patient and patient’s interests, (2) contexts in which dual loyalty conflicts occurred with examples, (3) themes describing the nature of dual loyalty conflicts, and (4) mitigation strategies for dual loyalty conflicts. Dual loyalty conflicts were explicitly described as dual loyalty conflicts by article authors or inferred by reviewers based on discussion of conflicting obligations. Each article was coded for content across these four dimensions by two independent reviewers, with key excerpts extracted verbatim where applicable. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus via discussion with a third reviewer.

Thematic analysis and categorization

The extracted data underwent inductive and thematic analysis. Two independent reviewers coded studies, with discrepancies resolved through consensus discussion. To ensure consistency, codes were iteratively refined, consolidating overlapping themes. Coded excerpts were cross-checked with existing ethical and legal frameworks, including international human rights law, professional medical ethics guidelines, and institutional policies. Extracted themes were organized into a narrative synthesis.

While our literature review is limited to studies addressing custodial contexts, we incorporate additional references into the discussion to contextualize the application of these findings to non-custodial settings. These references were not included in the formal review process but serve to bridge thematic insights into clinical environments where HCPs may encounter patients in custody in traditional, non-custodial hospitals.

Results

Our initial search returned 639 studies, of which 63 met inclusion criteria and were abstracted for analysis. These studies provided insights into the competing objects of loyalty influencing HCPs, contexts of dual loyalty conflicts, thematic categories of dual loyalty dilemmas faced by HCPs in custodial settings, and proposed mitigation strategies for dual loyalty conflicts.

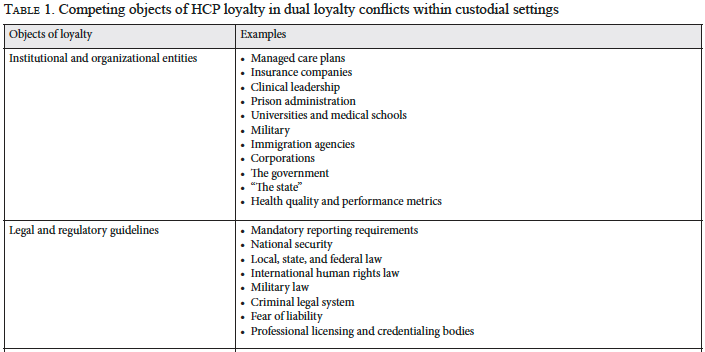

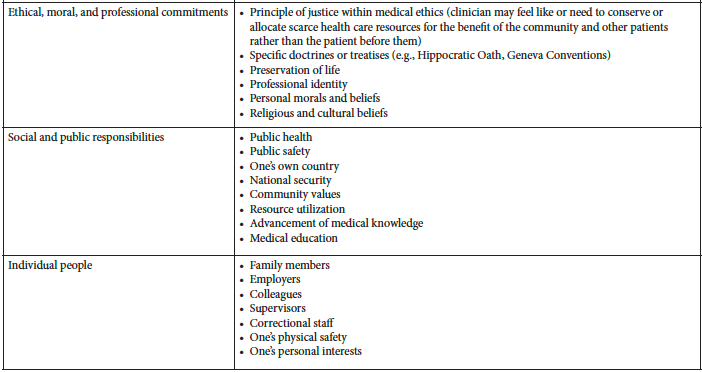

Competing objects of HCP loyalty in dual loyalty conflicts in custodial settings

HCPs practicing in custodial settings face obligations to many competing objects, including institutional and organizational entities; legal and regulatory guidelines; ethical, moral, and professional responsibilities; social and public responsibilities; and individual people. As shown in Table 1, institutions such as hospitals, military organizations, and immigration agencies shape medical decision-making through policies and administrative pressures. Legal requirements, such as mandatory reporting laws and national security considerations, may also create dual loyalty conflicts. Professional commitments, personal morals, and broader societal responsibilities, such as public safety and resource allocation, also complicate dual loyalty dynamics.

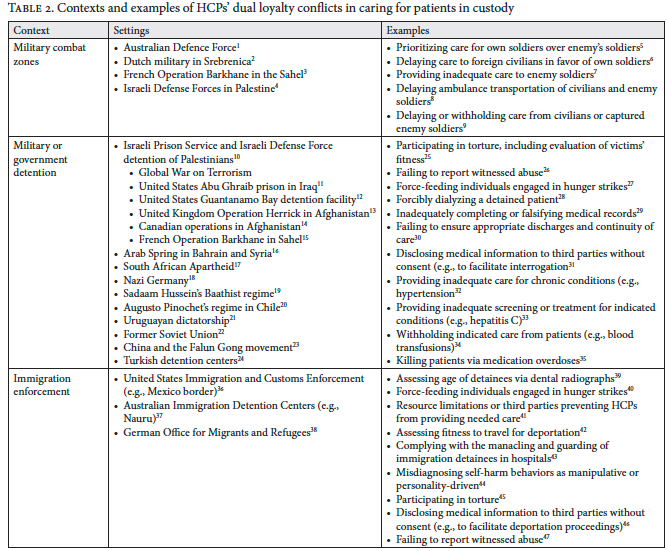

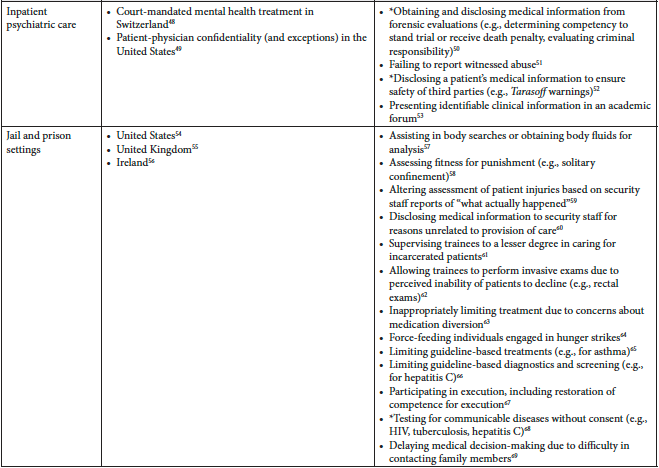

Contexts and examples of dual loyalty conflicts in custodial settings

Across the literature, five common custodial contexts emerged in which HCPs experience dual loyalty conflicts: military combat zones, military and government detention, immigration detention, inpatient psychiatric facilities, and jails and prisons. Within each of these contexts, specific examples illustrate the complexity of the dual loyalty dilemmas, as outlined in Table 2. For example, in military settings, HCPs may prioritize their own soldiers over enemy combatants. In detention settings, HCPs have historically participated in practices such as force-feeding hunger strikers, disclosing confidential medical information to authorities, or even evaluating detainees’ fitness for torture. Immigration enforcement introduces unique dual loyalty dilemmas, such as conducting forensic age assessments or evaluating detainees for deportation despite inadequate medical evaluations. In psychiatric facilities and prisons, conflicts arise in cases involving disclosure of patient information, forensic evaluations, and participation in punitive measures, such as solitary confinement or competency restoration for execution.

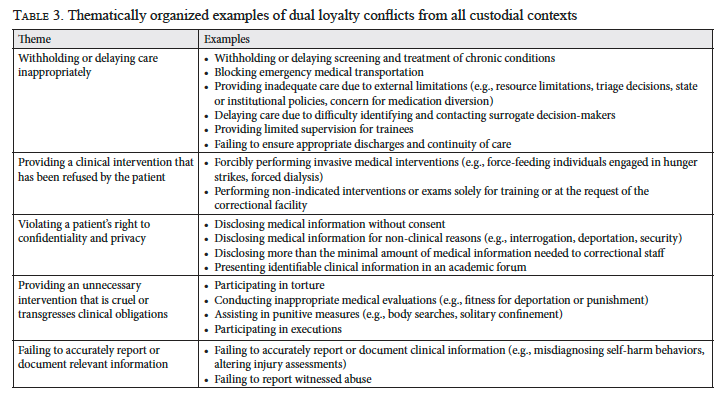

Themes of dual loyalty conflicts in custodial settings

From these diverse contexts in which HCPs work directly in custodial settings, we identified five overarching themes of dual loyalty conflicts, as summarized in Table 3. These themes are as follows:

- Withholding or delaying care inappropriately

DL conflicts may lead HCPs to delay or withhold treatment, particularly in military combat and detention. HCPs may prioritize their own soldiers over enemy combatants or civilians, provide inadequate care, withhold necessary treatments, or delay decisions due to resource constraints. In jails and prisons, concerns about medication misuse may limit appropriate prescribing by HCPs. These dual loyalty dilemmas force HCPs to balance competing priorities between national interests, orders from superiors, loyalty to colleagues or soldiers, security needs, and just allocation of resources.

- Providing interventions against patient wishes

The primary forced intervention highlighted in the literature is force-feeding individuals on hunger strikes. In these situations, HCPs must balance respecting patients’ autonomy and minimizing harm through traumatic force-feeding with institutional priorities of preventing in-custody deaths due to starvation.

- Violating a patient’s right to confidentiality and privacy

HCPs may inappropriately disclose medical information without patient consent or for non-clinical purposes, such as deportation proceedings or interrogations. In these situations, HCPs must balance respecting patients’ rights to privacy and confidentiality, maintaining trust in the patient-physician relationship, upholding societal justice as defined by third parties, promoting institutional security and public safety, and adhering to legal and institutional disclosure policies.

- Engaging in unnecessary or cruel interventions

HCPs have participated in unnecessary and cruel interventions that not only transgress clinical obligations but also contribute to human rights violations. Examples include torture, inappropriate medical evaluations (e.g., age assessments via dental radiographs and fitness for deportation or punishment), punitive measures (e.g., body searches or solitary confinement), and executions. These cases challenge HCPs’ loyalty to colleagues, institutional policies, state-based third parties, legal systems, and national security.

- Falsifying or omitting medical documentation

HCPs may withhold reports of abuse, misdiagnose self-harm behaviors, or alter injury assessments based on non-medical staff reports. In these situations, HCPs face dual loyalty conflicts stemming from their professional obligation to protect patients from harm, legal or institutional reporting requirements, institutional pressure to conceal abuse or avoid negative publicity, and perceived obligations to protect public safety.

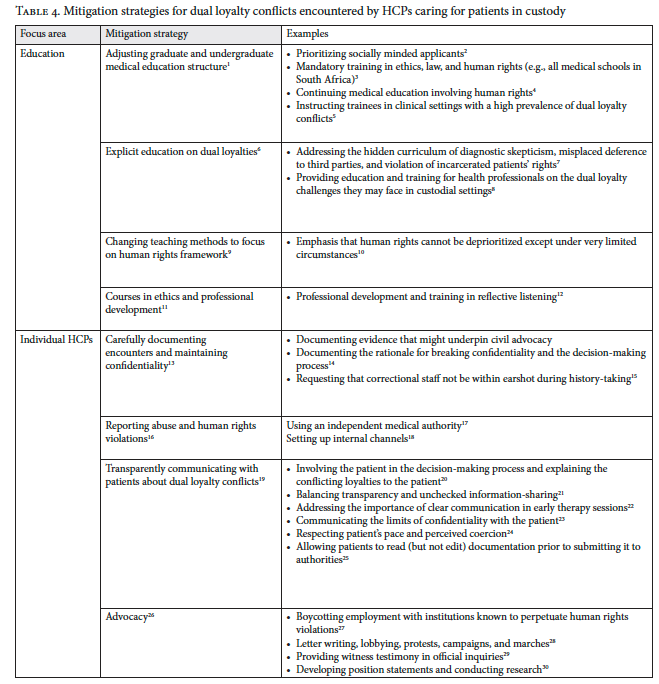

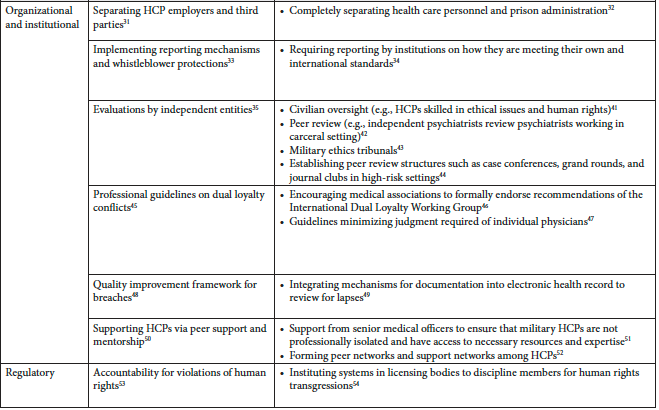

Mitigation strategies for HCPs experiencing dual loyalty conflicts in custodial settings

The reviewed literature also identified a range of strategies to mitigate dual loyalty conflicts, including education, transparent communication between HCPs and patients, and institutional policy development, as detailed in Table 4. Educational interventions include integrating human rights principles into medical school curricula and providing specific training on dual loyalty conflicts. At the individual HCP level, strategies focus on careful documentation, transparent communication with patients about conflicting loyalties, and proactive advocacy efforts. Institutions have sought to mitigate dual loyalty conflicts by ensuring separation between HCPs and third-party influences, establishing whistleblower protections, and adopting mechanisms for independent oversight. Developing quality improvement frameworks and peer support systems can empower individual HCPs to inform organizational policy and seek support when needed.[5]

Discussion

The findings from our literature review demonstrate the diverse contexts and recurring themes of dual loyalty conflicts experienced by HCPs taking care of patients directly in custodial contexts. While these insights offer independently valuable lessons, dual loyalty conflicts also often manifest distinctly in non-custodial, traditional hospitals where community HCPs encounter patients in custody. These HCPs encounter patients in custody less frequently in their day-to-day practice and often without the benefit of formal training or institutional guidance. This lack of clarity may heighten clinicians’ deference to correctional officers or institutional authority, especially when security protocols are unfamiliar or may seem to supersede clinical norms. However, both custodial settings and non-custodial, traditional hospitals are characterized by hierarchical structures, an emphasis on security, and care for patients with limitations on their freedom. In the discussion of our findings, we extend the themes identified in our narrative review of custodial settings to assess how analogous dual loyalty dilemmas arise in non-custodial hospitals. In this process, we hope to provide a framework for understanding the challenges faced by HCPs in non-custodial settings and for identifying tailored mitigation strategies.

Withholding or delaying care inappropriately

As described in Table 3, withholding or delaying care is a common theme of dual loyalty conflicts in custodial settings. In non-custodial hospitals, dual loyalty conflicts in caring for patients in custody can lead HCPs to delay or withhold care due to security concerns resulting from competing loyalties, as outlined in Table 1. For example, institutional pressures from hospital administrators or correctional facilities may result in patients in custody receiving fewer diagnostic tests and treatments than other patients while they are in non-custodial hospitals.[6] These delays mirror examples from custodial settings (Table 2), where prioritization of institutional needs over patient care often hinders timely treatment. Security measures in non-custodial hospitals, such as concealing patients’ locations or treatment plans to mitigate real or perceived safety risks, further extend these delays.[7]

Community HCPs caring for patients in custody also face barriers to effective discharge planning and continuity of care. Security protocols frequently restrict communication by community HCPs with patients in custody about their pending discharge, and follow-up care can be neglected due to difficulties coordinating with correctional facilities.[8] Security protocols may limit communication with patients’ surrogate decision-makers, and adapting follow-up plans to the limited resources available in correctional facilities further complicates safe discharge planning.[9]

Community HCPs often lack guidance on decision-making authority for incapacitated patients in custody, leading to delays in care. Examples from Table 2, such as prioritizing institutional demands over patient autonomy in detention centers, further demonstrate the ingrained systemic barriers that perpetuate these delays. Community HCPs have reported collaborating with correctional staff to make decisions for unrepresented patients, bypassing legal surrogate decision-making processes and violating patients’ decisional rights.[10] This type of violation also occurs within jails and prisons, as noted in Table 2.

Providing interventions against patient wishes

In custodial settings, HCPs may be compelled to perform interventions against patients’ wishes, such as force-feeding or non-indicated procedures (Table 2). Similar conflicts arise in non-custodial hospitals, where community HCPs may incorrectly believe that patients in custody cannot legally refuse recommended treatments.[11] These perceptions by HCPs are often influenced by loyalties to institutional policies or legal frameworks, as can be seen in Table 1. This misconception is evident when correctional staff inappropriately attempt to make unilateral decisions about withdrawing life-sustaining treatment for patients in custody.[12] However, like the general public, patients in custody retain the right to refuse medical interventions, except in cases involving high-risk communicable diseases, forensic testing, or involuntary treatment for severe agitation that poses risks to themselves or others.[13] Overriding an incarcerated patient’s refusal typically requires a court order.

Violating a patient’s right to confidentiality and privacy

As noted in Table 3, breaches of patient confidentiality and privacy are pervasive in all custodial settings, often driven by institutional and legal mandates. These violations are equally problematic in non-custodial hospitals, where community HCPs’ competing loyalties to correctional authorities or fear of legal repercussions (see Table 1) may lead to inadvertent disclosures of medical information to correctional staff.[14] A multi-site study found that less than half of surveyed community HCPs knew how to access policies regarding care for patients in custody, highlighting a significant knowledge gap.[15] In another study, nearly half of surveyed HCPs reported not asking correctional staff to leave the room during patient histories or physical exams, and 42% reported sharing care plans with correctional staff without a clear justification.[16] These patterns can be clearly seen in both custodial and non-custodial settings, representing a central theme of dual loyalty conflicts.

Engaging in unnecessary or cruel interventions

Cruel or unnecessary interventions, such as shackling, are another recurring theme in dual loyalty conflicts identified in Table 3. The routine use of shackling for patients in non-custodial hospitals reflects similar practices by HCPs in multiple custodial settings (see Table 2). Shackling can lead to worse health outcomes by directly interfering with medical interventions, causing psychological distress, and amplifying patients’ feelings of isolation and fear.[17] Shackling has been documented even in situations where security is clearly not a concern.[18] In a single-program survey, over 65% of general surgery residents reported caring for incarcerated patients who were sedated and intubated but remained shackled.[19] However, HCPs often face significant administrative and logistical hurdles in obtaining permission to remove shackles, again demonstrating the strength of various third-party interests in dual loyalty conflicts as listed in Table 1.

Falsifying or omitting medical documentation

Inaccurate or incomplete medical documentation occurs across both custodial and non-custodial settings. Community HCPs often struggle to transfer medical records between custodial and non-custodial hospitals to ensure continuity of care.[20] On a broader scale, the absence of incarcerated patients’ data in national health care databases hinders efforts to monitor and address health disparities in this population, as current and formerly incarcerated individuals are often missing from datasets.[21] These documentation challenges mirror those in custodial settings, where HCPs may be pressured to alter records or misreport clinical findings to avoid exposing human rights violations (see Table 2).

Mitigation strategies

Effective strategies to mitigate dual loyalty conflicts in non-custodial hospitals are those that address the precipitants of the conflicts themselves, namely resource limitations, policy misunderstandings, and challenges in collaborating with correctional institutions.[22] Our literature review highlights three key focus areas for mitigation strategies for dual loyalty conflicts in custodial contexts, as described in Table 4. Within these focus areas, three specific mitigation strategies may be particularly relevant for community HCPs treating patients in custody in non-custodial, traditional hospitals: emphasizing human rights education, transparently discussing existing dual loyalty conflicts with patients in custody, and understanding the policies at one’s own hospitals and correctional facilities.

Medical education in the United States typically emphasizes bioethical analysis to address ethical conflicts. In this framework, ethical principles such as respect for autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice are balanced, often with limited guidance on how or when to prioritize one over another.[23] While these principles can guide patient-centered care, they do not inherently resolve the unique tensions that can arise in dual loyalty conflicts. Thus, this framework may leave HCPs ill-equipped to manage situations where loyalties diverge between patients and other entities. While few United States medical schools have human rights curricula, all South African medical schools require such training.[24] A human rights-based approach to dual loyalty conflicts may better equip community HCPs to manage third-party demands that compromise patient care, as human rights are considered absolute and cannot be negotiated or de-prioritized.[25] One institution in the United States has implemented a human rights curriculum covering human rights frameworks, abuse documentation, and clinical skills for working with affected patients.[26] Human rights training integrated into all levels of medical education and training could better prepare community HCPs to manage dual loyalty dilemmas in non-custodial, traditional hospitals. Partnerships between correctional facilities and academic medical centers (e.g., University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston) highlight opportunities for collaboration.[27]

Community HCPs can mitigate dual loyalty conflicts by clearly communicating the limits of confidentiality and the nature of dual loyalty conflicts with patients in custody. The literature on inpatient psychiatry offers guidance on these disclosures, which are particularly important in non-custodial, traditional hospitals since patients in custody may be unaware of HCPs’ affiliations with correctional institutions. Effective communication involves clearly stating boundaries, explaining reporting obligations, and ensuring that patients understand potential breaches due to legal mandates or institutional pressures.[28] HCPs should specify which types of information will remain confidential and should reassure patients that their health needs are prioritized despite possible coercive pressures from the correctional institution.[29] Given patients’ potential distrust in community HCPs due to uncertainty about their affiliations, building trust at the patient’s preferred pace is essential.[30] This transparent approach has been shown to strengthen patients’ trust in their HCPs.[31]

Finally, community HCPs can more effectively advocate for their patients if they understand policies regarding shackling, privacy, confidentiality, discharge disclosures, refusal of care, follow-up, and communication with patients’ family members at their non-custodial hospitals and at the custodial facilities from which their patients are admitted.[32] These efforts not only improve care within non-custodial hospitals but also set the stage for broader collaboration between HCPs and correctional facilities.

Case study outcome

The hospitalist realizes that she is encountering multiple dual loyalty dilemmas. After discussion with the department chair and hospital legal team, a hospital policy regarding care of incarcerated patients is identified. It clearly states that patients in custody must be within view of correctional officers, but the officers are not required to remain in the room during sensitive history-taking and exams unless a specific security concern is cited. The hospital policy does not comment on shackling, so the hospital administrative team and correctional leadership develop a new agreement that shackles can be moved to a different extremity to allow HCPs to conduct necessary physical exams. The hospital administrative team works with the hospital legal team to develop a policy outlining which information, including protected health information, can be disclosed to specific correctional staff. The hospitalist organizes a series of reflection groups and discussion sessions to raise awareness of dual loyalty dilemmas among HCPs.

Conclusion

The recurring themes of dual loyalty conflicts identified in custodial settings—withholding or delaying care inappropriately, providing interventions against patient wishes, violating a patient’s right to confidentiality and privacy, engaging in unnecessary or cruel interventions, and falsifying or omitting medical documentation—mirror the experiences of community HCPs caring for patients in custody within non-custodial hospitals. These parallels offer a framework for developing mitigation strategies that address the unique challenges faced by community HCPs caring for patients in custody in non-custodial hospital settings.

Future efforts to mitigate dual loyalty conflicts for HCPs in non-custodial settings should focus on developing, implementing, and evaluating these strategies across diverse health care contexts to ensure that community HCPs are equipped to advocate effectively for their patients. Policy makers, correctional facilities, and health care institutions must collaborate to address dual loyalty conflicts experienced by community HCPs caring for patients in custody to improve health care outcomes for this vulnerable population. Addressing dual loyalty conflicts comprehensively will not only safeguard patient rights but also contribute to systemic reforms that reduce health care disparities and promote equity for patients in custody.

Michelle Suh, MD, MHPE, is an assistant professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Brown University, Providence, United States.

Marc David Robinson, MD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, United States.

Holland Kaplan, MD, is an assistant professor in the Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy and the Section of General Internal Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, United States.

Please address correspondence to Holland Kaplan. Email: holland.kaplan@bcm.edu.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2025 Suh, Robinson, and Kaplan. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

[1] International Dual Loyalty Working Group, Dual Loyalty and Human Rights in Health Professional Practice: Proposed Guidelines and Institutional Mechanisms (Physicians for Human Rights and University of Cape Town, Health Sciences Faculty, 2002).

[2] A. Wulz, G. Miller, L. Navon, and J. Daugherty, “Emergency Department Visits by Incarcerated Adults for Nonfatal Injuries — United States, 2010–2019,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 72/11 (2023); L. A. Haber, F. A. Kaiksow, B. A. Williams, and J. T. Crane, “Hospital Care While Incarcerated: A Tale of Two Policies,” Journal of Hospital Medicine 19/3 (2024); L. A. Haber, H. P. Erickson, S. R. Ranji et al., “Acute Care for Patients Who Are Incarcerated: A Review,” JAMA Internal Medicine 179/11 (2019); J. E. Glenn, A. M. Bennett, R. J. Hester, et al., “‘It’s like Heaven over There’: Medicine as Discipline and the Production of the Carceral Body,” Health and Justice 8/1 (2020); R. E. Armstrong, K. A. Hendershot, N. P. Newton, and P. D. Panakos, “Addressing Emergency Department Care for Patients Experiencing Incarceration: A Narrative Review,” Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 24/4 (2023); M. Suh, M. F. Molina, A. N. Chary, et al., “A Multi-Site Assessment of Emergency Staff Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Care for Incarcerated Patients,” American Journal of Emergency Medicine 82 (2024); S. K. Chao, R. Clark, M. Susalla, and D. L. Lewis, “Resident Experiences at a Community Hospital Caring for Patients Who Are Incarcerated,” Journal of Correctional Health Care 31/1 (2025)

[3] R. Conger, R. Treat, and S. Hofmeister, “The Importance of Correctional Health Care Curricula in Medical Education,” Journal of Correctional Health Care 28/2 (2022); M. English, F. Sanogo, R. Trotzky-Sirr, et al., “Medical Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes Regarding Justice-Involved Health,” Healthcare 9/10 (2021); M. Suh, S. Chao, M. G. Gazzolla, and W. Weber, “Resident Education and the Care of Patients With Criminal-Legal System Involvement in the Emergency Department,” Annals of Emergency Medicine 86/1 (2025).

[4] American Public Health Association, “A Call to Stop Shackling Incarcerated Patients Seeking Health Care” (2023), https://www.apha.org/policy-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-briefs/policy-database/2024/01/16/shackling-incarcerated-patients; S. Chao, W. Weber, K. V. Iserson, et al., “Best Practice Guidelines for Evaluating Patients in Custody in the Emergency Department,” Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open 5/2 (2024).

[5] N. Duvall, “‘From Defensive Paranoia to …Openness to Outside Scrutiny’: Prison Medical Officers in England and Wales, 1979–86,” Medical History 62/1 (2018); S. Sirkin, K. Hampton, and R. Mishori, “Health Professionals, Human Rights Violations at the US-Mexico Border, and Holocaust Legacy,” AMA Journal of Ethics 23/1 (2021); A. Lamblin, C. Derkenne, M. Trousselard, and M.-A. Einaudi, “Ethical Challenges Faced by French Military Doctors Deployed in the Sahel (Operation Barkhane): A Qualitative Study,” BMC Medical Ethics 22/1 (2021); M. C. Reade, “Whose Side Are You on? Complexities Arising from the Non-Combatant Status of Military Medical Personnel,” Monash Bioethics Review 41/1 (2023); D. S. Shaivitz, “Medicate-to-Execute: Current Trends in Death Penalty Jurisprudence and the Perils of Dual Loyalty,” Journal of Health Care Law and Policy 7/1 (2004).

[6] K. C. Brooks, A. N. Makam, and L. A. Haber, “Caring for Hospitalized Incarcerated Patients: Physician and Nurse Experience,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 37/2 (2022); A. D. Douglas, M. Y. Zaidi, T. K. Maatman, et al., “Caring for Incarcerated Patients: Can It Ever Be Equal?,” Journal of Surgical Education 78/6 (2021).

[7] Chao (see note 2); W. C. Burkett, Y. Iwai, P. A. Gehrig, and A. K. Knittel, “Fractured and Delayed: A Qualitative Analysis of Disruptions in Care for Gynecologic Malignancies during Incarceration,” Gynecologic Oncology 176 (2023).

[8] Brooks et al. (see note 6); Douglas et al. (see note 6); Suh (see note 2).

[9] Chao (see note 2); Haber (see note 2); Burkett et al. (see note 7); S. Panozzo, T. Bryan, A. Collins, et al., “Complexities and Constraints in End-of-Life Care for Hospitalized Prisoner Patients,” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 60/5 (2020).

[10] S. Batbold, J. D. Duke, K. A. Riggan, and E. S. DeMartino, “Decision-Making for Hospitalized Incarcerated Patients Lacking Decisional Capacity,” JAMA Internal Medicine 184/1 (2024).

[11] Brooks et al. (see note 6).

[12] Batbold et al. (see note 10); L. Fuller and M. M. Eves, “Incarcerated Patients and Equitability: The Ethical Obligation to Treat Them Differently,” Journal of Clinical Ethics 28/4 (2017).

[13] Chao (see note 2).

[14] Haber et al. (see note 2); Batbold et al. (see note 10); Fuller and Eves (see note 12).

[15] Brooks et al. (see note 6); Douglas et al. (see note 6).

[16] S. Fazel and J. Baillargeon, “The Health of Prisoners,” Lancet 377/9769 (2011).

[17] M. Borgo and M. Picozzi, “The Separation Wall and the Right to Healthcare,” Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 19/4 (2016); Burkett et al. (see note 7); M. Robinson, K. Lavere, and E. Porsa, “End the Routine Shackling of Incarcerated Inpatients,” Journal of Hospital Medicine 16/6 (2021); L. A. Haber, L. A. Pratt, H. P. Erickson, and B. A. Williams, “Shackling in the Hospital,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 37/5 (2022); N. S. Bedi, N. Mathur, J. D. Wang, et al., “Human Rights in Hospitals: An End to Routine Shackling,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 39/6 (2024).

[18] N. Bar, E. Naaman, D. Rosin, et al., “Shackling Incarcerated People in Israeli Hospitals—a Multicentre Study Followed by a National Intervention Programme,” Lancet 402/10398 (2023); A. D. Bansal and L. A. Haber, “On a Ventilator in Shackles,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 36/12 (2021).

[19] Douglas et al. (see note 6).

[20] Burkett et al. (see note 7); Suh et al. (see note 2); N. P. Morris and Y. Zisman-Ilani, “Communication Over Incarceration: Improving Care Coordination Between Correctional and Community Mental Health Services,” Psychiatric Services 73/12 (2022).

[21] C. Ahalt, I. A. Binswanger, M. Steinman, et al., “Confined to Ignorance: The Absence of Prisoner Information from Nationally Representative Health Data Sets,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 27/2 (2012).

[22] Chao (see note 2); Batbold et al. (see note 10); M. K. Bryant et al., “Outcomes after Emergency General Surgery and Trauma Care in Incarcerated Individuals: An EAST Multicenter Study,” Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 93/1 (2022).

[23] International Dual Loyalty Working Group (see note 1).

[24] K. C. McKenzie, R. Mishori, and H. Ferdowsian, “Twelve Tips for Incorporating the Study of Human Rights into Medical Education,” Medical Teacher 42/8 (2020); K. Moodley and S. Kling, “Dual Loyalties, Human Rights Violations, and Physician Complicity in Apartheid South Africa,” AMA Journal of Ethics 17/10 (2015).

[25] L. London, L. S. Rubenstein, L. Baldwin-Ragaven, and A. Van Es, “Dual Loyalty among Military Health Professionals: Human Rights and Ethics in Times of Armed Conflict,” Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 15/04 (2006).

[26] McKenzie et al. (see note 24).

[27] A. H. Hashmi, A. M. Bennett, N. N. Tajuddin, et al., “Qualitative Exploration of the Medical Learner’s Journey into Correctional Health Care at an Academic Medical Center and Its Implications for Medical Education,” Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice 26/2 (2021).

[28] D. Lowenthal, “Case Studies in Confidentiality,” Journal of Psychiatric Practice 8/3 (2002).

[29] M. L. Perlin, “Power Imbalances in Therapeutic and Forensic Relationships,” Behavioral Sciences and the Law 9/2 (1991).

[30] H. Merkt, T. Wangmo, F. Pageau, et al., “Court-Mandated Patients’ Perspectives on the Psychotherapist’s Dual Loyalty Conflict: Between Ally and Enemy,” Frontiers in Psychology 11 (2021).

[31] Ibid.

[32] Suh et al. (see note 2); Haber et al. (see note 2); M. Eichelberger, M. M. Wertli, and N. T. Tran, “Equivalence of Care, Confidentiality, and Professional Independence Must Underpin the Hospital Care of Individuals Experiencing Incarceration,” BMC Medical Ethics 24/1 (2023).

Table 2 References

[1] M. Vinson, “Dual Loyalty and the Medical Profession for Australian Defence Force Medical Officers,” Journal of Military and Veterans Health 30/4 (2022).

[2] F. B. Hooft, “Legal Framework Versus Moral Framework: Military Physicians and Nurses Coping with Practical and Ethical Dilemmas,” Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps 165/4 (2019).

[3] A. Lamblin, C. Derkenne, M. Trousselard, and M.-A. Einaudi, “Ethical Challenges Faced by French Military Doctors Deployed in the Sahel (Operation Barkhane): A Qualitative Study,” BMC Medical Ethics 22/1 (2021).

[4] M. Borgo and M. Picozzi, “The Separation Wall and the Right to Healthcare,” Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 19/4 (2016); K. Moodley and S. Kling, “Dual Loyalties, Human Rights Violations, and Physician Complicity in Apartheid South Africa,” AMA Journal of Ethics 17/10 (2015).

[5] Vinson (see note 1); Lamblin et al. (see note 3).

[6] Hooft (see note 6).

[7] Lamblin et al. (see note 3).

[8] Borgo and Picozzi (see note 4).

[9] Lamblin et al. (see note 3); M. L. Gross, “Military Medical Ethics: A Review of the Literature and a Call to Arms,” Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 22/1 (2013).

[10] N. Michaeli, A. Litvin, and N. Davidovitch, “Hepatitis C in Israeli Prisons: Status Report,” Harm Reduction Journal 17/1 (2020); D. Filc, H. Ziv, M. Nassar, and N. Davidovitch, “Palestinian Prisoners’ Hunger-Strikes in Israeli Prisons: Beyond the Dual-Loyalty in Medical Practice and Patient Care,” Public Health Ethics 7/3 (2014).

[11] P. A. Clark, “Medical Ethics at Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib: The Problem of Dual Loyalty,” Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics: A Journal of the American Society of Law, Medicine and Ethics 34/3 (2006).

[12] Ibid.; F. Rosner, “Ethical Dilemmas for Physicians in Time of War,” Israel Medical Association Journal 12 (2010); S. M. Dougherty, J. Leaning, P. G. Greenough, and F. M. Burkle, “Hunger Strikers: Ethical and Legal Dimensions of Medical Complicity in Torture at Guantanamo Bay,” Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 28/6 (2013); J. A Singh, “Military Tribunals at Guantanamo Bay: Dual Loyalty Conflicts,” Lancet 362/9383 (2003).

[13] R. G. Simpson, D. Wilson, and J. J. Tuck, “Medical Management of Captured Persons,” Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps 16/01 (2014).

[14] P. Webster, “Canadian Soldiers and Doctors Face Torture Allegations,” Lancet 369/9571 (2007).

[15] Lamblin et al. (see note 3).

[16] L. Hathout, “The Right to Practice Medicine without Repercussions: Ethical Issues in Times of Political Strife,” Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine 7/1 (2012).

[17] Moodley and Kling (see note 4); Rosner (see note 12); L. London, L. S. Rubenstein, L. Baldwin-Ragaven, and A. Van Es, “Dual Loyalty among Military Health Professionals: Human Rights and Ethics in Times of Armed Conflict,” Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 15/04 (2006).

[18] S. Sirkin, K. Hampton, and R. Mishori, “Health Professionals, Human Rights Violations at the US-Mexico Border, and Holocaust Legacy,” AMA Journal of Ethics 23/1 (2021).

[19] Rosner (see note 12); Singh (see note 12); Simpson et al. (see note 13).

[20] International Dual Loyalty Working Group, Dual Loyalty and Human Rights in Health Professional Practice: Proposed Guidelines and Institutional Mechanisms (Physicians for Human Rights and University of Cape Town, Health Sciences Faculty, 2002).

[21] G. Bloche, “Uruguay’s Military Physicians,” JAMA 255/20 (1986).

[22] H. Reyes, “Confidentiality Subject to National Law: Should Doctors Always Comply?,” Journal of the Royal Danish Medical Association 51/9 (1996).

[23] R. Munro, “Judicial Psychiatry in China and Its Political Abuses,” Columbia Journal of Asian Law 13/2 (2000).

[24] Physicians for Human Rights, Torture in Turkey and Its Unwilling Accomplices (Physicians for Human Rights, 1996).

[25] Clark (see note 11); Rosner (see note 12); Singh (see note 12); London et al. (see note 17); International Dual Loyalty Working Group (see note 1); Bloche (see note 21); J. Sonntag, “Doctors’ Involvement in Torture,” Torture 18/3 (2008).

[26] M. Z. Solomon, “Healthcare Professionals and Dual Loyalty: Technical Proficiency Is Not Enough,” Medscape General Medicine 7/3 (2005).

[27] Filc et al. (see note 14); Dougherty et al. (see note 16); Singh (see note 16).

[28] D. Zupan, G. Solis, R. Schoonhoven, and G. Annas, “Case Study: Dialysis for a Prisoner of War,” Hastings Center Report 34/6 (2004).

[29] Moodley and Kling (see note 4); Rosner (see note 12); London et al. (see note 17); Bloche (see note 21); Reyes (see note 22); Solomon (see note 26).

[30] Singh (see note 12); Simpson et al. (see note 13); Sirkin et al. (see note 18).

[31] Rosner (see note 12); Physicians for Human Rights (see note 24); Solomon (see note 26); Jesper (see note 2); M. G. Bloche and J. H. Marks, “Doctors and Interrogators at Guantanamo Bay,” New England Journal of Medicine 353/1 (2005).

[32] Lamblin et al. (see note 3); Simpson et al. (see note 13).

[33] Michaeli et al. (see note 10).

[34] Hathout (see note 16); Bloche (see note 21).

[35] International Dual Loyalty Working Group (see note 20); Munro (see note 23).

[34] Sirkin et al. (see note 18); J. M. Appel, “Divided Loyalties: Fire and ICE,” Hastings Center Report 51/6 (2021); P. Spiegel, N. Kass, and L. Rubenstein, “Can Physicians Work in US Immigration Detention Facilities While Upholding Their Hippocratic Oath?,” JAMA 322/15 (2019).

[35] M. Dudley, P. Young, L. Newman, and F. Gale, “Health Professionals Confront the Intentional Harms of Indefinite Immigration Detention: An Australian Overview, Evaluation of Alternative Responses and Proposed Strategy,” International Journal of Migration Health and Social Care 17/1 (2021); R. Essex, “Healthcare and Clinical Ethics in Australian Offshore Immigration Detention,” International Journal of Human Rights 20/7 (2016); R. Essex, “Human Rights, Dual Loyalties, and Clinical Independence: Challenges Facing Mental Health Professionals Working in Australia’s Immigration Detention Network,” Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 11/1 (2014); J. Sanggaran and D. Zion, “Is Australia Engaged in Torturing Asylum Seekers? A Cautionary Tale for Europe,” Journal of Medical Ethics 42/7 (2016); D. Zion, L. Briskman, and B. Loff, “Psychiatric Ethics and a Politics of Compassion: The Case of Detained Asylum Seekers in Australia,” Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 9/1 (2012); R. Stoddart, P. Simpson, and B. Haire, “Medical Advocacy in the Face of Australian Immigration Practices: A Study of Medical Professionals Defending the Health Rights of Detained Refugees and Asylum Seekers,” PLOS One 15/8 (2020); J. Sanggaran, B. Haire, and D. Zion, “The Health Care Consequences Of Australian Immigration Policies,” PLOS Medicine 13/2 (2016); R. Essex, “Healthcare and Complicity in Australian Immigration Detention,” Monash Bioethics Review 34/2 (2016).

[36] C. Pross, “The Police Medical Service of Berlin: Doctors or Agents of the State?,” Lancet 356/9239 (2000).

[37] Sirkin et al. (see note 18).

[38] Ibid.; Sanggaran and Zion (see note 35).

[39] Sirkin et al. (see note 18); Spiegel et al. (see note 34); Essex, “Healthcare and Clinical Ethics” (see note 35); Essex, “Human Rights” (see note 35); Zion et al. (see note 35); Stoddart et al. (see note 35); Sanggaran et al. (see note 35).

[40] Dudley et al. (see note 35); Essex, “Human Rights” (see note 35).

[41] Dudley et al. (see note 35).

[42] Ibid.

[43] Sanggaran and Zion (see note 35).

[44] Sirkin et al. (see note 18); Appel (note 34); Essex, “Healthcare and Complicity” (see note 35); Pross (see note 36).

[45] Sanggaran and Zion (see note 35); Sanggaran et al. (see note 35).

[46] H. Merkt, T. Wangmo, F. Pageau, et al., “Court-Mandated Patients’ Perspectives on the Psychotherapist’s Dual Loyalty Conflict: Between Ally and Enemy,” Frontiers in Psychology 11 (2021); H. Merkt, S. Haesen, A. Eytan, and E. Habermayer, “Forensic Mental Health Professionals’ Perceptions of Their Dual Loyalty Conflict: Findings from a Qualitative Study,” BMC Medical Ethics 22/1 (2021).

[47] D. Lowenthal, “Case Studies in Confidentiality,” Journal of Psychiatric Practice 8/3 (2002); M. L. Perlin, “Power Imbalances in Therapeutic and Forensic Relationships,” Behavioral Sciences and the Law 9/2 (1991).

[48] Lowenthal (see note 47); Perlin (see note 47).

[49] Lowenthal (see note 47).

[50] Ibid.; Merkt et al., “Court-Mandated” (see note 46).

[51] Lowenthal (see note 47).

[52] R. Kalra, S. G. Kollisch, R. MacDonald, et al., “Staff Satisfaction, Ethical Concerns, and Burnout in the New York City Jail Health System,” Journal of Correctional Health Care 22/4 (2016); B. S. Elger, “Medical Ethics in Correctional Healthcare: An International Comparison of Guidelines,” Journal of Clinical Ethics 19/3 (2008); J. E. Elumn, L. Keating, A. B. Smoyer, and E. A. Wang, “Healthcare-Induced Trauma in Correctional Facilities: A Qualitative Exploration,” Health and Justice 9/1 (2021); A. H. Hashmi, A. M. Bennett, N. N. Tajuddin, et al., “Qualitative Exploration of the Medical Learner’s Journey into Correctional Health Care at an Academic Medical Center and Its Implications for Medical Education,” Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice 26/2 (2021); M. Barragan, G. Gonzalez, J. D. Strong, et al., “Triaged Out of Care: How Carceral Logics Complicate a ‘Course of Care’ in Solitary Confinement,” Healthcare 10/2 (2022); J. Pont, H. Stöver, and H. Wolff, “Dual Loyalty in Prison Health Care,” American Journal of Public Health 102/3 (2012); R. MacDonald, A. Parsons, and H. D. Venters, “The Triple Aims of Correctional Health: Patient Safety, Population Health, and Human Rights,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 24/3 (2013); S. Glowa-Kollisch, J. Graves, N. Dickey, et al., “Data-Driven Human Rights: Using Dual Loyalty Trainings to Promote the Care of Vulnerable Patients in Jail,” Health and Human Rights 17/1 (2015).

[53] N. Duvall, “‘From Defensive Paranoia to …Openness to Outside Scrutiny’: Prison Medical Officers in England and Wales, 1979–86,” Medical History 62/1 (2018); Perlin (see note 47); D. S. Shaivitz, “Medicate-to-Execute: Current Trends in Death Penalty Jurisprudence and the Perils of Dual Loyalty,” Journal of Health Care Law and Policy 7/1 (2004); Hashmi et al. (see note 52); Barragan (see note 52); Pont et al. (see note 52); MacDonald et al. (see note 52); Kalra et al. (see note 52); G. Gulati, B. D. Kelly, D. Meagher, et al., “Hunger Strikes in Prisons: A Narrative Systematic Review of Ethical Considerations from a Physician’s Perspective,” Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine 35/2 (2018); Glowa-Kollisch et al. (see note 52); Elger (see note 52); Elumn et al. (see note 52)

[54] D. Crowley, M. C. Van Hout, C. Murphy, et al., “Hepatitis C Virus Screening and Treatment in Irish Prisons from a Governor and Prison Officer Perspective: A Qualitative Exploration,” Health and Justice 6/1 (2018).

[55] Pont et al. (see note 52).

[56] Ibid.; Barragan et al. (see note 52); Glowa-Kollisch et al. (see note 52).

[57] Glowa-Kollisch et al. (see note 52).

[58] Ibid.; Hashmi et al. (see note 52); Pont et al. (see note 52); Kalra et al. (see note 52); Elger (see note 52).

[59] Hashmi et al. (see note 52).

[60] Ibid.

[61] Glowa-Kollisch et al. (see note 52).

[62] Gulati et al. (see note 53).

[63] Elger (see note 52).

[64] Crowley et al. (see note 54).

[65] Sirkin et al. (see note 18); Appel (note 36); Essex, “Human Rights” (see note 35); Pross (see note 36); Sanggaran and Zion (see note 35); Sanggaran et al. (see note 35); Merkt et al., “Court-Mandated Patients’ Perspectives” (see note 46); Merkt et al., “Forensic Mental Health Professionals’ Perceptions (see note 46); Duvall (see note 53); Perlin (see note 47); Shaivitz (see note 53); Hashmi et al. (see note 52); Barragan (see note 52); Pont et al. (see note 52); MacDonald et al. (see note 52); Kalra et al. (see note 52); Gulati et al. (see note 53); Glowa-Kollisch et al. (see note 52); Elger (see note 52); Elumn et al. (see note 52).

[66] MacDonald et al. (see note 52).

[67] Hashmi et al. (see note 52).

Table 4 References

[1] K. Moodley and S. Kling, “Dual Loyalties, Human Rights Violations, and Physician Complicity in Apartheid South Africa,” AMA Journal of Ethics 17/10 (2015); International Dual Loyalty Working Group, Dual Loyalty and Human Rights in Health Professional Practice: Proposed Guidelines and Institutional Mechanisms (Physicians for Human Rights and University of Cape Town, Health Sciences Faculty, 2002); R. Stoddart, P. Simpson, and B. Haire, “Medical Advocacy in the Face of Australian Immigration Practices: A Study of Medical Professionals Defending the Health Rights of Detained Refugees and Asylum Seekers,” PLOS One 15/8 (2020).

[2] Stoddart et al. (see note 1).

[3] Moodley and Kling (see note 1).

[4] Ibid.; International Dual Loyalty Working Group, (see note 1); Stoddart et al. (see note 1).

[5] Moodley and Kling (see note 1); International Dual Loyalty Working Group (see note 1); Stoddart et al. (see note 1).

[6] International Dual Loyalty Working Group (see note 1); M. Z. Solomon, “Healthcare Professionals and Dual Loyalty: Technical Proficiency Is Not Enough,” Medscape General Medicine 7/3 (2005); D. S. Shaivitz, “Medicate-to-Execute: Current Trends in Death Penalty Jurisprudence and the Perils of Dual Loyalty,” Journal of Health Care Law and Policy 7/1 (2004); J. A. Singh, “American Physicians and Dual Loyalty Obligations in the ‘War on Terror’,” BMC Medical Ethics 4 (2003); M. I. Suh and M. D. Robinson, “Vulnerable yet Unprotected: The Hidden Curriculum of the Care of the Incarcerated Patient,” Journal of Graduate Medical Education 14/6 (2022).

[7] Suh and Robinson (see note 6).

[8] Shaivitz (see note 6); Singh (see note 6).

[9] L. London, L. S. Rubenstein, L. Baldwin-Ragaven, and A. Van Es, “Dual Loyalty among Military Health Professionals: Human Rights and Ethics in Times of Armed Conflict,” Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 15/04 (2006); H. G. Atkinson, “Preparing Physicians to Contend with the Problem of Dual Loyalty,” Journal of Human Rights 18/3 (2019).

[10] London et al. (see note 9); International Dual Loyalty Working Group (see note 1); Atkinson (see note 9).

[11] B. S. Elger, “Medical Ethics in Correctional Healthcare: An International Comparison of Guidelines,” Journal of Clinical Ethics 19/3 (2008); E. Elumn, L. Keating, A. B. Smoyer, and E. A. Wang, “Healthcare-Induced Trauma in Correctional Facilities: A Qualitative Exploration,” Health and Justice 9/1 (2021).

[12] Elumn et al. (see note 11).

[13] International Dual Loyalty Working Group (see note 1); Stoddart et al. (see note 1); D. Lowenthal, “Case Studies in Confidentiality,” Journal of Psychiatric Practice 8/3 (2002); J. P. Winters, F. Owens, and E. Winters, “Dirty Work: Well-Intentioned Mental Health Workers Cannot Ameliorate Harms in Offshore Detention,” Journal of Medical Ethics 49/8 (2023).

[14] Lowenthal (see note 13).

[15] International Dual Loyalty Working Group (see note 1).