A Content Review of National Dementia Plans: Are Human Rights Considered?

Vol 27/1, 2025, pp. 43-57 PDF

Briony Harden, Yinuo Mao, Justin Weiss, Selina Hsuan, Orii McDermott, Michelle Funk, Natalie Drew, Katrin Seeher, Tarun Dua, and Martin Orrell

Abstract

The World Health Organization has set a target for 75% of member states to have national dementia plans by 2025. These plans should align with human rights standards, such as the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. The aim of this study was to complete a review of global national dementia plans and their human rights content according to the convention’s principles. A categorization matrix of pre-identified human rights themes was produced prior to data collection and extensive inclusion criteria were adopted to ensure thorough assessment using deductive content analysis. Each dementia plan was reviewed by at least two independent assessors. Forty plans were included in the final analysis. We found that basic human rights were covered by the plans, with community inclusion acknowledged in 39 plans (97.5%). However, there was less coverage of non-coercive practices and the participation of people with dementia in the design and delivery of services or policies, with only 24 plans (60%) mentioning these aspects. This is the first global review of human rights content within national dementia plans. More must be done to ensure that all such plans align with human rights standards so that the human rights of persons with dementia are respected, protected, and promoted.

Introduction

People with dementia often experience infringements of their human rights. For example, in many countries, such individuals have commonly been denied legal capacity due to the use of substitute decision-making processes and coercive practices in care services.[1] Coercive practices such as involuntary treatment, seclusion, and restraints can exclude people with dementia from the wider community and significantly worsen their well-being and quality of life.[2] Also, sometimes persons with dementia are provided with only limited and segregated activities, are denied choice, and have little to no access to community spaces.[3] Moreover, they have rarely been included in opportunities to participate in the design or delivery of services or policies that affect them.[4]

In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) adopted its Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia 2017–2025, which aims to achieve “a world in which … people with dementia and their carers live well and receive the care and support they need to fulfil their potential with dignity, respect, autonomy and equality.”[5] All 194 WHO member states adopted this plan at the World Health Assembly in 2017, signifying a commitment to make dementia a priority. The first action area of the plan calls for 75% of WHO member states to develop and implement national dementia policies, strategies, or plans by 2025.[6]

WHO’s Global Action Plan states that dementia plans should be underpinned by human rights principles aligning with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and other rights standards.[7] The CRPD has been ratified by 186 countries, meaning that these governments have agreed to incorporate its principles into their policies and practices.[8] This is highly significant because there is growing concern over the human rights violations of people with dementia and there have been arguments that governments are not doing enough to protect those with dementia and their care partners.[9]

The priorities of dementia plans have ranged from specific care and treatment frameworks to the inclusion of and equality for people with dementia.[10] Previous reviews of dementia plans that have focused on human rights have not examined a broad range of plans; however, Alzheimer Europe identified in a 2023 report that the number of plans reporting legal mechanisms to protect legal capacity, such as advance care planning, has increased.[11] It also reported that the number of plans aligning with human rights standards has risen.[12] Hence, there is now a need for a global review of the human rights content of national dementia plans.

Methods

Design

We used deductive content analysis to conduct a comprehensive assessment of human rights content in global dementia plans.[13] We chose this design due to its effectiveness in categorizing large amounts of qualitative data, allowing for a broad yet precise summarization of a particular phenomenon in both data collection and analysis.[14] Additionally, it is a flexible approach to collection and analysis that allows a significant number of key words relating to human rights in the national dementia plans to be identified.

Procedure

Search strategy. We identified dementia plans through the Alzheimer Disease International (ADI) and Alzheimer Europe websites and WHO’s MiNDbank database. MiNDbank is an online database that provides easy access to international resources, including national policies.[15] We also conducted scoping searches on Google and Google Scholar using the search strategy “‘country’ + ‘dementia plan OR dementia strategy,’” with results limited to the first 10 pages. We conducted these searches between March and May 2023 and downloaded all plans into PDFs.

Inclusion criteria. To be included within our review, plans had to be:

- national dementia plans or strategies

- developed after the adoption of the CRPD[16]

- developed by the national government or ministry of health

- for a country that is a United Nations member state[17]

- publicly accessible

- written in English or amenable to translation

- the most recent version of the government plan (regardless of whether the implementation period was over).

Translation. We downloaded several plans not available in English. ADI recommended DocTranslator, a translation website, to help translate the plans into English.[18] For most plans, this website worked well. For plans that could not be translated due to their underlying format, we copied paragraphs into Google Translate.

Materials. BH created a categorization matrix in the form of a template to enable a systematic content search relating to human rights. The template contained specific CRPD articles to ensure that the five human rights aspects we were particularly interested in were incorporated (see predetermined human rights themes). These included articles 5, 8, 9, 12, 14, 15, 16, 19, 25, 27, 28, and 29. We took inspiration from ADI and Dementia Alliance International’s 2016 report.[19] We also included other words and terms synonymous with human rights, such as “autonomy,” “empowerment,” and “legal capacity,” which allowed us to obtain a more complete picture of the human rights content. We also searched for specific mentions of the CRPD, the WHO global action plan, and the terms “human right(s)” or “right(s).” The template included space for the name and year of the plan, the name of the assessor, and a summary of the plan to be written. Additionally, BH created a glossary of the CRPD articles and rights synonyms. The template and glossary were created in Microsoft Word before the template was transferred to JISC Online Surveys V2 and shared with the team.

Piloting. To ensure the validity and reliability of the template, the assessors (BH, YM, JW, and SH) piloted three plans from different WHO regions. The four assessors individually searched for the human rights content using the search function (Ctrl+F) on the plans and inputted key words from the template. All assessors then read through the entire plans to contextualize the content found and ensure that no information was missed. The human rights content identified through our searches was extracted word for word, complete with the page number(s), and was submitted to the online survey template for BH to download and add to a shared OneDrive folder. BH then collated the submitted data and produced a feedback sheet before discussing this with principal investigator, MO. A team meeting was held with the other three assessors to talk through any discrepancies. By piloting, we guaranteed the reliability of our methods regarding consistency in our analysis of plans. We also ensured high validity in our methods, using the CRPD principles and related synonyms to analyze the plans.

Final procedure. Once piloting was complete, the remaining plans were randomly and equally distributed among YM, JW, and SH before being randomly assigned to a second reviewer; this ensured that plans were independently assessed at least twice. After examination, the assessors met with one another to complete consensus work and discuss any discrepancies. BH read through every national dementia plan included for analysis. If no agreement could be made, BH and MO met to analyze and agree on the remaining issues. Afterward, the data were transferred to Excel spreadsheets, allowing the team to clearly identify any gaps in the content. BH and YM then combined the data and removed any duplications.

Analysis

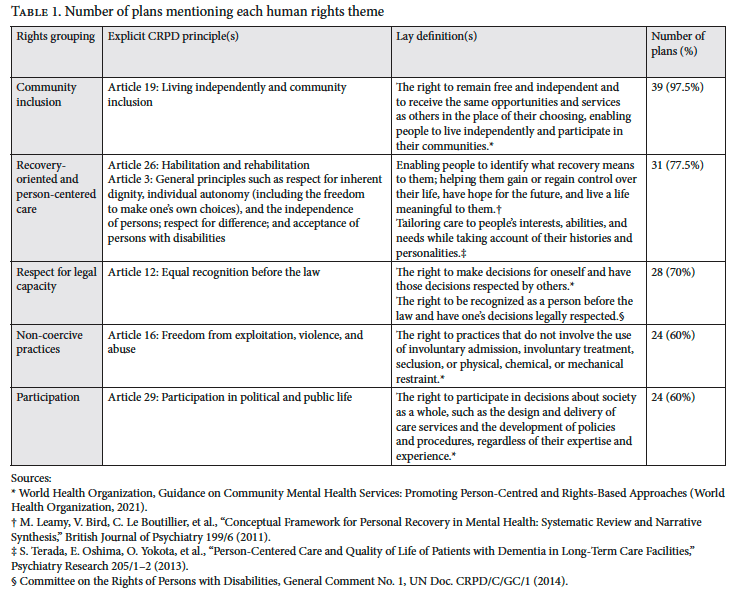

Predetermined human rights themes. We assembled the themes to match the rights groups from WHO’s QualityRights initiative, a global initiative guided by CRPD principles that aims to improve the lives of people with mental health conditions and psychosocial disabilities, including dementia.[20] In its guidance for community mental health services, WHO states that the right to health for people with mental health conditions and psychosocial disabilities depends on a number of fundamental human rights principles: respect for legal capacity; non-coercive practices; participation; community inclusion; and recovery-oriented and person-centered care.[21] See Table 1 for definitions.

Results

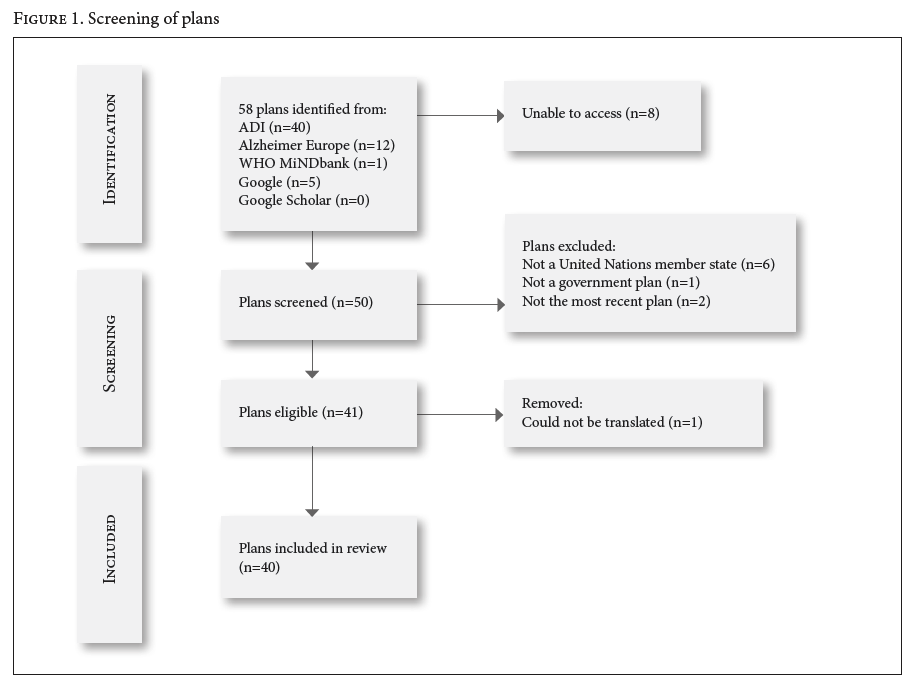

Our searches identified 58 plans worldwide. After screening (see Figure 1), we included 40 plans in our final analysis (this list is available upon request).

The eight plans we could not gain access to were those for Armenia, China, the Republic of Korea (version four), Russia, Singapore, Thailand, Uruguay (2023 version), and Vietnam. We could not translate the plan from Costa Rica due to the underlying format (the translation website would not recognize the PDF, nor could we copy and paste individual paragraphs into Google Translate). We excluded the plans of Bonaire, Curaçao, Gibraltar, Macao SAR, Puerto Rico, and Taiwan because they do not pertain to United Nations member states.[22] Although we were able to access the plans of Uruguay (from 2016) and the Republic of Korea (version three), we excluded them from our analysis because they are not the most recent plans.[23]

Summary of plans analyzed

The plans analyzed were launched between 2010 and 2023, with Belgium (Wallonia) the oldest plan and Scotland’s fourth version the most recent.[24] Plans where the implementation period had expired but no further plan had been launched (for example, Australia) were also included.[25] Twenty-seven plans were from the European WHO region (Austria, Belgium Flanders, Belgium Wallonia, Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, England, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Northern Ireland, Norway, Portugal, Scotland, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and Wales), six from the Americas (Canada, Chile, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and the United States), three from the Eastern Mediterranean (Iran, Kuwait, and Qatar), three from Western Pacific (Australia, Japan, and New Zealand), and one from Southeast Asia (Indonesia). There were no plans from Africa. Despite the Belgium Flanders and Belgium Wallonia plans coming from one United Nations member state, we chose to include both of them due to their different governments.[26] Similarly, we included the plans from all four countries in the United Kingdom. Thirty-five plans were from high-income countries, four from upper-middle-income countries, and one from a lower-middle-income country.

Thirty-eight plans were dementia specific, and two plans (Finland and Qatar) integrated dementia into other plans such as Qatar’s National Health Strategy 2018–2022.[27] All plans provided a global and national context for their rationale, and all dementia-specific plans provided a summary of dementia as a condition, its etiology, and risk factors. Some plans also contextualized each of their action areas.

Human rights

Of the plans analyzed, 11 (27.5%) mentioned the CRPD, whether in the main body of the plan or the references. In addition, 10 out of the 21 plans launched after 2017 mentioned WHO’s global action plan. Table 1 shows the number of plans that mentioned anything in relation to the human rights themes, with examples of the explicit CRPD articles that relate to each theme.[28]

CRPD articles work together to ensure that the human rights of persons with disabilities are respected, protected, and promoted, and hence each theme can be covered by several articles or principles. For example, the right to legal capacity—that is, the right to make decisions and have those decisions respected—could refer to decisions about things that affect a person’s day-to-day life as well as decisions about things that affect the person’s overall care, overlapping with the right to participation in the design and delivery of services and support options.

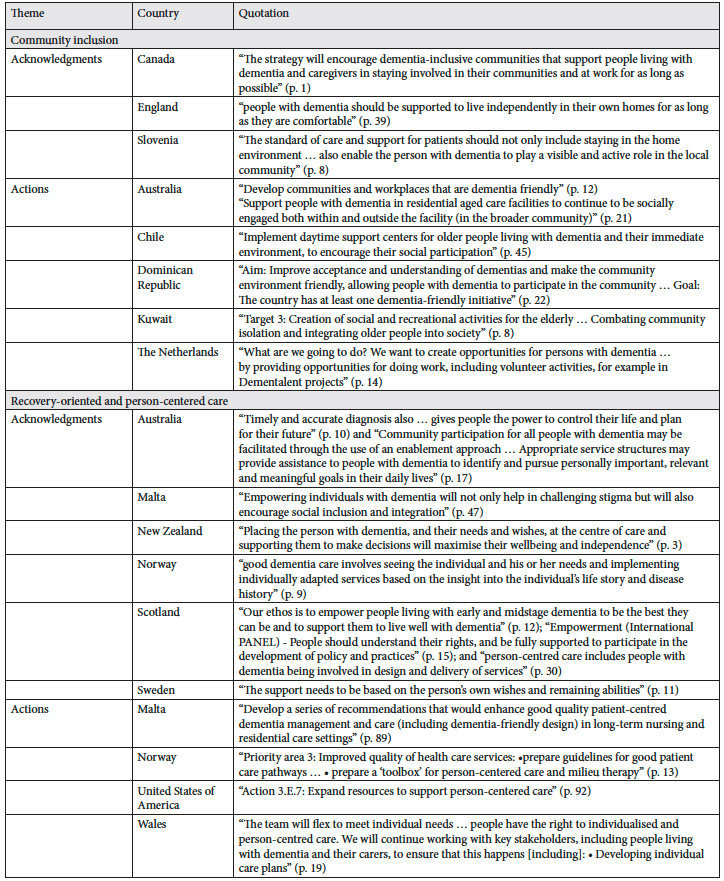

Community inclusion. People with dementia have the right to live and the right to make the same choices in life as others. They are entitled to choose where and with whom they live and to have the same access to community services as the general public.[29] Article 19 (living independently and being included in the community) of the CRPD, among others, encompasses this right.[30] We included the related term “dementia-friendly communities/societies” in our content searching. Thirty-nine (97.5%) of the plans examined mentioned community inclusion, primarily though the provision of dementia-friendly communities. Several of the references to community inclusion were recognitions that people with dementia should be included in the community and should be supported in this endeavor. To achieve this, many plans stated that dementia-friendly communities would be created in the wider community.

People with dementia should be able to participate in social and community life. (Austria)[31]

Develop dementia friendly communities, where all aspects of the community’s built environment and approaches are dementia friendly, inclusive, promote respect and acceptance and enable participation. (Australia)[32]

Recovery-oriented and person-centered care. Recovery-oriented care means enabling people with dementia to gain or regain control over their lives, have hope for the future, and live a life meaningful to them.[33] It relates to the conceptual framework of personal recovery, which encompasses five themes: connectedness, hope, identity, meaningfulness, and empowerment.[34] Person-centered care refers to using a collaborative approach with the person concerned and incorporating the person’s opinions, voices, and personal histories into their care.[35] While both of these concepts clearly overlap, there are differences between the two. Although no specific article of the CRPD encompasses recovery-oriented and person-centered care, article 26 (habilitation and rehabilitation) arguably comes closest regarding recovery-oriented approaches.[36] Additionally, article 3 (general principles) aligns with person-centered principles (“respect for inherent dignity, individual autonomy including the freedom to make one’s own choices, and independence of persons … respect for difference and acceptance of persons with disabilities”).[37] Within this theme, we also searched for the following synonyms: “agency,” “dignity,” and “empowerment.” This theme was mentioned by 31 (77.5%) plans. Several countries provided explicit actions relating to recovery-oriented and person-centered approaches to dementia care.

Support should be tailored to the individual person with dementia and their carers, not to managers of different services or health services. (Slovenia)[38]

Develop an efficient and coordinated system of care for people with dementia … under a network approach (including long-term care), to provide person-centered and integrated care. (Dominican Republic)[39]

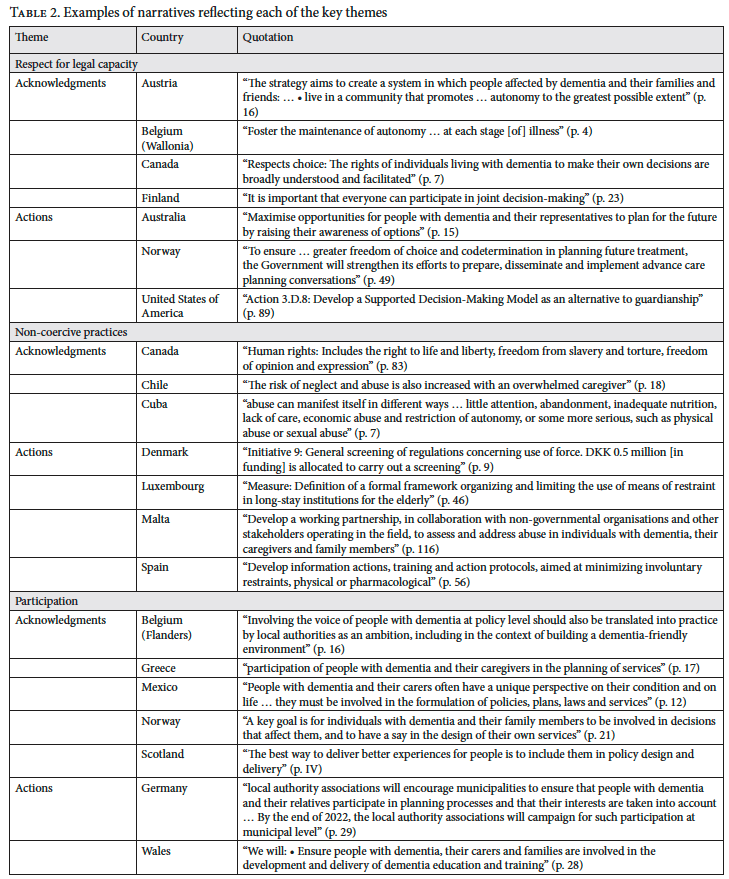

Respect for legal capacity. Respect for legal capacity is defined as the right to make decisions for oneself and to have one’s decisions respected by others; it is primarily represented by article 12 of the CRPD (equal recognition before the law).[40] It is the backbone of other human rights and includes the right to be recognized as a person before the law and have one’s decisions legally respected.[41] We searched for keywords such as “legal capacity,” “autonomy,” “supported decision-making,” and “advance care planning.” Overall, 28 (78%) plans mentioned legal capacity. Several included the word “autonomy” in the overarching aims of their plans, demonstrating that governments and ministries acknowledge that people with dementia should be in control of and have freedom of choice in their lives.

The vision of this plan … [is that] people with dementia and their caregivers receive the quality care and support they need with dignity, respect, autonomy, and equity. (Dominican Republic)[42]

Some countries also demonstrated their awareness that supporting people with dementia and their care partners in maintaining autonomy and legal capacity is protected by their own laws and international regulations.

As a signatory to the Glasgow Declaration, the Welsh Government has previously committed to promote the rights, dignity and autonomy of people living with dementia. (Wales)[43]

Regarding specific actions to promote and protect the right to legal capacity, countries referred to ensuring that measures for advanced care planning and supported decision-making would be provided.

Objective delivery … i. Work towards the development of advance care directives. (Malta)[44]

Non-coercive practices. Coercive care practices are those that go against the wishes of the person receiving care, such as forced admission to services, forced treatment, seclusion, and mechanical, physical, and chemical restraints.[45] They are also practices that are undertaken without the person’s consent. The CRPD protects the rights to freedom from coercion with the following articles: liberty and security of person (article 14), freedom from torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment (article 15), and freedom from exploitation, violence, and abuse (article 16).[46] Coercion also encompasses a denial of legal capacity.[47] Twenty-four plans (60%) mentioned coercive and non-coercive practices; however, few plans provided specific actions to ensure that coercive methods are not used within dementia care. Instead, there was mostly a recognition that people with dementia have been and continue to be subjected to harmful practices.

Dementia will eventually impair the ability to make informed decisions and provide consent. There may therefore be … uncertainty as to whether a decision is voluntary or if the person displays opposition towards a measure. If the person displays opposition, the measure is considered coercive. (Norway)[48]

8.5. Legal, social and financial assistance to prevent abuse, violence or neglect in the care of the person with dementia. (Mexico)[49]

Participation. Participation refers to people living with dementia (and their care partners) being involved in societal decisions, such as the design and delivery of services and policies regardless of expertise.[50] It also involves the concept of citizenship: having rights, responsibilities, and meaningful opportunities within the wider community.[51] We included “citizenship” as our synonym for this theme. It is guaranteed by article 29 (participation in political and public life) and article 30 (participation in cultural life, recreation, leisure, and sports) of the CRPD.[52] Twenty-four plans (60%) referred to or specifically mentioned participation.

According to Article 29 of the [CRPD], people with dementia should be able to play an active role in shaping public affairs … [and] given the opportunity to review the relevance and appropriateness of local planning processes from their perspective … This will allow people with dementia to be involved … in the planning of social spaces. (Germany)[53]

Stakeholder participation in policy development and legislative changes concerning persons with dementia is ensured through a consultation portal … What will the situation be in 2030? Active participation of persons with dementia in discussions and decisions concerning this patient group. (Iceland)[54]

Nineteen countries (47.5%) declared that people with lived experience (both persons with dementia or their care partners) had been involved in the design of the national dementia plan, and some specifically stated how they will continue to involve this population in the implementation of plans.

The national action plan for dementia was developed … [with] relevant actors in the field, citizens with dementia, their relatives, and experts and health professionals. (Denmark)[55]

Table 2 shows further examples of how governments incorporated human rights and the CRPD into their national dementia plans.

Discussion

This was the first in-depth review of how human rights have been addressed in national dementia plans. Many plans addressed some aspects of basic human rights for people with dementia; in particular, community inclusion was covered in all except one of the plans, and most mentioned developing dementia-friendly communities to achieve this. Perhaps these human rights aspects are easier for governments to promote for people with dementia. Concerningly, many plans did not adequately include non-coercive practices or participation, and the CRPD itself went unmentioned in almost 75% of the plans, despite most of these countries having either signed or ratified the convention. While this lack of specific mention of the CRPD does not on its own indicate that the plans overlooked certain human rights for people with dementia, our review of the content relating to the human rights principles in the CRPD indicates that many plans did not align well with human rights standards. This is vitally important given growing concerns over the human rights of people with dementia. It also suggests a strong need for multisectoral action to protect and promote the human rights of persons with dementia in both policy and practice.

Although our findings suggest that the CRPD may not have been considered when governments developed their plans, our review is also consistent with the work of Rasita Vinay and Nikola Biller-Andorno, who found that social and cultural rights, such as community inclusion and recovery-oriented and person-centered care, were the foundations of national dementia plans.[56] While advanced care planning, increased dementia awareness, and holistic and individualized care were principles strongly considered in the eight plans they reviewed, the provision of alternative care to acute hospitalization was mentioned only sporadically.[57] Our review, alongside that of Vinay and Biller-Andorno, contrasts with the work of Suzanne Cahill, who found that political and civil rights, such as freedom from coercion, were more likely than social and cultural rights to be included in plans.[58] Both reviews, as well as our own, found that governments have placed emphasis on respect and dignity, although our analysis showed that these terms tended to be used in descriptions around what people with dementia are entitled to rather than specific actions to ensure that these needs are met.

It is important to note that our analysis was more extensive than the other two reviews; we took a comprehensive approach by using the CRPD as a whole rather than using selected items. Additionally, both of these past reviews were of a much smaller scale in comparison to ours: Vinay and Biller-Andorno reviewed eight plans, and Cahill examined ten.[59] Perhaps these reviews were smaller than ours due to the time of their completion. Our review was conducted close to the end of WHO’s global action plan target deadlines, whereas the previous reviews were conducted closer to the beginning of the global action plan. Nonetheless, our assessment has revealed similar findings to those of the previous studies, especially when considering that each country tailored its plan to meet its context-specific needs, and therefore it would be expected that visions for the plans and subsequent actions would differ somewhat.

Furthermore, we found that acknowledgments and actions relating to increasing awareness and reducing stigma to achieve community inclusion for people living with dementia were consistently included in national dementia plans, a finding also noted by previous reviews.[60] This is important because stigma and beliefs around dementia are some of the main contributors to human rights denials for people living with dementia.[61] Additionally, our results showed that although participation was mentioned in 60% of the analyzed plans, actions to ensure that this became a part of standard practice were few and far between. This supports the claim by Tim Schmachtenberg et al. that the participation of persons with dementia in planning activities and policies is needed, but in practice is lacking.[62] Our findings also support the recommendations of Nadia Boeree et al., who argue that policymakers must collaborate with people with dementia and their care partners in the development, execution, and evaluation of national dementia plans because it would enhance their effectiveness and overall usefulness.[63] They also argue that without the involvement of people with lived experience, any of the benefits that materialize from a plan’s implementation would not be felt by the people who should benefit most.[64] This echoes the claim that there are considerable gaps between the goals and visions of government policies and the lived experiences of those with dementia.[65] From a human rights-based point of view, the participation of people with dementia (and their care partners) in the design and delivery of national dementia plans is a fundamental right in accordance with the CRPD.[66]

Limitations

To reduce the risk of reviewer bias, each plan was assessed by at least two independent researchers. Additionally, we used publicly available data. That said, not all plans that have been launched were publicly accessible, meaning that we were unable to access eight plans. Moreover, we were unable to translate a further two. The plans missing from our analysis were mainly from the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Pacific WHO regions. Moreover, in order to include as many plans as possible in our review, we relied on a translation website powered by Google Translate rather than translating and then back-translating ourselves; as a result, the translations may have inaccuracies or misinterpretations or may have missed content. Finally, some of the plans included in our review had already, or have since, expired, meaning that their implementation period was over. However, at the time of searching, the included plans were still the most recent plan for those countries, and being publicly available, we chose to include them in the review.

Future directions

Since the completion of our review, several countries—for example, Australia, Brazil, Malta, and Uruguay—have produced new national dementia plans.[67] Further research should be conducted to investigate whether these new plans have a human rights focus, as well as whether future plans of the countries included in this review showcase any changes in their human rights content. Additionally, future research could examine the implementation of national dementia plans to assess the extent to which the actions outlined in the plans have been achieved in practice. This research could refer to article 4 of the CRPD, which relates to the general obligations of countries that have ratified the convention. Finally, future work should consider developing a global report on good practice in human rights in dementia care.

Implications

There are substantial implications for policy and practice following our review. First, the results can be used by WHO, ADI, and Alzheimer Europe, among national governing bodies, to advocate for a stronger human rights focus within plans to ensure the protection and promotion of the rights of people with dementia. This review supports WHO efforts to monitor progress on the global action plan targets, as well as ADI efforts to regularly report on the global picture of national dementia plans. ADI recently called for an extension of WHO’s global action plan targets to 2035 in its latest From Plan to Impact report.[68] The current target is for 146 countries to have a national dementia plan by 2025—and yet, as of ADI’s 2024 report, only 38 plans were currently in place, while others had expired and yet others did not have funding for their implementation.[69] Because none of the global targets is on track to be reached by 2025, WHO member states recently discussed a potential extension of the global action plan at the 156th session of the Executive Board.[70] Our review highlights where governments are falling short in complying with the CRPD and indicates how future plans can become more human rights focused.

Policy commitments should not remain mere paper promises—they should be actively implemented with clear accountability measures. Countries are required to report to the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities every four years on the measures taken to respect, protect, and promote the rights of persons with disabilities, and it is important that this process also include reporting on the actions taken to safeguard the rights of persons with dementia. At a national level, mechanisms such as national human rights groups, health services (including mental health services), and care quality commissions could integrate the monitoring of dementia-related human rights into their existing functions. Moreover, national and international nongovernmental organizations such as ADI and organizations of persons with disabilities such as Dementia Alliance International can play a pivotal role in monitoring and ensuring accountability.

Conclusion

This review systematically assessed the human rights content of national dementia plans. We found that nearly all of these plans covered basic human rights, especially with regard to the inclusion of people with dementia within the community. However, many plans did not sufficiently align with human rights standards, including the CRPD. There was a lack of specific actions regarding non-coercive practices and ensuring the participation of people with dementia in the design and delivery of services and policies that affect them. This review also has implications for the rights of people with dementia. Significant improvements are needed to guarantee the human rights of people with dementia; therefore, governments can use our findings to better understand the rights of their citizens with dementia and identify actions and frameworks to improve protections for them. Additionally, people with dementia can be encouraged to participate in the implementation of current plans, as well as the design and delivery of future ones. We join calls for a multisectoral effort to be implemented to guarantee the human rights of persons with dementia.

Briony Harden is a PhD candidate based at the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, Disability and Human Rights at the Institute of Mental Health, University of Nottingham, England.

Yinuo Mao is a master’s graduate from the Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, United States.

Justin Weiss is a master’s graduate from the Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, United States.

Selina Hsuan is a master’s graduate from the Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, United States.

Orii McDermott is a senior research fellow based at the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, Disability and Human Rights at the Institute of Mental Health, University of Nottingham, England.

Michelle Funk is head of the Policy, Law and Rights Unit in the Department of Mental Health and Substance Use at the World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Natalie Drew is a technical officer in the Policy, Law and Rights Unit in the Department of Mental Health and Substance Use at the World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Katrin Seeher is a mental health specialist in the Brain Health Unit in the Department of Mental Health and Substance Use at the World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Tarun Dua is head of the Brain Health Unit in the Department of Mental Health and Substance Use at the World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Martin Orrell is a professor of aging and mental health based at the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, Disability and Human Rights at the Institute of Mental Health, University of Nottingham, England.

Please address correspondence to Briony Harden. Email: briony.harden@nottingham.ac.uk.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2025 Harden, Mao, Weiss, Hsuan, McDermott, Funk, Drew, Seeher, Dua, and Orrell. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

[1] M. Donnelly, “Deciding in Dementia: The Possibilities and Limits of Supported Decision-Making,” International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 66/101466 (2019); E. Mariani, M. Vernooij-Dassen, R. Koopmans, et al., “Shared Decision-Making in Dementia Care Planning: Barriers and Facilitators in Two European Countries,” Aging and Mental Health 21/1 (2017).

[2] S. J. Ralph and A. J. Espinet, “Use of Antipsychotics and Benzodiazepines for Dementia: Time for Action? What Will Be Required before Global De-Prescribing?,” Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice 18/6 (2019); C. Øye and F. F. Jacobsen, “Informal Use of Restraint in Nursing Homes: A Threat to Human Rights or Necessary Care to Preserve Residents’ Dignity?,” Health 24/2 (2020); L. Steele, R. Carr, K. Swaffer, et al., “Human Rights and the Confinement of People Living with Dementia in Care Homes,” Health and Human Rights 22/1 (2020).

[3] Steele et al. (see note 2); L. Steele, K. Swaffer, L. Phillipson, and R. Fleming, “Questioning Segregation of People Living with Dementia in Australia: An International Human Rights Approach to Care Homes,” Laws 8/3 (2019).

[4] E. V. Gerritzen, G. Kohl, M. Orrell, and O. McDermott, “Peer Support Through Video Meetings: Experiences of People with Young Onset Dementia,” Dementia 22/1 (2023); C. Giebel, C. Eastham, J. Cannon, et al., “Evaluating a Young-Onset Dementia Service from Two Sides of the Coin: Staff and Service User Perspectives,” BMC Health Services Research 20/1 (2020); E. Breuer, E. Freeman, S. Alladi, et al., “Active Inclusion of People Living with Dementia in Planning for Dementia Care and Services in Low- and Middle-Income Countries,” Dementia 21/2 (2022).

[5] World Health Organization, Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia 2017–2025 (World Health Organization, 2017), p. 4.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, G.A. Res. 61/106 (2006); World Health Organization (2017, see note 5); S. Cahill, Dementia and Human Rights (Policy Press, 2018).

[8] United Nations, “Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD),” https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html.

[9] Alzheimer’s Disease International, From Plan to Impact VII: Dementia at a Crossroads (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2024).

[10] F. Sun, E. Chima, T. Wharton, and V. Iyengar, “National Policy Actions on Dementia in the Americas and Asia-Pacific: Consensus and Challenges,” Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 44 (2020).

[11] Alzheimer Europe, European Dementia Monitor 2017: Comparing and Benchmarking National Dementia Strategies and Policies (Alzheimer Europe, 2017); Alzheimer Europe, European Dementia Monitor 2020: Comparing and Benchmarking National Dementia Strategies and Policies (Alzheimer Europe, 2020); Alzheimer Europe, European Dementia Monitor 2023: Comparing and Benchmarking National Dementia Strategies and Policies (Alzheimer Europe, 2023); Cahill (see note 7); R. Vinay and N. Biller-Andorno, “A Critical Analysis of National Dementia Care Guidances,” Health Policy 130 (2023).

[12] Alzheimer Europe (2023, see note 11).

[13] S. Elo and H. Kyngäs, “The Qualitative Content Analysis Process,” Journal of Advanced Nursing 62/1 (2008).

[14] Ibid.

[15] World Health Organization, “WHO MiNDbank: More Inclusiveness Needed in Disability and Development,” https://extranet.who.int/mindbank/.

[16] Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (see note 7).

[17] United Nations, “Member States,” https://www.un.org/en/about-us/member-states.

[18] DocTranslator, https://www.onlinedoctranslator.com/en/translationform.

[19] Alzheimer’s Disease International and Dementia Alliance International, Access to CRPD And SDGs by Persons with Dementia (Alzheimer’s Disease International and Dementia Alliance International, 2016).

[20] World Health Organization, “WHO QualityRights,” https://qualityrights.org/.

[21] World Health Organization, Guidance on Community Mental Health Services: Promoting Person-Centred and Rights-Based Approaches (World Health Organization, 2021).

[22] United Nations, “Member States” (see note 17).

[23] Alzheimer’s Disease International, “Positive Global Developments for National Dementia Plans” (March 21, 2023), https://www.alzint.org/news-events/news/positive-global-developments-for-national-dementia-plans/.

[24] Scottish Government (Scotland), Dementia in Scotland: Everyone’s Story (2023), https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/sites/default/files/2023-06/Scotland%20National%20Dementia%20Strategy%202023%20-%20Everyone%27s%20Story.pdf; Wallonia Government (Belgium), Le Programme d’Actions Alzheimer Wallon (The Alzheimer Wallon Action Program) (2010), https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/Wallonia%20Alzheimer%20Plan%202010.pdf.

[25] Department of Health and Aged Care (Australia), National Framework for Action on Dementia 2015–2019 (2015), https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national-framework-for-action-on-dementia-2015-2019.

[26] Wallonia Government (Belgium) (see note 24); Flemish Ministry of Welfare, Public Health and Family (Belgium), Dementieplan 2021–2025 (Dementia Plan 2021–2025) (2021), https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/sites/default/files/2022-11/Flanders%20Dementia%20Plan%202021%20-%202025.pdf.

[27] Ministry of Social Affairs and Health (Finland), National Programme on Ageing 2030: For an Age-Competent Finland (2020), https://www.alzint.org/u/Finland-National-Programme-on-Ageing-2030.pdf; Ministry of Public Health (Qatar), Qatar National Dementia Plan 2018–2022: Summary (2018), https://www.alzint.org/u/Qatar-National-Dementia-Plan_compressed-10.pdf.

[28] World Health Organization (2021, see note 21).

[29] Ibid.

[30] Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (see note 7).

[31] Federal Ministry Labour, Social Affairs, Health and Consumer Protection (Austria), Dementia Strategy: Living Well with Dementia (2015), https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/sites/default/files/2021-09/Austrian%20Dementia%20Startegy%202015%20-%20English%20version_9.pdf, p. 7.

[32] Department of Health and Aged Care (Australia) (see note 25), p. 12.

[33] World Health Organization (2021, see note 21).

[34] M. Leamy, V. Bird, C. Le Boutillier, et al., “Conceptual Framework for Personal Recovery in Mental Health: Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis,” British Journal of Psychiatry 199/6 (2011).

[35] S. Terada, E. Oshima, O. Yokota, et al., “Person-Centered Care and Quality of Life of Patients with Dementia in Long-Term Care Facilities,” Psychiatry Research 205/1–2 (2013).

[36] Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (see note 7).

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ministry of Health (Slovenia), Strategija Obvladovanja Demence V Sloveniji Do Leta 2020 (Dementia Management Strategy in Slovenia until 2020) (2016), https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/Slovenia%20National%20Dementia%20Strategy.pdf, p. 13.

[39] Ministry of Public Health (Dominican Republic), Plan de Respuesta a las Demencias en la República Dominicana 2020–2025 (Dementia Response Plan in the Dominican Republic 2020–2025) (2020), https://www.alzint.org/u/Dominican-Republic-National-Dementia-Plan.pdf, p. 25.

[40] Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (see note 7); World Health Organization (2021, see note 21).

[41] Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, General Comment No. 1, UN Doc. CRPD/C/GC/1 (2014).

[42] Ministry of Public Health (Dominican Republic) (see note 39), p. 19.

[43] Welsh Government (Wales), Dementia Action Plan for Wales 2018–2022 (2018), https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/Wales%20Dementia%20Action%20Plan%202018-2022.pdf, p. 3.

[44] Parliamentary Secretariat for Rights of Persons with Disability and Active Ageing (Malta), Empowering Change: A National Strategy for Dementia in the Maltese Islands 2015–2023 (2015), https://www.alzint.org/u/Malta-National-Dementia-Strategy-2015-2023.pdf, p. 61.

[45] World Health Organization (2021, see note 21).

[46] Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (see note 7).

[47] World Health Organization (2021, see note 21)

[48] Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services (Norway), Demensplan 2025 (Dementia Plan 2025) (2020), https://www.alzint.org/u/Norway-demensplan-2025.pdf, p. 79.

[49] National Institute of Geriatrics and Secretary of Health (Mexico), Plan de acción Alzheimer y otras demencias México (Plan of Action for Alzheimer and Other Dementias in Mexico 2014) (2014), https://www.alzint.org/u/Mexico-National-Dementia-Plan_alzheimer_WEB.pdf, p. 62.

[50] World Health Organization (2021, see note 21).

[51] D. O’Connor, M. Sakamoto, K. Seetharaman, et al., “Conceptualizing Citizenship in Dementia: A Scoping Review of the Literature,” Dementia 21/7 (2022).

[52] Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (see note 7).

[53] Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth and Federal Ministry of Health (Germany), Nationale Demenzstrategie (National Dementia Strategy) (2020), https://www.alzint.org/u/Germany-2020-07-01_Nationale_Demenzsstrategies.pdf, p. 28.

[54] Ministry of Health (Iceland), Aðgerðaáætlun um þjónustu við einstaklinga með heilabilun (Action Plan for Services to Persons with Dementia) (2020), https://www.alzint.org/u/Iceland-Adgerdaaaetlun-um-thjonustu-vid-einstaklinga-med-heilabilun.pdf, p. 8.

[55] Danish Ministry of Health (Denmark), Et trygt og værdigt liv med demens: National Demenshandlingsplan 2025 (A Safe and Dignified Life with Dementia: National Action Plan 2025) (2017), https://alzheimer-europe.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/Denmark%20National%20Action%20Plan%202025.pdf, p. 7.

[56] K. Swaffer, “Addressing the Issue of Human Rights in Dementia,” Gerontology and Society 39/154 (2017); Vinay and Biller-Andorno (see note 11).

[57] Vinay and Biller-Andorno (see note 11).

[58] Cahill (see note 7); Vinay and Biller-Andorno (see note 11).

[59] Vinay and Biller-Andorno (see note 11); Cahill (see note 7).

[60] Sun et al. (see note 10); S. Chow et al., “National Dementia Strategies: What Should Canada Learn?,” Canadian Geriatrics Journal 21/2 (2018).

[61] S. M. Benbow and D. Jolley, “Dementia: Stigma and Its Effects,” Neurodegenerative Disease Management 2/2 (2012).

[62] T. Schmachtenberg, J. Monsees, and J. R. Thyrian, “Structures for the Care of People with Dementia: A European Comparison,” BMC Health Services Research 22/1 (2022).

[63] N. C. Boeree, C. Zoller, and R. Huijsman, “The Implementation of National Dementia Plans: A Multiple-Case Study on Denmark, Germany, and Italy,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18/19 (2021).

[64] Ibid.

[65] Cahill (see note 7).

[66] Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (see note 7).

[67] Alzheimer’s Disease International (2024, see note 9).

[68] Ibid.

[69] World Health Organization (2017, see note 5); Alzheimer’s Disease International (2024, see note 9).

[70] World Health Organization, “EB156,” https://apps.who.int/gb/e/e_eb156.html.