Temporal Accountability and Taiwan’s National Health Insurance System

EXPLORING ACCOUNTABILITY FOR HEALTH RIGHTS Vol 27/2, 2025, pp. 107-119 PDF

Tsung-Ling Lee and Chien-Liang Lee

Abstract

Accountability is central to human rights, yet it has varied interpretations across contexts. Conventionally, accountability denotes blame and punishment or emphasizes hierarchical relationships between claim holders and duty bearers. However, accountability cannot be an episodic event. In health governance, continuous and iterative improvements are required to reflect changing social, economic, and political circumstances. Accordingly, we define “temporal accountability” as an institutional design that incorporates time-bound obligations for implementing corrective actions and remedial measures. Through a case study of Taiwan’s Constitutional Court decision on expatriate residents’ financial contributions, we analyze temporal accountability in action and draw broader lessons for human rights accountability, proposing measurable indicators and guiding principles of temporal accountability.

Introduction

Universal health coverage is a cornerstone of the right to health, positioning health systems as foundational social institutions that drive equality of opportunity.[1] Accountability—central to democracy and human rights—is often equated with political responsibility and, conventionally, with blame or punishment.[2] However, in practice, liberal democracies do not automatically guarantee this form of accountability, nor do missteps always yield political consequences. Understanding how accountability manifests within democratic contexts requires close examination of the dynamic interactions among institutional actors such as courts, parliaments, executives, civil society organizations, the public, the media, and human rights commissions. These interactions collectively shape access to health care and undergird the financial sustainability and fairness of health systems.

Through a case study on Taiwan, this paper contributes to the global dialogue on accountability, drawing generalizable lessons for creating sustainable and equitable health systems. Specifically, we examine how decisions about fair health financing evolve over time in response to changing societal needs and economic circumstances, capturing the operations of accountability mechanisms in practice as societies work to ensure that health financing arrangements remain both equitable and sustainable.

Accountability is a critical feature of health rights and yet it has various conceptualizations. Judicial accountability, for instance, focuses on legality and due process—emphasizing review mechanisms and remedies for individuals and communities who have been unlawfully harmed. As discussed in the next section, accountability relationships can be further classified as horizontal or vertical. Building on these frameworks, we identify temporal accountability as an important yet often overlooked dimension in health governance. This lens captures how institutional actors interact to address financial sustainability and fairness in health systems as social, economic, and political circumstances evolve over time.

Accordingly, we define “temporal accountability” as an institutional design that builds time-bounded obligations for review, disclosure, and corrective action into the accountability cycle. Our approach builds on human rights accountability, which consists of three components: monitoring, reviewing, and remedial action.[3] We regard accountability as a continuous process that includes monitoring and iterative improvements through adapting policies to reflect evolving social, political, and economic realities. This understanding of accountability relies on institutional interactions—both formal and informal—and allows for assessing how states uphold health care-related human rights obligations. As we demonstrate, improvements occur iteratively, shaped by the perspectives and actions of diverse institutional actors.

We situate the discussion within liberal democracies, recognizing that health systems differ significantly across countries. Democratic deliberation is conventionally believed to serve as a vehicle for meeting health needs fairly in a democracy. In democracies, political disagreements can reveal different values, perspectives, and interests that are negotiated and interrogated to arrive at commonly acceptable—and therefore (arguably) equitable—outcomes.[4] However, majoritarian decision-making may not adequately consider minority groups’ health needs or address the specific circumstances of vulnerable populations. Moreover, countries with well-functioning health systems increasingly face challenges of financial sustainability due to demographic shifts and changing economic circumstances. Balancing sustainable health financing fairly in the face of these evolving pressures is a considerable challenge that requires accountability mechanisms capable of adapting over time.

To explore how accountability mechanisms address this challenge in practice, we examine Taiwan’s experience. We conduct a doctrinal analysis of the Constitutional Court decision 111-Hsien-Pan-19, issued in 2022, and the National Health Insurance Act and its Enforcement Rules. We triangulate this with National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA) administrative notices, legislative records between 1996 and 2024, and major media coverage on policy changes. Tracing processes, we map the sequence of interactions among judicial, legislative, executive, and the public and link each to policy adjustments. We also descriptively summarize utilization and fiscal data from the media and NHIA, calculated at US$1 = NT$32 as of July 2025. Because available NHIA datasets are impartial, we relied on figures released by the NHIA and legislative comments. Since we did not conduct interviews because of resource constraints, our findings should be interpreted as a theory-building case analysis rather than causal inference.

This study relies on administrative and legal documents and publicly reported data to identify the interactions among various accountability mechanisms. The fiscal figures contained in this paper are descriptive rather explanatory accounts of decision-making processes.

The paper proceeds as follows: The first section outlines the accountability framework that guides our analysis of Taiwan’s case. The second section provides background on the Constitutional Court’s landmark ruling and examines its broader policy implications. The third section evaluates how our case study aligns with temporal accountability principles. The paper closes with a conclusion.

Accountability

Conceptualizing accountability in health systems

There are several conceptualizations of accountability. Accountability is commonly understood as a relational concept, characterized by either vertical or horizontal relationships.[5] Vertical accountability refers to the relationship between rights holders and those in formal positions of authority.[6] Horizontal accountability refers to relationships among state actors with formal responsibilities to provide explanations.[7]

Within health systems specifically, accountability takes on heightened importance as financial constraints intensify. Resilience-focused health systems emphasize responding efficiently to external shocks but do not necessarily prioritize fair outcomes.[8] Improving health systems focus on generating and applying evidence to improve health care delivery and reduce inequalities in health access yet often do so without stakeholder participation.[9]

From a human rights perspective, accountability represents “the formal and informal processes, norms, and structures, particularly in a democratic system that demands power holders or people in authority account for their decisions and actions and remedy and failures in delivering their duties.”[10] While accountability is central to human rights, it can become invisible or marginal, deceptively familiar yet with various conceptualizations across different contexts.[11] Conventionally seen as blame and punishment, accountability can serve as a form of deterrence, paradoxically preventing governments from taking action in liberal democracies because of immediate political consequences or perceived administrative burdens.

However, Paul Hunt, former Special Rapporteur on the right to health, advocates for a broader view: accountability as a process in which successful practices are identified and ineffective ones are adjusted.[12] This constructive approach emphasizes ongoing monitoring, systematic evaluation, and continuous iterative improvement of health systems and policies.[13] This broader view of accountability moves beyond notions of fault-finding and focuses instead on transparent mechanisms that allow stakeholders to track progress, identify shortcomings, and make necessary adjustments to ensure that reasonable balances between competing interests are fairly achieved and maintained over time. Importantly, this conceptualization recognizes accountability as an ongoing institutional process essential to rights-based health care governance.

This conceptualization draws from Lynn Freedman’s constructive and relational accountability. As Freedman puts it, constructive accountability “is about developing a dynamic of entitlement and obligation between people and their government and within the complex system of relationships that form the wider health system, public and private.”[14] In a health system, relationships between stakeholders matter. They form the foundation of shared responsibility for ensuring health system functioning.

The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights’ General Comment 14—which provides an authoritative and comprehensive interpretation on the right to health—establishes and articulates an AAAQ framework that encompasses availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality, along with the cross-cutting principles of nondiscrimination, participation, transparency, and accountability.[15] These principles form the basis through which states are expected to respect, protect, and progressively fulfill their human rights obligations in the health domain.

Human rights accountability provides a valuable framework for advancing the various elements of health systems, including health equity, through a rights-based approach. This framework is particularly important because, as Lawrence Gostin observes, “The right to health would be all but meaningless without a powerful focus on equity. If governments had to ensure rights only for some but not for all, then the most marginalized and disadvantaged—the people who depend most on the right to health—would be left behind.”[16] To that end, universal health coverage serves as an expression of the right to health with equity at the center. This equity-centered design is essential for ensuring that all members of society contribute according to their financial capacity while receiving care according to their needs.

While universal health coverage gives expression to the right to health, operationalizing it can be challenging. As Lisa Forman observes, “Rights are inherently indeterminate, and their application to various problems must be worked afresh in contexts that textual formulations are likely to address only abstractly.”[17] This captures a key challenge in human rights: translating abstract principles into concrete action. In addition, health care governance must continuously adapt through regular review cycles—balancing competing values, responding to changing circumstances, incorporating stakeholder input, and establishing clear triggers for policy adjustments.

Temporal accountability

Temporal accountability addresses this challenge by contextualizing rights within specific circumstances and time frames, transforming abstract formulations into actionable steps that can be implemented, monitored, and adjusted. By embedding accountability mechanisms within defined time frames, it ensures that rights function as living principles—adapting to evolving contexts while maintaining normative force—rather than remaining aspirational statements. This approach recognizes that realizing rights requires ongoing cycles of evaluation, adjustment, and refinement, not episodic legislative or judicial acts.

Building on this foundation and recognizing that various meanings and concepts exist for accountability, we define “temporal accountability” as an institutional design that builds time-bound obligations for review, disclosure, and corrective action into the accountability cycle.[18] This process flows from courts to the legislature, the executive, civil society organizations, the public, and the media, and then back as feedback, transforming accountability from episodic “score-keeping” into an iterative process with mandated pacing. Unlike horizontal accountability that focuses on who holds whom to account, temporal accountability specifies when and how often actors must evaluate evidence, review, and adjust. We advance the temporal dimension of accountability to underscore how changes occur incrementally as societies attempt to solve complex social problems such as fair health financing in universal health coverage, rather than through sudden, dramatic shifts in response to evolving social and political climates.

Temporal accountability provides an analytic framework that expands on Freedman’s understanding of accountability as going beyond the conventional focus on relationships between actors and builds on Hunt’s broader perspective of accountability as more than blame and punishment. The temporal dimension matters because it reveals how accountability unfolds over time—or fails to—including when and how often actors must review, disclose, and correct their actions. This approach examines both scope (who is involved and what is covered) and timing (at what intervals or critical moments scrutiny occurs). It ensures that institutional mechanisms address ongoing challenges through sustained attention and iterative responses. In relation to contentious issues, such as health financing for universal health coverage, temporal accountability keeps relevant authorities answerable, continually adapting as circumstances evolve and new data emerge. This approach maintains transparency and responsiveness in managing complex health issues, reflecting the notion that fairness depends on socioeconomic context and the passage of time.

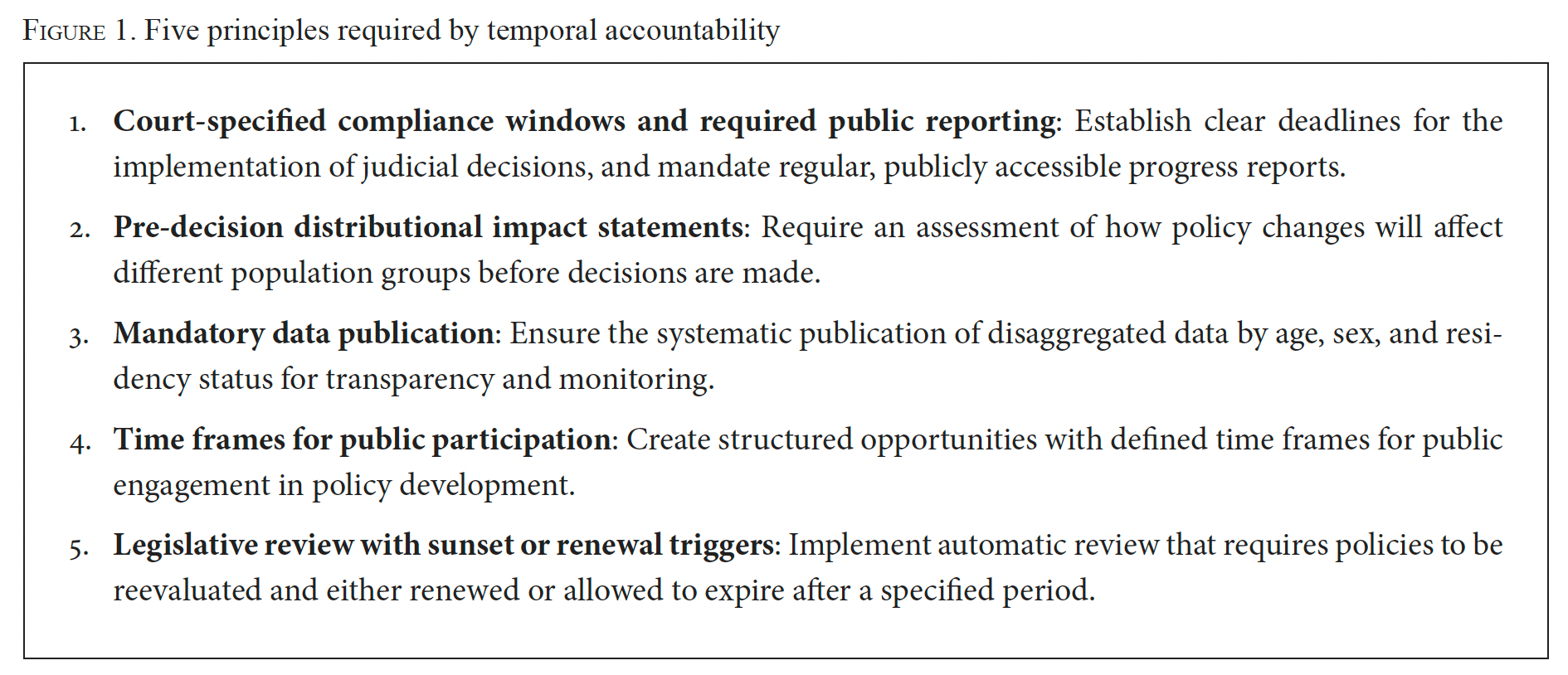

As we demonstrate in the third section, accountability emerges from overlapping institutional oversight, with continuous adjustments yielding responsive outcomes. However, its effectiveness depends on the quality and inclusivity of institutional interactions. We propose indicators to track progress, such as indicators for statutory deadlines, reporting frequency, disaggregated health care data, transparency, public participation, and legislative review.[19]

Case study

Ensuring a sustainable public health care system necessitates stable, reliable funding from all financially able participants. Yet in Taiwan, there is substantial debate among institutional actors concerning whether expatriates should be required to contribute to health premiums while living abroad. This debate does more than highlight differing perspectives—it is part of a complex web of accountability that fosters iterative improvement and aligns health policy with public expectations.

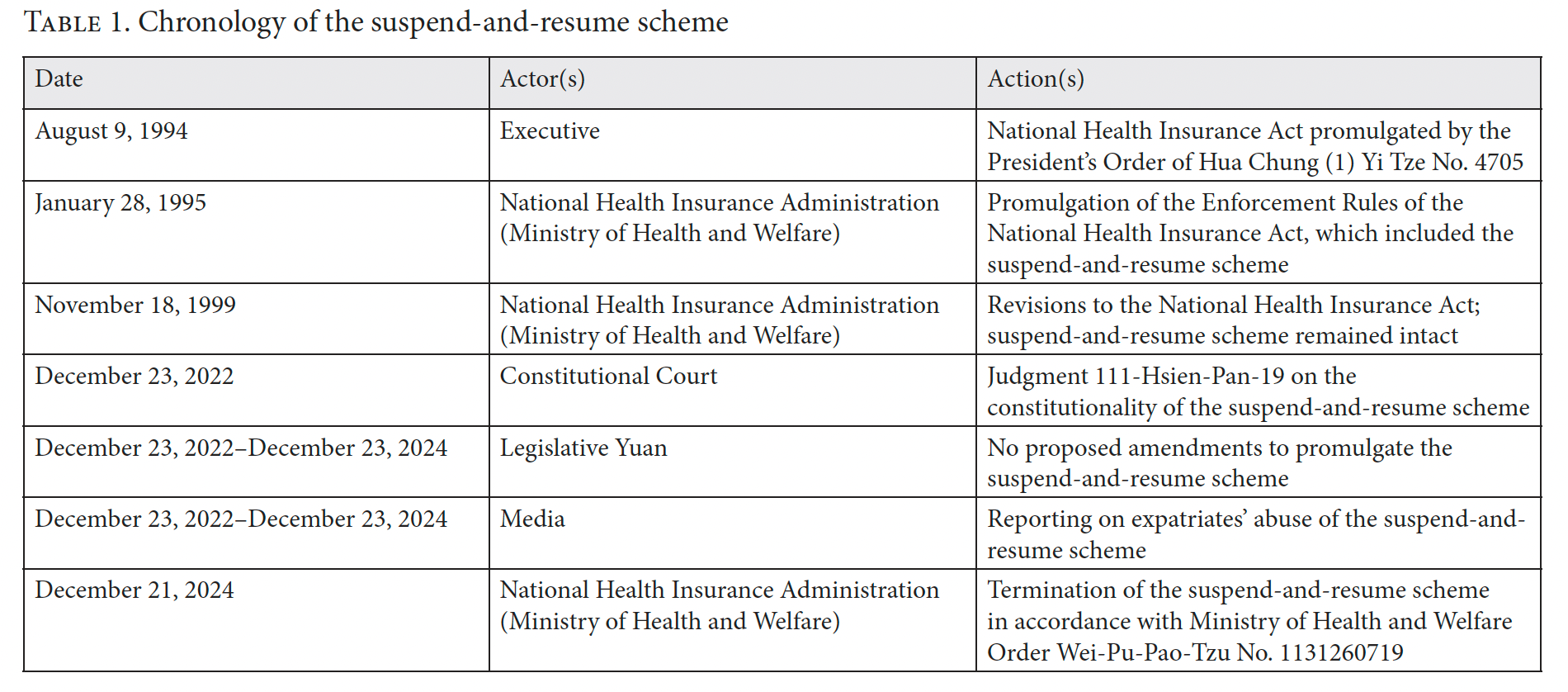

To understand how these accountability mechanisms work in practice, we examine a Taiwanese Constitutional Court case centering on a contentious health insurance policy known as the suspend-and-resume scheme. (See Table 1 for a chronological overview of the scheme.) This now-defunct scheme exempted long-term overseas residents from mandatory premium payments while abroad but reinstated these obligations upon their return—regardless of how long they stayed or whether they had alternative insurance coverage. This arrangement raised critical questions about fairness, equality, autonomy, and property rights. The exemption applied only to expatriates, creating unfairness for residents in Taiwan. Yet expatriates required to pay health premiums upon returning home also viewed the scheme as unfair. As we demonstrate below, fairness in health care emerges as both a relational and relative concept, highly dependent on one’s position within the system—underscoring the importance of accountability.

Prior to discussing the Constitutional Court case, we provide some background on Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (NHI) system, which illuminates how health policy reflects political choices.

Taiwan’s National Health Insurance system

Taiwan introduced its NHI system in 1995, replacing fragmented programs that covered less than 60% of the population. Now mandatory for nearly all residents, NHI covers 99% of people and includes almost all hospitals, most clinics, and a majority of pharmacies. The NHIA oversees this single-payer, state-run program. NHI offers broad coverage, including preventive, curative, dental, maternity, and elderly care, as well as traditional Chinese medicine. The average monthly premium is US$42 (5.17% of monthly income), less than South Korea (7%) and Japan (10%), both of which have similar systems.[20] Low-income households are exempt, while others pay 30%–100% of premiums based on occupation and income.[21]

Despite the efficient and wide coverage of the NHI system, financial challenges and long-term sustainability concerns threaten its continued operational viability.[22] Any proposed increases to health insurance premiums must receive formal approval from the Legislative Yuan (Parliament), a process that encounters significant political resistance due to the widespread unpopularity of premium increases among voters. While raising health premiums is essential for ensuring the financial stability and continued functioning of the insurance system, such proposals inevitably remain politically contentious and emotionally charged issues.[23] These tensions reflect deeper questions about how Taiwan’s democratic institutions balance the technical requirements of a sustainable health system with the political realities of democratic governance—questions that become clearer when examining the NHI system’s historical role in Taiwan’s political and economic development.

NHI system and democratization

In Taiwan, the national health system has played a crucial role in supporting the country’s democratization process and economic development.[24] Because health is recognized for its instrumental value—good health is a precondition for economic prosperity—the relationship between health and economic prosperity is particularly evident in Taiwan.[25] The NHI system has supported the country’s workforce through major economic transitions as Taiwan has evolved from an agricultural-based economy to a global hub of semiconductor manufacturing.[26] Similarly, the NHI system has facilitated the construction of a national identity and the cultivation of a sense of social solidarity during health crises, in particular during the COVID-19 pandemic.[27] The efficient health system has become a source of national pride, and its affordability and accessibility have enhanced the visibility of Taiwan’s global health diplomacy efforts.[28]

Taiwan’s national identity is shaped by its history and politics, with the NHI system central to building modern Taiwanese national consciousness. When Taiwan was under authoritarian rule, state health coverage mainly supported elites, leaving most citizens without adequate care. Former president Lee Teng-Hui, who oversaw the end of martial law, expanded health care access as part of the democratization process, leading to the 1995 National Health Insurance Act that guaranteed universal coverage. This strengthened both democracy and equality, ensuring universal access to affordable health care and enabling greater civic participation.

In addition, because health carries special moral significance due to its direct influence on individuals’ life opportunities, decisions regarding health care resource allocation have become matters of substantial public interest and have invoked intense societal debate in the country.[29] Thus, when the suspend-and-resume scheme was in effect, allowing Taiwanese citizens residing in China to return specifically to access health care resources—particularly amid increasing geopolitical tensions between Taiwan and China—it triggered widespread public outrage, prompting serious questions about fairness, equity, and shared responsibility in maintaining and sustaining the national insurance system.[30]

Expatriates’ health premiums exemption

While the National Health Insurance Act requires universal participation, the Enforcement Rules of the National Health Insurance Act (Enforcement Rules)—the accompanying administrative rules governing the implementation of the NHI—established a suspend-and-resume mechanism for Taiwanese citizens who lived overseas for more than six months.[31] This scheme allowed individuals to pause their health premium payments while abroad, benefiting approximately 210,000 Taiwanese living overseas.[32]

The suspend-and-resume mechanism originated under Taiwan’s authoritarian regime to benefit specific groups, including retired civil servants who had moved to the United States, by exempting them from ongoing premium contributions.[33] After democratization, the Enforcement Rules allowed ordinary citizens residing overseas for more than six months to suspend coverage and resume immediately upon return by paying three months of premiums. Those abroad for more than two years faced automatic suspension, along with a six-month waiting period and payment requirement.[34] NHIA data showed steadily increasing use by overseas residents, particularly for elective surgeries.[35]

Landmark Constitutional Court decision

While scholars had long criticized the suspend-and-resume scheme for violating equal protection, the Constitutional Court did not address it until 2022. The plaintiff in the case, a long-term resident of Japan, challenged the US$70 health premium requirement during her annual visits home, arguing that it violated her property rights, self-determination, and equal protection under the Constitution.

The court ruled that mandatory participation in the NHI system falls within the government’s social welfare responsibility.[36] However, it determined that such a policy must be enacted through Parliament, not solely by the NHIA, recognizing legislative scrutiny as essential for important health care decisions. In this regard, the ruling examined the constitutionality of articles 37(1) and 39 of the Enforcement Rules.

First, the Constitutional Court ruled that the suspend-and-resume scheme was unconstitutional because it had been adopted by way of an administrative ruling, basing its determination on the doctrine of Gesetzesvorbehalt (the principle that the authority to regulate must be grounded in statute for rights-relevant matters). This doctrine checks government power by requiring that significant decisions affecting citizens’ rights pass through the legislature, thereby establishing Gesetzesvorbehalt as a baseline for accountability in health care matters.

Second, the Constitutional Court reviewed the suspension mechanism using three principles enshrined in the R. O. C. Constitution: equal protection (article 7), property rights (article 15), and the right to self-determination in health risk management (管理自身健康風險之自主決定權, article 22). By introducing the concept of self-determination in health risks, the court highlighted the constitutional significance of health care and justified delegating related decisions to Parliament, enhancing accountability in Taiwan’s health care governance.

The court’s focus on the separation of powers highlighted the importance of accountability in health care governance by affirming that decisions affecting health care access are constitutional matters requiring democratic discussion. This intervention advanced Taiwan’s constitutional law by mandating legislative debate and public scrutiny for health care rights, emphasizing that these rights involve both personal and collective responsibilities best addressed through public discourse. While the court ruled that the scheme was unconstitutional on procedural grounds because it was promulgated by an administrative agency lacking the necessary authority, the court found the substance of the scheme constitutional. It determined that requiring expatriates to contribute health premiums upon returning to Taiwan violated no protected fundamental rights.

Significantly, by requiring formal legislation on issues that affect citizens’ health decisions, property rights, and health care resource distribution, the court elevated health matters into the realm of public consciousness and democratic discourse. The court also noted that compulsory health insurance promotes equality, where questions regarding fairness and nondiscrimination require parliamentary debate and oversight. Citing Gesetzesvorbehalt, the Constitutional Court set a two-year deadline for parliamentary debate to ensure democratic oversight of the scheme.

While the court did not specify which fundamental right underlies self-determination in managing health risks, this right connects to the broader right to health in international human rights law. Taiwan has voluntarily incorporated international human rights treaties into domestic law, providing an analytical framework to clarify this relationship: self-determination means personal autonomy over health care decisions, while the right to health covers wider legal claims, including social factors affecting health.

In our view, expanding the focus from self-determination to comprehensive health rights offers key normative advantages. First, it would clarify the contours of the right to health in Taiwan by recognizing that its realization depends on both government action and collective societal efforts. Second, since the right to health encompasses a legal entitlement to a functional health system—including sustainable health financing, equitable resource use, and a functional health care workforce—this broader interpretation would illuminate equality and nondiscrimination. It expands beyond self-determination and property rights to include the societal dimension of eliminating avoidable health inequalities.

This interpretation aligns with international standards, which understand the right to health as extending beyond medical care to include social factors such as better working conditions for health care professionals, strong government leadership, and oversight by human rights commissions. Although the Constitutional Court found that the suspend-and-resume scheme did not violate the right to self-determination under article 22 of the Constitution, the decision raises important questions about the broader right to participate in health policy development—a participatory right formally recognized in the Declaration of Alma Ata.[37]

Institutional interactions

Following the Constitutional Court ruling, the executive branch chose not to submit the suspend-and-resume scheme to Parliament.[38] The NHIA ended the scheme on December 23, 2024—the same day as the court’s deadline—mainly due to financial sustainability, not human rights.

Although controversial, the scheme had persisted for nearly 30 years due to protective institutional barriers. When the court framed health care access as a constitutional issue, it permitted new legislative and executive actions. The NHIA’s choice to terminate rather than amend the scheme addressed domestic and overseas residents’ unequal treatment but bypassed the democratic process the court intended.

However, the legislature took no action after the court’s ruling, despite having the authority to formally implement the scheme. Strong public opposition and fears of resource exploitation deterred parliamentarians. Even now, Parliament could promulgate the scheme, although involving legislators in health care decisions risks majoritarian outcomes that may overlook minority interests.

Temporal accountability and the suspend-and-resume scheme

This case study demonstrates how accountability emerges through interactions among the judiciary, legislature, and executive—each operating within distinct mandates yet forming an adaptive framework responsive to evolving societal expectations.

AAAQ analysis

Drawing from the international right to health as set out in General Comment 14, we examine some of the health rights features of the suspend-and-resume mechanism.[39]

Availability

Adequate health care availability depends on sufficient facilities, resources, and personnel. Taiwan’s suspend-and-resume mechanism in the NHI system raised concerns about the ability to maintain service levels, though its financial impact was minimal (1.18% of annual revenue).[40] Ending the scheme signaled a commitment to fairness and sustainable funding, but operational constraints—especially staff shortages and burnout—remain. Increased demand, such as returning overseas residents needing care, adds further strain. Ensuring both the financial and operational sustainability is vital for ongoing adequate health care access.

Accessibility

Accessibility consists of four dimensions: nondiscrimination, physical access, economic access, and information access. The suspend-and-resume mechanism led to discriminatory patterns, allowing overseas residents to pause payments but keep benefits, while domestic residents had to pay continuously. This created a two-tiered system privileging those abroad and undermining economic accessibility, as some could avoid supporting Taiwan’s health care costs yet still use affordable services—resulting in moral hazard, especially for costly elective procedures. Although NHIA shared data on overseas usage to inform discussion, this information lacked details on the scheme’s impact on marginalized groups, which is crucial for fair, evidence-based policy.

Acceptability

Acceptability in health services means respecting medical ethics, cultural appropriateness, gender, and confidentiality. Taiwan’s suspend-and-resume mechanism challenged ethical principles by allowing some people to pause contributions, undermining solidarity and fairness in the system. Media coverage of misuse heightened public concerns about equity and burden-sharing. Acceptability also includes health care workers’ rights; increased burdens from this mechanism raised further concerns, especially amid rising workplace violence and burnout.

Quality

Quality in health care requires scientifically appropriate services, skilled staff, approved medicines, proper equipment, safe water, and adequate sanitation. Although the suspend-and-resume mechanism did not directly impact clinical care, it indirectly affected system quality by influencing workforce sustainability. Consistent, high-quality care depends on sufficient, well-supported health workers. Operational challenges, such as fluctuating demand and workforce pressures, undermined quality standards and risked staff burnout. Quality also involves robust health financing, information systems, and governance. The suspend-and-resume scheme created financial uncertainties, threatening long-term investments in care quality. Sustainable and predictable funding is essential for ongoing service improvement.

In summary, although the suspend-and-resume scheme enabled some individuals to enjoy the right to health, it diminished the enjoyment of some features of the right to health for others.

Against this background, we now consider the efficacy of temporal accountability in relation to the case study explored above. The Constitutional Court’s ruling demonstrates both strengths and weaknesses in temporal accountability—the requirement that government decisions be made within reasonable time frames and that accountability mechanisms operate with appropriate timing.

Strengths in temporal accountability

The court’s decision enhanced temporal accountability in two ways. First, by establishing a clear deadline for legislative action (two years from the judgment date), the court created a specific time frame for democratic deliberation and decision-making. This temporal constraint prevented indefinite delay and forced institutional actors to confront the policy question within a defined period.

Second, by shifting health care financing decisions from administrative discretion to legislative authority, the court established a framework whereby significant policy changes must undergo timely democratic processes rather than emerging through gradual administrative drift.

Weaknesses in temporal accountability

However, the case also reveals temporal accountability shortfalls. Most significantly, the suspend-and-resume scheme operated for years without legislative authorization, demonstrating a prolonged period in which executive action proceeded without proper democratic oversight. The Constitutional Court addressed this issue only after substantial time had elapsed and the scheme had become entrenched in practice.

The two-year deadline set by the court, while creating temporal pressure, also introduced ambiguity. When neither the executive nor legislature acted within this time frame, the NHIA unilaterally terminated the scheme. This outcome raises the question whether temporal accountability was truly achieved, for the scheme ended not through democratic deliberation within the prescribed time frame but through administrative inaction and strategic timing.

Furthermore, the documented pattern of returning expatriates increasingly using the suspend-and-resume scheme for elective procedures suggests that temporal accountability failed to address emerging equity concerns promptly.[41] The system allowed exploitation to grow over time before institutional actors responded.

Assessment of temporal accountability

Overall, this case study demonstrates a mixed record for temporal accountability. While the Constitutional Court established that important health decisions must undergo legislative deliberation, the case itself emerged as a result of years of inadequate temporal accountability in the executive branch. The NHIA’s ultimate decision to terminate the scheme at the deadline, rather than proposing legislation, suggests that temporal constraints can be strategically manipulated to achieve particular outcomes outside the democratic process envisioned by the court.

While terminating the scheme affirms the principle of solidarity through equitable contribution requirements, it is important to acknowledge that this change has created new financial burdens for certain groups. Students studying abroad, diplomatic personnel, and other citizens serving officially overseas now face additional costs that they did not bear under the previous system. When the scheme ended in December 2024, contributing to the NHI system became mandatory for all—no alternative exists.

The Constitutional Court correctly held that health policy decisions should be made through legislation given their public importance. However, it could have further promoted a rights-based approach by referencing international human rights frameworks, which emphasize the right to health, including social determinants and robust health systems. Effective health systems are central to realizing health equity and highlight the need for continual improvement of the NHI system.

The Constitutional Court’s analysis of equal protection and nondiscrimination is key to understanding health equity in Taiwan’s legal system. These obligations help define health equity in practice. Although scholars and the court have not deeply addressed health equity within the NHI system, this paper explores how equity principles support the right to health by promoting fair health care access and resource distribution for all citizens, regardless of socioeconomic status or location.

While various definitions of health equity exist in the literature, the concept can be generally understood as the fair distribution of health without creating unnecessary, avoidable, and unfair health inequities.[42] Since the NHI system aims to promote equality of opportunities, exempting overseas residents from health premium payments may introduce financial uncertainty to the system and result in a situation where overseas residents are treated preferentially over local residents without sufficient justification.

In this context, it is important to note that Taiwan’s National Human Rights Commission, established in 2020, has the authority to investigate human rights violations, review government policies, and recommend reforms. Although not involved with the suspend-and-resume scheme, the commission could assess whether NHI coverage policies infringe on health rights—especially since citizens in Taiwan cannot legally challenge the scheme—and suggest policy changes. This would help address the accountability deficit.

Continuous adjustments prompted by changing social circumstances can yield more responsive outcomes. However, temporal accountability is not a panacea—its effectiveness depends on the quality and inclusivity of institutional interactions. We should not assume that temporal accountability necessarily achieves better outcomes than other approaches to accountability. In particular, risks of majoritarianism persist. When health care governance favors technocratic decision-making, procedural safeguards are necessary to uphold accountability and democratic legitimacy. These should include (1) a public comment period long enough for meaningful stakeholder input, especially from marginalized groups; (2) mandatory disclosure of impact assessments showing how policies affect various populations; and (3) legislative hearings to review outcomes, compare projections with actual results, and adjust policies accordingly. Such measures help balance expertise with democracy and safeguard public trust in health governance.

Scope and limitations of the framework

This case study demonstrates how temporal accountability functions in health systems under specific conditions: constitutional review with authority to set binding timelines, transparent administrative health data, universal coverage with residency-based eligibility rules, and democratic governance with constitutional courts that have limited enforcement power relative to other branches of the government. The insights from this case study may not transfer directly to common-law jurisdictions, where constitutional structures, judicial review, and the relationship between legislative and administrative authority operate under fundamentally different legal principles. To bridge these contexts, Figure 1 outlines five principles of temporal accountability for assessing institutional interactions in health care decisions.

Conclusion

Accountability is a crucial and complex feature of health rights. Our case study on Taiwan reveals how multi-layered accountability helps a national health insurance system adapt continuously to evolving societal needs through checks and balances among co-equal branches of government. We have demonstrated that temporal accountability, despite its shortcomings, offers a valuable lens for understanding rights-based approaches to health systems by emphasizing iterative improvements, time-bound commitments, and institutional oversight.

Temporal accountability in health care governance extends far beyond political responsibility. As the case study demonstrates, a comprehensive view encompasses temporal and human rights dimensions, fostering iterative improvements and transparency in decision-making that clarifies trade-offs between competing values and interests. This expanded conceptualization of accountability enables better understanding of the institutional interactions involved in monitoring, evaluation, and continuous policy adjustments that respond to changing societal needs while maintaining the sustainability and equity of universal health coverage.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Hunt, Anuj Kapilashrami, and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, and Carmel Williams and Morgan Stoffregen for their exceptional editorial support.

Tsung-Ling Lee, SJD, is a professor of law at the Graduate Institute of Health and Biotechnology Law, Taipei Medical University, Taiwan.

Chien-Liang Lee, Dr. iur. is a director and distinguished research professor at Institutum Iurisprudentiae, Academia Sinica, and a professor of law at National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Please address correspondence to Tsung-Ling Lee. Email: tl265@georgetown.edu.tw.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2025 Lee and Lee. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

[1] L. P. Freedman, “Achieving the MDGs: Health Systems as Core Social Institutions,” Development 48/1 (2005).

[2] D. H. Rached, “The Concept(s) of Accountability: Form in Search of Substance,” Leiden Journal of International Law 29/2 (2016).

[3] C. Williams and P. Hunt, “Neglecting Human Rights: Accountability, Data and Sustainable Development Goal 3,” International Journal of Human Rights 21/8 (2017).

[4] N. Daniels, Just Health: Meeting Health Needs Fairly (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

[5] United Kingdom Department for International Development, “Justice and Accountability,” DFID Practice Paper (2008), https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/+/http:/www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications/briefing-justice-accountability.pdf.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] G. Belloni, S. Monod, C. Poroes C, et al., “Health Systems Governance, Shocks and Resilience: A Scoping Review of Key Concepts and Theories,” BMJ Global Health 10 (2024).

[9] J. A. Kiendrébéogo, M. De Allegri, and B. Meessen, “Policy Learning and Universal Health Coverage in Low- and Middle-Income Countries,” Health Research Policy and Systems 18 (2020).

[10] A. Kapilashrami, N. Quinn, and A. Das, Advancing Health Rights and Tackling Inequalities: Interrogating Community Development and Participatory Praxis (Policy Press, 2025).

[11] Human Rights Council, Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health: Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health, UN Doc. A/63/263 (2008).

[12] Human Rights Council, Implementation of General Assembly Resolution 60/251 of 15 March 2006 Entitled “Human Rights Council”: Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health, Paul Hunt, UN Doc. A/HRC/4/28 (2007).

[13] Ibid., para. 46.

[14] L. P. Freedman, “Human Rights, Constructive Accountability and Maternal Mortality in the Dominican Republic: A Commentary,” International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 82/1 (2003).

[15] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000).

[16] L. O. Gostin and Eric A Friedman, “The Health and Human Rights Impact Assessment: The Preeminent Value of Equity,” Health and Human Rights 26/1 (2024).

[17] L. Forman, “‘Rights’ and Wrongs: What Utility for the Right to Health in Reforming Trade Rules on Medicines?,” Health and Human Rights 10/2 (2008).

[18] For various understanding on accountability, see P. Mikuli and G. Kuca (eds), Accountability and the Law: Rights, Authority and Transparency of Public Power, 1st edition (Routledge, 2021).

[19] Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Human Rights Indicators: A Guide to Measurement and Implementation (2012).

[20] P.-C. Lee, J. T.-H. Wang, T.-Y. Chen, and C.-H. Peng, Digital Health Care in Taiwan: Innovations of National Health Insurance (Springer Nature, 2022).

[21] Ibid.

[22] F. Tsai, B. Chen, H. Yang, and S. Huang, Sustainability and Resilience in the Taiwanese Health System (Center for Asia-Pacific Resilience and Innovation, 2024).

[23] T.-L. Lee and Y.-L. Lee, “Maintaining the Right to Health: A Democratic Process in Taiwan,” Health and Human Rights 27/1 (2025).

[24] W. Soon, “Health Insurance, Medicine, and Society in Taiwan: Chinese Authoritarianism, Taiwanese Ethnicities, and Global Actuarial Science,” East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal 389/18 (2024)

[25] World Bank, World Development Report: Investing in Health (1993); World Health Organization, Report of the WHO Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, A55/5 (2002).

[26] S. H.-T. Tsuei, “Reflection on 30 Years of Taiwanese National Health Insurance: Analysis of Taiwanese Health System Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities,” Journal of the Formosan Medical Association 123 (2024).

[27] R. B. Leflar, “Trust, Democracy, and Hygiene Theatre: Taiwan’s Evasion of the Pandemic,” Asian Journal of Law and Society 46/10 (2023).

[28] E. Dean-Richards, “The Successes and Limits of ‘Taiwan Can Help’ Health Diplomacy,” Domino Theory (March 8, 2024), https://dominotheory.com/the-successes-and-limits-of-taiwan-can-help-health-diplomacy/.

[29] Y. T. Yang, “Expats Must Pay Fair Share for Healthcare,” Taipei Times (December 1, 2024), https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2024/12/01/2003827758.

[30] Y. T. Yang, “Reforming Taiwan’s National Health Insurance: From Exploitation to Equitable Participation,” Global Taiwan Institute (January 22, 2025), https://globaltaiwan.org/2025/01/reforming-taiwans-national-health-insurance-from-exploitation-to-equitable-participation/.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] J.-J. Ho and C.-H. Lee, “Suspension and Resumption of Coverage in Taiwan’s National Health Insurance: A Critical Review from Legal and Policy Perspectives,” Taiwan Insurance Review 33/4 (2017).

[34] Constitutional Court R.O.C. Taiwan, “Summary of TCC Judgment 111-Hsien-Pan-19 (2022) [Case on the Suspension and Resumption of the Coverage of National Health Insurance],” https://cons.judicial.gov.tw/en/docdata.aspx?fid=5535&id=346960.

[35] National Health Insurance Administration dataset, https://www.nhi.gov.tw/ch/cp-6015-0907b-3023-1.html (noting that the data are partial).

[36] Constitutional Court (see note 34).

[37] International Conference on Primary Health Care, Declaration of Alma-Ata (1978).

[38] 院總第 20 號 委員 提案第 11006937 號

[39] National Health Insurance Act, amended on June 28, 2023.

[40] Lee and Lee (see note 23).

[41] T. Hsi-Hua, S. Yu-Lian, and H. Shu-Ying, “Who Created the ‘Huang Ans’? Two Backdoor Clauses Turn the National Health Insurance Act into a Political Sacrifice,” The Reporter, https://www.twreporter.org/a/opinion-covid-19-national-health-insurance-act-dispute.

[42] M. Whitehead, “The Concepts and Principles of Equity and Health,” International Journal of Health Services 22/3 (1992).