Human Rights Accountability in Global Health Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships: The Case of the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator

EXPLORING ACCOUNTABILITY FOR HEALTH RIGHTS Vol 27/2, 2025, pp. 65-77 PDF

Gamze Erdem Türkelli and Rossella De Falco

Abstract

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development promotes multi-stakeholder partnerships (MSPs) to achieve sustainable development, including global health-related goals. MSPs typically involve three or more types of actors, including states, corporations, philanthropic organizations, civil society, and multilateral institutions. While MSPs often operate in sectors that are crucial for the realization of health-related rights, they are seldom analyzed through a human rights lens. This paper will advance knowledge in this field through an exploration of the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A), launched in 2020. In doing so, the paper sheds light on the direct accountability of MSPs to rights holders, as well as the state obligations to respect and protect human rights in the context of MSPs. The paper outlines a human rights accountability framework to investigate the ACT-A’s accountability structure. The analysis confirms three systemic accountability problems: diffused responsibility in terms of the applicable normative and legal frameworks; limited answerability to rights holders; and weak enforceability in terms of remedies. This, in turn, limits the possibility of health rights accountability, including review, monitoring, and remedial action. The conclusions highlight three solutions: that MSPs themselves should at least have the duty to respect human rights, as do other corporate entities; that an independent, people-centered mechanism to hold MSPs accountable should be established; and that multilateral governance solutions, including seats at the table for less powerful actors, should be prioritized over multi-stakeholder approaches.

Introduction

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development promotes multi-stakeholder partnerships (MSPs) as a tool to finance and deliver sustainable development. The Sustainable Development Goals feature goal 17 on strengthening global partnership for development, with targets 17.16 and 17.17 focused on MSPs. Today, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund) and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance are among the largest global health MSPs.

Scholars refer to such agreements using different terms, including “international health initiatives” or “global health partnerships.”[1] In this paper, we rely on Barbara Gray and Jill Purdy’s definition of MSPs as cooperative partnerships involving three or more types of actors, such as states, corporations, nonprofit organizations, academic actors, civil society, philanthropic actors, or multilateral institutions (such as the World Health Organization or the World Bank).[2]

Because MSPs include a broader range of actors and operate under flexible, often context-specific agreements, they are fundamentally different from public-private partnerships, which normally entail a long-term contract between a state and a private health care actor.[3]

Concerningly, MSPs have been gaining center stage in global development policymaking without due regard to human rights accountability.[4] For instance, while the actors that participate in MSPs manage substantial financial resources that could impact the lives of many, their obligations under international human rights law, as well as their development cooperation commitments, are still unclear.

This paper seeks to address this gap through the case study of the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A), a global collaboration launched in April 2020 and aimed at accelerating the development, production, and equitable distribution of COVID-19 tests, treatments, and vaccines at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The paper first introduces a normative and operational framework to analyze human rights accountability in global health MSPs. The second section details states’ obligations to respect, protect, and fulfill health-related rights within and beyond their jurisdictions, as well as the direct human rights responsibilities of companies and international organizations. In the third section, the paper applies the human rights accountability framework introduced in the first section to the case study of the ACT-A, using its governance structure as a springboard for discussion.

Given that MSPs have emerged from the 1990s onwards as global governance tools in response to global discussions around the financing and achievement of sustainable development, we build on earlier and broader work by Erdem Türkelli on the accountability of MSPs as development financing actors, which inspects the problems of diffused responsibility, limited answerability, and weak enforceability in transnational MSPs. We use a hybrid lens by then connecting these known limitations to health rights accountability, including review, monitoring, and remedial action.[5] The paper thus seeks to analyze whether and to what extent human rights accountability existed in the context of the ACT-A’s multi-stakeholder partnership model while it was operational.

Methodologically, this reflection uses case study analysis to draw conclusions that may be helpful for understanding the larger accountability challenges posed by MSPs in global health. It relies on desk research and document analysis of publicly available academic and gray literature related to the ACT-A over 2020–2025.

The conclusions critically examine the implications for the people-centered sphere of health rights accountability, suggesting potential solutions and highlighting future research agendas.

Navigating accountability in health MSPs: Developing a framework

Beyond state-centric forms of accountability, social movements, civil society, and human rights defenders have developed their own strategies to hold governments accountable, including in global health. For instance, in describing a process of “global health governance from below,” Lisa Forman highlights the pivotal role played by AIDS activists in reframing access to essential medicines as a human right through campaigning, advocacy, mobilization, and strategic litigation, leading to major wins.[8]

Matthew Canfield and Sara Davis, instead, reflect on people-led forms of accountability in institutionalized spaces, such as MSPs.[9] While conceding that there are several human rights concerns associated with MSPs, the authors argue that human rights activists may be developing new ways to exercise “moral power” in these new global health partnerships, including through formal representation, oral statements, and internal lobbying.[10]

From a sustainable development and human rights perspective, we rely on three components of accountability: responsibility, answerability, and enforceability.[11] Responsibility denotes the existence of “clearly defined duties and performance standards” for those involved in decision-making roles; answerability requires to “provide reasoned justifications” to affected individuals and communities; and enforceability includes prevention and correction when necessary.[12] This framework can be easily adapted to the field of cooperation and development aid, and it is well-suited for normative analysis at a systems level across different human rights.[13]

This theoretical framework is further complemented by a tripartite conceptualization of health rights accountability: monitoring, review, and remedial action.[14] Monitoring means providing critical and reliable information on results and resources, including through the collection of quality and disaggregated data. Review means assessing “whether pledges, promises and commitments have been kept by countries, donors and non-state actors”—for example, has the health of populations progressively improved? Finally, remedial action involves remedies, reparations, and redress.[15] For the purpose of this paper, we conceptualize accountability for the right to health as combining the metrics of responsibility, answerability, enforceability, monitoring, review, and remedy at an operational level.[16]

The growing role of MSPs in global health

The health sector features some of the earliest examples of transnational partnerships. In 1974, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the Onchocerciasis Control Programme in partnership with the World Bank and the United Nations Development Programme to control onchocerciasis in Western Africa. Later examples include the Medicines for Malaria Venture, launched in 1999, set up as a collaboration between a range of institutional, public, and private stakeholders, including WHO, the World Bank, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the US government.[17]

Transnational MSPs experienced a surge in all global governance domains starting with environmental governance after their incorporation into the global sustainable development agenda through the idea of a global partnership for sustainable development (Agenda 21 of the 1992 Rio de Janeiro Conference and later Millennium Development Goal 8). The 2002 Johannesburg Summit embraced so-called Type II outcomes (voluntary actions running alongside negotiated intergovernmental outcomes), further enabling multi-stakeholder approaches to various sustainable development domains. In the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, goal 3 focuses on health, while goal 17 seeks to “strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development.”

Beyond environmental governance, multi-stakeholderism started permeating global health widely through partnerships such as the Global Fund and Gavi. Alongside these, new private-led development financing tools also rapidly expanded, such as the International Finance Facility for Immunisation, advance market commitments for vaccines, the Affordable Medicines Facility-malaria, and the Global Fund’s Debt2Health swaps.[18] Some philanthropic actors that were key in establishing global health partnerships, like the Gates Foundation, have also become influential, thanks to their diplomatic network, in global norm-making responses to infectious diseases, including in epidemic and pandemic settings.[19]

The expansion of multi-stakeholder solutions to global health problems is based largely on promises of flexibility and agility. For instance, proponents of MSPs argue that they provide a rapid response to health challenges by bringing together interested partners that are willing to collectively act, including through mobilizing both public and private funds. Based on this promise, the multi-stakeholder partnership model has become the “go-to” template when faced with new health challenges.

Despite their promises, when MSPs are employed as the first line of intervention in tackling global challenges, public accountability may be compromised.[20] For instance, in vaccine development, a recent scoping review finds weak legitimacy, transparency, and accountability mechanisms across multiple MSPs.[21] A range of studies find that MSPs may also dilute accountability, promote the interests of private actors, create power imbalances, and overfocus on disease-specific interventions rather than health systems strengthening.[22] Furthermore, they also often facilitate the involvement of private actors in domestic health care systems, which some observers find problematic.[23]

Given that there is currently no clear human rights law framework governing MSPs as human rights duty bearers, in the following section we outline the human rights framework that applies to the constitutive parts of global health MSPs, especially during public health emergencies: states, international organizations, and nonstate actors, particularly business enterprises and philanthropic actors.

The applicable legal framework

Tripartite obligations for right to health and public health emergencies

States’ human rights obligations are tripartite: respect, protect, and fulfill. For instance, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights specifies that states must respect the right to health by refraining from limiting access to health care services or imposing discriminatory practices.[24] Furthermore, states must protect the right to health by ensuring, inter alia, equal access to health care provided by third parties or by controlling the marketing of medical goods by third parties.[25] The obligation to fulfill refers to a wide range of measures, such as the adoption of a national health plan.[26]

In the context of public health emergencies, states must ensure that human rights are protected both by respecting them and by taking positive steps.[27] In particular, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) obligates states to progressively realize the right to health, including by taking steps necessary for “the prevention, treatment, and control of epidemic, endemic, occupational and other diseases.”[28] Health rights accountability includes effective judicial and other remedies at both national and international levels for those who have suffered violations.[29]

The ICESCR also protects the right to benefit from scientific progress and its applications (the right to science).[30] While access to vaccines and other medical goods is deeply compromised by global inequalities, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has reaffirmed that the intellectual property regime should be interpreted and implemented as reinforcing states’ duty “to protect public health and, in particular, to promote access to medicines for all.” [31]

Human rights beyond borders: Extraterritorial obligations

So-called extraterritorial human rights obligations bind states to abide by their human rights obligations beyond their borders.[32] In the context of health, extraterritorial human rights obligations are grounded in article 2(1) of the ICESCR, which imposes a legal duty on states to realize economic, social, and cultural rights through, inter alia, international assistance and cooperation.

States also retain their full range of human rights obligations as members of international organizations, as reiterated by both the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Committee on the Rights of the Child in their various general comments, including those on the right to health.[33]

The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights additionally note that member states of international organizations should “ensure that those institutions neither restrain the ability of their member States to meet their duty to protect nor hinder business enterprises from respecting human rights” and “encourage [international organizations] … to promote business respect for human rights and, where requested, to help States meet their duty to protect against human rights abuse by business enterprises, including through technical assistance, capacity-building and awareness-raising.”[34]

Human rights beyond the state

International organizations

Beyond the human rights duties of the member states of international organizations, many scholars have argued that international organizations themselves are or ought to be direct human rights duty bearers.[35] This position is also espoused in the Maastricht Principles.[36] Duties of international organizations under international human rights law are linked to their mandates as conferred to them by state parties and enumerated in their foundational documents, as well as human rights treaties. For instance, article 22 of the ICESCR points to harnessing the expertise of United Nations organs, subsidiary organs, and specialized agencies to “contribute to the progressive implementation” of the covenant. Article 24 of the ICESCR notes the “respective responsibilities” of various United Nations organs and specialized agencies with respect to economic, social, and cultural rights. The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights highlights that international organizations should “cooperate effectively with states parties, building on their respective expertise, in relation to the implementation of the right to health at the national level, with due respect for their individual mandates,” calling on the World Bank and International Monetary Fund to pay special attention to the right to health in their activities.[37]

Central for this discussion is the role of WHO, which is the sole United Nations health agency. The WHO Constitution lists one objective for the entire organization—“attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of health” (art. 1)—and mentions the right to health in its preamble. WHO’s functions include, inter alia, directing and coordinating international health work, assisting states, and coordinating lawmaking and standards in the context of global health. The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights further notes that WHO plays a critical role in the realization of the right to health, particularly given its technical know-how and capabilities.[38] While the WHO Constitution describes the institution’s role in addressing infectious disease as “to stimulate and advance work to eradicate epidemic, endemic and other diseases” (art. 2(g)), the preamble refers to the potential adverse impacts of “unequal development” on the “promotion of health and control of disease, especially communicable disease.”

Private actors: Businesses and charitable foundations

The human rights responsibilities of businesses and philanthropic actors, often legally assuming the form of charitable foundations, are domains in which human rights law has been in constant evolution over the last decades. With the Human Rights Council’s endorsement of the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, as well as the ongoing drafting of a legally binding instrument on business and human rights, there is growing consensus that corporations hold certain human rights duties, albeit with a more limited scope than states.[39]

The Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights introduce a three-pillar framework (protect, respect, and remedy): states have the primary obligation to protect human rights from interference by third parties (including business enterprises); businesses have a responsibility to respect human rights by, inter alia, not causing harm or contributing to adverse human rights impact; and remedy ought to be provided in case of adverse human rights impacts caused by or contributed to by businesses. The baseline duty of businesses to respect is to be carried out through human rights due diligence as a mechanism to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for possible human rights violations.[40]

The human rights community has also paid attention to the human rights responsibilities of private actors when they provide essential services, such as in the context of health care. As noted by Paul Hunt, former Special Rapporteur on the right to health, pharmaceutical companies should ensure transparency, price and licensing flexibility, and access to information, and they should be accountable to the public.[41] The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has also emphasized that “business entities, including pharmaceutical companies, have the obligation, as a minimum, to respect Covenant rights” and that states should “refrain from invoking intellectual property rights in a manner that is inconsistent with the right of every person to access a safe and effective vaccine for COVID-19.”[42]

Further, the committee has rightly noted that “private providers [of public services] should … be subject to strict regulations that impose on them so-called ‘public service obligations.’”[43]

Nonetheless, the question of accountability around the actions of charitable foundations, particularly very strong and influential ones, such as the Gates Foundation or the Wellcome Trust, has not been subject to much contemplation in legal scholarship. At the same time, while philanthropic organizations lack accountability to the public, they wield arbitrary power, often shape decision-making and discourse, and wield their influence and power consciously through network diplomacy.[44] Thus, human rights responsibilities of charitable foundations or other philanthropic actors should at least mirror those of business enterprises and cover the baseline obligation to respect human rights in all circumstances as well as be analogous to those of private providers in cases where these actors provide public services.

A case study: Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator

Launched in April 2020, the ACT-A was framed as a global “collaboration to accelerate development, production, and equitable access to COVID-19 tests, treatments, and vaccines.”[45] The ACT-A rapidly brought together private foundations, international organizations, and other multi-stakeholder initiatives, including Gavi and the Global Fund.[46] The ACT-A comprised three pillars, respectively dedicated to vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics, and one transversal Health Systems and Response Connector. Governments and the Gates Foundation were part of the ACT-A Facilitation Council, formally launched during a virtual meeting of its members on September 10, 2020.[47]

Katerini Storeng and others describe the resulting institutional arrangement as an experimental “super-[public-private partnership], which resembles a series of Russian Matryoshka dolls of decreasing size nested into each other.”[48] The authors further argue that this institutional complexity has led to unclear accountability mechanisms and blurs the boundaries between public and private spheres.[49]

Suerie Moon and others also note that “the mix of public and private authority within a multistakeholder initiative raises challenges for ensuring accountability in the public interest.”[50] The authors do not find an ACT-A-wide accountability mechanism; rather, each participating organization was accountable to its own governing body.[51] The authors further noted that it remained unclear whether and how governments could exercise authority within the ACT-A, also given the role of WHO as host and technical advisor.[52]

Jelena von Achenbach contends that the vaccine pillar of the ACT-A, COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX), fell short of accountability mechanisms.[53] Achenbach contends that there was no way of holding Gavi, the legal administrator of COVAX, accountable on specified targets, and that this is consistent with COVAX being based on “freedom of contract under private law and the voluntary nature of state action.”[54]

During its early phase, the ACT-A action was reviewed and evaluated largely internally, including the interim ACT-Accelerator Strategic Review conducted in October 2021.[55] The review noted problems related to a lack of accountability but considered it as a trade-off for rapid responsiveness. Subsequently, an external evaluation of the ACT-A was commissioned in 2022, through the initiative of the Facilitation Council (by then-co-chairs South Africa and Norway), to identify lessons learned for future pandemics.[56] The review found that most delivery targets were not met, except for the vaccine pillar, which, although falling short of its objectives, still managed to deliver nearly two billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines globally.[57] Despite its relevance in the rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic when it was most needed, the partnership’s informal coordination model was deemed insufficient, the coordination across the different pillars of diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines too weak, and the financing gap between needs and resource mobilization too large.[58]

Overall, the ACT-A’s COVAX had ambitious aims but was unable to deliver its objective to shape markets and make vaccines available at better rates for developing countries. Developing countries (those classified as either low income or lower-middle income) were not included in the governance and did not feel ownership. According to the evaluation, the ACT-A was seen as “sacrific[ing] inclusion for an assumed decisive and rapid response.”[59]

The partnership remained global but did not effectively engage with regional platforms, undercutting its eventual results and its potential to assist in developing local capabilities.[60] The operating model of the partnership was reckoned as having “limited cross-pillar and within-pillar coordination, insufficient accountability,” a lack of integration with beneficiary country health systems, and “an insufficient focus on delivery.”[61]

With respect to accountability, the key concerns identified by surveyed stakeholders were threefold: the accountability system was decentralized and delegated to individual agencies and pillars; decision-making, resource allocation, and reporting were not fully transparent; and the structure was top-down and informal but also complex.[62] Even if some constitutive institutions of the ACT-A had inclusive and strong management systems, they could not exercise effective oversight over this ad hoc partnership. Some respondents even lamented the lack of a “structure to enable collective accountability” at the MSP level, while insufficient accountability and transparency allowed corporate partners and donors to have an outsized influence.[63]

Even in the pillars of the ACT-A that were considered a success by the evaluation, particularly the vaccine arm and COVAX Advance Market Commitments, performance was not fully satisfactory. The pillar on therapeutics did not achieve its delivery targets for treatment drugs, but oxygen delivery was considered improved. The diagnostic pillar was seen to make “substantial upstream contributions” but was “hampered by an insufficient focus on delivery and by late WHO guidance for self-tests.”[64]

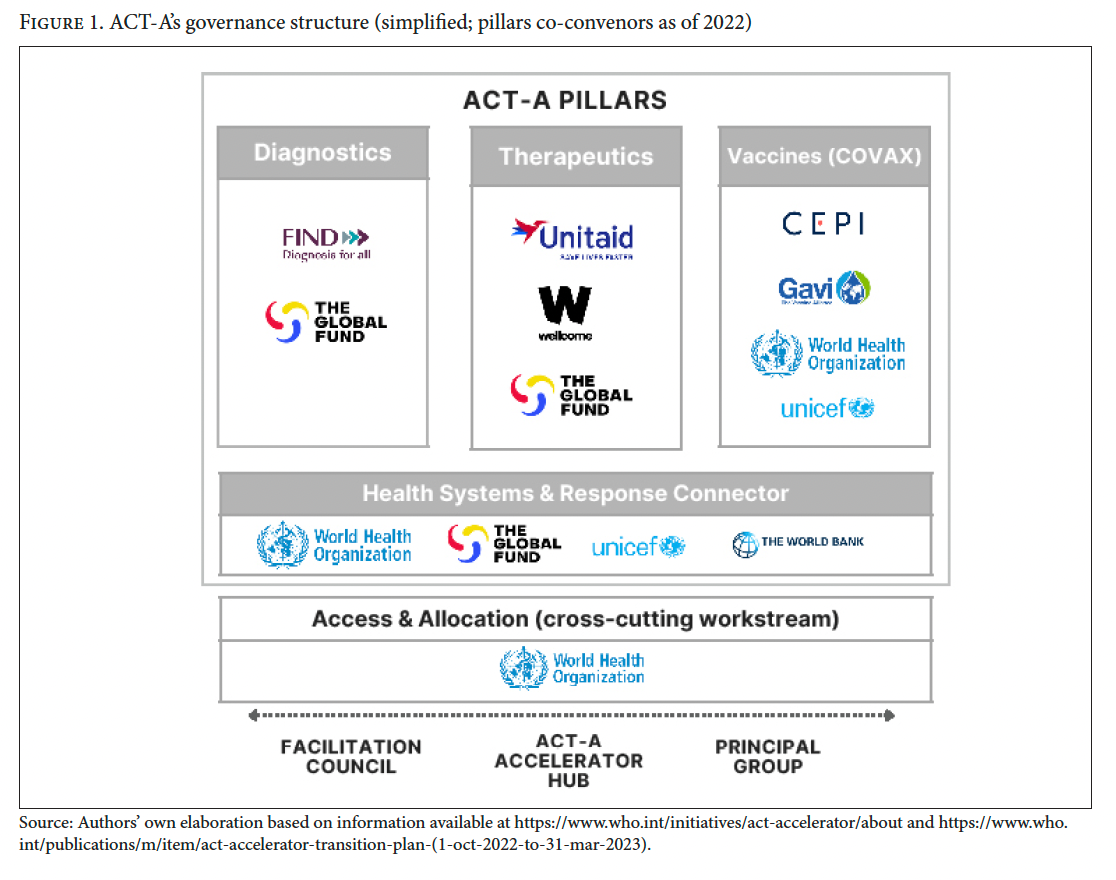

Consistent with literature on the topic, we underline that the ACT-A relied on an amalgamating action through previously established health initiatives, ranging from research to the development of new vaccines (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 illustrates several different types of co-conveners of the four pillars, in addition to states that were involved as donors or recipients of international cooperation:

- International organizations: WHO and the World Bank

- Existing global health MSPs: the Global Fund (focusing on HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis), Gavi (focusing on vaccines), and Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (focusing on creating new vaccines for emerging infectious diseases)

- Charitable foundations: Wellcome Trust, Unitaid, and FIND.

Finally, as seen in the ACT-A setup, international organizations often act as liaisons between the multilateral system and MSPs. WHO can both coordinate with the United Nations, special agencies, governments, scientific and professional organizations, and “such other organizations as may be deemed appropriate” (as per its Constitution, art. 2(b)), and consult and cooperate with international nongovernmental organizations (art. 70). Additionally, the World Bank can act as a link from an MSP to health systems and health policy at the national level or provide trusteeship for the funds pooled within an MSP. The World Bank can be a trustee of such funds under the rubric of either trust funds or financial intermediary funds.[65]

Human rights accountability in the ACT-A: Analysis and findings

In this section, we apply the working framework of accountability outlined earlier to the case study of the ACT-A.

Multi-stakeholder approaches to responding to health emergencies often aim at providing rapid responses and effective collaboration between a range of public and private actors. This is the broader structural and systemic context in which MSPs are created to tackle health emergencies caused by infectious diseases. Within this context, health MSPs may be centralized or decentralized, and they may or may not include mechanisms for transparency and accountability. For this reason, we analyze health and human rights accountability in multi-stakeholder responses to pandemics at two levels: (1) the structural and systemic level and (2) the intervention and partnership (ACT-A) level.

Responsibility (clearly defined duties and performance standards) as a component of accountability

The ACT-A exposed a lack of clearly defined duties and performance standards for public and private actors involved in pandemic preparedness and response.

From the viewpoint of international human rights law, donor states—both individually and as members of WHO and the World Bank—were bound by their right to health and international cooperation obligations. Yet beyond a broad international cooperation obligation under human rights law, the differentiated situation of developing versus wealthy countries did not guide the actions of wealthy countries in allocating resources in ways that prioritized the most vulnerable. As Antoine de Bengy Puyvallée and Katerini Storeng point out in relation to COVAX, “boards of the respective participating institutions formally [bore] the ultimate responsibility for the organizations’ actions, but ha[d] no mandate for the overall COVAX initiative and these boards [we]re dominated by donor governments and the pharmaceutical industry.”[66] The multitude of actors—both public and private—also obfuscated who owed international cooperation duties, as well as duties in relation to sharing the benefits of scientific progress. Furthermore, beyond the human rights duties of the ACT-A’s constituent institutions, the human rights duties that applied to the partnership remained unclear given its hybrid setup bringing together a diverse set of public and private actors, as well as its ad hoc and time-bound nature.

Answerability as a component of accountability

There has been a complete lack of rights-holder centricity in multi-stakeholder action in global health, particularly around pandemics. All institutions—including states, which have clear obligations under international law with respect to respecting, protecting, and fulfilling the right to health and international cooperation—have participated in the pandemic response based on charity. The action of nonstate entities has also been guided by the same logic but without the imperatives of human rights law. Notwithstanding the fact that companies participating in the ACT-A, such as the pharmaceutical companies, were operating within their core business and not purely charitably, the ad hoc and voluntaristic nature of the partnership also obscured the baseline duty of these business enterprises to respect human rights, including, in this case, the right to health. As noted by global civil society organizations, such top-down and charity-oriented programming is not in line with a rights-based or people-centered approach.[67] This has led to the ACT-A not being answerable to rights holders who ought to have been the ultimate beneficiaries.

The opportunity cost of investing in time-bound, multi-stakeholder, market-based, or charity-based solutions is also difficult to quantify. Nonetheless, multi-stakeholder solutions may have contributed to deprioritizing structural solutions, such as the proposed waiver to certain provisions of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights in the context of the COVID-19 emergency.[68] Given that patent waivers were the main demand of the People’s Medicine Alliance, a global movement of more than 100 nongovernmental organizations across 33 countries, we note that multi-stakeholder approaches risk further sidelining civil society’s voices.[69]

Enforceability as a component of accountability

There is a lack of enforceability of human rights and other standards, such as in relation to whether MSPs meet the health rights criteria of availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality, which also rings true for the ACT-A. Even as this ad hoc partnership constituted the main coordinated response to the pandemic at the global level, right to health norms were not enforceable in the context of that response. First, the multi-stakeholder approach espoused could not be scrutinized on whether it fostered or hampered availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality. Second, human rights norms and criteria were not enforced against decisions and actions in the context of the ACT-A once it was set up and operational.

Monitoring, review, and remedial action as components of accountability

The monitoring, review, and remedy framework, when applied to the ACT-A, sheds light on various shortcomings linked to this ad hoc partnership.

With respect to monitoring, some data tracking facilities were created, including the COVID-19 Access Tracker, the ACT-Accelerator Commitment Tracker, and the UNICEF COVID-19 Market Dashboard, but there was criticism about the top-down, uncoordinated, and ad hoc establishment of such data trackers.[70]

With respect to review, there were shortcomings from the beginning, owing to the lack of inclusivity and transparency in decision-making and accountability. Reviewing and assessing the practice of the ACT-A against promises and assurances, as well as against human rights and other standards, seldom took place. While some of the constituent entities such as the Global Fund may have their own mechanisms for auditing and investigating allegations of fraud and abuse, the ACT-A did not have a mechanism of its own. Civil society and community representatives to the ACT-A sent a letter early in February 2021 to leaders of institutions participating in the ACT-A to, inter alia, raise concerns about the lack of transparency in decision-making and the lack of input from civil society representing the interests of rights holders. The letter also noted poignantly that beneficiary countries were not consulted, and some were “learning about their COVAX allocations from press announcements rather than through formal communications from the COVAX Facility itself.”[71]

With respect to remedy, the ACT-A, as an entity, did not establish any redress or remediation mechanisms. It is unclear whether existing accountability mechanisms under the auspices of the ACT-A partners could be deployed for redress and remedy of claims related to the ACT-A.

Conclusion

Our empirical human rights analysis of the ACT-A confirms its accountability challenges, including diffused responsibility due to a lack of clarity about the rules and norms that apply to various types of public and private partners and the division of duties between these partners. In addition, answerability to beneficiaries is often limited, while the interests and priorities of powerful partners, who often promote private interests and corporate models, prevail. Finally, when rights holders seek to enforce the commitments that have been made voluntarily by MSPs, they encounter weak or nonexistent enforceability mechanisms. This in turn also influences the ACT-A showing weak monitoring, inconsistent review, and largely absent remedial mechanisms. While additional comparative research is needed to generalize our findings related to the ACT-A to other health MSPs, this paper reinforces the evidence provided by previous scholarship on the topic.[72]

These shortcomings are problematic in the context of future pandemic governance, which is likely to continue building on disease-specific, multi-stakeholder approaches. For instance, in September 2022, the Financial Intermediary Fund for Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response (Pandemic Fund), hosted by the World Bank, was established, and concerns about it are already being raised.[73] By the same token, the WHO Pandemic Agreement introduced the Global Supply Chain and Logistics Network, which would be “developed, coordinated and convened” by WHO in partnership with “relevant stakeholders” to enhance and facilitate “access to pandemic-related health products for countries in need.”[74]

However, like the ACT-A experience, future multi-stakeholder approaches may prioritize private interests while sidelining rights holders as well as developing countries’ priorities, especially in a broader context in which global health law developments are not being fully foregrounded in human rights law.[75] To tackle future health emergencies, strengthening existing multilateral global health systems allows the global community to provide a structural response. By contrast, ad hoc, amalgamated multi-stakeholder initiatives, which appear only to disappear or become obsolete, risk further fragmenting global health policy and diverting resources away from the public sector.

Based on our findings, and the future prominence of multi-stakeholder responses to global health emergencies, we need to rethink how to tackle accountability deficits of multi-stakeholder approaches to global health problems. Multi-stakeholder solutions often overlook less powerful actors, such as states (especially developing countries) and human rights holders. This is because philanthropic foundations and existing powerful MSPs tend to divert public financing to charity and market-based approaches with the promise of rapid response and agility, which often do not materialize, to the detriment of rights holders. In other words, we need to rethink how global health policymaking can effectively be devised without the intermediation of powerful private actors.

We propose three potential solutions. First, from a legal standpoint, we argue that—at a minimum— the baseline duty contained in the business and human rights frameworks of respecting human rights in all activities, decisions, and relationships should apply to philanthropic actors and charitable foundations as well as MSPs. When any of these actors engage in the provision of public services, they should also similarly be subject to “public service obligations” as outlined by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in General Comment 24.[76]

The committee also highlights that “priority in the provision of international medical aid, distribution and management of resources, such as safe and potable water, food and medical supplies, and financial aid should be given to the most vulnerable or marginalized groups of the population.”[77] Going forward, discussions around public accountability for pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response, whether based on multi-stakeholder approaches or purely public approaches, should ensure that the rights of the most vulnerable and marginalized parts of the global population are respected and their health care needs met.

Second, within existing MSPs, a solution might be to devise an external, independent body that effectively holds them and their constitutive members accountable. This mechanism would include procedural requirements to ensure the effective and meaningful participation of those affected by the development projects that MSPs handle. Such independent review and monitoring bodies may be built into existing multilateral institutions with global membership, such as WHO, UNESCO, the Food and Agriculture Organization, and others, depending on the issue area.

Finally, looking for solutions at the interface of human rights law and governance, multilateral, structural solutions embedded in international cooperation duties and guided by human rights norms should be prioritized over multi-stakeholder approaches. Pivotally, these long-term solutions should envision seats at the table for developing-country representatives as well as public interest civil society groups.

Funding

The research on which this paper is based is funded by the European Union (ERC Starting Grant, GENESIS, 101117107). The views and opinions expressed, however, are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Gamze Erdem Türkelli, PhD, is an associate research professor at the Law and Development Research Group, Faculty of Law, University of Antwerp, Belgium.

Rossella De Falco, PhD, is a postdoctoral researcher at the Law and Development Research Group, Faculty of Law, University of Antwerp, Belgium.

Author contributions

Gamze Erdem Türkelli: conceptualization, data curation, financial acquisition, investigation, methodology, writing – review and editing.

Rossella De Falco: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, project administration, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Please address correspondence to gamze.erdemturkelli@uantwerpen.be

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2025 Erdem Türkelli and De Falco. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

[1] B. Hunter and S. F. Murray, “Deconstructing the Financialization of Healthcare,” Development and Change 50/5 (2019).

[2] B. Gray and J. Purdy, Collaborating for Our Future: Multistakeholder Partnerships for Solving Complex Problems (Oxford University Press, 2018).

[3] G. L. Burci, “Public/Private Partnerships in the Public Health Sector,” International Organizations Law Review 6/2 (2009).

[4] L. B. Andonova, and M. A. Levy, “Franchising Global Governance: Making Sense of the Johannesburg Type II Partnerships,” in S. Stokke and Ø. B. Thommessen (eds), Yearbook of International Cooperation on Environment and Development 2003/2004 (Earthscan Publications, 2003).

[5] G. Erdem Türkelli, “Multistakeholder Partnerships for Development and the Financialization of Development Assistance,” Development and Change 53/1 (2022).

[6] H. Potts, Accountability and the Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health (University of Essex, 2016), p. 13.

[7] Ibid., pp. 13–16.

[8] L. Forman, “Global Health Governance from Below: Access to AIDS Medicines, International Human Rights Law, and Social Movements,” in A. F. Cooper and J. J. Kirton (eds), Innovation in Global Health Governance (Taylor and Francis, 2009).

[9] M. Canfield and S. L. M. Davis, “Multistakeholderism and Human Rights: A Call for an Anthropological Approach,” Journal of Human Rights Practice 17/3 (2025).

[10] Ibid., p. 6.

[11] Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and Center for Economic and Social Rights, Who Will Be Accountable? Human Rights and the Post-2015 Development Agenda (2013).

[12] Ibid., p. 9.

[13] G. Erdem Türkelli, “Transnational Multistakeholder Partnerships as Vessels to Finance Development: Navigating the Accountability Waters,” Global Policy 12/2 (2021).

[14] Commission on Information and Accountability, Keeping Promises, Measuring Results (World Health Organization, 2011).

[15] Ibid.

[16] C. Williams and P. Hunt, “Neglecting Human Rights: Accountability, Data and Sustainable Development Goal 3,” International Journal of Human Rights 21/8 (2017).

[17] T. Sandler, “Financing International Public Goods,” in M. Ferroni and A. Mody (eds), International Public Goods: Incentives, Measurement, and Financing (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002).

[18] Erdem Türkelli (2022), see note 5.

[19] A. de Bengy Puyvallée, K. T. Storeng, and S. Rushton, “The Gates Foundation’s Network Diplomacy in European Donor Countries,” Global Health 21/22 (2025).

[20] G. Erdem Türkelli, Children’s Rights and Business: Governing Obligations and Responsibilities (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

[21] C. Nunes, M. McKee and N. Howard, “The Role of Global Health Partnerships in Vaccine Equity: A Scoping Review,” PLOS Global Public Health 4/2 (2024).

[22] A. Ruckert and R. Labonté, “Public-Private Partnerships in Global Health: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly,” Third World Quarterly 35/9 (2014); F. Stein, “Risky Business: COVAX and the Financialization of Global Vaccine Equity,” Globalization and Health 17/1 (2021); K. T. Storeng, “The GAVI Alliance and the ‘Gates Approach’ to Health System Strengthening,” Global Public Health 9/8 (2014).

[23] J. Hoekstra and L. F. Yanes, “The Mismatch of Public-Private Partnerships and the Right to Health,” in O. Martin-Ortega and L. Treviño-Lozano (eds), Sustainable Public Procurement of Infrastructure and Human Rights (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2023); R. De Falco, T. F. Hodgson, M. McConnell, and A. Kayum Ahmed, “Assessing the Human Rights Framework on Private Health Care Actors and Economic Inequality,” Health and Human Rights 25/2 (2023).

[24] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000), paras. 11, 12.

[25] Ibid., para. 35.

[26] Ibid., paras. 36–37.

[27] United Nations Economic and Social Council, The Siracusa Principles on the Limitation and Derogation Provisions in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, UN Doc. E/CN.4/1985/4 (1984); Global Health Law Consortium and ICJ, Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Public Health Emergencies (2023); L. Forman, “The Evolving International Law Standards Governing Restrictions of Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights During Public Health Emergencies,” Journal of Global Health Law 1/2 (2024).

[28] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI) (1966), art. 12(c).

[29] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 24), para. 59.

[30] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see note 28), art. 15(b).

[31] L. Bottini Filho, S. A. Karim, T. F. Hodgson, “Vaccine Inequity in the COVID-19 Crisis: Lessons to Leverage Global Health Law Through Market-Shaping Policies,” Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 53/S1 (2025); Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 25, UN Doc. E/C.12/GC/25 (2020).

[32] Maastricht Principles on Extraterritorial Obligations of States in the Area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2011); O. De Schutter, A. Eide, and A. Khalfan, “Commentary to the Maastricht Principles on Extraterritorial Obligations of States in the Area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights,” Human Rights Quarterly 34/4 (2012).

[33] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 24); Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 15 (2013), UN Doc. CRC/C/GC/15 (2013).

[34] Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (2011), principle 10.

[35] See S. I. Skogly, The Human Rights Obligations of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (Cavendish Publishing, 2003); W. V. Genugten, P. Hunt, and S. Mathews (eds), World Bank, IMF and Human Rights (Wolf Legal Publishers, 2003).

[36] O. De Schutter, A. Eide, A. Khalfan, et al., “Commentary to the Maastricht Principles on Extraterritorial Obligations of States in the Area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights,” Human Rights Quarterly 34/4 (2012), pp.1084–1169.

[37] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 24), para. 64.

[38] Ibid., para. 63.

[39] Human Rights Council, “Open-Ended Intergovernmental Working Group on Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises with Respect to Human Rights,” https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/hrc/wg-trans-corp/igwg-on-tnc.

[40] For domestic-level examples, see United Kingdom, Modern Slavery Act (2015); France, Loi n° 2017-399 du 27 mars 2017 relative au devoir de vigilance des sociétés mères et des entreprises donneuses d’ordre, JORF n° 0074 du 28 mars 2017, texte n°1; Netherlands, Wet Zorgplicht Kinderarbeid (2019).

[41] United Nations General Assembly, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health, UN Doc. A/63/263 (2008).

[42] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Statement on Universal and Equitable Access to Vaccines for the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19), UN Doc. E/C.12/2020/2 (2020), para. 17.

[43] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 24, UN Doc. E/C.12/GC/24 (2017).

[44] R. Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy and How It Can Do Better (Princeton University Press, 2018); G. D. Blunt, “The Gates Foundation, Global Health and Domination: A Republican Critique of Transnational Philanthropy,” International Affairs 98/6 (2022).

[45] World Health Organization, “ACT-A: About,” https://www.who.int/initiatives/act-accelerator/about.

[46] World Health Organization, Commitment and Call to Action: Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator; A Global Collaboration to Accelerate the Development, Production and Equitable Access to New COVID-19 Diagnostics, Therapeutics and Caccines (2020).

[47] ACT-Accelerator Facilitation Council, “Terms of Reference” https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/act-accelerator-facilitation-council—terms-of-reference-english.pdf?sfvrsn=55190ad7_1.

[48] K. T. Storeng, A. de Bengy Puyvallée, and F. Stein., “COVAX and the Rise of the ‘Super Public Private Partnership’ for Global Health,” Global Public Health 18/1 (2023).

[49] Ibid.

[50] S. Moon, J. Armstrong, B. Hutler, et al., “Governing the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator: Towards Greater Participation, Transparency, and Accountability,” Lancet 399/10323 (2022).

[51] Ibid.

[52] Ibid.

[53] J. von Achenbach, “The Global Distribution of COVID-19 Vaccines by the Public-Private Partnership COVAX from a Public-Law Perspective,” Leiden Journal of International Law 36/4 (2023).

[54] Ibid., p. 994.

[55] Dalberg Advisors, ACT-Accelerator Strategic Review (2021).

[56] Open Consultants, External Evaluation of the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A) (2022), https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/external-evaluation-of-the-access-to-covid-19-tools-accelerator-(act-a).

[57] Ibid.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Ibid., pp. 10–11.

[60] Ibid., p. 11.

[61] Ibid., p. 10.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Ibid., pp. 31–32.

[64] Ibid., p. 12.

[65] World Bank, “Trust Funds and Partnerships,” https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/trust-funds-and-programs.

[66] A. de Bengy Puyvallée and K. T. Storeng, “COVAX, Vaccine Donations and the Politics of Global Vaccine Inequity,” Global Health 18/26 (2022).

[67] Amnesty International, Global Initiative for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Human Rights Watch, and International Commission of Jurists, “Joint Public Statement: The Pandemic Treaty Zero Draft Misses the Mark on Human Rights” (2023), https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/IOR4064782023ENGLISH.pdf; Civil Society Alliance for the Pandemic Treaty, “Effective Participation in the Drafting of the Pandemic Treaty” (April 2002), https://www.icj.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/12-April-2022-Effective-participation-in-the-drafting-of-a-Pandemic-Treaty.pdf.

[68] World Trade Organization, Waiver from Certain Provisions of the TRIPS Agreement for the Prevention, Containment and Treatment of COVID-19: Communication from India and South Africa, IP/C/W/669 (2020).

[69] People’s Medicine Alliance, https://peoplesmedicines.org/.

[70] Open Consultants, “External Evaluation of the Access to Covid-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A)” (2022), p. 32.

[71] Civil society and community representatives to the Access to COVID-19 Tools-Accelerator (ACT-A), Letter to ACT-A Lead Agencies (2021), https://covid19advocacy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Letter-to-ACT-A-Lead-Agencies-.pdf.

[72] Erdem Türkelli (2022, see note 5); Storeng (2014, see note 22); Storeng et al. (see note 48).

[73] F. Stein, K. T. Storeng, and A. de Bengy Puyvallée, “Global Health Nonsense,” BMJ 379/o2932 (2022).

[74] WHO Pandemic Agreement, WHA78.1 (2025), art. 13.

[75] R. Habibi, M. Eccleston-Turner, and G. L. Burci, “The 2024 Amendments to the International Health Regulations: A New Era for Global Health Law in Pandemic Preparedness and Response?,” Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 53/S1 (2025).

[76] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2017, see note 43).

[77] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 24), para. 65.