Deepening Accountability: The Fair Pharma Scorecard and Access to Medicines in a Fragmented Global Health Law Landscape

EXPLORING ACCOUNTABILITY FOR HEALTH RIGHTS Vol 27/2, 2025, pp. 79-94 PDF

Rosalind Turkie and Pramiti Parwani

Abstract

The international legal landscape governing global health is characterized by regime complexity and legal fragmentation, with overlapping and sometimes conflicting legal norms. This fragmentation can blur lines of accountability, particularly in the context of access to medicines, where responsibility is dispersed across multiple stakeholders. Traditional frameworks of accountability in human rights law emphasize a vertical relationship between states as duty bearers and individuals as rights holders—failing to capture the multifaceted reality of global pharmaceutical governance, where access to medicines is shaped not only by the relevant state but also by a range of nonstate actors. Among these, pharmaceutical corporations play a pivotal role in shaping a state’s capabilities to ensure access to medicines for its population. In this context, we argue that the development and deployment of a pharmaceutical accountability scorecard offers an innovative tool to address some of the existing accountability gaps. This paper presents the Fair Pharma Scorecard – Cancer Edition, developed by the Dutch nonprofit Pharmaceutical Accountability Foundation, as an innovative tool to address some of the existing gaps. Grounded in a normative framework that draws on various international legal and health-related instruments, this scorecard evaluates the extent to which multinational pharmaceutical companies fulfill or neglect their responsibilities to ensure equitable access to medicines.

Introduction

Half of the world’s population lacks access to basic health services, including essential medicines.[1] At the forefront of this crisis are the estimated 80% of people living in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), who disproportionately bear the burden of limited access to health care.[2] In this context, cancer presents a particularly urgent challenge. It is now a leading cause of death worldwide, particularly in LMICs where under-resourced health systems are unable to absorb the high costs of (patented) cancer medicines.[3] A growing body of research on prevailing inequities in cancer health care shows that survival rates are significantly lower in LMICs, driven by late-stage diagnosis and limited access to treatments.[4]

Ensuring equitable access to (cancer) medicines is both a health care concern and a legal obligation grounded in international human rights law. The right to health, enshrined in instruments such as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), includes access to essential medicines as a core component.[5] However, the implementation and enforcement of this right is complicated by the state-centric design of international human rights law, which places the onus of accountability on governments.

Moreover, the international legal landscape governing global health is characterized by regime complexity and legal fragmentation, with overlapping and sometimes conflicting legal norms. This fragmentation can blur lines of accountability, particularly in the context of access to medicines, where responsibility is distributed across multiple and diverse stakeholders. From a human rights law perspective, traditional frameworks of accountability emphasize a vertical relationship between the state as duty bearer and the individual as rights holder. However, this model fails to capture the multifaceted reality of global pharmaceutical governance, where access to medicines is shaped not only by the relevant state but also by a range of nonstate actors. Among these, pharmaceutical corporations play a pivotal role in shaping a state’s capabilities to ensure access to medicines for its population.

In this paper, we adopt Margaret Young’s vision of “productive regime interaction” as a response to the fragmented nature of accountability in global health.[6] We build on this idea by advancing a framework of multifaceted accountability, which recognizes that obligations related to access to medicines cannot be adequately understood or enforced through a single legal or institutional lens, or by a single actor. Multifaceted accountability, in this sense, involves a range of actors beyond the traditional nation-state, including pharmaceutical companies, civil society and community actors, and other nonstate entities. It also implies that accountability mechanisms can take diverse forms, from hard-law obligations and soft-law instruments to public scrutiny and civil society-led initiatives. To exemplify this, we argue that the development and deployment of a pharmaceutical accountability scorecard offers an innovative tool to address some of the existing accountability gaps.

This paper presents the Fair Pharma Scorecard – Cancer Edition, developed by the Pharmaceutical Accountability Foundation (PAF), as a way to address these gaps. Grounded in a normative framework that draws on a range of international legal and health-related instruments, including international human rights law, authoritative soft-law instruments, and ethical principles underlying medical research, this scorecard evaluates the extent to which multinational pharmaceutical companies fulfill their human rights responsibilities to ensure equitable access to medicines.[7] We apply the scorecard to cancer medicines, where issues of access, affordability, and accountability are especially acute. We first map the legal and human rights landscape, and then highlight the limits of this state-centric model, before presenting the Fair Pharma Scorecard as an accountability mechanism that reflects the distributed nature of responsibility in global health governance and can support bottom-up norm crystallization by civil society.

The legal landscape

The human right to health and access to essential medicines

At the core of global health and access to medicines is the recognition of health as a fundamental human right.[8] Most notably, this includes the ICESCR, whose article 12 imposes a tripartite obligation on 171 state parties (excluding the United States and Cuba, among others) to respect, protect, and fulfill the right of every individual to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.[9] Article 12 on the right to health thus reflects broad global consensus on the legal imperative to advance health equity.

A key component of this right is access to essential medicines. The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, in its General Comment 14, identifies such access as a core obligation under article 12.[10] Core obligations represent a non-derogable minimum standard that states must fulfill regardless of available resources. According to the committee, the right to health should be understood not as a guarantee of being healthy but rather as the assurance of certain fundamental conditions that support a life of dignity, including access to essential medicines and health services.[11] General Comment 14 also introduces the AAAQ framework (availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality) as a standard for evaluating the adequacy of health services and goods. While general comments are not legally binding, they are widely regarded as authoritative interpretations of treaty obligations. Since this right has been widely studied, we keep this overview brief.[12]

Because only states are party to the ICESCR, the legal obligations arising out of the covenant are binding only on them. Private actors, such as pharmaceutical companies, are not directly bound by international human rights law. Their conduct is governed primarily through the lens of the appropriate state—under the ICESCR, the duty to protect obliges states to ensure that businesses under their control do not, as a minimum, undermine the right to health.[13]

However, it is now widely recognized that nonstate actors, including corporations, have responsibilities to respect human rights, though these are nonbinding. The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, adopted in 2010, clearly articulate that businesses should respect human rights and that governments must ensure compliance, including by regulating corporate conduct.[14] This position has since been echoed and expanded on by United Nations (UN) treaty bodies, including through general comments that increasingly acknowledge the growing influence of corporate actors in either facilitating or undermining the enjoyment of rights.[15] For instance, in General Comment 14, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights recognizes businesses’ responsibilities in relation to health, stressing that “while only States are parties to the Covenant and thus ultimately accountable for compliance with it, all members of society … [including] the private business sector—have responsibilities regarding the realization of the right to health.”[16] In General Comment 24, the committee further recognizes that companies may be directly linked to adverse human rights impacts through their business operations and that they bear responsibility to avoid such harms.[17] General Comment 24 elaborates on the obligations of states to protect against human rights abuses by business enterprises, calling on states to impose “strict regulations” on private providers of public services, including private health care providers, which “should be prohibited from denying access to affordable and adequate services, treatments or information.”[18]

In the context of access to medicines, Paul Hunt, during his tenure as UN Special Rapporteur on the right to health (2002–2008), was instrumental in outlining the specific responsibilities of pharmaceutical companies, which he set out in the 2008 Human Rights Guidelines for Pharmaceutical Companies in Relation to Access to Medicines (often referred to as the Hunt Guidelines).[19] The role of the UN Guiding Principles and Paul Hunt in shaping corporate accountability for health-related human rights interferences will be examined in more detail later. Before that, we shift focus to the broader legal landscape in which the right to health operates—one that is increasingly fragmented and shaped by intersecting legal regimes.

The right to health in a fragmented legal landscape

Broadly defined, global health law includes “all international legal regimes relevant to public health—international environmental law, international humanitarian and human rights law, international trade and labor law, international laws relating to arms control, and so on.”[20] Narrower interpretations of global health law restrict it to legal instruments explicitly designed to manage health threats, including the International Health Regulations, the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, and the Pandemic Agreement adopted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, while broader interpretations include a variety of international legal instruments that indirectly impact health (for instance, the World Trade Organization Agreements).[21]

Global health law can thus encompass both hard and soft law, together forming a regulatory architecture aimed at realizing the highest attainable standard of health for all.[22] It also does not exist as a unified legal regime. Rather, it operates within a fragmented and multilayered legal environment shaped by diverse actors—including states, international organizations, corporations, and civil society—and an evolving body of legal and nonlegal instruments. This landscape is marked by competing priorities. For instance, the fulfillment of the right to access medicines may be constrained by exclusive patent rights under intellectual property law, or by trade rules that limit a country’s capacity to regulate medicine prices.[23] These tensions are rarely resolved through a single legal framework and are often negotiated in political and institutional forums that differ significantly in power and influence.

This institutional and normative complexity has deep historical roots. From the latter half of the nineteenth century, a variety of intergovernmental organizations were created to govern activities with international impact—for instance, the International Telegraph Union, established in 1865; the Universal Postal Union, set up in 1874; and relevantly, the Office International d’Hygiène Publique, established in 1907, which subsequently became an early forerunner of the World Health Organization (WHO).[24] In recent decades, however, global health governance has undergone a fundamental transformation: a shift from a centrally governed international order based on political representation toward a more decentralized, pluralistic field. Public-private partnerships, philanthropic foundations, and corporate actors—particularly from the pharmaceutical industry—have taken on increasingly prominent roles. The result is a governance ecosystem characterized by a diversity of actors: research institutes, multilateral organizations, nongovernmental organizations, philanthropic institutions, Western pharmaceutical companies, generic manufacturers from the Global South, and more.[25]

This shift has profoundly changed the structure and functioning of the global public health sector. Authority and decision-making are now dispersed across a network of interdependent actors, many of whom are not formally accountable under international law. While human rights law continues to impose obligations on states, it seldom provides direct enforcement mechanisms for either public or private actors whose decisions affect access to medicines.[26] Global health governance is therefore not only legally complex but also characterized by fragmented accountability structures and fragmented or absent enforcement mechanisms. This regime complexity contributes to normative uncertainty and can undermine efforts to ensure equitable access to medicines, particularly in the face of corporate influence and market-driven imperatives.[27] The current director-general of WHO has even framed fragmentation as a barrier to the Sustainable Development Goals and achieving progress in global health.[28] The following section explores how this fragmentation in global health law contributes to the diffusion, and often dilution, of accountability for access to medicines.

Fragmentation in global health law: Legal and accountability challenges

The development of international law as a system of horizontal norms through multiple, often overlapping legal regimes has led to a phenomenon called fragmentation.[29] Fragmentation, while not inherently problematic, can become so when norms from different regimes come into conflict with one another, as there is no clear hierarchy between regimes.[30] Thus, when governments have ratified multiple international treaties and agreements, they may face difficulties implementing their obligations under one regime when these conflict with other international rules.

For example, industry actors frequently challenge the adoption of health regulations when doing so impacts trade and investment, thus limiting states’ ability to regulate health matters.[31] This is exacerbated by the fact that the enforceability of global health standards is limited, particularly when contrasted with the robust mechanisms available for enforcing international economic law.[32] International trade law under the auspices of the World Trade Organization (WTO) has, for instance, traditionally been characterized by a compulsory dispute settlement mechanism and retaliation measures in case a WTO member does not comply with a ruling—although the system has come under threat in recent years due to a crisis at the WTO Appellate Body.[33] Regardless, a regulatory imbalance between global health governance and international economic law continues to persist, weakening the protection of human rights, especially the right to health, which is threatened by corporate activities prioritizing economic gains over health and well-being.[34] Consequently, accountability in global health becomes fragmented, with responsibility dispersed among multiple actors.

Of relevance for this paper, responsibility for access to medicines is similarly distributed across a complex array of actors, including states, international organizations, and nonstate actors such as pharmaceutical corporations. While corporations increasingly play a decisive role in shaping access to medicines, human rights accountability mechanisms have not evolved to reflect this complexity. Traditional accountability mechanisms under human rights law, through UN treaty bodies, the Universal Periodic Review process, and Special Procedures such as the Special Rapporteur on the right to health, are state-centric. The role of private actors is seen largely through the lens of the concerned state, which is obliged to ensure that the private actors under its control do not violate human rights.[35] This model is premised on a vertical relationship between states and individuals and assumes state control and capacity to deliver on its obligations.

Consequently, even though pharmaceutical companies exercise considerable control over the availability, pricing, and distribution of medicines, they still remain largely outside the scope of binding international and human rights obligations. Attempts to address this accountability gap, such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the Hunt Guidelines for pharmaceutical companies, have contributed useful soft-law frameworks.[36] Still, these remain voluntary and unenforceable, offering no real recourse when corporate actions interfere with the right to health. In the context of access to medicines, this interplay between multiple legal regimes, institutional actors, and competing norms blurs lines of accountability.

In 2006, the International Law Commission examined the issue of fragmentation within international law.[37] One of its conclusions was that fragmentation could be addressed, in part, by “interpreting treaties in accordance with other relevant rules and principles that apply between the parties” (including human rights), an approach known as systemic integration or interpretation. Building on this, Young has proposed the idea of a “legal framework for regime interaction” to manage fragmentation.[38] She argues that the interaction between different legal regimes can generate “productive friction,” potentially resulting in a more adaptive and effective international legal system than what each regime could achieve on its own. Given its inherently cross-cutting nature, global health law is uniquely positioned to serve as a bridge between normative divides and to address fragmentation. In sum, the fragmentation of international law and the inadequacy of existing accountability structures are mutually reinforcing. Together, they enable powerful actors to evade responsibility, hinder the realization of the right to health, and weaken efforts to ensure equitable access to medicines. Addressing these dual challenges will require not only legal reform but also the development of new accountability mechanisms that can hold both states and private actors accountable within a more integrated global health governance framework.

Since Young’s foundational work, scholarship has further explored how weak accountability and fragmented governance shape global health outcomes. Neil Spicer et al. demonstrate that “unbalanced accountability” (strong upward reporting to high-income donors versus weak downward accountability to recipient countries) exacerbates fragmentation and limits coordination between global health actors.[39] Gisela Hirschmann introduces the concept of “pluralist accountability,” emphasizing how third-party actors, including nongovernmental organizations, courts, and networks, can hold both public and private actors accountable outside of formal delegation structures, often by leveraging reputational pressure and benchmarking.[40] Akiko Kato and Yoshiko Naiki also highlight the role of nongovernmental organizations in improving access to medicines by fostering “polycentric governance,” where multiple state and nonstate actors interact and where indicators and rankings (such as the Access to Medicine Index) can act as practical regulatory tools that influence behavior and encourage corporate responsibility.[41] Similarly, Judith Kelley and Beth Simmons show how indicators can influence policy through the pressure of comparison.[42]

Together, these insights show how fragmentation, accountability gaps, and intersecting governance structures create both challenges and opportunities.

Scorecards and benchmarking: Practical tools for accountability

Since traditional, state-centric human rights accountability mechanisms fall short in addressing the dispersed and fragmented responsibilities of private actors in ensuring equitable access to medicines, alternative forms of accountability are needed to create a more integrated and responsive governance framework.[43] We argue that scorecards and benchmarking offer practical tools for social accountability where formal legal mechanisms are inadequate for holding nonstate actors accountable.[44]

This approach aligns with the International Law Commission’s view of “special regimes,” where regimes are defined not only by state actors but by their functional specialization.[45] This implies that the goals, norms, and activities of nonstate actors are integral to regime formation and evolution. Thus, the influence of technical experts, nongovernmental organizations, regional and international courts (such as the European Court of Human Rights, the WTO panels, etc.), and other nonstate participants must be considered when analyzing regime interaction. These actors shape the dynamics of governance and accountability and are therefore essential to building more inclusive and adaptive frameworks for global health governance.

Moreover, civil society organizations are not constrained by the same boundaries between regimes or hierarchies of norms that often limit state-based actors. Tools such as scorecards operate not in opposition to legal mechanisms but in the gaps between fragmented regimes, providing a practical means of promoting accountability and norm convergence. In this way, they illustrate how the complexity of global health governance can be harnessed to develop more effective accountability structures. This also reflects Young’s concept of productive friction between legal and normative systems, where competing systems can generate innovative governance responses by exposing tensions and gaps between them.

Therefore, scorecards, especially those developed by civil society organizations, can serve as critical tools for addressing the accountability gap by creating structured, evidence-based, and citizen-informed assessments of corporate behavior.[46] We present the Fair Pharma Scorecard as an example of how civil society can evaluate pharmaceutical companies on their alignment with human rights norms relating to access to medicines. In doing so, we show how scorecards offer new, practical means for shifting the locus of accountability beyond traditional state institutions, enabling broader stakeholder engagement and public oversight.[47]

We first draw on the conceptualization of social accountability embraced in the public services and development literature. Social accountability has been defined as “an approach towards building accountability that relies on civic engagement, i.e., in which it is ordinary citizens and/or [civil society organizations] who participate directly or indirectly in exacting accountability.”[48] Originating in the early 2000s to refer to community-led initiatives to hold governments accountable outside of only election-based systems, the term has since evolved to encompass a diverse range of citizen-led initiatives, such as community scorecards, citizen report cards, participatory budgeting, and social audits.[49] A common element across these mechanisms is the emphasis on citizen agency and oversight. While social accountability has traditionally been oriented toward control over, and accountability of, public sector institutions, we argue for an expansion of these mechanisms to include the private sector, particularly pharmaceutical companies whose actions bear significant implications for public health and human rights.

There is a long history of indicators, benchmarks, and scorecards in business and human rights. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, scholars and policy makers explored standardized approaches to holding corporations accountable.[50] As a result, scorecards and ratings, including those created by civil society organizations, have emerged as promising innovations in the business and human rights landscape.[51] In the sphere of medicines access, the Access to Medicine Index is a notable example.[52] Early initiatives addressing corporate responsibility in a broader context include the 1999 UN Global Compact, which encouraged companies to evaluate their conduct in light of human rights principles, including the ICESCR.[53] The Global Compact ushered in a new standard of corporate conduct being benchmarked against international law.[54] The UN Working Group on the Issue of Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises has also highlighted the key role of indicators in holding corporations accountable for their impact on human rights, noting the desirability of “establishing measurable and transparent indicators to assess [the] effective implementation” of the UN Guiding Principles.[55]

Importantly, scorecards and other indicators for monitoring corporate human rights impacts are not merely technical tools; they also contribute to the creation and evolution of new norms through processes of interaction, interpretation, and practice among diverse normative communities.[56] Over time, repeated use and convergence around certain indicators may contribute to norm crystallization—that is, the transformation of soft or emerging standards into more widely accepted and authoritative norms, especially when these benchmarks begin to guide state behavior, corporate conduct, and stakeholder expectations in consistent and predictable ways. The Access to Medicine Index published by the Access to Medicine Foundation is a good example of this: “board-level responsibility for access to medicines”—one of the indicators assessed in the index—was initially rare in 2008–2010 but became standard practice by the 2020s. The index continues to include the indicator, but it functions more as a baseline expectation or “accepted practice.”[57]

Finally, numerical-based indicators such as scorecards, benchmarks, and ratings offer several advantages. Companies are often driven by reputational concerns to join and comply with these indicators, since their profits and share values are acutely responsive to public perception.[58] Scorecards, often grounded in naming-and-shaming strategies, can therefore be powerful drivers of corporate compliance, sometimes more effective than state regulation. They also provide clear, accessible information that allows easy comparison and ranking of companies.[59]

The Fair Pharma Scorecard – Cancer Edition

Building on the precedent set by the Fair Pharma Scorecard for COVID-19 products, PAF is currently developing a methodology to evaluate how multinational pharmaceutical companies fulfill their responsibilities to ensure equitable access to cancer medicines.[60] Funded by the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF Kankerbestrijding), this new initiative focuses on a subset of essential cancer therapies selected from the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, ensuring alignment with global priority-setting processes.

Cancer is a leading and increasing global cause of death, with new cases and deaths projected to rise by 60%–70% by 2040 compared to 2018.[61] Despite this growing need for treatment, access to cancer medicines remains deeply unequal. In LMICs, many patients lack access to even the most basic cancer medicines, while in high-income countries, new drugs are often launched at unsustainably high prices, straining even robust and (comparatively) well-resourced health systems.[62] This inequality in access to treatment severely affects survival rates: WHO estimates that over 80% of children with cancer in high-income countries will be cured, compared to 10% in LMICs, which bear nearly 80% of the global cancer burden but receive less than 5% of resources for combating the disease.[63] Given the scale, urgency, and inequity of the cancer burden, ensuring affordable and equitable access to treatment is a global health and human rights imperative—and the driving reason behind this scorecard.

The Fair Pharma Scorecard on access to cancer medicines serves three core purposes: first, to empower procurers of cancer medicines (governments, international agencies, or other buyers) with transparent, product-specific insights that support stronger price negotiations and better affordability; second, to act as a tool encouraging pharmaceutical companies to adopt more equitable and consistent access practices across their cancer treatment portfolios by setting standards and exposing (un)fair behaviors; and third, to inform and guide the development of stronger, evidence-based legal and policy frameworks at national, regional, and international levels, promoting system-level improvements in equitable access to essential cancer therapies.

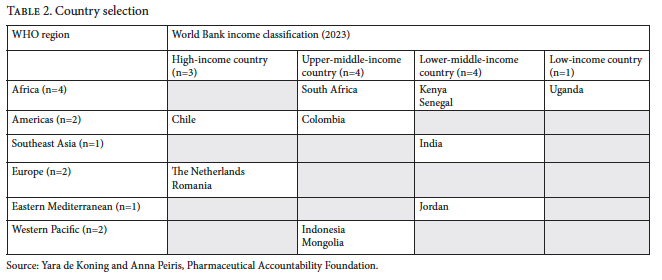

Here, we present the methodology for the cancer scorecard, explaining the normative basis behind the criteria and the basis for scoring. The scorecard evaluates the behavior of 15 companies across 18 cancer medicines within 12 countries. Countries were chosen to ensure representation across WHO geographic regions and income groups, while also considering the availability of data in each of these countries. While final product selection is to be confirmed, it will include all cancer medicines listed on the 2025 WHO Model List of Essential Medicines that remain under primary or secondary patent protection. The final set of companies to be evaluated will be determined based on this product selection.

While a detailed discussion about product, company, and country selection falls beyond the scope of this paper, it is relevant to note that companies are scored per product, not overall, in an effort to acknowledge that corporate behavior can vary by product. This approach enables us to identify whether there are inconsistencies in corporate behavior and if so, how to interpret these differing practices.

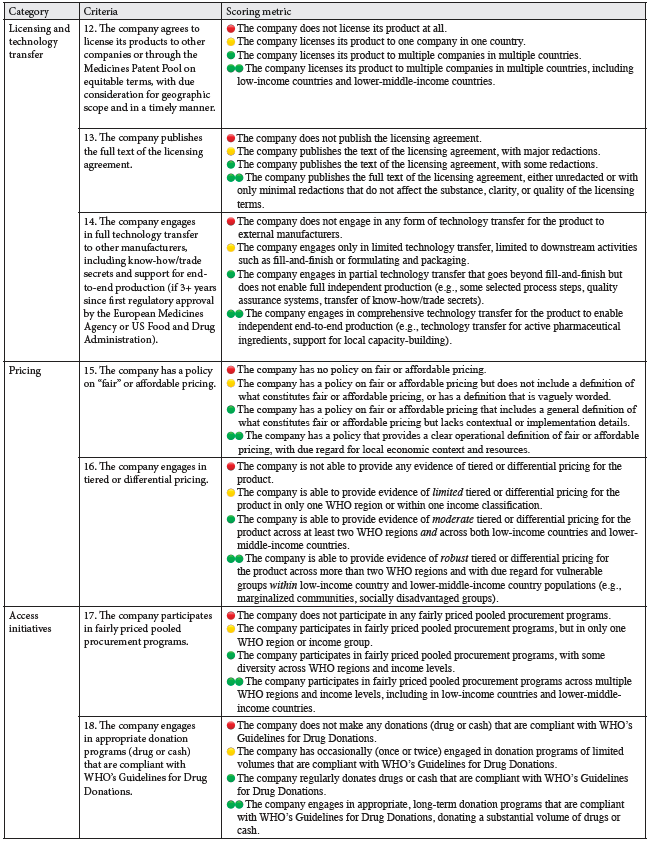

The methodology was developed by a team of human rights lawyers in consultation with a multidisciplinary scientific advisory committee and a feedback group comprising academics, legal experts, access-to-medicines advocates, representatives from the Dutch Cancer Society, and experts in pharmaceutical policy. This consultative process was central to the methodology’s normative legitimacy and the scorecard’s interdisciplinary nature, integrating perspectives from public health, law, and policy. All dimensions of the methodology were developed independently of pharmaceutical companies and governments. The final methodology consists of a structured framework that scores pharmaceutical companies across 18 criteria, grouped into six thematic categories: (1) commitments and accountability, (2) transparency, (3) regulatory systems, (4) licensing and technology transfer, (5) pricing, and (6) access initiatives. Each category operationalizes key dimensions of the corporate responsibility to respect.

Table 1 outlines the 18 criteria across the six thematic categories, along with the scoring metric for each criteria, while Table 2 displays the country selection.

Company behavior will be assessed on a four-point scale, following a modified traffic light system: red for non-compliant behavior or inadequate disclosure; yellow for partially compliant behavior; green for compliant behavior; and double green for excellent behavior that forms good practice. Numerical values are assigned to each score (double green = 3, green = 2, yellow = 1, red = 0), and a company’s total score is calculated by dividing the cumulative points by the number of criteria. Each criterion is weighted equally.

Data will be drawn from a combination of company responses and publicly available sources. A questionnaire will be sent to companies, allowing them to provide relevant information. This will be complemented with publicly available data from company websites, filings, annual reports, and public databases, including information on country registrations, licensing agreements, and clinical trials. Given the significance of transparency as a foundational element influencing the effectiveness of the other criteria, the public availability of relevant data is crucial and will inform how companies score on these criteria.

The normative foundation underpinning this framework draws from a composite of binding and nonbinding sources: international human rights law, authoritative soft-law instruments, national and regional legal frameworks, internationally accepted ethical principles, and established best practices from pharmaceutical companies themselves, all grounded within a broader framework of public health and health care considerations. The legal sources referred to in the design of the methodology include the ICESCR, General Comment 14 and General Comment 24 of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the UN Guiding Principles, the 2008 Hunt Guidelines, World Health Assembly resolutions relevant to access to medicines, various UN declarations and political commitments, and ethical standards such as the Helsinki Declaration.[64]

The process of developing the indicators was therefore inherently normative and designed to contribute to norm crystallization. By explicitly linking each category and criterion to these legal and normative sources, this scorecard is intended not only as a benchmarking tool but also as a vehicle for articulating and advancing an emerging consensus on the responsibilities of pharmaceutical companies in global health.[65] Its aim is to embed these expectations within a transparent, independent and methodologically robust framework capable of informing both corporate practice and public advocacy efforts.

Building on this normative foundation, the scorecard proposes a new form of accountability that extends beyond traditional legal enforcement mechanisms. This approach acknowledges the gaps in existing international human rights frameworks in regulating corporate behavior and offers a complementary tool that leverages evidence-based evaluations to drive corporate responsibility by empowering civil society and other stakeholders to assess and publicly report on pharmaceutical companies’ performance. In doing so, it fosters a broader accountability ecosystem that engages a diverse range of stakeholders, from patients and advocates to policy makers and the general public. The scorecard thus forms one of several mechanisms—from legal obligations to civil society initiatives—that must collectively be deployed in a coordinated manner to effectively hold pharmaceutical companies accountable within the current fragmented global health landscape.

Limitations

While scorecards hold potential as tools for accountability, important caveats remain. Scorecards draw their legitimacy from the authority of their creator, as well as their substantive content. Further, due to the often limited availability of data, these scorecards may rely on partial data that are standardized for the sake of comparison, risking distorted or incomplete results through reductive metrics.[66]

Another important consideration is whether individuals and communities that are most tangibly impacted by the relevant corporate conduct are actively engaged in the process of creating and applying these indicators—otherwise, the voices of rights holders, especially disadvantaged individuals and communities, may be marginalized.[67] Advocacy-oriented civil society organizations and technical experts play key roles in this process, but this should not come at the expense of affected individuals and communities, who, in the case of pharmaceuticals access, include patient groups, especially in Global South countries.[68] This aligns with the human rights principle of participation and is reinforced by initiatives such as the WHO Framework for Meaningful Engagement of People Living with Noncommunicable Diseases and Mental Health and Neurological Conditions.[69] As noted by Nora Götzmann, “it is a fundamental principle of democracy that people are entitled to participate in decisions that affect them.”[70] However, she also finds that this consultation can be limited in human rights impact assessments, where it often occurs only after decisions have been made. To remedy this, she recommends that “rather than stakeholder consultation being just one of the impact assessment stages, [human rights impact assessments need] to make provisions for the inclusive participation of rights holders at critical points throughout the whole assessment process.” This should also take into consideration “the power dynamics at play within communities, between rights holders, companies and state actors, as well as with regard to the persons comprising the assessment team.”[71] Another caveat mentioned by Götzmann is that “the extent to which such assessments actually facilitate processes and outcomes that effectively address the adverse human rights impacts of business activities remains largely unknown.”[72] Further research is therefore needed on both the quality of rights holder participation and the tangible impact of human rights impact assessments, including how they influence decision-making, strengthen accountability, and address power asymmetries in business and human rights practice.

Conclusion

Civil society-led scorecards such as the PAF Fair Pharma Scorecard can become a valuable and innovative tool to advance pharmaceutical accountability in global health. By integrating interdisciplinary perspectives and explicitly linking indicators to legal and normative frameworks, the scorecard may function both as a benchmarking mechanism and as a catalyst for norm crystallization around the responsibilities of pharmaceutical companies. This approach supports the need for a multifaceted accountability ecosystem that engages diverse stakeholders and mechanisms beyond the state to ensure equitable access to medicines. Cancer offers a salient case that exemplifies the necessity for such novel frameworks.

The scorecard is designed for three key functions: empowering medicine procurers with product-specific data; driving corporate behavior change through advocacy; and informing legal and policy development at multiple governance levels. The combined operation of all three is essential to catalyze meaningful, systemic change. By navigating the interstices of international human rights law, public health frameworks, and emerging soft-law norms, scorecards have the potential to harness the tensions between these regimes to forge new forms of accountability better suited to hold private actors responsible for their human rights obligations. In this manner, the scorecard presents an example of Young’s concept of “productive friction,” where regime complexity and interaction lead to the development of new governance mechanisms, reflecting a shift toward more effective and equitable accountability among global health actors. Furthermore, scorecards can contribute to bottom-up norm crystallization, as civil society reinforces emerging expectations of pharmaceutical companies through public pressure and advocacy, transforming evolving societal standards into concrete standards of companies’ human rights responsibilities.

Ultimately, scorecards are an important and evolving part of the accountability ecosystem. Their value lies not only in benchmarking performance but in deepening a new paradigm of public accountability through which businesses are held to their human rights responsibilities. On their own, however, scorecards cannot deliver systemic transformation; sustainable change requires strengthening and expanding legal mechanisms to a wider range of actors, reflecting the growing role of corporations in shaping global health outcomes. Without structural change, the potential of scorecards remains inherently limited.[73] The real challenge, then, is to channel the momentum generated by scorecards toward lasting structural reform. Embedded within broader reforms, scorecards can act as powerful catalysts, transforming reputational pressure into systemic change and advancing meaningful corporate accountability for the right to health.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our thanks to Katrina Perehudoff, Hans Hogerzeil, and James Hazel for their valuable feedback on the scorecard methodology.

Funding

The research for this paper was funded by the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF Kankerbestrijding).

Rosalind Turkie, LLM, is an independent consultant and researcher in access to medicines and human rights based in Toulouse, France. She is consulting with the Pharmaceutical Accountability Foundation for the Fair Pharma Scorecard – Cancer Edition, funded by the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF Kankerbestrijding).

Pramiti Parwani, PhD, is a research fellow at Law for Health and Life, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands. She is consulting with the Pharmaceutical Accountability Foundation for the Fair Pharma Scorecard – Cancer Edition, funded by the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF Kankerbestrijding).

Competing interests: None declared.

Please address correspondence to Rosalind Turkie. Email: rosalind.turkie@gmail.com.

Copyright © 2025 Turkie and Parwani. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

[1] World Health Organization, Tracking Universal Health Coverage: 2023 Global Monitoring Report (2023).

[2] World Health Organization, Emergency Medical Teams: 2030 Strategy (2023); World Health Organization, Access to Safe, Effective and Quality-Assured Health Products and Technologies: Roadmap for WHO Action 2025–2030 (2025).

[3] World Health Organization, Technical Report: Pricing of Cancer Medicines and Its Impacts (2018); see also P. O. Mattila, R. Ahmad, S. S. Hasan, and Z. Babar, “Availability, Affordability, Access, and Pricing of Anti-Cancer Medicines in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review,” Frontiers in Public Health 9 (2021).

[4] S. Vaccarella, J. Lortet-Tieulent, R. Saracci, et al., “Reducing Social Inequalities in Cancer: Evidence and Priorities for Research,” IARC Scientific Publications No. 168 (2019); H. Gelband, R. Sankaranarayanan, C. L. Gauvreau, et al., “Costs, Affordability, and Feasibility of an Essential Package of Cancer Control Interventions in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: Key Messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition,” Lancet 387/10033 (2016).

[5] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI) (1966); Convention on the Rights of the Child, G.A. Res. 44/25 (1989); Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, G.A. Res. 61/106 (2006); International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, G.A. Res. 2106A (XX) (1965); Constitution of the World Health Organization (1946); United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, G.A. Res 61/295 (2007).

[6] M. A. Young (ed), Regime Interaction in International Law: Facing Fragmentation (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

[7] Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (2011); United Nations General Assembly, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health, UN Doc. A/63/263 (2008); World Medical Association, Declaration of Helsinki: Medical Research Involving Human Participants (2024).

[8] Constitution of the World Health Organization (see note 5); Universal Declaration of Human Rights, G.A. Res. 217A (III) (1948), art. 25.

[9] United Nations Human Rights Treaty Bodies, “View the Ratification Status by Country or by Treaty,” https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/treaty.aspx?treaty=cescr&lang=en; International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see note 5), art. 12.

[10] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000).

[11] Ibid., para. 41(d).

[12] L. Forman, B. Al-Alami, and K. Fajber, “An Inquiry into State Agreement and Practice on the International Law Status of the Human Right to Medicines,” Health and Human Rights 24/2 (2022); S. K. Perehudoff and L. Forman, “What Constitutes ‘Reasonable’ State Action on Core Obligations? Considering a Right to Health Framework to Provide Essential Medicines,” Journal of Human Rights Practice 11/1 (2019).

[13] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 24, UN Doc. E/C.12/GC/24 (2017), paras. 33, 37.

[14] Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (see note 7).

[15] Human Rights Committee, General Comment No. 31, UN Doc. CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.13 (2004); Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2017, see note 13).

[16] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 10), para. 42.

[17] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2017, see note 13).

[18] Ibid., para. 21.

[19] J-Y. Lee and P. Hunt, “Human Rights Responsibilities of Pharmaceutical Companies in Relation to Access to Medicines,” Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 40/2 (2012); United Nations General Assembly (2008, see note 7).

[20] J. P. Ruger, “Normative Foundations of Global Health Law,” Georgetown Law Journal 96/2 (2008).

[21] Ibid.; World Health Organization, International Health Regulations (2005), 3rd edition; Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, 2302 UNTS 166 (2003); World Health Organization, Resolution 78.1 (2025).

[22] B. M. Meier and A. Finch, “Seventy-Five Years of Global Health Lawmaking Under the World Health Organization: Evolving Foundations of Global Health Law Through Global Health Governance,” Journal of Global Health Law 1/1 (2024).

[23] Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, 1869 UNTS 299 (1994); see, for instance, P. Cullet, “Patents and Medicines: The Relationship Between TRIPS and the Human Right to Health,” International Affairs 79/1 (2003).

[24] International Telegraph Union, https://www.itu.int/en/about/Pages/default.aspx; Universal Postal Union, https://www.upu.int/en/home. See also F. Lyall, International Communications: The International Telecommunication Union and the Universal Postal Union (Routledge, 2016); N. Howard-Jones, “The World Health Organization in Historical Perspective,” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 24/3 (1981).

[25] J. Lidén, “The World Health Organization and Global Health Governance: Post-1990,” Public Health 128/2 (2014); L. O. Gostin and B. Mason Meier (eds), Global Health Law and Policy: Ensuring Justice for a Healthier World (Oxford University Press, 2023).

[26] See P. Parwani, “From Human Rights to the Pandemic Agreement and Beyond: Reframing Vaccines Access Through a Framework of ‘States’ Capabilities’,” Journal of Global Health Law 2/1 (2025).

[27] A. B. Gilmore, A. Fabbri, F. Baum, et al., “Defining and Conceptualising the Commercial Determinants of Health,” Lancet 401/10383 (2023); N. Spicer, I. Agyepong, T. Ottersen, et al., “‘It’s Far Too Complicated’: Why Fragmentation Persists in Global Health,” Globalization and Health 16/1 (2020).

[28] World Health Organization, Towards a Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-Being for All: Uniting to Accelerate Progress Towards the Health-Related SDGs (2018); Spicer et al. (see note 27).

[29] International Law Commission, Fragmentation of International Law: Difficulties Arising from the Diversification and Expansion of International Law, UN Doc. A/CN.4/L.682 (2006).

[30] M. den Heijer and H. van der Wilt, “Jus Cogens and the Humanization and Fragmentation of International Law,” in M. den Heijer and H. van der Wilt (eds), Netherlands Yearbook of International Law 2015: Jus Cogens: Quo Vadis? (Asser Press, 2016).

[31] See generally H. Jarman, “Attack on Australia: Tobacco Industry Challenges to Plain Packaging,” Journal of Public Health Policy 34/3 (2013); B. Hawkins and C. Holden, “A Corporate Veto on Health Policy? Global Constitutionalism and Investor-State Dispute Settlement,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 41/5 (2016).

[32] See, e.g., the WTO dispute settlement mechanism: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/disp_settlement_cbt_e/intro1_e.htm.

[33] W. J. Davey, “WTO Dispute Settlement: Crown Jewel or Costume Jewelry?,” World Trade Review 21/3 (2022); O. Starshinova, “Is the MPIA a Solution to the WTO Appellate Body Crisis?,” Journal of World Trade 55/5 (2021); S. Joseph, Blame it on the WTO? A Human Rights Critique (Oxford University Press, 2011), ch. 3.

[34] See generally S. Joseph, “Human Rights and the World Trade Organization: Not Just a Case of Regime Envy,” SSRN 1316760 (2008).

[35] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2017, see note 13); for a discussion on how various actors shape a state’s opportunity to ensure access to medicines for its people, see Parwani (see note 26).

[36] United Nations General Assembly (2008, see note 7); Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (see note 7).

[37] International Law Commission (see note 29).

[38] Young (see note 6).

[39] Spicer et al. (see note 27).

[40] G. Hirschmann, Accountability in Global Governance (Oxford University Press, 2020).

[41] A. Kato and Y. Naiki, “The Access to Medicine Index: How Ranking Pharmaceutical Companies Encourages Polycentric Health Governance,” Health Policy 125/11 (2021).

[42] J. Kelley and B. Simmons, “Introduction: The Power of Global Performance Indicators,” International Organization 73/3 (2019).

[43] L. Forman, C. Correa, and K. Perehudoff, “Interrogating the Role of Human Rights in Remedying Global Inequities in Access to COVID-19 Vaccines,” Health and Human Rights 24/2 (2022); A. Ramasastry, “Corporate Social Responsibility Versus Business and Human Rights: Bridging the Gap Between Responsibility and Accountability,” Journal of Human Rights 14/2 (2015).

[44] D. de Felice, “Business and Human Rights Indicators to Measure the Corporate Responsibility to Respect: Challenges and Opportunities,” Human Rights Quarterly 37/2 (2015); J. Harrison and S. Sekalala, “Addressing the Compliance Gap? UN Initiatives to Benchmark the Human Rights Performance of States and Corporations,” Review of International Studies 41/5 (2015).

[45] International Law Commission (see note 29).

[46] S. E. Merry, The Seductions of Quantification: Measuring Human Rights, Gender Violence, and Sex Trafficking, (University of Chicago Press, 2016); M. Bexell, “Ranking for Human Rights? The Formative Power of Indicators for Business Responsibility,” Journal of Human Rights 21/5 (2022).

[47] Bexell (see note 46).

[48] C. Malena, R. Forster, and J. Singh, “Social Accountability: An Introduction to the Concept and Emerging Practice,” Social Development Papers No. 76 (World Bank, 2004); J. M. Ackerman, “Human Rights and Social Accountability,” Social Development Papers No. 86 (World Bank, 2005).

[49] A. Joshi, “Legal Empowerment and Social Accountability: Complementary Strategies Toward Rights-Based Development in Health?,” World Development 99 (2017), p. 161; Ackerman (see note 48).

[50] Ramasastry (see note 43).

[51] De Felice (see note 44).

[52] Access to Medicine Foundation, “2024 Access to Medicine Index” (November 19, 2024), https://accesstomedicinefoundation.org/resource/2024-access-to-medicine-index.

[53] United Nations Global Compact, “The Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact,” https://unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles; Ramasastry (see note 43).

[54] Ramasastry (see note 43).

[55] C. M. Carrasco, “The UNGPs: What Contribution Are the National Action Plans Making?,” in A. Marx, G. van Calster, J. Wouters, et al. (eds), Research Handbook on Global Governance, Business and Human Rights (Edward Elgar, 2022); United Nations General Assembly, Report of the Working Group on the Issue of Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises, UN Doc. A/67/285 (2012), para. 79.

[56] RightsBusiness, “Towards a Business and Human Rights Index and Accreditation and Certification Scheme for Business Enterprises: An Introductory Paper” (2013), https://media.business-humanrights.org/media/documents/files/media/documents/rightbusiness-paper-jul-2013.pdf; de Felice (see note 44), pp. 536–537; E. Partiti, “Polycentricity and Polyphony in International Law: Interpreting the Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights,” International and Comparative Law Quarterly 70/1 (2021).

[57] Access to Medicine Foundation, First Independent Ten-Year Analysis: Are Pharmaceutical Companies Making Progress When It Comes to Global Health? (2019).

[58] N. Bernaz, Business and Human Rights: History, Law and Policy: Bridging the Accountability Gap (Routledge, 2016), p. 92.

[59] Merry (see note 46).

[60] See Fair Pharma Scorecard, “Fair Pharma Scorecard: COVID-19 Edition,” https://fairpharmascorecard.org/.

[61] International Agency for Research on Cancer, “Predictions of the Future Cancer Incidence and Mortality Burden Worldwide up Until 2050,” https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/home.

[62] Mattila et al. (see note 3); for high-income examples, see, e.g., Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal, “Brief van de Minister van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport” (December 15, 2023), https://www.tweedekamer.nl/kamerstukken/brieven_regering/detail?id=2023Z20312&did=2023D49629.

[63] World Health Organization (2018, see note 3).

[64] World Medical Association, Declaration of Helsinki: Medical Research Involving Human Participants (2024). Examples of UN declarations and political commitments include United Nations General Assembly, Progress on the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases: Report of the Secretary-General, UN Doc. A/72/662 (2017); United Nations General Assembly, Political Declaration of the 3rd High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases, UN Doc. A/RES/73/2 (2018).

[65] See generally de Felice (see note 44).

[66] Bexell (see note 46); J. Lie, “Performing Compliance with Development Indicators: Brokerage and Transnational Governance in Aid Partnerships,” Social Anthropology 28/4 (2020).

[67] Ackerman (see note 48), p. 10.

[68] De Felice (see note 44), p. 515.

[69] World Health Organization, WHO Framework for Meaningful Engagement of People Living with Noncommunicable Diseases and Mental Health Conditions (2023).

[70] N. Götzmann, “Human Rights Impact Assessment of Business Activities: Key Criteria for Establishing a Meaningful Practice,” Business and Human Rights Journal 2/1 (2017), p. 99.

[71] Ibid.

[72] Ibid., p. 88.

[73] Bexell (see note 46).