A Hard Pill to Swallow: Pharmacy Chain Dominance and the Commodification of Mental Health in Peru

INSTITUTIONAL CORRUPTION AND HUMAN RIGHTS IN MENTAL HEALTH, Vol 27/2, 2025, pp. 243-257 PDF

Alberto Vásquez Encalada

Abstract

Peru’s mental health system remains marked by chronic underinvestment, fragmentation, and weak regulation, leaving many without adequate access to care. In this context, private pharmacy chains have become central actors in the provision of mental health services, functioning as de facto points of access for psychotropic medications. Drawing on the concept of institutional corruption and a rights-based analysis, this paper examines how their dominance has transformed access to psychotropic medication into a market-controlled process in which commercial interests shape treatment pathways, reinforcing inequality and overmedicalization and undermining the right to health.

Introduction

Peru’s public health system has long struggled with underinvestment, fragmentation, and structural inefficiencies, leaving vast segments of the population without adequate care.[1] These challenges are particularly acute in the field of mental health, where services remain scarce, geographically uneven, and under-resourced.[2] The implementation of community-based mental health reforms in recent years, although significant at the policy level, has yet to shift the system away from biomedical approaches or meet the minimum standards of availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality outlined in the international right to health framework.[3]

In this landscape, private pharmacy chains have emerged as central actors in the provision of mental health care. For many Peruvians, especially in underserved areas, pharmacies and boticas (drugstores) serve not only as dispensaries but also as the first and often only point of contact with the health care system.[4] People frequently bypass formal consultations, relying instead on over-the-counter medications and informal advice from pharmacy staff.[5] These private pharmacies operate in a market dominated by two conglomerates that control most of the retail sector. They influence pricing, promote branded and private-label medications over affordable generics, and benefit from regulatory gaps that allow for commercial practices with limited oversight. In the absence of strong public provision or regulatory enforcement, pharmacies have accrued significant power over what medicines are available, how they are dispensed, and at what price.

This paper argues that the growing dominance of pharmacy chains in Peru reflects a broader process of regulatory capture and structural conflicts of interest, analyzed through the lens of institutional corruption. In this context, both illegal and legally permitted but ethically problematic practices can distort public health goals and prioritize commercial interests over equitable mental health care. The paper examines how these actors shape access to medication, reinforce inequalities, and operate within a context of weak state oversight. In Peru, pharmacies and boticas function similarly as retail outlets for medications—the key difference being that pharmacies must be owned by a professional pharmacist, although both are legally required to operate under the technical direction of one. For simplicity, the term “pharmacies” is used throughout the paper to refer to both. The analysis draws on the international right to health framework and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) to assess state obligations and the impact of market-driven practices on equitable access to mental health care.

This paper is based on a critical synthesis of secondary sources rather than primary empirical research. It draws on academic literature, legal and policy documents, regulatory decisions, and investigative journalism published between 2010 and 2025, identified through targeted searches in PubMed, SciELO, Google Scholar, and official Peruvian databases. While not a comprehensive empirical study, the paper builds a rights-based analysis through the critical synthesis of existing evidence and case examples to illuminate structural dynamics and contribute to discussions on institutional corruption in health governance. Findings depend on the availability and quality of existing data, and information gaps—especially on private pharmacy operations—remain significant.

Mental health care in Peru: Context and challenges

Mental health care in Peru has historically faced significant barriers, characterized by inadequate infrastructure, insufficient resources, and fragmented service delivery.[6] Over the past decade, however, there has been a marked shift in policy and investment, with the adoption of a community-based mental health model centered on human rights, universal health coverage, and decentralized care.[7] Aimed at serving the entire population—particularly those with moderate to severe conditions—this reform has led to the creation of 291 community mental health centers, 94 protected housing facilities, 54 specialized hospital units, and the nationwide deployment of multidisciplinary teams.[8]

Despite these advances, implementation remains uneven, and gaps in coverage and quality persist. Public mental health facilities are still concentrated mainly in Lima and other urban centers, leaving rural and remote regions severely underserved. The national treatment gap remains high, with an estimated 72.4% of people needing mental health care not receiving it.[9] While public investment in mental health increased by 223.7% between 2015 and 2022—an average annual growth of 16%—mental health still represented only 2.6% of the total health budget in 2023, well below the 10% benchmark recommended by the World Health Organization.[10]

A persistent shortage of trained personnel further compromises the quality of services. The number of psychologists in primary care has considerably increased, but the availability of mental health specialists remains inadequate, especially in non-urban areas.[11] In many regions, the existing infrastructure and human resources are still insufficient to meet growing demand. Furthermore, the continued dominance of a biomedical and custodial approach in professional education and clinical practice undermines efforts to shift toward more community-based, rights-oriented care models.[12]

In addition, public mental health facilities face persistent shortages of psychotropic medications. Both community mental health centers and psychiatric hospitals report recurring difficulties in maintaining a stable supply of drugs such as antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers.[13] These shortages stem from chronic delays in procurement, coordinated by the Ministry of Health. When procurement processes break down, hospitals often resort to direct purchases, typically at higher prices.[14] The Ministry of Health has identified these delays as a significant bottleneck in scaling up mental health services.[15] These stock ruptures disrupt treatment continuity and disproportionately affect low-income users who depend on public services.

These systemic barriers have had a direct impact on access to mental health care, particularly for individuals who rely on medication as their primary form of treatment. In the absence of consistent availability of psychotropic drugs in public facilities, many are forced to purchase them out of pocket from private pharmacies, where generic options are often unavailable.[16] The financial burden this imposes on households is significant. For example, a monthly treatment with brand-name antidepressants such as fluoxetine or sertraline can cost the equivalent of 8.5 to 19.2 days of work, while even generic options may require more than five days of wages.[17] These expenditures far exceed national averages.[18] As will be explored further in this paper, in some cases, the price difference between generics and branded drugs is negligible, further undermining affordability.

Recent data from the Ministry of Health show that although out-of-pocket spending is concentrated largely on medications not listed as essential by the Ministry of Health, more than half of all units consumed correspond to essential medicines that, in principle, should have been provided under the Essential Health Insurance Plan.[19] Psychotropic medications accounted for 10.3% of total out-of-pocket pharmaceutical spending in Peru’s private retail sector between 2018 and 2023, making them the fourth-largest therapeutic category after anti-infectives, pain and palliative care, and cardiovascular treatments.[20] The most commonly consumed psychotropic medications included clonazepam, sertraline, and fluoxetine. These figures illustrate both a high demand for such drugs and a systemic failure to ensure their availability and affordability through guaranteed public mechanisms.

These systemic deficits have also fueled the widespread practice of self-medication. Self-medication is common throughout Peru, crossing regions and socioeconomic groups. National data show that nearly 76% of people report purchasing medication without a prescription, and a 2019 market survey found that only 6% of Peruvians claimed not to self-medicate at all.[21] The prevalence is especially high in low-income populations and in the Andes and Amazon regions, where barriers to accessing public health services are greatest. In Lima, studies reveal that self-medication is more frequent in low-income districts (66.7%) compared to wealthier areas (40.6%). During the COVID-19 pandemic, this trend became even more pronounced.[22]

Several factors explain the persistence of self-medication in Peru, including limited access to affordable public health, weak pharmaceutical regulation enforcement, and cultural reliance on family advice for minor illnesses. Pharmacies often sell restricted medications without prescriptions, with pharmacists recommending drugs based on informal consultations. Although Peruvian law criminalizes the sale of psychotropic drugs without a prescription (Law No. 30681), enforcement is weak.[23] A study found that not requesting a prescription is the strongest predictor of unsafe self-medication.[24] These issues, driven by poor access to public care and commercial interests, disproportionately affect low-income users and may lead to unsafe medication practices.

Taken together, these dynamics reveal a fragmented and inequitable mental health system in which pharmacies have become default providers—particularly for those facing economic and geographic barriers to formal care—reflecting a mismatch between supply and need that drives reliance on market-based pathways to care.

Pharmacy chains and market dominance

Pharmacies play a critical role as frontline health care providers in low- and middle-income countries, where formal health systems face chronic underfunding, workforce shortages, and limited infrastructure. However, this prominent role has raised concerns regarding the consistency and quality of the service they provide. Studies have documented problematic issues, including inadequate training among their staff, weak or uneven regulatory enforcement, and the routine sale of prescription-only medications without authorization.[25]

Private pharmacies have a broad presence across Peru. As of 2024, there were 23,280 registered establishments, with the majority located in urban areas.[26] Due to their widespread availability, relatively low cost, and perceived convenience, they often serve as initial contact points for health care advice and medications, particularly where formal health services are scarce or difficult to access.[27]

The Peruvian retail pharmacy market is notably concentrated, dominated by two major chains—InkaFarma and Mifarma—both owned by InRetail Pharma since 2018. Although independent establishments constitute 85.8% of all private pharmacies, chain pharmacies control approximately 79.2% of total pharmaceutical retail sales, with InkaFarma and Mifarma alone making up 57.3% of chain-affiliated establishments.[28] This level of market consolidation grants these chains considerable influence over medication pricing, availability, and retail practices. National household survey data indicate that pharmacies are the most common point of care (14.7%) among Peruvians who experience health problems, surpassing public health facilities and private clinics.[29]

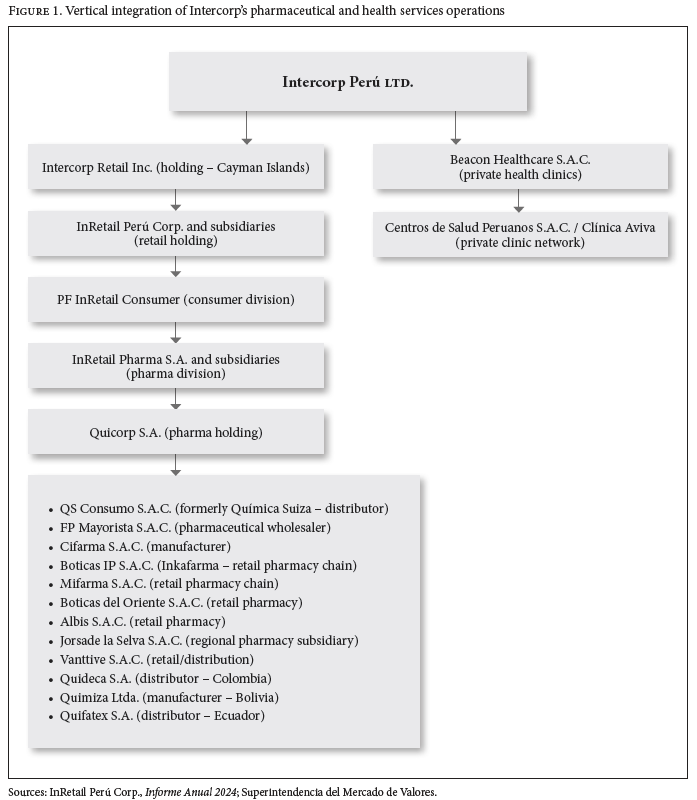

Peru’s pharmaceutical sector has seen major consolidation in recent years, raising concerns about competition and consumer access. In 2018, InRetail Pharma, a subsidiary of Intercorp Perú, acquired Quicorp, which owned key pharmacy chains, including Mifarma, Boticas BTL, Fasa, and Arcángel. At the time, Peru lacked a regulatory framework for mergers. This deal unified over 80% of the pharmacy chain market under one group, reducing competition and creating a vertically integrated supply chain—from manufacturing (Cifarma) to distribution (QS Consumo, FP Mayorista), and retail (Inkafarma, Mifarma) (see Figure 1). This integration disadvantages independent pharmacies, limiting their access to distribution and preventing them from negotiating better prices. Following the merger, prices for essential medicines increased, raising concerns that market dominance may be driving up costs for consumers.[30]

Although further data would help clarify the scope of vertical integration in psychotropic medication production specifically, the existing structure suggests that pharmacy chains exercise significant control over which medications are stocked and prioritized. This influence is particularly concerning in the mental health field, where the dominance of branded or private-label medications can restrict access to affordable generics and shape treatment pathways according to commercial incentives rather than clinical need or rational use.

This concentration of power and vertical integration across the pharmaceutical supply chain generates structural dependencies that can distort public health priorities, undermining transparency, reducing accountability, and reinforcing a system in which corporate interests take precedence over equitable access to essential medications.

Institutional corruption in pharmaceutical retail

Corruption in health systems encompasses a wide range of behaviors that undermine public trust, distort service delivery, and compromise patient well-being. These include not only illegal acts but also more systemic and subtle forms of distortion. As Nahitun Naher et al. and Eleanor Hutchinson et al. have shown, corruption in health care often manifests as multifaceted institutional failures, such as informal payments, the manipulation of procurement processes, regulatory capture, and entrenched conflicts of interest.[31]

This paper adopts Lawrence Lessig’s conception of institutional corruption as a guiding framework.[32] According to Lessig, institutional corruption refers to systemic and legal influences that, while not necessarily involving illegality, “weaken the effectiveness of an institution, especially by weakening the public’s trust in that institution.” Such influences tend to create dependencies—financial, political, or structural—that diverge institutional behavior from its public purpose. Unlike classic corruption, which typically involves personal enrichment or unlawful conduct, institutional corruption operates through legal but ethically problematic channels that erode the integrity of institutions over time.

This distinction is especially salient in Peru’s health sector, where decades of pro-market reforms have prioritized private sector expansion and deregulation. While these reforms were intended to enhance supply and efficiency, they often outpaced the development of robust oversight mechanisms. As a result, institutional arrangements in the pharmaceutical sector have become increasingly shaped by commercial dependencies rather than public health goals. This creates fertile ground for institutional corruption: legally permissible practices that subvert the public interest, distort the delivery of care, and weaken rights-based oversight.

In this context, the role of pharmacy chains illustrates how market-driven structures can enable systemic exploitation. These practices can be grouped into five interrelated areas: price distortion, anticompetitive collusion, sales without prescription, conflicts of interest in service provision, and regulatory capture and lobbying. Each of these reflects a form of institutional distortion that, while not always illegal, undermines the right to health and weakens the state’s capacity to ensure equitable access to essential care.

Price distortion

In Peru’s highly concentrated pharmaceutical retail sector, pharmacy chains have adopted pricing strategies that, while permissible under the country’s prevailing free-market framework, directly undermine the affordability of and equitable access to psychotropic medications. Dominant pharmacy chains such as InkaFarma and Mifarma routinely promote their own private-label psychotropic drugs as default options, a pattern reflected in staff recommendations that favor these products over lower-cost generics. These strategies are further reinforced by systematically withholding cheaper alternatives from store shelves. Even when generics are available, their prices are often set only marginally below those of branded or private-label products, limiting their appeal to cost-sensitive consumers and reinforcing the dominance of high-margin items.

A 2023 field investigation by Salud con Lupa across 31 pharmacies in Lima, the capital city, and Chiclayo, one of the most populous urban centers in northern Peru, found that in most cases, staff offered only branded versions of essential psychotropics despite the existence of cheaper generics.[33] For example, clomipramine (sold as Praminex in private pharmacies) was priced at approximately PEN 314 (approximately US$84), about one-third of the minimum wage at the time (PEN 1,025), while the generic version—if available in public pharmacies—would cost up to 15 times less. This pattern is not isolated: according to the Ministry of Health, several essential psychotropic medications are either unavailable in private chains or offered only as branded products, affecting both affordability and access.[34]

National data on the private market for antidepressants reveal similar distortions. Using price data from the Peruvian Observatory of Pharmaceutical Products, Javier Llamoza et al. documented multiple pricing anomalies in psychotropic medications sold in private pharmacies.[35] In several cases, the prices of branded generics and those sold under their international nonproprietary name (INN) were nearly identical, offering little real cost advantage. More strikingly, several branded generics were found to be as expensive—or even more expensive—than the innovator products themselves. For instance, in the case of fluoxetine, Genfar’s branded generic for Prozac had a higher unit price than the original Prozac from Eli Lilly, while the INN-labeled version offered only a marginal difference. Consumers with limited financial means may mistakenly believe they are purchasing a lower-cost option when, in fact, the price difference is minimal or nonexistent.

Similar sales patterns have been documented in other therapeutic areas. A 2024 study by the Instituto de Defensa Legal found that InRetail-owned pharmacies systematically promoted their own branded products over lower-priced generics, with price differences of up to 18 times depending on the location.[36]

The National Association of Pharmacy Chains, which represents major retail chains, has argued that the availability of generic psychotropic medications depends on the laboratories that manufacture or import them.[37] However, many pharmacy chains are vertically integrated or maintain close affiliations with manufacturers and distributors, giving them significant influence over what is stocked and offered.

To contextualize these dynamics with quantitative evidence, future research and policy analysis should systematically monitor retail pricing and availability across time.

Anticompetitive collusion

Dominant pharmacy chains in Peru have not only shaped market dynamics through pricing strategies but have also engaged in overt anticompetitive practices that restrict consumer choice and reinforce corporate control.

A landmark investigation by the National Institute for the Defense of Competition and Protection of Intellectual Property (Indecopi) revealed in 2016 that five major pharmacy chains—including InkaFarma and Mifarma—colluded to fix the prices of 36 essential medicines, including widely used psychotropics such as alprazolam and fluoxetine.[38] Internal communications uncovered during the investigation detailed coordinated pricing strategies and agreements to maintain inflated prices across competing retail outlets.[39]

The 2016 ruling imposed fines exceeding PEN 9 million (approximately US$2.6 million) and revealed serious shortcomings in the oversight of Peru’s pharmaceutical market. However, the structural incentives that enabled collusion remain largely unaddressed. Subsequent mergers and acquisitions have further consolidated the dominance of major pharmacy groups, while vertical integration in Peru’s pharmaceutical sector continues to create favorable conditions for price coordination and supply manipulation.[40]

For example, in July 2024, Indecopi launched a new administrative sanctioning procedure against 15 pharmaceutical companies and five individuals for alleged collusion in 23 public procurement processes between 2006 and 2020, involving medicines purchased by the national government.[41] While the companies under investigation are not directly linked to retail pharmacy chains, the case underscores the broader systemic risks posed by market concentration and weak institutional safeguards across the pharmaceutical supply chain. It also highlights the vulnerability of state procurement processes to manipulation by dominant market actors.

Anticompetitive practices among retail chains restrict access to affordable treatment and contribute to sustained price increases, a situation particularly harmful in the case of psychotropic medications, which are often prescribed for long-term use.

Sales without prescription

Although psychotropic drugs are legally restricted to prescription-only sales, they are also commonly used without a prescription due to weak regulatory enforcement and the high unmet demand for mental health treatment. In Peru, the unauthorized sale of controlled substances, including psychotropic drugs, is a criminal offense under Law No. 30681, which amended the Penal Code to penalize such practices.

In 2012, the Ministry of Health reported that approximately 25% of private pharmacies were selling controlled substances without requiring a medical prescription, despite legal prohibitions and the known risks of dependency and overdose.[42] Subsequent field inspections have continued to uncover repeated violations, including the unsupervised sale of medications such as alprazolam, diazepam, and fluoxetine, as well as the absence of licensed pharmacists during operating hours.[43]

A 2019 hospital-based study in Lima found that 45.5% of service users had used benzodiazepines without a valid prescription, and among them, nearly 63% met the criteria for treatment due to substance abuse, compared to just 27% among those with a prescription.[44] Other local studies have shown that factors like perceived symptom severity, social influence, and convenience drive the demand for anxiolytics without medical oversight.[45]

The widespread sale of psychotropic medications without prescriptions reflects again commercial practices that exploit gaps in mental health service provision. In contexts where pharmacies serve as the primary point of access, these practices normalize unsafe dispensing and contribute to patterns of inappropriate medication use.

Conflicts of interest in service provision

In Peru, pharmacy chains have increasingly blurred the lines between retail and care, sometimes functioning not only as vendors but also as informal or emerging providers of mental health services. This convergence—selling medications while also facilitating or influencing their prescription—can create conflicts of interest, particularly in a market where psychotropic drugs are highly profitable and regulatory enforcement remains limited.

One expression of this convergence is the emergence of corporate-run telehealth platforms that offer remote prescriptions. Marketed as teleconsultations, these services operate with minimal oversight and primarily serve to direct consumers toward affiliated retail outlets. For example, Aliviamed—an online platform linked to major pharmacy chains—offers virtual consultations that can result in prescriptions for psychotropic medications, which are then filled through the same corporate network.[46] This example points to a wider regional trend: telehealth has expanded faster than regulatory capacity, raising similar concerns about oversight and accountability.[47]

These platforms emerge in a context where pharmacies already provide informal guidance about medication, often from staff with no formal clinical training. Research on pharmacy practice in Peru has long noted the absence of structured pharmaceutical care and the limited involvement of qualified professionals in patient counseling.[48] Staff frequently recommend medications, interpret symptoms, and advise on treatment choices in ways that go beyond their technical remit.[49] Although regulatory standards exist, such as requirements for qualified personnel and restrictions on prescription-only medicines, these interactions are rarely subject to systematic oversight. Moreover, investigations indicate that staff at major pharmacy chains routinely promote specific products—particularly high-margin private-label brands—regardless of clinical guidelines or individual user needs.[50] These commercial strategies, typically centralized and performance-driven, can facilitate inappropriate treatment, dependency, or overuse, especially when users receive guidance from nonprofessionals. Similar commercial pressures affect licensed professionals, whose ethical and professional judgment can be compromised when remuneration or sales incentives influence prescribing or dispensing decisions.

While pharmacy chains often function as the de facto front door to the health system in underserved areas, accessibility alone does not fulfill the right to health. The right to health also requires quality, safety, continuity of care, and access to reliable information—conditions that commercial dispensing models cannot guarantee in the absence of adequate oversight. Without effective regulation, this model risks normalizing a system in which commercial actors shape mental health care delivery without accountability.

Regulatory capture and lobbying

Pharmacy chains in Peru have not only expanded their market power but have also increasingly influenced the legal and regulatory frameworks meant to oversee them. Their ability to delay, dilute, or shape public health regulations reflects broader dynamics of regulatory capture—where private actors exert sustained influence over public institutions, steering policy and oversight mechanisms to align with commercial interests. This has been especially evident in debates surrounding access to generic drugs and the role of pharmacies in health care provision.

A notable example is the protracted and politically divisive process leading to Law No. 32033, passed in May 2024, which reinstated a requirement for pharmacies to stock a minimum percentage of essential generics.[51] The law traces back to Emergency Decree No. 007–2019, which mandated private pharmacies to carry 40 essential generic drugs identified by their INNs. Although supported by the Ministry of Health, the decree faced strong opposition from private pharmacies and industry groups.[52] As the obligation neared its expiry in early 2024, the government allowed it to lapse amid lobbying from interest groups.[53] Following public pressure from health advocacy organizations, the executive branch issued Emergency Decree No. 005–2024, restoring the mandate but requiring pharmacies to offer 30% of their total generic product list, without specifying which drugs must be stocked—thereby allowing broad discretion.[54]

Though Law No. 32033 reaffirmed these regulatory provisions on the stocking of essential generics, it has been criticized by advocacy organizations for not addressing structural issues such as market concentration or mandatory generic lists.[55] Pharmacies remain free to choose which medications to offer, potentially favoring high-turnover or more profitable items, and the law exempts small independent pharmacies. The latter exemption has been questioned as politically motivated, allegedly benefiting family members of congressional sponsors.[56]

Another key case is Indecopi’s 2024 ruling overturning a Ministry of Health ban on in-pharmacy consultations and prescriptions.[57] The challenge, brought by three retail chains, including Mifarma, argued that the ban lacked a legal basis and violated the principle of free enterprise. The complaint was initially denied but later upheld on appeal. Industry groups welcomed the decision as removing barriers to care, while professional associations warned that it would undermine clinical standards and create conflicts of interest.[58] Later that year, Law No. 32033 reintroduced the restrictions, explicitly prohibiting in-person consultations, diagnostic tests, and sample collection within pharmacy premises. However, it did not regulate virtual services, leaving a gap that may allow pharmacy-affiliated telehealth platforms to continue issuing prescriptions remotely.

Most recently, Law No. 32319, adopted in April 2025, introduced changes to the regulation of bioequivalence and the substitution of brand-name drugs with generics.[59] The reform reduced the Ministry of Health’s oversight role and shifted greater responsibility to prescribing physicians, who may authorize substitutions at their discretion. While proponents argue that this expands access, critics contend that it weakens pharmacological safeguards and opens the door to commercial rather than clinical considerations.[60] The law has been criticized for favoring the pharmaceutical industry by introducing partial obligations, allowing selective compliance, and avoiding more robust reforms that would curb the dominance of corporate chains or guarantee the availability of essential medicines.

Human rights implications

Applying the international human rights framework, including the right to health as enshrined in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and CRPD, provides a vital perspective for analyzing pharmacy practices in Peru. These frameworks emphasize that health is not a commodity but a fundamental right to which everyone is entitled without discrimination. Viewed through this lens, Peru’s mental health care system reveals gaps in service provision as well as a broader failure to regulate commercial practices that undermine equitable access and accountability.

Under article 12 of the ICESCR, states are obliged to ensure the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. This is elaborated through the AAAQ framework: availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality.[61] In Peru, dominant pharmacy chains play a central role in determining the availability and accessibility of psychotropic medications, often to the detriment of equitable access. Branded and private-label drugs are prioritized over affordable generics, while unregulated pricing and nonprescription sales erode both affordability and safety. The sale of psychotropic medications without prescriptions and the use of untrained staff in retail chains further compromises the quality of care. Taken together, these practices undermine the AAAQ standards and illustrate the risks of deflecting core health functions to private actors with limited oversight, in violation of the state’s obligation to ensure the right to health. Intersectional barriers—based on factors such as location, gender, disability, or Indigenous identity—further entrench these inequities, deepening disparities in access to information, treatment, and support.

While the state is the primary duty bearer, international human rights law also imposes responsibilities on private actors. The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights establish that companies must avoid causing or contributing to human rights abuses and take appropriate action to prevent, mitigate, and remedy adverse impacts when they occur. In Peru, vertically integrated pharmacy conglomerates influence not only medication pricing but also prescription practices and regulatory decisions, effectively shaping treatment pathways. This convergence of commercial, clinical, and regulatory roles intensifies conflicts of interest and weakens safeguards for equitable care, highlighting the urgent need for stronger state oversight. These dynamics gradually divert public institutions from their intended purpose—not through isolated misconduct but through sustained commercial influence that reshapes regulatory priorities and public norms. Applying the United Nations Guiding Principles requires the state to fulfill its duty to protect, companies to respect human rights, and both to ensure access to effective remedies for those affected.

Transparency and accountability—cornerstones of the right to health—require that public health decisions, including those related to pricing, stocking, and prescribing, be subject to clear rules, public scrutiny, and effective grievance mechanisms. Yet in Peru, dominant pharmacy chains obscure pricing structures and restrict access to affordable generics, while expanding their influence through opaque lobbying and regulatory capture. These dynamics undermine public trust and compromise both affordability and transparency. To fulfill their obligations, Peruvian authorities must strengthen independent oversight, promote transparency in pharmaceutical governance, and ensure that regulatory frameworks are equipped to prevent and remedy conduct incompatible with the right to health.

The CRPD marks a paradigm shift in mental health provision, calling for a move away from coercive, biomedical-dominated models and toward community-based, rights-oriented approaches.[62] As the Special Rapporteur on the right to health has emphasized, the overmedicalization of mental distress, particularly through excessive reliance on psychotropic medication, can itself constitute a human rights violation when it results from structural coercion, lack of informed consent, or the absence of alternatives.[63] In Peru, the commercial interests of pharmacy chains intersect with the inadequacies of the public system to create a “pharmaceuticalized model” of mental health care by default. In practice, this results in a form of structural coercion: medication becomes the only available response to distress, though not necessarily the most appropriate. The absence of psychosocial alternatives and the commodification of care risk entrenching a system where medicalization replaces support and profit dictates care. Upholding CRPD obligations demands not only investment in public services but also a profound rethinking of medicalization, robust regulation of pharmaceutical practice, and a transition toward user-led, community-centered mental health supports.

Lastly, both the ICESCR and CRPD frameworks emphasize participation as a central pillar of health governance. This entails the meaningful involvement of affected populations—particularly those historically marginalized—in shaping laws, policies, and services. Yet in Peru, persons with psychosocial disabilities and service users remain largely excluded from regulatory and legislative processes.[64] Global mental health systems remain dominated by top-down approaches that concentrate power among biomedical and corporate actors, often at the expense of local knowledge, lived experience, and community-led alternatives.[65] Shifting toward participatory governance is essential to rebuild trust, correct power asymmetries, and ensure that reforms reflect the needs and rights of those most affected. Ensuring participation in oversight and grievance mechanisms would help realize these principles in practice and strengthen accountability toward those most affected.

Rethinking pharmacy power in mental health care

The systemic problems explored in this paper show that market-driven practices cannot be addressed in isolation. These practices reflect longstanding governance failures and demand structural changes in health system design and pharmaceutical regulation. Rights-based reforms must focus on restoring the public purpose of health institutions and ensuring that private actors operate within clearly defined legal and ethical boundaries.

While health advocates and pharmacy chains often diverge, there is broad recognition that the growing role of private pharmacies in mental health care stems from chronic underfunding and the limited reach of public mental health infrastructure. The widespread unavailability of timely, affordable care at the community level and the lack of psychotropic medications in state-run pharmacies leave many with no option but to turn to retail chains. This is compounded by a deeply embedded culture of medicalization that frames pharmacological treatment as the default response to distress.[66] Addressing these structural drivers requires both expanding public capacity and challenging embedded narratives about mental health and care.

While structural reform will take time, short-term policy measures can improve access to psychotropic medications in public facilities. These measures should avoid reinforcing a medication-centric model while ensuring safe and equitable access for those who need it, as part of broader care options. Recommended actions include expanding the Single National List of Essential Medicines through transparent, participatory processes; strengthening procurement; and promoting electronic prescriptions to inform public supply systems.[67] These efforts must be accompanied by strong public information campaigns to direct users toward public services, encourage the safe and informed use of psychotropic medication, and counter misconceptions about generics. Messaging should promote awareness of psychosocial alternatives and challenge the idea that medication is the only or default response to distress. Tools such as the Ministry of Health’s Medicine Price Observatory, which promote price transparency, should be strengthened and more widely used.[68]

Despite the central role of private pharmacies, Peru’s regulatory framework remains weak and poorly enforced. The Constitution enshrines free-market principles and limits state intervention in pricing, constraining efforts to curb exploitative practices. Since the 2021 introduction of Law No. 31112 establishing a merger control procedure, Indecopi has received 80 merger authorization requests, of which 66 have been approved, six have been withdrawn, four remain under evaluation, three are at the admissibility stage, and only one has been denied.[69] The Ministry of Health also faces chronic capacity constraints and high political turnover, with 18 different ministers serving between 2016 and 2025, averaging less than six months each. This instability undermines regulatory continuity and weakens enforcement. For instance, there has been little independent evaluation of recent emergency decrees or Law No. 32033 and their impact on access to generic medicines. Anecdotal evidence and comparative experience suggest that these measures may fall short in practice.[70]

To begin addressing current regulatory shortcomings—and in parallel with efforts to improve access to medications in state-run facilities—a set of short- and medium-term policy options could be considered. These may include:

- mandating clear price disclosures and the publication of real-time data on generic availability;

- accelerating the approval and market entry of high-quality, interchangeable generic psychotropic medications to increase competition and affordability;

- strengthening conflict-of-interest regulations and prohibiting sales quotas for pharmacy staff;

- restricting vertical integration between retail chains and pharmaceutical manufacturers;

- banning virtual consultations that are directly linked to medication dispensing;

- strictly enforcing prescription requirements for controlled medications, particularly psychotropics, and strengthening audits and supervision; and

- enforcing existing obligations to display the INN alongside brand names, and establishing standardized substitution protocols to improve transparency and promote the rational use of medicines.

These proposals are not intended to be exhaustive or prescriptive. Instead, they reflect potential areas of intervention where reforms could contribute to greater transparency, equity, and accountability in pharmaceutical governance, while reducing systemic incentives that perpetuate overmedicalization and market-driven distortions in mental health care.

To ensure the effectiveness of such measures, regulatory authorities should also conduct regular audits, impose meaningful sanctions for noncompliance, and ensure that enforcement mechanisms are shielded from political and commercial pressure. These efforts should be supported by sustained investments in training for regulatory agency staff, digital infrastructure, and improved coordination between regulatory agencies and public health providers.

Conclusion

This paper has examined the convergence of systemic neglect, weak regulation, and market concentration in Peru’s mental health care system. Despite reform efforts, chronic shortages of psychotropic medications in public facilities, combined with the underdevelopment of community-based services, have driven large segments of the population toward self-medication and dependence on private pharmacies. Within this vacuum, vertically integrated pharmacy chains have expanded their control over the supply, pricing, and even prescription of medications, often prioritizing commercial gain over public health. These dynamics expose deep regulatory and institutional gaps. In the absence of independent evaluation, transparent monitoring, and effective enforcement, recent legal reforms risk falling short and may ultimately entrench, rather than remedy, existing inequalities.

Responding to these challenges requires a structural shift in how mental health care is delivered and how pharmaceutical markets are governed. In Peru, restoring public confidence and rebalancing the influence of private pharmacy chains must begin with sustained public investment—not only to ensure the availability of affordable psychotropic medications through public channels but also to advance non-medicalized, community-based approaches to care that center user needs and reduce reliance on pharmacological treatment. At the same time, short- and medium-term regulatory reforms are needed to strengthen safeguards against conflicts of interest in prescribing and dispensing practices, promote transparency, and ensure that regulatory institutions are protected from lobbying and undue commercial influence. Further research is needed to explore how market concentration and pharmaceutical governance affect the realization of the right to mental health in Peru and comparable settings.

Ultimately, rights-based regulation involves more than legal enactments. It requires strong public institutions, independent oversight, and the political will to curb entrenched market power. Where public agencies are shaped by sustained commercial influence—whether through lobbying, conflicts of interest, or regulatory inertia—their capacity to serve the public good is systematically weakened. Building a transparent, accountable, and equitable mental health system demands both structural investment and targeted regulatory action. But neither will be effective without a clear commitment to prioritizing human rights and reorienting institutions toward their core public responsibilities.

Alberto Vásquez Encalada is a mad/disability rights activist and co-director of Mad Thinking, Geneva, Switzerland.

Please address correspondence to the author. Email: avasqueze@gmail.com.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2025 Vásquez Encalada. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

[1] World Bank, Peru: Systematic Country Diagnostic Update (2022)

[2] Defensoría del Pueblo, Informe defensorial No. 180: Derecho a la salud mental (2018).

[3] Pan American Health Organization, Avances y desafíos de la reforma de salud mental en el Perú en el último decenio (2023).

[4] J. K. Cabanillas-Tejada, H. L. Allpas-Gómez, J. D. Brito-Nuñez, and C. R. Mejia, “Automedicación y riesgo de abuso con benzodiacepinas en pacientes adultos Lima-Perú, 2019,” Revista Chilena de Neuro-Psiquiatría 60/3 (2022).

[5] J. B. Pari-Olarte, P.A. Cuba-García, J. S. Almeida-Galindo, et al., “Factores asociados con la automedicación no responsable en el Perú,” Revista del Cuerpo Médico Hospital Nacional Almanzor Aguinaga Asenjo 14/1 (2021).

[6] Defensoría del Pueblo (see note 2).

[7] H. Castillo-Martell and Y. Cutipé-Cárdenas, “Implementación, resultados iniciales y sostenibilidad de la reforma de servicios de salud mental en el Perú, 2013–2018,” Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública 36/2 (2019); Pan American Health Organization (see note 3).

[8] Ministerio de Salud, “Minsa fortalece la atención en salud mental con 291 Centros de Salud Mental Comunitaria” (May 6, 2025), https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minsa/noticias/1162506-minsa-fortalece-la-atencion-en-salud-mental-con-291-centros-de-salud-mental-comunitaria.

[9] Pan American Health Organization (see note 3).

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.; Defensoría del Pueblo (see note 2); J. A. Claux, F. Diez Canseco, P. Gamarra P, and P. Smith Castro, Servicios e intervenciones en situaciones de crisis o emergencias en salud mental en Lima: Estudio cualitativo (Sociedad y Discapacidad, 2025).

[13] Defensoría del Pueblo (see note 2); A. Tovar and R. Romero, “Los hospitales psiquiátricos y los medicamentos que no llegan,” Salud con Lupa (June 18, 2023), https://saludconlupa.com/salud-mental/los-hospitales-psiquiatricos-pagan-precios-mas-altos-por-las-medicinas-que-compran-en-forma-directa/.

[14] Tovar and Romero (see note 13).

[15] Ministerio de Salud, Resolución Ministerial No. 686-2024-MINSA, Plan Nacional de Fortalecimiento de Servicios de Salud Mental Comunitaria 2024–2028 (October 15, 2024), https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minsa/normas-legales/6094628-686-2024-minsa.

[16] J. Llamoza, J. Risof Solís, and S. E. Zevallos Bustamante, Estado situacional de la depresión en el Perú: Cómo se comporta la depresión en el país, a cuántos afecta y con qué contamos para combatirla (Gobierna Consultores, 2022).

[17] Ibid.

[18] A. M. Osorio, R. M. M. Colán, J. A. Rosales, and N. M. Pinedo, Gasto de bolsillo en salud y medicamentos, periodo 2012–2019 (Ministerio de Salud, 2021).

[19] M. Crisante Núñez, Informe del gasto de bolsillo en productos farmacéuticos en farmacias y boticas privadas del sector retail. Periodo 01/2018–12/2023 (Ministerio de Salud, 2024)

[20] Ibid.

[21] M. G. Pinedo Bardales, Factores asociados a la compra de medicamentos sin receta médica según las macrorregiones de Perú en 2016, master’s thesis (Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, 2023), https://repositorio.upch.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12866/13895; Kantar, “6 de cada 100 peruanos no se automedica” (April 24, 2019), https://www.kantarworldpanel.com/pe/Noticias/6-de-cada-100-peruanos-no-se-automedica.

[22] P. J. Navarrete-Mejía, J. C. Velasco-Guerrero, and L. Loro-Chero, “Automedicación en época de pandemia: Covid-19,” Revista del Cuerpo Médico Hospital Nacional Almanzor Aguinaga Asenjo 13/4 (2020).

[23] Peru, Ley No. 30681, Ley que regula el uso medicinal y terapéutico del cannabis y sus derivados (2017).

[24] Pari-Olarte et al. (see note 5).

[25] F. Smith, “The Quality of Private Pharmacy Services in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review,” Pharmacy World and Sciience 31/3 (2009); Z. U. D. Babar, “Ten Recommendations to Improve Pharmacy Practice in Low- and Middle-Income Countries,” Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice 14/1 (2021).

[26] Ministerio de Salud, Dirección General de Medicamentos, Insumos y Drogas, Boletín de Establecimientos Farmacéuticos 5/8 (2024).

[27] Videnza Consultores, Situación actual del sistema de salud peruano (AIS, 2024); E. Vodicka, D. A. Antiporta, Y. Yshii, et al., “Patient Acceptability of and Readiness-to-Pay for Pharmacy-Based Health Membership Plans to Improve Hypertension Outcomes in Lima, Peru,” Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 13/3 (2017).

[28] Ministerio de Salud (see note 26).

[29] Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Condiciones de vida en el Perú: Enero-Febrero-Marzo 2025 (2025), https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/8249170/6886713-condiciones-de-vida-en-el-peru-enero-febrero-marzo-2023.pdf?v=1750688633.

[30] D. L. Balbin, A. E. Fontela, B. Juarez, and O. E. Zegarra, La concentración en el sector farmacéutico peruano y su impacto económico, master’s thesis (ESAN University, 2020), https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12640/2056.

[31] N. Naher, R. Hoque, M. S. Hassan, et al., “The Influence of Corruption and Governance in the Delivery of Frontline Health Care Services in the Public Sector: A Scoping Review of Current and Future Prospects in Low and Middle-Income Countries of South and South-East Asia,” BMC Public Health 20/880 (2020); E. Hutchinson, D. Balabanova, and M. McKee, “We Need to Talk About Corruption in Health Systems,” International Journal of Health Policy and Management 8/4 (2019).

[32] L. Lessig, “‘Institutional Corruption’ Defined,” Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 41/3 (2013).

[33] A. Tovar and R. Romero, “Precios altos y sin opción de genéricos: La oferta de medicinas de salud mental en boticas privadas,” Salud con Lupa (May 28, 2023), https://saludconlupa.com/salud-mental/precios-altos-y-sin-opcion-de-genericos-la-oferta-de-medicinas-de-salud-mental-en-boticas-privadas/.

[34] Crisante Núñez (see note 19)

[35] Llamoza et al (see note 16).

[36] J. Llamoza, Prácticas comerciales en boticas del grupo InRetail en la venta de un grupo de medicamentos (Instituto de Defensa Legal, 2024).

[37] Tovar and Romero (see note 33).

[38] Instituto Nacional de Defensa de la Competencia y de la Protección de la Propiedad Intelectual, Resolución No. 078-2016/CLC-INDECOPI, Case File No. 008-2010/CLC (October 12, 2016).

[39] V. F. Burgos Zavaleta and M. L. Burgos Jaeger, “Un análisis al monopolio del mercado farmacéutico en Perú,” Humanidades y Tecnologia (FINOM) 43/1 (2023).

[40] Balbin et al (see note 30).

[41] Instituto Nacional de Defensa de la Competencia y de la Protección de la Propiedad Intelectual, “El Indecopi inicia procedimiento sancionador contra 15 empresas por presunta colusión en el mercado de medicamentos” (July 16, 2024), https://www.gob.pe/institucion/indecopi/noticias/989523-el-indecopi-inicia-procedimiento-sancionador-contra-15-empresas-por-presunta-colusion-en-el-mercado-de-medicamentos/.

[42] Ministerio de Salud, “El 25% de farmacias y boticas privadas vende ansiolíticos y antidepresivos sin receta médica” (October 11, 2012), https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minsa/noticias/67434-el-25-de-farmacias-y-boticas-privadas-vende-ansioliticos-y-antidepresivos-sin-receta-medica.

[43] Ministerio de Salud, “Intervienen farmacias y boticas que vendían medicamentos psicotrópicos sin exigir receta” (April 2, 2018), https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minsa/noticias/66190-intervienen-farmacias-y-boticas-que-vendian-medicamentos-psicotropicos-sin-exigir-receta.

[44] Cabanillas-Tejada et al. (see note 4).

[45] J. C. Ramirez Choquehuanca and A. S. Torres Mamani, Factores influyentes en la automedicación con ansiolíticos en personas que acuden a oficinas farmacéuticas de la ciudad de Puno, bachelor’s thesis (Universidad María Auxiliadora, 2022), https://repositorio.uma.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12970/1958.

[46] Aliviamed, https://www.aliviamed.pe/.

[47] G. Camacho-Leon, M. Faytong-Haro, K. Carrera, et al., “A Narrative Review of Telemedicine in Latin America During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Healthcare (Basel) 10/8 (2022).

[48] A. Alvarez-Risco and J. W. van Mil, “Pharmaceutical Care in Community Pharmacies: Practice and Research in Peru,” Annals of Pharmacotherapy 41/12 (2007).

[49] Pari-Olarte et al (see note 5).

[50] Tovar and Romero (see note 33).

[51] Peru, Ley No. 32033, Ley que garantiza y promueve el acceso y uso a los medicamentos genéricos en Denominación Común Internacional (DCI) y fortalece la regulación de los productos farmacéuticos y dispositivos médicos en beneficio de los pacientes y usuarios (2024).

[52] Asociación Nacional de Cadenas de Boticas, “Advierte informe de APOYO Consultoría: Iniciativas del Congreso para regular venta de genéricos no generarán ahorros a la población y reducirían la oferta y acceso a los medicamentos” (April, 29, 2024), https://anacab.pe/salud-publica/advierte-informe-de-apoyo-consultoria-iniciativas-del-congreso-para-regular-venta-de-genericos-no-generaran-ahorros-a-la-poblacion-y-reducirian-la-oferta-y-acceso-a-los-medicamentosiniciativas-del-co/.

[53] See, for example, Colegio Químico Farmacéutico del Perú, “El Colegio Químico Farmacéutico del Perú solicitó al MINSA la no prórroga y derogación del DU No 007-2019” (December 29, 2023), https://cqfp.pe/el-colegio-quimico-farmaceutico-del-peru-solicito-al-minsa-la-no-prorroga-del-du-n007-2019/.

[54] Peru, Decreto de Urgencia No. 005-2024, Decreto de Urgencia que dicta medidas extraordinarias en materia económica y financiera para garantizar el acceso a medicamentos genéricos a la población (2024).

[55] “¿Cuáles son las trampas de la nueva ley de medicamentos genéricos?,” Salud con Lupa (May 22, 2024), https://saludconlupa.com/noticias/cuales-son-las-trampas-de-la-nueva-ley-de-medicamentos-genericos/.

[56] Federación de Periodistas del Perú, “Fujimorismo promueve ley de genéricos que favorece a hijos de congresistas” (March 14, 2024), https://fpp.org.pe/fujimorismo-promueve-ley-de-genericos-que-favorece-a-hijos-de-congresistas/.

[57] Instituto Nacional de Defensa de la Competencia y de la Protección de la Propiedad Intelectual, Resolución 0102-2024/SEL-INDECOPI (January 19, 2024).

[58] Colegio Médico del Perú, “CMP rechaza resolución de Indecopi que permite comercializar víveres en establecimientos farmacéuticos” (March 6, 2024), https://www.cmp.org.pe/cmp-rechaza-resolucion-de-indecopi-que-permite-comercializar-viveres-en-establecimientos-farmaceuticos/.

[59] Peru, Ley No. 32319, Ley que establece medidas para facilitar el acceso a medicamentos y productos biológicos registrados en países de alta vigilancia sanitaria destinados al tratamiento de enfermedades raras, huérfanas, cáncer y demás enfermedades (2025).

[60] C. Torres Tutiven, “Óscar Ugarte: Ley 32319 pone en riesgo la salud pública,” Canal N (May 2, 2025), https://canaln.pe/actualidad/oscar-ugarte-ley-32319-pone-riesgo-salud-publica-n483067; “Medicamentos sin garantías: Lo qué hay detrás del proyecto de ley que debilita a la Digemid,” Salud con Lupa (December 16, 2024), https://saludconlupa.com/noticias/medicamentos-sin-garantias-lo-que-hay-detras-del-proyecto-de-ley-que-debilita-a-la-digemid/.

[61] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000).

[62] World Health Organization and the United Nations, Mental Health, Human Rights and Legislation: Guidance and Practice (World Health Organization, 2023).

[63] United Nations General Assembly, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health, UN Doc. A/72/137 (2017); Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health, UN Doc. A/HRC/44/48 (2020).

[64] Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Concluding Observations: Peru, UN Doc. CRPD/C/PER/CO/2-3 (2023).

[65] United Nations General Assembly (see note 63).

[66] C. Díaz Pimentel, “Efectos adversos: El lado B de las medicinas psiquiátricas,” Salud con Lupa (June 4, 2023), https://saludconlupa.com/salud-mental/efectos-adversos-el-lado-b-de-las-pastillas-psiquiatricas/; P. Smith Castro, “La nueva ley de salud mental: ¿Un cambio de paradigma?,” Sociedad y Discapacidad (January 1, 2021), https://www.sodisperu.org/notas/la-nueva-ley-de-salud-mental.

[67] Tovar and Romero (see note 33); Videnza Consultores (see note 27); R. López Linares, R. Espinoza Carrillo, and J. Llamoza Jacinto, Reforma de salud con medicamentos para tod@s (Red Peruana por una Globalización con Equidad, 2014).

[68] Ministerio de Salud, “Observatorio peruano de productos farmacéuticos,” https://opm-digemid.minsa.gob.pe/.

[69] Peru, Ley No. 31112, Ley que establece el control previo de operaciones de concentración empresarial (2021); L. Alarcón, “Concentración empresarial: Indecopi aprobó 26 fusiones con la ley antimonopolio,” Ojo Público (July 2, 2023), https://ojo-publico.com/sala-del-poder/indecopi-aprobo-26-fusiones-empresariales-la-ley-antimonopolio.

[70] I. L. Duarte Turriago, J. X. Restrepo Andrade, S. R. Fernández Hurtado, and L. A. Martínez Martínez, “Impacto de la regulación de precios de medicamentos en Colombia,” in S. R. Fernández Hurtado and L. Beltrán García (eds), Cultura tributaria: Relevancia ante rentabilidad empresarial (Editorial Universidad Santiago de Cali, 2021).