New Legislation Criminalizing Sex Work in Kazakhstan Is Cause for Concern

PERSPECTIVE Vol 27/2, 2025, pp. 343-349 PDF

Olivia Cordingley, Natalya Zholnerova, Ekaterina Grigorchuk, Denis Gryazev, Karina Alipova, Sholpan Primbetova, Assel Terlikbayeva, Brooke West, Victoria Frye, and Tara McCrimmon

Introduction

In recent years, global trends in sex work legislation have been mixed, with many countries maintaining or expanding punitive approaches despite growing advocacy for decriminalization. Some governments, particularly in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and parts of Africa, have intensified crackdowns on sex work under the guise of public health or anti-trafficking efforts, often increasing surveillance, fines, and police harassment.[1] At the same time, there has been a notable rise in grassroots and international human rights advocacy pushing for the decriminalization of sex work, citing its potential to reduce violence, improve health outcomes, and uphold the rights of sex workers.[2] However, progress has been uneven, and the global policy environment remains largely hostile, with only a few countries, such as New Zealand and parts of Australia, adopting fully decriminalized models.[3]

Like many countries in the region, Kazakhstan has intensified enforcement measures under the banner of public order and anti-trafficking. Last year, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev signed Law No. 110-VIII on Countering Human Trafficking.[4] Upon taking effect in September 2024, this law redefined the parameters of sexual services in the context of anti-trafficking efforts, which has raised concern among public health and human rights experts due to its potential consequences for those engaged in sex work. By broadly defining potential victims of human trafficking to include individuals in vulnerable positions due to socioeconomic factors, such as homelessness or unemployment, this legislation conflates sex work with trafficking and assumes that all individuals engaged in sex work are coerced. While the stated objectives—protecting women and children from exploitation—may be well-intentioned, the practical implications of this legislation may disproportionately harm women who engage in sex work, violating their fundamental human rights and undermining their health and safety.

Sex work in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan’s sex work profession is diverse and fluid, encompassing individuals of various ages, genders, and ethnic backgrounds, who work in public venues, informal networks, and private settings. The Kazakhstan Scientific Center for Dermatology and Infectious Disease (KSCDID), which is part of the Ministry of Health, conducts periodic surveillance of sex work in the context of HIV prevention program planning. In 2024, KSCDID estimated that there were approximately 21,980 sex workers in Kazakhstan; however, this may not capture the full extent of sex work in the country.[5] Our research identified additional groups of women who exchanged sex occasionally or exchanged sex for drugs, goods, or other services and who were likely not included in official estimates.[6] Additionally, official estimates exclude men who have sex with men and transgender individuals who engage in sex work, as KSCDID classifies these as a separate key population.

Sex workers are highly marginalized in Kazakh society. While there has been a focus on their sexual health, sex workers face a broad range of health and social challenges. In Kazakhstan, specialty clinics that serve sex workers are locally referred to as AIDS centers or “friendly clinics.” These clinics provide HIV-related services, including testing for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV testing, and referrals. Mental health challenges are often overlooked, although prior research has identified a 52.5% prevalence of past-week suicidal ideation among a sample of 400 women who exchange sex and use drugs.[7] Sex workers are subjected to violence from both intimate partners and clients, as well as from law enforcement, including coercion or extortion into providing sex to avoid being detained or arrested.[8] The Kazakhstani government has taken no measures to protect individuals engaged in sex work and has tried to downplay its existence.[9] Further, sex workers face high levels of stigma and discrimination in health care settings. According to the most recent (2024) Stigma Index report, nearly half (45.7%) of women who exchange sex and are living with HIV are afraid that health care professionals will treat them poorly or disclose their HIV status, and nearly one-third (28.6%) have had a prior negative experience.[10] Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic led to changes in how sex work operated in Kazakhstan. Lockdowns and restrictions reduced clientele and drove sex work underground, eroding social networks and forcing some into more precarious work circumstances.[11] Law No. 110-VIII, which increases criminal-legal exposure, could make the risks of violence and exploitation from these changes even greater.

Legal frameworks for sex work

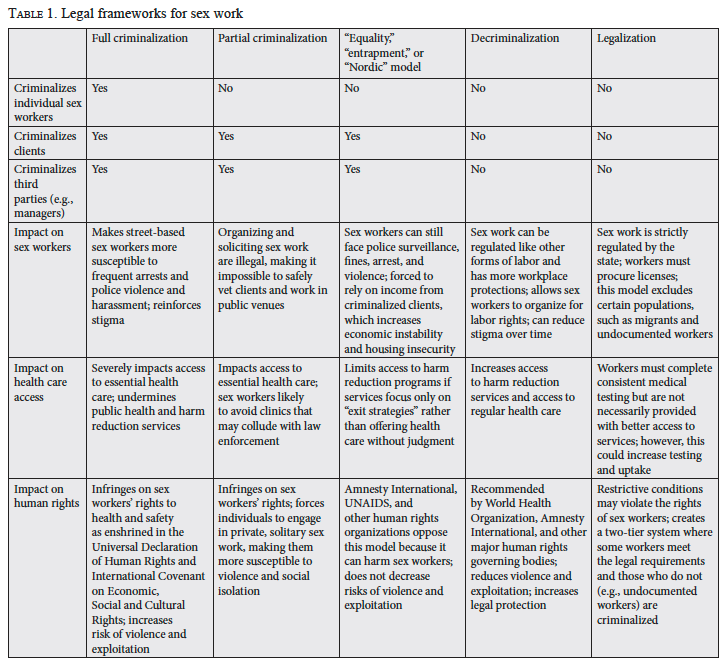

Sex work laws by country tend to fall into one of several legal frameworks: criminalization, partial criminalization, the “Nordic model,” decriminalization, and legalization.[12] These frameworks are described in Table 1. Decriminalization is widely considered to provide the best protections for public health and for women engaged in sex work, and it is the model supported by sex workers, advocates, and international organizations such as the World Health Organization.[13]

Prior to 2024, Kazakhstan followed a partially decriminalized model of sex work regulation, where engaging in sex in exchange for goods or services was not deemed illegal, but soliciting in public locations (article 449 of the Administrative Code) and brothel-keeping (article 450) were.[14] Buying sex is generally not an offense in Kazakhstan, except where a client knowingly receives sexual services from a minor, which is criminalized. Recent amendments also introduced explicit criminal liability for providing sexual services online in real time (e.g., webcam prostitution). As mentioned, these laws were frequently abused by police, as women engaged in sex work are frequently harassed by police or detained for “administrative violations.”[15]

Potential impacts of Law No. 110-VIII

The health and safety of sex workers in Kazakhstan will be severely compromised under this new legislation. Between 2016 and 2020, Kazakhstan opened 161 criminal cases related to sex work, the majority of which relate to organizing sex work; this is likely to increase under the new legislation.[16] Moreover, as we have seen in Canada and northern Europe, legislation that inadvertently or purposively conflates sex work with trafficking increases the policing of sex work communities in the name of stopping it. A robust body of prior research has documented the detrimental effects of increased policing in a context of partial and complete criminalization, including violence from clients, condomless sex, and HIV/STI incidence, which drive sex work underground and make women hesitant to seek care.[17] Policing can also can cause treatment disruptions for HIV.[18] In Europe and Canada, police surveillance and harassment of sex workers, under the guise of preventing trafficking, often intersects with racial profiling and migration policies.[19] Moreover, reforms to sex work legislation that stop short of full decriminalization do not reduce these negative effects. For example, in Canada, a 2014 shift from full criminalization to the Nordic Model (criminalizing the clients of sex workers) had no impact on reduction in violence.[20] In contrast, sex workers in New Zealand report that the country’s 2003 shift to decriminalization improved relationships between sex work communities and the police, and made women more comfortable reporting abuse.[21] Increased policing under this new legislation will likely shift sex work in Kazakhstan into private and unregulated settings. This transition will increase the risk of exploitation and violence by partners and police, with additional barriers to seeking legal protection against such behaviors. By further pushing sex work into the shadows, the legislation also limits the ability of sex workers to engage in harm reduction services, such as HIV testing, pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake, and STI treatment. This diminished access may increase the likelihood of HIV/STI transmission not only among sex workers but also within the broader population. Our research and work lead us to believe that this criminalization will worsen social isolation, depriving sex workers of peer support systems that often act as lifelines for accessing resources and harm reduction services.

In the months since this law has taken effect, we have begun to see both predicted and unpredicted impacts. Local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have reported increased demand for support services across the country, as sex workers are persecuted by the police. There are rumors of extortion by the police, threats, pressure, fines, persecution, targeting, and public exposure of sex workers in the media. There is a lack of clarity among service providers working with those engaged in sex work. The change has created widespread confusion among service providers who work with women engaged in sex work, particularly in determining what routine services, or advertising for such services, may be construed as “facilitating” sex work. Many providers do not fully understand the changes to the law, and state agencies offer conflicting interpretations. This uncertainty has disrupted service providers’ outreach to and support for sex workers. Finally, civilians often lack clarity on what constitutes “other sexual services,” whether it be online advertising, third parties (organizers, apartment tenants, pimps), or strictly sex work. This ambiguity contributes to an environment where sex workers become the target of harassment and violence, reflecting a broader pattern in which vaguely defined and inconsistently enforced laws fuel fear, misinformation, and confusion.

Call to action

Reversal of this legislation and decriminalization of sex work is essential to ensuring the safety, health, and dignity of individuals working in the sex industry. At the very least, Kazakhstan should consider clarifying the law to distinguish between consensual sex work and trafficking, aligning with international public health guidance. However, in the meantime, the following steps are needed:

Ensure health care access

Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Health should scale up HIV self-testing by increasing the number of distribution points and enabling individuals to order tests online. To ensure equitable access to care for sex workers, the Ministry of Health should expand low-barrier strategies by establishing more friendly clinics near sex work venues and integrating online scheduling tools for time-specific appointments. Additionally, friendly clinics should extend their operating hours into the late afternoon, evenings, and weekends to accommodate more schedules. These clinics could be transformed into one-stop shops by offering a broader range of services beyond HIV and STI testing and condom distribution.

Protect the rights and safety of sex workers

Immediate action is needed to protect the rights and safety of sex workers in Kazakhstan. NGO and medical service provider efforts should include educating women who exchange sex about their legal rights and the current status of sex work under Kazakhstan’s administrative and criminal codes. NGOs should organize safety trainings that cover both physical and digital security. Centralized access to safety resources should be made available through dedicated websites and social media platforms. Additionally, an emergency panic button system should be developed and implemented to provide immediate access to protection. Free or low-cost legal consultations should also be offered at accessible and convenient locations to ensure that sex workers can seek justice and support without barriers.

Support nongovernmental organizations

NGOs that support sex workers in Kazakhstan require additional resources and structural support to effectively meet the needs of this population. Increased funding is essential to expand the scope of preventive, legal, medical, and social services provided by these organizations. Clear service guidelines should be developed to define the legal rights and limitations of NGOs working with sex workers, clarify mandatory reporting requirements (including protocols for sharing client data), and outline the legal support available to NGO staff. Medical and social service providers should receive training on how to work respectfully and effectively with sex workers, in alignment with international and community-led standards, and on documenting human rights violations in accordance with Kazakhstani legislation. Outreach workers also need enhanced training, particularly in responding to gender-based violence and making appropriate referrals, to better support women who exchange sex.

Strengthen legal protections for sex workers

Advocacy efforts should target key national and international actors, including Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Health, and Ministry of Labor and Social Protection, as well as UN Women. Submitting shadow or alternative reports to United Nations bodies such as the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women and the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights is also critical to holding the government accountable for protecting the rights of sex workers. Particular attention must be paid to the rights of migrant sex workers, who face heightened vulnerability and are often deterred from reporting violence due to fear of deportation. Efforts should be made to systematically document human rights violations against migrant sex workers, ensure that reporting abuse does not endanger their legal status, and develop dedicated support programs with trained specialists who understand the specific needs of this population.

The international community, including human rights organizations and public health advocates, must apply pressure on the Kazakhstani government to repeal harmful legislation and implement evidence-based policies that align with global human rights standards. While legal and policy reforms are underway, interim harm reduction strategies should be implemented to mitigate the direct harm experienced by sex workers and the broader societal consequences of criminalization.

Olivia Cordingley, MSW, is a PhD candidate at the Drexel Dornsife School of Public Health, Philadelphia, United States.

Natalya Zholnerova is the director of Amelia, a nongovernmental organization in Taldykorgan, Kazakhstan.

Ekaterina Grigorchuk is a monitoring and evaluation specialist at the Kazakhstan Union of People Living with HIV.

Denis Gryazev is a coordinator at the Global Health Research Center of Central Asia, Almaty, Kazakhstan.

Karina Alipova is a coordinator at the Global Health Research Center of Central Asia, Almaty, Kazakhstan.

Sholpan Primbetova, PharmD, MSSW, is a PhD candidate at Al-Farabi Kazakh National University and the deputy regional director at the Global Health Research Center of Central Asia, Almaty, Kazakhstan.

Assel Terlikbayeva, MD, is regional director at the Global Health Research Center of Central Asia, Almaty, Kazakhstan.

Brooke West, PhD, is an associate professor of social work at the Columbia University School of Social Work, New York City, United States.

Victoria Frye, DrPH, is a professor of social work and co-director of the Social Intervention Group at the Columbia University School of Social Work, New York City, United States.

Tara McCrimmon, DrPH, MPH, MIA, is a postdoctoral research fellow in the Department of Psychiatry at the Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, United States.

Please address correspondence to Olivia Cordingley. Email: oc89@drexel.edu.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2025 Cordingley, Zholnerova, Grigorchuk, Gryazev, Alipova, Primbetova, Terlikbayeva, West, Frye, and McCrimmon. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

[1] UNAIDS, “Stigma, Criminalization and Under-Investment Are Driving Worrying Rises in New HIV Infections in Eastern Europe and Central Asia” (July 22, 2024), https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/pressreleaseandstatementarchive/2024/july/20240722_eastern-europe-central-asia.

[2] Human Rights Watch, “Landmark UN Report Calls for Sex Work Decriminalization” (November 28, 2023), https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/11/28/landmark-un-report-calls-sex-work-decriminalization.

[3] Global Network of Sex Work Projects, “Global Mapping of Sex Work Laws,” https://www.nswp.org/sex-work-laws-map; Global Network of Sex Work Projects, Sex Work and the Law: Understanding Legal Frameworks and the Struggle for Sex Work Law Reforms.

[4] Republic of Kazakhstan, № 110-VIII ҚРЗ «Адам саудасына қарсы іс-қимыл туралы» Заңы (Law No. 110-VIII of the Republic of Kazakhstan: On Countering Human Trafficking), https://zan.kz/ru/Document/DetailById?documentId=c50ef2d9-92d3-4007-8ef6-0582d735c5ef.

[5] Kazakh Scientific Center for Dermatology and Infectious Disease, “HIV Figures and Facts” (2024), https://kncdiz.kz/en/aids/aids/facts_and_figures/.

[6] T. McCrimmon, T. I. Mukherjee, A. Norcini Pala, et al., “Typologies of Sex Work Practice and Associations with the HIV Risk Environment and Risk Behaviors in Kazakhstan,” AIDS and Behavior 28/11 (2024).

[7] C. Vélez-Grau, N. El-Bassel, T. McCrimmon, et al., “Suicidal Ideation Among Women Who Engage in Sex Work and Have a History of Drug Use in Kazakhstan,” Mental Health and Prevention 23 (2021).

[8] T. I. Mukherjee, A. Terlikbayeva, T. McCrimmon, et al., “Association of Gender-Based Violence with Sexual and Drug-Related HIV Risk Among Female Sex Workers Who Use Drugs in Kazakhstan,” International Journal of STD and AIDS 34/10 (2023); T. I. Mukherjee, A. Norcini Pala, A. Terlikbayeva, et al., “Social and Structural Determinants of Health Associated with Police Violence Victimization: A Latent Class Analysis of Female Sex Workers Who Use Drugs in Kazakhstan,” International Journal of Drug Policy 106 (2022).

[9] Z. Raissova, “Kazakhstan: Existence of Sex Work Is Not Recognised by the State,” Central Asian Bureau for Analytical Reporting (2021), https://cabar.asia/en/kazakhstan-existence-of-sex-work-is-not-recognised-by-the-state.

[10] Central Asian Association of PLWH, “People Living with HIV Stigma Index 2.0” (2024), https://kncdiz.kz/en/news/item/8780/; O. Cordingley, T. McCrimmon, B. S. West, et al., “Preferences for an HIV Self-Testing Program Among Women Who Engage in Sex Work and Use Drugs in Kazakhstan, Central Asia,” Research on Social Work Practice 33/3 (2023); T. McCrimmon, V. Frye, M. Darisheva, et al., “‘Protected Means Armed’: Perspectives on Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Among Women Who Engage in Sex Work and Use Drugs in Kazakhstan,” AIDS Education and Prevention 35/5 (2023).

[11] V. A. Frye, N. Zholnerova, E. Grigorchuk, et al., “Impact of COVID-19 on Women Who Exchange Sex and Use Drugs in Kazakhstan: Phase 1 Results from AEGIDA” (presentation at the 24th International AIDS Conference, August 29, 2022, Montreal, Canada); O. Cordingley, T. McCrimmon, B. West, et al., “Information-Sharing Within Social Networks of Women Who Exchange Sex and Use Drugs/Alcohol in Kazakhstan: Implications for Increasing Consistent HIV Testing” (presentation at the 25th International AIDS Conference, July 21, 2024, Munich, Germany).

[12] Global Network of Sex Work Projects, “Global Mapping” (see note 3).

[13] World Health Organization, UNFPA, UNAIDS, et al., Implementing Comprehensive HIV/STI Programmes with Sex Workers: Practical Approaches from Collaborative Interventions (2013).

[14] Қазақстан Республикасының Әкімшілік құқық бұзушылық туралы кодексі 2014 жылғы 5 шілдедегі № 235-V ҚРЗ (“Code on Administrative Offenses in the Republic of Kazakhstan, 5 July 2014, Law No. 235-V”), https://zan.kz/en/Document/DetailById?documentId=57574b70-1606-4326-881c-145aef275bac, secs. 449–450.

[15] Mukherjee et al. (2022, see note 8); Raissova (see note 9).

[16] Raissova (see note 9).

[17] L. Platt, P. Grenfell, R. Meiksin, et al., “Associations Between Sex Work Laws and Sex Workers’ Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Quantitative and Qualitative Studies,” PLoS Medicine 15/12 (2018).

[18] S. M. Goldenberg, K. Deering, O. Amram, et al., “Community Mapping of Sex Work Criminalization and Violence: Impacts on HIV Treatment Interruptions Among Marginalized Women Living with HIV in Vancouver, Canada,” International Journal of STD and AIDS 28/10 (2017); K. Shannon, M. Rusch, J. Shoveller, et al., “Mapping Violence and Policing as an Environmental-Structural Barrier to Health Service and Syringe Availability Among Substance-Using Women in Street-Level Sex Work,” International Journal of Drug Policy 19/2 (2008).

[19] B. McBride, S. M. Goldenberg, A. Murphy, et al., “Protection or Police Harassment? Impacts of Punitive Policing, Discrimination, and Racial Profiling Under End-Demand Laws Among Im/Migrant Sex Workers in Metro Vancouver,” SSM – Qualitative Research in Health 2 (2022); N. Vuolajärvi, “Governing in the Name of Caring: The Nordic Model of Prostitution and Its Punitive Consequences for Migrants Who Sell Sex,” Sexuality Research and Social Policy 16/2 (2019); H. Millar and T. O’Doherty, “Racialized, Gendered, and Sensationalized: An Examination of Canadian Anti-Trafficking Laws, Their Enforcement, and Their (Re)Presentation,” Canadian Journal of Law and Society 35/1 (2020).

[20] A. L. Crago, C. Bruckert, M. Braschel, and K. Shannon, “Violence Against Sex Workers: Correlates and Changes Under ‘End-Demand’ Legislation in Canada; A Five City Study,” Global Public Health 17/12 (2022).

[21] L. Armstrong, “From Law Enforcement to Protection? Interactions Between Sex Workers and Police in a Decriminalized Street-Based Sex Industry,” British Journal of Criminology 57/3 (2017); L. Armstrong, “‘I Can Lead the Life That I Want to Lead’: Social Harm, Human Needs and the Decriminalisation of Sex Work in Aotearoa/New Zealand,” Sexuality Research and Social Policy 18/4 (2021).