Conceptualizing the Child’s Right to Oral Health: A Rights-Based Approach to Dental Caries

S. Dominique Mollet

Abstract

Dental caries is the most common noncommunicable disease globally and is a substantial burden for both adults and children, yet it remains largely neglected. The World Health Organization recognized the right to oral health in 2024. This paper introduces a comprehensive framework for children’s right to oral health based on the provisions of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. It demonstrates that although human rights treaties do not explicitly recognize the right to oral health, oral health, and particularly dental caries, is a matter of human rights. The first part of the paper clarifies how dental caries is a child rights matter, while the second part proposes a rights-based approach to the regulation of its risk factors.

Introduction

Oral diseases have been largely neglected in public health legal scholarship, even though they remain the most prevalent noncommunicable disease (NCD) worldwide.[1] Globally, untreated dental caries (tooth decay) poses a substantial NCD burden for children and adults; two billion people have untreated dental caries in permanent teeth and 514 million in primary teeth.[2] The disease is multifactorial—that is, its incidence is connected to a complex set of factors, including sugars ingestion, oral hygiene, fluoride exposure, and oral health care. If these factors are regulated adequately, dental caries is largely preventable.[3] Dental caries is also associated with health inequities; for example, its occurrence is more common among children of low socioeconomic status.[4] It has severe short- and long-term consequences; its prevalence in childhood predicts poor oral and general health outcomes in later life, and, via socio-behavioral factors, it presents a high risk of passing caries on to future generations.[5] A failure to address the underlying causes of dental caries fosters and exacerbates existing inequalities.

Oral health is rising on the global agenda, particularly with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2024 adoption of the Global Strategy and Action Plan on Oral Health, which recognizes the right to oral health.[6] Although there is also increasing support for a rights-based approach to oral health in the dental and public health literature, a comprehensive analysis of the right to oral health remains unresolved.[7] A rights-based approach, particularly focusing on children’s rights, is pertinent because it can offer a shift from the focus on individual responsibility toward addressing dental caries, particularly its prevention, at a population level. Accordingly, this paper conceptualizes children’s right to oral health, based on the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).[8] The analysis is restricted to dental caries in children, one of the main oral conditions and the main NCD among children globally.[9] In the first section, I describe the background against which the human rights analysis is conducted. Subsequently, I analyze how dental caries is a matter of children’s rights and requires upstream measures for its prevention. I then explore what a children’s rights-based approach to preventing dental caries entails, with particular attention to four risk factors that can be addressed by laws and regulations: (1) sugars ingestion; (2) oral hygiene; (3) fluoride exposure; and (4) oral health care attendance.

Background and methodology

The prevention of NCDs is a matter of human rights law; not only does human rights law provide a mechanism to hold governments accountable, but the interpretation of rights by treaty bodies can similarly guide the balancing of (legal) measures.[10] Substantively, scholars have extensively analyzed human rights in relation to NCD risk factors.[11]

Within the field of public health, including dental public health, a shift from an existing individualized focus toward upstream policies is simultaneously emerging.[12] Traditionally, dental professionals occupied a central role in the prevention of oral diseases, but it is increasingly recognized that population-level prevention and promotion practices must be strengthened.[13] Consequently, dental researchers have discussed the potential of integrating oral diseases into the NCD agenda.[14] The fact that oral diseases—in this case, dental caries—share risk factors with other NCDs provides an opportunity for states to jointly promote oral health and general health through the “common risk factors approach.”[15]

A gap between the two bodies of scholarship—(human rights) law and oral health—remains when it comes to the right to oral health, although a few studies have considered human rights and oral health.[16] For example, David Manton, Jan Wollgast, Brigit Toebes, and I developed a right to health-based approach to dental caries, while Gillian Jean et al. provide a conceptual study on a rights-based approach to oral health.[17] The latter studies the practical status quo in the area of oral health: Is oral health recognized as a human right in existing policies and health systems?[18] Rightfully so, the authors conclude that “the rights status of oral health is not settled.”[19] They come to this conclusion, however, following the assumption that “rights only exist when duty bearers accept the obligation to be accountable for progressive right realisation.”[20]

In contrast to the above assumption, this paper analyzes the right to oral health based on human rights law on paper. Accordingly, the legal value of human rights as understood here arises from the fact that by acceding to and ratifying human rights treaties, states accept the obligations laid out in them.[21] I adopt a doctrinal method to analyze the content of children’s right to oral health. The use of the phrase “the right to” does not imply that I wish to invent a novel, autonomous right (lex ferenda). Rather, I seek to analyze what children’s right to oral health consists of within the context of the ICESCR and CRC specifically.

A common methodological challenge that human rights law scholars encounter concerns the risk of blurring the distinction between lex lata and lex ferenda in novel or progressive interpretations, as such interpretations inevitably rely on nonbinding interpretative practice and guidance offered by competent treaty bodies.[22] This paper therefore differentiates between hard law and authoritative interpretations. Treaty texts constitute hard law, which is interpreted with authoritative interpretations—namely, general comments, the reports of Special Rapporteurs, and concluding observations. General comments offer general interpretative guidance for the rights enshrined in the treaties, while the reports of Special Rapporteurs and concluding observations by treaty bodies provide guidance for domestic implementation. Finally, WHO reports and scientific literature are similarly used for the interpretation and concretization of the content of rights.[23]

Dental caries as a matter of human rights

The WHO’s Global Strategy and Action Plan recognizes that “achieving the highest attainable standard of oral health is a fundamental right of every human being.”[24] Human rights treaties do not explicitly recognize this right. However, because oral health is integral to overall health and well-being, it falls within the scope of the right to health as enshrined in article 12 of the ICESCR and article 24 of the CRC.[25] In line with the interdependence and indivisibility of human rights, the right to oral health goes beyond the domain of health.[26] This corresponds with the social determinants of health—the impact of conditions in which people live and “wider forces that shape the conditions of daily life” on health—which also asks for any health policies to be intertwined with wider (social and economic) policies.[27]

Given that oral health “encompasses psychosocial dimensions, such as self-confidence, well-being and the ability to socialize and work without pain, discomfort and embarrassment,” poor oral health, including that associated with dental caries, is a critical matter of social life and functioning, thereby affecting those rights related to the development of children (e.g., articles 6(2) and 27(1) of the CRC).[28] The impact on the enjoyment of these rights is further exacerbated given that the prevalence of dental caries is greater among vulnerable groups, including children with low socioeconomic status, and it fosters existing health inequalities and disparities.[29]

Dental caries limits the full realization of children’s right to health. In light of article 12(2)(c) of the ICESCR and article 24(2)(c) of the CRC, states are mandated to take measures necessary for the prevention of dental caries.[30] According to article 12(2)(a) of the ICESCR, states must take steps to ensure the healthy development of the child.[31] Given that childhood is constitutive of later (oral) health status and that dental caries in childhood has intergenerational and intragenerational effects, it is pertinent to target measures toward children to ensure the enjoyment of the right to health throughout life.[32] Finally, because severe untreated dental caries in children can affect eating, owing to pain, it may lead to underweight and stunting.[33] Therefore, under article 24(2)(c) of the CRC, states should consider dental caries as a potential cause of malnutrition.[34]

Further, the ICESCR and CRC indicate measures that contribute to the fulfillment of the right to health. Articles 12(2)(d) of the ICESCR and 24(2)(b) of the CRC prescribe states to ensure access to health care services in case of need, while article 24(2)(f) of the CRC requires the development of preventive health care services.[35] This corresponds with WHO’s Global Strategy and Action Plan, which has universal health coverage at the core of its vision, because ensuring equal access to oral health care services is an important component of effectively addressing dental caries.[36] Yet the multifactorial nature of the disease—driven, among other things, by sugars intake—and the associated social and commercial determinants of health, requires a response beyond health care.[37] This is supported by research that demonstrates that an individualized care approach does not suffice for reducing caries incidence in all segments of society.[38] Although the measurable behavior is that of individuals, the determinants of those behaviors, including social and commercial ones, are largely structural in nature and consequently should be addressed as such. The right to health similarly requires a supplementary focus on upstream, preventive measures that address the underlying determinants of health—for instance, the provision of adequate nutritious foods and information (article 24(2)(c) and (e) of the CRC).[39]

Poor child oral health, including (severe) dental caries, is also associated with missed school days and reduced academic development, an issue of children’s right to education (article 12(1)(e) of the CRC).[40] This is especially problematic in light of the increased prevalence of dental caries among persons of low socioeconomic status and the pertinence of socio-behavioral factors. Accordingly, article 6(2) of the CRC—one of the general principles prescribing the right to life and the obligation to ensure the development of children that should be interpreted “in its broadest sense as a holistic concept”—is at stake as well.[41] The best interest of the child, as one of the general principles of the CRC and stipulated in article 3, underpins all the above. As a substantive right, an interpretative principle, and a rule of procedure, the best interest principle mandates states to ensure that it is applied throughout its structures and in all processes, and to consider the potential impact of all decisions and actions on children’s rights and interests.[42] Finally, in fulfilling the above rights and adopting measures, states are mandated to consider children’s views in all matters affecting the child (article 12(1) of the CRC).[43]

A rights-based approach to addressing dental caries risk factors

To identify state obligations in the context of children’s right to oral health with respect to dental caries, it is important to understand the etiology of dental caries and its modifiable risk factors. Doing so will inform a rights-based framework to guide the development of dental caries control strategies.

WHO describes the process of dental caries as the “destruction of teeth [that] results when microbial film (plaque) formed on the tooth surface converts the sugars contained in foods and drinks into acids, which dissolve tooth enamel and dentine over time.”[44] In other words, frequent sugars consumption modifies the microbial balance of the plaque into one that is cariogenic. This cariogenic plaque is readily able to metabolize sugars, forming acids that dissolve the two dental hard tissues—enamel (the hard outer surface of tooth) and dentine (the layer between enamel and the dental pulp)—leading to carious lesion development.[45] To prevent caries, the creation and persistence of these acids must be interrupted.

Reducing the risk of caries development involves a combination of factors.[46] Given the primary role of sugars and their pathological influence on the dental plaque microbiota in dental caries development, it is important that the amount and frequency of sugars ingested be limited.[47] Dental plaque, which builds up on tooth surfaces, needs to be regularly removed by brushing with a fluoride toothpaste and interdental cleaning, thereby removing the cariogenic plaque (if present) and limiting the time it is present on the tooth surface.[48] Exposure to low levels of fluoride, either through toothpaste or community water fluoridation, strengthens the resistance of enamel to demineralization (dissolution or cavity formation).[49] Oral health practitioners play an important role in preventing and managing dental caries by identifying a patient’s risk of developing dental caries, arresting existing carious lesions (that is, halting the progression of active carious lesions), and treating carious lesions with restorations or extractions.[50]

The remainder of this section is structured according to the aforementioned risk factors that can be addressed by laws and policies: (1) sugars ingestion; (2) oral hygiene; (3) fluoride exposure; and (4) the dental health care system.

Free sugars ingestion

Sugars ingestion is a key dental caries risk factor; limiting the frequency and amount of sugars ingested curbs the development of cariogenic biofilm and in turn significantly lowers dental caries risk.[51] Although dental caries development is fueled by all dietary sugars, it is important to distinguish between free sugars and intrinsic sugars.[52] Free sugars are considered nonessential nutrients whose intake is linked to a number of NCDs (including dental caries) and encourages further consumption.[53] Consequently, WHO strongly recommends that they represent less than 10% of total energy intake.[54] Intrinsic sugars are those naturally present in whole fresh fruits and vegetables and are recommended as part of a healthy diet.[55]

The right to health and the right to an adequate standard of living, including adequate food (hereinafter the right to adequate food), can inform upstream measures to address sugars consumption.[56] As signatories, states must adopt measures to prevent NCDs, including those related to diet.[57] The progressive realization of the right to adequate food implies that obligations stretch beyond ensuring “a minimum package of calories, proteins and other specific nutrients.”[58] In fact, nutrition is among the key determinants of children’s health, and the right to health mandates states to ensure the provision of adequate nutritious foods and combat malnutrition.[59]

The obligations under the right to health in this context are various. The obligation to respect the right to health can be interpreted to mean that states should not act in a manner that is likely to result in preventable, diet-related morbidity and mortality—such as by incentivizing the consumption of unhealthy products.[60] The obligation to protect requires states to regulate the activities of industries whose practices may be detrimental to their health.[61] The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights classifies the failure to protect consumers from practices detrimental to health by manufacturers of food as a violation of this obligation.[62] The obligation to fulfill means that individuals must be assisted with, among other things, the provision of nutritiously safe food and information.[63]

More particularly, treaty bodies and Special Rapporteurs have addressed “sugars” explicitly, especially in relation to the food environment. For instance, the Committee on the Rights of the Child refers to sugars in its General Comment 15, stating that “children’s exposure to ‘fast foods’ that are high in … sugar … should be limited.”[64] The committee also notes that the marketing of such foods should be regulated and their availability in schools limited.[65] The committee also referred to sugars in its concluding observations to Tonga in 2019, suggesting that the state “discourage school canteens from serving ‘fizzy’ drinks, junk food and food high in sugar.”[66] Finally, the Special Rapporteur on the right to health, Tlaleng Mofokeng, directly signals the increased presence of sugars, among other substances, in food systems and food environments as drivers of health, specifically NCDs.[67]

Specific measures that have been suggested or identified as good practices by Special Rapporteurs and in general comments in the context of food include sugar(-sweetened beverage) taxes; advertising bans and restrictions for certain foods; mandatory (front-of-pack) labeling measures; fiscal measures and procurement policies to incentivize the agricultural production of, among other products, vegetables and fruits; the establishment of health-related requirements for investments by transnational companies; limiting the availability of certain food products in schools; and involving schools in health strategies.[68] In this regard, it must be highlighted that a number of these structural measures incur little or no cost for states and contribute to the realization of the right to health. In light of the attainability of the right to health, these measures should thus be prioritized.[69]

Oral hygiene

Oral self-care—toothbrushing and interdental cleaning—is crucial in maintaining a favorable oral environment; doing so removes the buildup of dental plaque. Apart from the question of which policy tools are available to states to regulate hygiene practices, it is important to first consider the extent to which state obligations stretch here: Can a state step into the bathroom and address children’s brushing habits through legal interventions?

Articles 5 and 18 of the CRC provide guidance in this regard. Article 5 prescribes a hands-off approach and stipulates that states must respect the responsibilities, rights, and duties of parents in guiding their children in the exercise of their rights.[70] Article 18(2) sets out that states have to provide “appropriate assistance to parents and legal guardians in the performance of their child-rearing responsibilities” to guarantee the rights enshrined in the convention.[71] In other words, states must strike a balance: they have to respect, and thereby not interfere with, the relationship between caregivers and children, while providing those caregivers with the means, such as funds and information, to ensure that children grow up in a manner that assures the furtherance of their rights.

Substantively, the right to health, along with the rights to information and education (articles 13, 24, and 29(1)(a) of the CRC), inform measures addressing oral hygiene as a risk factor for poor child oral health. Article 24(2)(e) of the CRC explicitly stipulates that, in pursuing the full implementation of children’s right to health, states must adopt measures “to ensure that all segments of society, in particular parents and children, are informed, have access to education and are supported in the use of basic knowledge of … hygiene.”[72] Under the obligation to fulfill (facilitate) the right to health, states must make an effort to “enable and assist individuals and communities to enjoy the right to health.”[73] The provision of information as a public health intervention corresponds with the balance between articles 5 and 18 of the CRC, described above.[74] The information provided should be physically accessible, understandable, and appropriate to children’s age and educational level.[75] The Committee on the Rights of the Child’s General Comment 15 suggests that such information be communicated via school curriculums, health services, and in other contexts for children who do not attend school.[76] Parents should be informed via multiple channels, including media and public information leaflets.[77]

Fluoride exposure

Fluoride mitigates caries lesion formation because it favors remineralization of the enamel and dentine, providing resistance against acids. Fluoride can be provided by brushing with a fluoride toothpaste, receiving professionally applied fluoride treatments, or through fluoridated community water supplies, dietary salt, or milk.[78]

In its topical version, fluoride qualifies as an essential medicine. Fluoride-containing dental preparations were added to the 22nd WHO Model List of Essential Medicines and the 8th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children in 2021.[79] This reinforces the framing of fluoride exposure as a matter of human rights law: since fluoride qualifies as an essential medicine, its provision falls within the core content of the right to health.[80] This means that this obligation is not to be realized progressively: rather, noncompliance with the obligation to make essential medicines available and accessible amounts to a violation of the right to health.[81]

Community water fluoridation has proven to be successful and has been rated as one of the 10 greatest public health interventions by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[82] As a population measure, it provides safe and equitable access to all and can in turn reduce oral health inequalities.[83] In this form, fluoride is a non-essential nutrient, which means that its intake is not needed for the body to perform essential physiological functions.[84] It must also be noted that the excessive intake of fluoride—for example, in contexts where fluoride is naturally present in water or food—can potentially be harmful.[85] In this regard, the so-called AAAQ (which stands for availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality) framework offers guidance for fluoride provision: it must be (1) available, (2) physically and economically accessible in a nondiscriminatory fashion, (3) culturally and ethically acceptable, and (4) medically appropriate and of good quality.[86]

The right to health offers discretion as to its precise implementation.[87] Rather, the standard set under the CRC and the ICESCR pledges that nutrients and medicines, including fluoride, must be administered (medically) appropriately.[88] This implies that states’ obligations include providing appropriate amounts of fluoride, for which there are guidelines.[89] In this regard, the obligation of states stretches to guarantee the rational and appropriate dispensation, sale, and usage of essential medicines so as to prevent adverse health effects.[90] The decision on the exact method of fluoride delivery is left to the state. In addition to this, individuals in all segments of society should be informed about the importance of fluoride exposure and the means of such exposure, and should be supported in making informed decisions about fluoride and their health.[91]

Oral health care

Health care plays a multifaceted role in caries management, ranging from preventive care to curative treatment.[92] In many countries, however, unmet needs for dental care still remain. This is related to, among other factors, limited coverage of dental care (for adults) (thereby leaving oral health care attendance dependent on individuals’ financial means), the unequal distribution of the oral health care workforce, and a preference for technology-based curative treatment.[93]

The right to health similarly reflects these roles.[94] Primarily, the obligation to fulfill the right to health mandates states to ensure the provision of health care.[95] There are multiple general factors that established health care systems must address, including the AAAQ requirements and the appropriate training of health care workers.[96] In addition, especially when it comes to children, the health care system should encompass not only curative services but also “prevention, promotion, treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care services.”[97]

The right to health requires the appropriate allocation of resources to prevent overt and covert forms of discrimination.[98] It is pertinent to note that the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights stipulates that “investments should not disproportionately favour expensive curative health services … often accessible only to a small, privileged fraction of the population, rather than primary and preventive care, benefiting a far larger part of the population.”[99] NCDs should also be addressed in preventive health care services, integrating “a combination of biomedical, behavioral, and structural interventions.”[100]

Many countries face difficulties ensuring access to oral health care for all, and the lack of universal coverage for oral health is signaled as a main concern in debates on oral health.[101] Considering the large number of countries in which oral health care services are provided by private parties and expenses are covered by out-of-pocket payments, the obligations concerning the economic accessibility of health care facilities and services (alternatively known as affordability) under the right to health must be highlighted.[102]

The child’s right to health is clear: universal access to primary health care services, into which oral health care should be integrated, for children should be of primary concern, and the inability to pay should not result in the denial of the child’s right to access health care.[103] Payment for such services should still be based on the principle of equity so that they remain affordable for all.[104] Accordingly, states have a special obligation to ensure that those with insufficient (financial) means have the necessary health insurance and that insurance is affordable for all.[105] In establishing such a system, states must make use of risk-pooling mechanisms that rely on equitable, means-based contributions.[106] Regardless of whether the insurance system is of public, private, or mixed nature, the responsibility remains with states to ensure its affordability.[107]

Finally, besides universal access to health care facilities and services, and the further requirements of health care provision, the right to health offers guidance concerning the environment in which health care is provided. In this regard, states should create an environment in which children and parents are enabled and encouraged to adopt health-seeking behavior.[108] Such an environment should encompass not only the availability of services but also high levels of health knowledge.[109] An example of such a stimulating environment includes the provision of health services within schools to promote health-seeking behavior.[110]

Conclusion

Child oral health and the prevention of dental caries has clear human rights dimensions. Oral health is an integral component of general health and affects children’s current and future health and development. This makes it a crucial component in ensuring the fulfillment of multiple rights. Reflecting on the analysis of state obligations to address risk factors, the need for upstream measures stands out, especially given resource restraints in many states. On the one hand, the current barriers to realizing the right to oral health care and its associated costliness indicate the shortcomings of policies focused primarily on oral health care. On the other hand, upstream measures—such as implementing a sugar tax, requiring front-of-pack labeling, or restricting advertising—can be implemented at minimal or no cost. The adoption of an upstream approach thus increases the attainability of the right to health, which increases the stringency of obligations arising from the right to health.

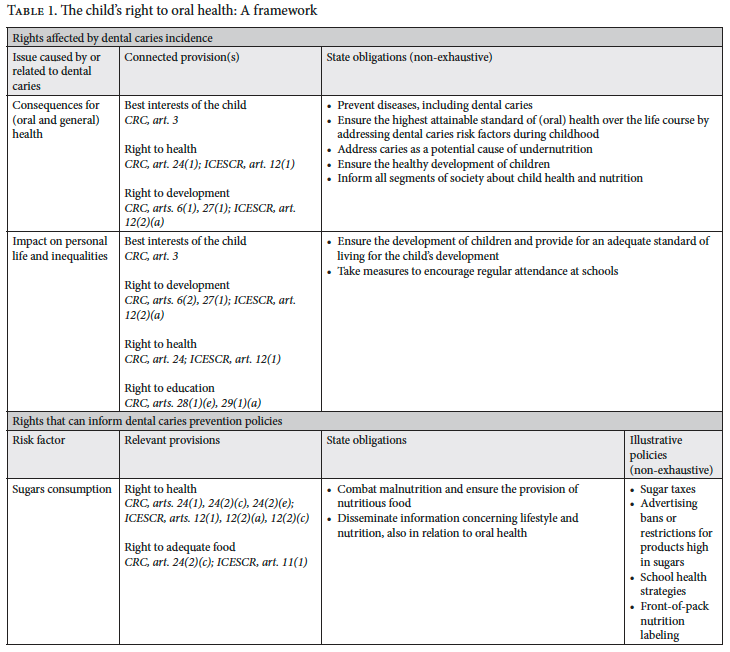

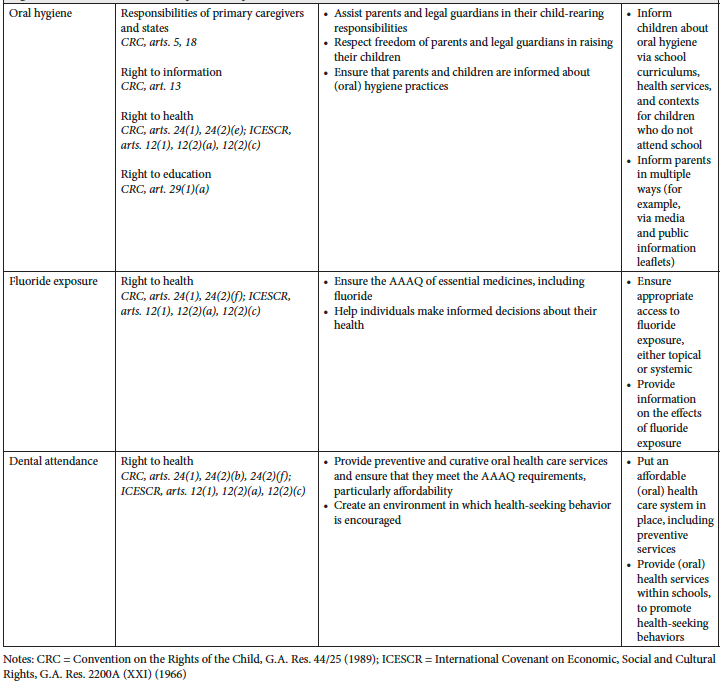

Table 1 summarizes a proposed framework for children’s right to oral health. This framework can be used by policy makers, advocates, and researchers to further public oral health, particularly in the context of dental caries as a disease. Additionally, it can inform future research on rights-based approaches to oral diseases, other NCDs in general, and associated risk factors. The rights identified can serve as legal tools to hold policy makers accountable and inform policy and practice in the field of oral health and childhood caries.

Human rights, especially children’s rights, can inform the development of a comprehensive approach to addressing dental caries incidence and risk factors, supplementing the current individualized approach with upstream measures.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for the feedback provided by and the stimulating discussions with my supervisors and colleagues Brigit Toebes, David Manton, Jan Wollgast, Meaghan Beyer, Marlies Hesselman, and Sandra Caldeira. I also thank the Danish Institute for Human Rights for organizing a PhD course on human rights research methods, where I presented and discussed the methods adopted for this paper and received feedback to enhance them.

S. Dominique Mollet, LLM, is a PhD candidate at the European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC), Ispra, Italy, and the Groningen Centre for Health Law, Faculty of Law, University of Groningen, the Netherlands.

Please address correspondence to the author. Email: s.d.mollet@rug.nl.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2025 Mollet. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

[1] World Health Organization, Global Oral Health Status Report: Towards Universal Health Coverage for Oral Health by 2030 (2022), p. 9.

[2] Ibid., p. 30.

[3] Ibid., pp. 36–37.

[4] Ibid., p. 1.

[5] Ibid., p. 1; D. M. Shearer and W. M. Thomson, “Intergenerational Continuity in Oral Health: A Review,” Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 38/6 (2010); D. M. Shearer, W. M. Thomson, J. M. Broadbent, and R. Poulton, “Maternal Oral Health Predicts Their Children’s Caries Experience in Adulthood,” Journal of Dental Research 90/5 (2011).

[6] World Health Organization, Global Strategy and Action Plan on Oral Health 2023–2030 (2024).

[7] See, for example, D. Mollet, G. Taylor, and B. Toebes, “Children’s Right to Oral Health,” British Medical Journal (2024); S. D. Mollet, D. J. Manton, J. Wollgast, and B. Toebes, “A Right to Health-Based Approach to Dental Caries: Towards a Comprehensive Control Strategy,” Caries Research 58/4 (2024); H. Benzian, A. Daar, and S. Naidoo, “Redefinining the Non-Communicable Disease Framework to a 6×6 Approach: Incorporating Oral Diseases and Sugars,” Lancet Public Health 8/11 (2023); G. Jean, E. Kruger, and V. Lok, “Oral Health as a Human Right: Support for a Rights-Based Approach to Oral Health System Design,” International Dental Journal 71/5 (2021).

[8] International Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI) (1966); Convention on the Rights of the Child, G.A. Res. 44/25 (1989).

[9] World Health Organization (2024, see note 6), p. 49; D. Richards, “Oral Diseases Affect Some 3.9 Billion People,” Evidence Based Dentistry 14/35 (2013); World Health Organization, Ending Childhood Dental Caries: WHO Implementation Manual (2019), p. 7.

[10] See, for example, L. Gentile, M. C. Campisi, and N. Chingore, “The Role of Human Rights in NCD Prevention and Control,” in N. Banatvala and P. Bovet (eds), Noncommunicable Diseases: A Compendium (Routledge, 2023); S. Gruskin, L. Ferguson, D. Tarantola, and R. Beaglehole, “Noncommunicable Diseases and Human Rights: A Promising Synergy,” American Journal of Public Health 104/5 (2014); D. Patterson, K. Buse, R. Magnusson, and B. Toebes, “Identifying a Human Rights-Based Approach to Obesity for States and Civil Society,” Obesity Review 20/Suppl 2 (2019).

[11] See, for example, Patterson et al. (see note 10); K. Ó Cathaoir, Children’s Rights and Food Marketing: State Duties in Obesity Prevention (Intersentia, 2022); C. Slattery, “Using Human Rights Law to Progress Alcohol Control,” European Journal of Risk Regulation 12/Special Issue 2 (2021); A. Constantin, O. A. Cabrera, B. Ríos, et al., “A Human Rights-Based Approach to Non-Communicable Diseases: Mandating Front-of-Pack Warning Labels,” Globalization and Health 17/85 (2021); M. E. Gispen and B. Toebes, Human Rights and Tobacco Control (Edward Elgar, 2020).

[12] R. G. Watt, B. Daly, P. Allison et al., “Ending the Neglect of Global Oral Health: Time for Radical Action,” Lancet 394/10194 (2019).

[13] Ibid.; World Health Organization (2024, see note 6), paras. 26–27, actions 23–33; P. Moynihan and C. Miller, “Beyond the Chair: Public Health and Governmental Measures to Tackle Sugar,” Journal of Dental Research 99/8 (2020).

[14] M. Charles-Ayinde, F. Cieplik, G. H. Gilbert, et al., “Action Needed on Oral Diseases within the Global NCD Agenda,” Journal of Dental Research (2025); R. H. Beaglehole and R. Beaglehole, “Promoting Radical Action for Global Oral Health: Integration or Independence?,” Lancet 394/10194 (2019); Benzian et al. (see note 7).

[15] World Health Organization (2024, see note 6), paras. 1, 14, action 23.

[16] Mollet et al., “A Right to Health-Based Approach to Dental Caries” (see note 7); G. Jean, Child Dental Health and Human Rights: Australia’s Health and Human Rights Obligations as a Signatory to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, PhD thesis (University of Western Australia, 2022), p. 4; G. Jean, E. Kruger, V. Lok, and M. Tennant, “The Right of the Child to Oral Health: The Role of Human Rights in Oral Health Policy Development in Australia,” Journal of Law and Medicine 28/1 (2020), p. 214; Jean et al. (2021, see note 7).

[17] Mollet et al., “A Right to Health-Based Approach to Dental Caries” (see note 7); Jean et al. (2021, see note 7).

[18] Jean et al. (2021, see note 7).

[19] Ibid. p. 356.

[20] Ibid.

[21] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see note 8), preamble; Convention on the Rights of the Child (see note 8), preamble.

[22] S. Egan, “The Doctrinal Approach in International Human Rights Law Scholarship,” in L. McConnel and R. Smith (eds), Research Methods in Human Rights (Routledge, 2018), pp. 32–33; M. Hesselman, Human Rights and Access to Modern Energy Services, PhD thesis (University of Groningen, 2023), pp. 16–18; F. Coomans, F. Grunfeld, and M. Kamminga, “Methods of Human Rights Research: A Primer,” Human Rights Quarterly 32/1 (2010), pp. 180–186 (note also the criticism phrased by the authors on pp. 183–184).

[23] Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 15, UN Doc. CRC/C/GC/15 (2013), para. 44; K. Ó Cathaoir and M. Hartlev, “The Child’s Right to Health as a Tool to End Childhood Obesity,” in A. Garde, J. Curtis, and O. De Schutter (eds), Ending Childhood Obesity: A Challenge at the Crossroads of International Economic and Human Rights Law (Edward Elgar, 2020), pp. 57, 59–60.

[24] World Health Organization (2024, see note 6), para. 15.

[25] Ibid., para. 2; International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see note 8), art. 12; Convention on the Rights of the Child (see note 8), art. 24.

[26] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000), para. 3.

[27] World Health Organization, “Social Determinants of Health” (May 6, 2025), https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/social-determinants-of-health; World Health Organization (2024, see note 6), para. 6.

[28] World Health Organization (2024, see note 6), para. 3; Convention on the Rights of the Child (see note 8), arts. 6(2), 27(1).

[29] World Health Organization (2019, see note 9), pp. 7, 8; D. A. Verlinden, S. A. Reijneveld, C. I. Lanting, et al., “Socio-Economic Inequality in Oral Health in Childhood to Young Adulthood, Despite Full Dental Coverage,” European Journal of Oral Sciences 127/3 (2019).

[30] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see note 8), art. 12(2)(c); Convention on the Rights of the Child (see note 8), art. 24(2)(c).

[31] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see note 8), art. 12(2)(a).

[32] Shearer et al. (2010, see note 5); Shearer et al. (2011, see note 5); Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 15, UN Doc. CRC/GC/C/15 (2013), paras. 16, 20; B. Ruiz, J. M. Broadbent, W. M. Thomson, et al., “Childhood Caries Is Associated with Poor Health and a Faster Pace of Aging by Midlife,” Journal of Public Health Dentistry 83 (2023).

[33] World Health Organization (2022, see note 1), p. 37.

[34] Convention on the Rights of the Child (see note 8), art. 24(2)(c).

[35] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see note 8), art. 12(2)(d); Convention on the Rights of the Child (see note 8), art. 24(2)(b) and (f).

[36] World Health Organization (2024, see note 6), paras. 1, 15–16.

[37] Ibid., paras. 26–27, actions 23–33; Watt et al. (2019, see note 12), p. 261; World Health Organization, “Sugars and Dental Caries,” https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sugars-and-dental-caries.

[38] Verlinden et al. (see note 29).

[39] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see note 8), art. 12(2)(c); Convention on the Rights of the Child (see note 8), arts. 24(2)(c) and (e).

[40] M. F. A. Quadri and B. Ahmad, “Elucidating the Impact of Dental Caries, Pain and Treatment on Academic Performance in Children,” International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 33/4 (2023); R. R. Ruff, S. Senthi, S. R. Susser, and A. Tsutsui, “Oral Health, Academic Performance, and School Absenteeism in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Journal of the American Dental Association 150/2 (2019); B. L. Edelstein and S. Reisine, “Fifty-One Million: A Mythical Number That Matters,” Journal of the American Dental Association 146/8 (2015); World Health Organization (2022, see note 1). On missed schooldays and reduced academic development in the context of CRC, see Convention on the Rights of the Child (see note 8), art. 28(1)(e); Committee on the Rights of the Child, Concluding Observations: United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, UN Doc. CRC/C/GBR/CO/4 (2008), para. 47(a); Committee on the Rights of the Child, Concluding Observations: Finland, UN Doc. CRC/C/15/Add.272 (2005), para. 42.

[41] Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 5, UN Doc. CRC/GC/2003/5 (2003), para. 12; N. Peleg, Perspectives on the Right to Development (Cambridge University Press, 2019), pp. 83, 97, 130.

[42] Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 14, UN Doc. CRC/C/GC/14 (2013), para. 6.

[43] Convention on the Rights of the Child (see note 8), art. 12(1); Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 12, UN Doc. CRC/C/GC/12 (2009), para. 122.

[44] World Health Organization (2019, see note 9), p. v.

[45] Ibid., p. 7.

[46] K. Divaris, “Predicting Dental Caries Outcomes in Children: A ‘Risky’ Concept,” Journal of Dental Research 95/3 (2016), pp. 248–254.

[47] World Health Organization (2019, see note 9), p. 16.

[48] Y. Lee, “Diagnosis and Prevention Strategies for Dental Caries,” Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 3/2 (2013), p. 108.

[49] World Health Organization (2019, see note 9), p. 19.

[50] Ibid., pp. 23–27.

[51] World Health Organization (2022, see note 1), p. 37; P. Moynihan and P. E. Petersen, “Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Dental Diseases,” Public Health Nutrition 7/1A (2004), p. 202.

[52] World Health Organization (2019, see note 9), p. 7.

[53] World Health Organization European Region, Sugars Factsheet (2022), pp. 1, 3; R. H. Lustig, L. A. Schmidt, and C. D. Brindis, “The Toxic Truth About Sugar,” Nature 482 (2012), p. 27.

[54] World Health Organization, Guideline: Sugars Intake for Adults and Children (2015), p. 4.

[55] Ibid., p. 7.

[56] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see note 8), arts. 11, 12.

[57] Ibid., art. 12(2)(c); Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health, Anand Grover, UN Doc. A/HRC/26/31 (2014), para. 13.

[58] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 12, UN Doc. E/C.12/1999/5 (1999), paras. 6, 16.

[59] Committee on the Rights of the Child (2013, see note 32), para. 18; Convention on the Rights of the Child (see note 8), art. 24(2)(c); Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 26), para. 36.

[60] United Nations General Assembly, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health, Tlaleng Mofokeng, UN Doc. A/78/185 (2023), para. 11; Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 26), paras. 34, 50.

[61] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 26), para. 35.

[62] Ibid., para. 51.

[63] Ibid. paras. 36–37.

[64] Committee on the Rights of the Child (2013, see note 32), para. 47.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Committee on the Rights of the Child, Concluding Observations: Tonga, UN Doc. CRC/C/TON/CO/1 (2019), para. 48(g).

[67] United Nations General Assembly (see note 60), paras. 22–31.

[68] Ibid., paras. 73, 77–78, 89, 90; Human Rights Council (see note 66), paras. 18–22, 25–26; Committee of the Rights of the Child (2013, see note 32), paras. 46–47.

[69] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see note 8), art. 12(1).

[70] Convention on the Rights of the Child (see note 8), art. 5.

[71] Ibid., art. 18(2).

[72] Ibid., art. 24(e) (emphasis added).

[73] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 26), para. 37.

[74] Convention on the Rights of the Child (see note 8), arts. 5, 18. See also Nuffield Council on Bioethics, Public Health: Ethical Issues (2007), p. xix.

[75] Committee on the Rights of the Child (2013, see note 32), para. 58.

[76] Ibid., para. 59.

[77] Ibid., para. 61.

[78] World Health Organization (2019, see note 9), pp. 19–20.

[79] World Health Organization, WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children: 8th List, 2021 (2021); World Health Organization, WHO Model List of Essential Medicines: 22nd List, 2021 (2021).

[80] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 26), para. 43(d).

[81] Ibid., paras. 43, 44, 47; Committee on the Rights of the Child (2013, see note 32), para. 73(b).

[82] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Ten Great Public Health Achievements – United States, 1900–1999” (April 2, 1999), https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00056796.htm.

[83] World Health Organization (2019, see note 9), p. 19; J. A. Atkinson, J. M. Jackson, G. Lowery, et al., “Community Water Fluoridation and the Benefits for Children,” Dental Update 50/7 (2013); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “CDC Scientific Statement on Community Water Fluoridation” (May 15, 2024), https://www.cdc.gov/fluoridation/about/statement-on-the-evidence-supporting-the-safety-and-effectiveness-of-community-water-fluoridation.html.

[84] European Food Safety Authority, “Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for Fluoride,” EFSA Journal 11/8 (2013), pp. 2–3.

[85] World Health Organization, “Chemical Safety and Health,” https://www.who.int/teams/environment-climate-change-and-health/chemical-safety-and-health/health-impacts/chemicals/inadequate-or-excess-fluoride.

[86] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 26), para. 12.

[87] Ibid. para. 53.

[88] Ibid., para. 12(d).

[89] The Community Guide, “Dental Caries (Cavities): Community Water Fluoridation” (April 2013), https://thecommunityguide.org/findings/dental-caries-cavities-community-water-fluoridation.html.

[90] Human Rights Council (see note 57), paras. 57–60.

[91] Convention on the Rights of the Child (see note 8), art. 24(2)(e); Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 26), para. 37.

[92] World Health Organization (2019, see note 9), pp. 23–27.

[93] World Health Organization (2024), para. 8; J. Winkelmann, J. Gómez Rossi, and E. van Ginneken, Oral Health Care in Europe: Financing, Access and Provision (European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2022), pp. 18–19.

[94] Convention on the Rights of the Child (see note 8), art. 24(2)(f); Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 26), para. 17.

[95] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 26), para. 36.

[96] Ibid., paras. 12, 36.

[97] Committee on the Rights of the Child (2013, see note 32), para. 25.

[98] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 26), para. 19.

[99] Ibid.

[100] Committee on the Rights of the Child (2013, see note 32), para. 62.

[101] Winkelmann et al. (2022, see note 93); World Health Organization (2024, see note 6), paras. 1, 11; J. Winkelmann, S. Listl, and E. van Ginneken, “Universal Health Coverage Cannot Be Universal Without Oral Health,” Lancet Public Health 8/1 (2023).

[102] Winkelmann (2022, see note 93).

[103] World Health Organization (2024, see note 6), paras. 17, 30, actions 4, 17, 58, 62; Committee on the Rights of the Child (2013, see note 32), paras. 29, 36.

[104] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 26), para. 12(b).

[105] Ibid., paras. 19, 36.

[106] Committee on the Rights of the Child (2013, see note 32), para. 114.

[107] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2000, see note 26), para. 36.

[108] Committee on the Rights of the Child (2013, see note 32), para. 30.

[109] Ibid., para. 30.

[110] Ibid., para. 36.