"Only on Paper": Rights vs. Reality for Gender-Based Violence Survivors in Rural Bolivia

Vol 27/1, 2025, pp. 59-71 PDF

Vanessa K. Voller, Mikaela Smith, Caterine Senzano Castro, Gabriella Barrozo, Fiorella Burgos, Dino Maccari, Pennye Nixon, Christie L. Martin, Lucy Mkandawire-Valhmu, Alex Mysler, Veronica Pellizzari, and Sarah J. Hoffman

Abstract

This paper presents testimony from a primary care physician about the challenges of navigating post-assault health service referral options and judicial remedies for adolescent survivors of gender-based violence (GBV) in rural communities in eastern Bolivia. We examine the protections outlined in various international, regional, and national laws; discuss relevant legal instruments and policies that aim to safeguard the sexual and reproductive health rights of adolescents; and outline mechanisms for their enforcement. We then apply the availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality framework to analyze the extent to which post-assault health services and judicial remedies for adolescent survivors of GBV are sufficient, equitable, and effective. Through our application of this framework, we observe that many adolescent survivors likely experience re-victimization and re-traumatization as they navigate a fragmented patchwork of resources following their victimization. Based on this analysis, we argue for the integration of a human rights framework in designing, implementing, and evaluating post-assault care for adolescent survivors of GBV. We also contend that the 2023 ruling by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in Angulo Losada v. Bolivia sets a legal precedent for holding Bolivia accountable for ensuring that adolescent victims of GBV experience their human and constitutional rights in rural, resource-variable communities in Bolivia.

Introduction

Early one morning in December 2022, Dr. Rojas (pseudonym), a pediatrician in Montero, a peri-urban town in eastern Bolivia, received a WhatsApp message from Fernanda (pseudonym), a 15-year-old girl from a nearby rural community. Fernanda had recently participated in an educational program sponsored by a nongovernmental organization (NGO) that sought to equip adolescents with sexual and reproductive health knowledge (e.g., awareness of their sexual and reproductive health rights, information about menstruation and puberty) and skills (e.g., how to correctly put on a condom, how to ask for consent and establish boundaries).

The program was developed in response to growing concerns from parents about the lack of sexual and reproductive health education in schools, the alarmingly high rates of gender-based violence (GBV), and the increased incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the region.[1] At the program’s inception in 2019, Bolivia had no universal, state-run comprehensive sexuality education in public schools.[2] At the time, the NGO-sponsored program was the only source of formal education that young people in the region would receive about sexual and reproductive health and rights. The program included 10 half-day sessions for 20 adolescent girls in rural communities surrounding the peri-urban town where the NGO’s main office was located. The program was co-developed by a group of student researchers at a university in the United States and Bolivian clinicians, community health workers, and NGO staff. Dr. Rojas was designated as the contact for program participants.

“I have a few bumps down there,” Fernanda’s message read.

“Can you come in today?,” Dr. Rojas replied.

Fernanda “liked” the message.

Upon Fernanda’s arrival, Dr. Rojas escorted her to a makeshift exam room for a pelvic exam. Dr. Rojas documented pelvic pain and signs of genitourinary trauma, including vaginal abrasions, inflammation of the vaginal canal, and ulcerations of the vaginal mucosa. Dr. Rojas summarized that the clinical findings were consistent with a recent traumatic event as well as previous injuries. Dr. Rojas ordered an STI panel and a pregnancy test. Based on Fernanda’s clinical presentation, Dr. Rojas suspected that Fernanda had been the victim of multiple sexual assaults and required both acute and ongoing physical and mental health care, in addition to legal support and other advocacy services.

Dr. Rojas asked Fernanda about her current boyfriend and living situation, reassuring her that she was a safe and supportive person Fernanda could talk to about any situation she may be experiencing. Although Fernanda denied experiencing any abuse or violence, Dr. Rojas remained concerned because the presence of genitourinary trauma was clinically inconsistent with Fernanda’s explanation, suggesting the possibility of undisclosed sexual violence or abuse.

Dr. Rojas referred Fernanda to the primary-level health facility for follow-up care so that Fernanda could receive a consultation with the doctor responsible for the area. Fernanda later informed Dr. Rojas that she went to the appointment with her mother and received medical treatment for an STI. While Dr. Rojas was relieved that Fernanda received care for her injuries, she was concerned that Fernanda did not access care sooner and that she would not have access to specialized health services if her suspicion of violence was correct.

Dr. Rojas was well aware of the reasons why Fernanda might not choose to disclose that she had been the victim of GBV. For instance, even if Fernanda had disclosed to Dr. Rojas that she was a victim of violence, her registration with the Sistema Único de Salud—Bolivia’s universal health insurance program—was not in the municipality of Montero, where Dr. Rojas was based, but in another municipality. As a result, Dr. Rojas needed to first refer Fernanda to the primary health facility nearest to Fernanda’s home—about halfway between Fernanda’s community and Montero—to receive care. Dr. Rojas later remarked that this bureaucratic barrier was the reason many survivors forgo reporting violence. She elaborated that in her 20 years of experience working in rural communities surrounding Montero, many survivors fear that if they go to the health center nearest to their community, their privacy and confidentiality will not be protected. Dr. Rojas commented that many survivors fear potential retaliation from their aggressor.

Dr. Rojas also noted that many survivors in the rural communities she serves face significant barriers to obtaining specialized and trauma-informed medical care, health advocacy, and legal services at the local public hospital and defensoría (public defender’s office). She noted that these barriers may include transportation issues and additional costs associated with services (e.g., printing and notarizing necessary forms). Dr. Rojas explained that the only other referral option was to an NGO that provides temporary emergency shelter, as well as legal and health services, located 130 kilometers from Fernanda’s home in the larger metropolitan city of Santa Cruz. She noted that this option was impossible for many of her patients due to the prohibitive amount of time and money needed to travel to Santa Cruz.

Dr. Rojas’s reflection on the barriers faced by adolescents affected by sexual violence in the region highlights some of the limitations of primary prevention programming—such as the NGO-provided sexual and reproductive health educational intervention—in preventing GBV victimization among adolescent girls. Her testimony about the challenges in providing accessible post-assault referrals for survivors is particularly alarming given the pervasive GBV throughout the country. Throughout this paper, we use the term “post-assault” to refer to a range of experiences that follow an incident of GBV. We intentionally use the term “assault” and not “rape” to reflect the various forms of harmful and traumatic sexual violence that a survivor may endure but that may not meet the legal definition of rape in Bolivia.

National and regional trends in gender-based violence

Bolivia has one of the highest rates of GBV in Latin America.[3] Seventy percent of Bolivian women experience sexual or physical violence, and nearly one-third of adolescent girls suffer sexual violence before the age of 18.[4] Bolivia also has one of the lowest reporting rates of GBV in Latin America due to issues such as “re-victimization, delays in prosecution, and unwillingness by police to cooperate with the justice system.”[5] Additionally, as reported by human rights organizations, the low reporting rates can be attributed to the “justice system’s practice of granting perpetrators of sexual violence impunity for their crimes, especially when committed against underage girls.”[6]

These testimonies and national statistics reflect findings from a recent observational study conducted in two rural communities outside Montero, located in the Obispo Santistevan Province of the Santa Cruz Department.[7] A total of 51.5% (N=104) of adolescent girls and adult women aged 15–35 reported being personally impacted by sexual or physical violence.[8] Among these participants, 72% (N=70) disclosed having been survivors.[9] Only 13 individuals who reported victimization indicated that they had attempted to seek post-assault medical care or legal support. Qualitative results from open-ended survey questions revealed that many survivors refrained from seeking care due to shame, fear of retaliation, the belief that their injuries were not that severe, and the (in)visible costs associated with the services (e.g., transportation).[10] These qualitative findings align with technical reports and other gray literature in the region and are further explored in a later section.[11]

These testimonies underscore the urgent need to critically analyze and document Bolivia’s stated human rights positions regarding the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents, particularly those in rural areas, and how these positions align with or diverge from the lived experiences of adolescents in these communities. The examples presented in this introduction set the stage for a deeper analysis and discussion of the legal protections and rights that are theoretically designed to support and safeguard individuals who are survivors of GBV. While these examples are specific to Dr. Rojas’s experience in assisting adolescents in rural areas outside Montero with referral options, they illustrate challenges that other clinicians may also encounter when providing referrals for adolescent survivors of GBV in various rural settings across Bolivia, as well as for survivors over the age of 18.

Human rights framework

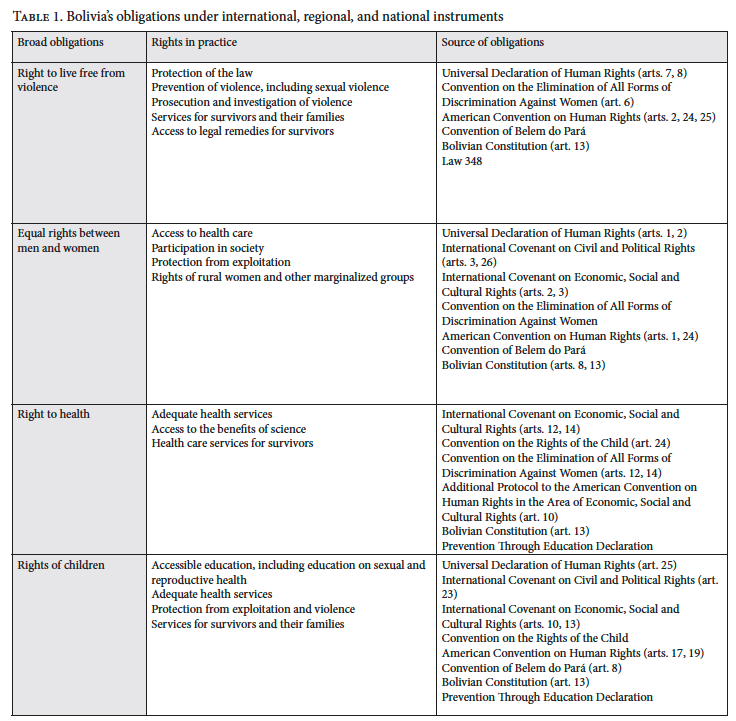

The current Bolivian Constitution was adopted in 2009 after work by then-President Evo Morales to reform the Constitution to “end social injustice and inequality.”[12] The Constitution states that Bolivia is “based on the values of unity, equality, inclusion, dignity, liberty, solidarity, reciprocity, respect, interdependence, harmony, transparency, equilibrium, equality of opportunity, social and gender equality in participation, common welfare, responsibility, social justice, distribution and redistribution of the social wealth and assets for wellbeing.”[13] The Constitution incorporates fundamental rights and invokes the hierarchical dominance of the international and regional agreements and treaties to which Bolivia is a party.[14] In this way, the human rights instruments that Bolivia is a party to take precedence over domestic law, and the Constitution should be interpreted in accordance with international and regional human rights treaties.[15] This is significant because it places Bolivia at a higher level of rights obligations than other states that have not constitutionalized the same international and regional legal norms (see Table 1).

International human rights treaties

Bolivia is a signatory—meaning that it is legally bound—to several international human rights instruments that contain protections prohibiting violence against women and girls. Signatories commit to providing health care, policing, and justice for their citizens, including those harmed by sexual violence.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights are broad multilateral human rights instruments to which Bolivia is a party. These three formative human rights mechanisms obligate signatories to nondiscrimination and the protection of all citizens, including freedom from violence such as GBV.[16]

The Convention on the Rights of the Child—another treaty to which Bolivia is a party—requires states to “protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse” and to provide services to ensure investigation, treatment, and other care for cases of suspected violence.[17] The convention also requires states to adhere to standards set by competent authorities to provide safety and health services.[18] It recognizes the rights of the child concerning health care, including preventative care, explicitly requiring states to develop preventative care as well as “family planning education and services.”[19]

As a signatory of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, Bolivia is required to eliminate discrimination against women and girls in all sectors.[20] The convention promotes equal rights for women and girls and commits parties to “take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in the field of healthcare to ensure … access to healthcare services, including those related to family planning,” and to “take all appropriate measures … to suppress all forms of trafficking in women and exploitation of prostitution of women.”[21] Notably, the convention also provides protections for rural women, specifically ensuring the right of rural women “to have access to adequate health care facilities.”[22]

The international treaties to which Bolivia is a party enforce the Bolivian government’s obligations to ensure that its citizens enjoy the right to live free from violence (including GBV), the right to health, equal rights regardless of one’s gender or status, and rights for children

Regional human rights treaties

Regionally, Bolivia is a party to the American Convention on Human Rights; the Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights in the Area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence Against Women (also known as the Convention of Belem do Pará); and regional measures coordinated through the United Nations, such as the Preventing Through Education Declaration. The Additional Protocol to the American Convention explicitly recognizes the right to health, specifying states’ duty to provide their citizens with primary health care as well as programs to meet the “health needs of the highest risk groups” and the impoverished.[23] Adolescents and victims of GBV are considered to be a high-risk group. These two groups often have a disproportionate burden of STIs, among other sexual and reproductive health issues.[24]

The Convention of Belem do Pará affirms that “violence against women constitutes a violation of their human rights and fundamental freedoms, and impairs or nullifies the observance, enjoyment, and exercise of such rights and freedoms” and thus seeks to address that violence.[25] It defines violence as any act, in public or private, that “causes death or physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women.”[26] The convention specifically requires states to take measures to prevent violence and establish legal procedures for remedy.[27] States that have signed the Convention of Belem do Pará agree to provide services to women affected by violence, including sexual violence, and to those impacted by violence, such as their children or witnesses to violence.[28]

In 2009, the same year Bolivia adopted its new Constitution, health ministers from 30 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, including Bolivia, adopted the Preventing Through Education Declaration, pledging to provide comprehensive sexuality education and sexual health programs.[29] These regional commitments that Bolivia has made regarding human rights, the prevention of violence, and the provision of comprehensive sexuality education and sexual health programs compound upon the obligations it has as a signatory to international human rights instruments.

Bolivian progress on obligations

According to Bolivia’s Constitution, the government must provide comprehensive health care (article 18) and prevent sexual and gender-based violence (article 15), including by ensuring the sexual and reproductive health rights of rural women and ensuring the rights of youth.

In 1997, the Bolivian government established the Ombudsman’s Office (Defensoría del Pueblo), which is tasked with protecting the human rights of Bolivian citizens.[30] The office investigates allegations and complaints of human rights abuses, advocates for individuals whose rights have been violated, and works to improve the legal and institutional framework to better protect human rights across Bolivia.[31] This office has a specialized unit for the defense of children and adolescents (Defensoría de la Niñez y Adolescencia) that provides legal and social support, intervenes in cases of abuse or neglect, and ensures that children’s and adolescents’ rights are upheld in various contexts.[32]

In 2013, Bolivia passed a law to guarantee women a life free of violence (Law 348), which also enumerated Bolivia’s obligations to provide timely comprehensive health and advocacy services for survivors of GBV, ensure access to judicial remedies for survivors of GBV, and furthered the government’s obligations to prevent sexual violence. Law 348 also created a government agency tasked with the prevention, investigation, and apprehension of those responsible for acts of violence against women.[33]

In its 2019 report to the United Nations Human Rights Council in preparation for its Universal Periodic Review, Bolivia highlighted its laws and processes for addressing GBV and ensuring women’s rights.[34] The report highlighted that Bolivia has “consolidated its regulatory and institutional framework to promote equality and to eradicate violence based on gender and sexual orientation.”[35] The report further noted that Bolivia has several government offices and officials focused on combating violence against women, including the Special Office for Combating Violence Against Women, the Plurinational Service for Women and for Dismantling the Patriarchy, the Anti-Violence Squad, the Plurinational Victim Assistance Service, and the Prosecutor’s Office for Victims in Need of Priority Care.[36]

Nonetheless, a 2024 report by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights recognizes that there is a current lack of enforcement in Bolivia on women’s right to a life free from violence.[37] The commission views the lack of accountability for GBV as a symptom of the lack of judicial capacity and lack of public trust in a judicial system that has previously been used for political ends.[38] The authors of the report contend that without further developing the mechanisms for achieving these obligations, it is unlikely that Bolivia can ensure access to remedies for survivors of GBV.

Indeed, in 2023, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued a ruling stating that Bolivia failed to address sexual violence toward Brisa de Angulo Losada, an adolescent girl in Cochabamba.[39] The court concluded that Brisa’s rights to “humane treatment, judicial guarantees, private and family life, equality before the law, judicial protection and children’s rights” were violated due to

the breach of the duty of enhanced due diligence and special protection to investigate the sexual violence suffered by Brisa, the absence of a gender and children’s perspective in the conduct of the criminal process and the re-victimizing practices during that process, of the application of criminal legislation incompatible with the American Convention, as well as institutional violence and discrimination in access to justice suffered by the victim due to her gender and status as a child and the violation of the guarantee of a reasonable timeframe.[40]

This ruling is significant because it establishes an important legal precedent for holding states accountable for systemic failures in addressing GBV and for providing timely, trauma-informed, and culturally responsive judicial remedies for adolescent survivors of GBV. It also provides a legal framework for analyzing gaps in the implementation of state obligations, including gaps in the continuum of services and in the provision and accessibility of specialized health care, advocacy services, and judicial remedies for survivors of GBV.[41]

Our search of both the case name (“Angulo Losada v. Bolivia”) and relevant keywords (e.g., “Angulo” and “Losada” separately) across six databases (Lexis+, Westlaw, vLex, Oxford Reports on International Law, WorldLII, and HeinOnline) revealed that as of April 2025 the Inter-American Court of Human Rights’ ruling had not been used as legal precedent in other national or international cases. However, legislative reform is currently underway in Bolivia to comply with the court’s ruling, which—in addition to ordering the government to pay reparations to Brisa, to “maintain the criminal complaint against the E.G.A [the perpetrator],” and to “determine the possible responsibility of the officials whose actions contributed to the commission of acts of re-victimization and possible procedural irregularities to Brisa’s detriment”—ordered the Bolivian government to

adapt its protocols or adopt new protocols, implement, supervise, and oversee a protocol for investigation and action during criminal proceedings for cases of children and adolescents who are victims of sexual violence, a protocol on a comprehensive approach and legal medical evaluation for cases of children and adolescents who are victims of sexual violence and a comprehensive care protocol for children and adolescents who are victims of sexual violence, and … to implement a campaign to raise awareness, aimed at the Bolivian population in general, aimed at confronting sociocultural perceptions that normalize or trivialize incest.[42]

The proposed legislation also “establishes a series of preventive and access-to-justice measures, including training for prosecutors, forensic doctors, investigators, and judges, who must be provided with specific protocols for caring for underage victims.”[43]

Rights-based approach to health services and judicial remedies for survivors of gender-based violence

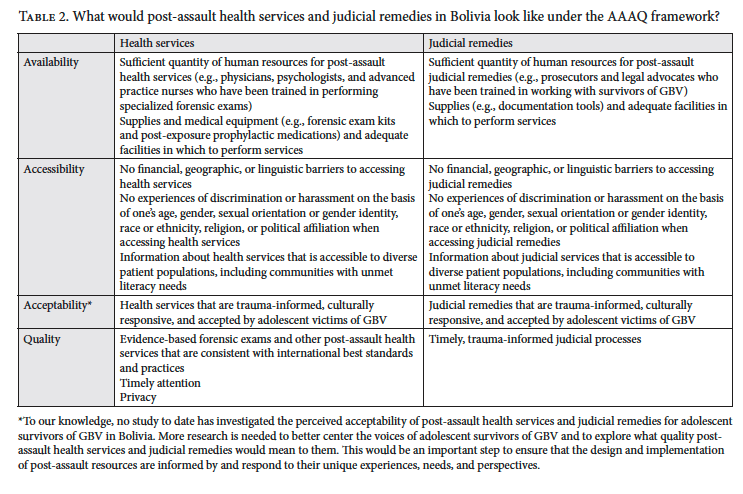

In this section, drawing on the perspective of Dr. Rojas and supported by evidence from other sources, we employ a rights-based approach and utilize the availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality (AAAQ) framework (see Table 2) proposed by the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights to examine the gaps in access to timely and dignified post-assault health services and judicial remedies for adolescent survivors of GBV.[44] In doing so, we emphasize the need for stronger mechanisms to hold states accountable for ensuring the quality and accessibility of post-assault health services and judicial remedies for survivors in rural communities in eastern Bolivia. We also note areas for future research regarding the availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality of comprehensive post-assault health services and judicial remedies for survivors of GBV.

Availability and accessibility

Availability refers to a health system having a sufficient quantity of services, facilities, and supplies needed to provide care.[45] The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights emphasizes that services must be accessible to all patients regardless of their overlapping social identities—such as gender, sexual orientation, race or ethnicity, and political or religious affiliation—or their ability to pay.[46] Additionally, the committee notes that services must be physically accessible to individuals living in rural or marginalized areas.

To our team’s knowledge, as of April 2025, Casa de la Mujer is the only organization in eastern Bolivia providing free, comprehensive, trauma-informed, and specialized medical and psychological services and legal support for survivors of GBV. Even if Fernanda were to report to Dr. Rojas that she was, in fact, suffering from GBV victimization, Dr. Rojas recognized that there were extremely limited publicly run health care services available to survivors in the rural communities surrounding Montero. Reflecting on these limitations of the public health system in rural communities, Dr. Rojas explained:

They never hire more doctors. They never hire more staff. For example, there aren’t even stretchers in the hospitals. There’s nothing to provide privacy for the patient, no scheduled times when they can be seen. According to the law, we should have availability. There are no medications for the patients—there’s nothing. And the health personnel aren’t trained. There are many places where there’s only one nurse who handles everything. There’s no doctor. So, there’s no staff, no budget, no training, and even if there were training, the communities don’t allow us to talk about sexual health because it is not convenient for them.

Dr. Rojas’s remarks are consistent with the only known study evaluating Bolivia’s universal health care coverage program, called the Single Health System (Sistema Único de Salud).[47] This landmark study found that although access to public health care services increased in the first year of the Single Health System compared to previous years, “human resources are insufficient, spending at the macroeconomic level did not reach recommended levels for universal coverage, and long waiting times, and shortages in medicines and beds, persist.”[48]

Additional prior research also supports Dr. Rojas’s recognition of the extremely limited—if not nonexistent—comprehensive and specialized services for victims of GBV in Bolivia. For instance, the authors of the US State Department’s 2023 report on human rights practices in Bolivia found that although the Bolivian government provides “access to sexual and reproductive health services for survivors of sexual violence, including emergency contraception[,] postexposure prophylaxis [is] not available.”[49]

Moreover, the availability of judicial remedies for survivors of GBV is limited. For example, according to a 2019 report from the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School, significant investigative and judicial barriers exist for victims of femicide, a form of GBV.[50] The report details that “Bolivian police investigators struggle to carry out their work in a thorough and timely manner, and systematic roadblocks, such as a lack of resources, corruption, and bias, can undermine their work.”[51] Additionally, the report outlines that “prohibitive costs, delays, and corruption” create barriers for families of the victim who are seeking justice.[52]

In addition to concerns about availability, Dr. Rojas later reflected that many patients in rural areas likely cannot access Casa de la Mujer’s specialized services due to the high travel costs associated with getting to and from their homes. For instance, the public transit route from Fernanda’s community to Montero, where she first met Dr. Rojas, costs 55 Bolivianos, equivalent to US$8, and takes about two and a half hours for a round trip. A ride to the capital city of Santa Cruz, where Casa de la Mujer’s offices are located, would have been two dollars more, costing 70 Bolivianos and lasting four hours round trip. For reference, the average monthly income in communities surrounding Montero fluctuates between US$150 and US$300 per household.

Transportation barriers have been documented by other medical anthropologists working on sexual and reproductive health issues in the region. For example, Carina Heckert, who has worked with individuals living with HIV in communities surrounding Montero and beyond, notes that these individuals often delay or even abandon seeking health care due to high transportation costs.[53]

Previous research has also documented widespread discrimination against and derogatory language toward persons living with HIV, Indigenous Peoples, Bolivians of African descent, women, and individuals who identify as part of the LGBTQ+ community within the provision of public services, including health care.[54]

Furthermore, the US State Department’s 2023 report on human rights in Bolivia notes that access to post-assault medical services is not equally distributed and that access to such services is “more readily available in urban areas.”[55] The authors of the report also write that “rural areas [lack] access and frequently [rely] on mobile health centers such as those provided by Marie Stopes International.”[56]

Institutional discrimination is also reported in the aforementioned 2019 report on femicide and impunity in Bolivia. The report states that “frequently, inadequately trained judges, prosecutors, and investigators fail to implement the gender-sensitive perspective that Bolivian policies require. Instead, some officials approach their work with a gender bias, engaging in victim blaming and discounting important evidence.”[57] It also notes that Indigenous women who are victims of GBV often experience additional sociocultural and linguistic barriers when attempting to access post-assault judicial remedies.

Acceptability and quality

In addition to concerns about the availability and accessibility of specialized services, Dr. Rojas shared that, in her experience, adolescents often fear that if they seek sexual and reproductive health services in their rural, tight-knit community, their privacy or confidentiality may be compromised. For instance, Dr. Rojas described a scenario that she has seen play out in rural communities like Fernanda’s:

When adolescents go to a pharmacy to buy a condom, they buy it really quickly, and the whole community finds out. “Oh, so-and-so was buying condoms, for this and that reason.” Then her mom finds out, and it becomes a problem. Access in Bolivia is very complicated because, especially in rural areas, everyone knows each other.

Dr. Rojas’s comments are consistent with other research in Bolivia, which has documented adolescents’ concerns about privacy and confidentiality when seeking sexual and reproductive health services.[58] This same research has emphasized the importance of a competent, well-trained, and adolescent-friendly health workforce to assist in increasing adolescents’ health care utilization.

Additionally, inconsistent delivery of post-assault health services throughout the country has been documented.[59] Evidence suggests that public institutions tasked with handling cases of sexual violence fail to do so in a timely way.[60] Additionally, research shows that survivors often experience harassment and discrimination when attempting to access post-assault legal support and medical services and that state institutions fail to coordinate work across agencies effectively.[61] Other research has found that survivors and their families often have to navigate confusing and convoluted paths to health care and legal assistance that exist within a context of hypermasculinity (known in Spanish as machismo) and other forms of discrimination based on gender and sexuality.[62]

Reflecting on her experience navigating post-assault referral options for survivors of GBV in rural communities, Dr. Rojas expressed frustration and deep concern about the systemic neglect of survivors’ care and institutional apathy. She also hinted at the potential for re-victimization and re-traumatization of survivors as they navigate post-assault health services and judicial remedies:

There are no psychologists in the health system. So the girl [a survivor of GBV] decided to trust someone, and now the whole system is against her. There are no psychologists to support her, the police blame her, her parents blame her, and the staff don’t want to deal with that patient anymore because now, because of her, they have to go to court … it’s very problematic and very complicated.

This potential for re-victimization and re-traumatization described by Dr. Rojas is an example of “sanctuary trauma,” a term coined by Steven Silver in the 1980s.[63] Silver used the term to refer to when a patient expects a safe, protective, and supportive environment (e.g., emergency room or police station) but instead experiences only additional stress, trauma, and violence.[64]

Although the concept was originally applied to veterans, “sanctuary trauma” is a useful notion in the context of adolescent survivors of GBV. However, to our knowledge, global health research on post-assault health care and judicial service utilization among survivors of GBV in rural, resource-variable contexts in low- and middle-income countries has not used or applied “sanctuary trauma” as a conceptual or theoretical framework to describe the experiences of survivors as they attempt to access care. Future research ought to apply this framework to examine the ways in which adolescent survivors of GBV may experience trauma as they attempt to access post-assault health care services and judicial remedies.

This review of extant literature about the availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality of post-assault health care services and judicial services, coupled with Dr. Roja’s testimony, reveals that adolescent survivors of GBV may face barriers preventing them from accessing post-assault resources, which in turn could exacerbate trauma and impede healing. This is even though Bolivia is party to several international agreements guaranteeing sexual and reproductive health care and states in its Constitution that all citizens have the right to these health services.

Conclusion

Our analysis reveals that despite the assurances made by Bolivian laws and policies to prevent GBV and support survivors in receiving post-assault care, Bolivia is falling short in its attempt to fulfill these broad obligations. As Dr. Rojas poignantly reflected, in Bolivia, “sexual health exists very wonderfully, but it only exists on paper.” The country has yet to meet its commitments concerning GBV, and the human rights of adolescent survivors remain under threat. Moreover, as we show above, adolescent victims of GBV may be experiencing “sanctuary trauma” in their attempts to access post-assault care.[65]

More research is urgently needed on the delivery of health services and judicial remedies for adolescent survivors of GBV in rural Bolivia. Additionally, there is a need for further investigation into the effects of socio-structural factors (e.g., poverty) on the effectiveness of sexual and reproductive health interventions in resource-variable settings such as rural eastern Bolivia. A better understanding of these factors could inform the development of more targeted and effective policies and interventions.

Lastly, collaboration between NGOs, academic institutions, health care providers, and local communities is essential to address the multifaceted challenges faced by adolescents in accessing sexual and reproductive health services, including post-assault care, and to ensure the fulfillment of sexual and reproductive health rights.

Acknowledgments

This project would not be possible without the tremendous support and effort of our Bolivian colleagues at Etta Projects in Montero, Bolivia: Irene Cortelazzi and Leonardo Braca. Our many community health workers and other local clinicians are also indispensable to our project.

Funding

This research is a part of a larger project at the University of Minnesota titled “Gender-Based Violence and Post-Assault Care in Rural Bolivia.” Funding for project activities was provided by the University of Minnesota’s Center for Global Health and Social Responsibility Seed and Global Engagement Grant Programs to support international research, as well as the university’s School of Nursing Foundation. Law student involvement in the project was made possible through the university’s Human Rights Center. The example analyzed in this research was documented during Voller’s doctoral dissertation fieldwork, which was sponsored by the US Department of State’s Student Fulbright Research program in Bolivia.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (STUDY00020590) and (STUDY00017895) and conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to data collection, informed consent (and assent, where applicable) was obtained from all participants in a language and format they understood. Participants were informed of the voluntary nature of the study, their right to withdraw at any time without penalty, and the measures taken to ensure their confidentiality and privacy. In Bolivia, we also sought institutional- and community-level endorsement for our research. While there is no centralized national institutional review board for nonclinical research in Bolivia, local ethical clearance was obtained through collaboration with municipal health networks and organizational partners. This included sharing study objectives, methods, and intended outcomes with stakeholders and incorporating their input to ensure that the research was culturally appropriate and aligned with the organizational partner’s expectations. A faculty member at the Universidad Autónoma Gabriel René Moreno who is a national expert on sexual and reproductive health and rights and GBV also provided input on Voller’s dissertation design. This dual-approval process—through the University of Minnesota and Bolivian organizational-based review—was designed to honor both formal institutional protocols and the ethical imperative of community-engaged, respectful research practices.

Translation

This paper, including all quotations from cases and other Spanish-language material, was translated from Spanish into English by Vanessa Voller.

Vanessa K. Voller, PhD, MDP, is a scholar at the Center for Global Health and Social Responsibility at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, United States.

Mikaela Smith is a JD candidate at the University of Minnesota Law School, Minneapolis, United States.

Caterine Senzano Castro is a family physician based in Montero, Bolivia.

Gabriella Barrozo is a psychologist based in Santa Cruz, Bolivia.

Fiorella Burgos is the coordinator of public health projects at Etta Projects, Montero, Bolivia.

Dino Maccari, MSc, is the executive director of Etta Projects, Tacoma, United States.

Pennye Nixon, MA, is the founder and associate director of Etta Projects, Montero, Bolivia.

Christie L. Martin, PhD, MPH, RN-BC, is an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota School of Nursing, Minneapolis, United States.

Lucy Mkandawire-Valhmu, PhD, RN, FAAN, is a professor of nursing at the University of Minnesota School of Nursing.

Alex Mysler is a JD candidate at the University of Minnesota Law School, Minneapolis, United States.

Veronica Pellizzari is the director of programs at Etta Projects, Montero, Bolivia.

Sarah J. Hoffman, PhD, MPH, RN, SANE-A, is an associate professor at the University of Minnesota School of Nursing, Minneapolis, United States.

Please address correspondence to Sarah Hoffman. Email: hoff0742@umn.edu.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2025 Voller, Smith, Senzano Castro, Barrozo, Burgos, Maccari, Nixon, Martin, Mkandawire-Valhmu, Mysler, Pellizzari, and Hoffman. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

[1] M. Patzi-Churqui, K. Terrazas-Aranda, J.-Å Liljeqvist, et al., “Prevalence of Viral Sexually Transmitted Infections and HPV High-Risk Genotypes in Women in Rural Communities in the Department of La Paz, Bolivia,” BMC Infectious Diseases 20/1 (2020).

[2] L. Femenía and R. López, Educación integral en sexualidad, prevención de la violencia y despatriarcalización en el colegio (Coordinadora de la Mujer, 2021).

[3] Equality Now, “Sexual Violence Against Adolescent Girls in Bolivia and Its Consequences,” https://equalitynow.org/sexual_violence_against_adolescent_girls_in_bolivia/.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Equality Now, Latin American and Caribbean Committee for the Defense of Women’s Rights, Oficina Jurídica de la Mujer, et al., “Information on Bolivia for the Consideration of the Human Rights Committee at Its 134th Session (February 28 – March 25, 2022),” submission to Human Rights Committee Secretariat (January 31, 2022), para. 13.

[6] Ibid.

[7] S. Hoffman, V. K. Voller, V. Pellizzari, and C. Senzano, “Violencia de género e atención post-agresión en comunidades alrededor de Montero: Resultados preliminaries” (presentation at the Health Network of Santa Cruz Annual Infectious Disease Meeting, Montero, Bolivia, February 2025).

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Plan International Bolivia, The State of Girls’ Rights in Bolivia (2022); Equality Now et al. (see note 5).

[12] ConstitutionNet, “Constitutional History of Bolivia,” https://constitutionnet.org/country/constitutional-history-bolivia.

[13] Constitution of Bolivia (2009), art. 8(II).

[14] Ibid., arts. 13(IV), 410(II).

[15] Ibid.

[16] Universal Declaration of Human Rights, G.A. Res. 217A (III) (1948); International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI) (1966); International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI) (1966).

[17] Convention on the Rights of the Child, G.A. Res 44/25 (1989), art. 19.

[18] Ibid., art. 3(3).

[19] Ibid., art. 24.

[20] Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, G.A. Res. 34/180 (1979).

[21] Ibid., arts. 6, 12.

[22] Ibid., art. 14.

[23] Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights in the Area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (Protocol of San Salvador) (1988), art. 10.

[24] “Youth STIs: An Epidemic Fuelled by Shame,” Lancet Child and Adolescent Health 6/6 (2022).

[25] Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence Against Women (Convention of Belém do Pará) (1994), preamble.

[26] Ibid., art. 1.

[27] Ibid., art. 7.

[28] Ibid., art. 8.

[29] UNAIDS, “Preventing HIV Through Education in Latin America and Caribbean” (July 31, 2009), https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2009/july/20090731edu.

[30] Defensoría del Pueblo, “Historia Defensoria del Pueblo,” https://www.defensoria.gob.bo/contenido/historia-defensoria-del-pueblo.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Bolivia, Ley integral para garantizar a las mujeres una vida libre de violencia, Ley 348 (2013).

[34] Human Rights Council, National Report Submitted in Accordance with Paragraph 5 of the Annex to Human Rights Council Resolution 16/21: Plurinational State of Bolivia, UN Doc. A/HRC/WG.6/34/BOL/1 (2019).

[35] Ibid., para. 53.

[36] Ibid., paras. 99, 100–101, 106, 108.

[37] Organization of American States, Cohesión social: El desafío para la consolidación de la democracia en Bolivia (2024).

[38] Ibid.

[39] Inter-American Court of Human Rights, “Bolivia Is Responsible for Gender and Child Discrimination and Revictimization of an Adolescent Victim of Sexual Violence During the Judicial Process” (January 19, 2023), https://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/comunicados/cp_04_2023_eng.pdf.

[40] Ibid.

[41] R. Celorio, “The New Gender Perspective: The Dawn of Intersectional Autonomy in Women’s Rights,” Chicago Journal of International Law 25/1 (2024); C. S. Westman, “Brisa de Angulo Losada vs Bolivia,” Africa Insight 53/4 (2025).

[42] Comunidad de Derechos Humanos, “A dos años de la sentencia en el caso Ángulo Losada vs. Bolivia: Las modificaciones a los delitos de violencia sexual y otras medidas aún están pendientes” (January 23, 2025), https://comunidad.org.bo/index.php/pronunciamiento/detalle/cod_pronunciamiento/43.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000).

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] G. A. Agafitei, “El Sistema universal de salud boliviano y el acceso efectivo a la atención sanitaria: Un diagnóstico,” Revista Latinoamericana de Desarrollo Económico 21/39 (2023).

[48] Ibid., p. 35.

[49] US Department of State, 2023 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Bolivia (2024), p. 26.

[50] F. Alvelais, I. Pitaro, J. Wenck, and T. Becker, “No Justice for Me”: Femicide and Impunity in Bolivia (Harvard Law School International Human Rights Clinic, 2019).

[51] Ibid., pp. 2–3.

[52] Ibid., p. 3.

[53] C. Heckert, Fault Lines of Care: Gender, HIV, and Global Health in Bolivia (Vanderbilt University Press, 2016).

[54] US Department of State, 2022 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Bolivia (2023); US Department of State (2024, see note 49); B. Gerlach, Does Ethnic Origin Matter for Health Inequalities in Bolivia? An Assessment of the Effect of Ethnicity on Health Care Access and Health Outcomes, master’s thesis (Lund University, 2022); A. Zulawski, Unequal Cures: Public Health and Political Change in Bolivia, 1900–1950 (Duke University Press, 2007).

[55] US Department of State (2024, see note 49), p. 27.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Alvelais et al. (see note 50), p. 3.

[58] L. Jaruseviciene, M. Orozco, M. Ibarra, et al., “Primary Healthcare Providers’ Views on Improving Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare for Adolescents in Bolivia, Ecuador, and Nicaragua,” Global Health Action 6/1 (2013).

[59] Alvelais et al. (see note 50).

[60] Ibid.

[61] Ibid.

[62] US Department of State (2023, see note 54).

[63] S. M. Silver, “An Inpatient Program for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Context as Treatment,” in C. R. Figley (eds), Trauma and Its Wake: Volume II (Brunner/Mazel, 1986).

[64] Ibid.

[65] Silver (see note 63).