Discrimination in Health Care: A Scoping Review of the Ontario Experience

Vol 27/1, 2025, pp. 27-41 PDF

George Drazenovich

Abstract

This scoping review examines systemic and direct health care discrimination in Ontario, Canada, from 2021 to 2024, analyzing claims, contexts, affected groups, interventions, and research gaps. It reviews 23 Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario cases, 11 articles, and 5 gray literature reports. Findings highlight prevalent discrimination claims, including denial of service, denial of entitlement, service removal, and reprisal, which disproportionately affect Indigenous Peoples, racialized groups, and individuals with disabilities. Studies emphasized policy and educational interventions, advocating culturally informed practices and rural resource equity. Following the spirit and intent of human rights law, which is preventative and remedial and not punitive, the review recommends several policy reforms, increased representation of marginalized groups, and mediation to address claims. It urges codifying health care as a constitutional right to ensure an inclusive system meeting Ontario’s diverse needs.

There are many good recommendations from the jury, but they are meaningless if they are not acted on and nothing changes. Nothing can undo what has happened, but the status quo is unacceptable. It is our responsibility to honour Ruthann by ensuring that these recommendations are implemented and make transformative changes in the delivery of health services for our communities so that these tragedies don’t continue to happen.

—Grand Chief Alvin Fiddler on the Coroner’s Inquest into Ruthann Quequish[1]

Ruthann Quequish lived in Kingfisher Lake First Nation, a community in Northwestern Ontario, Canada; at 31 years of age, she died of diabetes-related complications after making several visits to the community’s nursing station.[2] The Office of the Chief Coroner conducted a discretionary inquest to investigate the circumstances surrounding Ruthann’s death. According to Kate Forget, inquest counsel with the Indigenous Justice Division of Ontario’s Ministry of the Attorney General and member of Matachewan First Nation, discretionary inquests are held as a public service to identify systemic issues and arrive at recommendations for, in this context, how the health system can be improved so that more equitable health care can be provided.[3] The inquest provided several constructive recommendations for concrete actions and reforms that various health care groups named in the jury’s findings could implement.[4] Adding to these findings, Grand Chief Alvin Fiddler stated, “Ultimately, it was neglect, racism, and chronic underfunding that killed Ruthann. There is a critical lack of health care services across [Nishnawbe Aski Nation] territory that continues to claim the lives of our members.”[5] Neglect, racism, and chronic underfunding are systemic issues that perpetuate health care discrimination in Ontario. Canadian courts have consistently defined discrimination as differential treatment—intentional or unintentional—that disadvantages individuals or groups based on protected grounds.[6] Protected grounds refer to “age, ancestry, colour, race, citizenship, ethnic origin, place of origin, creed, disability, family status, marital status (including single status), gender identity, gender expression, receipt of public assistance (in housing only), record of offences (in employment only), sex (including pregnancy and breastfeeding), sexual orientation.”[7]

Differential treatment in health care experienced by Indigenous Peoples and other racialized and marginalized groups, globally and in Canada, can constitute a violation of international human rights. This includes article 12(2)(d) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which mandates the progressive realization of health rights.[8] In addition, it may compromise article 25(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a guiding principle for human rights.[9] In Canada, such disparities may violate sections 7 and 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which protect the security of the person and equality.[10] The Supreme Court of Canada, in Chaoulli v. Quebec (Attorney General), interpreted section 7 to include timely access to health care, stating that “access to a waiting list is not access to healthcare.”[11] At the same time, discrimination based on protected grounds directly implicates section 15. Courts assess violations by examining whether the state has taken reasonable and progressive steps to address differential treatment and disparities.

This review aims to analyze health care discrimination in Ontario and support the province in implementing effective solutions in line with human rights obligations regarding health care. Canadian legal scholars suggest that the equality rights framework of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms should address systemic disadvantages, including barriers to health care access, as a matter of constitutional protection.[12] Groups such as the Wellesley Institute recommend codifying the right to health care in domestic law, including constitutional protections, to align with Canada’s international obligations.[13]

Building on previous scoping reviews by Sarah Hamed et al. and Sibille Merz et al. on health care discrimination in other jurisdictions but focusing on the Ontario experience, this review aims to (1) determine the context of discrimination claims (e.g., denial of entitlement, denial of service, removal of service, reprisal); (2) summarize what kind of discrimination claims (direct or systemic) are being made; (3) identify which groups are most represented in discrimination claims and studies; (4) describe what is currently being done or what recommendations are being made to address the issue; and (5) identify further remedies, including rights-based ones, to better prevent discrimination from arising.[14]

Rationale

While Canadians value the public health care system, they, along with 92% of physicians, agree that it requires significant reform, according to a survey commissioned by the Canadian Medical Association.[15] When asked for focus areas for reform, survey respondents identified timely access, equity, and sufficient supplies and support for health care professionals. Additionally, discrimination in Canadian health care is linked to adverse health outcomes, such as unmet care needs among Indigenous and other racialized groups, including Black and South Asian populations, underscoring the urgency of reform.[16] Discrimination has tangible health consequences. For instance, Jude Mary Cénat found that 32.55% of Black participants experienced significant discrimination, linked to lower COVID-19 vaccination rates and higher anxiety.[17] Similarly, Wanda Phillips-Beck et al. reported a 5.2 odds ratio of unmet health care needs for Indigenous People facing racism, deterring care-seeking.[18] To better grasp the scope of discrimination in the Canadian health care system, it is essential to situate the review within Ontario’s context. This is due to the unique features of Canada’s health care system.

Canadian health care context

As Danielle Martin et al. explain in The Lancet, the Canadian health care system “is less a truly national system than a decentralized collection of provincial and territorial insurance plans covering a narrow basket of services, which are free at the point of care. Administration and service delivery are highly decentralized, although coverage is portable across the country.”[19] The Canada Health Act provides the framework for how the public health care system in Canada is funded and operationalized, including which jurisdiction (federal, provincial, or territorial) has responsibility for which areas.[20]

Thus, when reviewing the scope of discrimination in the health care system, it is important to study provincial jurisdictions specifically, as provincial governments bear the brunt of responsibility for delivering services to the people of any given province. Canadian provinces maintain a great deal of authority and responsibility regarding health services. However, national ethics and the Canada Health Act still bind provinces together regarding the maintenance of a publicly funded and accessible health care system.

Consequently, in Canada, health care is considered a public service, protected and guided by federal law but delivered by provinces. The Ontario Human Rights Code protects vulnerable people according to what is referred to in the code as protected grounds and in what is referred to as protected areas, including health care.[21] Human rights legislation aims to prevent discrimination from occurring in the first place and, where it is found to have occurred, provide remedies that can, to the extent possible, bring the person back to wholeness and restore any rights that may have been violated.[22]

This review approaches discrimination in health care according to the spirit and intent of human rights law, which is preventative and remedial, not punitive. Therefore, the primary interest of this scoping review is to discover common themes regarding instances of direct or systemic discrimination in Ontario; find out what actions health care services are currently taking to prevent discrimination; and summarize the literature’s recommendations for how the health care system can build a more inclusive and responsive approach to the needs of diverse groups.

Materials and methods

This scoping review analyzed claims and reports of health care discrimination by reviewing empirical qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies on discrimination in Ontario and findings from the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario (HRTO).

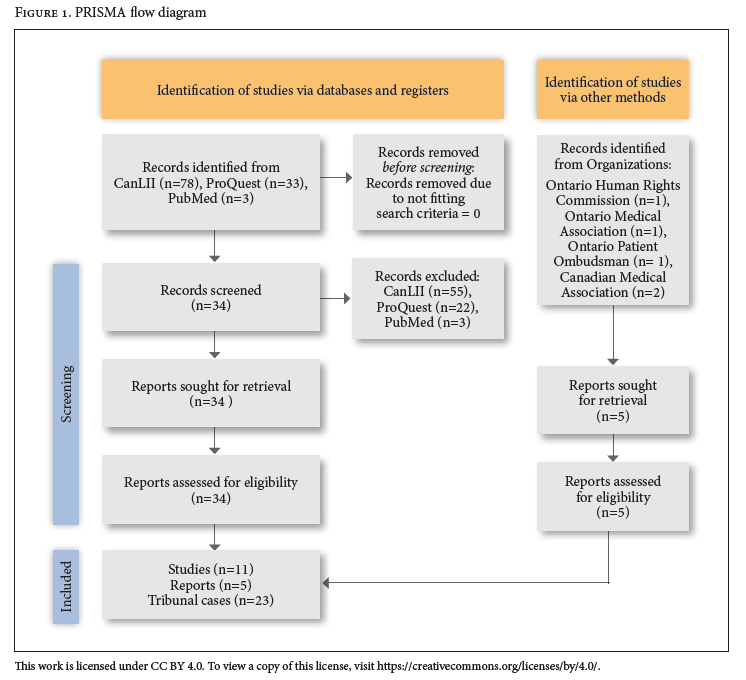

The review sought to determine what kind of discrimination claims are being made, to which protected group people belong (referred to in human rights law as the protected ground), and what orders or recommendations are being made to address the issue(s) (referred to in human rights law as remedies). The review was based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews, which supports transparency and objectivity.[23]

Search strategy

Time frame. To better manage volume and content and to cover, at least in part, the pre- and post-pandemic period during which specific claims were made regarding COVID-19 restrictions or mandates, I applied a time frame of three years (2021–2024). COVID-19-related cases emerged organically from the data due to public health interventions. Additionally, this time frame tracks with that of the published scoping review of Hamed et al. and Merz et al., making comparisons and synergies between these more relevant.[24]

Databases. I used several databases. CanLII (a public database of Canadian legislation and court rulings) was utilized to identify HRTO cases.[25] ProQuest and PubMed were used to identify peer-reviewed studies. A search using Microsoft’s AI Copilot was used to access reports from prominent bodies responsible for delivering reports of discrimination and improving the health care system. These bodies include the Canadian Medical Association, the Ontario Medical Association, the Patient Ombudsman of Ontario, and the Ontario Human Rights Commission.

Search terms. For the literature review, I used the search terms “discrimination,” “healthcare,” “Ontario,” “equity,” and “rights” to capture health care discussions within a human rights framework, based on discussions with academic supervisors and consultation with previous reviews, notably Merz et al. and Hamed et al. For the HRTO cases, I used the search terms “discrimination,” “health,” “care,” “rights,” “access,” and “decision”; I excluded “equity” because it is not a standard legal term in tribunal jurisdiction. I did not use “COVID” as a search term because the focus was on discrimination broadly, not pandemic-specific issues, although these issues, among others, arose during this period. A brief subsection in the discussion further contextualizes COVID-19’s relevance to the review.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria. I included only those subjects pertaining to discrimination in health care in the province of Ontario between 2021 and 2024. Excluded articles include those with no nexus with the issue of discrimination in health care, as described above. HRTO records that were process-oriented and administrative, such as a decision on publication bans without reference to the substance of the case, were excluded. Finally, peer-reviewed articles were excluded if the study had no nexus with a health care setting, system, or service.

Data extraction. I extracted all records, reports, and judicial findings from the aforementioned databases and websites.

The CanLII database yielded 78 results. After conducting a review of all of these cases, I excluded 55 of these because they did not meet the abovementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. This left me with a total of 23 HRTO cases.

The ProQuest search yielded 33 studies. After screening the records’ content and reports for adherence to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, I selected 11 studies. As with the CanLII search, some of the articles lacked a nexus with an identified health care setting, although they focused on the experience of racialized and other protected groups. The PubMed search yielded three studies, but I excluded all of them because they did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

For the gray literature search, the Ontario Human Rights Commission website yielded one report that fell within the search criteria; the Ontario Medical Association yielded one; the Ontario Patient Ombudsman yielded one; and the Canadian Medical Association yielded two.

In total, 119 records were identified, with 39 retained: 23 HRTO cases, 11 studies, and 5 reports. Figure 1 provides a PRISMA flow diagram for the scoping review process.

Results

This section presents findings from the HRTO cases, empirical studies, and gray literature, organized into subsections for clarity.

Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario cases

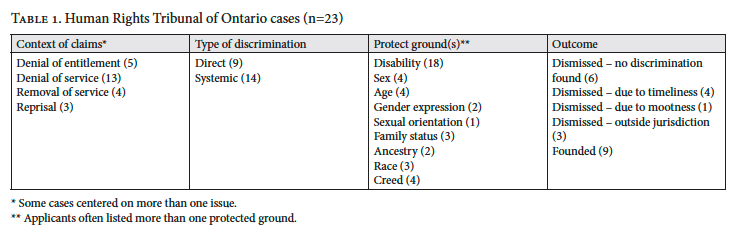

Table 1 summarizes the 23 HRTO cases by claim context, type of discrimination claim, protected grounds, and outcomes. Claims centered on the denial of entitlement (5), denial of service (13), removal of service (4), and reprisal (3), with 9 claims of direct discrimination and 14 claims of systemic discrimination. Disability (18) was the most cited ground, followed by sex (4), age (4), and others. Outcomes showed 9 cases founded, with others dismissed due to no finding of discrimination (6), timeliness (4), mootness (1), or jurisdiction (3). Jurisdictional limits often arose where clinical decisions were outside the HRTO’s scope.

An example of denial of entitlement is A.H. v. Ontario (Children, Community and Social Services).[26] In that case, the applicant, A.H., claimed that policy limitations set by the Ontario Autism Program limited A.H.’s access to the level and range of programming recommended by their treating professionals. Thus, in this instance, the respondent was the government organization responsible for providing those entitlements. A.H. claimed that the provincial government agency interpreted the policy in a way that discriminated against them, denying A.H. this program entitlement.

An example of denial of service is Beckford v. Ontario (Solicitor General).[27] In that case, Beckford claimed that the staff in the custodial facility to which he was sentenced placed him in a segregation unit, fully aware of his medical conditions and that such an act would exacerbate them. In so doing, Beckford claimed, the custodial facility denied him service.

An example of the removal of service is Pankoff Estate v. The Corporation of the City of St. Thomas.[28] The Pankoff Estate claimed that the long-term care facility discharged their family member after she was transported to the hospital due to issues associated with dementia. That experience was categorized as a removal of service.

As an example of reprisal, in Fife v. Sienna Senior Living Inc., the applicant claimed that they were “reprised against by limits in visiting time when their mother was in palliative care and by the lack of quality care provided by the respondent facility and its staff” due to complaints the applicant made about their mother’s care.[29] In human rights law, a service or person cannot take punitive action against someone or their family because they raise a discrimination claim. In Fife, the adjudicator wrote:

As the Tribunal set out in Noble v. York University …, in an allegation of reprisal, the following elements must be established: a. An action taken against, or threat made to the applicant; b. The alleged action or threat is related to the applicant having claimed or attempted to enforce a right under the [Ontario Human Rights Code]; and c. An intention on the part of the respondent to retaliate for the claim or attempt to enforce the right.[30]

After reviewing all 23 cases, I classified each one according to the type of discrimination being alleged: direct or systemic. This distinction was based on whether the discriminatory issue was a policy (categorized as systemic) or action that someone took (categorized as direct). As discussed further below, most cases cannot easily be classed as systemic or direct because they intersect. Interpretation and application of a policy drives a behavior, and vice versa. Nonetheless, these distinctions are useful when considering remedies. For systemic-oriented issues, policy or procedure changes can be made, while for direct cases, training can be provided to prevent similar situations from arising again or to provide compensation to the applicant to remedy injury to them as a result of the violation of their rights. For example, in Powell v. Ontario (Solicitor General), the adjudicator found that discrimination occurred when the police failed to accommodate Powell’s disability when she was in custody.[31] As a remedy, in addition to the respondent paying the applicant C$2,000 in compensation for injury to dignity, feelings, and self-respect, the tribunal stated that the facility needed to “retain an external consultant, with human rights experience, to conduct a review of its policies, procedures, and protocols which relate to the screening of individuals when entering into custody, to ensure that they comply with the Code and in particular the recognition and treatment of persons with diabetes in their custody.”[32] In this way, the systemic change in procedure may change the direct practice moving forward. Systemic reforms can therefore have a direct effect.

The claim of protected ground is self-explanatory. People can and do list several protected grounds that they believe are factors in their discrimination (e.g., disability, age, race). The adjudicator goes through these grounds to find evidence to support the claim. One of the limitations of the traditional system of an adjudicator selecting just one ground and conducting analysis on that ground is that it ignores the reality that multiple grounds of discrimination intersect. People often belong to several protected grounds simultaneously, and it is not easy to discern which specific ground was a factor in discrimination. This reality is reflected in many of the cases reviewed.

Finally, I looked at the outcome of each case. In particular, I analyzed the basis for dismissal in the 14 cases that were dismissed, as this is important for understanding the limitations in making claims before the HRTO and finding or creating alternative pathways for resolution. Frequently, adjudicators cite jurisdictional issues for why they need to dismiss a case. For example, in Parratt v. Lakeridge Health, the applicant alleged that they were discriminated against in the health facility due to a mental health disability when the facility used restraints on them and made other clinical decisions in the context of providing emergency medical care.[33] The adjudicator found that it was outside of the HRTO’s jurisdiction because clinical decisions, even if later found to be incorrect, are outside the scope of the court’s adjudication. In arriving at their decision, the adjudicator—as many adjudicators did in the reviewed cases—drew on Moshi v. Ontario (Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services). In Moshi, the HRTO found that

The Tribunal has no jurisdiction to review a physician’s clinical decisions based on whether or not they were medically appropriate: Kline v. Ontario (Community Safety and Correctional Services) …; Canada Health Act v. London Health Sciences Centre … An applicant cannot establish that a physician, for example, discriminated against him or her merely by showing that the doctor made a clinical decision based on the applicant’s disability, which clinical decision turned out to be disadvantageous for the applicant. Doctors may make sound clinical decisions that end up compromising their patient’s health, for some reason. They can also make mistakes that have adverse medical consequences for their patients. However, neither of these situations constitutes discriminatory treatment under the [Ontario Human Rights Code] … To establish that a physician, for example, has discriminated against someone “because of” disability, an applicant would have to establish that there was some arbitrariness in the manner the physician treated him because of his disability. As the Supreme Court emphasized in McGill University Health Centre (Montreal General Hospital) v. Syndicat des employés de l’Hôpital général de Montréal … the essence of discrimination is in the arbitrariness of its negative impact.[34]

The period of this scoping review covered the COVID-19 pandemic, when masking and vaccines were prescribed by law. Interestingly, the protected grounds of cases that challenged vaccine mandates were frequently cited as creed and largely dismissed as outside of HRTO jurisdiction. For example, in Oulds v. Bluewater Health, in response to the mandatory vaccine requirement, the applicant stated to the respondent, a hospital requiring mandatory vaccinations:

I am fully vaccinated with all the childhood vaccine requirements and my adult boosters are up to date. I am not against medical advancements. I would require more information before taking any treatment that has not been thoroughly identified or tested. I have a conscience given to me by my Creator. That God conscience I access through prayer and meditation. This forms part of my connection to my Creator. Upon accessing that conscience, I am simply told by my Creator “no” in regard to this mandatory vaccination.[35]

The respondent refused to accommodate on those grounds, stating, “Given that you have received previous vaccinations, these personal beliefs do not preclude you from being vaccinated. Moreover, even if the Hospital is wrong in its assessment of your creed beliefs, the Hospital is unable to accommodate your request to be exempt from the application of the policy.”[36]

The adjudicator noted that courts have struggled with the ground of creed, stating:

The [Ontario Human Rights Code] itself does not define creed … In an effort to assist with an understanding of what creed refers to, the Ontario Human Rights Commission enacted a policy recommending that the following characteristics are relevant when determining if a belief system is a creed under the Code. A creed: Is sincerely, freely and deeply held; Is integrally linked to a person’s identity, self-definition and fulfilment; Is a particular and comprehensive, overarching system of belief that governs one’s conduct and practices; Addresses ultimate questions of human existence, including ideas about life, purpose, death, and the existence or non-existence of a Creator and/or a higher or different order of existence; Has some nexus or connection to an organization or community that professes a shared system of belief … I agree with and adopt the policy of the Commission. I note that a different adjudicator at this Tribunal has very recently upheld this definition of creed in Yeomans v. Superette.[37]

The adjudicator dismissed the application, writing that while they accepted that the applicant’s belief was sincerely and deeply held and that it may even be linked to their self-identity and self-definition, there was no additional basis upon which they could determine that it meets the other criteria to be considered a creed:

If the submissions had included some examples about other life-guiding beliefs arrived at through dialogue with the Creator, or about other “alterations” to the body that they similarly reject on the same grounds, then perhaps there could be connection to a particular and comprehensive, overarching system of belief …What is left seems focused on a singular belief around the lack of efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine and some perception that the vaccine could alter DNA, and the need for autonomy to make this specific vaccine choice. In the circumstances of this case, I find that the applicant has not demonstrated that “bodily autonomy”, including the personal choice not to vaccinate, even if the applicant has a sincerely held belief that it was dictated by a Creator, comes within the meaning of creed under the Code.[38]

Consequently, the application was dismissed as being outside of the jurisdiction of the HRTO. The role of the HRTO is not to evaluate public health interventions but to assess for discrimination and, where it is found, apply remedies. In this case, the HRTO did not find that the ground of creed was satisfied—and that consideration, not the vaccine mandates, was the issue before it.

Empirical studies

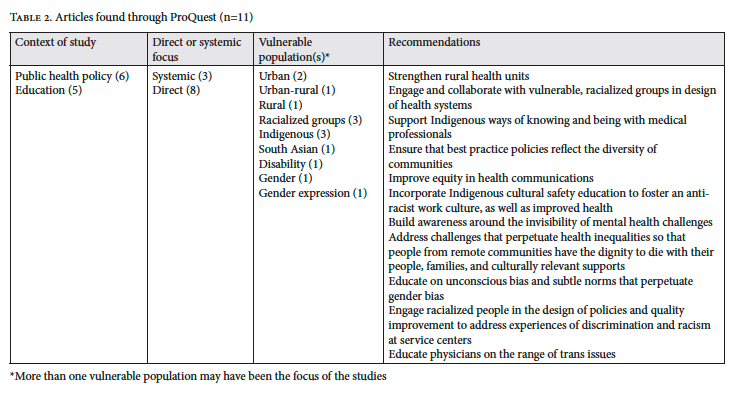

Table 2 summarizes the 11 articles found on ProQuest by study context, focus (direct or systemic), population, and recommendations. Contexts were public health policy (6) and education (5), with 3 systemic and 8 direct focuses. Vulnerable populations included Indigenous populations (3), racialized groups (3), and others. Recommendations ranged from strengthening rural health units to incorporating Indigenous cultural safety education. For instance, Ana Paula Belon et al. noted rurality as a vulnerability, suggesting equitable resource allocation.[39] Javiera-Violeta Durán Kairies et al. found that land-based education improved professionals’ equity awareness for Indigenous care.[40]

After a review of the literature, I identified two main contexts of the studies: public health policy and education. Regarding policy, Belon et al. focus their review on inequities across public health units in Ontario.[41] As they write, “Public health units (PHUs), the regional public health bodies, are now required to address health equity through four requirements: (a) Assessing and Reporting; (b) Modifying and Orienting Public Health Interventions; (c) Engaging in Multi-sectoral Collaboration; and (d) Health Equity Analysis, Policy Development, and Advancing Healthy Public Policies.” They were interested in how these reporting frameworks, one domain involving health equity analysis, were being implemented. The focus of their work, therefore, was systemic.

Interestingly, they identified rural communities as a vulnerable population and recommended that resources be directed equitably to support rural public health groups in their efforts to analyze health equity in their jurisdictions. Rurality is not a protected ground that people can claim under the Ontario Human Rights Code, but it is an issue discussed in the literature on human rights. Amanda Lyons writes:

Rurality intersects with other identities, power dynamics, and structural inequalities—including those related to gender, race, disability, and age—to create unique patterns of human rights deprivations, violations, and challenges in rural spaces. Therefore, accurately assessing human rights and duties in rural spaces requires attention to the dynamics of rurality in a particular context, the unique nature of diverse rural identities and livelihoods, the systemic forces operating in and on those spaces, and the intersections with other forms of structural discrimination and inequality.[42]

The context of education refers to studies done to address discrimination in health care settings through educational interventions. As an example, Durán Kairies et al. describe how cardiovascular disease disproportionately affects Indigenous Peoples in Ontario.[43] Their research team was interested in determining the effect of a land-based educational intervention for professionals at a cardiac care center and university in a large urban city. The focus of their work was therefore categorized as direct. Durán Kairies et al. write that among the results they found was that participants, “by identifying and reflecting on their own power, positionality and privilege throughout the course, learned how to apply the knowledge they learned to create or further social change in the interest of equity and justice for Indigenous Peoples.”[44]

Gray literature and reports

Five reports from the Canadian Medical Association, Ontario Human Rights Commission, and others highlighted commitments to address discrimination. The Canadian Medical Association apologized for failing Indigenous health equity, outlining three commitments: advancing Indigenous health, supporting reconciliation, and promoting internal change. The Ontario Human Rights Commission announced a policy to tackle Indigenous-specific discrimination, with Chief Commissioner Patricia DeGuire calling it “intolerable.”[45]

In 2024, the Canadian Medical Association apologized to Indigenous Peoples for failing to adequately use its privileged position as one of the leading national voices of health care physicians to advance equitable access to health care for Indigenous Peoples.[46] As part of its statement, the association, in collaboration with its Indigenous partners, outlined three major national commitments moving forward: (1) advance Indigenous health; (2) support physicians’ journey to truth and reconciliation; and (3) promote reconciliation for association employees and leadership. In 2023, the association published an article on equity and diversity in medicine, highlighting how gender discrimination affects women and impacts patient care, along with how health care leaders can promote change through policy reform.[47]

In April 2024, the Ontario Human Rights Commission announced that it is working on a policy to address discrimination against Indigenous Peoples in the health care system. In the statement, Chief Commissioner Patricia DeGuire said, “Indigenous-specific discrimination is pervasive throughout our health care system. This is intolerable. The Commission calls for immediate and practical change. The engagements and the survey are the start of the Commission’s work to develop vital human rights guidance to help prevent and address this discrimination.”[48]

In 2023, Sophie Nicholls Jones wrote an article for the Ontario Medical Association noting that while progress has been made, much work needs to be done to address systemic racism in Canada. In that article, Mojola Omole, a board member of the Black Physicians’ Association of Ontario, in reflecting on her experience in medical school, said, “‘We didn’t really talk openly about systemic racism. We didn’t talk about what microaggressions are.’”[49] To remedy this experience, the article suggests increasing black representation in medical schools and reviewing the curriculum to examine implicit and explicit bias and how faculty and the student body contribute to its perpetuation.

Discussion

Tribunal review: Strengths, limitations, options for mediation, and intersecting grounds

This review analyzes human rights tribunal cases, unlike many scoping reviews. Western democracies designate tribunals and courts to adjudicate human rights claims, particularly in health care discrimination. HRTO cases often result in remedies such as compensation and policy revisions, but, as noted in many of the cases reviewed, face jurisdictional limits, particularly concerning clinical decisions, because they require arbitrariness to be deemed discriminatory. HRTO adjudicators, while experts in human rights law, are not medical experts and frequently defer to clinicians when assessing the appropriateness of clinical interventions for a given patient, unless there is clear prima facie evidence that a decision was arbitrary. With its procedural and legal burden of proof, the formal tribunal process is not well-positioned to address the unconscious bias prevalent in many health care settings.

Jasmine Marcelin et al. discuss how unconscious bias affects patient-clinician interactions within health care settings.[50] Dipesh Gopal et al. highlight that bias can influence clinical decision-making, contributing to diagnostic errors and cognitive biases that impact patient safety.[51] Although the formal tribunal process is not well suited to finding unconscious bias as part of its adjudication decisions, tribunals can still encourage alternative forms of resolution and disposition. Mediation is an effective means to address these experiences because it is a different kind of procedure than the adversarial method characterizing the formal tribunal process.[52]

Mediation resolves nearly 60% of HRTO cases before they reach the formal adjudication stage.[53] The HRTO promotes mediation, announcing in October 2024 that it is “preparing to launch a mandatory mediation process whereby all applications will proceed to a mediation, after confirming jurisdiction. Mediations have proven to be very successful in resolving applications at the HRTO and are aligned with the HRTO’s mandate, which encourages resolution through alternative dispute resolution methods rather than traditional adversarial approaches.”[54] Given these directions, health care providers might consider investing in mediation training and processes to resolve discrimination claims early to arrive at faster remedies and drive policy changes.

Another issue identified in the review of HRTO cases was that applicants frequently selected multiple grounds of discrimination regarding their personal characteristics. In the HRTO cases reviewed, many applicants claimed multiple grounds of discrimination in a single case, and most often, the adjudicator analyzed each ground separately, as this is a standard adjudication procedural process. However, as noted by the Ontario Human Rights Commission, the Supreme Court of Canada has recognized the problem with this approach:

Writing for the minority in the Mossop case, Madam Justice L’Heureux-Dubé remarked, “it is increasingly recognized that categories of discrimination may overlap, and that individuals may suffer historical exclusion on the basis of both race and gender, age and physical handicap or some other combination … categorizing such discrimination as primarily racially oriented, or primarily gender-oriented, misconceives the reality of discrimination as it is experienced by individuals. Discrimination may be experienced on many grounds, and where this is the case, it is not meaningful to assert that it is one or the other. It may be more realistic to recognize that both forms of discrimination may be present and intersect.”[55]

Most applicants, as found in the analysis of the HRTO cases, claimed multiple grounds. This review suggests that the experience of intersecting grounds of discrimination and the impact of such intersections should be an essential focus for the judiciary and health and social scientists. The reality of intersecting identities when assessing and interpreting discrimination is an important area for further research because, as noted by Justice L’Heureux-Dubé, it reflects lived experience. Models and interventions addressing people presenting with intersecting grounds is a promising area of further inquiry and development.

COVID-19 and discrimination claims

COVID-19 public health interventions raised significant public controversy and became highly politicized during this scoping review’s time frame. Consequently, it is important in the interest of a more fulsome review to briefly discuss some of the literature surrounding the pandemic in relation to discrimination in health care. Vaccine hesitancy was stronger among minority and lower socioeconomic groups in Canada.[56] Groups such as the Canadian Civil Liberties Association called attention to the human rights concerns and civil liberty implications of COVID-19 public health interventions.[57] Kevin Bardosh notes that too many human rights organizations were silent during this period, a moralizing narrative tended to accompany interventions, and there was very little tolerance for debate or dissent, hallmarks of liberal democracies.[58] Irrespective of where one lands on the public health policy response to COVID-19, there is broad consensus among leading Canadian physicians, health organizations, and advocates that a national inquiry into Canada’s COVID-19 response is required to address a range of issues related to the impact of the public health interventions, including differential impacts for minority groups and important civil liberties implications.[59]

Rurality as a protected area

Lyons’s identification of rurality and the systemic forces operating in rural spaces, combined with the intersections with other forms of structural discrimination and inequality, is a unique perspective and deserves further and more sustained analysis in Ontario. Statistics Canada provides the foundational framework for rural definitions in health data.[60] Many of Ontario’s health organizations adopt these definitions.[61] The health care gap in Ontario between urban and rural/small population centers is marked by disparities in provider access, service availability, travel burdens, wait times, health outcomes, infrastructure, and workforce retention.

Rural and small population centers face systemic challenges, including fragmented mental health services and reliance on urban centers for specialized care. Injury rates, particularly from motor vehicle collisions, increase with rurality due to longer driving distances and hazardous work environments (e.g., agriculture).[62] Rural physicians are forming associations and groups to address the unique needs of people in rural settings. Ruth Wilson et al., for example, note that

policy decisions are often guided by urban health care models without understanding the potential negative effects in rural communities. Rural communities need rural-based solutions and to develop regional capacity to innovate, experiment, and discover what works. An opportunity exists to narrow health disparities by providing care closer to home. Rural communities need an effective health care system with a stable workforce.[63]

The literature, including Wilson et al., identifies several strategies aimed at developing evidence-based rural health care planning that accounts for unique community needs.[64] The Canadian Medical Association recommends strengthening workforce retention through the implementation of immigration policies to attract health care workers to rural areas, paired with supports such as competitive salaries and community integration.[65] The Canadian Mental Health Association calls for improved funding models to account for rural disparities, adequate resources for mental health and specialized care, and better data to optimize resource distribution.[66]

Conclusion

The purpose of this scoping review was to discover common themes regarding instances of direct or systemic health care discrimination in Ontario; find out what is currently being done to prevent discrimination; and summarize the literature’s recommendations for how the health care system can build a more inclusive and responsive approach to the needs of diverse groups. Implicit in this scoping review was the presumption that most Canadians view health care as a fundamental entitlement. As noted by the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology:

the existence of public opinion polls that reveal that Canadians, encouraged by politicians and the media, believe they have a constitutional right to receive health care even though no such right is explicitly contained in the Charter. Nor does any other Canadian law specifically confer that right, although government programs exist to provide publicly funded health services.[67]

Scoping reviews like this one provide people invested in this issue the necessary data to move forward with meaningful reforms that preserve the value of Canada’s publicly funded and accessible health care system, which is rightly a source of pride for Canadians.[68]

The next steps for those invested in building a functional, inclusive public health care system in Ontario are to build on the findings of this review to address the discrimination currently present in the province’s health care system and to support meaningful and measurable remedies, including advancing proposals to enshrine the right to health as a positive, constitutional right. A rights-based approach to health care can provide leverage for groups to advocate for equitable resources to support the realization of a right to health and offer remedies for those who lack timely access to health care and who face marginalization from the health care system. Much is being done already, and these promising directions require ongoing support, sustained attention, and commitment from all stakeholders and citizens of the province. Other jurisdictions, similarly, ought to review their contexts and share those findings in public venues such as journals, conferences, and other settings so that all of us invested in health and human rights can co-construct improved systems that approximate more closely the aspirations of numerous human rights instruments that support and drive these efforts.

George Drazenovich is a PhD candidate, Lakehead University, Canada.

Please address correspondence to George Drazenovich. Email: gadrazen@lakeheadu.ca.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2025 Drazenovich. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

[1] Nishnawbe Aski Nation, “Inquest into Tragic Death of Ruthann Quequish Shows Neglect, Racism, and Chronic Underfunding” (August 16, 2024), https://www.nan.ca/news/inquest-into-tragic-death-of-ruthann-quequish-shows-neglect-racism-chronic-underfunding.

[2] S. Law, “Inquest into Ruthann Quequish’s Death Begins in Thunder Bay,” CBC News (July 26, 2024), https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/ruthann-quequish-inquest-1.7274890.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ontario Ministry of the Solicitor General, “Coroner’s Inquests’ Verdicts and Recommendations,” Government of Ontario (2024), https://www.ontario.ca/page/coroners-inquests.

[5] Nishnawbe Aski Nation (see note 1).

[6] Andrews v. Law Society of British Columbia [1989] 1 S.C.R. 143; Ontario Human Rights Commission v. Simpsons-Sears Ltd. [1985] 2 S.C.R. 536; British Columbia (Public Service Employee Relations Commission) v. BCGSEU [1999] 3 S.C.R. 3; Quebec (Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse) v. Bombardier Inc. [2015] 2 S.C.R. 789.

[7] Ontario Human Rights Commission, “Forms of Discrimination,” in Policy on Ableism and Discrimination Based on Disability (2024), https://www3.ohrc.on.ca/en/policy-ableism-and-discrimination-based-disability/6-forms-discrimination.

[8] A. R. Chapman, Global Health, Human Rights, and the Challenge of Neoliberal Policies (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

[9] L. O. Gostin and E. A. Friedman, “Towards a Framework Convention on Global Health: A Transformative Agenda for Global Health Justice,” Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law, and Ethics 13/1 (2013).

[10] Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11; C. M. Flood and B. Thomas, “Health Care as a Human Right: The Canadian Experience,” in European Parliament (ed), The Right to Health: A Comparative Law Perspective (European Parliament Think Tank, 2022).

[11] Chaoulli v. Quebec (Attorney General) [2005] 1 S.C.R. 791, para. 123.

[12] B. Porter, “Twenty Years of Equality Rights: Reclaiming Expectations,” Canadian Bar Review 83/2 (2004).

[13] V. Abban, Getting It Right: What Does the Right to Health Mean for Canadians? (Wellesley Institute, 2015).

[14] S. Hamed, H. Bradby, B. M. Ahlberg, and S. Thapar-Björkert, “Racism in Healthcare: A Scoping Review,” BMC Public Health 22/1 (2022); S. Merz, T. Aksakal, A. Hibtay et al., “Racism Against Healthcare Users in Inpatient Care: A Scoping Review,” International Journal for Equity in Health 23/89 (2024).

[15] Canadian Medical Association, “Public and Private Health Care: Surveys on Public and Private Health Care in Canada,” https://www.cma.ca/our-focus/public-and-private-health-care/what-we-heard-surveys.

[16] B. Allan and J. Smylie, First Peoples, Second Class Treatment: The Role of Racism in the Health and Well-Being of Indigenous Peoples in Canada (Wellesley Institute, 2015); E. McGibbon and C. McGibbon-Wynter, “Anti-Black Racism and Health: Quantifying the Impact in Canada,” Canadian Journal of Public Health 114/3 (2023); S. Nestel, Colour Coded Health Care: The Impact of Race and Racism on Canadians’ Health (Wellesley Institute, 2012).

[17] J. M. Cénat, “Racial Discrimination in Healthcare Services Among Black Individuals in Canada as a Major Threat for Public Health: Its Association with COVID-19 Vaccine Mistrust and Uptake, Conspiracy Beliefs, Depression, Anxiety, Stress, and Community Resilience,” Public Health 230 (2024).

[18] W. Phillips-Beck, R. Eni, J. G. Lavoie, et al., “Confronting Racism Within the Canadian Healthcare System: Systemic Exclusion of First Nations from Quality and Consistent Care,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17/22 (2020).

[19] D. Martin, A. P. Miller, A. Quesnel-Vallée, et al., “Canada’s Universal Health-Care System: Achieving Its Potential,” Lancet 391/10131 (2022), p. 1718.

[20] Canada Health Act, RSC 1985, c C-6.

[21] Human Rights Code, RSO 1990, c H.19.

[22] L. Cornejo Chavez, “New Remedial Responses in the Practice of Regional Human Rights Courts: Purposes beyond Compensation,” International Journal of Constitutional Law 15/2 (2017); G. L. Neuman, “Bi-Level Remedies for Human Rights Violations,” Harvard Human Rights Journal 27 (2014).

[23] A. C. Tricco, E. Lillie, W. Zarin, et al., “PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation,” Annals of Internal Medicine 169/7 (2018).

[24] Hamed et al. (see note 14); Merz et al. (see note 14).

[25] Canadian Legal Information Institute, “What Is CanLII,” https://www.canlii.org/en/info/about.html.

[26] A.H. v. Ontario (Children, Community and Social Services) [2021] HRTO (CanLII).

[27] Beckford v. Ontario (Solicitor General) [2022] HRTO (CanLII).

[28] Pankoff Estate v. The Corporation of the City of St. Thomas [2022] HRTO (CanLII).

[29] Fife v. Sienna Senior Living Inc. [2024] HRTO 544 (CanLII).

[30] Ibid.

[31] Powell v. Ontario (Solicitor General) [2023] HRTO 345 (CanLII), para. 119.

[32] Ibid., para. 119.

[33] Parratt v. Lakeridge Health [2021] HRTO (CanLII).

[34] Moshi v. Ontario (Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services) [2014] HRTO 1044 (CanLII), para. 43.

[35] Oulds v. Bluewater Health [2023] HRTO 1134 (CanLII), para. 9.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid., paras. 12–13.

[38] Ibid., paras. 17–20.

[39] A. P. Belon, J. L. Chew, N. Schwartz, et al., “Variability in Public Health Programming and Priorities to Address Health Inequities Across Public Health Units in Ontario, Canada,” Canadian Journal of Public Health 115/5 (2024).

[40] Javiera-Violeta Durán Kairies, E. J. Rice, S. Stutz, et al., “Transform[ing] Heart Failure Professionals with Indigenous Land-Based Cultural Safety in Ontario, Canada,” PLOS One 19/5 (2024).

[41] Belon et al. (see note 39).

[42] A. Lyons, “Rurality as an Intersecting Axis of Inequality in the Work of the U.N. Treaty Bodies,” Washington and Lee Law Review 79/3 (2022), p. 1125.

[43] Durán Kairies et al. (see note 40).

[44] Ibid., p. 10.

[45] Ontario Human Rights Commission, “OHRC Announces Development of Policy to Address Indigenous-Specific Discrimination in Ontario’s Healthcare System,” https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/ohrc-announces-development-policy-address-indigenous-specific-discrimination-ontarios-healthcare.

[46] Canadian Medical Association, The CMA’s Apology to Indigenous Peoples (2024).

[47] Canadian Medical Association, “Equity and Diversity in Medicine: Addressing Gender Discrimination,” CMAJ 195/10 (2023).

[48] Ontario Human Rights Commission, “OHRC Announces Development” (see note 45).

[49] S. N. Jones, “Increasing Black Representation at Ontario’s Medical Schools Will Lead to More Black Doctors, Say Physicians,” Ontario Medical Association (February 23, 2023), https://www.oma.org/news/2023/february/increasing-black-representation-at-ontarios-medical-schools-will-lead-to-more-black-doctors-say-physicians/.

[50] J. R. Marcelin, D. S. Siraj, R. Victor, et al., “The Impact of Unconscious Bias in Healthcare: How to Recognize and Mitigate It,” Journal of Infectious Diseases 220/Suppl 2 (2019).

[51] D. P. Gopal, U. Chetty, P. O’Donnell, et al., “Implicit Bias in Healthcare: Clinical Practice, Research and Decision Making,” Future Healthcare Journal 8/1 (2021).

[52] Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, “Mediation,” https://www.chrt-tcdp.gc.ca/en/human-rights/process/mediation.

[53] Millard and Company, “Why Do Most Human Rights Claims Settle?” (March 10, 2020), https://www.millardco.ca/2020/03/why-do-most-human-rights-claims-settle.

[54] Tribunals Ontario, “HRTO Operational Update: Updates to HRTO Rules of Procedure” (October 25, 2024), https://tribunalsontario.ca/2024/10/25/hrto-operational-update-updates-to-hrto-rules-of-procedure.

[55] Ontario Human Rights Commission, “An Intersectional Approach to Discrimination: Addressing Multiple Grounds in Human Rights Claims,” Discussion Paper (2001), https://www.ohrc.on.ca/sites/default/files/attachments/An_intersectional_approach_to_discrimination%3A_Addressing_multiple_grounds_in_human_rights_claims.pdf.

[56] J. M. Cénat, P.-G. Noorishad, S. M. Mahdi Moshirian Farahi, et al., “Prevalence and Factors Related to COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Unwillingness in Canada: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Medical Virology 95/1 (2023).

[57] Canadian Civil Liberties Association, Canadian Rights During COVID-19: Interim Report on COVID-19’s Second Wave (2021).

[58] K. Bardosh, “COVID Vaccine Mandates in Canada Were a Mistake: Are We Ready to Learn the Right Lessons?,” Macdonald-Laurier Institute (November 24, 2022), https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/covid-vaccine-mandates-in-canada-were-a-mistake-are-we-ready-to-learn-the-right-lessons/.

[59] Ibid.; Royal Society of Canada, “Lessons from Canada’s Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Path Forward: Launch of a Series in The BMJ” (July 25, 2023), https://rsc-src.ca/en/events/covid-19/lessons-from-canadas-response-to-covid-19-pandemic-and-path-forward-launch-series; S. Kirkey, “Canada Needs a National COVID-19 Inquiry Now,” National Post (July 24, 2023), https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/canada-covid19-inquiry; L. Pelley, “Top Medical Experts Call for National Inquiry into Canada’s COVID-19 ‘Failures,’” CBC News (July 24, 2023), https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/top-medical-experts-call-for-national-inquiry-into-canada-s-covid-19-failures-1.6916419.

[60] Statistics Canada, “Census Dictionary” (August 17, 2021), https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/ref/dict/index-eng.cfm.

[61] Canadian Mental Health Association, “Rural and Northern Community Issues in Mental Health,” https://ontario.cmha.ca/documents/rural-and-northern-community-issues-in-mental-health.

[62] F. Bang, S. McFaull, J. Cheesman, and M. T. Do, “The Rural-Urban Gap: Differences in Injury Characteristics,” Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice 39/12 (2019).

[63] C. R. Wilson, J. Rourke, I. F. Oandasan, and C. Bosco, on behalf of the Rural Road Map Implementation Committee, “Progress Made on Access to Rural Health Care in Canada,” Canadian Family Physician 66/1 (2020), p. 31.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Canadian Medical Association, “Does Where I Live Affect My Health Care?,” https://www.cma.ca/healthcare-for-real/does-where-i-live-affect-my-health-care.

[66] Canadian Mental Health Association, “Rural and Northern Community Issues” (see note 64).

[67] Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology, The Health of Canadians: The Federal Role, Volume Six: Recommendations for Reform (Senate of Canada, 2002), p. 101.

[68] Canadian Press, “Poll: Canadians Are Most Proud of Universal Medicare,” CTV News (November 25, 2012), http://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/poll-canadians-are-most-proud-of-universal-medicare-1.1052929; Canadian Medical Association, “Public and Private Health Care” (see note 15).