Volume 22/2, December 2020, pp 271 – 384

Agustina Ramón Michel, Stephanie Kung, Alyse López-Salm, and Sonia Ariza Navarrete

Abstract

Claims of conscientious objection (CO) have expanded in the health care field, particularly in relation to abortion services. In practice, CO is being used in ways beyond those originally imagined by liberalism, creating a number of barriers to abortion access. In Argentina, current CO regulation is lacking and insufficient. This issue was especially evident in the country’s 2018 legislative debate on abortion law reform, during which CO took center stage. This paper presents a mixed-method study conducted in Argentina on the uses of CO in health facilities providing legal abortion services, with the goal of proposing specific regulatory language to address CO based not only on legal standards but also on empirical findings regarding CO in everyday reproductive health services. The research includes a review of literature and comparative law, a survey answered by 269 health professionals, and 11 in-depth interviews with stakeholders. The results from our survey and interviews indicate that Argentine health professionals who use CO to deny abortion are motivated by a combination of political, social, and personal factors, including a fear of stigmatization and potential legal issues. Furthermore, we find that the preeminent consequences of CO are delays in abortion services and conflicts within the health care team. The findings of this research allowed us to propose specific regulatory recommendations on CO, including limits and obligations, and suggestions for government and health system leaders.

Introduction

In practice, the way in which conscientious objection (CO) is currently used is quite different from the use originally proposed by liberalism. CO was meant to protect citizens’ autonomy and moral pluralism in society.1 However, CO in health care has been expanding since 1970, particularly regarding euthanasia and abortion.2 This broad use of CO has created and worsened barriers to accessing certain health services.3

The majority of countries in the Global North allow health care providers to invoke CO through “refusal” or “conscience” clauses. In some countries, policies allow for entire health care institutions to refuse to provide specific services (institutional CO).4 In the European Union, 21 countries formally recognize CO;5 in other parts of the world, including Latin America, policies regarding CO are less clear. Governments in Colombia, Uruguay, and Chile have passed specific regulations on CO, often alongside the liberalization of abortion laws.5

In Argentina, since the adoption of national laws on sexual and reproductive rights in 2002, CO has been explicitly included as a right belonging to health professionals. Ten years later, the Argentine Supreme Court ratified CO as a right in cases of legal abortion.6 During the 2018 debate to expand abortion rights, the discussion around CO was particularly contentious.

In this paper, we focus on an important legal and policy gap to be filled in the region—the need to better define and regulate CO to abortion—based on a more in-depth understanding of CO and its current uses, which we consider to be one of our main contributions to the literature on this subject.7 Argentina has no regulation that adequately addresses the use, abuse, and misuse of CO in the context of abortion services. Argentina is currently undergoing changes to further liberalize abortion laws. The 2018 debate on the liberalization of abortion rights was preceded by a significant national movement advocating for improved access to abortion services under the current law. Our exploration of the uses of CO among providers in Argentina led to our proposed regulatory language to ensure women’s rights related to abortion access. Although this study took place in Argentina, we believe it to be useful for advocates, legal professionals, and policymakers in other settings.

Methods

This study occurred in three phases. First, we reviewed jurisprudence and literature to understand the ways in which CO has and has not been addressed by Argentine law and global scholars. Questions that arose were discussed and clarified with experts in the fields of human rights law and medicine. This review informed the development of our survey and in-depth interview guides.

For the second phase, we developed a cross-sectional survey disseminated to a non-representative sample of sexual and reproductive health providers in Argentina’s public health care system. The survey included 20 questions, 6 of which were open ended. Respondents were asked for demographic data and responded to questions about their participation in sexual and reproductive health and abortion services; definitions and understandings of CO; and the impact of CO on women and health services.

In the third phase, we conducted semi-structured interviews (n=11) between April and July 2018 with provincial managers of sexual and reproductive health programs and heads of health departments identified by the research team, none of whom self-identified as objectors. This was done with the aim of enriching survey data. Possible participants were identified using membership lists from pro-choice organizations in Argentina. Those who agreed to participate were also asked to identify others who might be willing to take the survey. We developed semi-structured interview guides focused on participants’ professional experience and current job responsibilities, their religious identity and practices, opinions on CO, causes or motivations for CO among health care professionals, and perceived consequences of CO for patients and health care teams. Interviews were carried out via Skype or in person and lasted for an average of 45 minutes. All interviews were conducted, recorded, and transcribed in Spanish. Interviews were stored on password-protected devices, and IDs were created to protect anonymity. The first and last authors analyzed transcriptions using thematic analysis and developed a codebook using a priori themes. Other members of the research team reviewed the codebook; edits and clarifications were made as needed. This study received ethical approval from the institutional review board at the Hospital Británico in Buenos Aires.

Results

Survey participant characteristics

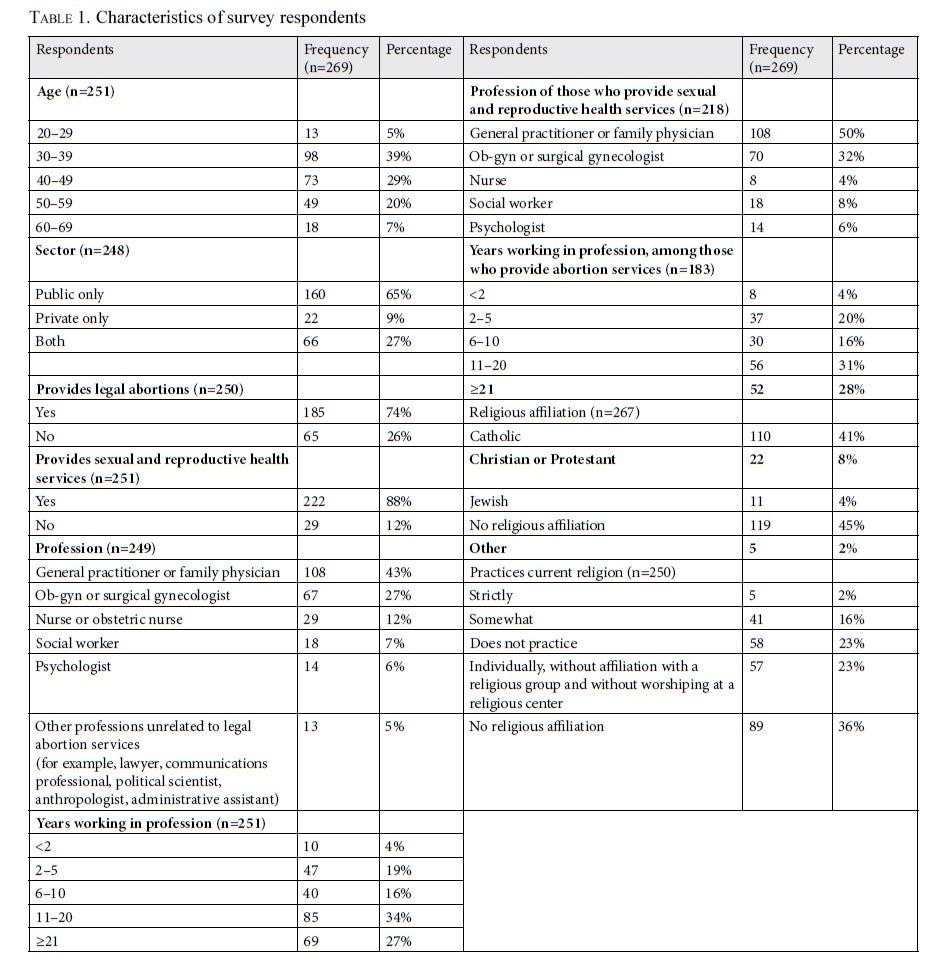

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of survey respondents. The age group with the highest proportion of respondents was 30–39 years old (39%). A large majority (92%) of respondents work in the public sector, and most (88%) provide sexual and reproductive health services. Of those who provide those services, 72% are physicians (general practitioners, ob-gyns, or surgical gynecologists). More than half of respondents who provide abortion services (59%) have been practicing medicine for over 10 years, with 28% having more than 20 years of experience. Nearly half of respondents (45%) have no religious affiliation, and among those that do, 41% currently practice their religion.

The Argentine legal context

Argentine legislation explicitly allows for CO in several reproductive health services.8

Regarding abortion, the Guía nacional para la atención integral de personas con derecho a la interrupción legal del embarazo (National Guide on Comprehensive Care for People with the Right to the Termination of Pregnancy) also allows individual health professionals to claim CO with some limitations. Further, the Supreme Court has authorized providers, including those working in the public sector, to request exemption from providing abortion on moral or religious grounds.9 Most of Argentina’s 23 provinces have adopted similar guidelines. Currently, all provincial policies on abortion acknowledge CO, without clarifying its procedures or conditions, except for the provinces of Santa Fe, Mendoza, and San Luis, all of which have more specific legislation.10

In June 2018, the lower house of the Argentine National Congress passed a bill expanding abortion rights. The bill also granted individual CO and explicitly banned institutional CO. The Senate rejected this bill in August of the same year.

Conscientious objection in practice: Unexpected applications

Our analysis revealed that surveyed respondents believe that CO to abortion has been used by some health professionals to pursue political goals associated with traditional views on sexuality, gender roles, and family structures. Among all survey respondents, 47% believe that CO is used to resist policies favorable to sexual and reproductive rights.

This belief was supported by qualitative findings. Respondents expressed that hospital authorities (such as directors, chiefs of service, and faculty) have used CO to establish an ideological approach to sexual and reproductive health care in their departments. One of the sexual and reproductive health coordinators interviewed stated, “In hospitals, you find people saying ‘The CO [form] must be signed,’ and those orders came from department heads.” According to our literature review, CO is not so much a mechanism to which marginalized minorities resort but is instead leveraged by majorities and privileged sectors of society to resist social and legal changes. This appears to be especially true regarding abortion services, enabling these professionals to impose what they consider to be “right,” preventing patients from exercising their rights.11

Our research also points to other, less obvious uses of CO. We call these “defensive uses of CO,” which occur when health professionals who, under especially challenging conditions for abortion provision, resort to CO. These professionals are often not driven by moral reasons, but instead wish to avoid inconveniences or criticism related to abortion stigma. For example, 60% of survey respondents believe that objection to abortion occurs out of fear of stigmatization. In the words of a one service provider:

In general, they argue that performing an abortion puts them in a stressful and uncomfortable situation, which exceeds their ability to perform the abortion. They do not want to be identified as abortionists.

In the survey and interviews, CO was also identified as being used as a protective mechanism. This often stemmed from misunderstanding or ignorance of the law or fear of potential problems that health professionals thought they would face after providing abortion services. In other cases, professionals simply use CO to avoid heavy workloads due to the small number of health professionals available to provide abortions: 54% of survey respondents believe that CO is used to avoid more work. As one health care administrator stated:

I remember one physician that said to me, “I signed it because we had the feeling people would come in droves to have abortions, and we would have to deal with all that.”

Conditions surrounding CO and its consequences

The majority of survey respondents (82%) identified delays in care or barriers in access to abortion procedures as the main effect of CO, followed by the stigmatization of reproductive health services (68%). According to the survey, in many cases, CO was seen as an excuse to abuse medical authority and even to mistreat patients.

Among our sample, others expressed that a lack of clear regulations on CO can affect freedom of conscience among abortion providers. These providers often work in environments where CO is the “norm.”12 Although these professionals fulfill their obligations, they face stigma, marginalization, and harassment. Hence, they pay a very high price to exercise their freedom of conscience, as opposed to the professionals who refuse to provide abortion services. As one of the respondents shared:

One of the physicians who is a legal abortion provider has had many problems, and the others, who are hypocrites, make it difficult for him to work. They have denied him entrance to a clinic here. Even the head of the department admits [this situation].

As a result, many of these abortion providers—especially those who are isolated from a network of other safe abortion providers—do not speak openly about their work.13 One of the respondents stated:

I don’t like receiving patients from other hospitals. I don’t like our facility to be seen as a facility that receives cases that others are not willing to treat.

This paradox of asymmetric legitimacy creates an imbalance between professionals who deny abortion services and those who provide them. This imbalance is driven by the decisions or omissions of department heads. One in three people surveyed (33% of respondents) consider that health care authorities influence the use of CO among younger professionals, and 30% of respondents believe that the lack of leadership and clear guidance increases the use of CO. In some cases, leadership directly affects health professionals’ decision to use CO—38% of respondents believe that some colleagues resort to CO following mandates from their bosses. According to one respondent:

I believe the department head is not the same as a physician. I dare say that a requirement to be head of a department, for example of obstetrics and gynecology, should be not being a conscientious objector. I believe this cadre needs to safeguard certain issues, especially those related to medicine, which is such a hierarchical profession.

Many respondents believe that unclear regulations surrounding CO leads to an unfair distribution of tasks within health care teams. In this regard, 58% of survey respondents believe that CO creates a work overload for abortion providers, and 72% stated that this leads to tension within teams. As one respondent shared:

In general, from what I’ve seen, few cases are actual objections. They are false objections, either because providers don’t know what CO really means, or because they do not want to be involved in a sensitive issue, since it is easier not to become involved. Of course, this results in work overload for those who do provide the service. The fatigue this causes often makes them want to become objectors as well … due to the fatigue and stigma from their colleagues who are false objectors.

In fact, there is a status quo of impunity regarding the breach of professional duties, which supports the abuse of CO.14 As one respondent stated:

At this facility, there is a pharmacist who refuses to order contraceptives bi-monthly and distribute them … Regarding legal termination of pregnancy, the same person tried to hinder that practice and convince providers that it is wrong. All these attitudes are supported by the director of the facility, as she does not want to “create conflict.”

Legal acceptability

Although judicial cases in Argentina acknowledge CO as a legitimate concept, positions on its legal acceptability and limits differ. Some respondents believe that CO in health care is unacceptable, primarily because it negatively affects those who need health services and health care teams. As one survey respondent stated, “Objectors are, in fact, abandoning their patients.” Along similar lines, most respondents (70%) believe that the use of CO leads to a breach of professional duties.

In addition, some believe that the right to health and other rights have a veto effect on the acceptability of CO to abortion.15 As one respondent stated, “If a person chooses to practice medicine, they can never put their beliefs before patients’ rights.” Similarly, a slight majority of respondents (52%) believe that CO should not be allowed in health care contexts.

Likewise, many respondents believe that CO to sexual and reproductive health services is particularly discriminatory.16 Those with lower social or economic capital are especially unlikely to have resources to overcome barriers imposed by CO. Most respondents (74%) believe that CO is based on biases against women, and a majority (59%) believe that it is based on discrimination against some women in particular.

On the other hand, few respondents (7%) believe that CO is a fundamental right; therefore, its restriction must be exceptional and established by law. In general, these respondents relate CO with religious beliefs.

There are also those who hold more nuanced views, positioning CO as a conflict between individuals’ values and rights, for which they promote ways to resolve this conflict.17 They argue that the government must ensure both freedom of conscience and the right to health. In this regard, CO in health care contexts must always be limited by the institutions and individuals charged with ensuring access to health care. Forty-eight percent of providers surveyed believe that CO should be permitted. As one provider stated, “I’m okay with objectors as long as they are honest enough to always refer patients to someone who provides this service.”

Others see CO as a mechanism for managing some health professionals’ resistance to abortion in a way that still allows for access to this care. This was the vision of those who designed the pioneering CO policy in the province of Santa Fe in 2010.18 This position assumes that CO must be reviewed thoroughly in legal and public policy regulations. In this regard, some respondents expressed viewpoints like that of the following health professional:

Conscientious objection must be de-ideologized, and it should be taken seriously with all it entails as a barrier and comfort zone, and with all that it implies as a challenge for health policy to ensure coordination, control, governance, standardization, legitimization—in sum, everything a health policy should do.

Discussion

Liberalism justifies CO as a way of protecting the moral integrity of minority groups within a given society.19 However, this study shows that health professionals in Argentina have sought to extend the use of CO far beyond its standard definition. In practice, some health professionals weaponize CO as a way to deteriorate access to safe, legal abortion services.

In particular, our study highlights conservative political uses of CO in Argentina. This echoes previous work that shows that CO is used for reasons other than moral, religious, and ethical reasons. Our study indicates that CO has been used as a “Trojan horse” to derail Argentina’s progress on sexual and reproductive rights, a pattern that threatens the lives and safety of pregnant people.

The consequences of using CO to deny abortion services fall first on providers guided by their conscience, but they fall hardest on pregnant people requiring abortion services.20 One of the most frequent and harmful consequences is the failure to hold objecting professionals accountable for ensuring patients’ access to care. On the contrary, in many regions of Argentina, abortion providers are informally punished, while formal accountability mechanisms for those who hamper abortion services and abuse their power are scarce and weak in nature.21 Such is the case with one provider mentioned previously, who was unable to secure employment at private clinics after being labeled an “abortionist.” Often, conscience and moral reasons seem to be attached only to those denying services, obscuring the conscience and morality of abortion providers and rendering these providers as morally inferior.

As described by the authors of a 2015 study, abortion providers report that their work is referred to as “dirty work” and as having “little scientific value.”22 Recent studies show that these connotations create significant stress and anxiety among abortion providers.23 Our analysis supports these studies, as denial of abortion services was partially explained by health professionals’ fear of stigmatization. Abortion providers interviewed refer to experiences of “loneliness,” “finger pointing,” “burnout,” and “work overload” when describing their work. Moreover, they fear that their job may lead to a lack of professional prestige or put them at risk for harassment.

Stigma and silence create a vicious cycle: when professionals do not disclose their role as abortion providers, or do not speak proudly about caring for those who need abortion services, their silence perpetuates stereotypes portraying abortion services as deviant care that “serious” physicians do not provide.24 This contributes to the marginalization of abortion providers and exposes them to further harassment, fatigue, and other injustices. Thus, this cycle continues via what Lisa Harris et al. call “the legitimacy paradox”: providers of these services are still seen by many as illegitimate, substandard doctors.25

Some sexual and reproductive health care providers in our sample believe that CO should not be permitted in health care facilities. Globally, only a few legal systems expressly prohibit the use of CO (Finland, Bulgaria, and Lithuania). This is based on the principle of legality and mandatory compliance with the law.26 Governments that prohibit CO justify their decision by acknowledging the special duties placed on health professionals and patients’ right to autonomy and nondiscriminatory services.

Comparative studies show that it is necessary to balance the decision that some providers make to refuse to provide abortion services on moral or religious grounds with the need to ensure access to abortion services and fairly distribute responsibilities within health care teams.27 As made evident in this study, CO in Argentina is often used in response to professional environments where abortion is highly stigmatized, often characterized by a limited number of abortion providers, weak or nonexistent government oversight, or strong opposition to reproductive rights.

A regulatory proposal

Unfortunately, many existing regulations related to CO have focused on what, how, and when a health care professional may refuse to provide abortion services, leaving the task of ensuring access solely to providers. As one of our survey respondents stated:

The best way to deal with CO is focusing on legitimacy, legality, and governance, dealing with the conditions [necessary] to ensure the practice, not focusing on the issue of objection. Legitimizing and creating mechanisms and strategies that facilitate governance. Going beyond training and awareness-raising, adjusting them to the 21st century, [and] including them in a more complex package.

Comments like these and our survey findings led us to propose specific regulatory language pertaining to the use of CO to deny abortion access. We also propose language that will guide the implementation of this clause, with specific guidelines for ensuring access to abortion while allowing providers to deny abortion on moral or religious grounds. Finally, we describe our rationale for each article of the proposed clause.

The proposal

The suggested regulation covers four key areas pertaining to health professionals’ refusal to provide abortion services on moral or religious grounds:

(1) the extent to which this refusal can be used by providers and corresponding duties:

(i) CO should be permitted only for individual providers (not for institutions)

(ii) CO must be based on moral or religious grounds, not on other motives such as ignorance of the law, workload issues, or fear of abortion stigma within institutions. Leadership needs to clearly differentiate and discourage other motivations to use CO and should be responsible for ensuring that objectors in their hospitals are not driven by other motivations through a review of their written refusal (see “How This Refusal Must Be Expressed” below).

(2) the limits associated with this refusal:

(i) providers cannot refuse to make a referral to a legal service or to give information on the right to an abortion

(ii) objectors should not be in leadership positions, as their status as objectors can negatively affect abortion access

(3) how this refusal must be expressed in order to be considered valid:

(i) CO must be expressed in writing to health facility authorities

(ii) the document used to record CO must include the moral or religious reasons and motives that underly the refusal to provide abortion services

(iii) the application must be reviewed and accepted by health authorities

(4) institutional responsibility to ensure access to abortion:

(i) national or provincial coordinating and administrative bodies are responsible for ensuring access to abortion within existing legal regulations, while also allowing providers to deny this care on moral or religious grounds

(ii) health care institutions and administrators are responsible and accountable for ensuring access to abortion services at all times

(iii) people who occupy leadership roles in health care settings should support access to abortion services in accordance with the law

Arguments for the regulatory proposal

The extent to which health professionals can refuse to provide abortion on moral or religious grounds and corresponding duties

The refusal should be based solely on moral or religious grounds, as this refusal is grounded in democratic constitutional rights of freedoms of expression and conscience. Leadership needs to clearly differentiate and discourage other motivations to use CO, such as workloads or lack of legal knowledge.

CO should be limited to individual health professionals who are directly involved in abortion care and should not be extended to ancillary personal or health institutions, as they do not have a conscience.

Information on abortion services in Argentina is deficient.28 This reality requires that all health professionals provide patients with the information necessary to access abortion. Accordingly, the proposed clause highlights the obligation to make good-faith referrals for abortion services so that refusals do not become a barrier to access.29 Lack of adequate referral systems can subject patients to a sort of pilgrimage, during which they travel to various facilities and professionals, requesting abortion and losing crucial time as their pregnancy progresses.

Partial refusal to provide abortion services is permitted. As stated, the regulation of abortion must take a pragmatic approach. By allowing for partial refusal, health systems may increase the number of available providers in facilities where resistance would otherwise severely limit access. It is necessary to clarify that this partial exception does not allow for discrimination toward patients based on individual characteristics, including age, nationality, ethnicity, gender identity, marital status, and situations surrounding a pregnancy. In Portugal, for instance, though groups opposed to a regulatory framework that allows for partial refusal consider this to be a positive regulatory outcome, many of those who support reproductive rights also view a nuanced gradation of objection as a positive development for abortion rights.30

Limits on the refusal to provide abortion services

The proposal includes two cases where the use of CO is prohibited. CO cannot be used by health care leaders, such as heads of health departments, health services coordinators, or chiefs of staff. According to our findings, health care leaders have a considerable influence on health care teams, both in terms of structuring services and organizational culture.31 In many cases, department heads have placed undue restrictions on the provision of abortion or have imposed illegal limitations on people with disabilities, adolescents, people with advanced pregnancies, and others. In other cases, the stance on abortion of those in leadership positions discourages health professionals under their authority from providing abortion.32 Therefore, leadership must commit to the provision of abortion services to ensure that professionals have no incentives to claim CO.

This restriction is reasonable for two reasons. First, the use of CO is available only to those providers who are tasked with directly providing abortion. Second, allowing health care leaders to formally refuse to provide abortion allows for the introduction of a moral position pertaining to these services and, potentially, at an institutional level.33

The exclusion of health care managers and administrators from the right to refuse abortion services does not constitute workplace discrimination. It is not based on suspect classifications, such as religious affiliation, as it does not exclude any particular religious group. The restriction is justified by recognition of the need for abortion service provision as mandated by law. The exclusion of these professionals takes place due to the facility’s needs and not as a result of individuals’ religious choice.

How this refusal must be expressed in order to be considered valid

The proposal establishes that the refusal must be expressed in writing to the highest authority within the health care facility. This formal expression must include motivations for said refusal. Acceptable explanations for permanently refusing to provide abortion are moral and religious in nature.

Our survey results show that CO is motivated primarily by reasons that are not moral or religious in nature, and may be identified and adequately addressed by ensuring that professionals submit, in writing, their motivations for refusal. The intention is not to question motivations or assess the religiosity or morality of any providers who submit objection on these grounds; rather, this policy makes clear to health professionals the legal reasons for the correct use of CO. Additionally, literature supports the submission of motivations for refusal in writing as important for promoting reflection among professionals who intend to formally refuse to provide abortions.34 This reflection is necessary to address the complexity of the assumed conflict between abortion and protecting a gestating fetus. The written refusal should be made when first starting to work at the facility, encouraging continued reflection.

Overall, regardless of whether providers’ moral or religious reasons are evaluated, it is necessary to distinguish other reasons for denying abortion services. As a result, the regulation explicitly mentions that reasons that stem from a lack of knowledge of scientific evidence or current legal standards, as well as those arising from discriminatory beliefs or practices, are unacceptable.

Formalizing the process for refusal provides two layers of assurance. On the one hand, it ensures that health care management has the necessary information to organize abortion provision. On the other, it allows refusing professionals to be exempted from the provision of abortion services. The proposal recommends allowing the exclusion of the refusal any time, as the professional becomes willing to provide abortion services.

Distribution of institutional responsibilities to ensure access to abortion services

The proposal establishes institutional responsibilities for each level of the health care system. Providers are the immediate guarantors of service access, local authorities are considered health facility administrators, and national health authorities serve a coordinating role. Together, these three levels are responsible for ensuring equal access to abortion nationwide.

The responsibilities and mechanisms described at each level are aimed at guaranteeing patients’ access to services. The proposal provides guidance on how to update policies pertaining to CO to ensure adequate availability of abortion. It also suggests ways for each level to implement supportive measures for abortion providers, acknowledging CO as an exception to a health system committed to providing abortion.

Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations. Findings from the qualitative component are not generalizable beyond Argentina or even within Argentina, given variation in abortion laws and access. However, our supplementation of qualitative findings with a quantitative survey helps increase our confidence in these results. Refusal by some professional networks invited to disseminate the survey resulted in the recruitment of respondents from pro-choice networks, likely oversampling abortion providers. This limitation also extends to our qualitative results, as respondents were similarly recruited. As a result, perspectives on CO shared here are largely those held by abortion providers and leaves a gap in our knowledge on the perspectives of people opposed to or undefined on their abortion-related values. Questions that focused specifically on the uses and consequences of CO broadly, and not explicitly each individual respondent’s use of CO, helped ensure that their observations were captured. We believe that the providers interviewed are integral parts of health care teams who are familiar with the opinions held by objecting professionals. Further research is needed to explore how health professionals—especially professionals who are objectors—may respond to CO regulations such as those we are suggesting. A health systems analysis is imperative to monitor how CO interventions affect abortion provision and access.

Conclusion

This article identifies various ways that CO is used in Argentina that fall outside the scope originally imagined by liberalism. These include fear of stigmatization, increased workload, lack of knowledge of the law, and fear of legal repercussions. CO was also reported to have various impacts on women and health care teams, including further stigmatization, delays in care, increased workload for providers, and conflict among health care teams. A lack of clear regulation contributes to the misuse of CO, including institutional CO and the use of CO by hospital leadership.

We believe that Argentina is in the midst of a historic moment for abortion access. The question is not if but when abortion laws will be expanded, due to both the immense social movement in favor of safe, legal abortion (known as “the green tide”) and the likelihood that legislation to expand abortion rights will be approved. We are optimistic regarding the usefulness of our proposal for informing the language and implementation of this legal reform.

Finally, we propose clear regulatory language that we believe is necessary to ensure access to abortion. This access is urgently needed to guarantee the right of every woman and pregnant person to health, self-determination, and access to modern medical technologies. We believe that this proposal can be adapted for use in diverse social and political contexts.

Agustina Ramón Michel, Esq. LLM, is an Associate Researcher at the Centro de Estudios de Estado y Sociedad and Professor of Law at Palermo University, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Stephanie Kung, MPH, is a Research, Monitoring, and Evaluation Advisor at Ipas, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Alyse López-Salm, MPH, CHES, is a Senior Development Strategist at Ipas, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Sonia Ariza Navarrete, Esq. LLM, is an External Researcher at the Centro de Estudios de Estado y Sociedad, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Please address correspondence to Sonia Ariza Navarrete. Email: soniaarizanavarrete@gmail.com.

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2020 Ramón Michel, Kung, López-Salm, and Ariza Navarrete. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction.

References

- M. Magelssen, N. Quang Le, and M. Supphellen, “Secularity, abortion, assisted dying and the future of conscientious objection: Modelling the relationship between attitudes,” BMC Medical Ethics 20/1 (2019), p. 65.

- S. Clark, “Two concepts of conscience and their implications for conscience-based refusal in healthcare,” Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 26/1 (2017), pp. 97–108; Guttmacher Institute, Refusing to provide health services (2019); W. Chavkin, L. Leitman, and K. Polin, “Conscientious objection and refusal to provide reproductive healthcare: A white paper examining prevalence, health consequences, and policy responses,” International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 123/Suppl 3 (2013), pp. S41–S56; L. Casas, “Invoking conscientious objection in reproductive health care: Evolving issues in Peru, Mexico and Chile,” Reproductive Health Matters 17/34 (2009), pp. 78–87.

- Chavkin et al. (2013, see note 2).

- C. Fiala, K. Gemzell Danielsson, O. Heikinheimo, et al., “Yes we can! Successful examples of disallowing ‘conscientious objection’ in reproductive health care,” European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care 21/ 3 (2016), pp. 201–206.

- Fiala et al. (see note 4); Chavkin et al. (2013, see note 2); L. Cabal, M. Arango Olaya, and V. Montoya Robledo, “Striking a balance: Conscientious objection and reproductive health care from the Colombian perspective,” Health and Human Rights Journal 16/2 (2014), pp. E73–E83; V. Undurraga and M. Sadler, “The misrepresentation of conscientious objection as a new strategy of resistance to abortion decriminalization,” Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 27/2 (2019), pp. 17–19.

- A. Ramón Michel, S. Ariza, and A. Allori, Regulaciones de la objeción de conciencia sanitaria en Argentina (unpublished work, 2020).

- W. Chavkin, L. Swerdlow, and J. Fifield, “Regulation of conscientious objection to abortion: An international comparative multiple-case study,” Health and Human Rights Journal 19/1 (2017), pp. 55–68.

- Ramón Michel et al. (see note 6).

- Ministerio de Salud de la Nación, Protocolo integral de atención a personas con derecho a la interrupción legal del embarazo (updated version, 2015). Available at http://www.msal.gob.ar/images/stories/bes/graficos/0000000875cnt-protocolo_ile_octubre%202016.pdf; Fallo F., A. L. s/medida autosatisfactiva (Argentina, Corte Suprema de Justicia, March 13, 2012).

- Ministerio de Salud de la Provincia de Santa Fe, Resolución 843/2010 (2010); Ministerio de Salud de la Provincia de Mendoza, Resolución 933/2011 (2011); Cámara de Diputados de la Provincia de San Luis, Act No. I-0650-2008 (2008).

- E. Azarkevich, “Aborto: Anticipan que todos los médicos de un hospital de Misiones apelarían a la objeción de conciencia,” Clarín (June 16, 2018). Available at http://www.clarin.com/sociedad/aborto-anticipan-medicos-hospital-misiones-apelarian-objecion-conciencia_0_Hk336AMWX.html; S. Deza, “Objeción de conciencia frente al aborto en Tucumán: Herramienta de mayorías,” Jaque a la reina: Salud, autonomía y libertad reproductiva en Tucumán (Buenos Aires: Ed. Cienflores, 2014); J. M. Vaggione, “La política del camuflaje: La objeción de conciencia como estrategia de la Iglesia Católica,” Emisférica 13/1 (2016).

- “1600 médicos riojanos rechazan el aborto legal, seguro y gratuito,” La Rioja Virtual (May 28, 2019). Available at http://riojavirtual.com.ar/1600-medicos-riojanos-rechazan-el-proyecto-de-aborto-legal-seguro-y-gratuito/; “Chaco: Domingo Peppo vetó ley sobre aborto no punible a dos días de las elecciones,” Ambito.com (October 11, 2019). Available at http://www.ambito.com/chaco-domingo-peppo-veto-ley-aborto-no-punible-dos-dias-las-elecciones-n5059481; “Clínicas, sanatorios y hospitales de las privadas exigen libertad para no practicar abortos,” Chaco Hoy (July 27, 2018). Available at http://www.chacohoy.com/inicio/basicamovil/126785; Azarkevich (see note 14); “Imaginate, nos ponen en una controversia,” Página 12 (June 16, 2018). Available at http://www.pagina12.com.ar/121918-imaginate-nos-ponen-en-una-controversia; “Más de 200 nenas violadas fueron obligadas a parir en Misiones,” TN (July 2, 2017). Available at http://tn.com.ar/sociedad/201-ninas-violadas-obligadas-parir-en-misiones_879741; “‘El 90% del personal de salud no va a hacer abortos’: Fuerte advertencia de médicos del Chaco,” Infobae (July 4, 2018). Available at http://www.infobae.com/politica/2018/07/04/el-90-del-personal-de-salud-no-va-a-hacer-abortos-fuerte-advertencia-de-medicos-del-chaco; “En La Rioja, una cantidad abrumadora de médicos rechazan el aborto,” Via País (May 29, 2018). Available at http://viapais.com.ar/la-rioja/1052180-en-la-rioja-una-cantidad-abrumadora-de-medicos-rechazan-el-aborto; “ILE: Sólo 3 médicos del Lago no son objetores de conciencia,” El Sol (March 22, 2019). Available at http://www.elsol.com.ar/aborto-no-punible-solo-tres-medicos-del-lago-no-son-objetores-de-conciencia; “Más trabas para el acceso al aborto legal en La Pampa,” El Diario de La Pampa (May 26, 2018). Available at http://www.eldiariodelapampa.com.ar/index.php/112-portada/cuater/44719-mas-complicaciones-para-el-acceso-al-aborto-legal-en-la-pampa.

- “Tucumán: Amenazan a una médica que le realizó un aborto a una nena que fue violada,” Perfil (July 8, 2018). Available at http://www.perfil.com/noticias/sociedad/tucuman-amenazan-a-una-medica-que-realizo-un-aborto-a-una-nena-abusada.phtml.

- See M. Carbajal, “La ‘falta grave’ de no respetar la ley,” Pagina 12 (September 11, 2014). Available at http://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/sociedad/3-255024-2014-09-11.html; see “Sancionan a una psicóloga por obstaculizar un aborto terapéutico a una niña de 11 años,” Pausa Periódico Digital (April 27, 2017). Available at http://www.pausa.com.ar/2017/04/sancionan-a-una-psicologa-por-obstaculizar-un-aborto-terapeutico-a-una-nina-de-11-anos/.

- Fiala et al. (see note 4).

- B. Johnson Jr., E. Kismödi, M. V. Dragoman, and M. Temmerman, “Conscientious objection to provision of legal abortion care,” International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics123 (2013), pp. S60–S62; W. Chavkin, L. Leitman, and K. Polin, “Conscientious objection and refusal to provide reproductive healthcare: A white paper examining prevalence, health consequences, and policy responses,” International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics123 (2013), pp. S41–S56.

- S. Ariza Navarrete, “Objeción de conciencia en el mundo: Estudio comparado de regulaciones,” in M. Alegre (ed), Libres e iguales: Estudios sobre autonomía, género y religión (Mexico: UNAM, 2019).

- S. Ariza Navarrete, B. Kohen, and A. Ramón Michel, “Investigación sobre el registro de objeción de conciencia en Santa Fe” (Buenos Aires: Mimeo, 2020); “Aborto: Objetores a otra parte,” El Ciudadano (August 7, 2010). Available at http://www.elciudadanoweb.com/aborto-objetores-a-otra-parte/; “En marzo cierra el registro de los médicos objetores,” El Ciudadano (January 23, 2011). Available at http://www.elciudadanoweb.com/en-marzo-cierra-el-registro-de-los-medicos-%E2%80%9Cobjetores%E2%80%9D/; “Objetores médicos contra abortos legales,” El Ciudadano (May 28, 2014). Available at http://www.elciudadanoweb.com/se-presento-un-registro-de-objetores-medicos-contra-abortos-legales/.

- Magelssen et al. (see note 1).

- Chavkin et al. (2013, see note 16).

- “Tucumán: Amenazan a una médica…” (see note 16); “En primera persona: El relato del médico que intervino a la nena de Tucumán,” La Voz (February 28, 2019). Available at http://www.lavoz.com.ar/ciudadanos/en-primera-persona-relato-del-medico-que-intervino-nena-de-tucuman; “Tucumán: Denunciaron a los médicos que le hicieron la cesárea a la nena de 11 años violada,” TN (March 11, 2019). Available at http://tn.com.ar/sociedad/tucuman-denunciaron-los-medicos-que-le-hicieron-la-cesarea-la-nena-de-11-anos-violada_946343; “Médicos ‘provida’ denunciaron al hospital donde se hizo el aborto a la nena violada,” TN (August 27, 2018). Available at http://tn.com.ar/sociedad/medicos-provida-denunciaron-al-hospital-rawson-donde-se-hizo-el-aborto-la-nena-violada-en-san-juan_892919; “El hospital de niños salió a cruzar a médica pro aborto legal,” La Rioja Virtual (July 17,2018). Available at http://riojavirtual.com.ar/el-hospital-de-ninos-salio-a-cruzar-a-medica-pro-aborto-legal/.

- D. Szulik and N. Zamberlin, “Percepciones de los profesionales de la salud sobre el estigma relacionado a la práctica de aborto no unible en el contexto argentino,” 3ra. Conferencia Subregional del Cono Sur (2015). Available at http://clacaidigital.info/handle/123456789/712.

- F. Hanschmidt, K. Linde, A. Hilbert, et al., “Abortion stigma: A systematic review,” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 48/4 (2016), pp. 169–177; L. A. Martin, J. A. Hassinger, et al., “Evaluation of abortion stigma in the workforce: Development of the revised Abortion Providers Stigma Scale,” Women’s Health Issues 28/1 (2018), pp. 59–67.

- L. H. Harris, L. Martin, M. Debbink, and J. Hassinger, “Physicians, abortion provision and the legitimacy paradox,” Contraception 87/1 (2013), pp. 11–16.

- Martín et al. (see note 23).

- Fiala et al. (see note 4).

- Ariza Navarrete (see note 21); Chavkin et al. (2013, see note 2); C. Zampas, “Legal and ethical standards for protecting women’s human rights and the practice of conscientious objection in reproductive healthcare settings,” International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 123 (2013), pp. S63–S65; Chavkin et al. (2017, see note 8).

- Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Access to information on reproductive health from a human rights perspective, OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 61 (2011).

- Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales, Derechos humanos en la Argentina: Informe 2017 (Buenos Aires: Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales, 2017); Asociación por los Derechos Civiles, Acceso al aborto no punible en Argentina: Estado de situación, marzo 2015 (Buenos Aires: Asociación por los Derechos Civiles, 2015); Amnistía Internacional Argentina, El acceso al aborto en Argentina: Una deuda pendiente (Buenos Aires: Amnistía Internacional Argentina, 2018); B. A. Autorización Judicial (Argentina, Corte Suprema de Justicia, case Ac.82.058, June 22, 2001); A. G s/Medida autosatisfactiva (Argentina, Corte Suprema de la Provincia de Chubut, March 8, 2010); Fallo F., A. L. s/medida autosatisfactiva (see note 12).

- W. Chavkin, L. Swerdlow, and J. Fifield, “Regulation of conscientious objection to abortion: An international comparative multiple-case study,” Health and Human Rights Journal 19/1 (2017), p. 55.

- C. A. O’Reilly, D. F. Caldwell, J. A. Chatman, et al., “How leadership matters: The effects of leaders’ alignment on strategy implementation,” Leadership Quarterly 21/1 (2010), pp. 104–113; C. F. Jensema, The relationship of moral sensitivity to leadership behaviors: An investigation of Catholic healthcare, PhD thesis, Marian University (2012); J. Cortés González, M. P. Hernández Saavedra, T. G. Marchena Rivera, et al., “Estilos de liderazgo en jefes de Servicio de Enfermería,” Revista de Enfermería Neurológica 12/2 (2013), pp. 84–94.

- Amnistía Internacional Argentina, Católicas por el Derecho a Decidir, Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales, and Equipo Latinoamericano de Justicia y Género, “El derecho a la salud sexual y reproductiva de las mujeres en Argentina,” civil society document submitted to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, May 2018).

- See R. Triviño Caballero, El peso de la conciencia: La objeción en el ejercicio de las profesiones sanitarias (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2014), pp. 263–284; A. Lipp, “A review of termination of pregnancy: Prevalent health care professional attitudes and ways of influecing them,” Journal of Clinical Nursing 17/13 (2008), pp. 1683–1688; E. Espey, T. Ogburn, and F. Dorman, “Students’ attitudes about a clinical experience in abortion care during the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship,” Academic Medicine 79/1 (2004), pp. 96–100.

- S. Murphy and S. J. Genuis. “Freedom of conscience in health care: Distinctions and limits,” Journal of Bioethical Inquiry10/3 (2013), pp. 347–354; V. D. Lachman, “Conscientious objection in nursing: Definition and criteria for acceptance,” MedSurg Nursing23/3 (2014), p. 196; C. E. Vaiani, “Personal conscience and the problem of moral certitude,” Nursing Clinics 44/4 (2009), pp. 407–414; C. A. LaSala, “Moral accountability and integrity in nursing practice,” Nursing Clinics 44/4 (2009), pp. 423–434.