Health for All? Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and the Implementation of the Right to Access to Health Care in South Africa

Alexandra Müller

Abstract

The framework of health and human rights provides for a comprehensive theoretical and practical application of general human rights principles in health care contexts that include the well-being of patients, providers, and other individuals within health care. This is particularly important for sexual and gender minority individuals, who experience historical and contemporary systematical marginalization, exclusion, and discrimination in health care contexts. In this paper, I present two case studies from South Africa to (1) highlight the conflicts that arise when sexual and gender minority individuals seek access to a heteronormative health system; (2) discuss the international, regional, and national human rights legal framework as it pertains to sexual orientation, gender identity, and health; and (3) analyze the gap between legislative frameworks that offer protection from discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity and their actual implementation in health service provision. These case studies highlight the complex and intersecting discrimination and marginalization that sexual and gender minority individuals face in health care in this particular context. The issues raised in the case studies are not unique to South Africa, however; and the human rights concerns illustrated therein, particularly around the right to health, have wide resonance in other geographical and social contexts.

Introduction

In all regions, people experience violence and discrimination because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. In many cases, even the perception of homosexuality or transgender identity puts people at risk. Violations include—but are not limited to—killings, rape and physical attacks, torture, arbitrary detention, the denial of rights to assembly, expression and information, and discrimination in employment, health and education.1

Sexual and gender minority individuals in health care

Evidence from around the world highlights that sexual and gender minority patients experience discrimination, stigmatization, and even denial of care in the health system due to their sexual orientation and gender identity. Those grouped as “sexual and gender minorities,” however, do not constitute a homogenous group, and social exclusion, marginalization, and experiences of discrimination, as well as specific health needs, vary considerably. Differences between lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) individuals (sexual minorities) and transgender, gender non-conforming, and gender-diverse individuals (gender minorities) are significant. However, the minority status of all individuals within this broad group, as well as social exclusion, discrimination, marginalization, and violence, is, for each of them, rooted in societal heteronormativity: society’s pervasive bias toward the gender binary and opposite-gender relationships, which marginalizes and excludes all non-heteronormative sexual (LGB) and gender (T) identities. For this reason, I purposefully employ the term “sexual and gender minorities,” instead of LGBT, to emphasize their minority status and the common source of oppression, while acknowledging that this oppression acts on different identities (sexual orientation or gender) in different ways. These are even more heterogeneous when taking other forms of oppression, such as race, ethnicity, gender, (dis)ability, and nationality into account.

There is great potential in applying health and human rights frameworks to analyzing the instances of discrimination, marginalization, and exclusion faced by sexual and gender minority individuals in health care contexts. Analyses of sexuality, including sexual orientation, in health and human rights, however, are relatively novel: before the 1993 World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna, and the subsequent 1994 International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo, sexuality, sexual rights, and sexual diversity had not formed part of the international health and human rights discourse.2 These newly emerged “sexual rights” were founded on the principles of bodily integrity, personhood, equality, and diversity.3 In the past two decades, emergent scholarship has tackled the complex issues of sexuality, sexual agency, sexual diversity, and sexual violence within a health and human rights framework, which includes a focus on sexual orientation and gender identity, and, thus, on sexual and gender minority individuals.4 Analyses that employ a health and human rights framework to analyze specific experiences of sexual and gender minority individuals in health care, however, remain rare—even more so in contexts outside of Europe and North America, even though the exclusion, marginalization, and discrimination of sexual and gender minority individuals in health care is increasingly well documented. For example, in a Canadian study, Brotman and colleagues found that being open about their sexual orientation in health care settings contributed to experiences of discrimination for lesbian, gay, and bisexual people.5 In South Africa, an emerging body of literature documents health system bias against sexual and gender minorities: for example, Lane and colleagues interviewed men who have sex with men in Soweto, and revealed that all men who disclosed their sexual orientation at public health facilities had experienced some form of discrimination.6 Such discrimination, and also the anticipation thereof, leads to delays when seeking sexual health services such as HIV counseling and testing.7 Gender minority individuals, who are recognized as a key “at risk” group due to socio-economic marginalization and exclusion, and who experience high levels of violence because of such marginalization and gender non-conformity, encounter multiple layers of discrimination in South African health care facilities, ranging from verbal abuse to denial of care.8

It is crucial to note that such discrimination is not only perpetrated by individual health care providers, but is deeply rooted in the health system itself. Historically, medical research produced the “scientific” evidence to support powerful normative, discriminatory beliefs pertaining to gender, sex, sexuality, and identity, and was thus deeply prohibitive of non-conforming sexualities and gender identities.9 Until 1973, homosexuality was considered a mental illness and listed as such in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), indicating the consensus of psychiatry at the time that sexual and romantic attraction to somebody of the same sex was unnatural, pathological, and could be cured through psychotherapy or electro-shock aversion therapy.10 Until 1992, it was listed as a diagnosis in WHO’s International Classification of Disease.11

Gender identity disorder, the diagnosis for feeling that one’s assigned sex at birth does not match one’s felt gender identity, remains a classification both in the DSM as well as in the current ICD-10, and is pervasively used in relation to transgender people.12 While such a diagnostic classification might be needed to facilitate access to gender-affirming treatment, many transgender interest groups have pointed out that it also further pathologizes and stigmatizes gender non-conforming identities.13 In a recent report, the UN Special Rapporteur on torture recognized the particular vulnerability of marginalized groups to torture and ill-treatment in health settings, citing “[s]tructural inequalities, such as the power imbalance between doctors and patients, exacerbated by stigma and discrimination.” 14

The impact of social exclusion, discrimination, and stigmatization on the health of sexual and gender minority people has been increasingly well documented over the past decade.15 Sexual and gender minority populations have a higher prevalence of mental health concerns, including suicide ideation and attempts, depression, and anxiety disorders.16 Lesbian women and transgender people, especially those living in poor socioeconomic circumstances, are more vulnerable to HIV infection than socio-economically matched heterosexual and cisgender peers. A recent study from southern Africa showed that one-third of 591 participating women who had sex with women had experienced sexual violence, demonstrating HIV risk for a population previously considered exempt; moreover, there was a 10% self-reported rate of living with HIV.17

In light of the impact that social and economic exclusion, violence, and minority stress due to discrimination and stigmatization have on the health of sexual and gender minorities, it has been suggested that sexual orientation and gender identity should be recognized as a social determinant of health, much like gender, socio-economic status, and others.18 Similarly, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has emphasized that homophobia (the irrational fear of and hatred of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people) should be considered as significant and comparable to sexism, racism, or xenophobia.19

Not only sexual and gender minority patients are impacted by heteronormativity and homophobia in the health systems. Accounts of health care providers who openly identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender point to ongoing stigma and discrimination within the health care profession and health professions education.20 For example, 62% of medical students across 92 US medical institutions reported exposure to anti-gay comments.21 In a survey of sexual and gender minority physicians, 22% reported that they had been socially ostracized, 65% had heard derogatory comments about sexual and gender minority individuals, and 34% had witnessed discriminatory care of a sexual or gender minority patient.22

Provisions of civil, social, economic, and political rights for sexual and gender minorities in the context of health care

More recent international provisions for the right to the highest attainable standard of health acknowledge the impact that social and economic discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity have on access to and quality of health care. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) makes no mention of these two markers, likely due to the time of its drafting and adoption in 1954 and 1966, respectively, but lists a number of “other statuses” that can lead to discrimination.23 Paragraph 32 of General Comment 20 on non-discrimination in economic, social, and cultural rights (2009), specifies that “other status” includes sexual orientation and that “states parties should ensure that a person’s sexual orientation is not a barrier to realising Covenant rights.”24 Paragraph 12.b of General Comment 14 (2000), which operationalizes the right to health, states that non-discrimination is a key dimension of accessibility to health care; and paragraph 18 of General Comment 14 elaborates that Article 2.2 and Article 3 of the Covenant proscribe “any discrimination in access to health care and underlying determinants of health, as well as to means and entitlements for their procurement, on the grounds of […] sexual orientation […] which has the intention or effect of nullifying or impairing the equal enjoyment or exercise of the right to health” (italics added for emphasis).25

The health and human rights framework for sexual and gender minority individuals in South Africa

The South African Constitution (1996) has one of the strongest provisions on the right to health worldwide. The right to health is covered under Article 27, together with rights to food, water, and social security.26 Article 27(a) provides that everyone has the “right to access health care, including sexual and reproductive health care.” Further sections provide for the right to sufficient food and water and social security, including appropriate social assistance if people are unable to support themselves and their dependents. Article 27 requires the state to take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, to achieve the progressive realization of each of these rights. These constitutional provisions have been employed previously to force the state to provide antiretroviral treatment for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV.27 After a 20-year campaign, South Africa finally ratified the ICESCR in early 2015.

Two additional documents specifically outline patients’ rights. The South African Patients’ Rights Charter, specific to health care contexts, and the Batho Pele Principles (meaning “People First”) that are applicable for all public services provided by the South African government.28

South Africa’s constitutional and legislative framework for sexual and gender minorities is among the most progressive globally. The constitution provides that the state is obliged to “respect, protect, promote and fulfill” the rights enshrined in the Bill of Rights.29 Central to the Bill of Rights is the Equality Clause in Section 9, which mandates that nobody may be discriminated against based on, among other grounds, their sex, gender, or sexual orientation. Section 10 guarantees that everyone has inherent dignity and the right to have their dignity respected and protected.

Further rights enumerated in the Bill of Rights include the right to life (Section 11), as well as the right to security of the person, including the right “to be free from all forms of violence from either public or private sources,” the right “to security in and control over their body,” and the right “not to be treated or punished in a cruel, inhuman or degrading way” (Section 12).

Emanating from this constitutional mandate, sexual and gender minority individuals enjoy a range of civil rights in the country. A range of legislative and policy reforms after 1996 have sought to remove laws drafted under apartheid that criminalized or discriminated against sexual and gender minorities, of which I will only list those pertaining to health and access to health care. The Medical Schemes Act of 1998 defines “dependent” to include same-sex partners and therefore extends medical insurance benefits to same-sex partners; the Domestic Violence Act of 1998 expands the definition of domestic relationships to recognize cohabitation by unmarried people including same-sex couples; and the Refugees Act of 1998 recognizes gender and sexual orientation as grounds for persecution and, thus, for seeking asylum in South Africa.30 In 2006, the president of South Africa signed into law the Civil Union Act, which recognizes “the voluntary union of two persons […] registered by way of either a marriage or a civil partnership,” and therefore guarantees marriage equality to same-sex couples.31

The progressive and protective South African legal framework is unique on the African continent. While two other countries in the southern African region (Lesotho, and, in 2015, Mozambique) have decriminalized same-sex activity, the laws of most African countries hold provisions that outlaw same-sex activity, which are usually remnants of British colonial law.32 There are vast differences in the enforcement and consequences of these laws across African countries, ranging from the death penalty to what Epprecht calls a “de facto culture of tolerance […], notwithstanding sometimes harsh laws and elite homophobic rhetoric” (emphasis in original).33 In recent years, public health arguments that seek to reduce the impact of HIV on criminalized populations, such as men who have sex with men, have resulted in slow and careful shifts in attitude and approach.34 For example, in 2014, the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights passed Resolution 275, which

strongly urges States to end all acts of violence and abuse, whether committed by State of non-state actors, including by enacting and effectively applying appropriate laws prohibiting and punishing all forms of violence including those targeting persons on the basis of their imputed or real sexual orientation or gender identities, ensuring proper investigation and diligent prosecution of perpetrators, and establishing judicial procedures responsive to the needs of victims.35

Despite these high-level shifts, homophobic and transphobic violence, persecution, and state repression remain a threat to the health and safety of sexual and gender minority individuals in many African countries.36 It is noteworthy that even in South Africa, the progressive and affirming stance of the constitution towards sexual and gender minority people is not reflected in the dominant attitudes in South African society; statements by public figures indicate that deeply conservative views about gender and sexuality prevail.37 For example, in 2010 Jerry Matjila, South Africa’s then-representative at the United Nations, objected to the inclusion of sexual orientation in a report on racism at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva. He argued that to include sexual orientation would be to “demean the legitimate plight of the victims of racism.”38

In the following two case studies, I explore the experiences of Thabo (a pseudonym), a young gay man, and Palesa (also a pseudonym), a young lesbian woman, in two different health facilities in South Africa. In doing so, I (1) highlight the conflicts that arise when sexual and gender minority individuals seek access to a heteronormative health system; (2) discuss the international, regional, and national human rights legal framework as it pertains to sexual orientation, gender identity, and health; and (3) analyze the gap between legislative frameworks that offer protection from discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity and the their actual implementation in health service provision.

The narratives from these case studies are taken from a larger, cross-sectional, qualitative study on sexual and gender minority peoples’ experiences in public health care, of which I was the principal investigator.39 Both case studies use pseudonyms to preserve the participants’ anonymity. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Cape Town (HREC: 033/2013), and individual research participants gave their permission for their anonymized data to be published in academic literature.

Case study one: Thabo

Thabo’s story

Thabo is a young black gay man living in a peri-urban township near Pretoria, which is one of the three capital cities of South Africa. He attends the local technical university that provides students with an applied education to enter into specialized positions in the labor market. Thabo is out to the majority of people in his life, including his mother, with whom he still lives; and he regularly attends events of the LGBTI student group on his campus. He describes himself as “a flamboyant queen,” and expresses his gender identity in a feminine, non-conforming way. When I interviewed him in April 2013 about his experiences using public health facilities, he told me about an admission to the nearest district hospital after being pursued by a group of men in a homophobic attack, during the course of which he broke both his arms when trying to escape by jumping from a second-floor balcony. He was taken to the emergency room by a friend (ambulances often take a long time to reach patients living in townships), where he eventually recounted the story after being asked numerous times by the nurse on duty.

He included the homophobic motivation of his attackers, and thereby effectively disclosed his sexual orientation. The nurse told him that he “got what he deserved,” and when he was transferred to the ward to await further surgical treatment, he discovered that she had told the ward nurses on duty about his sexual orientation. This information was passed on to nurses on later shifts, such that throughout his three-day stay he felt singled out, could discern the nurses’ disparaging attitudes towards him, and was frequently the source of hospital gossip, including when he was present. A local prayer group that visited the ward daily to provide spiritual support to patients prayed at his bedside to rectify his “devious” sexuality. When he requested that they leave, or that he be transferred to another ward to be out of their reach, the nurses did not intervene, and the prayer group visited regularly to continue the homophobic prayers.

He did not appear to know about the Batho Pele principles, and did not lodge a complaint about the discriminatory treatment he received because he was scared of the negative ramifications this might have on his ability to access treatment at the facility in future. After he had had surgery for both his arms, he was discharged. He did not return for any follow-up appointments, and chose to have his casts removed at a different primary care facility where nobody knew him.

Analysis

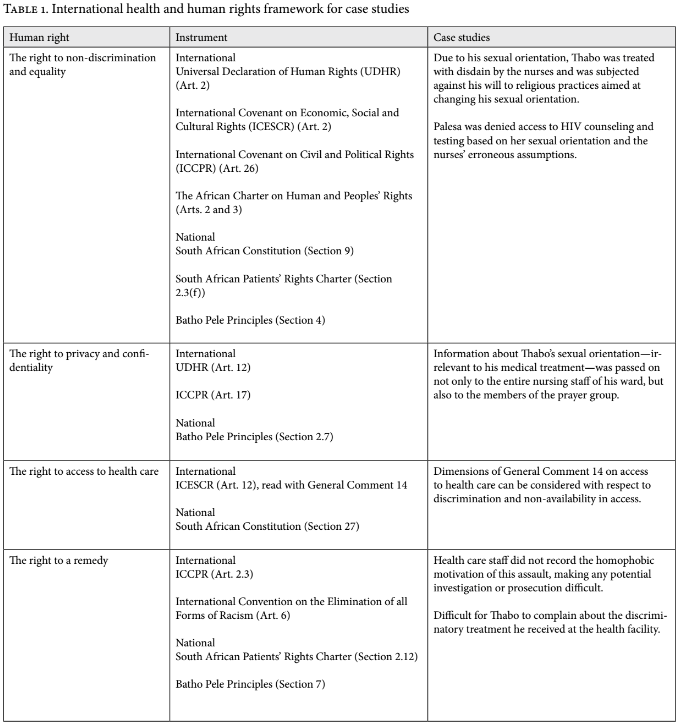

Using a right to health framework to analyze Thabo’s story, the right to non-discrimination in access to health care (paragraph 12.b and paragraph 18 of General Comment 14) seems immediately relevant, as well as the provisions of the South African Patients’ Rights Charter and the Batho Pele Principles for all public services in South Africa.40 However, this framework does not suffice to thoroughly analyze the homophobic discrimination and judgment that Thabo experienced, as well as the failure to recognize his attack as a homophobic hate crime. Cohen and Ezer write that “Even the basic right of access […] benefits from the lens of human rights and its focus on non-discrimination and equality.”41 Drawing on such a comprehensive human rights framework allows the recognition of a number of Thabo’s rights that were violated during his stay at the health facility. These are outlined in Table 1.

It is important to analyze Thabo’s experience through an intersectional framework. Intersectionality (the ways in which different social identities are enmeshed) aims to understand the “simultaneity of interlocking systems of oppression”, by, for example, race, class, gender, sexual orientation and ability, in the experience of individuals.42 In Thabo’s case, it provides an important context for understanding factors of vulnerability to violence and discrimination. The South African health care system is highly unequal, with an under-resourced public health system that caters for up to 80% of the population at a cost relative to patients’ income, and a well-resourced private health system whose cost prohibits all but about 16% of the population from using it.43 Access to health care is therefore highly dependent on class, race, and geographical location, given the unequal distribution of wealth and income in the country due to centuries of colonialism and the apartheid system.44

In Thabo’s case, accessing the private health system was not an option given his limited financial capacity. Thabo’s race also significantly influenced his experience of homophobia, both as the reason for seeking health care, and within the health system. In South Africa, there exists considerably more violence against sexual and gender minority persons of color, in particular against visibly gender non-conforming people.45 Homophobic sexual violence against black lesbian women (often problematically termed “corrective rape”) has been documented increasingly since the early 2000s, and there are significantly more cases of hate crimes against gay men of color than white gay men.46 This points to complex vulnerabilities shaped by race, gender, and class, and highlights the fact that gender non-conforming people of color are at significantly higher risk of experiencing homophobic violence.

Thabo’s experience of the health facility as an unsafe and discriminatory space is not unusual. As mentioned above, an emerging body of literature confirms that sexual and gender minority patients are routinely discriminated against, ridiculed, or even denied services by health care providers, in disregard of the protective legislative provisions in the South African constitution and their related policies.47 This is not unique to sexual and gender minority patients. Evidence on nurses’ decision-making can help to illuminate some of the reasons behind the discriminatory behavior exhibited by health care providers in Thabo’s case. First, studies with South African nurses providing sexual and reproductive health services to adolescents show that health care providers base their service delivery on their own values and their perceived ‘moral worth’ of a patient.48 By using their discretion, they effectively re-interpret—and sometimes ignore—law and policy, and trade it for their own moral judgment, which is more likely to be the case if the patient, or the health issue at hand, is perceived as controversial or morally ‘charged.’

Given that the majority of South Africans (61%) consider homosexuality to be ‘not acceptable,’ it is more than likely that many health care providers also share discriminatory views of sexual and gender minority patients.49 Second, bias against sexual and gender minority individuals remains high within the health system. Fallin-Bennett recently commented on how the widespread ‘implicit bias’ that physicians teaching in medical education hold against sexual and gender minority individuals can ‘create a cycle that perpetuates a professional climate reinforcing the bias.’50 Role modeling is an important way through which attitudes and behaviors are fostered in health service delivery.51 This can not only provide a climate of acceptance for sexual and gender minority discriminatory behavior, but also create pressure for health care providers who are sympathetic to conform to conservative and discriminatory norms.

A more structural analysis of Thabo’s experience underscores that while health rights violations are usually perpetrated by individual health care providers, they are also steeped in a system that tacitly tolerates such discriminatory behavior. For example, there are no policies either at health facility level or within institutions of health professions education that recognize sexual orientation or gender identity as grounds for discrimination and offer protection thereof, leaving little or no possibility for recourse for sexual and gender minority patients and health care providers who experience such discrimination. Existing general complaint policies require patients to complain within the same facility that discrimination occurred. As Thabo’s case shows, patients are often reluctant to follow this policy and previous research from South Africa confirms that only between 6% and 29% of health service users would actually make a complaint.52 While newer complaints mechanisms have been set up in recent years, including a toll-free hotline by the Department of Health, such options are likely to not seem like viable options to sexual and gender minority individuals who have come to expect homophobic discrimination at all levels of the health system.53 Often, the perception of further victimization, or of future negative consequences at facility level, acts as deterrent to lodging a complaint.

A potential solution could be to take such cases to one of the high-level oversight bodies established to monitor professional conduct, for example, the Health Professions Council of South Africa (which registers all medical practitioners), the Nursing Council of South Africa, or the Human Rights Commission. Such a decision, however, requires not only a thorough knowledge of the existence, mandate, and working of these bodies, but also financial resources and networks that most South Africans who use public health care do not possess. While media exposure of malpractice and poor health service delivery has increased the attention on the quality of services provided, none of the profiled instances has focused on sexual orientation or gender identity-related discrimination yet. Further, no case of health care discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation or gender identity in health care has been brought to any of the professional oversight bodies, or to any level of the judiciary.

An intersectional analysis allows us to tease out the complex dynamics that play out in the implementation of the right to access to health care, that result not only in easily measurable indicators such as access, but also in the interpersonal relations between sexual and gender minority patients and health care providers. In such complex ‘messy’ situations, the framework of human rights in patient care seems to be more adept at capturing the complexity of these encounters, and to analyze the more subtle experiences of marginalization and exclusion that patients like Thabo encounter.

Case study two: Palesa

Palesa’s story

Palesa is a young black lesbian woman who I interviewed in May 2013. She had recently finished her undergraduate university degree, and at the time of our interview, lived in a student area in Cape Town and worked as a waitress in a restaurant. Palesa exclusively has sexual and romantic relationships with women, but she does not conform to a ‘typical lesbian’ image, and, as she told me, often passes as heterosexual with people who do not know her well. Palesa wanted to go for an HIV test after she had met her current partner of three years, in order for her and her then-new partner to make informed decisions about their sexual health behavior. She decided to go to the local public primary health facility, which she had visited previously for various health concerns. During these visits, her sexual orientation had never come up, and she did not see the need to disclose it to the health care providers. When she went for her session of voluntary HIV counseling and testing, the nurse began by going through the pre-test questionnaire, aimed at identifying HIV risk behaviors that could be addressed in the post-test counseling session.

When Palesa—prompted by the questionnaire—said that she was sexually active but was not using condoms or contraception, the nurse checked a number of boxes on her questionnaire in quick succession. When the nurse asked her why she was not using condoms, Palesa hesitated briefly, realizing that in answering this question she either needed to disclose her sexual orientation or lie, and then told the nurse that she only had sex with women. Without asking any further questions, the nurse exclaimed that Palesa was not at risk for HIV, and that she should go home and not waste her time any longer. Palesa was taken aback, and left the clinic quickly. She has not attempted to have another HIV test since.

Analysis

As with Thabo’s case study, Palesa’s narrative can be analyzed by focusing on the right to accessing health care. The nurse’s refusal to offer her an HIV test is a clear violation of the right to access health care (Art. 27(a) of the South African Constitution), as well as discrimination in health care accessibility (Section 12.b of General Comment 14). As with Thabo’s case, however, a more thorough analysis of the human rights in this patient care situation is useful to tease out the nuanced rights violations, taking into account the health and human rights framework in Table 1.

Unlike Thabo, the violations of Palesa’s rights were not caused by her visible non-conformity to heteronormativity. Rather, the nurse’s denial of an HIV test for Palesa was borne out of her erroneous assumption that women who have sex with women are not at risk for HIV, coupled with her inability to adequately inquire about sexual health behavior and risk behavior in Palesa’s case. Emerging research points out that one-third of women who have sex with women in Southern Africa have experienced sexual violence, and that this is a significant risk factor for HIV.54 These findings clearly contradict the nurse’s erroneous perception of Palesa not being at risk for HIV, and also underline that there are crucial follow-up questions to be asked when a patient discloses same-sex activity (for example, inquiring about sexual relationships with people of the opposite sex and experiences of sexual violence). This lack of competency is due to the invisibility of non-conforming sexual orientations and gender identities in health system policies, planning, and services, as well as in health professions education. Unlike Thabo, therefore, Palesa’s discrimination was not rooted in negative and discriminatory attitudes, but rather in ignorance about the specific health concerns of lesbian women.

In South Africa, health professions education does not address routinely the social determinants of health, contextual vulnerabilities, and specific health needs of sexual and gender minorities.55 As a result, health care providers are often ill-equipped to provide quality care to sexual and gender minority patients. While studies from other contexts have shown that health care students who received training on sexual and gender minority health-related topics had better knowledge and were more confident with sexual and gender minority patients, student nurses and doctors in South Africa are currently not provided with these competencies.56 Further, it has been shown that while the formal curriculum is important, it is not the only influence that determines health profession students’ competence for providing care to sexual and gender minority patients. The hidden curriculum—a term used to describe the implicit, often highly gendered, and discriminatory values that are taught to students in institutionalized education settings—plays a crucial role in teaching students about institutional values, institutional climate, and implicit assumptions about worth within the health care and medical education system.57 Studies on the experiences of sexual and gender minority students in South African health sciences faculties suggest that the influence of the hidden curriculum is as strong in this context as elsewhere, and contributes to the marginalization of sexual and gender minority individuals and their health concerns.58

Using a human rights-based framework can help to identify the consequences of the invisibility of such topics in health professions education. This, in turn, can support efforts to name and address this invisibility, and advocate for an understanding of sexual orientation and gender identity as social determinants of health, and the inclusion of sexual and gender minority health in health professions education and continuous professional development courses.59

Discussion and conclusion

The framework of human rights in health care provides a useful lens for analyzing rights abuses in health settings, in that it places patients at the center, focuses attention on discrimination and social exclusion, and zooms out from the individual patient-provider relationship to examine systemic issues and state responsibility.60 In this article, I have demonstrated the application of this framework to analyze discrimination due to sexual orientation and gender identity in the South African public health system. As the case studies illustrate, the progressive equality legislation around sexual orientation and gender identity in South Africa is not necessarily a predictor for the successful implementation of the right to access to health care for sexual and gender minority patients. The case studies therefore highlight two important issues:

- The need to recognize sexual orientation and gender identity as causes for human rights violations in health care; and

- The need to analyze such rights violations through a comprehensive human rights framework that takes into account the various intersecting marginalizations that people experience.

As the case studies demonstrate, the human rights violations that both Thabo and Palesa experienced were perpetrated by individuals, but were indicative of larger systemic issues of homophobia and invisibility. The lack of responsive complaint mechanisms, combined with the lack of training and knowledge about sexual and gender minority health, missed opportunities for values clarification training, and the complexities of health care providers’ decision-making perpetuates the marginalization and invisibility of sexual and gender minority patients in the health system. As a result, even when protective policies do exist, they are not implemented adequately.

While the South African Constitution offers some of the best protection to sexual and gender minority individuals, there is a gap between constitutional protection and the reality of health care provision. In other countries, homosexuality, transgender identities, and/ or same-sex practices are criminalized.61 The UN High Commissioner on Human Rights highlights that “the criminalization of homosexuality may deter individuals from seeking health services for fear of revealing criminal conduct, and results in services, national health plans and policies not reflecting the specific needs of LGBT persons.”lxii The Special Rapporteur on Health echoes these observations and notes that, “Criminal laws concerning consensual same-sex conduct, sexual orientation and gender identity often infringe on various human rights, including the right to health.”63

Considering the impact of such criminalizing legislation on health care access underlines the need for taking sexual orientation and gender identity into account when analyzing human rights in health and patient care. The Yogyakarta Principles on the Application of International Human Rights Law in relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, which illustrate the application of human rights law to issues of sexual orientation and gender identity, can provide a useful tool for including sexual orientation and gender identity in such analyses of health and human rights.64 There is, however, considerable debate for and against such a compartmentalization of sexual and gender minority rights.65 Further there is a vast difference in the understanding of the term ‘sexual rights,’ which supposedly encapsulates these rights.66

While a detailed discussion of the implications of these tensions is beyond the scope of this article, the geographical, historical, social, and political specificity of sexual and gender minority rights claims needs to be acknowledged and considered. South Africa’s unique progressive position with regards to sexual and gender minority rights places the country in a unique position to negotiate the necessity of such rights without defaulting to the claim of universality, which is often the political reason for other African countries to reject sexual and gender minority rights.67 The carefully articulated public health-motivated arguments for sexual and gender minority rights currently emerging across many African countries are an important example of context-specific, health-based rights claims for sexual and gender minority individuals.

In summary, in this article I have reviewed the international provisions around health and human rights for sexual and gender minority patients. I have presented two case studies from South Africa, which examine the divergence between the law and policy framework and its implementation, and stress the necessity for including a focus on sexual orientation and gender identity in analyzing human rights in health and patient care. These case studies highlight the complex and intersecting discrimination and marginalization that sexual and gender minority individuals face when accessing care in a historically and epistemologically deeply heteronormative health system. In my conclusion, I point to the importance of challenging state-sponsored and -enacted homophobia in order to realize the right to health for sexual and gender minorities, and stress the importance of using a comprehensive, yet carefully context-specific, human rights analysis.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Thabo and Palesa, who shared their stories with me; the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback on the first version of the manuscript; Talia Meer and Sarah Spencer for their feedback on various versions of this article; and the South African Social Science and HIV Programme (SASH), a joint program of the University of Cape Town with Brown University, for the fellowship that supported me during the writing of the manuscript.

Alexandra Muller, MD, Gender Health and Justice Research Unit, University of Cape Town, Cape Town/ South Africa

Please address correspondence to Alexandra Muller. Email: alexandra.muller@uct.ac.za

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2016 Muller. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- N. Pillay, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Discriminatory laws and practices and acts of violence against individuals based on their sexual orientation and gender identity, para. 1, A/HRC/19/41 (2011). Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/docs/19session/a. hrc.19.41_english.pdf.

- R.G. Parker, “Sexual rights: Concepts and action,” Health and Human Rights 2/3 (1997), 31-37. http://doi.org/10.2307/4065151

- S. Corrêa and R. Petchesky, “Reproductive and Sexual Rights: A Feminist Perspective,” in: G. Sen, A. Germain, and L.C. Chen (eds.), Population Policies Reconsidered: Health, Em- powerment and Rights (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994).

- See, for example, S. Corrêa, R. Petchesky, and R. Parker Sexuality, health and human rights (New York: Routledge, 2008).

- S. Brotman, B. Ryan, Y. Jalbert, and B. Rowe, “The impact of coming out on health and health care access,” Journal of Health & Social Policy 15/1 (2002), pp. 1–29. doi:10.1300/J045v15n01.

- T. Lane, T. Mogale, H. Struthers, J. McIntyre, and S.M. Kegeles, “‘They see you as a different thing’: The experiences of men who have sex with men with healthcare workers in South African township communities,” Sexually Transmitted Infections 84/6 (2008), pp. 430–33. doi:10.1136/sti.2008.031567.

- L.C. Rispel, C.A. Metcalf, A. Cloete, V. Reddy and C. Lombard, “HIV Prevalence and Risk Practices among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Two South African Cities,” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 57/1 (2007), pp. 69–76. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e318211b40a.

- See United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Discussion Paper: Transgender Health and Human Rights (New York: UNDP, 2013); and M. Stevens. Transgender Access to Sexual Health Services in South Africa (Cape Town: Gender Dynamix, 2012).

- See, for example, V.A. Rosario, Science and Homosexualities (New York: Routledge, 1997).

- G. Smith, “Treatments of homosexuality in Britain since the 1950s–an oral history: the experience of patients,” BMJ 328 (2004), pp. 427–30.

- T. Wilton Sexualities in Health and Social Care (Berkshire: Open University Press, 2000).

- For a comprehensive overview, see J. Drescher, P. Cohen-Kettenis, and S. Winter, “Minding the Body: Situating Gender Identity Diagnoses in the ICD-11,” International Review of Psychiatry 24/6 (2012), pp. 568–77. doi:10.3109/09540261.2012.741575.

- Summarized in Drescher et al. (see note 12). Also Cape Town Declaration against the diagnosis of ‘gender incongruence in childhood’, available online at http://www.genderdynamix.org.za/%E2%80%8Bcape-town-declaration/

- Juan Méndez, UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, UN Doc. A/HRC/22/53 (2013), para. xxvi–xxix.

- See, for example, C. Logie, “The case for the World Health Organization’s Commission on the Social Determinants of Health to address sexual orientation,” American Journal of Public Health 102/7 (2012), pp. 1243–6. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300599; K.H. Mayer, J.B. Bradford, H.J. Makadon, R. Stall, H. Goldhammer, S. Landers, “Sexual and gender minority health: what we know and what needs to be done,” American Journal of Public Health 98/6 (2008), pp. 989–95. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.127811; and F. Pega & J.F. Veale, “The Case for the World Health Organization’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health to Address Gender Identity,” American Journal of Public Health 105/3 (2015), pp. e58–e62. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302373.

- Mayer et al. (see note 15)

- T. Sandfort, L. Baumann, Z. Matebeni, V. Reddy, and I. Southey-Swartz, “Forced Sexual Experiences as Risk Factor for Self-Reported HIV Infection among Southern African Lesbian and Bisexual Women,” PloS One 8/1 (2013), p. e53552. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053552.

- Logie (see note 15)

- N. Pillay, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (see note 1), para. 5-7.

- M. Schuster, “On Being Gay in Medicine,” Academic Pediatrics 12/2 (2012), pp. 75–78. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2012.01.005; H.J. Makadon, “Improving Health Care for the Lesbian and Gay Communities,” New England Journal of Medicine 354/9 (2006), pp. 895–97; J. Lapinski, P. Sexton, “Still in the closet: the invisible minority in medical education,” BMC Med Educ 14 (2014), pp.171.

- M.H. Townsend, M.M. Wallick, and K.M. Cambre , “Follow-up survey of support services for lesbian, gay, and bisexual medical students,” Acad Med 71/9 (1996), pp. 1012–1014.

- M.J. Eliason, S.L. Dibble, and P.A. Robertson , “Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) physicians’ experiences in the workplace,” J Homosex 58/10 (2011), pp. 1355–1371.

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI), (1966). Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/cescr.htm.

- Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 20, Non-Discrimination in Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (Art. 2 Para. 2), E/C.12/GC/20, Section 32, Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cescr/docs/gc/E.C.12.GC.20.doc.

- Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, UN Doc. No. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000). Available at http://www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/0/40d009901358b0e2c1256915005090be?Opendocument.

- Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. (Pretoria: Government of South Africa, 1996).

- Minister of Health and Others v Treatment Action Campaign and Others (No. 2) (CCT8/02) [2002] ZACC 15; 2002 (5) SA 721; 2002 (10) BCLR 1033 (July 5, 2002), Available at http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZACC/2002/15.html.

- Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) Guidelines for good practice in the health care professions: National Patients’ Rights Charter (Pretoria: HPCSA, 2008); and Department of Health KwaZulu Natal. Batho Pele Principles. (Pretoria: DoH, Not dated), available online at: http://www.kznhealth.gov.za/bathopele.htm.

- Constitution of South Africa (see note 26), Article 7(2).

- Medical Schemes Act No. 131 of 1998; Domestic Violence Act No. 116 of 1998; Refugees Act No. 130 of 1998.

- Civil Union Act No. 17 of 2006.

- A. Carroll and L.P. Itaborahy, State Sponsored Homophobia 2015: A world survey of laws: Criminalisation, protection and recognition of same-sex love (Brussels: ILGA, 2015).

- M. Epprecht, “Sexual minorities, human rights and public health strategies in Africa,” African Affairs 111/443 (2012), pp. 223–243: 226.

- Epprecht (see note 33).

- African Commission on Human and People’s Rights. Resolution 275: Resolution on Protection against Violence and other Human Rights Violations against Persons on the basis of their real or imputed Sexual Orientation or Gender Identity (2014). Adopted at the 55th Ordinary Session of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights in Luanda, Angola, April 28 to May 12, 2014.

- Epprecht (see note 33)

- D.DeLange, “Call to Suspend ANC MP for Opening Fire on Gay Rights,” Cape Times (May 8, 2012).

- P. Fabricius, “SA Fails to Back Efforts at UN to Protect Gays,” Cape Times (June 23, 2010).

- Two manuscripts from the larger study are currently under review. The results have been presented at conferences: Müller, A, “Barriers to health service access for sexual and gender minorities in South Africa” (2014), Oral presentation, 3rd Global Symposium on Health Systems Research, October 2, 2014, Cape Town, South Africa.; and Müller, A., “Access to public health care for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender South Africans” (2014), Oral presentation, Putting Public in Public Services: Research, Action and Equity in the Global South, held April 13-16, 2014, Cape Town, South Africa.

- HPCSA (see note 28).

- J. Cohen and T. Ezer, “human rights in patient care: A theoretical and practical framework,” Health and Human Rights 15/2 (2013), pp. 7–19.

- U. Erel, J. Haritaworn, R. Gutiérrez, and C. Klesse, “On the Depoliticisation of Intersectionality Talk. Conceptualising Multiple Oppressions in Critical Sexuality Studies,” in A. Kuntsman and E. Miyake (eds.), Out of Place. Interrogating Silences in Queerness/Raciality (New York: Raw Nerve Books, 2008), p. 274.

- B.M. Mayosi, J.E. Lawn, A. van Niekerk et al, “Health in South Africa: changes and challenges since 2009,” The Lancet 380 (2012), pp. 2029-2043.

- H. Coovadia, R. Jewkes, P. Barron, D. Sanders, and D. McIntyre, “The health and health system of South Africa: historical roots of current public health challenges,” The Lancet 374 (2009), pp. 817-834.

- D. Nath and S. Mthathi, “We’ll show you you’re a woman”: Violence and discrimination against Black Lesbians and Transgender Men in South Africa. (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2011).

- N. Mkhize, J. Bennett, V. Reddy, and R. Moletsane, The country we want to live in: Hate crimes and homophobia in the lives of black lesbian South Africans (Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2010).

- Lane et al. (see note 7); Rispel et al. (see note 7); R. Smith, “healthcare experiences of lesbian and bisexual women in Cape Town, South Africa,” Culture, Health & Sexuality 17/2 (2015), pp. 180-93. doi:10.1080/13691058.2014.961033.

- A. Müller, S. Röhrs, Y. Hoffman-Wanderer, and K. Moult, ““You have to make a judgment call” – Morals, judgments and the provision of quality sexual and reproductive health services for adolescents in South Africa,” Social Science & Medicine 148 (2016), pp. 71–78. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.048; K. Wood and R. Jewkes, “Blood blockages and scolding nurses: barriers to adolescent contraceptive use in South Africa,” Reproductive Health Matters 14/27 (2006), pp. 109–18. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(06)27231-8.

- Pew Research Center. A global study on societal acceptance of homosexuality. Available at http://www.pewglobal.org/files/2013/06/Pew-Global-Attitudes-Homosexuality-Report-FINAL-JUNE-4-2013.pdf.

- K. Fallin-Bennett, “Implicit bias against sexual minorities in medicine: cycles of professional influence and the role of the hidden curriculum.” Acad Med 90/5 (2015), pp. 549–552.

- M.J. Yesidia, “Changes in physicians’ attitudes toward AIDS during residency training: a longitudinal study of medical school graduates,” J Health Soc Behav 37/2 (1996), pp. 179-191.

- H. Schneider, “Getting to the truth? Researching user views of primary health care,” Health Policy and Planning 17/1 (2002), pp. 32–41. http://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/17.1.32

- A. Müller, “Public health care for South African LGBT people: Health rights violations and accountability mechanisms” (presentation at Putting Public in Public Services: Research, Action and Equity in the Global South, Municipal Services Project conference, Cape Town, South Africa, April 14, 2014).

- Sandfort et al. (see note 17)

- A. Müller, “Teaching Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Health in a South African Health Sciences Faculty: Addressing the Gap,” BMC Medical Education 13 (2013), p. 174. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-13-174.

- L. Kelley, C.L. Chou, S.L. Dibble, and P.A. Robertson, “A critical intervention in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health: knowledge and attitude outcomes among second-year medical students,” Teaching and Learning in Medicine 20/3 (2008), pp. 248–253. http://doi.org/10.1080/10401330802199567; W. White et al., “Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patient care: medical students’ preparedness and comfort,” Teaching and Learning in Medicine 27/3 (2015), pp. 254–263. http://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2015.1044656; and K. Daskilewicz and A. Müller, “These are the topics you cannot run away from” – Teaching lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex health-related topics to medical and nursing students in Malawi and South Africa (UCT: GHJRU, in press).

- J.A. Giles and E.J.R. Hill. “Examining our hidden curricula: powerful, visible, gendered and discriminatory,” Med Educ 49 (2015), pp. 244–246.

- A. Müller and S. Crawford-Browne, “Challenging medical knowledge at the source – attempting critical teaching in the health sciences,” Agenda : Empowering Women for Gender Equity 27/4 (2013), pp. 22-34. http://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2013.855527; and A.H. Mavhandu-Mudzusi and P.T. Sandy, “Religion-related stigma and discrimination experienced by lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender students at a South African rural-based university,” Culture, Health & Sexuality 17/8 (2015), pp. 1049-1056. http://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2015.1015614

- Logie (see note 15); A. Müller, “Strategies to include sexual orientation and gender identity in health professions education.” African Journal for Health Professions Education 7/1 (2015), pp. 4-7.

- Cohen and Ezer (see note 41)

- A. Carroll and L.P. Itaborahy (see note 32).

- N. Pillay, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (see note 1), para. 54-57.

- Anand Grover, UN Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, A/HRC/14/20 (2010) Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/docs/14session/A.HRC.14.20.pdf.

- Yogyakarta Principles, available at: http://www.yogyakartaprinciples.org/.

- A.M. Miller, “Sexual but not reproductive: exploring the junction and disjunction of sexual and reproductive rights,” Health and Human Rights 4/2 (2000), pp. 68-109. http://doi.org/10.2307/4065197

- B. Klugman, “Sexual rights in Southern Africa: A Beijing discourse or a strategic necessity?” Health and Human Rights 4/2(2000), pp. 144-173. http://doi.org/10.2307/4065199

- Epprecht (see note 33) and Miller (see note 65).