Violeta Zopunyan, Suren Krmoya, Ryan Quinn

Health and Human Rights 15/2

Published December 2013

Abstract

Background: Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Republic of Armenia has undergone an extensive legislative overhaul. Although a number of developments have aimed to improve the quality and accessibility of Armenia’s health care system, a host of factors has prevented the country from fully introducing measures to ensure respect for human rights in patient care. In particular, inadequate health care financing continues to oblige patients to make both formal and informal payments to obtain basic medical care and services. More generally, a lack of oversight and monitoring mechanisms has obstructed the implementation of Armenia’s commitments to human rights in several international agreements.

Methods/Objectives: Within the framework of a broader project on promoting human rights in patient care, research was carried out to examine Armenia’s health care legislation with the aim of identifying gaps in comparison with international and regional standards. This research was designed using the 14 rights enshrined in the European Charter on Patient Rights as guiding principles, along with domestic legal acts relevant to the rights of health care providers.

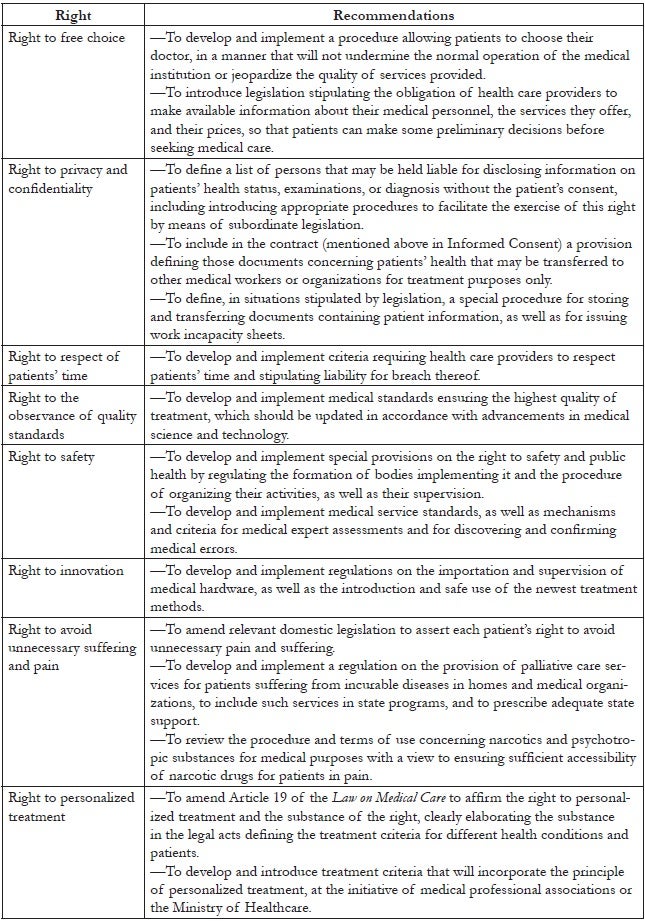

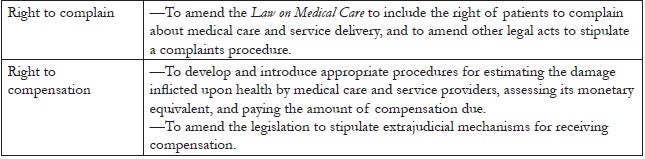

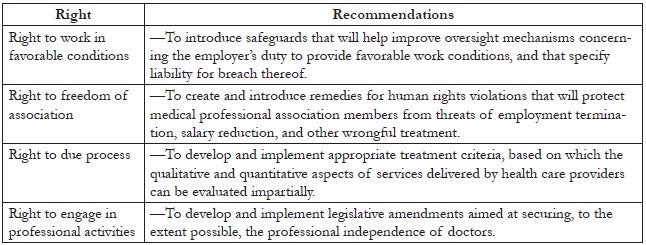

Findings: The gaps analysis revealed numerous problems with Armenian legislation governing the relationships between stakeholders in health care service delivery. It also identified several practical inconsistencies with the international legal instruments ratified by the Armenian government. These legislative shortcomings are illustrated by highlighting key health-related rights violations experienced by patients and their health care providers, and by indicating opportunities for improved rights protections. A full list of human rights relevant to patient care and recommendations for promoting them in the Armenian context is provided in Tables 1 and 2.

Discussion: A number of initiatives must be undertaken in order to promote the full spectrum of human rights in patient care in Armenia. This section highlights certain recommendations flowing from the findings of the gap analysis, including further work needed to make pain relief medication more accessible to patients with chronic or terminal illness. New initiatives are also suggested, such as the establishment of an independent body of medical professionals and ethicists mandated to resolve disputes between patients and providers, and other efforts intended to ensure that the rights of patients and providers alike are upheld and respected.

Introduction and background

Situated in the South Caucasus region, the Republic of Armenia declared its independence from the Soviet Union in 1990. Its independence was officially recognized upon the dissolution of the USSR, and the Armenian Constitution came into force in 1995. However, Armenia’s initial post-Soviet years were hampered by economic difficulty and political instability. Full-scale armed conflict between the Karabakh Armenians and neighboring Azerbaijan resulted in the blockage of Armenia’s borders with Turkey and Azerbaijan, compounding deeply rooted economic and demographic problems. Presently, Armenia’s population is estimated at 2,974,184.1 The country’s international relations are generally positive, with the lingering exceptions of Turkey and Azerbaijan. Its relations with countries across Europe, the Middle East, and the Commonwealth of Independent States (the regional organization of many states that were formerly part of the Soviet Union) in particular have offered fruitful opportunities for increased trade and development.

As a post-Soviet state, Armenia inherited a centralized health care system guaranteeing free medical care and access to a comprehensive range of primary, secondary, and tertiary health care services for the entire population. This universal coverage was intended to serve the policy goal of protecting and improving the health of the population irrespective of nationality, ethnic background, and religion.2 Armenia’s health care system initially stayed under centralized state control, its medical services funded by general government revenues. National social and economic development plans tended to prioritize increasing numbers of doctors and hospital beds and related investments in hospital development over concrete health care outcomes. Primary health care in Armenia has been particularly marked by technological shortcomings, as much greater emphasis has been placed on specialized health care in the country.

Recent years have seen Armenia’s health care system undergo several changes deeply affecting all stakeholders in health care delivery. Perhaps most notably, the decentralization of public services catalyzed the transfer of control over health care to local and provincial governments. While the Armenian government continues to suggest reforms emphasizing improved state budget financing and more efficient use of resources, the majority of financing for public health care institutions continues to come from payments both formal (such as fees for medical services set by law and paid to the hospital) and informal (such as out-of-pocket payments made as “gratuities” to doctors).3 Moreover, a number of Armenian medical institutions have become privatized in response to the lack of centralized funding, forcing them to compete with other private and state facilities in charging for their health care services. As a result, full access to quality health care remains out of reach for much of the Armenian population, not least its socially marginalized groups, such as people with mental disabilities, people living with HIV/AIDS, and palliative care patients. In sum, health care regulation in Armenia remains in a stage of transition.

Armenia’s newfound independence has required it to undergo a legislative overhaul, as the Soviet legislation formerly governing it does not serve an independent country. Legislative reform has proven a major challenge for Armenia, and in many cases, its legislative developments have failed to align with internationally respected health and human rights standards. In recent years, however, Armenia has adopted a series of substantive reforms intended to harmonize its legal regime with European and international standards, including key agreements relevant to human rights in patient care. These include the following:

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), adopted in 1993;

- European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), adopted in 2002; and

- European Social Charter (ESC), adopted in 1996, and entered into force in 2004.4

Significantly, international treaties ratified by Armenia’s National Assembly are considered the supreme law of the country, meaning that their provisions prevail over all domestic legislation.5 However, implementation of these instruments remains problematic; absent effective oversight and monitoring mechanisms, the instruments remain largely aspirational. Armenia has yet to exhibit full and meaningful judicial independence, and its short history as an independent country has not yielded an extensive body of constitutional or international jurisprudence.

There is thus a strong need to measure the gaps between Armenia’s international human rights commitments and its domestic legislation in order to determine how its health care system can change its culture to embody respect for human rights in patient care. This is particularly important in view of the opportunity presented by the current draft Law on Healthcare, whose protection of human rights in patient care can benefit from thorough scrutiny of the country’s Law on Medical Care and Services of the Population (henceforth, Law on Medical Care), its criminal code, and its constitution. Without concerted commitment from the Armenian government, this work has primarily fallen to civil society organizations committed to advocating for patients’ and health care providers’ rights and raising awareness about human rights violations among state and international bodies.

Methods

As Gerovski and Alcheva discuss in their paper featured in this same issue, the research for Armenia and other countries studied was developed through the collaboration of a multidisciplinary working group comprising international experts, national public health workers, lawyers, civil society organizations, and representatives from government bodies.6 Its aim was to identify gaps in legislation and practice related to human rights in patient care, with particular attention devoted to national and international mechanisms for rights protection, as well as particular challenges arising in the relationships between government, health care providers, and patients.

Using the European Charter of Patient Rights as a guiding document, the working group analyzed the domestic legal canons of Armenia and other transitioning countries in order to comprehensively identify shortcomings in health care delivery, in addition to opportunities for realizing a full spectrum of human rights in patient care.7 In contrast with a focus on “patients’ rights,” the conceptual approach to “human rights in patient care” considers the relevance of human rights principles to all stakeholders in health care, including physicians, nurses, sanitation inspectors, health care support staff, public health workers, and patients.8

Findings

The gaps analysis carried out by the working group resulted in the identification of significant gaps in Armenian health care legislation and, in particular, several cases of noncompliance with the country’s regional and international agreements. The rights outlined below are but a few of the rights pertinent to patient care that are routinely violated in Armenian health care delivery.

Right to access medical services

The right to access medical services is central to the right to the highest attainable standard of health, as set out in ICESCR Article 12 and ESC Article 11, as well as the right to life assured by ECHR Article 2(1). Furthermore, medical services must be provided without discrimination in accordance with Article 2(2) of the ICESCR. Current Armenian legislation sets out numerous provisions aimed at fulfilling patients’ right to access medical care without discrimination and without regard for financial or geographic constraints. Armenia’s constitution guarantees everyone the right to receive medical care and services in the manner prescribed by law, as well as the right to free of charge basic medical services.9 With greater specificity, the Law on Medical Care—the main domestic legal act regulating Armenian health care—sets out the right to receive medical care and services irrespective of nationality, race, sex, language, religion, age, health status, political or other views, social origin, property ownership, or other status.10

The Law on Medical Care also distinguishes two main types of medical services: (1) primary medical care, guaranteed free of charge and requiring only basic health care methods and technologies; and (2) specialized medical care, defined by the special diagnostic methods and sophisticated medical technologies it requires. In accordance with this distinction, the Armenian government has enacted separate legal acts governing health care for a number of socially marginalized groups, including people who use drugs, people living with HIV/AIDS, people with mental disabilities, detainees, and palliative care patients.11 A government decree in 2004 further specifies which medical services are guaranteed by the state and sets out the conditions under which citizens are entitled to them.12 There remains, however, no effective means of ensuring that the right to access medical services is upheld, and many patients can only gain access to adequate medical treatment by making out-of-pocket payments to their health care providers.

The prices set by the Armenian government for medical services are prohibitively high for low-income patients. For this reason, in 2011 the Armenian Ministry of Healthcare introduced a co-payment system with the dual aim of ensuring adequate compensation for medical care and services while promoting the affordability of health care costs for the Armenian population.13 Co-payment involves a payment made by patients equal to the difference between the treatment cost defined in the framework of state-guaranteed medical care and the real cost incurred by a health care facility for services provided (as confirmed by the Ministry of Healthcare). However, a number of infringements of this co-payment regime have been reported among patients who are members of socially marginalized groups.14 As well, in many cases, persons with disabilities have been denied access to free medical care even though they are enumerated in the 2004 decree; also, diabetes patients have been obliged to pay for drugs that are guaranteed free of charge.15 The economic burden of such health problems is devastating to endure; reasonable government investment in health care services could easily contribute to better living conditions for all Armenians. Violating the financial component of the right to access medical services is both a cause and a consequence of poverty, and certainly it results from inadequate state budget allocations.

The geographic component of the right to access medical services is also fraught with complications, as health care services are of much poorer quality in Armenian rural settings than in its cities. Despite a series of initiatives intended to improve the quality and availability of medical treatment in rural areas, many patients aim to move to Yerevan, the Armenian capital, or other cities promising better-quality health care. Common arguments for this trend are that doctors in rural areas are less qualified than their urban counterparts, that rural medical institutions—even when renovated—are poorly equipped and lacking in medical specialists, and that villagers lack appropriate transportation needed to reach the nearest ambulatory or specialized hospitals. For these reasons, as well as a trend in health care providers moving to urban centers to practice in superior health care facilities, the right to access medical services remains seriously undermined in Armenia’s rural regions.

Lastly, the right to access medical services is violated routinely through discrimination based on health status or on patients’ experience with Armenia’s criminal justice system. Pervasive stigma against people living with HIV/AIDS—who total approximately 3,500 in Armenia—results in their being denied medical treatment even in the specialized hospitals they require for ongoing treatment.16 Armenian prisoners and detainees, for their part, must endure highly unsanitary conditions while in custody. They are routinely denied adequate contact with physicians, as well as preventive care and treatment for serious medical conditions, particularly those requiring specialized medical expertise.17 Overall, while many layers of domestic legislation guarantee all Armenians the right to access medical services, large segments of the population still face serious financial, geographic, and discriminatory barriers.

Right to confidentiality

One of the most important patients’ rights is the right to privacy and confidentiality, which Armenia is bound to respect under ECHR Article 8(1). Armenia has taken steps to respect this obligation, notably under Article 5 of the Law on Medical Care, which assures all patients the right to confidentiality regarding the very fact they consulted with a physician as well as the state of their health and any information gathered during examinations, diagnostics, and treatment.18 Article 19(c) of the same statute sets out a reciprocal provision concerning the obligations of medical care and service providers to respect their patients’ confidentiality, except in cases provided for by Armenian legislation.19 An example of such an exception is when disclosure is required by law enforcement agencies. Troublingly, these last are not under a duty not to publish this information, and patient information is often disseminated through various mass media outlets, which are likewise under no special obligation to assure the confidentiality of medical records.20

To be sure, Article 145 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Armenia proscribes the disclosure of information about a patient’s illness or medical test results by medical personnel without any professional or official need.21 This signals that information deemed medically confidential may be disclosed only upon the request of the courts, the prosecutor’s office, authorities carrying out investigations, and other authorized entities in situations and according to procedures set by law. (Of course, no criminal liability attaches to the disclosure of such information with the patient’s consent.) Despite the punishment prescribed by the criminal code for unauthorized disclosure of patient information, the right to confidentiality is commonly violated, particularly in regards to information about people living with HIV/AIDS, people living with cancer, and people with mental disabilities. These patients are often reluctant to file lawsuits for breaches of their right to confidentiality out of fear that even more people will learn of their health status, which is often highly stigmatized in Armenian society. This is so despite legislative provisions promoting the principle of respect for a person’s rights, freedoms, and human dignity throughout court proceedings and limiting public access to court hearings under certain circumstances.22

The main gaps precluding robust protection of the right to confidentiality include the lack of comprehensive regulations regarding the circulation of different kinds of patient information, as well as the lack of an authoritative definition of “medical secret” for Armenian health care providers. If these gaps were filled, it would prove easier to identify and report violations of the right to confidentiality and to develop legal norms for deciding fault in disputes involving the wrongful disclosure of patient information.

Right to complainThe right to complain about improperly delivered medical services is critical to the meaningful realization of the right to remedies for human rights violations, as set out in ECHR Article 13. Armenia’s constitution broadly stipulates that everyone is entitled to protect their rights and freedoms by any means not prohibited by law, and it also guarantees the right to effective legal remedies for rights violations as determined by judicial or other public bodies.23 The constitution further provides citizens with the option to enlist the Human Rights Defender in support of the protection of their rights and freedoms, as well as the option to apply for this protection from international institutions to which Armenia is linked.24 (The Human Rights Defender in Armenia is mandated to respond to individual complaints of human rights violations committed by state bodies.) In cases of improperly delivered medical services, however, the most effective way to protect or vindicate one’s rights is by means of judicial procedure, including administrative, civil, and criminal procedure.25 However, judicial determinations of medical malpractice and of the quality of medical services delivered are possible only when medical forensic experts can attest to them.

Due to an overloaded court system as well as widespread wariness about the impartiality of judges and medical experts alike, many patients and health care personnel whose rights have been violated avoid pressing charges. In many such cases, their only recourse is that of civil society organizations actively working on human rights protection in Armenia. There is thus an urgent need in the country to improve extrajudicial procedures that save time and expense in providing redress for violations of patients’ and providers’ rights. These may include the selection of independent health ombudspersons who can address patient complaints, as well as impartial trade unions that can address provider complaints, particularly about unsuitable working conditions. The timely and consistent approach to complaints that such institutions can provide are ideal for resolving disputes as well as for enhancing the public profile of civil society members committed to advancing health and human rights in Armenia.

A significant gap preventing patients from exercising the right to complain is the lack of a precise definition of those to whom health-related rights violations should be reported. Article 19 of the Law on Medical Care states that “medical service implementers” bear responsibility for dealing with illegal or improper medical activities, particularly where fault has caused damage to human health.26 The term “medical service implementers” is unduly vague, leaving patients perpetually uncertain about how and where to file a complaint about improper medical service delivery. Moreover, when the term is understood to refer to doctors, nurses, medical support staff, or a given medical institution as a whole, it is problematic to direct patients to file their complaints with parties that are all, to varying extents, involved in providing the very medical services of which a patient might complain. The Armenian government should take steps to clarify or change the term “medical service implementers” so that patients and health care providers alike might better exercise their right to complain in a health care context.

Right to observance of quality standardsThe right to the observance of quality standards in health care is closely related to the right to the highest attainable standard of health, as assured by ICESCR Article 12 and ESC Article 11, as well as the right to life reflected in ECHR Article 2(1). Armenia’s legislated standards for the provision of quality medical services are imperfect. The government issues licenses to health care providers under procedures established by Armenian legislation, and compliance with the terms and conditions of such licensing is required in order to provide medical care and services.27 Notably, medical professionals educated in other countries may deliver health care services in Armenia in accordance with the various international agreements ratified by the country.28 With the aim of ensuring the quality of medical care and services provided, the state requires health care providers to meet certain quantitative and qualitative standards in their service provision.29

As a result of the distinction in Armenian legislation between primary and specialized health care, two types of quality standards for health care provision exist in the country. The first type concerns standards for the organization of medical services in hospitals. These include the definition of activities required of medical personnel as well as specific provisions governing documentation, patient registration, necessary equipment, and other administrative issues and special instructions pertinent to specific fields of medicine. The second type of quality standards covers clinical guidelines relevant to treatment methods, prescriptions, and other interventions required for specific symptoms and illnesses, in keeping with current scientific expertise. The Armenian Minister of Healthcare has recently adopted several standards of the first type, mainly concerning those medical services that the state guarantees free of charge.30

One gap precluding enjoyment of the right to observance of quality standards in Armenian health care is the inadequacy of the second type of quality standards. Clinical guidelines or standard procedures are often underdeveloped, making it difficult when it comes to assigning responsibility in disputes between patients and health care providers. In cases of alleged medical malpractice, the law requires that an expert committee provide its forensic expertise to assist in the determination of fault. However, this committee may be composed of those in the medical field who have yet to yield to innovative treatment methods accepted by the medical science community at large, and their conclusions may be strongly biased given that they work in a small country where most medical experts are familiar with one another. When such forensic experts are corrupt, physicians may be accused and even convicted of a medical error or other fault that may not even have occurred, rendering them vulnerable whenever patients complain of inappropriate care and demand financial compensation. This vulnerability is compounded by the fact that such medical errors can range from the provision of inappropriate care to the improper execution of appropriate care.

The risk of wrongful conviction is notable given that Armenian courts are still undergoing reforms aimed at improving the impartiality, independence, and efficiency of judicial power.31 Without appropriate safeguards securely in place, the conclusions reached by forensic experts and judges alike remain susceptible to improper influence. It is crucial that the Armenian government take steps to adopt clear and comprehensive medical criteria to ensure that its health care providers can feel confident in delivering high-quality treatment in line with current developments in medical science and technology. This is particularly urgent given that Armenian legislation requires that criminal charges be filed against medical institutions or physicians in cases of medical malpractice.32

Right to avoid unnecessary suffering and pain

In recognition of the right to avoid unnecessary suffering and pain, Article 12 of the ICESCR obliges its signatories to take measures to facilitate access to palliative care and pain treatment. In fact, the former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture has stated that “the de facto denial of access to pain relief, if it causes pain and suffering, constitutes cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment,” thus implicating Armenia’s obligations under ECHR Article 3, given the current palliative care situation in Armenia.33 At present, there exist a number of gaps preventing patients with long-term illnesses in Armenia from exercising their right to adequate pain relief. Effective analgesics and other pain relief medications do not reach these patients for a variety of reasons, including inadequate domestic legislation, a lack of oral opioids, a shortage of properly trained palliative care specialists, and low levels of awareness about pain relief possibilities among patients and their relatives.34 These problems are compounded by widespread and exaggerated fears of addiction, particularly among law enforcement agencies and other state actors, who favor a highly restrictive approach to pain relief medication. The nationwide need for palliative care in Armenia is estimated to total approximately 3,000 patients per day and 18,000 patients per year.35 Until recently, no legislative provision concerning palliative care and pain relief existed in Armenia; only in 2009 was “palliative care” added to the list of medical services provided in Armenia.36 In 2012, the Armenian government endorsed the “Palliative Care Concept Paper,” which describes current legal and practical problems affecting the right to avoid unnecessary suffering and pain and identifies regulatory strategies for promoting respect for this right and bringing current practices in line with international standards on pain relief.37

Despite these recent legislative developments, chronically and terminally ill patients in Armenia continue to be denied effective pain relief, as documented by a series of recent cases involving violations of the right to avoid unnecessary suffering and pain.38 Current domestic legislation allows physicians to prescribe narcotic drugs for pain relief, but a lack of specific procedural regulations for their medical use persists.39 Moreover, a number of domestic legislative provisions affecting pain relief in Armenia are mutually inconsistent. Article 22(6) of the Law on Narcotics and Psychotropic Substances, for instance, prohibits pharmaceutical professionals from issuing pain relief drugs on the basis of a prescription older than 10 days, while a later government decree stipulates that such prescriptions are valid for 20 days.40 These discrepancies complicate the efforts of patients and their relatives to obtain timely and effective pain relief. Often, such efforts are already burdensome as a result of the suffering and pain occasioned by chronic illness. Both the Armenian government and the country’s civil society organizations must work to guarantee fulfillment of the right to avoid unnecessary suffering and pain. This must be done not only by harmonizing domestic legislation governing access to pain relief with international standards, but by raising awareness among health care providers, law enforcement and other state actors, and patients and their relatives about the need for enhanced access to analgesics and other pain relief medications.

Rights of health care providers

As mentioned earlier in this analysis, the rights of health care providers are a key component of the human rights in patient care framework. Most prevalent and alarming among violations of medical professionals’ rights are those concerning the right to work in decent conditions and the right to receive fair wages and equal remuneration. Other rights applicable to health care providers and set out in Armenian legislation include the right to form and join professional associations, as well as targeted medical licensing activities within the framework of such associations; the right to participate in public health insurance programs; the right to protect one’s honor, dignity, and professional reputation; and the right to insure one’s professional activities.41 Medical professionals are also assured the rights set out in the Labor Code of Armenia, among other rights set out in Armenian legislation.42

However, many health care providers in Armenia decline to initiate complaint procedures that might vindicate their rights because of their low levels of awareness about the legal remedies available, as well as their fears about retaliation from colleagues within a hierarchical hospital system. Indeed, a series of complex bureaucratic requirements not only inhibits Armenian health care providers from claiming their rights to work in favorable conditions but prevents them from providing quality medical care to their patients. One result of the lack of effective protection and enforcement of providers’ rights in Armenia is that many experienced medical professionals opt to leave the country and practice elsewhere, frustrated by their low salaries and substandard work conditions (particularly in rural regions of Armenia) as well as by the state’s failure to defend them in disputes with patients. Armenia’s health care system as a whole would benefit from more thorough protection of medical care and service providers’ rights, including a rigorous system for receiving and resolving their complaints.

Discussion

The findings above signal important deficiencies in Armenian legislation with respect to the rights of patients and health care providers. Table 1 shows the recommendations developed in accordance with the patients’ rights stipulated in the European Charter of Patient Rights.43 Crucial opportunities for improving the country’s health care system include infusing the current draft Law on Healthcare with effective protections that reflect the full spectrum of human rights in patient care and that bring Armenian legislation in line with the international legal instruments ratified by the Armenian government. More specifically, critical definitions such as “patient,” “palliative care,” and “medical service implementers” require refinement, and the country’s mechanisms for financing health care call for improvements that assure the accessibility and delivery of quality health care to all Armenians.

A number of significant developments affecting health care service delivery in Armenia are already underway. These include a working group convened by the Ministry of Healthcare and consisting of lawyers, representatives of nongovernmental organizations, and physicians working in pilot sites. (In 2012, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria funded four pilot palliative care service sites in Armenia—two in Yerevan and two in rural regions.) The mandate of this working group has been to gradually implement the amended Law on Narcotics and Psychotropic Substances, which provides enhanced protections for prescribing narcotic pain relief drugs to patients with acute and chronic pain conditions.44 This legislative development lends considerable support to the right to avoid unnecessary suffering and pain and is intended to bring Armenia’s policies and practices concerning pain relief in line with the international legal instruments it has ratified. These include the United Nations’ 1972 Protocol Amending the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs 1961 and its Convention on Psychotropic Substances (1971), the latter of which requires states to safeguard access to psychotropic substances for medical and scientific purposes and recognizes that such substances are often inaccessible to persons in need.45 More legal and policy reform is needed, however, in order to realize more fully the right to pain relief in Armenia. In particular, bureaucratic barriers to timely and effective drug prescriptions must be removed, police scrutiny of opioid prescriptions must be lessened, and efforts to raise awareness among the general public about the importance of palliative care must be undertaken and supported by the Armenian government.

The right to access medical care and services in Armenia must be reaffirmed as applying to all members of the population without discrimination. In order to achieve full realization of this right, however, the rights of medical providers must also be comprehensively advanced, given their central role in providing this access. This would be greatly assisted by establishing an independent body of medical professionals and ethicists for the resolution of disputes between patients and health care providers, as well as by introducing more comprehensive clinical standards setting out the obligations of medical professionals in respect of specific medical conditions and procedures. Table 2 shows the recommendations for action on the rights of medical providers, as determined by the working group.

Armenia’s health care system would also benefit from more detailed standards for legal professionals regarding procedures for health-related evidence collection, in part to encourage attorneys to take on cases of human rights violations in health care contexts and to promote the development of health-related jurisprudence. For these rights and others explored in the preceding section, the international and regional agreements ratified by the Armenian government can serve as helpful guides in understanding and promoting the full spectrum of human rights in patient care, as well as in affirming their interrelatedness.

Conclusion

This initiative on promoting human rights in patient care was made possible by research from Armenian civil society organizations focusing on protecting patients’ and health care providers’ rights, as well as their work raising health-related rights awareness among socially marginalized groups and supporting individuals in claiming and defending their rights. These NGOs include the Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly (Vanadzor Office); Real World, Real People; Public Information and Need of Knowledge; and the Women’s Resource Center. Their beneficiaries include people living with HIV/AIDS, LGBT communities, palliative care patients, people with mental disabilities, and prisoners and detainees. More focused commitment to these issues on the part of the Armenian government would help secure nationwide respect for human rights in patient care and allow the country to fulfill the many international agreements it has ratified. As explored above, significant discrepancies remain between different pieces of Armenian legislation, and between these last and the international human rights instruments ratified by the Armenian government. These gaps preclude the recognition and enforcement of the right to access medical services, the right to confidentiality, the right to complain, the right to observance of quality standards, and the right to avoid unnecessary suffering and pain, in addition to rights specific to health care providers.

The findings and recommendations flowing from this research have been submitted to Armenia’s Ministry of Healthcare as well as to the Standing Committee on Health Care, Maternity and Childhood of Armenia’s National Assembly. Moreover, the majority of its suggestions have already been reflected in the draft Law on Healthcare. Both the Armenian government and the country’s civil society organizations must continue to work to ensure that the rights of patients and health care providers alike are made meaningful at every stage of health care delivery.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this analysis was provided by the Open Society Foundations.

Table 1. Recommendations regarding patients’ rights and health care providers’ responsibilities

Table 2. Recommendations regarding rights of medical care and service providers

Violeta Zopunyan, LLB, is the Legal Supervisor for the Human Rights in Patient Care Program at the Center for Rights Development in Yerevan, Republic of Armenia.

Suren Krmoyan, DL, is a Lawyer and Head of Staff in the Ministry of Healthcare, Yerevan, Republic of Armenia.

Ryan Quinn, MA, is a BCL/LLB Candidate in the Faculty of Law at McGill University, Montréal, Canada.

Please address correspondence to the authors c/o Violeta Zopunyan, Center for Rights Development, 2 Arshakunyats Street, Suite 433, Yerevan, Republic of Armenia, 0023, email: violetazopunyan@gmail.com.

References

1. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), “The world factbook: Armenia” (July 2013). Available at https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/am.html.

2. T. Hakobyan, M. Nazaretyan, T. Makarova, et al., “Armenia: Health system review,” Health Systems in Transition 8/6 (2006), pp. 1–180. Available at http://www.euro.who.int/en/where-we-work/member-states/armenia/publications/armenia-hit-2006.

3. CIA (see note 1).

4. V. Bournazian, A. Harutyunyan, S. Krmoyan, et al., Human rights in patient care: A practitioner’s guide—Armenia (Open Society Foundations, 2009), pp. 12–13. Available at http://www.healthrights.am/docs/pg_eng.pdf; International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI) (1966). Available at http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx; European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), 4 (XI) (1950). Available at http://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Convention_ENG.pdf; European Social Charter (ESC), STE No. 163 (1996). Available at http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/monitoring/socialcharter/Presentation/ESCRBooklet/English.pdf.

5. Constitution of the Republic of Armenia (1995, amended by referendum in 2005), Art. 6. Available at http://www.parliament.am/legislation.php?sel=show&ID=1&lang=eng [unofficial government translation].

6. F. Gerovski and G. Alcheva, “Implementation of patients’ rights legislation in the Republic of Macedonia: Gaps and disparities,” Health and Human Rights: An International Journal 15/2 (2013) (see elsewhere in this issue); see also L. Beletsky, T. Ezer, J. Overall, et al., Advancing human rights in patient care: The law in seven transitional countries (Open Society Foundations, 2013). Available at http://opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/Advancing-Human-Rights-in-Patient-Care-20130516.pdf.

7. Active Citizenship Network, “European Charter of Patients’ Rights” (Rome: Active Citizenship Network, November 2002). Available at http://www.eesc.europa.eu/self-and-coregulation/documents/codes/private/085-private-act.pdf.

8. J. Cohen and T. Ezer, “Human rights in patient care: A theoretical and practical framework,” Health and Human Rights: An International Journal 15/2 (2013) (see elsewhere in this issue).

9. Constitution of the Republic of Armenia (see note 5), Art. 38.

10. Law on Medical Care and Services of the Population (1996), Art. 4 [in Armenian].

11. See the Law on Ensuring Sanitary-Epidemiological Security of the Population of the Republic of Armenia (1992); Law on Prevention of Disease Caused by HIV (1997); Law on Drugs (1998); Law on Narcotics and Psychotropic Substances (2002); Law on Reproductive Health and Reproductive Rights (2002); Law on Transplantation of Human Organs and/or Tissues (2002); Law on Psychiatric Care (2004); Law on Donation of Human Blood and Blood Components (2011).

12. The Republic of Armenia, On Free Medical Care and Services Guaranteed by the State, Government Decree N 318-N (March 4, 2004), Annex N-1, “List of socially vulnerable and specific groups of the population entitled for the state-guaranteed free medical care and services.” Available at http://www.healthrights.am/practitioner-guide/more/1156/#appendix3.

13. The Republic of Armenia, Making Amendments and Additions to the Government Decree N 318-N, dated March 4, 2004, Government Decree N 163-N (February 24, 2011).

14. Economic Development and Research Center and Oxfam (Armenian branch), “Budget financing and copayment system: Public policy assessment in healthcare system,” Policy Discussion Paper (May 2013), pp. 8–10. Available at http://mchealth.am/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Policy-Paper_Eng.pdf.

15. Karen Andreasyan, Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Armenia, Annual report 2012: On the activities of the RA Human Rights Defender and on the violations of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the country during 2012 (Yerevan, Armenia: Office of the Human Rights Defender, 2013), pp. 104–108. Available at http://www.ombuds.am/en.

16. National Center for AIDS Prevention, Ministry of Health of the Republic of Armenia, “Statistics: HIV/AIDS epidemic in the Republic of Armenia.” Available at http://armaids.am/main/free_code.php?lng=1&parent=3.

17. Ashot Harutyunyan v. Armenia (2010), Application No. 34334/04, Eur. Ct. H.R. (Inadequate medical care in detention facility—Art. 3/violation/). Available at http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/sites/eng/pages/search.aspx?i=001-99403.

18. Law on Medical Care (see note 10), Art. 5.

19. Ibid., Art. 19(c).

20. A. Grigoryan, Research on implementation of the right to confidentiality (2013), on file with Center for Rights Development [in Armenian].

21. Criminal Code of the Republic of Armenia (2003), Art. 145.

22. Republic of Armenia Judicial Code (2007), Art. 20; Criminal Procedure Code of the Republic of Armenia (1998, amended 2010), Arts. 16, 170, and 201.

23. Constitution of the Republic of Armenia (see note 5), Art. 18.

24. Ibid.

25. V. Bournazian et al. (see note 4), Chapter 8.

26. Law on Medical Care (see note 10), Art. 19 [from the Armenian, authors’ translation].

27. Ibid., Art. 18.

28. Ibid.

29. Ibid., Art. 19.

30. See Armenian Minister of Healthcare, “Confirming the standards for filing the patient registration slip to rehabilitation hospitals acting within the framework of state order services,” Order N578-A (March 24, 2012); “Approving the standards on HIV/AIDS treatment within the scope of state-guaranteed free health care services for the population,” Order N88-A (January 23, 2012); “Approving the standards on emergency care services of the RA population within the framework of state-guaranteed free health care services,” Order N120 (January 26, 2012); “Confirming the standards on blood collection and related services, blood transfusion therapy within the framework of state order services,” Order N31-A (January 17, 2012); “Approving the standards on state-guaranteed obstetrics and gynecology services,” Order N103-A (January 24, 2012). Available at http://www.moh.am [in Armenian].

31. L. Beletsky et al. (see note 6), p. 38.

32. Criminal Code (see note 21), Art. 130.

33. Manfred Nowak, UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Promotion and Protection of All Human Rights, Civil, Political, Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, including the Right to Development, A/HRC/10/44 (January 14, 2009), para. 72. Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/docs/10session/A.HRC.10.44AEV.pdf.

34. S. R. Connor and H. Karapetyan, Palliative care needs assessment for Armenia (Open Society Foundations, 2010). Available at http://www.stopthepain.am/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/PC-Needs-Assessment-Armenia-Final-Draft1.pdf.

35. Ibid.

36. See Clause 59 of “Government Decree on confirming the list of health care and medical services,” No. 276-N (March 3, 2008).

37. See Republic of Armenia Government Session No. 32 (August 9, 2012) [in Armenian]. Available at http://www.arlis.am/DocumentView.aspx?DocID=77569.

38. Open Society Foundations, Life without pain. Available at http://www.stopthepain.am/en/category/real-life-stories/.

39. Law on Narcotics and Psychotropic Substances (see note 11), Art. 11.

40. Government Decree 759, dated August 14, 2001 (“On Approving the Prescription Form Applied in the Republic of Armenia”); Minister of Healthcare Decree 100, dated February 26, 2002 (“On Approving the Procedure of Issuing Prescriptions and Releasing Drugs”).

41. Law on Medical Care (see note 10), Art. 18.

42. V. Bournazian et al. (see note 4), Chapter 7.

43. Active Citizenship Network (see note 7).

44. Law on Narcotics and Psychotropic Substances (2002), Appendix, “Procedure and Conditions of the Use of Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances for Medical Purposes.”

45. United Nations General Assembly, 1972 Protocol Amending the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs 1961, G.A. Res. 3444 (1972); United Nations General Assembly, Convention on Psychotropic Substances, G.A. Res. 3443 (1971).