Tamar Ezer and Judy Overall

Health and Human Rights 15/2

Published December 2013

Abstract

Background: In Eastern Europe and Central Asia, for society’s most marginalized people, health systems are too often places of violations of basic rights, rather than of treatment and care. At the same time, health practitioners are largely unaware of how to incorporate human rights norms in their work. Additionally, they may face abuses themselves, such as unsafe working conditions and sanctions for providing evidence-based care. Similarly, legal professionals have limited experience working in the health sector, trying to address abuses that occur.

Context: Republics of the former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia have emerged from communism and experienced continued restructuring of their health care systems. As faculties of law, public health, and medicine have sought to incorporate these rapid changes into their curricula, this period of reform and openness to new approaches presented a particular opportunity to integrate human rights education.

Results: The Open Society Foundations have attempted to respond to the need to build health and human rights capacity by supporting the development of over 25 courses in human rights in patient care in nine countries. Targeted at different audiences, these courses are now part of the regular offerings at the academic institutions where they are taught. Student evaluations point to the strength of the interdisciplinary approach and the need to integrate practical examples and exercises. Faculty response has led to the development of a virtual community of practice and series of workshops to gain exposure to new ideas, strengthen interactive teaching, and share materials and experiences.

Reflections: Critical to this initiative has been working with faculty champions in each university, who shaped this initiative to meet the needs in their context. It quickly became apparent that teaching methodology is as important as content in human rights education. Meaningful engagement with health practitioners has entailed connections to day-to-day practice, participatory methodology, inclusion of marginalized voices, and linkages to provider rights and challenges.

Introduction

In Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA), as in many other parts of the world, for society’s most marginalized—people with disabilities, people living with HIV, people who use drugs, and ethnic and sexual minorities—health systems can too often be places of punishment, coercion, and violations of basic rights to privacy and confidentiality, rather than places of treatment and care.1 At the same time, doctors and other health practitioners are largely unaware of how to incorporate ethical and human rights norms in their work. Additionally, they may face abuses themselves, such as unsafe working conditions, lack of due process when complaints are filed against them, and sanctions for providing evidence-based care.2 Legal professionals have not offered much help in such situations, as they have limited experience working in the health sector and addressing the abuses that occur. This paper shares findings and reflections from an Open Society Foundations (OSF) initiative seeking to address this gap through higher education courses providing basic human rights training to the next generation of health practitioners and equipping legal professionals to work at the intersection of law and health in nine EECA countries.

Both authors helped guide OSF’s initiative from its inception, and this paper draws on our personal experiences. While this initiative by no means presents a perfect model and work is still in progress, it provides insights into health and human rights education in EECA, including strengths and gaps. It also offers guidance for the teaching of human rights in patient care more broadly. The first section outlines the context in EECA countries, the second section presents the various components of the OSF initiative, and the final section shares reflections and lessons from this work, indicating areas for further development.

Context

The participating countries in the initiative were republics of the former Soviet Union (Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, and Ukraine) or part of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FYR Macedonia and Serbia). All emerged from communist systems (either Soviet or Yugoslav) and have experienced disintegration followed by transition and continuing change. 3 Although there was alignment between the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia in 1945 immediately after World War II, including similarity in central state administration in the health sectors, this ended in 1948. The Soviet Union continued with its centralized health system, while Yugoslavia developed a more decentralized one, after going through alternating cycles of centralization and decentralization until the early 1950s.4

Countries of both the former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia faced many similar problems and often adopted similar responses. All experienced continued restructuring of national health systems and changes in infrastructure, with a general reduction in the health care workforce.5 Almost all countries faced diminishing public resources available for health services and changes in health care financing.6 Rising poverty levels in most countries impacted the population’s ability to pay for services that were once free, leading to problems with equity and access to basic health services. Corruption in government and regulatory structures further exacerbated problems with equity and access.7 These various factors contributed to a general disintegration in health status and decreases in life expectancy.8

Former Yugoslav countries further faced the trauma of civil war, ethnic cleansing, sanctions, and NATO bombing. War resulted in destruction of hospitals and negatively impacted the delivery of health care services. In 2012, the Commissioner on Human Rights for the Council on Europe characterized the civil war in former Yugoslavia as the period with the greatest human rights and humanitarian law violations in Europe since World War II.9 Physicians for Human Rights had provided a similar assessment.10

Countries of the former Soviet Union further have had to contend with a legacy of collusion between the medical establishment and the state in violations of rights. Doctors practicing in the Soviet Union, in fact, had to swear an oath of loyalty to the state.11 Egregious abuse of medical care for political purposes included psychiatric confinement of political opponents.12

Additionally, both the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia collapsed at the time of the “new age of infectious disease,” with its implications for the policing functions of public health and its differential impact on marginalized populations. In post-Soviet countries, particularly Russia, there has been a drastic rise in mortality due to new or re-emerging infectious diseases such as HIV and tuberculosis.13 As Emma Jolley and her co-authors point out, the HIV epidemic has had a disproportionate effect on “populations who are socially marginalized and whose behavior is socially stigmatized or illegal.”14 The population of people who inject drugs in EECA is one of the fastest growing in the world and accounts for two-thirds of all HIV diagnoses in Europe (70% in Russia).15 The rise in drug use has led to police crackdowns with negative consequences for health.16 Fear caused by criminal laws banning syringe provision and requiring government registration of all even suspected of drug use drives those who use drugs away from life-saving HIV prevention and treatment, as well as other health services.17 It further fosters risky behavior such as needle-sharing, which facilitates transmission of HIV, hepatitis B and C, and tuberculosis.18 Additionally, restrictions or bans on essential medicines designed to combat illicit drug use hamper needed substitution treatment for people with opioid dependence and condemn millions of cancer and other palliative care patients to unnecessary pain and suffering.19 Health professionals are also impeded in their work “within a legal and policy framework that is often in direct conflict with fundamental medical ethics—not least the commitment to ‘first, do no harm,’” as noted by the nongovernmental organization (NGO) Count the Costs.20

The impact of the “war on drugs” is just one of many examples of the unintended consequences of government policies on the health of individuals and the community. The policing function of public health is not new, and its power to curb individual rights—whether to curtail smallpox or tuberculosis—has historically been vast.21 Today, international bodies have determined that infectious diseases rise to the level of threats to international security, and there is again discussion of the “medical police” function of sovereign power.22 It is, however, critical for a human rights analysis to inform these discussions and guide any restrictions.23

EECA countries in transition continue to struggle to meet these challenges to health care access and equity and to define adequate frameworks for protecting basic rights and quality in the delivery of health care. These frameworks include law reform, as well as effective implementation of existing laws on informed consent, confidentiality, privacy, and non-discrimination in the health care arena.24 Both Macedonia and Serbia are candidate countries for accession to the European Union (EU) and have adopted or harmonized laws required by the accession process. The political criteria to be met include the stability of institutions safeguarding democracy, the rule of law, human rights, and protection of minorities.25

Medical, public health, and law schools seeking to incorporate these rapid changes into their curricula have presented a particular opportunity for human rights education. EECA law, medical, and public health schools have been reformed, established, or expanded just as the rights-based approach to health has matured globally and in the West, translating into formalized health and human rights curricula.26 EECA faculty were thus open to new approaches and well positioned to take advantage of lessons learned and state-of-the-art methods in this arena.

The higher education initiative described below attempts to assist EECA faculties of medicine, law, and public health to integrate these lessons and methods and adapt them to their distinct local context. Incorporating human rights in patient care into the professional training of medical and legal personnel develops an understanding of the interconnectivity and human value of all the stakeholders—patients, doctors, health managers, and others, as well as the role of the state. Jennifer Leaning articulates it succinctly: “There is perhaps no better place to begin to impart an awareness of human dignity than in the small world of the doctor-patient relationship.”27

Developing human rights in patient care courses

The Law and Health Initiative (LAHI) of the Open Society Public Health Program, in collaboration with other OSF partners, has attempted to respond to the need to build health and human rights capacity by supporting the development of over 25 courses in law, human rights, and patient care in nine EECA countries: Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Macedonia, Moldova, Russia, Serbia, and Ukraine. Targeted at different audiences and of varying levels of sophistication, these courses are now sustainable and part of the regular offerings at the academic institutions where they are taught.

The initiative began in 2007 when LAHI hosted a seminar as part of the Salzburg Medical Seminar series in Austria. The seminar brought together medical, public health, and law faculty from six EECA countries along with key partner NGOs and patient advocates. Participants spent an intensive week examining critical human rights in patient care topics and thinking creatively about how to structure a course addressing these issues. Topics explored included the international framework for health and human rights; patient privacy, consent, and confidentiality; institutionalization and the health care system; criminalized populations and disease vulnerability; providers’ rights and their relationship to patients’ rights; legal remedies for health care abuses; and human rights in health care reform. While faculty from countries that joined this initiative at a later point did not attend the seminar, they also drew on the seminar resources.

Faculty participants subsequently developed proposals for courses tailored to their national context and target audience. Target audiences varied, including medical students, medical practitioners, nurses, health managers, public health students, and law students. LAHI and OSF partners provided one year of support for the development and piloting of the courses, contingent on institutional backing from the host university and the understanding that if piloting was successful, the courses would then be a regular part of the offerings at each university. To qualify for funding, courses did not need to focus exclusively on human rights in patient care. In many of the countries, law and health (often called “medical law” in the region) itself was a new field, and such an exclusive focus would not have been politically viable at the various institutions. However, to join this initiative, human rights in patient care had to be a central component of the proposed course.

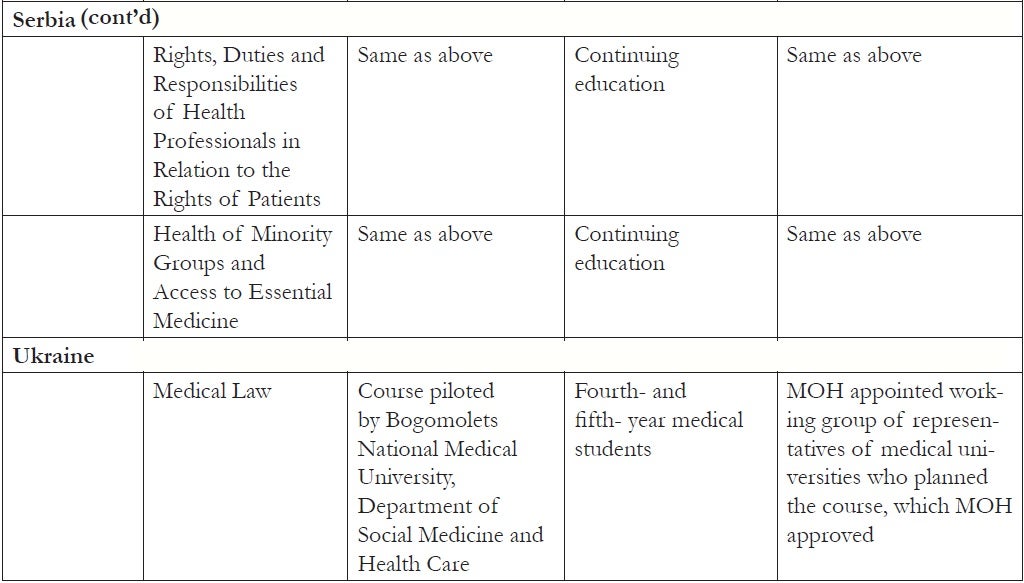

While the development of courses in most of the countries followed the above route, partners in Ukraine took a different approach: developing a course in medical law to be introduced into all the medical universities with Levels III and IV accreditation. This resulted in a larger working group with 27 members representing various medical universities, more levels of review and approvals, and a two-year process lasting to 2009. The Minister of Health created and convened the working group by ministerial order in 2007, with other working sessions held at one of the national universities. On October 19, 2009, Minister of Health Order No. 749 approved and introduced a new curriculum for training in the following areas: general medicine, pediatrics, and general medicine and prophylaxis (preventive health care).28 This included medical law, with components of human rights in patient care, to be taught to fourth- and fifth-year medical students.

Parallel to this initiative, in Romania, OSF’s Roma Health Project partnered with the Association for Development and Social Inclusion (ADIS), a Romanian NGO, to develop courses on non-discrimination and ethics in four medical schools in Romania. These courses address ethics in human subjects’ research, the rights to health and non-discrimination, mechanisms for protection at both the Romanian and European levels, and Roma history and traditions.29

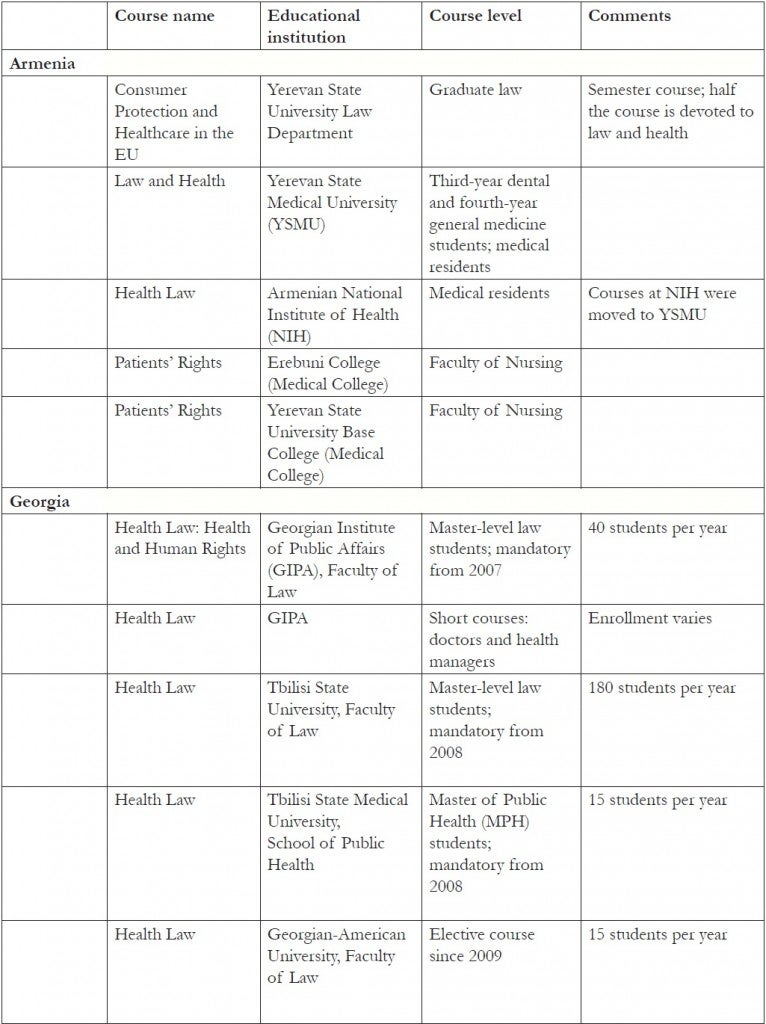

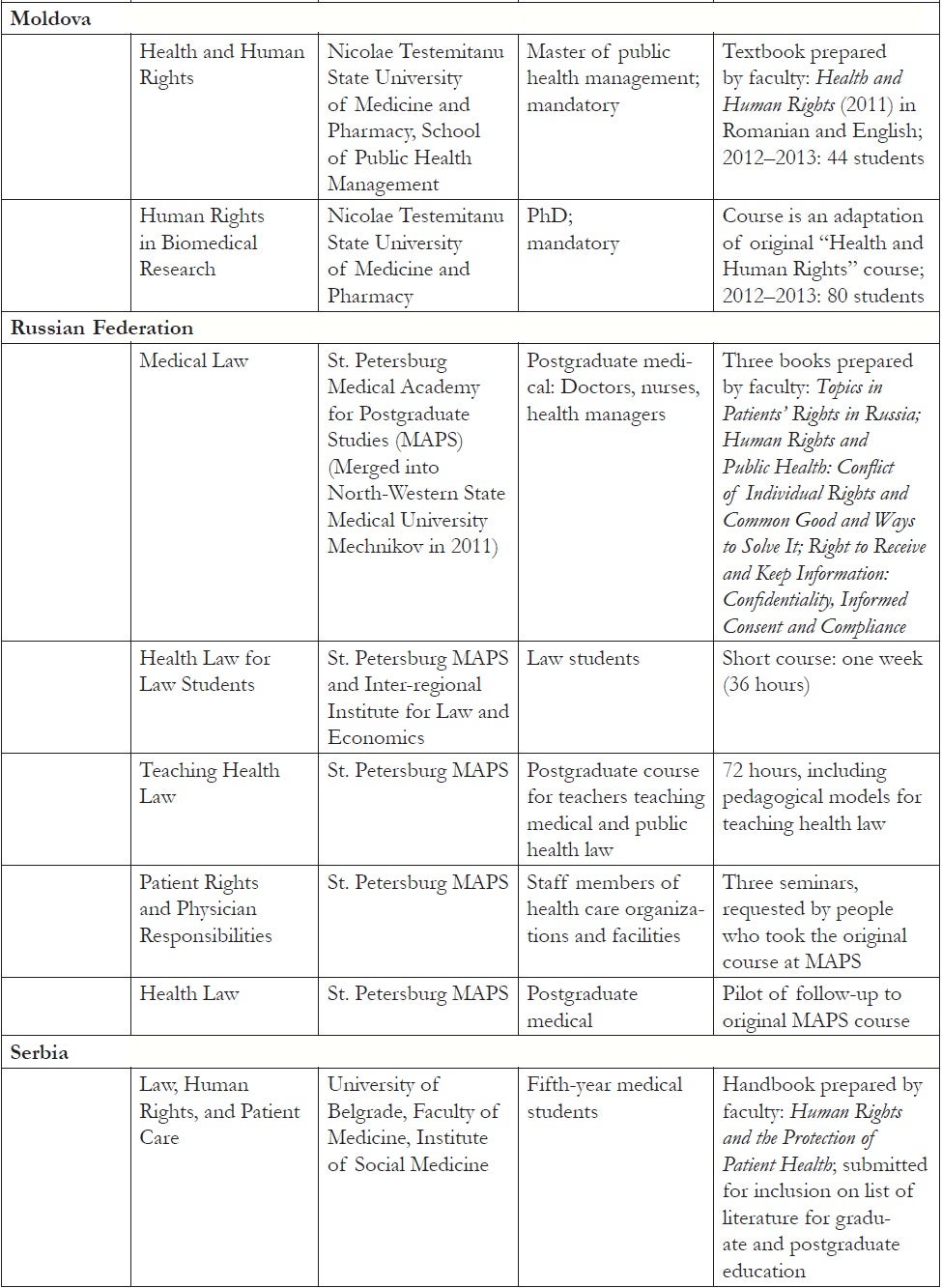

Table 1, shown at the end of this paper, provides a summary of the courses directly developed as part of OSF’s human rights in patient care initiative. All of the courses created course materials and manuals, with some also compiling textbooks. Most of the courses are housed in faculties of law, medicine, or public health (including health management). Two are taught in medical colleges for nurses. They are taught at varying educational levels: master-level law; basic/undergraduate, residency, and postgraduate medical; basic-level nursing; and master-level public health and health management. Number and type vary by country.

The highest numbers of law students are taught in Georgia. As Table 1 shows, there is also a course in the school of public health at the state medical university in the capital, Tbilisi. Georgia is unique in its approach of preparing one basic curriculum (Health Law: Health and Human Rights) and modifying it for the particular student target audience. They also have one core faculty for all the courses—a mixture of legal and medical/health care professionals—with guest lecturers for particular target groups. The course at the school of public health best covers the tensions and synergies that arise between public health interventions and human rights.

Other countries have a variety of courses, as Table 1 shows, with most courses being in medical faculties or schools of public health. There are three others in law faculties and two more that are joint courses between law and medical faculties.

The development of these courses has produced a ripple effect, with other faculty inspired to adopt topics and materials on human rights in patient care in their courses. This transfer took place quite naturally at the same institution where interdisciplinary faculty teams developed the courses in the first place, leading to courses taught at both medical and law faculties. For instance, the course at Saints Cyril and Methodius University in Macedonia is a collaboration of the Faculty of Medicine/Center of Public Health and the Faculty of Law. The course is taught separately to graduate-level law and public health students, with faculty members from both faculties teaching. Once the core curriculum for the course was in place, junior faculty came on board to help teach, thus also entering the field.

Likewise, courses spread to involve students at different levels. In the Kazakhstan School of Public Health, the original course for health managers in the Master Program of Public Health was designed for second-year students. However, student response to the course was so positive that faculty determined a course was needed for first-year students. In Armenia, the state medical university in Yerevan, which initially developed a course for medical residents, added the course for upper-level dental and general medicine students as well. Initial plans for a law, human rights, and patient care course in Serbia focused on upper-level medical students. However, the medical faculty opted simultaneously to design and pilot three continuing education courses, all open to doctors, pharmacists, nurses, lawyers, economists, and public health professionals as members of multidisciplinary teams. All four courses have been nationally accredited, and the course guide was submitted in September 2013 for inclusion in the literature list for graduate and postgraduate education in Serbia.

The new field of human rights in patient care also sparked broader interest by other universities in the country. In Kyrgyzstan, the course for health managers and health care decision-makers was introduced into the curriculum of a national institute for continuing professional education, with later development of a separate department to institutionalize the course. Soon afterwards, faculty at the Kyrgyz-Russian Slavic University developed a mandatory law and health course for civil law students: the project included training for staff and students at the university’s legal clinic to assist with claims of human rights violations in the health care arena. The Kyrgyz State Academy of Law, on its own initiative, developed and piloted a medical law course that includes human rights-in-patient-care components. After faculty successfully offered this course over two academic years, the Academy decided to include it in the regular university curriculum. The university then coordinated an initiative across various law faculties in the country, sharing materials developed and seeking Ministry of Education inclusion of the course in the list of mandatory courses for law curricula. In Armenia, following up on a successful course at the state medical university in Yerevan, two medical colleges developed courses for nurses—the only two courses specifically for nurses set up as part of this initiative.

In Russia, an initial course on human rights in patient care similarly spread to have wider reach. Participants in the original course at the then St. Petersburg Medical Academy of Postgraduate Studies (MAPS), now part of North-Western Russia Medical University Mechnikov, requested three seminars for their co-workers at health care organizations and facilities. Then, a second course, for law students, was prepared jointly with the Interregional Institute for Law and Economics. Faculty then created a separate course for teachers who address health law problems in their courses from various academic institutions. The faculty also prepared three short textbooks.

The above examples illustrate how well the courses have been received. Written participant evaluations combined with evaluation site visits consistently showed mostly positive reactions. In one elective course, since the course was not mandatory, on-site evaluators asked why students took the course; the students overwhelmingly responded that they needed to know this material. Those training to become health managers found the knowledge essential for management positions in health care facilities, dealing with rights and responsibilities of both patients and health care providers, while complying with state regulations. Those already in decision-making roles in health facilities were quite vocal that the postgraduate-level courses should be longer. Medical students and residents also often agreed that courses should be longer, although difficult to integrate into the busy medical curricula. Principles such as confidentiality, privacy, and informed consent were of interest to doctors, medical students, and health managers when approached through a human rights lens. At the outset, some students expressed uncertainty about paying special attention to marginalized groups, rather than keeping a broad focus on the human rights of patients generally. However, during the course, they unpacked the principle of non-discrimination and learned to appreciate the particular health challenges facing marginalized populations.

Course evaluations consistently stressed the need for practical experience and exercises. Students explained that although they must understand theory, “real life” examples and case studies, including actual legal cases and video where these exist, are most effective. One challenge for faculty is that few legal cases exist yet at the national level in these countries. However, students found the use of relevant European Court of Human Rights cases particularly valuable.

Additionally, students appreciated the interdisciplinary team approach to teaching these courses and interaction with multiple perspectives. Students had the opportunity to hear from doctors, bioethicists, ombudspersons, Ministry of Health staff, and directly from members of marginalized groups, as well as from lawyers and law professors. In Georgia, students remarked on the power of having a sitting Supreme Court Justice and a former president of the national bar association articulate the importance of human rights in the delivery of health care services and lead related exercises in class.

Students particularly praised the use of interactive teaching methodology. Some of the most popular exercises required doctors and medical students to assume the role of patients, patients’ family members, or representatives in a role play, or that of lawyer or judge in a moot court exercise. Professors similarly recognized how “walking a mile in another person’s shoes” helped students to grasp the complex interplay of law and medicine in human rights in patient care, with its inherent tensions and, sometimes, competing interests. Consequently, professors (even those with practical experience and degrees in both law and medicine) continued to request training and materials on interactive teaching.

Developing a community of practice

At the outset, LAHI and OSF partners envisioned the successful development of courses to be the end of the initiative. However, they were soon beset with faculty requests for help in strengthening their teaching and for greater connection with their peers. The various faculty members involved in this initiative were pioneers in their countries and craved contact with experts, as well as a community with whom to share ideas, materials, and experiences. As mentioned earlier, there were many requests for resources to assist in interactive teaching. Faculty sought not just scholarly articles and readings on human rights in patient care, but also exercises and other interactive materials they could use.

To meet this need, LAHI and OSF partners organized a series of workshops in the period from 2009 through 2012 for faculty to share materials and experiences with each other, interact with international experts, and jointly develop lesson plans and case studies. Workshop topics have included human rights and health care privatization; access to pain relief and essential medicines; health care and people who use drugs; limitations on human rights in the name of public health; and physician dual loyalty and human rights (for which the guidelines of the International Dual Loyalty Working Group provided an important resource).30 Workshop topics were taught through a variety of different methods, including role plays, games, debates, brainstorming, needs assessments, film, and guest speakers, enabling faculty to experience and experiment with different interactive teaching methodologies. Peer learning during the workshops has also been critical. Faculty themselves led many of the workshop sessions and taught “master classes,” which colleagues could then adapt and use.

LAHI further supplemented materials produced by faculty themselves through the workshops. To meet the consistent demand for case studies, LAHI partnered with the Health Equity and Law Clinic at the Faculty of Law, University of Toronto and with the Hastings Center to develop a series of case studies on cutting-edge health and human rights topics. Issues explored included access to sex reassignment surgery in relationship to legal identity change, access to maternal care for women who use drugs, and coercive sterilization of women living with HIV.31 Additionally, faculty drew on materials produced through parallel LAHI initiatives in their teaching. LAHI and OSF partners supported the development of Practitioner Guides, or practical manuals for lawyers taking human rights in patient care cases, in many of the same countries involved in the courses. These manuals examine patient and provider rights and responsibilities and procedures for protection at national, regional, and international levels.32 Thus, in addition to information on the international and European framework, they provide a human rights analysis of national level laws and procedures, which faculty incorporated in the courses.

Complementing in-person workshops, LAHI and OSF partners also supported the development of an online Community of Practice (available at http://cop.health-rights.org/teaching/) faculty to stay in contact more regularly and for greater sharing of resources. In addition to housing all workshop materials, as well as materials developed by the faculty themselves, the Community of Practice includes curated topical modules with articles and exercises, a section on teaching methodology, and a section with links to relevant films specifically requested by faculty.33 In collaboration with NGO partners, OSF is currently producing a series of videos focused on work protecting the rights of patients from socially marginalized groups, which will be added to the website. Videos feature Roma patients in Macedonia, transgender persons in Ukraine, homeless people living with HIV in Russia, and patients marginalized because of their illness, including cancer patients in Armenia and hepatitis C patients in Georgia. Traffic on the Community of Practice website is particularly heavy at the start of a new semester. For instance, in January 2013, the site received over 3000 visitors with the highest numbers from Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Macedonia (in that order). By June 2013, the highest numbers of users were from the US, Ukraine, Russia, Kazakhstan, and the United Kingdom (in that order); there were users from 110 countries (and an additional 187 users for whom countries were not identified).

Reflections

Critical to this initiative has been working with faculty champions for the field of human rights in patient care at each university. While OSF hosted the initial seminar and provided start-up funding for the development and piloting of courses, faculty drove the project forward. Faculty champions were able to navigate administrative hurdles and the internal politics of each university to get their courses approved and integrated into core university offerings. In some cases, as in Ukraine, this also meant negotiating with government ministries. OSF staff and consultants did not attempt to collaborate with the university administration themselves. Rather, they took a more bottom-up approach, working directly with faculty and investing in building their substantive capacity. Faculty were not shy in letting LAHI and OSF partners know what they needed and what capacities they wanted to strengthen. Their requests led OSF to move beyond the initial vision to development of a multi-year second phase focused on building a community of practice, both virtually and in-person through the series of teaching workshops.

The bottom-up approach taken by this initiative has also led to variation amongst the different courses. While they all have a central component of human rights in patient care, they differ in emphasis, depth, breadth, and teaching methodologies. This initiative has provided much room for local input. The strength of this approach is that it allows for ownership by the faculty who can tailor the curriculum to their particular country contexts and target audiences. This latitude, however, can also lead to uneven quality, making capacity-building for faculty critical.

Since many of the courses include a component on human rights in patient care within a larger law and health course, there at times could be tension between OSF’s desire to narrow and focus on human rights and the universities’ desire to teach a broad course with wide appeal. Faculty negotiated this tension with varying results. Some courses are stronger in human rights than others, depending on both context and faculty capacity. In many instances, human rights have become the frame for addressing all the law and health issues covered in the course. This overarching framework has provided an opportunity to define a human rights approach to a number of different health issues, and the tension between human rights and broader law and health issues has become a source of creativity. For instance, in Georgia, faculty pointed to the importance of paying careful attention to rights protections when designing health insurance regulations.34 Other faculty looked at the implementation of new health technologies and blood/organ donation through a human rights lens.

Absorption of the human rights framework also differed by country. There was particular enthusiasm for the human rights framework and incentives for its adoption in schools in Macedonia and Serbia, at least partially due to their EU candidate status and its corresponding requirements. In these countries, there was also greater flexibility for the development of new courses, despite the need to meet certain standards and adhere to institutional bylaws. Ukraine was at the opposite extreme in terms of flexibility, where faculty in collaboration with the Ministry of Health took a more centralized approach, convening a working group to develop a course for all medical universities with approval of the curriculum required at the Ministry level. Georgia was the most receptive to instituting courses in law faculties; most other courses focused on medical students. Additionally, schools in Eastern European countries showed particular interest in the application of European Court of Human Rights cases and their impact on the law and health framework.

OSF realized early on in this project that teaching methodology is as important as content. Human rights cannot be adequately taught through classroom lectures. A human rights analysis requires more than memorization of a set of norms. As Nancy Flowers writes, “Human rights education must be more than knowledge about human rights documents. It must involve the whole person and address skills and attitudes as well.”35 Students need to grapple with difficult questions, and the voices of people from marginalized communities need to be brought into the classroom. As one professor explained, students need to “feel the problems marginalized communities face by working directly with them. They can then understand, appreciate, and personalize these problems. They become real, not classroom theories.”36 Human rights education literature, therefore, stresses the need for experiential learning and methodologies, such as case studies, site visits, and role plays that promote critical thinking.37 As part of this initiative, professors from EECA countries where didactic teaching is the norm immediately recognized this gap, requesting particular support in this area. As a faculty member from Kazakhstan recounted, “lecturing gives a great opportunity to receive much knowledge, but it does not involve the class in discussion, in analyzing cases, etc. Interactive teaching makes education more alive.”38 Thus, this initiative became as much about how to teach as it was about what to teach.

In order to identify best practices for meaningfully engaging with health practitioners on human rights questions, in parallel to this initiative, LAHI convened an expert consultation, “How Can Training of Health Providers Be Effectively Used to Promote Human Rights in Patient Care?” with global human rights trainers, many with a health background, who have focused on working with health providers. Out of the consultation emerged 10 key principles of human rights education for health care providers.These key principles are:

Do not engage in training for its own sake. Rather, training should be part of a broader initiative.

- Training should be action-oriented and connected to advocacy.

- Always plan for follow up.

- Connect training to the daily practice of health providers. Human rights should be made concrete.

- Involve opinion leaders and identify leaders at different levels in the health system.

- Bring the voices of the patients and the marginalized into the training.

- Use interactive, participatory adult methodology.

- Recognize provider rights and allow space for health providers to talk about their challenges.

- Use peer-led trainings.

- After the training, create benchmarks, checklists, or visual reminders to help integrate human rights into health practice.39

Faculty have taken many of these recommendations to heart in their teaching.

Thus far, the initiative has tended to focus more on health practitioners than legal professionals. Human rights in patient care appeared immediately relevant for health care providers, who interact with patients on a daily basis. Law school students needed a clear connection to practice. The idea emerged of linking law courses to a law clinic where students would have the opportunity to take on practical cases. An example of this is the Medical Law Clinic at Donetsk National University in Ukraine, where students provide legal consultation and representation to patients whose human rights were violated in the delivery of health care.40 Work is also underway for a clinical component in Kyrgyzstan. For most of the courses in law faculties, however, this component has not yet been developed.

More could also be done with the junior faculty involved in courses teaching human rights in patient care. An unanticipated benefit of this initiative has been the ripple effect with faculty colleagues and junior faculty entering the field and incorporating human rights in patient care in their teaching. Junior faculty members, who have not yet established their careers and fields of expertise, may be an important source of creativity to advance this work and ensure its sustainability.

A major gap that this initiative has not yet been able to address adequately is the dearth of scholarly research and writing on health and human rights from EECA countries. Some of the reasons for this are linked to the state of scholarship in this region in general. An important next step for the establishment of human rights in patient care as a vibrant field in these countries would be for it to serve as the subject of serious scholarly inquiry. Over the last few years, the teaching of human rights in patient care has come a long way in EECA countries. During the next few years, perhaps scholars and practitioners from this region will also serve as initiators in the global health and rights conversation, propelling innovation and progress.

Following discussions with LAHI, the Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region (ASPHER) has agreed to institutionalize this initiative under its auspices. ASPHER’s leadership will enable greater sustainability, more local control, and wider dissemination of the human rights in patient care concept. ASPHER, an association with over 100 institutional members and over 5000 academic and expert individual members throughout Europe, aims to support the professionalization of the public health work force through building capacity in public health education, research, and practice. ASPHER’s list of core competencies for public health professionals encompasses the application of law and regulations, human rights, and medical ethics; many ASPHER member schools include lawyers as faculty members. ASPHER already has a strong connection with OSF’s human rights in patient care work in EECA. Ten of the 25 human rights in patient care courses that are part of the OSF initiative are taught in ASPHER member schools. Two members of ASPHER’s board are part of the courses initiative, including ASPHER’s President, Vesna Bjegovic-Mikonovic, who will be serving until November 2015 and whose university has developed four law, human rights, and patient care courses in Serbia.

In assuming leadership of this initiative, ASPHER has agreed to pursue the following:

- Initiate an annual summer school for teachers of law, human rights, and patient care: While OSF has held faculty workshops in the past, an annual competitive summer school program with a few focus topics each year would enable both deeper and wider engagement with faculty. Faculty could spend more time delving into particular substantive areas and developing relevant teaching exercises. A regular event would also provide greater reach, bringing new faculty into this initiative. An interdisciplinary steering committee with both law and health backgrounds, drawn from current human-rights-in-patient-care faculty, would guide the development of the summer school program.

- Assume management of the web-based community of practice: The integration of the Community of Practice on human rights in patient care with ASPHER’s other web resources, such as the Online Resource Centre for Public Health Education and Training, would enable it to be more sustainably maintained and widely disseminated.

- Establish a mentorship program for junior faculty on research and scholarship: This program aims to develop the expertise of junior faculty and address the current dearth in research and scholarship on health and human rights from EECA. Each year, four junior faculty members would be competitively selected as scholars and assigned research mentors. The scholars would then prepare at least one paper for presentation at the annual ASPHER and European Public Health Association conference and for publication in a journal. New thinking and materials could then be incorporated into classroom teaching.

- Establish a core ASPHER network on human rights in patient care and widely integrate this topic in ASPHER schools: ASPHER would form a core network on human rights in patient care, composed of member faculty and universities who teach this topic, which would develop and implement a strategy for integrating human rights in patient care throughout ASPHER member schools and raise the profile of this work. A master’s program in human rights in patient care may eventually be possible.

OSF hopes this next stage of this initiative will build on the past few years of work and lead to a new generation of practitioners committed to the protection of human rights in patient care.

Table 1. Courses developed in EECA countries as part of the human rights in patient care initiative

Tamar Ezer, JD, LLM, is the Senior Program Officer at the Law and Health Initiative of the Public Health Program at the Open Society Foundations in New York, New York.

Judy Overall, MEd, MS (Health Administration), JD, is the lead consultant for Human Rights in Patient Care projects of the Law and Health Initiative of the Public Health Program at the Open Society Foundations, an adjunct faculty member of Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Senior Advisor to the Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Norway.

Please address correspondence to the authors c/o Tamar Ezer, Open Society Foundations, 224 West 57th Street, New York, NY 10019, USA, email: tamar.ezer@opensocietyfoundations.org.

References

1. See, for example, Central and Eastern European Harm Reduction Network (CEEHRN), Sex work, HIV/AIDS, and human rights in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia (Vilnius, Lithuania: CEEHRN, 2005). Available at http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/sex%2520work%2520in%2520ceeca_report_2005.pdf; Mental Disability Rights International, Torment not treatment: Serbia’s segregation and abuse of children and adults with disabilities (Mental Disability Rights International, 2007). Available at http://www.disabilityrightsintl.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/Serbia-rep-english.pdf; Open Society Foundations, Access to health care for LGBT people in Kyrgyzstan (Open Society Foundations, 2007). Available at http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/kyrgyzstan_20071030.pdf; Open Society Foundations, Human rights abuses in the name of drug treatment: Reports from the field (Open Society Foundations, 2010). Available at http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/treatmentabuse_20090309.pdf; Open Society Foundations, Roma health rights in Macedonia, Romania, and Serbia: A baseline for legal advocacy (2013). Available at http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/roma-health-rights-macedonia-romania-serbia-20130628.pdf.

2. L. Beletsky, T. Ezer, J. Overall, et al., Advancing human rights in patient care: The law in seven transitional countries (New York: Open Society Foundations, 2013), p. 16. Available at http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/Advancing-Human-Rights-in-Patient-Care-20130516.pdf.

3. F. W. Neal, “The communist party of Yugoslavia,” American Political Science Review 51/1 (March 1957), pp. 88–111. Available at http://journals.cambridge.org/article_S0003055400070714.

4. N. Simmons, O. Brborovic, T. Fimka, et al., “Public health capacity building in Southeastern Europe: A partnership between the Open Society Institute and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,” Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 11/4 (2005), p. 352. Available at http://nciph.sph.unc.edu/cvs/baker/pdfs/118.pdf.

5. A. Zoidze, G. Gotsadze, and S. Cameron, “An overview of health in the transition countries,” International Hospital Federation Reference Book 2006–2007 (Bernex, Switzerland: IHF, 2006), pp. 29–32. Available at http://www.researchgate.net/publication/233945963_AN_OVERVIEW_OF_HEALTH_IN_THETRANSITION_COUNTRIES/file/32bfe50d3661a918ab.pdf.

6. Ibid.

7. L. Beletsky et al. (see note 2), p. 2.

8. J. P. Mackenbach, M. Karanikolos, and M. McKee, “The unequal health of Europeans: Successes and failures of policies,” Lancet 381/9872 (2013), pp. 1125–1134. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62082-0.

9. N. Muiznieks, Commissioner for Human Rights, Council of Europe, “Post-war justice and durable peace in the former Yugoslavia,” Issue Paper 1 (Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe, March 2012), p. 9. Available at https://wcd.coe.int/ViewDoc.jsp?id=2052823&Site=COE.

10. Physicians for Human Rights (PHR), War crimes in the Balkans: Medicine under siege in the Former Yugoslavia 1991–1995 (Boston, MA: PHR, May 1996). Available at http://physiciansforhumanrights.org/library/reports/medicine-under-siege-yugoslavia-1996.html.

11. P. Tichtchenko, “Resurrection of the Hippocratic oath in Russia,” Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 3 (1994), pp. 49–51.

12. S. Yanokvsky, “Neoliberal transitions in Ukraine: The view from psychiatry,” Anthropology of East Europe Review 29/1 (2011).

13. United States National Intelligence Council National Intelligence Estimate, “The global infectious disease threat and its implications for the United States,” National Intelligence Council 99-17D (January 2000). Available at http://www.fas.org/irp/threat/nie99-17d.htm.

14. E. Jolley, T. Rhodes, L. Platt, et al., “HIV among people who inject drugs in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia: A systematic review with implications for policy,” BMJ Open 2/5 (2012). Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3488708.

15. Ibid.

16. A. Sarang, T. Rhodes, N. Sheon, et al. “Policing drug users in Russia: Risk, fear, and structural violence,” Substance Use and Misuse 45/6 (2010), pp. 813–864. Available as author manuscript at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2946846/; E. Jensema, “Human rights and drug policy,” Transnational Institute (October 11, 2013). Available at http://www.tni.org/briefing/human-rights-and-drug-policy; see also Anand Grover, UN Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, “Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health,” UN Doc: A/65/255 (2010).

17. T. Rhodes, L. Platt, A. Sarang, et al., “Street policing, injecting drug use and harm reduction in a Russian city: A qualitative study of police perspectives,” Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 83/5 (2006), p. 911 and Human Rights Watch, Rhetoric and risk: Human rights abuses impeding Ukraine’s fight against HIV/AIDS (New York: Human Rights Watch, March 2006), vol. 18:2D, as cited in Public Health Program, Open Society Institute, “Public health fact sheet: Police, harm reduction, and HIV” (April 2008). Available at http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/Police%2520and%2520Harm%2520Reduction_ENGLISH.pdf.

18. Count the Costs, “Threatening public health, spreading disease and death,” p. 6. Available at http://www.countthecosts.org/sites/default/files/Health-briefing.pdf.

19. E. Jensema (see note 16); Count the Costs (see note 18), p. 9.

20. Count the Costs (see note 18), p. 2.

21. R. Bayer, “The continuing tensions between individual rights and public health: Talking point on public health versus civil liberties,” European Molecular Biology Organization Reports 8/12 (December 2007), pp. 1099–1103. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2267241/.

22. P. E. Carroll, “Medical police and the history of public health,” Medical History 46/4 (2002) pp. 461–494. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1044561/?page=1; R. Pereira, “Processes of securitization of infectious diseases and Western hegemonic power: A historical-political analysis,” Global Health Governance 2/1 (Spring 2008). Available at http://ghgj.org/Pereira_%20processes%20of%20securitization.pdf.

23. S. Abiola, “Limitations clauses in national constitutions and international human rights documents: Scope and judicial interpretation,” research memorandum prepared for Open Society Institute’s Public Health Program Law and Health Initiative (April 2010). Available at http://cop.health-rights.org/teaching/46/Limitation-Clauses-in-National-Constitutions-and-International-Human-Rights-Documents; S. Abiola, “The Siracusa Principles on the limitation and derogation provisions in the International Covenant for Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR): History and interpretation in public health context,” research memorandum prepared for the Open Society Institute’s Public Health Program Law and Health Initiative (January 2011). Available at http://cop.health-rights.org/teaching/46/Memo-The-Siracusa-Principles-on-the-Limitation.

24. L. Beletsky et al. (see note 2), p. 2.

25. European Union, “The accession process for new member states” (February 28, 2007). Available at http://europa.eu/legislation_summaries/enlargement/ongoing_enlargement/l14536_en.htm.

26. J. Fridli, New challenges in the domain of health care decisions (Budapest, Hungary: International Policy Internship Program, Open Society Institute, 2006), p 11. Available at http://pdc.ceu.hu/archive/00003127/01/fridli_f3; D. Tarantola and S. Gruskin. “Health and human rights education in academic settings,” Health and Human Rights: An International Journal 9/2 (2006), pp. 297–300. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/4065412.

27. J. Leaning, “Human rights and medical education,” British Medical Journal 315 (November 1997), pp.1390–1391. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2127872/pdf/9418078.pdf.

28. Ukrainian Ministry of Health, Ministry of Health Order No. 749 (October 19, 2009) [in Ukrainian; translation by National Medical University of Bogolomets].

29. V. Astarastoae, C. Gavrilovici, M. C. Vicol, et al., Ethics and non-discrimination of vulnerable groups in the health system (Bucharest: Association for Development and Social Inclusion, 2011).

30. International Dual Loyalty Working Group, Dual loyalty and human rights in health professional practice: Proposed guidelines and institutional mechanisms (Boston MA/Capetown, South Africa: Physicians for Human Rights and Schools of Public Health and Primary Health Care, University of Cape Town, Health Sciences Faculty, 2002).

31. See “Health rights community of practice.” Available at http://cop.health-rights.org/teaching/47/.

32. See “Health rights community of practice.” Available at http://cop.health-rights.org/PractitionerGuides.

33. See “Health rights community of practice.” Available at http://cop.health-rights.org/teaching/19/; see ibid., Health rights community of practice.” Available at http://cop.health-rights.org/teaching/17/; see ibid., “Health rights community of practice.” Available at http://cop.health-rights.org/media/200/.

34. Law and Health Initiative, Open Society Foundations, participating faculty members questionnaire responses (2012).

35. N. Flowers, “How to define human rights education? A complex answer to a simple question,” in V. B. Georgi and M. Sebrich (eds.), International perspectives in human rights education (Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Foundation Publishers, 2004), p. 121.

36. As quoted in T. Ezer, L. Deshko, N. G. Clark et al., “Promoting public health through clinical legal education: Initiatives in South Africa, Thailand, and Ukraine,” Human Rights Brief 17/27 (2010), p. 32. Available at http://www.wcl.american.edu/hrbrief/17/2ezer.pdf.

37. See, for example, F. Tibbitts, “Transformative learning and human rights education: Taking a closer look,” Intercultural Education 16/2 (2005), pp. 107–113; L. London and L. Baldwin-Ragaven, “Human rights and health: Challenges for training nurses in South Africa,” Curationis (March 2008).

38. Law and Health Initiative (see note 34).

39. Open Society Foundations, “Expert consultation: How can training of health providers be effectively used to promote human rights in patient care?” (October 22, 2008). Available at http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/publications/expert-consultation-how-can-training-health-providers-be-effectively-used-promote-human.

40. T. Ezer et al. (see note 36), p. 30.