Eric A. Friedman, Lawrence O. Gostin, Kent Buse

Health and Human Rights 15/1

Published June 2013

Abstract

Organizations, partnerships, and alliances form the building blocks of global governance. Global health organizations thus have the potential to play a formative role in determining the extent to which people are able to realize their right to health.

This article examines how major global health organizations, such as WHO, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria, UNAIDS, and GAVI approach human rights concerns, including equality, accountability, and inclusive participation. We argue that organizational support for the right to health must transition from ad hoc and partial to permanent and comprehensive.

Drawing on the literature and our knowledge of global health organizations, we offer good practices that point to ways in which such agencies can advance the right to health, covering nine areas: 1) participation and representation in governance processes; 2) leadership and organizational ethos; 3) internal policies; 4) norm-setting and promotion; 5) organizational leadership through advocacy and communication; 6) monitoring and accountability; 7) capacity building; 8) funding policies; and 9) partnerships and engagement.

In each of these areas, we offer elements of a proposed Framework Convention on Global Health (FCGH), which would commit state parties to support these standards through their board membership and other interactions with these agencies. We also explain how the FCGH could incorporate these organizations into its overall financing framework, initiate a new forum where they collaborate with each other, as well as organizations in other regimes, to advance the right to health, and ensure sufficient funding for right to health capacity building.

We urge major global health organizations to follow the leadership of the UN Secretary-General and UNAIDS to champion the FCGH. It is only through a rights-based approach, enshrined in a new Convention, that we can expect to achieve health for all in our lifetimes.

Introduction

Every now and then, a transformational idea enters the world scene. Human rights were one, promising a new global order based on the equal human dignity of all. International law posed powerful limits on sovereignty, with obligations on how a state must and must not treat its inhabitants, banning long-standing state practices and promising equity in a world rife with inequalities. With their focus on equity, accountability, and empowerment, human rights have the potential to meet the greatest challenges of global health: deep health inequities persist despite aggregate advances, governments inadequately implement their national and global commitments and norm, and people whose needs are the greatest often have little voice in shaping the policies that determine their health and well-being.

Since the 1990s, a second transformation has been under way in the global health architecture that can help make “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health” (the “right to health”) a reality.11 A landscape of far greater complexity has emerged, with new organizations and partnerships, from those focused on standard setting, monitoring, and advocacy to multi-billion dollar financers. This latest transformation engages not only governments, but also civil society, foundations, the private sector, and international institutions.2

Like a federalist system where states can serve as laboratories for democracy, these organizations can be laboratories for advancing human rights norms and processes. These institutions are forging new pathways for human rights, from establishing governance structures that engage marginalized communities to funding advocacy organizations.

Both transformations, however, remain patchy and unfulfilled. Our claim is that institutional support for the right to health should transition from ad hoc and partial to permanent and systemic. A proposed new global health treaty, the rationale for which has been outlined previously and on which we have campaigned, could catalyze and codify this transition. We propose four ways an FCGH could do so.3

First, the FCGH can establish how organizations incorporate right to health standards and commit states to promote human rights within institutional structures. Second, the FCGH could incorporate global health organizations (GHOs) into its overall financing framework, ensuring sufficient, sustained, and predictable financing. Third, the FCGH could initiate a new forum where global health and other institutions collaborate to incorporate best human rights practices in their core values, standards, and operating practices. And fourth, building on an earlier proposal for a right to health capacity fund, we suggest that GHOs incorporate a right to health capacity-building function.4

Given the pervasive effect of GHOs on global health, from funding to norms, we believe that an FCGH would be incomplete without stating how institutions can best achieve their goals. GHO goals generally include dramatically narrowing health inequities, advancing all aspects of the right to health, responding to multiple legal regimes that advance (or undermine) the right to health, addressing health threats that require global solutions, and improving global governance for health, often by enhancing accountability.

We begin by offering an analytic framework of the institutional entry points for a human rights approach. We then build the elements of an international agreement on GHO practices using this framework, employing illustrative examples of existing progressive organizational processes. Finally, we explain how these elements can be brought together into the FCGH and expand on our other FCGH proposals on how GHOs can support the right to health.

Our focus will be on three central human rights tenets: equity and non-discrimination, with particular concern for poor and other vulnerable populations; participation, with special concern for empowering those most likely to be excluded; and accountability, again above all to people traditionally with the least influence to hold governments and powerful actors answerable. Our focus is primarily at the level of organizations with global membership and reach, such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria.

The organizations we focus on have been particularly innovative and influential in proactively elevating human rights, viewing human rights as central to their missions. It is more than coincidence that we place a particular focus on the Global Fund and UNAIDS. In many contexts, rights-based approaches have been critical to enabling access to HIV prevention and treatment, and the AIDS movement has been central to the health and human rights movement itself. We draw upon the experience of other major actors whose practices demonstrate how GHOs can support human rights. With the iterative efforts of the Global Fund, UNAIDS, and other GHOs to continually improve their engagement with human rights, we focus on recent policies and practices.

We aim to draw out good practices to stimulate thinking on how an FCGH could contribute to maximizing the contribution of GHOs to human rights. While our analysis should contribute to spurring a more comprehensive review of the human rights policies and practices of global health agencies, further informing not only an FCGH but possibly near-term reforms as well, a systematic review is beyond our present ambition. Similarly, we have not sought to examine how effectively policy documents we draw upon have been put into practice, but recognize that implementation is crucial, requiring research and action.

With the growing influence of corporations on health—from the health care industry to those in other sectors such as food, energy and resource extraction, and apparel—we recommend a similar exercise to inform the FCGH with respect to health and human rights standards to which corporations, particularly transnational ones, should adhere. Such standards could build on good practices and existing frameworks, such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the Human Rights Guidelines for Pharmaceutical Companies in Relation to Access to Medicines.5

An analytic framework: Organizational entry points for the right to health

Global health organizations can advance the right to health through four key routes. First, by channeling international assistance in ways that respect this right (e.g., assisting marginalized populations), they contribute to the human rights obligation of “international cooperation and assistance” (International Covenant for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights) and to universal observance of human rights (UN Charter).6 Second, GHOs can support human rights by ensuring their operations conform to human rights principles. Embedding these principles within their operations is an end in itself.

Third, GHOs can promote the right to health within states, from the entities they fund (e.g., health and human rights organizations) to the technical support they provide and normative standards they promote. Fourth, GHOs can set rights-based norms through guidelines, policies, and partnerships.

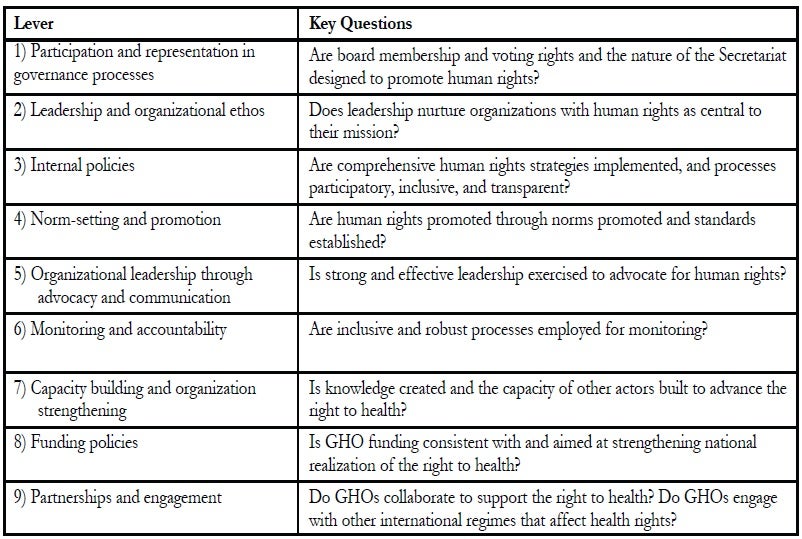

Table 1 identifies nine levers through which GHOs can advance the right to health. We developed these levers inductively, examining policies, practices, and other attributes of GHOs, and seeking to impose an order to allow for systematic examination. We consider such a framework will be useful in future analyses of how GHOs address the right to health. Nonetheless we recognize its imperfections; there are interactions among the various levels, certain policies might be classified in several areas, and there may be actions GHOs can take to support the right to health that do not fit neatly into any of these categories.

Effectuating the right to health through GHOs

Participation and representation in governance processes

Public participation “in all health-related decision-making at the community, national, and international levels” is a vital aspect of the right to health.7 Civil society representation in GHOs can facilitate advocacy on the people’s behalf, channel their demands, and hold GHOs accountable in their funding and activities. We recognize that civil society is diverse and representation of marginalized populations imperfect—with some parts of civil society impeding human rights, such as by urging unequal treatment of sexual minorities. It is therefore important that GHOs ensure a robust human rights presence among civil society representatives.

Civil society and communities must be part of GHO governance structures, including their boards, committees, and advisory panels.8 The Global Fund and UNAIDS have been pioneers, with the Global Fund having two NGO representatives, one from developed countries and one from developing countries, and a communities delegation representing populations living with one of the Fund’s priority diseases.9 UNAIDS is the first UN agency to include civil society on its governing board, with three members from lower-income regions (Africa, Latin America, and the Asia and the Pacific regions) and two from the higher-income regions (Europe and North America). They lack voting rights, though a tradition of consensus-based decision-making has evolved.10

While civil society and community representatives may not perfectly represent their constituents, either entire populations or hundreds of NGOs from much of the world, GHOs should facilitate their genuine participation. For example, civil society and community constituents should choose their own representatives through fair and deliberative processes, and need to have the funding, training, or other support that their full and informed participation may require. GAVI’s plethora of structures is instructive, with a 15-member steering committee to support the civil society board member, an open Civil Society Forum, and a communications focal point to enable broad civil society input.11

The demand for participation also affects government representation in GHOs. Countries in the Global South generally carry the bulk of the ill health burden. In turn, they are also the GHOs’ main beneficiaries. Increasing the number of representatives of Southern governments within GHOs (which should be representing their people’s perspectives and priorities, even as that reality varies greatly) would strengthen Southern countries’ power within the global health sphere and give them more of a voice. GHO representation should capture the diversity among Southern countries and enable the people most in need to have greater political power.

Whether or not governments can legitimately represent all of their inhabitants is a controversial question. Perhaps governments serving on GHO boards should satisfy some basic democratic standards. This could take a loose form and leave ultimate decisions to the GHO boards based on internal selection rules, or there could be more robust criteria that would unambiguously exclude certain country governments. Further, member governments should not have domestic policies that would undermine the GHO’s mission or undercut public health and human rights; as they could obstruct GHO efforts to counter such policies elsewhere. For example, countries that have laws criminalizing homosexuality undermine the Global Fund’s effort to ensure universal access to HIV-related services.

Table 1: Organizational levers to support the right to health

Unfortunately, given the prevalence of punitive laws in many low- and middle-income countries, this principle would be in tension with the need to enhance GHO representation of countries from these regions. One response to this tension would be establishing time-bound benchmarks for legal reform. These benchmarks would enable diversity while simultaneously encouraging elimination of discriminatory laws. Or, given the range of state actions that undermine the right to health—not only discriminatory laws, but other policies such as inadequate budgets and punitive approaches to drug use—a more holistic, flexible approach would be to exclude governments that systematically violate the right to health from GHO boards. This reflects eligibility standards for the UN Human Rights Council.12 It also creates a space for debate on a government’s right to health record and could be an inducement to improve human rights practices.

We recommend that the FCGH include the following elements:

1) GHOs should include civil society and community representatives on their boards and other advisory mechanisms. Representatives should have full voting rights and representation levels sufficient to ensure a meaningful voice and genuine potential to influence policy. It may be possible to include a general benchmark proportion of board members drawn from the Global South and underrepresented and marginalized constituencies.

2) GHOs should support and encourage civil society and community representatives to be as genuinely representative of their constituencies as possible. Such support could include funds for regular communications with their constituencies.

3) GHO governing board selection criteria and processes should take into account governments’ right to health practices and exclude governments that systematically violate the right to health.

Leadership and organizational ethos

For a GHO’s nature to fully reflect human rights, we must look beyond its formal governance model. A culture of rights should infuse the GHO staff and structures, beginning with leadership committed to human rights. Such commitment should inform selection of GHO leaders. Depending on the GHO’s missions, functions, and current challenges, emphasis on this dimension of leadership will vary. For example, whether it produces normative guidance or has a narrow technical remit, or whether its immediate priority is to resolve a crippling budget shortfall can all inform the selection of GHO leaders. Furthermore, a human rights concern needs to be mainstreamed throughout the organization. UNAIDS, for example, includes a commitment to human rights and gender equality as a core staff value.

Training and other measures can educate GHO staff on human rights. The Global Fund’s strategies on gender equality, sexual orientation, and gender identities include improving the gender balance of Fund management and leadership and improving the expertise on sexual orientation and gender identity on its grant Technical Review Panel, the Fund’s proposal review body. Most innovatively, the sexual orientation and gender identities strategy focuses on the Fund’s local governance structures—the Country Coordinating Mechanisms (CCMs), which are responsible for developing proposals. The Global Fund will increase CCM members’ understanding of sexual and gender minorities by linking them with local champions of sexual and gender minority rights and funding CCMs to consult with gender equality and sexual minority experts, organizations, and networks.13

Larger GHOs in particular can develop internal structures dedicated to human rights to facilitate agency human rights capacity building and ensure that human rights fully inform their policies and processes. WHO has a small gender, equity, and human rights office, while UNAIDS has an independent advisory Reference Group on HIV and Human Rights. UNAIDS also has a human rights team at its headquarters, and is increasing human rights capacity in many of its country offices.

FCGH recommendations:

1) GHOs should incorporate human rights expertise and a demonstrated commitment to human rights into hiring criteria.

2) GHOs should strive for gender parity and the inclusion of marginalized and disadvantaged populations among staff and organizational structures.

3) GHOs should build human rights capacity of staff and members of organizational structures.

4) GHOs should develop organizational structures dedicated to incorporating human rights throughout their activities.

Internal GHO policies

GHOs need to develop institutional policies that incorporate human rights. These policies include constitutions and mission statements. WHO’s constitutional principles are exemplary in this regard.14 The mission of UNAIDS includes “speaking out in solidarity with the people most affected by HIV in defense of human dignity, human rights and gender equality,” and includes “zero discrimination” as an element of its vision.

Specific policies are needed to translate a human rights-oriented mission statement into systematic and concrete support for human rights. Comprehensive strategies can ensure a systematic approach. The Global Fund took a step in this direction by elevating human rights to one of its five strategic objectives in its 2012-2016 strategy, which includes commitments to integrate human rights throughout its work, to increase investments in programs responding to rights-related barriers to access, and to ensure that it does not support any programs that violate human rights.15

The human rights issues most relevant to a GHO’s mission may present additional opportunities for rights-based policies. For example, the Global Fund Board established a policy not to convene meetings in countries that restrict entry of people living with HIV.16

Some global agencies with a major role in health also work in other areas, notably the World Bank and regional development banks, bilateral aid agencies, and some foundations. While ensuring that all health-related policies are grounded in human rights, such organizations will need to ensure that other policies respect—and as much as possible promote—the right to health. GHOs can dedicate staff to ensuring right to health policy coherence, improve inter-departmental collaboration, and conduct right to health policy and program assessments.

Human rights are concerned with inclusive, transparent, participatory processes. Are GHO policies and strategies developed through such processes? Different types of policies will require different levels of participation from people outside these organizations. Standard governance policies, such as conflict of interest or investment policies, would likely not require external consultations. Even as these policies may have human rights implications, the inclusion inherent to the internal governance we have described could suffice.

There is no clear line delineating where internal processes suffice and where more extensive consultative processes are appropriate. Resources and other practical considerations will play a role in determining whether internal processes will suffice. Factors that can help identify policies that should be subject to more extensive participation could include those that significantly affect GHO operations, external standards and norms, or marginalized populations.

Social media and other information technology create space for far more inclusive strategy development than heretofore possible. Web-based consultations are becoming increasingly popular. UNAIDS used crowdsourcing and other social media to great effect in its CrowdOutAIDS initiative, garnering participation of more than 5,000 young people in 79 countries in developing recommendations for UNAIDS’ youth agenda.17

Rights-based processes favor transparency, which is central to accountability. Transparency enables scrutiny of GHO policies and the debates behind them. This enables more informed external input and allows for an evaluation of whether civil society and community constituencies are meaningfully engaged and whether their concerns are taken into account as GHOs develop their policies.

Transparency of GHO grants enables public monitoring and is vital to ensuring that GHOs support human rights with their funding. The Global Fund and GAVI post most approved grant applications online, along with annual progress reports (GAVI), disbursement requests, and other related documents (Global Fund). Both could go further by making unsuccessful proposals and assessments of both successful and unsuccessful proposals available to the public.

In some cases, governments may resist full GHO transparency, concerned that certain material (e.g., unsuccessful proposals) may reflect poorly upon them. Prior agreement in the FCGH to support transparency could help. Even so, there could be situations in which GHOs will need to avoid revealing sensitive information. This could include information on organizations they support that operate covertly in specific countries, trying not to gain the attention of the government as they work with marginalized populations who are viewed as criminals or hostile to the state, or simply under the control of the opposition in a highly polarized or conflict-ridden country.

FCGH recommendations:

1) GHOs should formally incorporate the right to health as part of their missions, as well as in their constitutions and by-laws.

2) GHOs should develop right to health strategies to integrate human rights throughout their policies and operations.

3) GHOs whose ambit extends beyond the health sector should ensure that all policies are consistent with and support the right to health.

4) GHOs should have mechanisms to enable people most affected by policies to participate in their development. Whenever possible, these mechanisms should solicit views of marginalized communities.

5) GHOs should maximize transparency.

Norm setting and promotion

Many GHOs seek to influence states and other actors. Some GHOs may have a norm-setting role, and they should ensure that these norms promote human rights. One way that GHOs can use their norm-setting role is by explicitly linking GHO-promoted standards to human rights. For example, the Global Health Workforce Alliance promotes health workforce plans that are “costed and evidence-informed, consistent with human rights principles, including gender sensitivity, and based on projected needs.”18

WHO is presently setting standards on measuring universal health coverage, emphasizing that “on the path to [universal coverage], equity is paramount,” and expressing the need for indicators to “have a strong distributional focus…with disaggregation by the major stratifiers” such as gender and socioeconomic status.19 Right to health principles underlie WHO’s recent high profile policy initiatives in universal health coverage and primary health care for the 21st century.

GHOs may develop norms directly advancing human rights. The AIDS response has led the field, from the 1996 International Guidelines on HIV/AIDS and Human Rights to the 2001 Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS and the outcome documents of UN General Assembly Special Sessions on HIV/AIDS in 2006 and 2011. These guidelines, declarations, and documents set human rights standards and commitments in the context of the HIV pandemic.20 GHOs may need to leverage their technical expertise to develop guidance on how norms can be translated into specific policies and actions.

FCGH recommendation:

1) GHOs should incorporate the right to health and its principles in their norm and other standard-setting activities, along with guidance on how to operationalize these norms.

Organizational voice and leadership through advocacy and communications

GHOs should actively promote rights-based norms. Their communications strategies can emphasize rights-related aspects of their work, related concerns, and ways to redress these concerns. When a Malawi court sentenced two gay men to 14 years of prison and hard labor, UNAIDS issued a press release expressing serious concern and took the opportunity to remind the world that criminalization based on sexual orientation threatened progress in the fight against AIDS and violated human rights, even as more than 80 countries had such laws on their books.21

Rights promotion can take the form of behind-the-scenes engagement and lobbying, where quiet diplomacy may be more effective than public statements. UNAIDS Executive Director Michel Sidibé personally appealed to Senegal’s president to pardon nine gay men, each sentenced to eight years’ imprisonment for “unnatural acts.” Soon afterwards, the charges were dropped.22 Similarly, pressure from the Global Fund outside the public eye may have contributed to China’s decision to review its travel ban on foreigners living with HIV; the review occurred the week before the Global Fund’s board was due to meet there.23

Beyond addressing particular abuses, GHOs should use their prominence and connections to policymakers to urge countries to reform discriminatory laws against women and marginalized populations, and other laws that undermine public health.

On-site GHO board meetings provide opportunities for public human rights advocacy. The board might meet members of marginalized communities to demonstrate solidarity and learn how to better meet their needs.

One challenge GHOs may face in implementing these recommendations relates to maintaining cordial working relations with governments that could view their efforts as unduly interfering with what officials perceive to be domestic, cultural, or sensitive matters. Such tensions may be inevitable. GHOs would do well to work with health and human rights advocates in these countries to navigate them and respond sensitively yet resolutely to human rights concerns.

FCGH recommendation:

1) GHOs should use all advocacy and communication opportunities, including direct engagement with government leadership, meetings with and support for populations experiencing rights violations, and collaboration with other GHOs, to address right to health concerns in countries receiving GHO support. GHOs should collaborate closely with local civil society in these efforts.

Monitoring and accountability mechanisms

Along with using their leverage to advocate for human rights, GHOs must ensure that their own programs promote human rights by including robust processes to monitor country progress. Careful monitoring to ensure that funds are being properly used, programs are advancing equity, and that countries are protecting rights of marginalized populations is central to the right to health. Monitoring and accountability mechanisms help ensure that countries’ stated support for the right to health is backed by actual support.

Transparency is an important aspect of accountability. Transparency opens up possibilities for NGOs, media, and others to detect problems and to insist upon answers to hard questions. Transparency allows civil society to address inadequate progress and unmet commitments, to collectively strategize with governments and GHOs on improving performance, and to challenge official assessments if they are inaccurate or misleading. GAVI provides annual progress reports for each country (submitted by the government) online, while the Global Fund provides disbursement information and grant scorecards and performance reports for each grant. An increasingly transparent World Bank makes a host of project documentation available online.

UNAIDS offers transparency in another vital area. It identifies the countries with laws violating the rights of marginalized populations, including travel restrictions for men who have sex with men, injecting drug users, and sex workers.24 This information can have a classic human rights “naming and shaming” impact, can provide information that enables human rights campaigns to target their efforts, and can highlight countries that have repealed punitive laws to encourage others to follow their lead.

Civil society should monitor GHO-supported advancements or policies so that evaluation of progress is not limited to a government’s assertion or an array of statistics. However valuable, numerical data may be hard-pressed to capture critical dimensions of the right to health. For example, statistics may not demonstrate whether policies to advance the right to health are being implemented comprehensively so as to allow disfavored population access to health services. An accurate understanding of how countries roll out programs and overcome obstacles sets the stage for course corrections to better realize the right to health.

UNAIDS guidelines on biennial country progress reports based on the 2011 Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS emphasize “[t]he importance of securing input from the full spectrum of civil society, including people living with HIV, cannot be overstated.”25 The declaration requires countries to involve civil society, including people living with HIV/AIDS, in monitoring the commitments under the declaration.26

FCGH recommendations:

1) Civil society should have the mandate and capacity to monitor GHO-supported programs and commitments. Such processes should be robust and, in general, include developing benchmarked action plans to accelerate progress where it is lacking.

2) GHOs should make progress reports and similar material publicly available, including through the Internet.

Capacity building and organizational strengthening

GHOs should use their expertise, authority, and coordinating functions to enhance right to health understanding and capacity within countries, and guide countries to policies and practices that best promote the right to health. This can begin by providing information on how the right to health relates to the GHOs’ areas of work, and offering guidance on how to incorporate human rights into these areas. At the most basic level, WHO provides introductory information on health and human rights, while also providing guidance on incorporating human rights and gender equity into national health strategies and integrating several specific health areas.27 The Global Fund offers information notes explaining the importance of human rights in combatting tuberculosis and AIDS, highlighting activities and programs to advance rights, and providing detailed guidance on promoting equity throughout the Global Fund grant lifecycle.28

GHOs can take further steps by facilitating countries in sharing good human rights practices. For example, the Pan American Health Organization was mandated with this task in a 2010 health and human rights resolution. UNAIDS offers case studies of how people living with HIV/AIDS have used the courts to secure their rights.29

Some GHOs may be positioned to directly assist countries in incorporating the right to health into national policies and strategies, perhaps in a policy-advising role or through engaging in national committees informing policy. They could also strengthen processes for joint assessments of national health strategies by national stakeholders and development partners and provide input during these assessments.30

Possible FCGH elements:

1) GHOs should develop guidance for countries on how to incorporate human rights into health policies and programs.

2) GHOs should lend their subject-specific human rights expertise to countries in developing strategies, policies, and programs. Countries should solicit and welcome such advice.

Funding policies

Funding practices of grant-making GHOs can significantly affect the right to health. To improve accountability, equity, and other aspects of the right to health, these GHOs should invest significantly in NGOs, marginalized populations, and human rights structures and processes.

Some GHOs fund NGOs. This is critical given the multiple ways in which NGOs support the right to health, including advocating for and providing health services to marginalized populations, holding governments accountable, and ensuring that funds are used properly. NGOs also work to ensure that both government and private actors adhere to health-promoting policies. They press for effective programs, increased health funding, and policies that advance equity. Furthermore, NGOs can provide oversight for the responsible use of GHO investments.

Several organizations are notable for taking special measures to build the capacity of civil society organizations, as well as community groups and networks. The Global Fund encourages applicants to routinely include measures that strengthen community responses, including “increased demand for and access to service delivery at the local level for ‘key affected populations’—including women and girls, sexual minorities and people who are not reached with services due to stigma, discrimination and other social factors,” and to build their organizational and financial capacity.31

Capacity building and advocacy are at the core of a small but significant International Health Partnership (IHP+)-funded Health Policy Action Fund. This fund aims to enhance the capacity of civil society health organizations and coalitions to participate in national policy processes and hold governments and donors accountable, including to marginalized populations.32

Civil society actions may run counter to what government officials perceive as in the national interest—or even in their own political or personal interests. Therefore, government-driven funding proposals may fail to address the needs of marginalized populations or fail to include finance mechanisms that promote government accountability. Funding applications, even those developed through participatory processes, may not recognize, aid, or include certain marginalized populations that are shunned or discriminated against by large segments of the population.

Where such issues might arise, grant-making GHOs should permit civil society organizations to seek funding outside of the government or government-controlled channels. The Global Fund’s non-CCM application option captures this need, though it is rarely successful in practice. This option is particularly important as GHOs move towards directly funding national health strategies. These health strategies might primarily cover the public sector and leave less space for civil society capacity-building and financial support, particularly funding for advocacy.

Funding NGOs may provide one route to increase resources directed to marginalized populations. Establishing policies to directly channel funds towards these groups is another route. Under the Global Fund’s grant restructuring policies developed in 2012, higher-income countries with lower disease burdens must target the populations that are “most-at-risk.”33 GHOs could also earmark a portion of their funds to address marginalized populations, much as the Global Fund did in its short-lived 2011 funding policy.34

As may be relevant to their missions, GHO focus on marginalized populations should not neglect complex realities of equity. GHO policies should encourage actions across the gamut of inequalities. The policies could be in accord with the principles advocated by Michael Marmot and colleagues, wherein “actions must be universal, but with a scale and intensity that is proportionate to the level of disadvantage.”35

GHOs would do well to consider funding entities from community to national levels that promote accountability. Examples are village health committees, community advocacy networks, and governmental right to health units. GHOs may also support civil society to provide right to health education and training for health workers, legal system personnel, the media, and the public.

A Global Fund grant to Cambodia supported village health committees where community members could voice concerns that would be transmitted to higher authorities in addition to receiving education about health-related rights and how to present health concerns to local authorities. The grant also funded health worker training on patient rights and the development of educational material to inform patients of their rights.36

GHOs should, where possible, address underlying and broader social determinants of health. GHOs have funded schooling, income-generation programs and vocational training for orphans and vulnerable children, people living with HIV, and women in particular. GHOs also work to strengthen legal systems to respond to gender-based violence and protect women’s property and inheritance rights. GHOs can also support countries to develop health information systems like the Health Metrics Network, which disaggregate data by income quintile and other potential markers of disadvantage and marginalization.

In addition to encouraging rights-based activities, GHOs that solicit funding proposals should consider how proposal review criteria and application material can incorporate human rights. The Global Fund now requires several human rights-related analyses as part of country applications, including data on gender and sexual orientation.37 In accordance with a 2011 requirement, grant applicants must conduct (or use existing) country-level assessments of inequities and barriers to reaching underserved populations in developing new proposals and renewing existing grants. These equity assessments will establish a baseline to monitor progress and identify actions required to improve equity. The assessments should draw on multiple data sources, be participatory, and the results should be utilized for planning purposes. The Global Fund also incorporates equity in proposal review criteria.38

GHOs, notably the Global Fund and GAVI, have sought to increase overall investments in health through additionality, co-financing requirements, and innovative financing mechanisms. GHOs should continue to find ways to increase domestic and international health resources, and look to take advantage of additional private sector resources. Increased resources for health may best be secured through an overall FCGH financing framework establishing a paradigm of permanent global solidarity with increased, sustained domestic and international health financing. Assessed contributions for GHOs could be incorporated into this framework.

FCGH recommendations for grant-making GHOs, as applicable:

1) GHOs that provide funding controlled by the government should also enable civil society to directly apply for funding.

2) GHOs should have mechanisms to encourage and prioritize funding to support marginalized and other disadvantaged populations. They should assess the possibility of earmarking funds for this purpose.

3) GHOs should fund capacity building for civil society organizations that advocate for and provide right to health knowledge and access to justice programs.

4) GHOs should incorporate right to health analyses into their funding processes, perhaps as a proposal requirement that will be taken into account upon review.

5) GHOs should evaluate and implement possibilities to expand financial support to address underlying and broader social determinants of health.

6) GHOs with co-financing policies should assess how the policies work in practice, and revise them as needed to better ensure that the policies actually advance the right to health and other human rights.

7) GHOs should explore how innovative financing mechanisms could increase overall health resources, improve health equity, enhance accountability, and otherwise advance the full realization of the right to health.

Partnerships and engagement with other global health institutions

How GHOs interact can reinforce or undermine human rights. When multiple agencies support a single health program or facility, lines of accountability may be blurred. And the multitude of GHOs leads to high transaction costs for countries, reducing the availability of resources towards full realization of the right to health. Efforts like those advanced by IHP+ and the Global Fund to integrate financing and support within overall national strategies, can limit these transaction costs.

Yet the expertise across the spectrum of health niches creates many opportunities to better integrate the right to health into the health system. The array of GHOs creates many possible spaces for civil society and communities to participate in health policymaking—but also challenges the capacity of governments and NGOs, and risks high transaction costs.

Furthermore, fragmentation among GHOs can undermine the right to health. As the IHP+ was preparing its Joint Assessment of National Strategy (JANS) process, many in civil society sought to establish a funding norm among development partners in which any health strategies that scored poorly on human rights would not receive funding, especially if there was a lack of civil society involvement in developing those health strategies. This united front pressured countries to develop human rights-supportive health strategies. Ultimately, IHP+ chose to allow each development partner to decide how to respond to JANS findings.

FCGH recommendations:

1) GHOs should regularly assess how they can most effectively contribute to human rights in their partnerships and other collaborations.

2) GHOs should seek to reduce transaction costs that lessen resources available for health programs.

Partnerships and engagement with other global organizations

GHOs share the international law and policy space with institutions that have different missions; their core concerns may not include health or human rights. These institutions range from the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the trade and intellectual property regimes (which can place the cost of medicines beyond the reach of the poor and limit states in regulating public health) to the Food and Agriculture Organization (with a core health concern of achieving food security, yet rarely considered a GHO). The ability of GHOs to influence other institutional regimes—including investment, the environment, migration, and labor—is critical to realizing the right to health.

GHOs should directly engage these other regimes, working with institutions such as the WTO to ensure that their policies are consistent with the right to health. GHOs can offer policy advice to protect the right to health, as UNAIDS, WHO, and UNDP offer recommendations to countries on taking advantage of flexibilities in the Agreement on Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) to enhance access to medicines.39 GHOs can provide written guidance, workshops, offer webinars, and otherwise build the capacity of national stakeholders to promote the right to health within these other regimes.

GHOs need the capacity and willingness to spend political capital to protect the right to health in these other domains. This poses a leadership challenge, for these organizations are often governed in part by governments that support higher intellectual property protection, profit from state-owned tobacco companies, see coal as central to meeting growing energy demands, or subsidize crops that contribute to unhealthy eating.

One regime that stands to enhance the right to health is the human rights regime, replete with its own machinery. GHOs can make use of the opportunities this creates, bringing human rights concerns to the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to health and the UN Human Rights Council while using their expertise to inform GHO policies. The Council’s Universal Periodic Reviews of state human rights records could cover national efforts to advance the right to health through GHOs, and overall national progress on implementing the FCGH.

Possible FCGH elements:

1) GHOs should engage institutions and policymakers in non-health regimes that have an impact on the right to health. GHOs may need to build their own capacity in these other areas.

2) GHOs should identify and exploit opportunities to engage UN human rights institutions.

The Framework Convention on Global Health and global health organizations

Incorporating GHO right to health stipulations into the FCGH

The FCGH elements that we have described should create new standards for GHOs. The FCGH would have to accommodate the diversity of GHOs. It might not be possible for all GHOs to adhere to all of the standards. A GHO with a small secretariat may not have the resources to justify a full-time human rights staff member, yet it might incorporate human rights functions into the job description of one of its staff. Resource and time constraints may impose further burdens, as implementing these measures will require developing and monitoring new policies and engaging additional partners. Yet even modestly sized GHOs can do much to advance the right to health. For example, the Global Health Workforce Alliance, with its primary functions of advocacy and generating knowledge, could integrate health workforce and right to health links. This could entail, for example, advising on how to incorporate human rights into national human resources strategies in relation to health worker education or equitable distribution of health workers, gathering and sharing best practices on these forms of integration, or convening meetings on the intersection of the health workforce and human rights.

As part of the FCGH, all state parties would agree to use their influence, as board members, funders, or otherwise, to ensure that GHOs adhere to the FCGH standards that are within the scope of the GHOs’ mission. The standards above might be supplemented by elements related to monitoring, reporting, and enforcement. These standards might also take the form of a “Code of Practice for Global Health Organizations and the Right to Health” that FCGH parties agree to support, possibly included as an annex to the FCGH. It might be possible for the FCGH to charge WHO with spearheading an effort to ensure that GHOs adhere to these standards if the FCGH is adopted through the World Health Assembly.

GHO certification and financing

To ensure adequate financing for GHOs, an overall FCGH financing framework on domestic and global health financing responsibilities could cover the financial requirements of GHOs. The FCGH secretariat, WHO, or another institution could certify GHO adherence to FCGH standards, making the GHO eligible to receive funds through pooled financing raised through the FCGH financing framework.

FCGH financing may be inadequate to cover GHO needs. Too few countries might agree to the framework, or financing demands might be too high. GHO financing might then be limited to a percentage of their needs, or certain GHOs might be prioritized for funding, based on alignment with FCGH principles and possibly other factors.

Global health organizations and collaboration towards and coherence for the right to health

FCGH signatories could commit to establishing a multi-sector, multi-stakeholder consortium to bring GHOs together around the right to health.40 This consortium could be designed to increase the voice of communities and civil society in these institutions.

The consortium could have four purposes: 1) improve coordination among GHOs, 2) create policy coherence by ensuring that non-health-centered global organizations and the regimes that they influence do not undermine and, wherever possible, actively promote, the right to health, 3) share lessons on promoting the right to health, and 4) elevate the role of civil society in ensuring that global institutions have a positive health impact, even if health is not their primary focus. One way in which the consortium might effectuate these purposes would be by developing recommendations for ways particular institutions can advance the right to health. The consortium could develop rules on how institutions should respond to these recommendations and have a process for monitoring their implementation.

Civil society and communities should have a significant role in governing the consortium. The consortium itself could have strict conflict of interest rules and standards for and possibly differentiated types of participation.

There are several options to run the consortium. It could potentially be led by WHO representatives. Alternatively, to capture the multi-sector nature of its membership, the consortium could be modeled to some extent on UNAIDS (an innovative partnership uniting 11 UN agencies), and housed in the United Nations as a new, collaborative agency. It would extend beyond the UNAIDS model to include entities not affiliated with the United Nations and have an enhanced, formal, decision-making role for civil society and communities. The consortium could be seen as a right to health analogue of UNAIDS, helping to promote, advocate for, and ensure accountability around the right to health among all global institutions. Whenever possible, the consortium should enable broad and inclusive participation, including through online and other social media forums.

Investing in health and human rights capacity building

The FCGH should establish a mechanism to enable significant funding for health and human rights capacity building. Funding could support a wide range of activities, primarily at local and national levels, to enhance the capacity of community and civil society organizations, government human rights institutions, the media, academic institutions, and think tanks to advance the right to health. Activities might include advancing the understanding of health-related human rights and how to claim them; advocating for health and human rights; deepening national and regional human rights networks; strengthening accountability mechanisms; and enhancing the capacity of marginalized populations to engage in health-related policy making, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation. The mechanism would help ensure that the right to health is integrated into national strategies and policies that GHOs support, and that the FCGH is being implemented effectively.

Financing should extend to stakeholders in all countries, though certain forms of funding (e.g., to government entities) may be limited to less wealthy countries. Even some of the world’s richest countries suffer severe right to health shortcomings, and solidarity among civil society organizations and networks across regions is critical to advancing human rights.

This financing might be raised through GHO commitments and policy changes, and by establishing a separate financing window for these purposes in new or reformed funding mechanisms that the FCGH could create or catalyze, such as a Global Fund for Health.41 The institutional home(s) for this financing would need to include broad ownership through governance structures, southern hemisphere leadership, and independent decision-making to mitigate the argument that foreign countries are seeking to impose their agendas by supporting civil society organizations. FCGH parties would need to commit to permitting funding to organizations in their home countries and avoid interfering with the civil society organizations.

Leadership on the FCGH

This paper has offered a series of recommendations that, if enshrined in a Framework Convention on Global Health, would enable major actors in global health to more effectively contribute to the right to health. Many leaders of such international, global health agencies are natural champions of the FCGH. The UNAIDS Executive Director recognizes the FCGH’s potential to protect and build upon the unprecedented gains and achievements of the international AIDS response, while bringing the same commitment to health and human rights and a principle of solidarity to the entirety of global health.42 We hope that other GHO leaders will reach the same conclusion, leverage their partnerships to engage stakeholders to encourage support for the FCGH, and demonstrate that in the world of global health, the overriding institutional interests of all GHOs—securing the right to health for all people—will be advanced by a Framework Convention on Global Health.

Eric A. Friedman, JD, is the Project Leader of the Joint Action and Learning Initiative on National and Global Responsibilities for Health (JALI) at the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at the Georgetown University Law Center in Washington, DC, USA.

Lawrence O. Gostin, JD, is University Professor of Global Health Law and Faculty Director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at the Georgetown University Law Center in Washington, DC, USA, and Director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Center on Public Health Law and Human Rights.

Kent Buse, PhD, is Chief, Political Affairs and Strategy at UNAIDS in Geneva, Switzerland.

Please address correspondence to the authors c/o Eric Friedman, O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, Georgetown University Law Center, 600 New Jersey Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20001, USA. Email: eaf74@law.georgetown.edu.

References

1. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI) (1966), art. 12. Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/cescr.htm.

2. G. Walt, K. Buse and A. Harmer, “Global cooperation in global public health.” In M.H. Merson, R.E. Black and A.J. Mills (eds.), International Public Health: Disease, Programs, Systems and Policies, 3rd ed. (Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett, 2011).

3. See, for example, L.O. Gostin, E.A. Friedman, G. Ooms et al., “The Joint Action and Learning Initiative: Towards a global agreement on national and global responsibilities for health,” PLoS Medicine 8/5 (2011). Available at http://www.plosmedicine.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.1001031. See also L.O. Gostin, “A Framework Convention on Global Health: Health for all, justice for all,” Journal of the American Medical Association 307/19 (2012), pp. 2087-92. Available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2072457.

4. E.A. Friedman and L.O. Gostin, “Pillars for progress on the right to health: Harnessing the potential of human rights through a Framework Convention on Global Health,” Health and Human Rights: An International Journal 14/1 (2012). Available at http://www.hhrjournal.org/index.php/hhr/article/view/483/740.

5. K. Buse and C. Naylor, “Commercial health governance.” In K. Buse, W. Hein and N. Drager (eds.), Making Sense of Global Health Governance: A policy perspective (Basingstoke, United Kingdom: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009); United Nations and UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations “protect, respect and remedy” Framework (New York and Geneva: United Nations, 2011). Available at http://www.hhrjournal.org/index.php/hhr/article/view/483/740; P. Hunt, The Right to Health: Note by the Secretary-General: Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, UN Doc. A/63/263 (August 11, 2008). Available at http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/human_rights/A63_263.pdf.

6. ICESCR (see note 1), art. 2; UN Charter, arts. 55-56.

7. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, UN Doc. No. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000), para. 11. Available at http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/gencomm/escgencom14.htm.

8. K. Buse and S. Tanaka, “Global Public-Private Health Partnerships: Lessons learned from ten years of experience.” International Dental Journal 61 (supple 2) (2012), pp. 2-10.

9. Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund), Board Members. Available at http://www.theglobalfund.org/en/board/members/.

10. UNAIDS, NGO/civil society participation in the PCB. Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/aboutunaids/unaidsprogrammecoordinatingboard/ngocivilsocietyparticipationinpcb/.

11. GAVI Alliance, GAVI Alliance Civil Society Constituency Charter (Geneva: GAVI Alliance, 2010). Available at http://gavicso.org/pdf/GAVI%20CSO%20Charter.pdf.

12. Human Rights Council, G.A. Res. 60/251, U.N. Doc. A/60/L48 (March 15, 2006). Available at http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/hrc60-251.html.

13. Global Fund, The Global Fund’s Strategy for Ensuring Gender Equality in the Response to HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Geneva: Global Fund, 2008). Available at http://www.theglobalfund.org/en/civilsociety/reports/. Global Fund, The Global Fund Strategy in Relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identities (Geneva: Global Fund, 2009). Available at http://www.theglobalfund.org/en/civilsociety/reports/.

14. Constitution of the World Health Organization (1946), preamble. Available at http://apps.who.int/gb/bd/PDF/bd47/EN/constitution-en.pdf.

15. Global Fund, The Global Fund Strategy 2012-2016: Investing for Impact (Geneva: Global Fund, 2012), pp. 17-18. Available at http://www.theglobalfund.org/documents/core/strategies/Core_GlobalFund_Strategy_en/.

16. Global Fund, Board Action on the Right to Travel of People Living with HIV, 16th Board meeting (November 12-13, 2007), GF/B16/DP24. Available at http://www.theglobalfund.org/documents/board/16/BM16_BoardMeeting_Decisions_en/.

17. UNAIDS, Young people present first-ever ‘crowdsourced’ recommendations for AIDS response in UN history (April 24, 2012). Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/pressreleaseandstatementarchive/2012/april/20120424prcrowdoutaids/.

18. Global Health Workforce Alliance, Moving Forward from Kampala (Geneva: Global Health Workforce Alliance, 2009), p. 9. Available at http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/moving_forward/en/index.html.

19. D.B. Evans, P. Saksena, R. Elovainio and T. Boerma, Measuring Progress towards Universal Coverage: Background Paper for the Meeting on Universal Health Coverage at the Rockefeller Foundation Center, Bellagio, September 17-21, 2012 (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012), pp. 7, 9.

20. Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and UNAIDS, International Guidelines on HIV/AIDS and Human Rights, 2006 Consolidated Version (Geneva: UNAIDS, 2006). Available at http://data.unaids.org/Publications/IRC-pub07/jc1252-internguidelines_en.pdf; Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS, U.N. Doc. A/RES/S-26/2 (June 27, 2001). Available at http://www.un.org/ga/aids/docs/aress262.pdf; Political Declaration on HIV/AIDS, U.N. Doc. A/RES/60/262 (June 2, 2006). Available at http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2006/20060615_hlm_politicaldeclaration_ares60262_en.pdf. Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS: Intensifying Our Efforts to Eliminate HIV and AIDS, U.N. Doc. A/RES/65/277 (June 10, 2011) (Political Declaration 2011). Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/document/2011/06/20110610_UN_A-RES-65-277_en.pdf.

21. UNAIDS, “UNAIDS expresses serious concern over ruling in Malawi,” May 20, 2010. Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/pressreleaseandstatementarchive/2010/may/20100520psmalawi/.

22. T. Lin, “A Charm Offensive Against AIDS,” New York Times, February 21, 2012. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/21/science/charm-offensive-is-unaids-chiefs-strategy.html.

23. New York Times, “China to Relax Ban on Foreigners with HIV,” New York Times, November 13, 2007. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/13/world/asia/13iht-china.1.8310072.html. See also S. Juan, “Ban removed on foreigners with HIV,” China Daily, April 29, 2010. Available at http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2010-04/29/content_9788598.htm.

24. UNAIDS, Making the Law Work for the HIV Response (Geneva: UNAIDS, 2010). Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/priorities/20100728_HR_Poster_en.pdf.

25. UNAIDS, Global AIDS Response Progress Reporting 2012 (Geneva: UNAIDS, 2011), p. 15. Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/document/2011/JC2215_Global_AIDS_Response_Progress_Reporting_en.pdf.

26. Political Declaration 2011 (see note 20), para. 102.

27. World Health Organization (WHO), 25 Questions and Answers on Health and Human Rights (Geneva: WHO, 2002). Available at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42526/1/9241545690.pdf; WHO, Human Rights and Gender Equality in Health Sector Strategies: How to Assess Policy Coherence (Geneva: WHO, 2011). Available at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44438/1/9789241564083_eng.pdf; WHO, Other Guidelines and Publications Relevant to Human Rights. Available at http://www.who.int/hhr/information/guidelines_publications/en/index.html.

28. Global Fund, Tuberculosis and Human Rights Information Note (Geneva: Global Fund, 2011). Available at http://www.theglobalfund.org/documents/rounds/11/R11_TB-HumanRights_InfoNote_en; Global Fund, HIV and Human Rights Information Note (Geneva: Global Fund, 2011). Available at http://www.theglobalfund.org/documents/rounds/11/R11_HIVHumanRights_Infonote_en/; Global Fund, Matching Resources to Need: Opportunities to Promote Equity Information Note (Geneva: Global Fund, 2011). Available at http://www.theglobalfund.org/documents/monitoring_evaluation/ME_Equity_Guidance_en/.

29. Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and World Health Organization, 50th Directing Council, Resolution CD50.R8 Health and Human Rights (Washington, DC: PAHO, 2010). Available at http://new.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2010/CD50.R8-e.pdf.; UNAIDS, Courting Rights: Case Studies in Litigating the Human Rights of People Living with HIV (Geneva: UNAIDS, 2006). Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/dataimport/pub/report/2006/jc1189-courtingrights_en.pdf.; UNAIDS, HIV-Related Stigma, Discrimination and Human Rights Violations: Case studies of successful programmes (Geneva: UNAIDS, 2005). Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/dataimport/publications/irc-pub06/jc999-humrightsviol_en.pdf.

30. International Health Partnership and Related Initiatives (IHP+), Joint Assessment of National Health Strategies (JANS) Tool & Guidelines. Available at http://www.internationalhealthpartnership.net/en/tools/jans-tool-and-guidelines/.

31. International HIV/AIDS Alliance and the Global Fund, Civil Society Success on the Ground: Community systems strengthening and dual-track financing: Nine illustrative case studies (Brighton, United Kingdom and Geneva, Switzerland: International HIV/AIDS Alliance and Global Fund, 2008), p. 6. Available at http://www.theglobalfund.org/documents/civil_society/CivilSociety_CSSAndDualTrackFinancing_CaseStudy_en/.

32. Health Policy Action Fund, The Health Policy Action Fund. Available at http://www.healthpolicyactionfund.org/.

33. Global Fund, Evolving the Funding Model (Part 2), 28th Board meeting (November 14-15, 2012), GF/B28/DP4. Available at http://www.theglobalfund.org/documents/board/28/BM28_DecisionPoints_Report_en/.

34. Global Fund, Policy on Eligibility Criteria, Counterpart Financing Requirements, and Parioritization of Proposals for Funding from the Global Fund, 23rd Board meeting (May 11-12, 2011), GF/B23/14, Attachment 1. Available at http://www.theglobalfund.org/documents/board/23/BM23_14PICPSCJEligibilityAttachment1_Policy_en/.

35. M.G. Marmot, et al. Fair Society, Healthy Lives: Strategic review of health inequalities in England post-2010 (London: The Marmot Review, 2010), p. 16. Available at http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/projects/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review/fair-society-healthy-lives-full-report.

36. Cambodia Country Coordinating Mechanism, Round 9 proposal (2009), pp. 58-60. See also E. A. Friedman, Guide to Using Round 10 of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria to Support Health Systems Strengthening (Washington, DC and Cambridge, MA: Physicians for Human Rights, 2010), p. 12. Available at https://s3.amazonaws.com/PHR_other/round10-gf-hss-guide.pdf.

37. See Global Fund, The Global Fund’s strategy for ensuring gender equality in the response to HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria (Geneva: Global Fund, 2008). Available at http://www.theglobalfund.org/en/civilsociety/reports/; Global Fund, The Global Fund Strategy in Relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identities (Geneva: Global Fund, 2009). Available at http://www.theglobalfund.org/en/civilsociety/reports/.

38. Global Fund, Other Guidance. Available at http://www.theglobalfund.org/en/application/otherguidance/; Global Fund, Matching Resources to Need: Opportunities to promote equity information Note (Geneva: Global Fund, 2011), p. 2. Available at http://www.theglobalfund.org/documents/monitoring_evaluation/ME_Equity_Guidance_en/.

39. UNAIDS, WHO and UNDP, Using TRIPS Flexibilities to Improve Access to HIV Treatment (Geneva: UNAIDS, 2011). Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/JC2049_PolicyBrief_TRIPS_en.pdf.

40. Gostin (see note 3).

41. G. Cometto, G. Ooms, A. Starrs and P. Zeitz, “A global fund for the health MDGs?” Lancet 373/9674 (2010), pp. 1500-1502.

42. M. Sidibé and K. Buse, “A framework convention on global health: a catalyst for health justice,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 90/12 (2012), pp. 870-870A. Available at http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/90/12/12-114371.pdf.