Siân Oram, Cathy Zimmerman, Brad Adams, and Joanna Busza

Health and Human Rights 13/2

Published December 2011

Abstract

Background

Human trafficking has been recognized both by the international community and many individual states around the world as a serious violation of human rights. Trafficking is associated with extreme violence and a range of physical, mental, and sexual health consequences. Despite the extreme nature of the harm caused by human trafficking, harm is not a concept that is integrated in the definition of trafficking or in policies to address the health of trafficked people. This paper examines the United Kingdom’s response to human trafficking as a case study to explore national policy responses to the health needs of trafficked people and assess the willingness of UK authorities to implement international and regional law in securing trafficked people’s health rights.

Methods

Between 2007 and 2010, data on the development of the UK response to trafficking were obtained through 46 interviews with key trafficking policy stakeholders and health care providers, participant observation at 41 policy-relevant events, and document collection. Framework analysis was used to analyze the data.

Results

International and regional instruments specifically protect the health rights of trafficked people. Yet, UK engagement with trafficked people’s health rights has been limited to granting, under certain circumstances, free access to health care services. Changes to trafficked people’s entitlements to free health care occurred following the ratification of the Council of Europe Convention on Action Against Trafficking in Human Beings, but had limited impact on trafficked people’s access to medical care.

Conclusions

International and regional instruments that provide specific or mandated instruction about states’ health care obligations can be effective in furthering the health rights of vulnerable migrant groups. The UK government has demonstrated limited appetite for exceeding its minimum obligations to provide for the health of trafficked people, however, and key principles for promoting the health rights of trafficked people are yet to be fulfilled.

Introduction

Human trafficking has been recognized as a serious violation of human rights by the international community and many nations around the world.1 Given the extreme nature of acts frequently involved in trafficking, including violence, coercion, confinement, and exploitation, human trafficking has made it to the top of the agenda for many rights groups and international organizations. According to the definition established in the principle international instrument on human trafficking, the United Nations Optional Protocol on the Prevention, Suppression and Punishment of Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (the “Palermo Protocol”), human trafficking is a crime that involves the movement of persons, typically by force, deception or abuse of vulnerability, for the purposes of exploitation.2 People may be trafficked into forced prostitution and into forced labor in industries as diverse as agriculture, construction, and domestic servitude, and for begging and forced marriage.3

Although international and regional instruments and various pieces of national legislation have described legal rights and remedies for trafficked persons, the subjects of “harm” and the “health rights” of trafficked persons have received woefully little attention. Indeed, the Palermo Protocol’s definition of “human trafficking” does not explicitly recognize “harm” or the potential for harm as a fundamental component of trafficking—unlike, for example, the UN Convention on Torture or the UN Declaration on Violence Against Women, which explicitly recognize harm as a consequence of these violations.4 The Palermo Protocol encourages but does not require states to respond to the health needs of trafficking victims. Article 6, subsection (3) states:

Each State Party shall consider implementing measures to provide for the physical, psychological and social recovery of victims of trafficking in persons…in particular, the provision of:

(a) Medical, psychological and material assistance5

Despite the weak language (“shall consider”) and the limited breadth of the instruction, this document does for the first time recognize that states should address the health consequences of trafficking. The absence of more defined standards within this and other instruments, such as the 2005 Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (ECAT), however, raises questions about how governments will choose to implement health policies and services for trafficked people.6

The small body of research on health and trafficking is dominated by studies on trafficking for sexual exploitation and focuses on trafficking in South Asia and, to a lesser extent, Europe.7 Although the populations included in these studies cannot be considered representative of trafficked people, research suggests that the trafficking of women for sexual exploitation is associated with extreme levels of violence and a range of poor health consequences. A multi-country study of 192 women trafficked in Europe, for example, found that 94.8% reported having experienced violence while trafficked; this level is comparable with some of the highest recorded rates of gender-based violence in the world.8 Other studies have reported that many sex-trafficked women suffer from depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder and, in some settings, are at significant risk of HIV infection and other sexually transmitted infections.9 Literature on the health outcomes associated with trafficking for labour exploitation and on the specific health needs of trafficked children and trafficked men remains scarce. A small number of studies and reports have, however, documented substantial levels of psychological abuse and physical violence and indicated that survivors may present with an array of poor physical and mental health outcomes.10

In this paper, we offer an analysis of trafficked people’s right to health as mandated by international and European Union (EU) law and, using the United Kingdom’s response to human trafficking as a case study, we discuss the effectiveness (or lack thereof) of these laws in securing trafficked people’s access to health care. Due to the near-absence of research-based evidence on the health needs of trafficked children, the limited changes in policies on trafficked children’s health rights during the study period, and the different and specialized health and social care arrangements required for unaccompanied minors, this paper focuses on the health rights of trafficked adults. Although discourses on human trafficking have been dominated by the trafficking of women for sexual exploitation, these study findings are also relevant for trafficked men and people trafficked to the UK for labor exploitation.

Methods

Qualitative methods were used to explore the extent to which health was incorporated into the UK response to human trafficking between 2000 and 2010. Data were collected using in-depth interviews, participant observation, and document collection. Ethical approval for the research was provided by the ethics committees of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the National Health Service (NHS) National Research Ethics Service.

Sampling for the interviews relied on a combination of purposive and snowball methods. Forty-six interviews were conducted with representatives of 43 organizations, including civil servants (n=7); NGO post-trafficking support providers (n=7); NGO anti-trafficking advocates (n=10); and lawyers (n=5), enforcement officials (n=7) and health care providers (n=7) with expertise in human trafficking. As the research focused on the development of the UK policy and service responses to trafficking, and because trafficked people were not active participants in the development of these responses, no interviews were conducted with trafficked people. All participants provided informed written consent to take part in interviews, 41 of which were digitally recorded and transcribed. Forty-three interviews were conducted between January and September 2009, coinciding with the entry into force in the UK of ECAT. Three follow-up interviews were conducted with service providers a year after ECAT entered into force.

Data were also collected during participant observation at 41 policy-relevant meetings and events between September 2007 and July 2010. Detailed field notes were made during these events and anonymized during transcription. Finally, policy-related documents, such as government consultations, inquiry testimonies, impact assessments, meeting minutes and NGO reports and materials, were collected and analyzed. This analysis provides both the context and a supplementary source of data to understand UK policymaking.

Data analysis was conducted in NVivo 8 and Microsoft Excel and followed the principles of framework analysis.11 A conceptual framework of policy change based on Kingdon’s Three Streams Model provided the basis for thematic analysis and was developed further as analysis progressed.12

Results

International and regional legal instruments to protect the health of trafficked people

The rights of people trafficked to or within the UK are governed by international law (including law deriving from Council of Europe treaties), European Union law, and domestic law. Table 1 lists the key international and regional instruments relevant to trafficked people’s health rights.

Table 1: International and regional legal instruments governing the health rights of trafficked adults

|

Category |

Instrument Name |

|

International |

• International Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) • Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) • International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (the UN Migrant Workers Convention) •United Nations Optional Protocol on the Prevention, Suppression and Punishment of Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (the Palermo Protocol) |

|

Council of Europe |

• European Social Charter • Council of Europe Convention on Action Against Trafficking in Human Beings (ECAT) |

|

European Union |

• Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union • Directive 2004/81/EC on the Residence Permit Issued to Third Country Nationals Who Are Victims of Trafficking in Human Beings, or Who Have Been the Subject of an Action to Facilitate Illegal Immigration, Who Cooperate With the Competent Authorities. • Directive 2011/36/EU on Preventing and Combating Trafficking in Human Beings and Protecting its Victims |

The UK is signatory to a number of international and EU legal instruments that do not refer specifically to trafficked people but which provide, in general terms, for their health rights. The International Convention on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the European Social Charter (ESC) and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (“Charter of Fundamental Rights”), for example, underline the general health rights of all persons regardless of residence status.13 General Comment 20 (2009) to the ICESCR also specifically names trafficked people as a group to whom the Covenant rights apply.14 The Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) requires states to take appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in the field of health care and to ensure equality of access to health care services.15 In particular, CEDAW, and General Recommendation 24 of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, requires states to ensure appropriate services during pregnancy and the post-natal period and provide for free services where necessary.16 The UN Migrant Workers Convention recognizes the rights of migrant populations and their families to health care and other protections, but has not been signed by the UK.17

The UK has also signed and ratified two international legal instruments which are specific to trafficking: the Palermo Protocol and ECAT.18 These instruments each recognize the health consequences of trafficking and make limited requirements for States to provide health care to trafficked people.

The Palermo Protocol was introduced primarily as a vehicle to mandate states to investigate and prosecute cases of human trafficking, and thus included very few requirments for the support and protection of victims of trafficking. As noted in the introduction, the Palermo Protocol encourages governments to provide “medical, psychological, and material assistance” to trafficked people, but does not guarantee trafficked people’s right to health care in the UK.19 ECAT imposed duties on states to provide health care for trafficked people, but in a context in which there were significant variations across states’ existing health care provisions, the prescribed standard remained low. ECAT requires that governments provide “emergency medical treatment” to all persons who are suspected of, or formally identified as, having been trafficked and that necessary but non-emergency medical treatment is provided to “victims [who are] lawfully resident within [a signatory State’s] territory who do not have adequate resources and need such help.”20 Despite going further than the Palermo Protocol in providing for the health of trafficked people, ECAT does not give all trafficked people a right to comprehensive health care.

The UK opted out of the Directive 2004/81 on the Residence Permit Issued to Third Country Nationals who are Victims of Trafficking in Human Beings, which would have required the provision of medical treatment and psychological care to trafficked people under certain conditions.21 More recently, however, the UK has announced its intention to opt into EU Framework Directive 2011/36 on human trafficking (“the Directive”) and has until April 2013 to transpose the directive into its domestic law.22 The Directive requires states to provide “necessary medical treatment [and] psychological assistance” to trafficked people. It further requires States to “attend to victims with special needs, where those needs derive, in particular, from whether they are pregnant, their health, a disability, a mental or psychological disorder they have, or a serious form of psychological, physical or sexual violence they have suffered.” The Directive goes further than ECAT in requiring states to meet the health needs of trafficked people and its transposition into English law should introduce domestically enforceable rights for trafficked people.23 Following the transposition period, trafficked people may also be able to seek to enforce their rights under the Directive itself (where its provisions are considered to be directly effective).

Both ECAT and the Directive require states to establish procedures for the identification and provision of appropriate support to trafficked people. Many countries have established “National Referral Mechanisms” (NRMs) to address these requirements. The NRM was envisioned by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) as a “cooperative framework through which state actors … ensure that the human rights of trafficked persons are respected and provide an effective way to refer victims of trafficking to services.”24 Over the past five years, the NRM has become an important best-practice component of European and Eurasian responses to trafficking.25

UK provisions to safeguard trafficked people’s right to health in response to its international obligations

Analysis of domestic anti-trafficking laws, immigration law, health care regulations and government documents relating to the response to human trafficking suggests that the UK did not put laws or policies in place to meet their obligations towards trafficked people’s right to health under the ICESCR, ESC, or Charter of Fundamental Rights during the period of interest.

In the UK, a person is entitled to free health care through the National Health Service (NHS) if they are “ordinarily” residing in the UK. Ordinary residence is a common law concept, the established meaning of which is that a person is ordinarily residing in the UK, apart from temporary or occasional absences, and that their residence has been adopted voluntarily for settled purposes as part of the regular order of their life for the time being. The NHS (Charges to Overseas Visitors) Regulations 1989 (the “NHS Charging Regulations”) also grant exemptions from charges for specified categories of visitor (including asylum seekers, refugees, EU citizens with the right to reside in the UK, and people who have been living lawfully in the UK for the preceding 12 months). The NHS Charging Regulations exempt particular categories of illness or treatment from charges, including services provided in Accident and Emergency departments, sexual health care, family planning services, compulsory psychiatric treatment and treatment for specified infectious diseases (e.g. tuberculosis). General Practitioners (GPs) have discretion to offer free primary care to all people and are required to treat anyone in immediate need. Overseas visitors who are referred for secondary care by their GP are not, however, automatically entitled to free hospital treatment beyond the basic provision detailed above.26

Until 2009, the NHS Charging Regulations did not specifically exempt trafficked people from charges for health care.27 The regulations meant although certain trafficked people were entitled to receive free health care (including asylum seekers and refugees and EU citizens with the right to reside in the UK), others, (including refused asylum seekers, EU citizens with no right to reside in the UK, and non-EU citizens who were unlawfully in the UK and had not claimed asylum) were only entitled to access a limited range of services at no charge.28 Trafficked people in the latter groups would therefore be charged for a range of services that they were likely to need, including maternity care, termination of pregnancy, and HIV treatment.

The Palermo Protocol was signed by the UK in 2000 and ratified in 2006. This research, however, indicated that neither the signing nor ratification of this instrument prompted changes in UK provision for trafficked people’s right to health. It was only with the ratification of ECAT that the UK made changes to trafficked people’s entitlements to access free health care services.

In 2008, the NHS Charging Regulations were amended to exempt from payment persons “who the competent authorities of the United Kingdom for the purposes of the Council of Europe Convention on Action Against Trafficking in Human Beings” considered to have been trafficked.29 In contrast to other aspects of the implementation of ECAT, such as the length of “reflection and recovery periods” and residence permits, consultation and non-governmental input into the changes to the NHS Charging Regulations were minimal. According to an NGO advocate, “The call for health care has not been at the center of what we’ve been asking for because there were a few other things that we were focusing on…a better system of identification, a reflection period of three months, non-criminalization [of trafficked people for immigration offences], and residence permits.”30

The changes to the NHS Charging Regulations were made specifically in response to the government’s requirements under ECAT. A document that analyzed the requirements and projected impact of ratification, for example, acknowledged the requirement for identified trafficked people to be able to access “Convention-compliant support” and stated that the government would therefore introduce “legislation to exempt non-UK national victims of human trafficking from being charged for ‘emergency’ health care.”31 Similarly, a civil servant who was interviewed commented, “It wasn’t clear whether our existing provisions would have allowed all the access that the Convention required…and [so] we drafted amendments to the secondary legislation.”

The UK had, however, always provided Accident and Emergency department care to overseas nationals without charge. Another civil servant argued, therefore, that as a result of the amendment to the NHS Charging Regulations, the UK had gone beyond its requirements under ECAT. Yet, another civil servant, who had worked on the amendment to the charging regulations, stated, “I’m not sure that we really have gone beyond the minimum requirements…what we were trying to do was make sure there wasn’t a grey area…you know, our intention was exactly as the Convention described.”

A third civil servant, who had also worked on drafting the amendment, explained how the decision to exempt trafficked people from charges from all medical care had been taken firstly because of the lack of clarity about what constituted “emergency medical treatment.” The explanatory report to ECAT did not define what was to be included under the heading of “emergency medical care.”32 Most civil servants who were interviewed reported that they, in conjunction with government lawyers, had decided that emergency medical treatment mandated by ECAT was not limited to care received within Accident and Emergency departments and should also include other in-patient care.33

The form that the exemption could take was reportedly constrained by the pre-existence of the NHS Charging Regulations, which were constructed so that groups of overseas nationals were either charged for all but a basic array of services or exempt from all charges. Civil servants described how, in this context, an amendment that exempted trafficked people from charges for medical services was “more straightforward” than developing a set of intermediate entitlements. Furthermore, ECAT required not only that “emergency medical treatment” be provided to all people suspected of having been trafficked, but also that further “necessary treatment” be provided to victims who were lawfully resident in the UK. The NHS Charging Regulations only exempted, however, visitors who had been lawfully resident in the UK for a year or more. Civil servants were therefore required to draft the amendment in such as way that trafficked people who had been lawfully resident in the UK for less than a year would be entitled to necessary medical care.

Yet the amendment was constructed so that trafficked people were only entitled to free medical care if they had been officially identified as likely victims of trafficking and granted temporary admission on this basis. While seeking to comply with the terms of ECAT regarding the provision of health care to trafficked people, it appeared that the UK did not seek to exceed its minimum obligations.

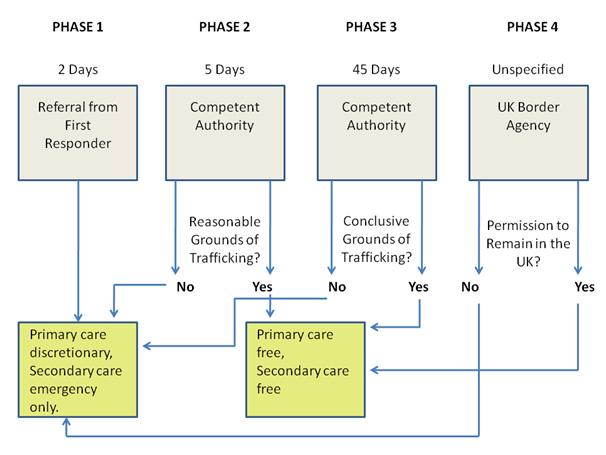

In order to be officially identified as a victim of trafficking, a person had to enter into the UK National Referral Mechanism (NRM).34 The NRM was introduced in the UK in April 2009 as a means of implementing other requirements of ECAT in relation to the identification of victims and provision of temporary immigration protection for trafficked people. People who are suspected of having been trafficked may be referred into the NRM by named “First Responder” agencies (such as the police, immigration officials, and a small number of NGOs). “Competent Authority” caseworkers then make a preliminary decision on whether there are “reasonable grounds” to believe that a person had been trafficked. A positive decision at this stage grants the person a 45-day (extendable) “recovery and reflection” period, during which time they can access support and no action can be taken to remove them from the UK. A more rigorous assessment of whether the person is “on the balance of probabilities” believed to be trafficked is also conducted during the 45-day period. A positive decision at this stage enables the person to apply for a one-year residency permit either to assist with a criminal investigation or on humanitarian grounds, during which time they can continue to access support. There is no right of appeal at any stage in the event of a negative decision.

Figure 1 illustrates the referral and decision making processes of the NRM and the associated health care entitlements.

Prior to being referred into the NRM, a person who is suspected of having been trafficked has no entitlement to free health care on the basis that they may have been trafficked (although they may be eligible on other grounds, for example, because they have claimed asylum or are EU nationals with the right to reside in the UK). Furthermore, referral into the NRM (Phase 1) does not exempt a suspected trafficked person from health care charges. A positive “reasonable grounds” decision (Phase 2) entitles the suspected trafficked person to free primary and secondary NHS health care for 45 days. This decision is meant to be made within five working days of a referral. Following this 45-day period, a “conclusive grounds” decision is made (Phase 3). If this decision is positive and if the trafficked person is subsequently granted a temporary residence permit (Phase 4), they can continue to access free primary and secondary health care through the NHS. If a person chose not to enter into the NRM, or if their claim to be trafficked was rejected, they are not entitled to receive free care beyond the basic medical services available to all.

While the NRM was originally envisioned as a referral system to meet trafficking survivors’ various support and protection needs, in the UK, the NRM has been implemented primarily as a means for identifying trafficked people and granting temporary admission in the form of “reflection and recovery periods” and residence permits. In fact, although a person’s entry into the UK NRM is necessary in order for them to become eligible for health care and other forms of support, the UK NRM does not coordinate the provision of support or ensure that support is provided.

Currently, there is no mechanism in the UK for ensuring that trafficked people are offered health assessments and forensic examinations for criminal or civil actions, or that trafficked people are provided with the health care they may need. Moreover, the changes to trafficked people’s entitlements to free medical care have not been accompanied by awareness-raising or training in the health sector.

The changes to health rights in the UK made in response to ECAT have had little impact on trafficked people’s access to health care

During interviews with non-governmental stakeholders, most were critical of the amended NHS Charging Regulations, claiming that tying health care access to a person’s identification through the NRM was highly problematic. Lawyers, support providers and NGO advocates explained that, because entry into the NRM alerted the immigration authorities to a person’s presence in the country and the mechanism did not include an appeals process, many people whom they believed to have been trafficked decided not to be referred. According to one NGO advocate, “You get everything free. I mean that’s great, but really, how many people are going through the NRM? If you’re not accepted then you would be removed much quicker than you necessarily would have been.” As Figure 1 illustrates, trafficked people who chose not to enter into the NRM and who did not qualify for free health care on other grounds (for example, because they had claimed or been granted asylum), could be charged for medical care.

Non-governmental stakeholders were also critical of the potential for the NRM to delay people’s access to health care. According to one lawyer, “Health care interventions are needed fairly early on – having to wait for [NRM] assessments to be undertaken and [approval] letters to be sent out means delays in care.”

The initial “reasonable grounds” decisions that give access to free health care are meant to be issued within five working days of a referral, but support providers reported that these targets were often missed. During interviews conducted in mid-2010, two service providers reported that their clients were waiting an average of 40 and 70 days for decisions.

Lawyers, support providers and NGO advocates also believed that poor decision making and the lack of an appeals system limited the amendment’s potential for ensuring trafficked people’s access to the health care they needed. One lawyer said, “The amendment has made no difference at all, because people aren’t being recognized as trafficked. Getting the [NRM] letter, getting the recognition that a person has been trafficked is problematic.”

Table 2 shows the proportion of applications refused at the reasonable and conclusive grounds stages. Of the 1,091 applications made by adults to the NRM between April 2009 and March 2011, two-fifths were granted a positive reasonable grounds decision and a third had been refused. Five hundred and six applications pertained to trafficking for sexual exploitation, 331 to labor exploitation, and 201 to domestic servitude. Of the 635 who had received a conclusive grounds decision, over half had received a positive decision and approximately one-quarter had been refused.35 Positive conclusive grounds decisions were received by 27.4% of applicants who claimed to have been trafficked for sexual exploitation, 50.4% of labor exploitation claimants, and 23.4% of domestic servitude claimants.36

Table 2: Outcomes of applications to the UK National Referral Mechanism for the period April 2009-March 2011

|

Outcome |

Reasonable Grounds (%)(n=1,091) |

Conclusive Grounds (%)(n=635) |

|

Accepted |

58.2 |

56.1 |

|

Refused |

33.8 |

24.6 |

|

Pending |

3.7 |

15.4 |

|

Other* |

4.3 |

3.9 |

* “Other” includes applications that have been suspended or withdrawn.

Even though medical care was available for people officially identified as having been trafficked via the NRM, access was not necessarily smooth. The lack of a clear and well-linked referral system and poor awareness among health care providers and administrators about the amendment to the NHS Charging Regulations meant that support providers often had to intervene to assure providers that individuals were entitled to care. According to a service provider, “There have been occasions where [trafficked people] haven’t taken their NRM letters and they’ve still been able to access [health care]. Or sometimes they’ve been questioned and we’ve confirmed that they are under the NRM as a victim of trafficking. And the [health staff] may well have absolutely no knowledge at all about what we’re talking about.”

In practice, although the ratification of ECAT triggered a modest domestic legal change in trafficked people’s right to health care, the UK government did not appear to invest time or resources into implementing operational mechanisms to ensure that trafficked people would be able to access health care services as part of the NRM.

Trafficked persons are likely to find it extremely difficult to access health services on their own, without support from local advocates or caseworkers. Interviewees reported that health care providers’ insistence on proof of address, and in some cases immigration status, was a particular barrier to trafficked people’s access. According to one of the service providers, “When we [first] took service users to register with a GP, for instance, it was ‘No, you haven’t got this, you haven’t got that, how long have you been in the country? Can you give us your old address?’ and all of these things that they would ask for, which obviously women could not provide. So they could not register with GPs. In some cases they could not even register with emergency appointments.”

Service providers also discussed trafficked people’s difficulties in navigating an unfamiliar health care system, arranging for interpreters to attend appointments, and accessing information about services and medication in a suitable language and format.

Despite the lack of a more organized system to ensure health care for trafficking survivors, at the service level, some support providers were able to facilitate their clients’ access to health services. NGO interviewees described how the NHS Charging Regulations were inconsistently implemented. Accordingly, the ease with which trafficked people were able to access services varied by area and by service type. According to an NGO, “A large number of the trafficked people that we’ve seen have actually been from a borough for which it’s quite easy to get someone access. But every so often, we will see trafficked people from other boroughs, and it becomes a lot more difficult.”

Furthermore, some support providers explained that, independent of the NRM or Department of Health and without government dedicated support, they had proactively trained and developed relationships with local primary care and sexual health clinics in order to help their clients to access health care: “What we have done…is set up agreements with sexual health services and also with the GPs around the areas where we house women…making those personal links. Saying, ‘here’s our number, do call us’…I mean, a lot of it is training and information sharing.”

In addition, to ensure passage through health service ‘gatekeepers,’ (for example, receptionists) support workers often accompanied their clients to register for services and at appointments. Support providers suggested that their clients continued to encounter difficulties accessing mental health services, but that in the majority of cases building local relationships with health care providers and accompanying their clients to appointments had yielded positive results.

Discussion

As one of the only case studies on the health policies associated with human trafficking, our findings suggest, first, that general international obligations to respect, protect, and fulfill the health rights of all persons (such as those found in the ICESCR) are likely to be insufficient to ensure that especially vulnerable and marginal groups have meaningful access to the health care services they are likely to need. Although the UK was bound by a number of legal instruments to provide for the health rights of people in its territory, and despite a general comment to the ICESCR specifically listing trafficked people as a group to whom the right to non-discrimination applied, it was not until ECAT entered into force that people had a right to health care on the grounds that they had been trafficked.

It appears that if international standards do not provide sufficiently specific or mandated instruction about states’ medical and health care obligations, and if dedicated advocacy for health rights is lacking, the UK is not likely to legislate voluntarily for full access to care for these non-resident groups. When mandated by ECAT to provide medical care for trafficked people, the UK government amended its legislation to meet its obligations. Our results indicate, however, that the government did not seek to exceed the minimum standards laid down by ECAT and, furthermore, that it did not integrate the provision of health care into identification and referral procedures.

In 2009, the UK formally instituted an NRM, which, by definition, should have put into place mechanisms to ensure efficient referral to health services. The UK NRM has, in practice, not operated this way and in some ways it has actually created new hurdles to care. By requiring trafficked people to enter into the NRM in order to be eligible for free health care, the amendment to the NHS Charging Regulations risks delaying access to free medical care and maintains the link between access and trafficked people’s immigration status. The entitlement to free health care services is more stringent for trafficked people than for other vulnerable migrants, such as asylum seekers. Whereas asylum seekers receive exemptions from health care charges upon registering their claim, trafficked people must wait to be recognized via the NRM before becoming entitled to free care. Research into trafficked people’s self-reported health symptoms suggests, however, that it is in the days immediately after leaving the situation of exploitation that the need for health care is greatest.37

During the study period, the UK NRM procedures functioned primarily as identification and immigration tools and made extraordinarily little provision for the coordination of support and assistance. Despite tying trafficked people’s entitlement to health care to their progress through the NRM, the mechanism still does not include procedures to offer health assessments or health care to trafficked people, and does not provide assistance with health care referrals. Pockets of good practice do exist, however, in the UK. The Helen Bamber Foundation and Freedom from Torture, for example, are charities that provide therapeutic support for trafficked people and other victims of abuse. The independent activities of post-trafficking service providers have also fostered the development of informal local health care networks that are capable of supporting trafficked people. Nonetheless, trafficked people may continue to find it difficult to access the medical care they need, particularly if they are not in the care of NGO service providers.38

Findings from this UK case study suggest that entry into a NRM should, at a minimum, prompt the offer of a health assessment and assistance through referral to health care services, as needed. In particular, trafficked people may require help registering with services; booking appointments; arranging for interpretation and translation services; paying for prescriptions and applying for exemptions from prescription charges; and gaining written medical information in an appropriate language and format. As part of the process of ensuring health care for trafficking survivors, governments should provide awareness-raising and training for health care practitioners.39

The transposition of Directive 2011/36 in the UK and elsewhere in Europe provides an opportunity to address these issues over the next two years. To date, the health sector has not engaged with dialogues about the provision of support for trafficked people or trafficked people’s rights to health care. The EU has encouraged governments to publish their plans for transposing the Directive, and health and human rights advocates should participate in the development, implementation, and monitoring of these plans.40 States’ obligation not to “adopt measures that may seriously compromise the attainment of the result prescribed by the Directive” will be an important advocacy position during the transposition period.41 The Directive also provides a firmer basis for the elaboration of trafficked people’s health rights. It not only requires that States provide “necessary medical treatment,” but also that they attend to broader needs that arise as a result of trafficked people’s health.42

Although the right to medical care is a major component of the right to health, there is now a need to go beyond issues of health care access to additionally consider the broader impact of the response to trafficking on people’s physical, psychological, and social well-being. For example, while studies of asylum seekers and refugees tend to emphasise the impact of past events on mental health rather than post-migration experiences, a small number of studies indicate that experiences in the host country are likely to exacerbate existing health problems and foster new health complications. Like asylum seekers and refugees, trafficking survivors may be negatively affected by, for example, experiences of poverty, poor social support, and racial discrimination in the destination country.43 Trafficked people’s mental health may also be affected by a range of socio-legal stressors, including: delays in processing applications; interviews and conflict with immigration officials and fears of repatriation; the denial of work permits; unemployment; dependency; financial difficulties; separation from families; poor social support, loneliness and boredom; and discrimination.44

Government documents frequently describe the UK response to human trafficking as “victim-centered” but, to date, no systematic analysis has been undertaken of the extent to which the UK response to trafficking meets the health needs of trafficked people or whether aspects of the response negatively impact upon trafficked people’s health.45 Health policies and service access for trafficking survivors requires greater scrutiny — and urgently. If the UK and other countries declaring their intentions to protect the health and well-being of trafficking victims wish to turn their rhetoric to reality, they must put into place post-trafficking responses that have integrated health promoting strategies that meet trafficked people’s support needs.

Acknowledgements

The research was conducted as part of Siân Oram’s doctoral research, which was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, UK. The authors thank Richard Blakeley and Richard Whitaker, who assisted with the interpretation of European law. The authors would also like to thank their two anonymous peer reviewers for their insightful and constructive feedback.

Siân Oram, MA, MSc, PhD, is a Post-Doctoral Fellow in the Section for Women’s Mental Health at the Institute of Psychiatry (King’s College London), London, UK.

Cathy Zimmerman, MA, MSc, PhD, is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Global Health and Development at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK.

Brad Adams is the Asia Director of Human Rights Watch.

Joanna Busza, MSc, is a Senior Lecturer in the Department for Population Studies at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK.

Please address correspondence to the authors c/o Siân Oram: sian.oram@kcl.ac.uk.

References

1. See, for example, UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking, E/2002/68/Add.1. Available at: http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/3f1fc60f4.html. See also the Council of Europe Convention on Action Against Trafficking in Human Beings, Warsaw, 16.V.2005, available at http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/EN/Treaties/Html/197.htm and referred to hereafter as ECAT.

2. Optional Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, Supplementing the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime, G.A. Res. 55/25 (2000). Available at http://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/UNTOC/Publications/TOC%20Convention/TOCebook-e.pdf and referred to hereafter as the “Palermo Protocol.”

3. See, for example, International Labour Organization, A Global Alliance Against Forced Labour (Geneva: ILO, 2005). Available at http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_norm/@declaration/documents/publication/wcms_081882.pdf.

4. Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, G.A. Res. 39/45 (1984). Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/cat.htm; Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women, A/RES 48/104 (1993). Available at http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/48/a48r104.htm.

5. Palermo Protocol (see note 2).

6. ECAT (see note 1).

7. For studies conducted in South Asia see, for example, J.G. Silverman, M.R. Decker, J. Gupta, A. Maheshwari, V. Patel, A. Raj, “HIV prevalence and predictors among rescued sex-trafficked women and girls in Mumbai, India,” JAIDS 43/5 (2006), pp. 588-593; J.G. Silverman, M.R. Decker, J. Gupta, A. Maheshwari, B.M. Willis, A. Raj, “HIV prevalence and predictors of infection in sex-trafficked Nepalese girls and women,” JAMA 298/5 (2007), pp. 536-542; and H.L. McCauley, M.R. Decker, J.G. Silverman “Trafficking experiences and violence victimization of sex-trafficked young women in Cambodia” Int J Gyn Obstet 110 (2010): pp. 266-267. For studies of trafficking in Europe see, for example, C. Zimmerman, M. Hossain, K. Yun, V. Gajdadziev, N. Guzun, M. Tchomarova, et al., “The health of trafficked women: A survey of women entering post-trafficking services in Europe,” AJPH 98 (2008), pp.55-59; and N. Ostrovschi, M.J. Prince, C. Zimmerman, M.A. Hotineanu, L.T. Gorceag, V.I. Gorceag, et al., “Women in post-trafficking services in Moldova: Diagnostic interviews over two time periods to assess returning women’s mental health,” BMC Public Health 11 (2011), pp.232-238.

8. Zimmerman (2008, see note 7), and C. Watts and C. Zimmerman, “Violence against women: Global scope and magnitude,” Lancet 359/9313 (2002), pp.1232-1237.

9. For mental health see, for example, Ostrovschi (2011, see note 7). For sexual health, see, for example, Silverman (2006, 2007, see note 7).

10. Violence and poor health outcomes amongst trafficked men and people trafficked for labor exploitation are documented, for example, in R. Surtees, Trafficking of Men: A Trend Less Considered: The Case of Belarus and Ukraine (Geneva: International Organization for Migration, 2008) and Human Rights Center, Hidden Slaves: Forced Labour in the United States (Berkeley: University of California, 2004). For health risks and outcomes associated with child trafficking, see M. Crawford and M.R. Kaufman, “Sex trafficking in Nepal: survivor characteristics and long-term outcomes,” Violence Against Women 14 (2008), pp.905-916, and ECPAT, Cause for concern? London social services and child trafficking (London: ECPAT UK, 2004).

11. For a description of the principles of framework analysis, see J. Ritchie and L. Spencer, “Qualitative Data Analysis for Applied Policy Research,” in A. Bryman and R. Burgess (eds) Analysing Qualitative Data (London: Routledge, 1994).

12. J. Kingdon, Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies, 2nd ed (New York: Longman, 2003).

13. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI), (1966). Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/cescr.htm; the European Social Charter, 529 U.N.T.S. 89 Art 13. (1961), available at http://conventions.coe.int/treaty/en/treaties/html/035.htm; and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, 2000/C 364/01, Art 35 (2000). Available at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/charter/pdf/text_en.pdf. For the right to health, see also the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), G.A. Res. 44/25 (1989). Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/crc.htm; and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, G.A. Res. 34/180 (1979). Available at http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/text/econvention.htm.

14. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 20, Non-discrimination in economic, social and cultural rights (Article 2), UN Doc. No. E/C.12/GC/20 (2009). Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cescr/docs/E.C.12.GC.20.doc.

15. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, A/RES/34/180 (1979). Available at http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/3ae6b3970.html

16. Ibid. See also: Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), CEDAW General Recommendation No. 24, Women and Health (Article 12). A/54/38/Rev.1, chap. I (1999). Available at http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/453882a73.html.

17. Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families, G.A., Res 45/158 (1990). Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cmw/cmw.htm.

18. The UK signed the Palermo Protocol (2000, see note 2) in 2000 and ratified it in 2006. ECAT (2005, see note 1) was signed by the UK in 2007, ratified in 2008 and came into force in April 2009.

19. Palermo Protocol (2000, see note 2).

20. ECAT (2005, see note 1).

21. Residence Permit Issued to Third-Country Nationals Who are Victims of Trafficking in Human Beings or Who Have Been the Subject of an Action to Facilitate Illegal Immigration, Who Cooperate With the Competent Authorities, European Council Directive 2004/81/EC (2004). Available at http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/4156e71d4.html.

22. Preventing and Combating Trafficking in Human Beings and Protecting its Victims, EU Framework Directive 2011/36/EU (2011). Available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2011:101:0001:0011:EN:PDF.

23. Ibid.

24. Guidance on developing National Referral Mechanisms is provided by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe: OSCE, National Referral Mechanisms: Joining Efforts to Protect the Rights of Trafficked Persons: A Practical Handbook (Warsaw: OSCE, 2004).

25. USAID, Best Practices for Programming to Protect and Assist Victims of Trafficking in Europe and Eurasia: Final Report (USAID, 2008). Available at http://www.usaid.gov/locations/europe_eurasia/dem_gov/docs/protection_final_121008.pdf.

26. The NHS Charging Regulations were established by S.I. 1989/306. National Health Service (Charges to Overseas Visitors) Regulations 1989. Available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1989/306/contents/made.

27. The NHS Charging Regulations were amended by S.I .2008/2251. National Health Service (Charges to Overseas Visitors) (Amendment) Regulations 2008. Available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2008/2251/contents/made. The amendment came into force in April 2009.

28. S. Willman, Legal Rights to Welfare Provision for Trafficked Migrants, AtLEP Training Paper (London, UK: Anti-Trafficking Legal Project).

29. S.I.2008/2251 (2008, see note 27).

30. Interviewee reports were supported by analysis of meeting minutes (e.g., from the Joint NGO Ministerial Group, 2005-2010) and field notes (e.g., from meetings such as OSCE/ODIHR Round table on the UK NRM, 01/30/2009).

31. UK Home Office and Border & Immigration Agency, Impact assessment of the ratification of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (London: 2008).

32. Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (CETS No.197) Explanatory Report (2005). Available at http://conventions.coe.int/treaty/en/reports/html/197.htm.

33. Field notes from meeting of 7/31/2009 with UK Department of Health (filed with lead author).

34. The ECAT Impact Assessment provides general information on the structure of the UK NRM (2008, see note 31).

35. UK Human Trafficking Centre, NRM Statistical Data April 1, 2009 – March 31, 2011 (Sheffield: UKHTC, 2010). Available at www.ukhtc.org.

36. Ibid.

37. C. Zimmerman, M. Hossain, K. Yun, B. Roche, L. Morrison, C. Watts, Stolen smiles: The physical and psychological health consequences of women and adolescents trafficked in Europe (London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2006). Available at http://genderviolence.lshtm.ac.uk/files/Stolen-Smiles-Trafficking-and-Health-2006.pdf.

38. The Anti-Trafficking Monitoring Group, which reported on the UK’s implementation of ECAT, also notes that people who are presumed to have been trafficked but who are not assisted by NGO post-trafficking support organisations may find it challenging to access medical care. See Anti-Trafficking Monitoring Group, Wrong kind of victim? One year on: An analysis of UK measures to protect trafficked persons (London: Anti Slavery International, 2010).

39. IOM, UNGIFT, and LSHTM, Caring for Trafficked Persons: Guidance for Health Providers (Geneva: IOM, 2009). Available at http://publications.iom.int/bookstore/free/CT_Handbook.pdf.

40. Directive 2011/36/EU (2011, see note 22).

41. Ibid.

42. Ibid.

43. A. Burnett and M. Peel, “Asylum seekers and refugees in Britain,” BMJ 322/7285 (2001), pp. 544-547.

44. See, for example, C. Gorst-Unworth and E. Goldenberg, “Psychological sequelae of torture and organised violence suffered by refugees from Iraq. Trauma-related factors compared with social factors in exile,” British Journal of Psychiatry 172 (1998), pp.90-94; D. Silove, Z. Steel, P. McGorry, P. Mohan, “Trauma exposure, post-migration stressors, and symptoms of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress in Tamil asylum-seekers: Comparison with refugees and immigrants,” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 97/3 (1998), pp.175-181; and D.A. Ryan, C.A. Benson, B.A. Dooley, “Psychological distress and the asylum process: a longitudinal study of forced migrants in Ireland,” Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 196/1 (2008), pp. 37-45.

45. The UK response to human trafficking is described as “victim-centered” in a number of government documents, including, for example: UK Home Office, The government reply to the twenty-sixth report from the Joint Committee on Human Rights session 2005-06 HL Paper 245, HC 1127: Human Trafficking (London: 2006); and the ECAT Impact Assessment (2008, see note 30).